Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Villavicencio Vs Lukban

Uploaded by

charmdelmoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Villavicencio Vs Lukban

Uploaded by

charmdelmoCopyright:

Available Formats

ZACARIAS VILLAVICENCIO, ET AL., petitioners, vs. JUSTO LUKBAN, ET AL., respondents.

March 25, 1919 Facts Justo Lukban, who was then the Mayor of the City of Manila, ordered the deportation of 170 prostitutes to Davao. His reason for doing so was to preserve the morals of the people of Manila. He claimed that the prostitutes were sent to Davao, purportedly, to work for an haciendero Feliciano Ynigo. The prostitutes were confined in houses from October 16 to 18 of that year before being boarded, at the dead of night, in two boats bound for Davao. The women were under the assumption that they were being transported to another police station while Ynigo, the haciendero from Davao, had no idea that the women being sent to work for him were actually prostitutes. The families of the prostitutes came forward to file charges against Lukban, Anton Hohmann, the Chief of Police, and Francisco Sales, the Governor of Davao. They prayed for a writ of habeas corpus to be issued against the respondents to compel them to bring back the 170 women who were deported to Mindanao against their will. During the trial, it came out that, indeed, the women were deported without their consent. In effect, Lukban forcibly assigned them a new domicile. Most of all, there was no law or order authorizing Lukban's deportation of the 170 prostitutes. Issue WoN there is a law that authorizing Manila Mayors action of deporting 170 prostitutes to Davao Held There is no law. Alien prostitutes can be expelled from the Philippine Islands in conformity with an Act of congress. The Governor-General can order the eviction of undesirable aliens after a hearing from the Islands. Act No. 519 of the Philippine Commission and section 733 of the Revised Ordinances of the city of Manila provide for the conviction and punishment by a court of justice of any person who is a common prostitute. Act No. 899 authorizes the return of any citizen of the United States, who may have been convicted of vagrancy, to the homeland. New York and other States have statutes providing for the commitment to the House of Refuge of women convicted of being common prostitutes. Even when the health authorities compel vaccination, or establish a quarantine, or place a leprous person in the Culion leper colony, it is done pursuant to some law or order. But one can search in vain for any law, order, or regulation, which even hints at the right of the Mayor of the city of Manila or the chief of police of that city to force citizens of the Philippine Islands and these women

despite their being in a sense lepers of society are nevertheless not chattels but Philippine citizens protected by the same constitutional guaranties as are other citizens to change their domicile from Manila to another locality. On the contrary, Philippine penal law specifically punishes any public officer who, not being expressly authorized by law or regulation, compels any person to change his residence. RPC provides: Any public officer not thereunto authorized by law or by regulations of a general character in force in the Philippines who shall banish any person to a place more than two hundred kilometers distant from his domicile, except it be by virtue of the judgment of a court, shall be punished by a fine of not less than three hundred and twenty-five and not more than three thousand two hundred and fifty pesetas. Any public officer not thereunto expressly authorized by law or by regulation of a general character in force in the Philippines who shall compel any person to change his domicile or residence shall suffer the penalty of destierro and a fine of not less than six hundred and twenty-five and not more than six thousand two hundred and fifty pesetas. (Art. 211.) We entertain no doubt but that, if, after due investigation, the proper prosecuting officers find that any public officer has violated this provision of law, these prosecutors will institute and press a criminal prosecution just as vigorously as they have defended the same official in this action. Nevertheless, that the act may be a crime and that the persons guilty thereof can be proceeded against, is no bar to the instant proceedings. To quote the words of Judge Cooley in a case which will later be referred to "It would be a monstrous anomaly in the law if to an application by one unlawfully confined, to be restored to his liberty, it could be a sufficient answer that the confinement was a crime, and therefore might be continued indefinitely until the guilty party was tried and punished therefor by the slow process of criminal procedure." (In the matter of Jackson [1867], 15 Mich., 416, 434.) The writ of habeas corpus was devised and exists as a speedy and effectual remedy to relieve persons from unlawful restraint, and as the best and only sufficient defense of personal freedom. Any further rights of the parties are left untouched by decision on the writ, whose principal purpose is to set the individual at liberty.

