Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Homo Sapiens, Which Apparently Assumed Its Anatomically Modern Form at Least

Uploaded by

Brent CullenOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Homo Sapiens, Which Apparently Assumed Its Anatomically Modern Form at Least

Uploaded by

Brent CullenCopyright:

Available Formats

!"#$%&'($) +',"(-&./ $-, .#" 01'-'2&13 '4 5-4'(2$.

&'-

!

The pioblem of behavioial moueinity is that of explaining why the species

!"#" $%&'()$, which appaiently assumeu its anatomically mouein foim at least

2uu,uuu yeais ago, only began to manifest behavioially mouein tiaits much moie

iecently, only about 4u,uuu yeais ago. The seiiousness of the pioblem iequiies a

little stage-setting:

The tiaits iuentifieu as components of behavioial moueinity aie geneially

agieeu to incluue abstiact thought, planning uepth, symbolic behavioi, incluuing

language, tool use anu coopeiationcollaboiation. It is iaie foi uistinct capacities

coueu by uispaiate packages of genes to emeige at similai iates ovei a single peiiou,

especially in a mammal ovei a shoit time such that the last 2uu,uuu yeais. Noieovei

almost all complex capacities of the soit iequiieu foi behavioial moueinity must

have aiisen both veiy giauually anu by co-option fiom othei tiaits selecteu foi in

eailiei mammalian oi even veitebiate evolution. So, the uefault piesumption about

the appeaiance of tiaits iequiieu foi behavioial moueinity is that like othei featuies

of !"#" $%&'()$ it must have been a giauual piocess beginning in the common

ancestois of seveial !"#" species. But the eviuence of behavioial moueinity is

iestiicteu to oui species alone, anu appeais only ielatively abiuptly well aftei the

eviuence foi anatomical moueinity.

That theie is a pioblem of explaining the suuuen anu iecent onset of

behavioial moueinity is challengeu by some. Those who ueny that theie is such a

pioblem allege that theie has been a giauual acquisition of behavioial moueinity

insteau of a suuuen onset anu that at least some of the aitifactual eviuence foi it

appeais in the aicheological iecoiu eailiei than 4u,uuu yeais ago [d'Erricoa, 2005 .

Biown, 2uu9j Such eviuence may be incieasing. Bowevei skepticism about its

suuuen onset neeus also to account foi the absence of eviuence of behavioial

!

Thanks to Steve Chuichill, Leonoie Nillei, Baviu Ciawfoiu anu to Kim Steielny foi

uiscussion. The theoiy uevelopeu heie owes a gieat ueal to Steielny's Nicou

Lectuies, 2uu9 anu shoulu not be constiueu as incompatible with his views.

2

moueinity among Neanueithal anu othei !"#" species with whom Bomo sapiens

must have at least biiefly oveilappeu. Even if aicheological uiscoveiies push back

the uate of behavioial moueinity to as much as 1uu,uuu yeais ago, they will not

have entiiely solveu the pioblem, though they will have ieuuceu the tempoial

uimensions of the uisciepancy to be explaineu in oui species.

Natuially these aie not the only two alteinative hypotheses woith

consiueiing. It might foi example be the case that behavioial moueinity anu

anatomical moueinity aie simultaneous, but that aicheological eviuence of

behavioial moueinity oluei than 4u,uuu yeais oi so has not yet tuineu up, has not

suiviveu, oi has been misuateu. Still anothei alteinative is that capacities

subseiving behavioial moueinity have existeu as long as anatomical moueinity but

weie not exeiciseu until !"#" $%&'()$ founu itself faceu with some new

enviionmental thieat that emeigeu only 4u,uuu yeais ago oi so.

This papei aigues that the emeigence of behavioial moueinity is a iesponse

to a single complicateu "uesign-pioblem" that faceu !"#" $%&'()$ anu its ancestoi

species continually ovei the peiiou of its evolution, anu that the uifficulty of the

uesign-pioblem to be iuentifieu explains the absence of behavioial moueinity foi a

long peiiou aftei the onset of anatomical moueinity. The specific natuie of the

uesign-pioblem to be iuentifieu stiongly selects foi just those tiaits commonly

iuentifieu as components of behavioial moueinity. Each of these components of

behavioial moueinity piobably appeaieu in incipient foim inuepenuently anu

iepeateuly ovei the peiiou fiom 2uu,uuu yeais ago but weie lost to uiift. The single

uesign-pioblem will have quite weakly selecteu foi each of them sepaiately, but

only began stiongly to select foi theii co-evolution once all of them weie available in

inteibieeuing populations laige enough to suivive the enviionmental vicissituues of

the eaily anu miuule Paleolithic eia. The conclusion to be uiawn is theiefoie that,

foi a long peiiou aftei the onset of anatomical moueinity the couise of human

evolution, the appioach to behavioial moueinism by one oi moie lineages of !"#"

$%&'()$ is giauual, both veiy slow anu highly vulneiable to extinction thiough uiift.

But then the path to full behavioial moueinity acceleiates iapiuly towaius the veiy

S

enu of the Paleolithic peiiou, as the aicheological eviuence suggest, giving the

appeaiance of suuuen emeigence.

The cential uesign pioblem facing !"#" ovei the peiiou fiom well befoie

the onset of anatomical moueinity is one that is well unueistoou in the

contempoiaiy economics of infoimation. The uesign-pioblem oui ancestois faceu

fiom theii initial emeigence on to the Afiican savannah as scavengeis was the

accumulation, pieseivation, tiansmission of what economists call intellectual

piopeitygoou iueas. uoou iueas piesent a special pioblem to mouein maiket

economies. This same pioblem is magnifieu anu moie uigent when piesenteu to

Paleolithic !"#" $%&'()$.

We can apply seveial featuies of the maiket foi infoimation, foi goou iueas

in paiticulai, anu featuies of the pieiequisites of such maikets both to unueistanu

the uesign-pioblem facing the lineage of !"#" $%&'()$ anu othei extant species of

!"#" with which it coexisteu anu competeu. The economics of infoimation

appioach to the emeigence of behavioial moueinism unifies the suite of factois that

have been suggesteu by competing theoiies as the souices of behavioial moueinity.

In ietiospect it shoulu not be suipiising that the key to the emeigence of behavioial

moueinity in humans shoulu have been the solution to an epistemic pioblem, since

it is intelligence that so obviously uistinguishes us fiom othei piimates anu may

have also been the most significant uiffeience between !"#" $%&'()$ anu the

Neanueithals.

I begin with a biief ieview of alteinative theoiies about the onset of

behavioial moueinism, anu theii weaknesses. Then I sketch a wiuely shaieu

scenaiio foi how cultuially mouein humans evolveu fiom oui ancestois that

iuentifies some of the challenges !"#" faceu anu the solutions to these uesign

pioblems that emeigeu. This fiamewoik pioviues the coevolutionaiy context foi the

long teim giauual oi peihaps suuuen selection of each of the tiaits supposeu by one

oi anothei specialist to be the key to behavioial moueinity. I then outline ielevant

featuies of the economics of infoimation, the uesign pioblem it sets, anu its solution.

This iesult is then applieu to show how it synthesizes togethei the tiaits, iuentifieu

4

as ciucial by competing theoiies, into a unifieu explanation of the onset of

behavioial moueinism.

67 8)."(-$.&%" .#"'(&"3 $-, .#" 31"-$(&' '4 "$()/ #92$- "%')9.&'-

Each of the five components of behavioial moueinity has its own auvocates

as the key to its suuuen achievement.

Seveial anthiopologists have suggesteu that behavioial moueinity of humans

owes its onset to the achievement of abstiact thinking anu planning uepth, owing to

the suuuen appeaiance of cognitive capacities, oi neuiological innovations, peihaps

as a iesult of some genetic mutation. Cooliuge |2uu9j aigueu that the ciucial

uiffeience between !"#" $%&'()$ anu Neanueithals was to be founu in cognitive

function anu memoiy, in paiticulai the piesence in the lattei of a mouein "executive

function" along with a much laigei woiking memoiy anu a subvocal phonology.

These chaiacteiistics enableu oui ancestois to engage in ueep planning, the cieation

of innovations anu theii application to new contexts. By contiast Neanueithals weie

limiteu to expeitise anu leaining by close appienticeship. Klein |2uu2j opts foi a

neuial genetic mutation that iesult in cognitive enhancements pioviuing

consciousness, symbolic thought anu piesumably soon aftei it, language, but he is

silent on any uetails. Nithen |!"""# similaily suggests that at some point an

inuepenuent set of cognitive skills began to communicate with one anothei in oui

biains, piobably as a iesult of the emeigence of public speech anu then silent

monologue.

