Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Nuenning On-Metanarrative PDF

Uploaded by

kbantleonOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Nuenning On-Metanarrative PDF

Uploaded by

kbantleonCopyright:

Available Formats

Narratologia

Contributions to Narrative Theory/

Beitrage zur Erzahltheorie

Edited by/Herausgegeben von

Fotis J annidis, John Pier, Wolf Schmid

Editorial Board/Wissenschaftlicher Beirat

Catherine Emmott, Monika Fludernik

Jose Agel Garcia Landa, Peter H iihn, Manfed Jahn

Andreas Kablitz, Uri Margolin, Matias Martinez

Jan Christoph Meister, Ansgar Niinning

Marie-Laure Ryan, Jean-Marie Schaeffer

Michael Scheffel, Sabine Schlickers, J org Schonert

4

Walter de Gruyter Berlin New York

Te Dynamics

of Narrative For

Studies in Anglo-Aerican Narratology

Edited by

John Pier

Walter de Gruyter Berlin New York

@ t..-...-.......,.,..-........-....-...,.....-..

.....s....-....,..-.-.-...-...- ....,

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

d. Anglo merican

The dynamic of narrative f . U ies -

narratology edited by John

_

Pier.

p. cm - ( arratologia 4)

.

Includes bibliographical reference and mdex

ISB J-1!-\6J14J alk. paper)

.

l arration (Rhetoric) - Congresses. I. Pier. Jlm

Hoimes. 1. European Society for the tudy of English.

i:is.....

t:::u-s :

~.::

ISBN 3-11-018314-5

ISSN 1612-8427

:::-

Bibliographic information published by Die Deutsche Bibliothek

u..u.......a.-................,.

-

-

..

.....

.

- _

.

.

...

.

__.

......--.,..,............. ..

c - c xcu:a....-

c.,,..,..:- , w......c..,... - .

.

.

languaoes part of !h:s

All rights reserved. includng ...

.......

.

_

onic or .. includ

book may breprodu

d -.-,..-.

. ,

. -......and retrieval ystem ' ithou.

ino photocopy. recording, -..-,H ..-.1\

.

,......-.--..,a.-...,.- ......

c.......,-c......,...s..-....a....-

t..-...-c..-.-,

Prefce

The contributions to the present volume all reflect, in diferent ways,

some of the directions taken by narratology since the early 1990s

under the banner of what has come to be called in many quarters

"post-classical" narratology. As the readers of a volume such as this

are likely to be aware, developments in narrative theory in recent years

do not necessarily mark a clean and revolutionary break with the

earlier "classical" narratology, fr the crisis to which the original

paradigms, models and methodologies led-quite diverse in them

selves-has proved to be less an impasse than to have given rise to a

new impulse in the principled study of narrative so innovatively exem

plifed by the initial narratological studies.

The majority of these contributions originated during the

Narratology Panel at the sixth congress of the European Society fr the

Study of English held in Strasburg in September 20021 No precise

topic or methodological approach was set, but participants (and

subsequently the other contributors) were invited to engage in stock

taking on themes of their own choice, charing out vistas of potential

interest for the fture of narratologically-inspired research. Given the

diversity of topics and, in some cases, the divergent theoretical premises

adopted by the contributors, no claim can be made to a unifed body

of research or to a fndamental postulate shared by all.

This is as it should be.

Readers of the fllowing pages will not fil to notice the rigor and

coherence running through each of the essays in their own right, and

on this basis alone any attempt to seek out a centralizing doctrine

would be largely fitless, and unfortunate. Various groupings and

cross-groupings will nonetheless crop up, not so much as a matter of

common presuppositions or concurent conclusions as that of a

stimulating contrast of views on similar or related narratological topics.

Most striking in this regard is Rene Rivara's critique of fcalization as

inherited fom Gerard Genette and his successors and the post

structuralist refrmulation of fcalization proposed by Luc Herman

and Bart Vervaeck. The frmer, based on French enunciative linguistics

and the insistence of reuniting "Who sees?" with "Who speaks?", is a

Papers Oy Jose

A

ngel Garcia Landa, Peter Hihn, Dieter Mei ndl, -.,...--.-,

s.--Pier and Michael Toolan.

6 Prefce

systematic exploration of the viewpoints available to narrative fiction,

while the latter investigates how fcalization is woven into other

fatures of narative such as plot, theme and metaphorical and

metonymic devices: one employs sophisticated analytical tools to refne

a concept as it was synthesized in "classical" narratology; the other is

a "post-classical" expansion of that concept aimed at exploring new

dimensions of established narratological categories.

In diferent ways and to various degrees, this patter corresponds to

the tendencies illustrated by many of the other contributions. This is

not to say, however, that each article is to be paired with another or that

the order in which the aricles appear precludes groupings that may

highlight other problems of interest fr narrative study. Again, each

contribution stads on its own, ad while Michael Toolan's "Graded

Expectations" and Joh Pier's "Narrative Confgurations," fr in

stance, both bear in pa on the sequential ordering of narrative texts,

this is neither fr the same reasons nor with the same consequences,

even though each approach may possibly shed light on the other. Jose

Angel Garcia Landa draws attention to the rarely studied question of

how narrative tends to be "overheard," with the intrusion of a

parasitical "unaddressed" reader into the universe of discourse

upsetting the neat ft so readily assumed to exist between narratological

schemes and communicative processes. The twists and turs thus

caused in the fnctioning of narrative communication may open the

way to frher analysis on the basis of Dieter Meindl's 'pronominal"

theory of reliable and unreliable narration. In yet another deparure

fom earlier tenets, there is a growing awareness that narative fatures

are not restricted to discourses (verbal or other) dominated by the

telling of stories. Thus, Peter Hihn, in fcusing on the implementation

of narrative sequentiality and mediacy through an act of articulation as

this occurs in lyric poetry-a frm of discourse not generally

characterized by the present recounting of past happenings or by the

prominence of fcalization associated with prose fction, fr ex

ample-puts frth a compelling argument fr the insights to be gained

fom "transgeneric" applications of narratology. Wit regard to story,

moreover, one of the practices of the strcturalist narratologies, now

contested, is the story-oriented analysis of plot. Hilary P. Dannenberg

approaches this problem through possible worlds theory, showing how,

in the "temporal orchestration" of alterative possible worL' t also

of counterfctual worlds ad transworld identity, plot emerges as

Prefce 7

ontological layering, rather than as mere anachronic or proleptic

inversions of a unilinear and chronological "actual world" story by

discourse. And fnally, while all the articles in this collection tend to

reposition issues frmulated by earlier narrative theories in light of the

broad spectrum of recent developments, Ansgar Niinning's con

tribution on metanarrative, studied only sporadically by both the

"classical" and the "post-classical" narratologies, is exemplary in

clarifing a heretofre confsed concept, providing it with a theoretical

fundation, a detailed typology with numerous examples and sug

gestions fr frther study.

These questions and their possible convergences are but a sampling

of the paths of inquiry that readers might be tempted to fllow up.

Indeed, the topics debated in the fllowing pages have all been

examined more or less extensively in earlier studies. It is, however, in

redefning and in reorienting concepts and methods in light of past and

recent evolutions that the contributors to this volume have sought to

capture the dynamic processes of narrative and of narratological

research.

On behalf of all contributors, I wish to tha Michail Tavonius and

Karin Pafort fr their superb devotion and expertise in preparing the

layout of this yolume.