You might also like

- IPL DIGESTS-NOV. 10, 2017 (1) Abs-Cbn V. GozonDocument13 pagesIPL DIGESTS-NOV. 10, 2017 (1) Abs-Cbn V. GozonTriccie MangueraNo ratings yet

- Digested - PPhil V FerrerDocument1 pageDigested - PPhil V FerrernojaywalkngNo ratings yet

- People Vs RebutadoDocument12 pagesPeople Vs RebutadoNaif OmarNo ratings yet

- Civil Law: Answers To Bar Examination QuestionsDocument119 pagesCivil Law: Answers To Bar Examination Questionsmanol_salaNo ratings yet

- Republic V MangotaraDocument11 pagesRepublic V MangotaraIvy BernardoNo ratings yet

- Secretary of National Defense V Manalo 180906Document25 pagesSecretary of National Defense V Manalo 180906MJ Magallanes100% (1)

- Mobilia Products V UmezawaDocument30 pagesMobilia Products V UmezawaRelmie TaasanNo ratings yet

- Nuez V Cruz Apao 455 Scra 228Document2 pagesNuez V Cruz Apao 455 Scra 228Earvin SunicoNo ratings yet

- People v. Del RosarioDocument9 pagesPeople v. Del RosarioMarian's PreloveNo ratings yet

- RULE 116 Cases For CrimproDocument147 pagesRULE 116 Cases For CrimproSittie Aina MunderNo ratings yet

- DigestedDocument2 pagesDigestedJoan PabloNo ratings yet

- Case Digests For Loc Gov Local TaxationDocument7 pagesCase Digests For Loc Gov Local TaxationChristelle EleazarNo ratings yet

- Valencia vs. AntiniwDocument11 pagesValencia vs. AntiniwNyok NyokerzNo ratings yet

- Abueva vs. Wood, 45 Phil 612Document13 pagesAbueva vs. Wood, 45 Phil 612fjl_302711No ratings yet

- Dunlao Vs CADocument8 pagesDunlao Vs CAEcnerolAicnelavNo ratings yet

- 0034 - People vs. Petalcorin 180 SCRA 685, December 29, 1989Document8 pages0034 - People vs. Petalcorin 180 SCRA 685, December 29, 1989Gra syaNo ratings yet

- Valmonte Vs de VillaDocument3 pagesValmonte Vs de VillaRean Raphaelle Gonzales100% (1)

- Supreme Court Ruling on Labor Case AppealDocument5 pagesSupreme Court Ruling on Labor Case AppealKep LerzNo ratings yet

- Marine Mammals Case Declares Oil Exploration in Protected Area UnconstitutionalDocument3 pagesMarine Mammals Case Declares Oil Exploration in Protected Area UnconstitutionalMark Angelo CabilloNo ratings yet

- People vs. AntiguaDocument9 pagesPeople vs. AntiguaMichael Alberto RosarioNo ratings yet

- Case Digest (Reporting) - 2Document5 pagesCase Digest (Reporting) - 2Anonymous T22QudNo ratings yet

- Gerona Vs de Guzman - G.R. No. L-19060. May 20, 1964Document3 pagesGerona Vs de Guzman - G.R. No. L-19060. May 20, 1964Ebbe DyNo ratings yet

- Jandusay vs. CA - CaseDocument10 pagesJandusay vs. CA - CaseRobeh AtudNo ratings yet

- Disini vs. Secretary of JusticeDocument29 pagesDisini vs. Secretary of Justicealoevera1994No ratings yet

- NAPOCOR Vs Spouses ChiongDocument9 pagesNAPOCOR Vs Spouses ChiongKatrina Budlong100% (1)

- Hacienda Luisita Vs PARCDocument12 pagesHacienda Luisita Vs PARCJumen TamayoNo ratings yet

- 972 Contreras Vs de LeonDocument1 page972 Contreras Vs de Leonerica pejiNo ratings yet

- Court Rules Family Home Exempt from ExecutionDocument7 pagesCourt Rules Family Home Exempt from ExecutionRubyNo ratings yet

- Marcopper Mining Corporation pollution case charges upheldDocument2 pagesMarcopper Mining Corporation pollution case charges upheldWresen AnnNo ratings yet

- Velunta v. Chief, Phil Constabulary GR No. 71855Document4 pagesVelunta v. Chief, Phil Constabulary GR No. 71855Aynex AndigNo ratings yet

- 01 Ramoso V. Ca (Agapito)Document44 pages01 Ramoso V. Ca (Agapito)Adi CruzNo ratings yet