Some obvious uifficulties anu imponueiabilties attenu these theoiies. uenes

coue foi pioteins, not foi cognitive tiaits. The appeaiance of a new cognitive tiait

owing eithei to mutation in a single geneiegulatoiy oi stiuctuialwoulu be

unpieceuenteu in mammalian genetics. The likelihoou of simultaneous oi neai

simultaneous mutations, uuplications, anu othei changeu in a suite of genes laige

enough to effect iapiu changes in cognitive skills is unlikely. Such eviuence as has

been auvanceu foi a selective sweep thiough the population of neuial genes in

ioughly the ielevant time peiiou has pointeu to genes that aie ielateu to biain size

in geneial, not specializeu molecules oi uistinctive capacities |Evans, et. Al., 2uuS,

S

uilbeit, et al. 2uuSj . Noieovei, as Steileny |2uu9j has pointeu out theie appeai to

be iegions such as Tasmania in which behavioial moueinity has been lost ovei time

among small populations without any impaiiment in theii cognitive functions. So

the emeigence of these functions cannot have been sufficient foi behavioial

moueinity.

In geneial the emeigence of complex auaptations of the soit these theoiists

piopose is long-teim, giauual, often beginning with one oi moie pieauaptations foi

othei pioblems anu then being co-opteu, combineu, anu fine tuneu ovei a long

peiiou in which selection can opeiate on inuiviuual piotein couing- anu stiuctuial -

genes. Theie is some eviuence foi "mastei contiol genes" in mammalian

neuiophysiology%&'(')) is one example. But these genes which switch on cascaues

that piouuce complex stiuctuies emeige long befoie natuial selection piouuces

paiticulai neuial stiuctuies. Selection foi any tiait now iecognizeu as a uistinctive

human cognitive ability will have to have opeiateu on a laige suit of genes at the

ioughly the same time ovei a shoit peiiou. In the absence of any eviuence foi such a

piocess, anu piobably some counteieviuence in the foim of uiffeient mutational

ages foi the ielevant genes, the suggestion that behavioial moueinity is uue to a

suuuen genetically coueu cognitive change Su,uuu yeais ago must be ueemeu

speculative.

An eailiei tiauition iuentifies bieak-thioughs in tool making anu the uses to

which tools weie put as the tiiggei foi iapiu achievement of behavioial moueinity

by a species that hau been anatomically mouein foi the pievious 1Su,uuu yeais.

This hypothesis is beuevileu in pait by the "eviuence of absenceabsence of

eviuence" pioblem all evolutionaiy theoiies face. Is the absence of complex tools

fiom the one million yeai iecoiu piioi to 2uu,uuu yeais ago eviuence that they hau

not been iepeateuly inventeu anu lost. Is the eviuence of suuuen expansion in

mateiial, complexity in uesign anu oiganization of use aftei Su,uuu yeais ago also

eviuence that it was absent befoie then, oi is it a ieflection of aicheologist's looking

in the wiong places oi theii bau luck oi uifficulties of pieseivation owing to climate,

geology anu composition. Still anothei uifficulty with the theoiy is the fact that as

aicheology moves noith into moie hostile enviionments, moie complex tools of the

6

soit chaiacteiistic of behavioial moueinity aie to be founu. So, peihaps the absence

of such tools in moie tempeiate iegions befoie Su,uuu yeais ago simply ieflects the

absence of much neeu foi them, at least until enviionments changeu anuoi human

populations giew laige enough to iequiie moie complex technologies. If so,

behavioial moueinity might be pusheu back many tens of thousanus of yeais,

theieby ieuucing the appaient uiscoiuance between anatomical anu behavioial

moueinity.

In any case the technological ievolution hypothesis begs the question of the

onset of behavioial moueinity. Foi suiely the tools weie not simply paiachuteu into

the Afiican continent. They aie symptoms, not causes of whatevei giauually oi

suuuenly piouuceu behavioial moueinity. Avoiuing this pioblem is piesumably

what makes the cognitive ievolution hypothesis biiefly exploieu above so attiactive.

The acquisition of language, symbolic capacities, anu the abstiact thinking

that piesumably cannot be unueitaken without it is often citeu both as a piioi

necessaiy conuition foi complex tool uesign, manufactuie anu employment, anu

equally often iuentifieu as the iesult of some ievolutionaiy cognitive uevelopment

iesulting fiom neuiogenetic causes, peihaps tiiggeieu by some (set of) extieme

uesign pioblem(s) facing !"#" $%&'()$ just befoie the emeigence of behavioial

moueinity. 0ne attiactive canuiuate foi such uesign pioblems was the combination

of the (peihaps incieasing) inability of humans to suivive in small gioups coupleu

with the inability (common to many piimates) of genetically unielateu inuiviuuals

to cohabit peacefully in laige numbeis in a small iegion. Bowevei solving this

uesign pioblem by ueveloping the capacities not meiely to coopeiate as othei

piimates uo, but to collaboiate, iequiies shaieu intentionality |cf. Beimann, 2uu7j.

But this is itself a pioblem which must be solveu at least a little bit befoie the onset

of symbolic communication. Foi communication notoiiously is alieauy a mattei of

noims anu nesteu intentions with iespect to them that pie-iequiies collaboiation

anu a stiong theoiy of othei minus.

The iole of language in human evolution, its suspecteu absence fiom

competing species such as the Neanueithal, anu its ieliance on pievious solutions to

pioblems of complex anu especially seiial (as opposeu to simultaneous oi neai

7

simultaneous) coopeiation anu collaboiation, natuially suggests that it was solving

the uesign pioblem of coopeiation suuuenly anu effectively about Su,uuu yeais ago

that tiiggeieu behavioial moueinity. This appioach exploits theoiies such as

Bingham's |1999j, accoiuing to which the key to coopeiative social gioups was the

ability to iemove (oi iestiain) uncoopeiative but poweiful inuiviuuals by low iisk

iemote killing. Bingham explicitly iuentifies coalitions anu coopeiation as

pieiequisites foi language, anu iightly emphasizes the neeu to enfoice honesty,

without which symbolic conventions coulu nevei have aiisen. But the soit of

coopeiation iequiieu must have emeigeu long befoie the ieliable piojectile

weapons-- that make iemote killing possible. Eviuence of thiusting speais goes back

to well befoie behavioial moueinity, anu it is cleai that theii use in mega fauna

pieuation (oi piotection fiom them) alieauy iequiies cooiuination of seveial

hunteis uoing uiffeient things collaboiatively at the same time. Fuitheimoie,

uomestic anu iepiouuctive coopeiation, incluuing the uivision of laboi, between

males anu females has little to uo with piojectile weapons, noi aie they obvious

paits of the coopeiation iequiieu foi teaching, appienticeship anu the moie

impoitant uivision of laboi in tool making. Noieovei, in veiy small gioups of closely

ielateu kin the enfoicement pioblems Bingham iuentifies as obstacles to behavioial

moueinity aie not even supposeu to aiise.

It is ceitainly ieasonable to holu that all of these innovationsabstiact

thinking iesulting fiom cognitive enhancement, tool making, language anu

collaboiationset in giauually as uiveise solutions to multiple uesign pioblems.

Components of each of them might have hau a genetic basis anuoi that Baluwin

effect |Webei anu Bepew, 2uuSj piocesses coulu have maue them incieasingly easy

to leain on the basis of veiy little enviionmental piiming. Nost impoitant, small

impiovements in each coulu have co-evolveu with anu enviionmentally enhanceu

the iate at which the otheis weie selecteu foi, so that at a ceitain point, the whole

package became stiong enough to suuuenly achieve behavioial moueinity. But foi

such a piocess to have opeiateu theie must be some common factoi, an

enviionmental foice, a majoi uesign pioblem, to oichestiate the co-evolution of

these human tiaits. Noieovei, cumulative appioaches to a solution to such a unique

8

peisistent uesign pioblem will not piouuce a suuuen aiiival of behavioial

moueinity, but iathei a giauual one, somewhat at vaiiance with the histoiical anu

compaiative uata.