John Pier

ANSGAR NNING

On Metanarative:

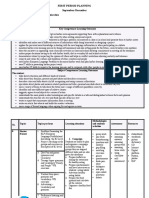

Contents

Towards a Defnition, a Typology and an Outline of the

Functions ofMetanarative Commentary. .. ..... .. ............ . . .. . .. ... .. . . . .. . . . 1 1

DIETER MEINDL

(Un-)Reliable Narration fom a Pronominal Perspective . .......... .. ... .. 59

RENE RVARA

A Plea fr a Narator-Centered Narratology. ....... . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .... 83

Luc HERMAN, BART VERVAECK

Focalization between Classical and Postclassical Narratology . . . . . . . . . 1 1 5

PETER HUHN

Transgeneric Narratology: Applications to Lyric Poetry........ . . . . . . ..... 1 39

HILARYP. DANNENBERG

Ontological Plotting:

Narrative as a Multiplicity of Temporal Dimensions.............. .......... 1 59

JOSE ANGEL GARciA LANDA

Overhearing Narrative. . . . . . . . . . . . ... . . . . . . . . . . . . . ....... . ... . . . . . . . . . ........ .. . . .. . . .... . . . . . 1 91

MICHAEL TOOLAN

Graded Expectations:

On the Textual and Structural

Shaping of Readers' Narative Experience ......e .........=...... . . . . ... . . ....... 21 5

JOHN PIER

Narrative Confgurations ......==.. . . . . + . . . . . . ........ .=. ... . . . . . . . ....... . . . . . . ....... . . . . . . 239

NAME IDEX........................................................................................ 269

ANSGAR NUNNIG

(GieBen)

On Metanarative:

Towards a Defition, a Tyolog and an Outline of the

Functions of Metanarative Comentary

While the importance of the concept of metafction has long been widely

recognized, the diference between metafction and metanarrative has

generally been overlooked. This paper argues that one needs to distinguish

between metafction and the phenomenon of metanarration. It addresses

some of the terminological and typological issues pertaining to the con

cept of metanarration, providing a defnition and a typology of meta

narative comments as we1l as d outline of the fnctions they can flfl in

fctional naratives. The frst two parts of the paper are devoted to the

intoduction and defnition of the notion of metaarrative and to the dis

cussion of some of the problems surounding it. Section three develops a

set of categories fr the analysis of and typological distinction between

diferent kinds of metanarrative commentary. The fu section provides

a brief historical overview of the fnctions that metanarrative comments

have flflled in British novels fom the end of the seventeenth century to

the present. The fnal section gives a bref summary and suggests that

much more work needs to be done1

I wanted this whole thing to be poetic. It started out poetic. Now it's just me, yaketty

ya.

I'll let you into a secret: I spent half a night-fight on the frst three paas. I think I

might have mentioned this already. I didn't read Nora fr more than about ten

would like |o thank Monika Fludemik (Freiburg), Peter Hihn (Hamburg) Jorg

Schonert (Hamburg) and other members of the Hamburg research group on

'Naratology," well Werer Wolf (Gra) and my wife Vera fr various important

ideas, textual examples, and critical comments (e.g. on the defnition of metanaration

and metafction) on earlier papers covering roughly the same material (cf A. inning

[200Ja], [2001b]). am particularly gratefl to my assistants Gaby Allrath, Dorothee

Birke and Ros Lawson fr their splendid help with the English version of this paper.

12 Ansgar Ninning

minutes. Mailer, not blahdy Barry. I spent four and a half hours composing the star.

(Ada Thorpe, Still [1995])

2

1 . Introduction: Metanarration as a gap in literary terminology

Metanarration, i.e. the narrator's commenting on the process of narration,

has been one of the constitutive elements of the 'rhetoric of fction' (sensu

W.C. Booth) since the beginnings of the novel. Moreover, self-refexive

refrences are an integral component of everyday narration, anecdote,

ballad and urban legend. In many literary narative texts, both frst-person

and authorial narators fequently address a fctitious interlocutor and talk

about their own narrative. Some quotations fom well-known works of

English narrative literature since the Middle Ages can serve as a frst

indication of how widespread the phenomenon of metanarration actually

1s:

Er that I ferher in tis tale pace,

Me thynketh it acordaunt to resoun

To telle yow al the condicioun

Of ech of hem, so as it semed me,

And whiche they weren, and of what degree,

And eek in what ar ay that tey were inne;

And at a knyght than wol I frst bigynne.

(Geofey Chaucer, "General Prologue", The Canterbur Tales [ea. 1380-1400])3

Now the reader I suppose to be upon thors at tis and the like imperinent digressions,

but let him alone and he'll come to himself; at which time I think ft to acquaint him,

that when I digress, I am at that time writing to please my self; when I continue the

thread of the stor, I write to please him; supposing him a reaonable ma, I conclude

him satisfed to allow me this libery, ad so I proceed. (William Congreve, Incognita

or, Love and Dut Reconcil'd. A Novel [1692])

4

Now it is our Purose in the ensuing Pages, to pursue a contrary Method. When any

extraordinary scene presents itself (as we trust will ofen be the Case) we shall spae no

Pains nor Paper to open it at large to our Reader; but if whole Years should pass

without producing any thing worhy his Notice, we shall not be afaid of a Chasm in

our Histor; but shall hasten on to Matters of Consequence, and leave such Periods of

Time totally unobserved. (Henr Fielding, The History of Tom Jones: A Foundling

[1749])

5

Thore (1998: 34 ).

Chaucer(1957: 17).

4

Congreve ( 1930: 250).

Fielding (1975: 76).

On Metanaative 13

Wheter I shall D out to be the hero of my own lif, or whether that station will be

held by anybody else, these pages must show. To begin my life with the beginning of

my lif, I record that I was bor (as I have been infred and believe) on a Friday, at

twelve o'clock at night. (Chales Dickens, The Personal History ofDavid Coppeield

[ 1849/50])

6

If you really want to hear about it, the frst thing you'll probably want to know is

where I was bor, and what my lousy childhood was like [ ... ] and all that David

Copperfeld kind of crap, but I don't fel like going into it. (J.D. Salinger, The Catcher

in the Rye [1951])

7

!you're late and you missed the beginning then fankly you won't understand a single

thing fr the next twelve hours, you might as well go lea some maners someplace

else. (Adam Thorpe h( 1995)

8

I have a discovery to repor. [ ... ] Now, where do I start? (Michael Frayn, Headlong

[1999])

9

Given the fct that one could produce an endless list of metanarrative

comments, it is striking tat naative theory has accorded only very little

attention to such genuinely narratological phenomena as narratorial

digressions and metanarrative interventions, despite their ubiquity in

narrative literature: in spite of its indulgence in theory and terminology,

narratology, with only one single exceptionio, has hardly devoted any

attention to metanarrative comments. Neither in recent overviews or

introductions to narrative theory11 nor in specialist studies like Monika

Fludemik's Towards a 'Natural' Narratolog (1 996), Andrew Gibson' s

Towards a Postmoder Theor ofNarrative ( 1 996) or Michael Keams' s

Rhetorical Narratolog (1 999) has the phenomenon of metanarration

played aything more than a subordinate role12

6

Dickens (1966: 49).

7

Salinger ( 1958: 5).

8

Thorpe (1998: I].

9

Frayn (1999: I).

lO

1

1

2

Cf. Prince (1982: 115-128), who has devoted one subchapter to te phenomenon of

metanarrative called "Meta.narrative Signs." All other intoductions to narrative theor

include only ver fw remarks wthout, however defning metanarative comments or

offering typological difrentiations, naratological characterizations or fctional dis

tinctions. Some prelimina thoughts on this topic ca be fund in A. Ninning (200la),

(2001b).

See, e.g. the very good intoduction by MatinezSchefel (1999), who at least discuss

these problems in a short subchapter on the "Subjekt und Adressat des Erzilens (Wer

erihlt wem?)" (ibid.: 84-89).

Several seminal collections of essays likewise ignore this topic; see, e.g., Herman

(1999) and Grinzweig/Solbach (1999). Cf., however, a recent paper by Fludernik

14 Ansgar Ninning

The underlying thesis of this essay-that the phenomenon of meta

narration has thus fr been a lacuna in narrative theory-is actually con

frmed by the fw studies that are devoted to this topic or that just mention

it in passing: they neither attempt to defne the phenomenon of meta

narration or to diferentiate between the diferent types, nor do they con

sider which fnctions such expressions could flfl in individual cases13

There is also a lack of studies examining te use of metanarrative frms in

the works of individual autors or in given periods of literay history.