- The Lawphil Project - Arellano Law Foundation: Silvestre L. Tagarao For Private RespondentDocument4 pagesThe Lawphil Project - Arellano Law Foundation: Silvestre L. Tagarao For Private RespondentRogelio BataclanNo ratings yet

- Dawa Vs de AsaDocument9 pagesDawa Vs de Asajcfish070% (1)

- 30 Borjal V CA 1992Document3 pages30 Borjal V CA 1992Remuel TorresNo ratings yet

- Laureano V. Adil & Ong Cu GR L-43345 - July 29, 1976 AquinoDocument2 pagesLaureano V. Adil & Ong Cu GR L-43345 - July 29, 1976 AquinoJoyelle Kristen TamayoNo ratings yet

- DOTC v. Spouses AbecinaDocument2 pagesDOTC v. Spouses AbecinaTin LicoNo ratings yet

- People v. Johnson (348 SCRA 526)Document9 pagesPeople v. Johnson (348 SCRA 526)Jomarc MalicdemNo ratings yet

- FsadasgfasDocument4 pagesFsadasgfassovxxxNo ratings yet

- Criminal Procedure Reviewer by JPCC Up To Section 8 of Rule 110Document3 pagesCriminal Procedure Reviewer by JPCC Up To Section 8 of Rule 110John CorpuzNo ratings yet

- SC Upholds Validity of Free Patent and Titles Issued to Heirs of Nicolas FelisildaDocument7 pagesSC Upholds Validity of Free Patent and Titles Issued to Heirs of Nicolas FelisildaCes Camello0% (1)

- LEGAL and JUDICIAL Ethics CasesDocument59 pagesLEGAL and JUDICIAL Ethics CasesMaylene UdtojanNo ratings yet

- Miners Association of Philippines Vs Factoran G.R. No. 98332Document9 pagesMiners Association of Philippines Vs Factoran G.R. No. 98332Christelle Ayn BaldosNo ratings yet

- Constitutionality of K12Document1 pageConstitutionality of K12AnonymousNo ratings yet

- Libit v. OlivaDocument3 pagesLibit v. OlivaKatherine EvangelistaNo ratings yet

- Cebu Portland Cement Co. v. Municipality ofDocument5 pagesCebu Portland Cement Co. v. Municipality ofDenise LabagnaoNo ratings yet

- fflmtiln: Upreme LourtDocument11 pagesfflmtiln: Upreme LourtJesryl 8point8 TeamNo ratings yet

- People vs. Tan Tiong MengDocument4 pagesPeople vs. Tan Tiong MengMj BrionesNo ratings yet

- Sandiganbayan Jurisdiction Over Estafa Case Against UP Student RegentDocument12 pagesSandiganbayan Jurisdiction Over Estafa Case Against UP Student RegentEmerson NunezNo ratings yet

- De Guzman Vs SubidoDocument6 pagesDe Guzman Vs SubidoAgz MacalaladNo ratings yet

- Ladlad vs. VelascoDocument26 pagesLadlad vs. VelascoDaley CatugdaNo ratings yet

- Spouses Belen vs. Chavez (Digest)Document2 pagesSpouses Belen vs. Chavez (Digest)RICKY D. BANGGATNo ratings yet

- People Vs MendiDocument7 pagesPeople Vs MendiVina Cagampang100% (1)

- Olbes v. BuemioDocument2 pagesOlbes v. BuemioTon RiveraNo ratings yet

- In Re Maquera (2004)Document8 pagesIn Re Maquera (2004)happymabeeNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court rules accused not entitled to bail after conviction for homicideDocument10 pagesSupreme Court rules accused not entitled to bail after conviction for homicidejomar icoNo ratings yet

- Expulsion Case No 68 Villavincencio V LukbanDocument2 pagesExpulsion Case No 68 Villavincencio V LukbanChristine ValidoNo ratings yet

- Rubi vs. Provincial Board of Mindoro FactsDocument6 pagesRubi vs. Provincial Board of Mindoro FactsnellafayericoNo ratings yet

- CRIMLAW2DIGEST1Document8 pagesCRIMLAW2DIGEST1Joey CelesparaNo ratings yet

- CasesDocument3 pagesCasesKleyr De Casa AlbeteNo ratings yet

- Human Rights Law CompilationDocument49 pagesHuman Rights Law CompilationAxel Gonzalez100% (1)