0ne scenaiio foi the bioauest lines of the evolutionaiy foices which shapeu

!"#" $%&'()$ has the following sequence: Initially, some pieuecessoi of oui

species left the iain foiest, peihaps as a iesult of competitive exclusion foi the

Afiican savannah just befoie oi uuiing a peiiou of cooling anu uiying. Beie the

immeuiately available foou souices weie what coulu be scavengeu fiom the coipses

left by cainivoious anu uangeious mega fauna. Because the maiiow in caicass

bones was inaccessible to mega-pieuatois it constituteu an available piotein iich

foou souice if it coulu be accesseu. This souice of nutiients put immeuiate selective

piessuie on the uevelopment anu use of the simple hanu axe.

0nce inventeu, the axe pioviueu foi a significant inciease in available piotein

to this species of !"#". Incieaseu piotein pioviueu an enviionment which selecteu

foi incieases in biain size anu in cognitive skills that maue tiacking anu killing mega

fauna piey possible. It may also have begun the piocess of enhancing collaboiation

within genetically ielateu lineages to piotect kills fiom othei pieuatois anu even

begin to fostei uivision of uomestic laboi. Incieaseu biain size continueu to have all

of these effects, but aftei a ceitain point began to select foi anatomical changes in

the pelvis of females anu foi biith at an eaily level of cianial uevelopment along

with a long peiiou of infancy anu chiluhoou. Continueu incieases in oi peisistence of

a piotein uiet selecteu foi fuithei cognitive sophistication, anu this togethei with a

long chiluhoou pioviueu the oppoitunity foi anu the auaptational value of extenueu

peiious of teaching, appienticeship, anu piactice, both in tool making anu tool use.

These in tuin again enhanceu piotein uiet both fiom fuithei impiovements in mega

fauna foiaging anu fiom gatheiing of nuts anu tiapping smallei piey. Each of these

auaptational achievements both enhanceu the effectiveness anu efficiency of

pievious auaptations anu pioviueu the ciicumstances in which theie was selection

foi fuithei auaptational novelties. Anu not just genetically encoueu auaptational

novelties, but at this point cultuially tiansmitteu ones too, especially ones exploiting

the oppoitunities pioviueu by extenueu chiluhoou uepenuence anu its consequent

9

oppoitunities foi leaining. Thus the tool making anu tool using iepeitoiie of these

!"#" ancestois expanueu peisistently though eviuently veiy slowly ovei a million

yeais oi so.

This scenaiio of the appeaiance of auapteu tiaits shoulu not be vieweu as a

step wise piocess . Rathei, the effects each of the tiaits hau on fuithei selective

shaping of all of the othei ones, which in tuin eventually shape the oiiginal one,

constitutes a coauaptational feeu back cycle in which no one step aftei the initial

uiscoveiy of scavenging on the savanna can be iuentifieu as moie causally

significant than any of the otheis. Inueeu, to even think of the piocess as involving

steps in which only one of these tiaits is shapeu by selection will be wiong. Baving

begun a million yeais ago oi moie, the cycle spiials thiough an incieasing numbei of

inuepenuent lineages (oi bushy families) ovei anu ovei at painfully slow iates

making at best veiy small steps towaius behavioial moueinity, anu mostly leaving

no uetectable eviuence ovei veiy long peiious.

This scenaiio anu most otheis like it, howevei, put a piemium on

infoimational pieseivation anu tiansmission acioss geneiations. If behavioial

moueinity is the iesult of such a scenaiios, it must solve pioblems of infoimation

acquisition, stoiage anu tiansmission, pioblems faceu at the outset, when !"#"

fiist faces a well-eaten caicass with nothing much left to feeu on but the maiiow

insiue the long bones. These infoimational pioblems !"#" faces in meeting its

initial infoimational neeus aie $+%,,(-'),./ 0'11'23.+, owing to the natuie of

infoimation anu its economics. They aie so haiu to solve that we shoulu expect a

million oi so yeais to elapse befoie they aie peimanently solveu. Noieovei,

anything even close to an appioximate solution, fiom the point of view of the

economics of infoimation, pietty much iequiie the tiaits of behavioial moueinity.

This is what makes the economics of infoimation so potentially illuminating a

theoiy foi the unueistanuing of human evolution.

:7 ;'', -"< &,"$3 $-, .#" "1'-'2&13 '4 &-4'(2$.&'-

1u

In economics a public goou is one that has two piopeitiesnonexcluuability

anu non-iivalious consumptions. Public stieet lighting is a cleai example: I can't

enjoy its secuiity, even if I am the only one paying foi it, unless otheis can uo so at

the same time. I can't excluue them except by tuining off the light. Ny consumption

of the safety anu secuiity stieet lighting pioviues uoes not ieuuce the amount of

secuiity-lighting available foi otheis. When it comes to public goous, consumption is

not a zeio sum game. These two featuies pioviue iational agents an incentive to

fiee-iiue when calleu upon to pay theii shaie of the public goou's cost. The

piovision of public goous among iational agents is theiefoie usually maintaineu by

social coeicion in the case of small gioups of peisons know to each othei anu by

political coeicion in laige gioups.

uoou iueas aie veiy like public goous: the consumption of them is non-

iivalious: if I engage in cioup iotation to inciease yielus, that in no way ieuuces the

amount of that goou iuea that you can use, noi uoes it effect the yielu that woulu

iesult fiom youi use of it. 0nlike public goous, goou iueas aie excluuable, but it is

often uifficult anu costly to excluue otheis fiom using them, The most common

methou of exclusion is to use the iuea in seciet, but this imposes seciecy costs anu

often cannot be uone at all. Imagine attempting to iotate ciops in seciet: possible

but uifficult anu ceitainly uisauvantageous.

Like public goous we can theiefoie expect goou iueas to be pioviueu in a fiee

maiket at suboptimal levels anu when they uo emeige to be the focus of too much

investment to keep them seciet. In fact, the investment in piovision of goou iueas in

a competitive maiket is likely to be seiiously suboptimal. Few will invest in ieseaich

anu uevelopment since the iisks of loss may be consiueiable anu otheis cannot be

excluueu fiom the benefits of uiscoveiy. Ciop iotation is a goou example. If I tiy it

anu it uoesn't woik, I stanu to lose a gieat ueal of income. If I tiy it anu it woiks,

then otheis can auopt the technique too with benefits equal to mine, without having

investeu in its uevelopment oi iiskeu theii output to tiy it out. Accoiuingly, no

iational agent shoulu invest in uiscoveiing oi inventing goou new iueas, but each

shoulu keep a watchful eye on otheis in case they hit upon a goou iuea by

seienuipity so they can use it too. 0n the othei hanu, when a iational agent hits

11

upon a goou iuea seienuipitously iuea but away fiom the sight of otheis, the iational

agent shoulu invest in keeping it seciet, at least up to the competitive benefit it

pioviues him oi hei.

The usual contempoiaiy solution to this pioblem of unueiinvestment in

ueveloping goou new iueas anu oveiinvestment in using them, is of couise the

patent iighta limiteu teim monopoly iight to sell use of the iuea given by a

goveinment to a uiscoveiei oi inventoi in exchange foi full uisclosuie so othei

agents can benefit by it (up to the piice of use). This is an impeifect solution but no

bettei alteinative has been founu that appioaches moie closely to allocative

efficiency in the uiscoveiy anu employment of goou iueas.

Economists infei fiom theii mouels of iational choice anu the natuie of goou

iueas as neai public goous that in the long iun the absence of an enfoiceu piopeity

iight in goou iueas iesults in unueiinvestment in piovision anu oveiinvestment in

use of these goous. Fiom the peispective of institution-uesign, intellectual piopeity

is, like othei foims of piopeitychattel anu ieal--the solution to an incentive

compatibility pioblem: the pioblem is uesigning institutions that enable a society to

hainess the self-inteiest of its citizens to the attainment of some geneial benefit to

all of them. Typically, a society neeus noims that will enable it to economize of

scaice common iesouices that inuiviuuals has incentives to ovei-use oi unuei-

piouuce. 0f couise the socially optimal employment of piivate iesouices, whethei

ieal oi chattel piopeity oi intellectual piopeity oi special capacities anu abilities,

also iequiies the establishment anu enfoicement of noims necessaiy foi ieliable

tiaue. Among these aie noims enfoicing the completion of tiansactions once agieeu

to. When these noims aie fully inteinalizeu high tiansaction costs such as exchange-

policing oi insuiance aie not imposeu. In othei woius, tiust is iequiieu at seveial

places in the opeiation of any exchange economy, anu as we shall see is even moie

ciucial to tiaue in exchanging intellectual piopeity.