This rough sketch of the neglect metanarration has sufered is the

starting point of this essay, which will tr to bridge the gap by staking out

three aims: frst of all, the terms 'metanarration' or 'metanarrative com

ments of the narrator', which have only been used sporadically in nar

rative theory so far, will be defned. Next, some steps towards a typology

and a poetics of metanarration will be presented (section 3) which can

then serve as a basis fr a survey of the changing fnctions of meta

narrative expressions in English novels fom the seventeenth to the late

twentieth century (section 4). A short summary and a brief look at some of

the points that fture research might explore will complete this article

(section 5).

2. On te defnition of 'metanarration' or 'metanarrative comments'

Although the terms 'metanarration' or 'metanarrative comments' have

been used in some narratological studies14, they have not become common

or widespread categories of narrative theory or literary studies, let alone

household words of narratology15. There ae aguably two reasons fr this:

(2003), which is partly a rejoinder to my earlier aricles on the topic (see A. Ninning

(200l a], [200lb]) ad which elaborates on several of te topics addressed in this essay.

13 The only exception to this is the subchapter by Prince ( 1 982: 1 1 5-1 28) mentioned

above, who also refects on the fnctions of metaar ative pasages.

14 Cf, e.g. Genette (1 980: 228, 255), Hamon ( 1 977), Bonheim ( 1 982: 1 3), Prince (1 982:

l 1 5f.), Prince ( 1 987: 5 1), A. Niinning (1 989: 1 2{1 21 , 1 47-148, 1 56-1 57, 1 6{-1 61 ,

1 65-166, 250-251 , 308), Fludemik (1993: 443), Madsen/Madsen ( 1 995), A. Ninning

( 1 997: 340-341 ), Schefel (1 997: 46f), Cutter (1 998), and A. Niinning (2000),

(2001 a).

15 Bonheim (1 982: 13) ofers a brief defnition of the ter 'metanar ative'; cf. also Prince

( 1982: 1 1 5-1 28). On the wide variety of seemingly related terms fr various frms of

self-refexive naratives ad metafctional techniques, cf. Schefel ( 1 997: 46-7).

Fludemik (2003) discusses the diferences between the English and Gera usages of

the terms 'metaarative' ad 'metafctional' ad teir derivatives in detail.

On Metanarative 15

frstly, the term 'metafction' is so widely used in English that frms of

metanarration tend to be subsumed under this umbrella, and while 'meta

narrative' is common as an adjective, the appropriate noun traditionally

used is 'metafction' and not 'metaarrative' or 'metanaration'. Secondly,

in the fw contributions in which the term 'metanarrative' is used at all, it

is generally perceived as an English equivalent of 'grand recit' (sensu

d . h' t"

,

1

6

Lyotard) an thus as synonymous wit master narra 1ve .

The rather shabby and contradictory treatment of diferent frms of

metanarratives is indicated by the fct that in the English translation of

Genette's "Discours du recit" (1972), Narrative Discourse (1980), the

term 'metanarrative' appears in two quite diferent senses: On the one

hand, it refrs to the phenomenon of narative embedding and to nar

ratives on a hierarchically lower level: "[T]he metanarrative is a na ative

within the narrative"17. On the oter hand, Genette and his translator both

use the term as an unspecifc umbrella ter to thematize te 'interal or

ganization' of the text, i.e. fr diferent frms of self-refexive narration.

Whereas fr Genette, 'narative fnction' refrs to the story, metanarrative

expressions rather take the text itself as teir refrence point: "The second

aspect is the narrative text, which the narrator can refr to in a discourse

that is to some extent metalinguistic (metanarrative, in this case) to mark

its articulations, connections, interrelationships, in short, its interal orga

nisation"1

8

. Genette thus explicitly limits the term 'metanarrative' to the

narrator's "directing fnctions" (onctions de regie)19, although the spec

trum of metanarative expressions is much broader in practice.

1

6

The MLA bibliography ofers about 30 entries on the ter 'metanarative', almost all

of which, however, are not related to nar atology in a strict sense. As representative of

various other essays that use 'metanarative' as an equivalent of grand recit and

synonymous with 'master narrative', cf. Hutcheon (1 989/1 996), who is only concered

with the "incredulity towad metaaratives" typical of postmodemism and who uses

the ter synonymously with "grnd totalizing mater narative" (ibid.: 262).

17 Genette (1 980: 228 n. 41 ). In the French orginal, however, Genette ( 1 972: 239 n. l )

uses the term 'metarecit': "le metaecit est un recit das le recit".

18 Genette (1 980: 255). "Le second [aspect du recit] est le tete narrative, auquel le

narrateur peut se referer dans un discours en quelque sorte metalinguistique

(metanaratif en !' occurrence) pour en maquer Jes articulations, Jes connexions, Jes

interrelations, brefl 'orgaisation inteme" (Genette [ 1 972: 261-262]).

19

Genette (1 980: 255).

1 6

Ansga Ninning

In most cases, moreover, no clear distinction is made between meta

narration and metafction20, although these are in fct two very diferent

phenomena: the frst concers the narator's refections on the discourse

or the process of narration, the second refrs to comments on the fction

ality of the narrated text or of the narrator. Metanaration and metafction

have one point in common-namely, that they are both related to frms of

literary self-refrentiality; however, these two types of narrative self

refexivity difer considerably, and this point has tended to be overlooked

in all typologies so far21

Therefre, te widely used umbrella term 'metafction' not only needs

to be elaborated22, but a clear distinction also has to be made between

metanarration and other frms of self-refexive narration. Following

Wolfs defnition of metafction as a frm of discourse which makes the

recipient aware of the fctionality (in the sense of imaginary refrence

and/or constructedness) of the narative23, it becomes clear that the term

cannot be put on a par with 'metanarration'. The latter refrs more to

those frms of self-refexive narration in which aspects of narration (and

not the fctionality of the narated) become te subject of the narratorial

discourse. Moreover, whereas metafction can by defnition only appear in

the context of fction, types of metanarration can also be fund in many

non-fctional narative genres and media. Metanaative interventions may

result in a destuction of aesthetic illusion, if tey disclose the fctionality

of the characters at te same time; this, however, does not alter the basic

theoretical diference beteen metanarration and metafction.

2 Cf, e.g. the fllowing defnition of 'metafction', which is very misleading because it

actually describes the ter 'metanaration': "Metafktion liegt immer dann vor, wenn

das Erzihlen zum Gegenstand des Erzihlens wird und damit seinen unbewuBten oder

'selbstverstidlichen' Chaakter einbiBt" (Lofer et al. [1974/2001: l 13]). Elsewhere

in the sae introduction, te authors refr to "moder anmutenden Techniken von

Selbstrefexivitit und Metaaration" (ibid.: 153), however, without defning the term

'Metanaration'.

2!

The most comprehensive typology of literary self-refexivity to date can be fund in

Wolf (2001). Even though metanarrative is alluded to several times (cf. ibid.: 56,

70-71 ), it is not discussed a a category in its own right.

~~

On a more detailed subdifferentiation, cf. Wolf (1993), (2001) as well as Scheffel

(1997: 48): "[l]nsofr ist der Begrif der narativen Selbstrefexion schon a priori von

dem der 'Metafktion' zu unterscheiden." Schefel is right when he argues that

metanarative comments do not have to underine the 'fction of a fctual naration'

(ibid.: 58).

23 Cf. Wolf(l993), (2001).

On Metana ative 1 7

Naratological research has so far fcused on self-conscious fction and

self-conscious narrators24, concentrating on metafctional frms of narra

tive self-refexivity or self-refrentiality. In contrast, metanarative

comments which do not destoy the illusion of a narated world have hard

ly received any attention25 In principle, one may assume that metanar

ration, depending on the type and context, can just as well support the

illusion of authenticity created in a text and in the act of narration. The

novels written by Aphra Behn ad Daniel Defe, fr instace, well as

quite a number of 'postmoder' novels-fom William Boyd's Te New

Confessions (1987) to Kazuo lsbiguro's When We Were Orphans

(2000}-can testify to this. It is precisely the concept of narratorial i11u

sionism i.e. narrations evoking the illusion of a personifed voice, sug

gesting the presence of a speaker or narator which I have explicated and

defned elsewhere26, that renders obvious that metanaative expressions

do not have to disturb the aesthetic illusion; rather, they can serve to

create a diferent type of illusion by accentuating the act of narration, thus

triggering a diferent strategy of natralization, viz. what Fluder has

flicitously called "the fame of storytelling"27

In contrast to the widespread mingling of metanarration and metafc

tion, then, one must be aware that metanarrative comments are a distinct

frm of narratorial utterances displaying a variety of textual fnctions.