- Corpuz Vs Sto TomasDocument22 pagesCorpuz Vs Sto TomascharmdelmoNo ratings yet

- Revised Procedural Guidelines in The Conduct of Voluntary Arbitration Proceedings PDFDocument19 pagesRevised Procedural Guidelines in The Conduct of Voluntary Arbitration Proceedings PDFcharmdelmoNo ratings yet

- Reviewer For PubOffDocument8 pagesReviewer For PubOffcharmdelmoNo ratings yet

- Sta. Maria vs. SalvadorDocument22 pagesSta. Maria vs. SalvadorcharmdelmoNo ratings yet

- Revised Procedural Guidelines in The Conduct of Voluntary Arbitration Proceedings PDFDocument19 pagesRevised Procedural Guidelines in The Conduct of Voluntary Arbitration Proceedings PDFcharmdelmoNo ratings yet

- 04 Municipality of San Juan v. CADocument2 pages04 Municipality of San Juan v. CAcharmdelmoNo ratings yet

- Philippine Jurispridence 14Document8 pagesPhilippine Jurispridence 14al gulNo ratings yet

- Revised Procedural Guidelines in The Conduct of Voluntary Arbitration Proceedings PDFDocument19 pagesRevised Procedural Guidelines in The Conduct of Voluntary Arbitration Proceedings PDFcharmdelmoNo ratings yet

- Revised Procedural Guidelines in The Conduct of Voluntary Arbitration Proceedings PDFDocument19 pagesRevised Procedural Guidelines in The Conduct of Voluntary Arbitration Proceedings PDFcharmdelmoNo ratings yet

- Judicial Affidavit RuleDocument4 pagesJudicial Affidavit RuleCaroline DulayNo ratings yet

- (Digest) Dizon-Rivera V DizonDocument2 pages(Digest) Dizon-Rivera V DizoncharmdelmoNo ratings yet

- Judicial Affidavit RuleDocument4 pagesJudicial Affidavit RuleCaroline DulayNo ratings yet

- PNB v. CADocument2 pagesPNB v. CAcharmdelmoNo ratings yet

- 02 Rodelas v. AranzaDocument1 page02 Rodelas v. AranzacharmdelmoNo ratings yet

- Probate of Holographic Will Upheld Despite Unsigned AlterationsDocument2 pagesProbate of Holographic Will Upheld Despite Unsigned AlterationscharmdelmoNo ratings yet

- Sison v. DavidDocument3 pagesSison v. Davidcharmdelmo100% (1)

- Acuña V VelosoDocument2 pagesAcuña V VelosocharmdelmoNo ratings yet

- PNB Vs QuimpoDocument2 pagesPNB Vs Quimpocharmdelmo100% (1)

- Sison v. DavidDocument3 pagesSison v. Davidcharmdelmo100% (1)

- PNB Vs QuimpoDocument2 pagesPNB Vs Quimpocharmdelmo100% (1)

- CAUSES OF ACTION DISMISSEDDocument2 pagesCAUSES OF ACTION DISMISSEDcharmdelmoNo ratings yet

- Dorotheo v. CADocument2 pagesDorotheo v. CAcharmdelmo100% (2)

- Lawyers Coop v. TaboraDocument4 pagesLawyers Coop v. TaboracharmdelmoNo ratings yet

- Dorotheo v. CADocument2 pagesDorotheo v. CAcharmdelmo100% (2)

- Blake V WeidenDocument2 pagesBlake V WeidencharmdelmoNo ratings yet

- Luzon Brokerage Vs Maritime BLDGDocument8 pagesLuzon Brokerage Vs Maritime BLDGcharmdelmoNo ratings yet

- Blake V WeidenDocument2 pagesBlake V WeidencharmdelmoNo ratings yet

- Qua Chee Gan v. Law UnionDocument9 pagesQua Chee Gan v. Law UnioncharmdelmoNo ratings yet

- Gercio vs. Sun LifeDocument7 pagesGercio vs. Sun LifecharmdelmoNo ratings yet

- APT liable for damages due to failure to deliver machineryDocument12 pagesAPT liable for damages due to failure to deliver machinerycharmdelmoNo ratings yet

- Construct Basic Sentence in TagalogDocument7 pagesConstruct Basic Sentence in TagalogXamm4275 SamNo ratings yet