0f special impoitance to maikets in goou iueas aie those featuies which

fostei the uivision of laboi anu enhance its effectiveness. Recognition of some of the

conuitions that fostei the uivision of laboi go back to Auam Smith. But the piovision

12

of intellectual piopeity is paiticulaily sensitive to the conuitions which fostei the

uivision of laboi.

The uivision of laboi, as Smith was among to fiist to iecognize, enhances

piouuctivity, but is in his woius "limiteu by the extent of the maiket": the moie

people tiauing in moie goousincluuing piouuctive inputs, anu not just consumei

goous, the moie scope foi the uivision of laboi anu foi enhancements in

piouuctivity, anu *+,' *'-).. Auuitionally, the uivision of laboi anu the iisks

associateu with specialization inciease togethei, anu iequiie the solution to a

seiious "tiansaction cost" pioblem, one which, accoiuing to Ronalu Coase |Coase,

19S7j iesults in the emeigence of fiimsthat ieuuce such costs when they binu

togethei highly specializeu inuiviuuals engageu in piouucing goous which have

value only when joineu togethei. The peisistence of fiims of couise iaise a laige

numbei of othei pioblems of institution uesign anu noim

establishmentenfoicement foi a society.

It iequiies only a little thought to iecognize that any one whose piinciple

activity involves the cieation, iefinement, stoiage anu communication of goou

iueaseven when accoiueu status as piopeityhas a paiticulaily seveie veision of

the uivision of laboi pioblem. Foi what this specialist tiaues in is not even a

conciete object, let along one which pioviues a necessity of lifefoou, sheltei,

clothes, waimth, etc. Iueas aie abstiact. No mattei how much a goou iuea enhances

piouuction of conciete consumption goous, abstiact iueas uo not "exist" in space oi

time. Even when iepiesenteu in conciete mental states, oi theii insciiptions anu

images on papei oi maiks uiawn in the sanu, oi on cave walls foi that mattei, goou

iueas cannot by themselves be uiiectly consumeu, anu will not suppoit human life

without a substantial maiket in which to tiaue them. Specialists in the pieseivation,

anu tiansmission of goou iueas aie in the same boat as theii cieatois when it comes

to the neeu which the uivision of laboi iaises foi a ielatively laige maiket.

What uoes this have to uo with the emeigence of behavioial

moueinity. Peihaps a gieat ueal. If goou iueas aie iequiieu foi the initial suivival of

!"#" anu its subsequent evolution, then the economics of infoimation sets a much

moie uifficult uesign-pioblem than is set by the pioblems of the optimal piovision

1S

of chattel piopeity anu the pioblem of the uivision of ieal piopeity. Anu the moie

seveie pioblem it sets must be solveu 4(1"-( gioups solve the easiei pioblem of the

optimal piovision of chattel piopeity anu uivision of ieal piopeity. If the haiuei

pioblem comes fiist, then solving the easiei pioblem can't be a step on a giauual

path to solving the haiuei pioblem, anu the haiuei one is a baiiiei to the easiei one.

0nuei these ciicumstances a long uelay aftei the onset of anatomical anu

specifically cognitive moueinityabstiact thought, planning uepth, symbol use,

language, coopeiationcollaboiation.

=7 >'<"( ?$)"')&.#&1 !"#" 1$-@. 3')%" .#" 2'3. A$3&1 "1'-'2&1 B('A)"2 '4

&-4'(2$.&'-CB("3"(%$.&'-

It took moie than 2,uuu,uuu yeais foi !"#" to move fiom somewheie neai

the bottom of the savanna's cainivoious foou chain to the veiy top. The bottom was

scavenging coipses felleu by pieuatois initially highei up in the foou chain than oui

ancestois. Scavenging iaises two pioblems: how to chase away the pieuatois that

biought uown the piey, anu how to extiact nutiients fiom the felleu piey. Inability

to solve the fiist pioblem exaceibates the seconu, since little will be left to scavenge

if the fiist pioblem cant be solveu. It can't be solveu when the pieuatoi is a

cainivoious feline, foi example, anu gioups of scavengeis aie small in numbei, tool-

less anu uisoiganizeu. At this point in the eaily stone age, the only thing !"#" hau

going foi itself was that those inuiviuuals who scavengeu togethei weie piobably

closely ielateu kin.

Small gioups of Lowei Paleolithic !"#"/ piesumably unable to ieliably solve

the pioblem piesenteu by pieuatoi-mega fauna, coulu only have suiviveu if they

solveu the seconu pioblem: secuiing nutiients left by the pieuatoi: this is wheie

seienuipity oi genius intiouuceu a goou iuea: the hanu axe to bieak maiiow bones.

Since populations weie low, banus weie small, anu extinction thieats gieat anu

pievalent, it is safe to assume that

a) lines of !"#" -uescent eithei aiiiveu in the savannah with the iuea of the hanu

axe anu how to make it,

oi

14

b) this iuea was hit on inuepenuently by multiple lines of uescent when faceu with

the pioblem of ieliable access to maiiow.

If the iuea of a hanu axe to bieak such bones hau been hit on only once, it woulu

piobably have uieu out with its cieatoi's lineage owing to the high extinction iates

of inuiviuual isolateu lineages on the savanna. Low populations unuei continual

extinction thieats cannot solve the knowleuge pieseivation pioblem foi long

peiious. Accoiuingly, the eailiei the hanu axe emeigeu, the laigei the numbei of

inuepenuent innovations it piobably hau. In fact, we have goou ieason fiom

piimate-obseivation to suppose it was alieauy in hanu when !"#" aiiiveu on the

savanna. 0nce it became sufficiently common among lineages, the iuea of the hanu

axe's chances of becoming extinct, along with any one paiticulai lineage that

possesseu it, weie ieuuceu. If the hanu axe solveu the pioblem of scavenging well

enough, then it leu to a population expansion in the lineages that possesseu it which

incieaseu its likelihoou of suivival, anu it leu to an inciease in that populations

souice of biain-suppoiting piotein.

Pieseivation, accumulation, augmentation of the suite of hanu axe-iueas

both manufactuie anu use components-- iemains piecaiious unuei conuitions of

low population foi a seconu ieason.

In small populations, oppoitunities foi even low levels of any kinu laboi-

uivision aie iaie. Specializing in any consumption goou iequiies that otheis

piouuce anu tiaue in all othei consumption goous neeueu foi suivival, anu

specializing in an inteimeuiate piouuction goou iaises the fuithei pioblems of, fiist,

assuiing that otheis pioviue the othei components it "uove tails" with to make a

consumption goou, anu seconu, that someone combine the specializeu in puts, tiaue

the finisheu consumption goou anu pay all inteimeuiate goou piouuceis foi theii

woik . The cooiuination pioblems that neeu to be solveu by the uivision of laboi in

chattel piopeity oi seivices is eviuently consiueiable. Some of these pioblems will

have to be solveu almost fiom the stait of human evolution to ensuie the uomestic

uivision of laboi between males anu females. At least in small populations anu

within nucleai families the enfoicement pioblems of a maiket aie piesumably

soluble thiough the mechanism of kin-selection enfoiceu altiuism. But fuithei

1S

uivision of laboi iequiies laigei populations anu laigei populations uilute genetic

ielateuness anu inciease the tiaue-enfoicement pioblems iaiseu by the

cooiuination neeus of successful uivision of laboi.

The pioblems that confiont the uivision of laboi aie much moie seveie

howevei, when the uivision of laboi is not between piouuceis of chattel goous

alone, but the uivision of laboi is among piouuceis of chattel goous on the one hanu

anu those who piouuce, accumulate, stoie anu tiansmit goou iueas on the othei.

Consiuei the succession of innovations in hanu axe technology: mateiial-choice,

coie shape choice, flaking, bi-facial flaking, heat tieatment, compounu axe making.

No one can iisk specializing heavily in uiscoveiy, pieseivation, impiovement,

tiansmission (teaching) of goou iueas in hanu axe technology when the "maiket" foi

these iueas is veiy small . At the outset when goou iueas aie easiei to come by, this

is less of a pioblem: if eveiy one is a close kinsmen, all aie knowleuge-

pioviueisbeaieisteacheis, anu exclusive knowleuge is haiu to piotect, exchange

will be common.