This is also indicated by the entry in the one single specialist encyclo

paedia of narratology, in which the term 'metanarrative is defned as

fllows:

metanarrative. About narrative; describing nar ve. A narrative having (a) narative

(one of its topic(s) is (a) metanarative. More spcifcally, a narative refrring to

itself and to those elements by which it is constituted and communfoated, a nar ative

discussing itself, a self-refexive narve, is metanarative

28

Those commentaries and refections which explicitly address aspects of

naration in a self-refexive manner can thus be subsumed under the term

2

4

Cf. Booth ( 1952).

~

This diferentiation is also at least implicitly made by Chatman (1978: 248): "A basic

dichotomy has suggested itself between discourse comments that do or do not undercut

the fbric of the fiction. The frer have come to be called 'self-conscious' naation."

On self-conscious fction, cf, e.g. Alter (1975), Hutcheon (1984), Waugh (1984), and

Wolf(1993).

26 LNinning (2000), (2002).

27 tlu0cIk( 1996: 341 ).

2

8

Prince (1987: 51).

18

Ansgar Ntnning

'metana ative expressions'29 Although such comments are detached fm

the narated world, they still do not possess a high degree of generality

since they refr to one specifc object Le. the act of narrating. In

metanarrative expressions, a narrator can discuss questions of literary pro

duction or aesthetic problems, or s/e can even fregound the process of

na ation itself Metanarative fnctions are dominant in those expressions

of a narrator in which attention is drawn to the narrative fnctions3

0

I

thus becomes clear that the phenomenon of metanarration cannot be re

stricted to the narrator' s 'directing fnction' , and that it has to be dis

tinguished fom metafction.

Directing fnctions, fashfrwards and fashbacks, as well as other

metanarative utterances of the narrator do not just lead to a higher degee

of self-refexivity; they also freground the act of narrating. Since such

self-refexive comments can be defned according to their refrence to the

act of naration, they make the reader realize that what s/he is dealing wit

is a narrative. It is precisely an accumulation of such metaarative ex

pressions, which Fludemik calls "a deliberate metaarrative celebration of

the act of narration," that helps to create the illusion of a 'teller' , a

personalized voice serving as a narrator: "This reading strategy may be

actively encouraged by the text if the self-refexive or metanarrative mode

. . f f th 1""

1s a promment eature o at nove .

In contrast to Genette s limiting of the term 'metanarrative' to nar-

ratorial ' directing fnctions', one can assume that all comments refrring

to the narrative process or to one of its aspects will have a metanarrative

character. Not only statements refrring to the process of narrating are

metaarative, but the narator's refrences to his or her communication

with the narratee on te discourse level also have metanarrative character:

"The overt narrator [ . . ] can comment both on the content of the narration

(story world) and on the narrating fction itself; the address to a narratee

~

According to his basic differentiation between story und discourse, Chatman ( 1 978:

248f) refers to such metanarative comments of the narator as "commentary on the

discourse": "'Self-conscious' naration is a ter recently coined to describe comments

on the discouse rather than the story" (ibid.: 228). For a more precise defnition, see

Prince (1982: 1 5f).

`" For a similar defnition, cf. Bonheim ( 1982: 1 3): "For works of literature contain some

elements outside the space/time continuum of the fctional world, including titles,

mottoes, prefces, postscripts, refections of the author or narator concering his

literary endeavours, and addresses to the reader. I shall call such elements

metanarrative."

31 Fludemik (1 996: 275, 278).

On Metaarative 19

is part of this metanarrative perfrmance"32 All narratorial fnctions

relating to the mediation, i.e. comments which refr primarily to the act of

narration or the communication situation on the discourse level, are

therefre 'metanarative' in a wider sense.

On the basis of these definitions, it seems reasonable to argue that not

all frms of self-refexive narration should be called 'metanarrative'33 A

procedure like mise en abyme, fr example, is self-refexive, but not meta

narrative. The same holds true fr all those forms of literary self

refexivity which Schefel subsumes under the term 'mirroring'34 Rather,

the term 'metanarration' or 'metanarrative' is only appropriate when the

act of narrati ng or fctors of the process of narration are discussed.

Comments with dominantly metanarrative fnctions are thus to be dis

tinguished fom metalinguistic comments35, in which attention is fcussed

on the language itself or on the polysemy of words36 Unlike meta

linguistic comments, metanarrative statements are characterized by the

fct that the narrator refects on the process of narration. I contrast to the

widespread equation of metanarration with metafction or metalinguistic

comments, Lanser uses the category "narrative selconsciousness" in the

sense of narrative self-refexivity or metanarration: "We can posit a suc

ceeding continuum of diminishing self-consciousness of the narrative

t"3

7

A d' h d

ac . ccor mg to t e mo el she puts frward, diferent levels of inten-

sity of narrative self-refexivity can be graded on a scale in which the

poles represent a well-defned level of "narrative self-consciousness" and

"narrative unconsciousness" (which she defnes as "narrators who show

3

2

Fludemik (1 993: 443).

`` Cf. also Hempfr (1 982: 1 36), who explicitly limits the ter 'autoreflexivity' to

immediate self-refexivity concerning comments on the 'narrative discourse'. On a

diferentiation between metanarative utterances and other frs of self-refective

nar ative, cf. also Prince (1 982: 1 1 7-1 1 8), Schefel (1 997), and the section on "Models

of Meta-ization" in Fluderik (2003). The most comprehensive and detailed discussion

34

of frs of litera self-reflexivit can be fund in Wolf (1 993), (2001 ).

Scheffel ( 1 997: 54f).

35 Cf. Roman Jakobson's ( 1 960) model of verbal communication, in which he

distinguishes six fnctions of laguage, among them the metalinguistic fnction. For a

systematic attempt to integrate Jakobson' s model with the various fnctions of the

narator, including metanarative utteraces, cf Ninning ( 1 989: 1 24), ( 1 997: 339f,

esp. te model on page 342).

Metalinguistic commentary can have an implicitly metanarrative character, but the

diferentiation between metalinguistic and metanarative comments is not suficiently

3

7

obvious in Prince ( 1 982: 1 21 ).

Lanser (1 981 : 1 76, 1 77).

20

Ansga Ninning

. .

,,3g)

not the slightest awareness of a narratee or a commumcat1ve context ,

respectively.

"

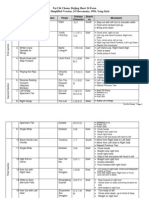

"

o

"

=

C ..

O

o

"

"

"

c

E

"

K

o

C '-

" o 'C

f

"

+ 0

W

f = &

=

o

.,

f

"

=

"

c

o

.;

"

"

o C

"

o =

F

~

.

C

"

o C "

~

o

Y

c

~ "

c

&

=

"

.,

=

c =

"

=

C

..

<

" <

=

.=

&

"

.,

M

~

"

J

C

=

5

o C

o

C

o

o

=

o .. C - C

narative self-consciousness

narative unconsciousness

Fig. 1: Grading of na ative self-consciousness ( cf Lanser 1 98 1 : 1 77)

This grading according to the level of awareness the narrator has of

his/her own role as narator and of the narrative process shall now be aug

mented by frther categories of analysis. First, the variety of frms in

which metanarration can occur has to be taken into account; and second,

the question of which fnctions these frms of narrative self-refexivity

can flfl has to be addressed.

3. Steps towards a typology ad poetics of metanaration

Although the development of a comprehensive typology and poetics of

metanarration has to await a more extensive study, some aspects of such a

project will be presented in the fllowing survey. This survey, however, is

restricted to identifing the most important sub-categories or types of

metanar ation and the criteria of diferentiation on which the classifcation

is based. Some examples fom literary texts are given to make clear how

varied the types and fnctions of metanarrative expressions can actually

be.

3

8

Ibid.