- 2016-2017 Course CatalogDocument128 pages2016-2017 Course CatalogFernando Igor AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Murder in Baldurs Gate Events SupplementDocument8 pagesMurder in Baldurs Gate Events SupplementDavid L Kriegel100% (3)

- ACC WagesDocument4 pagesACC WagesAshish NandaNo ratings yet

- Overtime Request Form 加班申请表: Last Name First NameDocument7 pagesOvertime Request Form 加班申请表: Last Name First NameOlan PrinceNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For ValuationDocument6 pagesGuidelines For ValuationparikhkashishNo ratings yet

- Fil 01 Modyul 7Document30 pagesFil 01 Modyul 7Jamie ann duquezNo ratings yet

- Class Xi BST Chapter 6. Social Resoposibility (Competency - Based Test Items) Marks WiseDocument17 pagesClass Xi BST Chapter 6. Social Resoposibility (Competency - Based Test Items) Marks WiseNidhi ShahNo ratings yet

- Quicho - Civil Procedure DoctrinesDocument73 pagesQuicho - Civil Procedure DoctrinesDeanne ViNo ratings yet

- Wonka ScriptDocument9 pagesWonka ScriptCarlos Henrique Pinheiro33% (3)

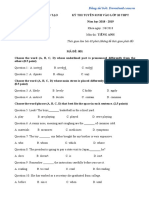

- Đề thi tuyển sinh vào lớp 10 năm 2018 - 2019 môn Tiếng Anh - Sở GD&ĐT An GiangDocument5 pagesĐề thi tuyển sinh vào lớp 10 năm 2018 - 2019 môn Tiếng Anh - Sở GD&ĐT An GiangHaiNo ratings yet

- Neat Veg Report Final PDFDocument50 pagesNeat Veg Report Final PDFshishirhomeNo ratings yet

- Special Educational Needs, Inclusion and DiversityDocument665 pagesSpecial Educational Needs, Inclusion and DiversityAndrej Hodonj100% (1)

- Vivarium - Vol 37, Nos. 1-2, 1999Document306 pagesVivarium - Vol 37, Nos. 1-2, 1999Manticora VenerabilisNo ratings yet

- Pharma: Conclave 2018Document4 pagesPharma: Conclave 2018Abhinav SahaniNo ratings yet

- Narrative On Parents OrientationDocument2 pagesNarrative On Parents Orientationydieh donaNo ratings yet

- Maxwell McCombs BioDocument3 pagesMaxwell McCombs BioCameron KauderNo ratings yet

- Week 1 and 2 Literature LessonsDocument8 pagesWeek 1 and 2 Literature LessonsSalve Maria CardenasNo ratings yet

- Everything You Need to Know About DiamondsDocument194 pagesEverything You Need to Know About Diamondsmassimo100% (1)

- Hold On To HopeDocument2 pagesHold On To HopeGregory J PagliniNo ratings yet

- Influencing Decisions: Analyzing Persuasion TacticsDocument10 pagesInfluencing Decisions: Analyzing Persuasion TacticsCarl Mariel BurdeosNo ratings yet

- Understanding Culture, Society and PoliticsDocument3 pagesUnderstanding Culture, Society and PoliticsแซคNo ratings yet

- High-Performance Work Practices: Labor UnionDocument2 pagesHigh-Performance Work Practices: Labor UnionGabriella LomanorekNo ratings yet

- Effecting Organizational Change PresentationDocument23 pagesEffecting Organizational Change PresentationSvitlanaNo ratings yet

- Ford Investigative Judgment Free EbookDocument73 pagesFord Investigative Judgment Free EbookMICHAEL FAJARDO VARAS100% (1)

- Aikido NJKS PDFDocument105 pagesAikido NJKS PDFdimitaring100% (5)

- MGT420Document3 pagesMGT420Ummu Sarafilza ZamriNo ratings yet

- VI Sem. BBA - HRM Specialisation - Human Resource Planning and Development PDFDocument39 pagesVI Sem. BBA - HRM Specialisation - Human Resource Planning and Development PDFlintameyla50% (2)

- Esp 7 Q4M18Document13 pagesEsp 7 Q4M18Ellecarg Cenaon CruzNo ratings yet

- Marine Insurance Final ITL & PSMDocument31 pagesMarine Insurance Final ITL & PSMaeeeNo ratings yet