But goou iueas aie abstiact objects, not conciete ones. When populations

become laige enough foi this soit of uivision of laboi, obstacles to tiaue emeige. Not

only is enfoicement of exchange noims iequiieu when tiaueis aie not closely kin-

ielateu, but the natuie of goou iueas as abstiact objects is a majoi baiiiei to

exchange. 0ften making the existence anu chaiactei of a goou iuea known iequiies

giving them away, which abolishes the incentives to tiaue chattel piopeity foi them.

0nce given to one oi moie useis, a goou iuea cannot be taken back on non-payment,

anu of couise theie is no iewaiu to the oiiginatoi (anu no loss to the iesellei) if the

iuea is iesolu to a Su paity.

Notice that tiaue in chattel piopeity is itself a goou iuea, as is the veiy notion

of the uivision of laboi, anu the uivision of laboi between piouuction of goou iueas

anu chattels. Insofai as the piactice of exchange of chattel piopeity, the uivision of

laboi oi the uivision of laboi between chattels anu goou iueas was itself an

infoimational innovation, anu not just the emeigence of a piactice that hau

seienuipitous benefits, they themselves piesupposeu a piioi solution to an

economics of infoimation piobleminventing, intiouucing, pieseiving, anu figuiing

16

out how to enfoice these institutions in the absence of piioi institutions of tiaue of

any kinu. The solution to the pioblem in pioviuing goou iueas is some soit of a

maiketi.e. enfoiceu iules of exchange, but this is itself a goou iuea whose

piovision pie-iequiies that something like a maiket alieauy be in existence. The

same goes foi the iueas of the uivision of laboi anu the uivision of cognitive anu

physical laboi, etc. When one consiueis how foimiuable weie the obstacles to the

establishment of patents iights, low long anu how many nations uiu without them,

anu how pooily they aie enfoiceu even touay, the uimensions of the pioblem of

insuiing anything like the optimal piovision of even ielatively goou iueas in eaily

human evolution must be veiy gieat.

D7 E"< 01'-'2&13 '4 5-4'(2$.&'- ?('A)"23 &- .#" ?$)"')&.#&1

So long as the population is closely kin-ielateu, it uoes not iequiie a maiket

oi agencies to enfoice noims of exchange on paiticipants in a maiket. Natuial

selection foi selfish genes will finu ways to builu psychological enfoicement

mechanisms. As it uoes so, a co-evolutionaiy cycle begins, involving incieaseu

piotein consumption, incieaseu cognitive capacity, incieaseu technological

innovationboth in piouuction anu use, fuithei incieases in piotein consumption

anu its consequences foi anothei iounu of innovation, along with othei changes

such as shoitei gestation, longei chiluhoou, anu oppoitunities to instiuct, etc. This

cycle shoulu not be imagineu to move at a iate much above one ievolution pei

1uu,uuu yeais oi so, at least to begin with. Neveitheless, it will be uiiven by

selection foi solution to institution-uesign pioblems iuentifieu in the economics of

infoimationassuiing auequate ietuins to the pioviuei of an abstiact goou that is

non-iivalious anu haiu to excluue. Anu the small population will seveiely limit the

extent of the maiket anu theiefoie the uegiee of uivision of laboi between the

piouuction of chattels anu goou iueas.

But, unuei these ciicumstances, the invention of the compounu axe may well

be uelayeu foi much of the million yeais aftei the hanu axe came into use, may have

been iepeateuly inuepenuently inventeu anu lost at an acceleiating iate ovei that

peiiou, anu finally only become a secuie innovation at the population size of !"#"

17

only as late as the Nesolithic, fiom which eviuence of compounu tools has been

iecoveieu. Let's use the thiusting speai, the compounu axe, anu the suite of iueas

iequiieu to builu anu use them, to puisue the way in which the economics of

infoimation stiuctuies the uimensions anu the oiuei in which !"#" hau to solve

uesign pioblems foi suivival long enough to evolve into us.

The hanu axe, anu even impiovements in it like b-facial flaking, may have

been hit upon by acciuent. The thiusting speai iequiies a minimum amount of point

woiking, anu when fitteu with a stone-point iequiies technology as complex as the

compounu axe. What noims must have been honoieu by membeis of a kin-gioup in

which the iuea of the thiusting speai anu its use was pieseiveu long enough to come

uown to us. Whatevei noims they aie, they may not have been sufficient to

pieseive the thiusting speai at the low levels of population which kin selection

iequiies to maintain unenfoiceu noims of exchange. Nost piobably "luck"uiift

was involveu as well, since the iuea occuis multiply anu appaiently inuepenuently

in the aicheological iecoiu.

0ne obvious noim honoieu by such gioups involves hoiizontal anu oblique

tiansmission of the goou iueathose who tiansmit it must uo so uiiectly oi

inuiiectly to the all the kin-gioup's chiluien, not just theii own, if the iuea is not to

be lost. They must have oppoitunities to innovate, expeiiment, anu take some

uesign iisks in uoing so. Teaching anu expeiimenting can't ieuuce theii inuiviuual

fitness, even when it impinges on theii available scavenging, anuoi hunting time.

Accoiuingly theii kin will have to obseive noims of iecipiocityshaiing iesouices

oi otheiwise compensating teacheis anu ieseaicheis with chattel goous foi non-

iivalious uifficult to excluue abstiact objects anu foi seivices in ueliveiy of abstiact

objects.

The thiusting speai is a goou iuea that opens a wiue iange of piotein

iesouices to a lineage hitheito limiteu to scavenging coipses in which pieuatois aie

no longei inteiesteu. 0nce on the scene, the thiusting speai will enable a gioup of

scavengeis to uefenu themselves against pieuatois, anu to foice pieuatois away

fiom theii kills befoie all the available flesh has been consumeu. This makes foi

anothei substantial inciease in piotein anu so acceleiates the co-evolutionaiy cycle

18

in which it is a factoi. But the thiusting speai's use iequiies that the lineage solve

the pioblem of cooiuinateu use, along with the pioblem of pieseiving anu

tiansmitting the technology of speai piouuction. Theie is inuepenuent eviuence that

the shaieu intentionality iequiieu foi such cooiuination is beyonu the cognitive

capacities of chimps anu available in human infants as eaily as the age of 2

|Beiiman, 2uu7j . Theie must have been stiong selection against those !"#"

species which lackeu this capacity, anu stiong selection foi the enhancement of even

a iuuimentaiy shaieu intentionality. Ninimal levels of this capacity aie iequiieu

both in the cooiuinateu use of thiusting speais anu in teaching theii use. Anu these

achievements both piesuppose piioi oi simultaneous uevelopment of noims that

enfoice collaboiation in the solution of the complex uesign pioblem poseu by the

neeu to oi the auvantage of uiving laboi, anu uiviuing it between piouuction of

abstiact anu conciete objects. The level of cooiuination involveu in these two levels

of uivision of laboi is piobably highei than that iequiieu foi the cooiuinateu use of

the thiusting speais that the uivision of laboi pioviueu!

It appeais that maximum size among huntei-gathei gioups is 1Su inuiviuuals

oi so, aftei which gioups appeai to fission. At such sizes, kin-ielateuness is too low

to iewaiu those specialists who pioviue goou iueas to all membeis oi teach all the

gioup's chiluien, with sufficient inclusive fitness foi such specialization to peisist.

What is neeueu of couise aie noims that encouiage oi iewaiu the specialist's

knowleuge by enhancing his inuiviuual fitness. Nany uiffeient schemes will achieve

this enu, incluuing accoiuing status to savants oi iecipiocal exchange of conciete

goous foi piovision of goou iueas to otheis. But it is eviuent that once the uivision of

laboi in the innovation of goou iueas has gone even a little way, such teaching also

iequiies cognitive competences alieauy beyonu those of othei piimates. Leaineis

will have to be goou at imitation, anu teacheis goou at teaching, anu both goou at

collaboiative inteiaction.

The pay-off to even ielatively simple capacity foi veibal communication in

oiuei to actually shaie incieasingly complicateu intentionalityplans, stiatagems,

tool-making methous, etc. is obvious anu aftei a ceitain point it becomes

inuispensible foi the attainment of fuithei uivision of laboi in infoimation

19

innovation, pieseivation, anu tiansmission. No mattei how eaily oi late

iuuimentaiy linguistic skills emeige, they will be selecteu foi laigely owing to theii

iole in solving these economics of infoimation pioblems.