On Metanarative 21

The fllowing diferentiation of frms of metanarration is based on a

number of criteria mostly adapted fom Werer Wolfs groundbreaking

study Asthetische Ilusion und Ilusionsdurchbrechung in der Erzihl

kunst9, in which Wolf develops a typology of narrative self-refrentiality

that helps to diferentiate between various types of metafction and the

potential efect of each. Wolfs typology is based on three parameters,

"der Vermittlungsfrm, der Kontextbe ziehung und der inhaltlichen

Valenz metafktionaler Passagen'>. The frst criterion, frm of mediation,

refrs to the question of on which level of narration the speaker engaged

in metafctional refections can be situated. According to the second

criterion, contextual relation, diferent frms of metafction can be

distinguished depending on whether they appear in a central or marginal

position, on how deeply they are interrelated wit te narrated story, on

whether they appear only in singular instances or in clusters, and on how

clearly the metafctional aspects of the comment are marked. Using

Wolfs third criterion, contents value, one can diferentiate between

various frms of explicit metafction, i.e. according to the questions

whether metafction refrs to the 'fctio or the fctum status'41

of a

passage, if it contains comments on te entire text or only on parts of it, if

the commentary is on the text itself, on literature in general, or on another

text, and if the discussion of the aesthetic subject takes a rather critical

view of it or not.

The detailed typology that Wolf2 develops on the basis of these

criteria not only flls a gap in research on metafction, but can also be

applied to the feld of metanarration, provided some modifcations and

additions are made. While Wolf is primarily concered with determining

the potential destruction of aesthetic illusion through various frms of

explicit metafction, the main aim of the fllowing considerations is to

develop a set of descriptive categories for analyzing metanarrative

structures as well as fr diferentiating between various types of

metanarration. Out of the large range of criteria that might be relevant fr

a typological diferentiation of various types of metanarration, it 1s

primarily the fllowing which are particulaly productive and relevant.

` Wolf ( 1 993: esp. 220-259). See also Schefel's (1 997: esp. 54- 90) innovative typology

of vaious frs of self-refexive nar ation.

40

Wolf (1 993: 230).

41 Ibid.: 231 .

42 Ibid.: 230f

22

Asga Ninning

Using Wolfs criteria as a stating point, one can distinguish between

dominantly frmal, stuctural, and content-related subcategories of meta

narration. These can then be augmented and diferentiated by reception

oriented and fnctional criteria. Firstly, a frmal distinction can be made

between diegetic, extradiegetic, and paratextual types of metanarration,

depending on the level of communication on which the speaker of the

metanarative comments can be situated. Secondly, structural types of

metanarration can be diferentiated according to the criterion of the quan

titative and qual itative relations between metaarrative expressions and

other pars of a narrated text43 as well as the syntagmatic integration of

such metanarrative passages. Depending on the subject area or te selec

tion of topic, various types of metanarration C be distinguished thirdly,

on the basis of content. Fourthly, a typological diferentiation can be

based on the question of the potential efects and fnctions of meta

naration.

In terms of frm, various types of metanarration ca be diferentiated

according to the questions of what knd of textual speaker self-consciously

discusses the process of naration and on which level of communication

this discussion can be situated. Using the communication level of the

speaker as a staring point, the resulting diference is between dominantly

diegetic and dominantly extradiegetic frms of metanaraton. I the nrst

case, one or more character(s) of the narrated world reflect(s) on the

process of narration; in the second, metanarrative expressions are re

stricted to the narrator, who discusses narrative problems on a higher

communication level. Theoretically, metanarrative questions can also be

thematized in fame narratives or paratextual passages as well as on a

hypodiegetic level of communication. Although the act of narration and

related problems play a signifcat role on all text-interal communication

levels of a narative text, it is particularly the extradiegetic level of dis

course which is of central importance in te present context.

Metanarration is parti cularly obvious in those novels in which the

process of naration is discussed by an extradiegetic narator and in which

it is linked to metafctional expressions. Typical examples of this can be

fund on the one hand in authorally narrated classics like Henry Field

ing' s The History ofTom Jones: A Foundling (1 749), William Makepeace

`` Booth ( 1 952: 1 77) has already diferentiated between "the sheer quantity of [ . .. ]

intrusions" ad "the quality of te interventions" without, however, developing precise

criteria of diferentiation on tis basis.

On Metarrative 23

Thackeray' s Vanit Fair: A Novel without a Hero ( 1 847/48), Anthony

Trollope' s Barchester Towers (1 857) and George Eliot ' s Middlemarch:

A Study ofProvincial Lie ( 1 871/72), in which metanarative passages

have an enormous infuence on the reception process. In many

contemporary novels-such as Julian Baes's Flaubert 's Parrot (1984),

John Fowles' s The French Lieutenant 's Woman (1969), Salman Rushdie' s

Midnight 's Children (198 1 ) and Shame (1983) as well as Graham Swif' s

Water/and (1983)-metanarrative refections also refr primarily to the

extradiegetic level of narrative discourse. In contrast to those novels in

which metanarration is conveyed dominantly extradiegetically, diegetic

types of metanarration are marked by their much higher degree of

integration of the metanarrative refections in the narrated story. Several

examples of this may be fund in many eighteenth-century novels, whose

characters tell their lif stories in the frm of interpolated tales or

embedded stories4, as well as in epistolary novels like Samuel

Richardson' s Clarissa; or, The Histor ofa Young Lady (1 747/48) and

Tobias Smollett' s Te Expedition ofHumphr Cinker (1 771).

In addition to extradiegetic and diegetic frms of metanarration, the

paratextual varieties of metanarration should not be overlooked. In such

cases, the act of narrating is not discussed on the level of story or dis

course but on the level of a fctive editor, by means of fames, chapter

headings or other paratextual devices. Paratextual metanaration is parti

cularly conspicuous in many precursors of the sixteenth- and seventeenth

century novel. In the novels wrtten by Henry Fielding, the majority of the

synoptic chapter headings not only have a metanarative character, they

also contribute considerably to directing the way these novels are received

by flflling many of the fnctions discussed in the fllowing section45

Further examples are the heading of chapter one in B. S. Johnson' s

Christie Malr 's Own Double Entr (1973)-"The Industrious Pilgrim:

An Exposition Without which You Might Have Felt Unhappy"-and te

4 Cf Williams (1 998: chap. 2).

As representative of may other exaples, see, e.g. the fllowing two chapter headings

taken fom Joseph Andrews (1 742) and Tom Jones (1 749): "In which, aer some ver

fne Writing, the Histor goes on, and relates the Interiew between the Lady and

Joseph; where the latter hath set an Example, which we despair ofseeing followed by

his Se, in this vicious Age." (Fielding [ 1 967: 37]); "The Heroe ofthis great Histor

appears with very bad Omens. A little Tale, ofso LOa Kind, that some may think it is

not worth their Notice. A Word or two concering a Squire, and more relating to a

Gamekeper, and a Schoolmaster" (Fielding (1 975: 1 1 8]). On synoptic chapter head

ings, cf. Stanzel (1 982: 58-6).

24 Ansga Niinning

metanarrative refections of the fctive editor Jh Ray, Jr. , Ph.D. in the

freword of Vladimir Nabokov' s Lolita ( 1 955).

A second frmal criterion to distinguish between diferent types of

metanarration is the question whether metanarative comments cross the

border between the levels of story and discourse or not. The diference be

tween metanarration which remains within one communication level on

the one hand and metaleptic frms of metanarration derives fom this. I

the frmer case, the subject of metanarative expressions and the thema

tized object are placed on the same level of communication. I contrast to

this, metaleptic frms of metanarration are chaacterized by a transgres

sion of borders between te extadiegetic level and the diegetic world. The

strategies that Genette includes in the term narrative metalepsis' almost

always have at least an implicit metanarrative character4 Examples of

metaleptic metanaration that tend to have a potential fr destroying the

aesthetic illusion can not only be fund in postmodem novels but already

occur in Laurence Steme' s The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy,

Gentleman (1 759/67).

Thirdly, covert or implicit types of metanarration have to be

distinguished fom explicit frms, a distinction fr which the mode of

mediation can serve as a criterion. All kinds of self-refexive ' directing

fnctions' a narrator flfls draw attention to the process of narration.