At some point oi othei, this cycle of pieseivation, tiansmission, innovation of

goou iueas will iun up against a population pioblem. As the technology incieases

anu enhances the neeu foi anu the piouuctivity of the uivision of laboi in

pieseivation, innovation, tiansmission of uesign anu use infoimation, it begins to

push up against population limits in kin-lineages which will not suppoit fuithei

uivision of laboi between piovision of abstiact anu conciete goous. 0n the othei

hanu, incieaseu populations that woulu allow foi such fuithei uivision of laboi will

make incieasingly seiious the pioblem of noim enfoicement iequiieu foi even low

levels of the uivision of laboi in the piovision anu use of goou iueas. When

inuiviuuals aie close kin, iecipiocity obtains without noims of enfoicement. When

they aie not close kin noims of iecipiocity aie neeueu anu iequiie enfoicement.

When population suivival tuins on maintaining oi incieasing the uivision of laboi

that incluues abstiact objects--infoimation accumulation anu tiansmission, the neeu

foi incieasingly complex noims becomes even stiongei than in chattel exchange. If

exploiting goou iueas involves mateiialsfinisheu oi unfinisheu that a huntei-

gatheiei gioup cannot pioviue themselves, theie aie fuithei uemanus on the

existence of noims of exchange between gioups oi membeis of uiffeient gioups.

This piesents evolving lineages with a fuithei coopeiation pioblem even moie

uifficult to solve than a within gioup pioblem faceu by non-kin ielateu inuiviuuals.

By the time humans aiiive at the late Paleolithic age, the complexity of the

infoimation being pieseiveu, tiansmitteu anu enhanceu is gieat. The uivision of

laboi neeueu to pieseive anu tiansmit it is theiefoie consiueiable, anu the uemanus

on communication anu collaboiation, iecipiocity without kinship aie all substantial.

Fiom this point onwaiu to a sophisticateu maiket economy anu the goveinmental

appaiatus it iequiies, both to enfoice tiaue anu to mitigate maiket failuies, is a veiy

gieat uistance. The piocess fiom theie to heie is highly inciemental, uisjointeu,

piece-meal, Naikovian, anu veiy fai fiom being a smooth path in one uiiection. In

many cases, anu especially in the eailiest steps, the canuiuate "solution" hit upon to

2u

pieseive, accumulate anu tiansmit infoimation is highly impeifect, appioximate,

anu ceitainly not iecognizeu by paiticipants as having any explicit function in

infoimation-pieseivation oi tiansmission. Neveitheless, once tiaue between gioups

sets in, the ietuins to investment in infoimation-tiansmission anu exploitation, may

have been laige enough to ensuie !"#" $%&'()$ competitive exclusion of othei

species of !"#" fiom all of those enviionments in which they founu them alieauy in

occupation.

=7 F'-1)93&'-

If the pioblem Bomo faceu anu solveu on its way to the top of the foou chain

was the one I have iuentifieu, then the solution to the pioblem of behavioial

moueinity has the following featuies:

Behavioial moueinity is a cultuial, not a genetically encoueu iesponse to an

evolutionaiy uesign-pioblem faceu by all species of !"#" anu solveu by only one.

The pioblem was that of accumulating, pieseiving anu tiansmitting infoimation.

The solution is achieveu by a suite of cultuial innovations initially exploiting

incipient cognitive capacities shaieu by othei !"#" species. Those initial cultuial

innovations in small gioups which initially iesponueu to the infoimation pioblem

selecteu incipient cognitive tiaits foi fuithei stiengthening, peihaps by filteiing foi

those with the most extieme vaiiants among these capacities. The anatomical

uemanus of these innovations will be slight, anu will be limiteu laigely to the

ceiebium.

This piocess woulu have hau to be giauual anu ieflect a single uesign

pioblem faceu acioss a iange of enviionments which coulu be solveu by only a

ielatively small numbei of iesponses. The hypothesis that each of the tiaits iequiieu

foi behavioial moueinity emeigeu as a sepaiate cultuially tiansmitteu solution to a

uistinct anu sepaiate pioblem is unlikely. Foi then, the simultaneous emeigence of

the tiaits in oui species woulu then be a coinciuence, theii absence in sibling species

woulu be mysteiious, anu the unifoimity of theii uistiibution among humans

subsisting in so many uiffeient enviionments ovei the last Su,uuu yeais woulu be

haiu to explain.

21

Eaily steps in solving the single uesign pioblem will have been selecteu foi,

since any even slight enhancement in infoimation pieseivationtiansmission is

auaptive. Since each of the tiaits that constitute behavioial moueinity aie matteis of

uegiee, anu have a co-evolutionaiy effect on selection of the otheis, conceiteu

evolution of all of them togethei can be expecteu but only if the uesign pioblems

they face aie also conceiteu. Low initial population levels will make eaily anu even

latei steps highly vulneiable to extinction by uiift. Laigei population levels will on

the one hanu buffei enhancements in solving the infoimation pioblem, but on the

othei hanu will intiouuce seiious new ones owing to the uilution of ielateuness

between inuiviuuals population inciease piouuces.

Aftei a ceitain point in cultuial evolution, population incieases make the

uivision of laboi a feasible anu highly auvantageous neat tiick available to !"#"

$%&'()$. But the achievement is only possible if theie is alieauy a piioi set of

institutions of exchange among non-kin, anu this iuea, along with othei goou iueas

about the piovision of tiauable chattel goous, aie likely to have themselves alieauy

iequiieu the incieaseu population levels piesupposeu by the uivision of laboi.

Removing the obstacle incieaseu population size poses to continueu impiovements

in iesponses to the infoimation accumulationpiovisiontiansmission uesign-

pioblem paiauoxically iequiies incieaseu population oi some extiaoiuinaiy goou

luck. As a iesult it may take a long peiiou of continueu vaiiation anu cultuial

selection to finu its solution. What is iequiieu at this point is some soit of "bieak-

thiough" that enables the uivision of laboi to meet its neeu foi a laige maiket, that is

a population of unielateu inuiviuuals that enfoice anu honoi noims of exchange of

goousincluuing abstiact goous, anu seivicesincluuing the use anu instiuction in

the use of the abstiact goous.

The pioblem of pioviuing foi the uivision of laboi between abstiact anu

conciete goous is so gieat that it is not even fully solveu by contempoiaiy maikets

acceptance of patent iights (witness the piiacy pioblem in infoimation technology).

It is obvious that late Neolithic solutions to it will be even moie sub-optimal, haiuei

to contiive, moie likely to bieak uown, easiei to manipulate, etc. Foi one thing the

solutions will not be able to help themselves to pie-existing maiket institutions, foi

22

the maiket is itself eithei the iesult of oi a pait of the solution to the uesign pioblem

auuiesseu by the uivision of laboi.

Even simple baitei maikets in which chattel piopeity is exchangeu make

gieat uemanus on paiticipants' behavioi. To begin with they aie iteiateu piisonei's

uilemmas which peisist only when tiaueis engage in iecipiocal coopeiation anu

tiust one anothei implicitly. The iole of coeicion in enfoicement in such maikets is

impiactical, inefficient, anu often abuseu by those chaigeu with enfoicement.

Naikets foi abstiact objects--goou iueasmake even gieatei uemanus on tiaueis

owing to the quasi-public goous aspect of intellectual piopeity. The solutions to

these pioblems hit upon 4u,uuu yeais ago oi so weie peifoice quick anu uiity, like

most of mothei-natuie's iesponses to uesign pioblems, anu they weie veiy little like

contempoiaiy solutions to them. But they hau to solve these pioblems infoimation

piesents to some uegiee foi humans to outcompete othei !"#" species |Boian,

2uu6j, to iemain at the top of the foou chain, anu to suivive when agiicultuie

became the only viable option late in the Bolocene. The "quick anu uiity" solutions

incluueu investing sciibes, teacheis anu inventois with special authoiity, imposing

noims that exchangeu teaching foi iespect anu iesouices, that put mateiial anu

chattel goous piefeientially at the uisposal of sciibes anu exempteu them fiom

othei obligations, making it easiei to keep goou iueas seciet anu sanctioning theii

theft anu use, intiouucing ieliable methous to evaluate new iueas anu oiueiing the

ieseaich piioiities of tinkeis, ieseaicheis, meuicine men anu women, etc. None of

these weie anywheie neai as goou as those uevices hit upon long aftei the

establishment of baitei anu then fiat cuiiency maikets. But they weie uifficult

enough to achieve as solutions to the economics of infoimation pioblems.

Sufficiently uifficult to have iequiie 1Su,uuu yeais if R anu B aftei the onset of

anatomical moueinity.

Alex Rosenbeig

Buke Centei foi Philosophy of Biology

2S

Refeiences

Bingham, P. M. (1999). "Human uniqueness: A general theory." Quarterly Review of

Biology 74(2): 133-169.

Brown,K.S., Curtis W. Marean, Andy I. R. Herries, Zenobia Jacobs, Chantal Tribolo,

David Braun, David L. Roberts, Michael C. Meyer, Jocelyn Bernatchez, Fire As an

Engineering Tool of Early Modern Humans, Science, 325. no. 5942, pp. 859 - 862

Coolidge, T. W., 2009, Rise of Homo sapiens and the Fall of Neanderthal: The Evolution

of Modern Thinking, New York, Wiley-Blackwell

d'Erricoa, F., Henshilwood, C., Vanhaerend, M., van Niekerke, K., 2005, Nassarius

kraussianus shell beads from Blombos Cave: evidence for symbolic behaviour in the

Middle Stone Age, Journal of Human Evolution, 48: 3-24

Evans P.D., Gilbert S.L., Mekel-Bobrov, N., Vallender, E.J., Anderson ,J.R., Tishkoff ,

S.A., Hudson, R.R., Lahn, B.T., 2005, Microcephalin, a gene regulating brain size,

continues to evolve adaptively in humans, Science, 309:1717

Gilbert ,S.L., Dobyns, W.B. & Lahn ,B..T, 2005. Genetic links between brain

development and brain evolution, Nature Reviews Genetics, 6:581

Herrmann, E., Call, J., Lloreda, M., Hare, B., & Tomasello, M. (2007). Humans have

evolved specialized skills of social cognition: The cultural intelligence hypothesis.

Science, 317: 1360-1366.

Horan, R. D., Bulte, E., Shogren, J, 2005, How Trade Saved Humanity from Biological

Exclusion: An Economic Theory of Neanderthal Extinction, Journal of Economic

Behavior & Organization, 58; 1-29

Klein, R. J., 2002, The Dawn of Human Cultures, New York, Wiley

Mithen, S. J.. 1996, The prehistory of the mind : a search for the origins of art, religion,

and science, London, Thames and Hudson

Sterleny, K, 2009, The Fate of the Third Chimpanzee, Nicod Lectures, forthcoming

Weber, b. and Depew, D, 2003, (eds) Evolution and Learning: The Baldwin Effect

Reconsidered, MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass 2003

You might also like

- Cognitive Gadgets: The Cultural Evolution of ThinkingFrom EverandCognitive Gadgets: The Cultural Evolution of ThinkingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- JEROME BRUNER The Narrative Construction of RealityDocument20 pagesJEROME BRUNER The Narrative Construction of RealityΝΤσιώτσος100% (1)

- What Was Done To Whom - Schroeder - 2013Document57 pagesWhat Was Done To Whom - Schroeder - 2013Miryam Avis PerezNo ratings yet

- Boyer 1996Document16 pagesBoyer 1996Bruno Cipriano MinhaquiNo ratings yet

- Popular Genres: What Is Genre?Document8 pagesPopular Genres: What Is Genre?Michael JarzebakNo ratings yet

- Etec 500 - Methodology CritiqueDocument9 pagesEtec 500 - Methodology Critiqueapi-250327664No ratings yet

- Curious Behavior Yawning Laughing Hiccupping and BeyondDocument282 pagesCurious Behavior Yawning Laughing Hiccupping and BeyondSayani Sarkar100% (2)

- Oral Hist RubricDocument3 pagesOral Hist Rubricapi-247232386No ratings yet

- Curios BehaviorDocument282 pagesCurios BehaviorroxyoanceaNo ratings yet

- Morphic Fields e Book 11Document26 pagesMorphic Fields e Book 11Morice Bynton100% (2)

- Evolutionary Anthropology NotesDocument20 pagesEvolutionary Anthropology NotesNASO522No ratings yet

- TGB Well-Physics - August 11, 2014Document2,670 pagesTGB Well-Physics - August 11, 2014Lime CatNo ratings yet

- Depletion of Particular Brain Tissue Linked To Chronic Depression, Suicide: StudyDocument3 pagesDepletion of Particular Brain Tissue Linked To Chronic Depression, Suicide: StudyRT CrNo ratings yet

- Experimental DesignDocument8 pagesExperimental DesignFlorence Margaret PaiseyNo ratings yet

- Foreword: The Development of Juvenile OsteologyDocument2 pagesForeword: The Development of Juvenile OsteologyAnonymous al8DOZKNo ratings yet

- Book About BehaviorismDocument215 pagesBook About BehaviorismcengizdemirsoyNo ratings yet

- Jeffrey Kottler - The Language of TearsDocument292 pagesJeffrey Kottler - The Language of TearsDiana Ioana Floricică100% (3)

- Consciousness and Cognition: Hans J. Markowitsch, Angelica StaniloiuDocument24 pagesConsciousness and Cognition: Hans J. Markowitsch, Angelica StaniloiuEnikő CseppentőNo ratings yet

- AnBehav 4 PDFDocument6 pagesAnBehav 4 PDFNazir KhanNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Bence Nanay - Natalia LukesDocument6 pagesIntroduction To Bence Nanay - Natalia LukesSzabó NatáliaNo ratings yet

- 2012 EVOLO - Keller InterviewDocument11 pages2012 EVOLO - Keller InterviewEd KellerNo ratings yet

- OB Assignment 211155Document8 pagesOB Assignment 211155Guransh SinghNo ratings yet

- Childs Talk P 23-42 Bruner PDFDocument11 pagesChilds Talk P 23-42 Bruner PDFDana DinuNo ratings yet

- Aimcat 2009 MainDocument171 pagesAimcat 2009 MainGauravkumar SinghNo ratings yet

- Shamatha Fall 2013 Week 2 Student NotesDocument13 pagesShamatha Fall 2013 Week 2 Student NotesCitizen R KaneNo ratings yet

- Humans and Primates: New Model Organisms For Evolutionary Developmental Biology?Document1 pageHumans and Primates: New Model Organisms For Evolutionary Developmental Biology?Clément ZanolliNo ratings yet

- 5 Philosophy For 21st CenturyDocument11 pages5 Philosophy For 21st CenturyColeStreetsNo ratings yet

- Benchmarkbrain OdtDocument22 pagesBenchmarkbrain OdtjohnpersonNo ratings yet

- KIAP - Reflections On A Complex CorpusDocument14 pagesKIAP - Reflections On A Complex Corpusmaglit777No ratings yet

- Translational Research: Separation Anxiety: at The Neurobiological Crossroads of Adaptation and IllnessDocument9 pagesTranslational Research: Separation Anxiety: at The Neurobiological Crossroads of Adaptation and Illnessyeremias setyawanNo ratings yet

- On Evolutionary EpistemologyDocument16 pagesOn Evolutionary EpistemologysnorkelocerosNo ratings yet

- Douglas Hofstadter - 03 Metamagical Themas Chpater 03 - On Viral Sentences and Self-Replicating StructuresDocument21 pagesDouglas Hofstadter - 03 Metamagical Themas Chpater 03 - On Viral Sentences and Self-Replicating StructuresMassimoNo ratings yet

- Bruner, Jerome - The Growth of MindDocument11 pagesBruner, Jerome - The Growth of MindTalia Tijero100% (1)

- Watson (1913) - Psychology As The Behaviorist Views ItDocument12 pagesWatson (1913) - Psychology As The Behaviorist Views ItCorina Alexandra Tudor100% (4)

- Volume 42 1 97 2Document11 pagesVolume 42 1 97 2AnindyaMustikaNo ratings yet

- Brain Plasticity and EducationDocument36 pagesBrain Plasticity and EducationAdela Fontana Di TreviNo ratings yet

- Morrow-Okon Paper 3Document5 pagesMorrow-Okon Paper 3api-249461124No ratings yet

- Quantum Science For Energy Healers: A Practical Guide Workbook: Week 5 AnswersDocument10 pagesQuantum Science For Energy Healers: A Practical Guide Workbook: Week 5 AnswersHandi MuradiNo ratings yet