Covert or implicit types of metanarration provide the reader, proleptically

or analeptically, with metatextual infrmation, thus creating coherence.

Even if a narrator pretends not to know the story in every detail, s/he

implicitly discusses the act of narration, since this 'pose of partial ignor

ance'47 transfrs the reader' s attention fom the story to the narrator and

the narration. Reader addresses are also implicitly metanarrative if they

render obvious the process of narration or the communication on the

discourse level in an indirect way. Explicit varieties of metanarration,

however, are only present if the act and process of narration is itself di

rectly discussed. Narrators can explicitly thematize the process of nar

ration in diferent ways, intensity, and detail, e.g. when discussing their

behaviour and aesthetic problems.

A furth frmal criterion fr diferentiation is the linguistic frm in

which metanarration is realized. According to this criterion, metaphoric

L Genette ( 1 980: 235): "We will extend te ter narrative metalepsis to all these

trasgressions."

On this pose of the narator in Henry Fielding' s novels, see Fuger ( 1978) and Rolle

(1 963: 85f). For an exaple of a paody of this pose, cf. Trollope (1 975: 24-25).

On Metana ative 25

and non-metaphoric frms of metanarration can be distinguished.

Classical examples of metaphoric characterizations of the narrative pro

cess are the narator's travel and culinary metaphors in Henry Fielding' s

Tom Jones. Further examples can be fund in many later works, e.g. in the

fnal chapter of Sir Walter Scott' s historical novel Waverley; or, 'Tis Sit

Years Since ( 1 8 1 4). A recent example is Adam Thorpe' s experimental

novel Still, in which the narator describes his own narration as a flm

production: "The bit you've missed was vital but I'm not rewinding and

this is a unique screening, so shucks. [ . . . ] This is the trailer, by the way'.8

I non-metaphoric metanaration, conversely, aspects of the narration are

refrred to directly and literally.

Moreover, in order to diferentiate between various types of explicit

metanarration, structural criteria refrring to the relation between the

metanarrative passages of a novel and its other parts have to be con

sidered49. In this context, the position, fequency, and strctural integra

tion of metanarative passages are relevant. Structurally determined types

of metanaration can on the one hand be distinguished according to the

quantitative relations of the metanarative and the non-metanarrative

parts. On the other hand, qualitative criteria like the syntagmatic and

semantic integration of metanarrative refections in the narrated story can

serve as criteria fr a fther typological diferentiation and description of

the various frms of metanarration.

Therefre, the frst question to be asked concering strctural frms of

metanarration is in which position metanarative comments appear in the

novel. With the help of tis criterion, maginal frms of metanaration can

be diferentiated fom central ones. Marginal varieties include those in

which the act of narating is brought up at the beginning or at the end of a

text, a frm which has been common since the Renaissance. Conversely,

metanarrative comments located in more central positions can be fund

within an ongoing story. Examples of works in which refections about the

narration occur primarily in marginal positions are Defe' s novels and

Dickens' s David Coppeiield. While in most novels listed in the bib

liography of this paper, metanarration is already introduced in the frst

chapter, it is also used repeatedly and more fequently in more central

positions. The metanarrative dimension thus plays a much greater role in

48

Thot]e ( 1 998: 2-3).

` L Wolf (l 993: 239f.), who refers to these stucturally defned frs a "[k]ontextuell

bestimmte Typen expliziter Metafktion" ad who diferentiates between various types

of metafctional comments, which will be adapted and modifed in te fllowing.

26 Ansga Niinning

these novels on account of the central position of these self-refexive com

ments and the repeated refections on the narrative process.

Secondly, the quantitative criteria of fequency of metanarrative pas

sages and of their extent compared to the narrated story can help to dis

tinguish between punctual and extensive frms of metanaration. Whereas

' fequency' refrs to the number and regularity of expressions that are

directly concered with the process of narration, ' extent' refrs to the

question of what amount of space metanarrative refections occupy in a

given text. Although both criteria can be diferentiated in theory, they tend

to be intrinsically connected in practice. This is mainly due to te fct that

increasing fequency and increasing extent result in a higher level of im

portance of metanarrative passages. Novels in which a limited number of

metanarrative expressions can only be fund sporadically include most

nineteenth-century realistic novels. Explicit metanarration, however, oc

curs much more fequently and extensively in novels like Fielding' s The

Histor of the Adventures of Joseph Andrews and of his Friend Mr.

Abraham Adams (1 742) and Tom Jones, Wilkie Collins' s The Moonstone

( 1 868) and Adam Thorpe' s Still, all of which can be considered as typical

examples of extensive and marked frms of metanaration. However, their

fnctions may difer signifcantly.

A third structural criterion to diferentiate between various frms of

metanaration is the degree of integration or isolation of the metanarrative

expressions vis-a-vis te narrated story. I the case of integrated frms of

metanarration, there is a close syntagmatic connection between the meta

narrative passages of a text and its other parts, whereas isolated frms are

characterized by a clear-cut division between metanarrative and non

metanarrative passages. A typical example of the non-integrated type is

the fmous chapter 1 3 of John Fowles' s The French Lieutenant 's Woman

( 1 969), in which the authorial narrator suddenly and without prior war

ing destroys the aestetic illusion by means of a metanarrative comment:

"I do not know. This story I am telling is all imagination. These characters

I create never existed outside my own mind"50

In contadistinction to this

clear separation of actal plot and metanarrative commentary, the exten

sive metanarrative refections of the narrators in Stere' s Tristram Shandy

and Stevie Smith' s Novel on Yellow Paper or Work It Out for Yoursel

5

0

Fowles (1977: 85).

On Meta ative 27

(1 936) are inextricably bound up with the discourse as well as with the

story5

1

Closely linked to te question of the degree of syntagmatic connection

is a furth structural criterion, i.e. the degree of contextual plausibility to

which metanarrative refections can be linked up or derived fom the nar

rated story. By means of this criterion, motivated or fnctional and un

motivated or oramental frms of metanarration can be distinguished52

While in the case of motivated metanarration, the action or the discourse

itself provides a plausible reason fr the fct that a narrator or a narrating

character refects about problems of narration, the concept of largely un

motivated or oramental frms of metanarration applies when chaacters

or narrators utter metanarative comments without any obvious connection

between the latter and the events. Metanar ative expressions of the narra

tors are apparently realistically (e.g. psychologically) motivated mainly in

those novels in which the narative process is fregrounded anyway so as

to create the illusion of a personalized narrator or 'teller'-fr example in

Stere' s Tristram Shandy Stevie Smith' s Novel on Yellow Paper, Kazuo

Ishiguro' s The Remains of the Day ( 1 989), and Tibor Fischer' s The

Thought Gang ( 1 994). I contrast to these examples, there are cases of

predominantly unmotivated and isolated metanarrative expressions in

which the reader needs to establish the connection between these com

mentaries and the narated story him- or herself. A case in point is John

Berger s G. ( 1 972), in which the heterodiegetic narator at some points

breaks the primary il l usion of characters and events by using meta

narative and metafctional expressions.

Concering the diferentiation between motivated and unmotivated

frms of metanarration, there are general diferences between homo- and

heterodiegetic narrators as well53 Since a homodiegetic narrator by def

nition tells a story in which s/he is playing a (more or less) central role,

metanarrative expressions can always be set in relation to the narrated

character due to the identity between the narating I and the experiencing I

in homodiegetic naration. Therefre, not only is the narative process of a

frst-person narrator a part of the fctitious world of the characters, but

51 L. A. Ninning (2000).

On the contrast between fnctional and oramental frms of metanaration, cf. Booth

( 1 952: 1 77): "Fielding's narrative devices ae usually fnctional rather tha merely

oraental."

I would like to thank my assistant Klaudia Seibel fr various helpfl comments on the

fllowing passage.

28 Ansga Ninning

his/her narration as well as his/her refections about it are more or less

clearly motivated in the story world. Heterodiegetic narrators instances, in

contrast, report the fctitious happening fom an outsider's perspective.

Since the direct connection to the story level is missing here, meta

narrative expressions of heterodiegetic narrators tend to be less strongly

motivated than those of frst-person narators.

A ffh stuctural distinction can be made between non-digressive and

digressive frms of metaaration on the basis of the degree of digression

fom the narrated story. Although metanarrative expressions tend to result

in momentary digessions fom the narated story, te degree of digression

can vary considerably. Non-digressive frms are usually restricted to pha

tic remarks, prolepses or analepses, or short explanations about the way

the narration is proceeding. Digressive metanarration, by contrast, fre

grounds refections about the act of narrating over quite long passages,

and the narrator' s associations become the dominant principle of coher

ence. If digressions themselves become the subject of self-refexive

expressions, one can speak of 'metadigressive metanarration' . Although

there are several precursors fr tis process, it is Steme' s Tristram Shandy

(especially chapter 22 of the frst book) that is ofen-flsely-refrred to

as the progenitor of this variety54:

For in this long digression which I was accidentally led into, as in all my digressions

(one only excepted) there is a master-stroke of digressive skill, the merit of which has

all along, I far, been overlooked by my reader,-not fr want of penetration in

him,-but because 'tis an excellence seldom looked fr, or expected indeed, in a

digression;-and it is this: That tho' my digessions ae all fir, as you observe,-and

that I fy of fom what I am about, as fa and as often too as any writer in Great

Britain; yet I constatly tae cae to order afairs so, tat my main business does not

stand still in my absence

55

.

Formal and structural diferentiations can be supplemented by content

related frms of metanarration: here, te criterion fr diferentiation is the

object to which the self-refexive metanarrative expressions refr. The

` L, e.g., Tristram Shandy, book I, chap. xxii as well as IX, xiv. It should not be

overlooked, however, that similar frs of digressive metanaration cannot only be

found in Henr Fielding' s novels and those of his predecessors (cf Both 1 952: 1 80f),

but tat there are some exaples of such frs even befre Fielding' s time (cf. , e.g.,

Behn [ 1 930: 205] and Congreve [ 1 930: 250, 260, 274f.]). In Jonatha Swif's A Tale of

A Tub (1 704) a passage (Sect. VII) called "A Digression in Praise of Digressions" even

aticipates Stemeia 'metadigressions' (cf. Swif [ 1 986: 69-72]). On the phenomenon

of the digressive narator, cf. von Poser ( 1969).

55 Steme (1 980: 51).

On Metanarative 29

wide variations of content may help determine the fnctionalization of

metanarration in a given novel. Depending on the subject area and on te

selection of the topics fr discussion, various content-related frms of

metanarration ca be distinguished.

It is obvious that in terms of refrence points of metanarrative

expressions, the possibilities of diferentiation are almost endless; there

fre, this area resists systematization and classifcation, not least because

all aspects and problems of narrating can potentially be discussed in a

self-refexive way. These include refections about the choice and order of

the narated material, justifcations fr leaving things out, thematization of

the way beginnings or conclusions are shaped, refections on the relation

between story time and discourse time5

6

, as well as explanations con

cerning the narrator' s own manner of narrating. The narrator in B. S.

Johson' s Christie Malr's On Double Entr, fr example, comments on

such diferent aspects as the selection, arrangement, and contingency of

the narrated material, on his own manner of narrating, and on the many

repetitions in the narrative discourse. He also makes promises to the nar

ratee, and when he actually flfls the promises after ffty pages, he

proudly emphasizes this fct57: "Here is the story I promised you on page

29, as told to Christie at his Catholic mother' s shapely knee"58

As the preceding discussion has hopeflly served to show, Wolf' s

criteria fr a taxonomic classifcation of explicit metafction provide clues

fr a systematization of certain tyes of metanaration. But to do justice to

te particular contents of metanarrative comments, other categories con

cering the basis of narration and related problems have to be included as

well. Firstly, content-related types of metanarration can b

.

e distinguished

according to the scope of the metanarrative refrences, ranging fom se

lective to comprehensive metanaration. Crucial points here are the the

matic breadth of refrences and the question of in how much detail a text

discusses the act of naration and the problems involved. Selective types

ae characterized by their limitation to a discussion of one or just a fw as

pects of narration. I contrast to this, comprehensive metafction attempts

Cf. , e.g., Tristram Shandy' s refections on time (Tristram Shandy, II, viii; III, xviii) as

well as Trollope, Barchester Towers, chap. 26: "This scene in the bishop' s study took

longer in the acting ta in the telling" (Trollope [ 1 975: 220]).

On the frs and fnction of metana ative utterances in Christie Malry 's Own Double

Entry, cf V. Niinning (2000: 107f).

5

8

Johnson ( 1984: 79).

30 Ansga Ninning

to treat the largest possible spectrum of themes dealing with the act of nar

ration.

A second content-related criterion fcuses on the refrence point of

metanarrative expressions. Self-refexive passages can on the one hand be

restricted to autorefrential comments on the narrator' s own act of nar

rating. Such frms of ' proprio-metanaration' include comments in which

metanarrative refections refr solely to the process of naration in a given

text without any claim to general applicability. On the other hand, meta

narrative expressions can thematize the narrative style of other authors

and texts, or they can refr to the process of naration in general, thereby

claiming a wide applicability. On the basis of these diferent reference

points, one can distinguish between proprio-metanaration, allo-meta

naration and general metanarration5. Other distinctions can be made

between intratextual and intertextual metanar ation, depending on whether

a metanarrative remark refrs to other elements of the same text or to

other texts. The fllowing narratorial comment in A. S. Byatt' s The Biog

rapher 's Tale (2000) gives an example of how closely entangled these

frms can be:

In terms of writing-of the way this story has fnnelled itself into a not unusual shape,

run into a channel cut in the earth fr it by previous stories (and all our lives are partly

the same story, beginning, middle, end)--in ters of writing, this looks like a writer 's

stor. [ . . . ]

So. If I were telling the ' 1 920s' version of Phineas G. Nanson, it would end with an

'epiphany' . (Another frbidden word, though still allowed in Joyce criticism.)60.

A third content-related criterion is the question of which level or aspect

of a narrative metanarrative expressions refr to. In this context, one can

diferentiate between story-oriented and discourse-oriented metanarration.

In the case of the story-oriented variety, self-refexive expressions fcus

on the narated story. Conversely, discourse-oriented metanarration can be

fund in those comments which thematize aspects of the narrative pro

cess. On the basis of this criterion, one can distinguish between speaker

oriented or expressive types of metanarration, phatic frms which relate to

the channel of communication, and reader-oriented or appellative varie

ties. Whereas in the case of expressive frms (which can be fund aplenty

in Henry Fielding' s novels), such self-refexive comments refer primarily

to the narrator, phatic and appellative varieties fcus on keeping the cor-

5

9

These and other English ters used in this paper were coined by Fludemik (2003).

Byatt (2000: 25 1 ).

On Metana ative 31

munication channel up or on addressing the narratee, respectively. Count

less examples of reader-oriented or appellative frms of metanarration can

be fund in Stee' s Tristram Shandy and Stevie Smith' s Novel on Yellow

Paper61 The fllowing brief remark by the psychopatic narrator in Will

Self' s novel My Idea of Fun clearly demonstrates te link between reader

address and metanarration: "When I'm done we'll decide on it together,

you and I. I' ll give you the opportunity to participate in the denouement.

I'm all fr audience participation"62

A furth content-related criterion is the question of whether a meta

narrative comment characterizes the text according to its genre or text

type, leading to a diferentiation between genre- (or text-type-) specific

metanarration and oter frms devoid of such markers. Some examples of

the frst case, in which the ' type' of the narrated story is thematized, ae

the title of the frst chapter in the frst book of Fielding's Tom Jones

("Shewing what Kind of a History this is; what it is like, and what it is not

like"63, the fmous frst chapter of Charlotte Bronte' s novel Shirley ( 1 849)

("If you think, fom this prelude, that anything like a romance is preparing

fr you, reader, you never were more mistaken"64, and the fllowing com

ments of the narator in Byatt' s The Biographer 's Tale, in which the nar

rated story is characterized in a self-refexive way:

I have admitted I a writing a story, a stor which in a haphazad (aleatory) way has

become a frst-person story, and, fom being a story of a search told in the frst-person,

has become, I have to recogiza frst-person stor proper, an autobiography65.

The ffth content-related criterion fcuses on the narrator's assessment

of his/her own narrative competence, resulting in the diferentiation be

tween affrmative and undermining metanarration (i. e. between those

frms of metanarration which express the narrator' s confdence and those

l

Cf, e.g. the fllowing metanarrative prolepses and analepses in Novel on Yellow Paper,

which induces the reader to go backwads and forwad to the respective passages:

"There ae so many people. By ad by I will tell you about them all"; "[ ... ] yea and

even I'll go frther ad say that husbad of hers, whose nae I frgot, though you

fnd it wrten if you tum back a page or two" (Smith ( 1 980: , 1 08).

0?

Self ( 1 994: 1 1). At the end of the novel the nar ator returs to this comment in a fur

ther appellative metanarative utterance: "You what? Oh yes, your oppornity to parti

cipate, silly me, I wa frgetting . . . Well, of course you may, if that what you want but

give it plenty of thought, don't rsh into anything" (ibid.: 304).

63 Fielding ( 1 975: 75).

64 Bronte ( l 974: 39).

6

5

Byatt (2000: 250).

32 Ansga Niinning

frms in which the narator' s insecurity and self-doubt concering the act

of naration become obvious), with many gradual stages in between6 The

authorial narrators in Henry Fielding' s works and in many Victorian

novels are prototypes of the affrmative type of metanarration, whereas

the narrator' s belief in his/her own narrative competence has declined in

many twentieth-century novels. One early typical example of an incom

petent narrator is the servant Gabriel Betteredge in Wilkie Collins's The

Moonstone: despite many attempts, he never really succeeds in telling a

coherent story, and he openly admits his narative incompetence in meta

narrative refections. A particularly extreme example of undermining

metanarration can be fund in Patrick McGrath' s neogothic novel Te

Grotesque (1 989), in which the psychopathic frst-person narator utters

his doubts about his ability to portray events fom the past in a precise, co

herent, and objective manner in one of his many metanarrative self

refections:

So I [ . . . ] try to construct fr you as fll ad coherent an account as I ca of how things

got this way. You must frgive me if I appea at times to contradict myself, or in other

ways violate the natural order of the events I am disclosing; this business of selecting

and organizing one's memories so a to describe precisely what happened is a delicate,

perilous undertaking, and I'm beginning to wonder whether it may not be beyond

6

7

me .

A sixth content-based criterion concers the question of whether and

how each speaker assesses the thematized frms of narration, making fr

the distinction between critical and non-critical frms of metanarration.

Non-critical metanarative comments are those in which no evaluation is

expressed and which are characterized by the narator' s positive attitude

to his/her own narration and to conventionalized narrative frms. I con

trast to this, critical types of metanarration are characterized by a narator

who distances himself/herself fom prevalent conventions or treats them

with irony. This is repeatedly the case in Trollope' s Barchester novels, as

becomes obvious in the narrator's ironic criticism of stereotypical por

trayals and black-and-white presentations in many Victorian novels: "It is

ordained that novels should have a male and a fmale angel, and a male

and a female devil"6 Additionally, the fllowing critical allusions in

As fr as I know, this criterion was introduced by Lanser (1 981 : 1 78), who refes to this

scale as te "ais of self-confdence," with "confdence" and "uncertainty" as its poles.

67 McGrath (1 990: 1 14).

6

8

Trollope (1975: 222).

On Metana ative 33

Barchester Towers to te rigid conventions of the Victorian three-decker

novel stand fr many other examples:

But we must go back a litle, ad it shall be but a little, fr a difculty begins to make

itself maifst in te necessity of disposing of all our fends in the small remainder of

this one volume. Oh, that I might be allowed another!

[ . . . ]

And who can apportion out and dovetail his incidents, dialogues, characters, and

descriptive morsels, so as to ft them all exactly into 462 pages, without either

compressing them unnaturally, or extending tem arifcially at the end of his labour?69

Apart fom the frmal, structral, and content-related criteria, a furth

group of reception-oriented or fnctionally determined frms of meta

narration has to be taken into consideration. Here, the main criteria are the

potential efects and fn<:tions of metanarrative expressions, a difer

entiation which is based on the underlying assumption that an accu

mulation of metanarrative commentaies contributes considerably to a

fregrounding of the narative act and to the creation of the illusion of be

ing addressed by a personalized voice or a ' teller' .

From the point of view of reader-response criticism, te frst question

to be asked is whether metanarrative comments simulate orality or litera

cy. I the frst case, metanarrative expressions evoke the impression of a

speaking voice or fctional orality7

0

, with the narrative process and meta

narrative comments calling up a cognitive schema of an oral com

munication situation or a storytelling fame7

1

In the second case, how

ever, metanarration contributes to portraying the narative act as a writing

process, and, by means of appropriate indications (e.g. paper and pencil),

the materiality of written communication can be emphasized as well.

Whereas the metanarrative dimension in some novels can be clearly

classifed as either fctional orality (e.g. Joseph Conrad' s novels,

Salinger' s The Catcher in the Rye, and Fischer' s The Thought Gang) or

fctional literacy (e.g. Richardson' s epistolary novels, Collins' s The

69 Ibid.: 384, +.

On this efect of faked orality in narative literature, cf. Goetsch ( 1 985) and Griem

( 1 995).

f. Flu

.

derik ( 196: 341 ): "Thus, a holistic understanding of the fae of stortelling

immediately pro1ects a set of dramatis persona on the communicational level (tellers

listeners, i.e. narators and naratees) just a it helps to conceptualize the fictional worl

in ters of a situation and/or plot complete with agents and experiencers, 1. e.

chaacters."

34 Ansga Nining

Moonstone and Byatt' s The Biographer's Tale), metanarative expressions

in Stevie Smith' s Novel on Yellow Paper, Kazuo Ishiguro' s The Remains

ofthe Day and Adam Thorpe' s Sti fature refrences to both oral and

written communication, thus oscillating between both naturalization stra

tegies.

Secondly, one can distinguish between distance-reducing and distance

enhancing frms of metanarration. Despite their highlighting of the act of

narrating, metanarrative expressions of engaging narrators, e.g. the nar

rators of Elizabeth Gaskell' s and George Eliot' s novels, still encourage

te reader to empathize with the characters ad thus reduce te distance to

the fctitious world. I contrast, the metanarrative interventions of distanc

ing narrators, as in Thackeray' s Vanit Fair and Trollope' s Barchester

Towers, have the opposite efect and increase the distance between the

reader and the narrated story72

Depending on the degree to which metanarative expressions destroy

the illusionism of the story and characters, a third reception-oriented dis

tinction can be made between frms of metaarration that are compatible

with the aesthetic illusion and those which destroy it. As I have already

emphasized in the context of the distinction between metafction and

metanarration, metanarrative expressions are not necessarily destructive of

diegetic illusion. On the contrary, the extent to which this illusion is de

stroyed can vary considerably, depending on the specifc character of a

metanarative comment: narrators can use metanarration to reinfrce their

claim to trut according to te convention of realism, or they can render

obvious the constructedness and fctionality of te characters by drawing

the reader' s attention to the fct that any frer plot developments depend

on their arbitrary decision. Forms of metanarration like ' directing fnc

tions', which support the primary illusion, can eiter serve to create coher

ence or they can flfl mnemotechnic, phatic or excitement-creating fnc

tions (cf section 4) without impairing the reader' s illusion. Furthermore,

such metanarative comments can even support the illusion of autenticity

of the narrated story (and of the act of narration). This is particularly the

case in the story-oriented and genre-specifc frms of metanarration fund

in many seventeenth-, eighteenth- and nineteenth-centry novels, in which

metanarrative refections often serve as a prominent authenticating stra

tegy. Since the 1970s, however, metaarrative expressions tend to be a

On the diferentiation between engaging and distancing narators, see Warhol ( 1 986),

( 1 989).

On Metanarative 35

metafctional means of destroying the aesthetic illusion. The destructive

potential of metaleptic frms of metanarration is particularly geat as they

transcend the boundary between the extradiegetic communication level