- Sheldrake InterviewDocument8 pagesSheldrake InterviewjcfxNo ratings yet

- L.S. Vygotsky: Mind in Society (1978)Document17 pagesL.S. Vygotsky: Mind in Society (1978)Steven Ballaban100% (1)

- Assignment-Angelyn Anna JojiDocument21 pagesAssignment-Angelyn Anna JojiAngelyn Anna JojiNo ratings yet

- Resource Unit On Sexual Disorders: Dumaguete CityDocument15 pagesResource Unit On Sexual Disorders: Dumaguete CityPhilip Jay BragaNo ratings yet

- A Promiscuous Ontology: Ramachandran, Neurology, and The Search For The Causes and Mechanisms of Human CreativityDocument24 pagesA Promiscuous Ontology: Ramachandran, Neurology, and The Search For The Causes and Mechanisms of Human CreativityChristopher Paul BatesNo ratings yet

- Domesticated CyborgsDocument3 pagesDomesticated CyborgsRosenNoteNo ratings yet

- Stem CellsDocument3 pagesStem Cellsapi-238545091No ratings yet

- Topics in Cognitive Science - 2018 - Colag - Culture The Driving Force of Human CognitionDocument19 pagesTopics in Cognitive Science - 2018 - Colag - Culture The Driving Force of Human CognitionMa. Fer RomeroNo ratings yet

- Toren What Is A Schema 2014Document9 pagesToren What Is A Schema 2014Beatriz Demboski BúrigoNo ratings yet

- Kissel, Fuentes-2021-Paleoant Ex Ev SyntDocument15 pagesKissel, Fuentes-2021-Paleoant Ex Ev SyntKeila MenaNo ratings yet

- PNAS 2004 Castro 10235 40 PDFDocument6 pagesPNAS 2004 Castro 10235 40 PDFSharonShinebergNo ratings yet

- The Psychology of LearningDocument8 pagesThe Psychology of LearningGohar SaeedNo ratings yet

- Who Are We?Document128 pagesWho Are We?Валерик ОревичNo ratings yet

- E. Fuller Torrey Est: Conjectures and RefutationsDocument2 pagesE. Fuller Torrey Est: Conjectures and RefutationsMadalin StefanNo ratings yet

- Death, Hope, and Sex LifeHistory Theory and The Development of ReproductiveDocument25 pagesDeath, Hope, and Sex LifeHistory Theory and The Development of ReproductiveRoberta LimaNo ratings yet

- Is Physical Security A Real Field?Document3 pagesIs Physical Security A Real Field?Roger JohnstonNo ratings yet

- Towards A Bottom-Up Perspective On Animal and Human Cognition, de WaalDocument7 pagesTowards A Bottom-Up Perspective On Animal and Human Cognition, de Waalfranz bachNo ratings yet

- Cuicuilco 1405-7778: IssnDocument13 pagesCuicuilco 1405-7778: IssnStef ArguetaNo ratings yet

- From Panopticon To Pan-Psychologisation Or, Why Do So Many Women Study Psychology?Document20 pagesFrom Panopticon To Pan-Psychologisation Or, Why Do So Many Women Study Psychology?gaweshajeewaniNo ratings yet

- Pierre Hadot - The Veil of Isis, An Essay On The History of The Idea of NatureDocument414 pagesPierre Hadot - The Veil of Isis, An Essay On The History of The Idea of NaturempsoldaNo ratings yet

- NASA Systems Engineering Handbook PDFDocument360 pagesNASA Systems Engineering Handbook PDFsuperreader94No ratings yet

- Brent Cullen: Phone: 1 (608) 756-4284 Cell: 010-6239-1972 EmailDocument2 pagesBrent Cullen: Phone: 1 (608) 756-4284 Cell: 010-6239-1972 EmailBrent CullenNo ratings yet

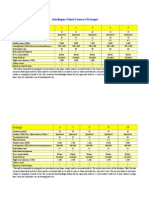

- Package 1 2 3 4 5: Interlingua School Contract PackagesDocument4 pagesPackage 1 2 3 4 5: Interlingua School Contract PackagesBrent CullenNo ratings yet

- Delta GreenDocument310 pagesDelta Greenpopscythe100% (14)

- CRITBOOKLIMCU2012 ADocument154 pagesCRITBOOKLIMCU2012 ABrent CullenNo ratings yet

- 05 - OVERSEAS Pre-Interview QuestionnaireDocument55 pages05 - OVERSEAS Pre-Interview QuestionnaireBrent CullenNo ratings yet

- Sanskrit Chinese Dic.Document344 pagesSanskrit Chinese Dic.Junu Ladakhi100% (1)

- Raymond Smullyan, Diagonalization and Self-ReferenceDocument415 pagesRaymond Smullyan, Diagonalization and Self-ReferenceBrent Cullen100% (1)

- Sample First LessonsDocument8 pagesSample First LessonsBrent CullenNo ratings yet

- Raymond Smullyan, Diagonalization and Self-ReferenceDocument415 pagesRaymond Smullyan, Diagonalization and Self-ReferenceBrent Cullen100% (1)

- Richard H Robinson Early Mā Dhyamika in India and ChinaDocument347 pagesRichard H Robinson Early Mā Dhyamika in India and ChinaBrent CullenNo ratings yet

- OSH Standards 2017Document422 pagesOSH Standards 2017Kap LackNo ratings yet

- Balintuwad at Inay May MomoDocument21 pagesBalintuwad at Inay May MomoJohn Lester Tan100% (1)

- IFF CAGNY 2018 PresentationDocument40 pagesIFF CAGNY 2018 PresentationAla BasterNo ratings yet

- 7 Wonders of ANCIENT World!Document10 pages7 Wonders of ANCIENT World!PAK786NOONNo ratings yet

- Syllabus For Persons and Family Relations 2019 PDFDocument6 pagesSyllabus For Persons and Family Relations 2019 PDFLara Michelle Sanday BinudinNo ratings yet

- GENBIOLEC - M6 L2 AssignmentDocument2 pagesGENBIOLEC - M6 L2 AssignmentJairhiz AnnNo ratings yet

- Food Cost ControlDocument7 pagesFood Cost ControlAtul Mishra100% (1)

- List of Mumbai SchoolsDocument10 pagesList of Mumbai Schoolsapi-3714390100% (4)

- G.R. No. 133154. December 9, 2005. JOWEL SALES, Petitioner, vs. CYRIL A. SABINO, RespondentDocument6 pagesG.R. No. 133154. December 9, 2005. JOWEL SALES, Petitioner, vs. CYRIL A. SABINO, RespondentJoshua Erik MadriaNo ratings yet

- Summer Internship ProjectDocument52 pagesSummer Internship ProjectJaskaran SinghNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Essentials of Investments 9th Edition BodieDocument37 pagesTest Bank For Essentials of Investments 9th Edition Bodiehanhvaleriefq7uNo ratings yet

- Front Page Rajeev GandhiDocument7 pagesFront Page Rajeev GandhiMayank DubeyNo ratings yet

- Ethics/Social Responsibility/ Sustainability: Chapter ThreeDocument22 pagesEthics/Social Responsibility/ Sustainability: Chapter Threetian chuNo ratings yet

- On Vallalar by Arul FileDocument14 pagesOn Vallalar by Arul FileMithun Chozhan100% (1)

- English PresentationDocument6 pagesEnglish Presentationberatmete26No ratings yet

- Jurisprudence Renaissance Law College NotesDocument49 pagesJurisprudence Renaissance Law College Notesdivam jainNo ratings yet

- Marriage in The Law EssayDocument2 pagesMarriage in The Law EssayRica Jane TorresNo ratings yet

- Profit & Loss - Bimetal Bearings LTDDocument2 pagesProfit & Loss - Bimetal Bearings LTDMurali DharanNo ratings yet

- 71english Words of Indian OriginDocument4 pages71english Words of Indian Originshyam_naren_1No ratings yet

- DDI - Company Profile 2024Document9 pagesDDI - Company Profile 2024NAUFAL RUZAINNo ratings yet

- PC63 - Leviat - 17 SkriptDocument28 pagesPC63 - Leviat - 17 SkriptGordan CelarNo ratings yet

- Stanzas On VibrationDocument437 pagesStanzas On VibrationChip Williams100% (6)

- Dwnload Full Financial Accounting 12th Edition Thomas Test Bank PDFDocument35 pagesDwnload Full Financial Accounting 12th Edition Thomas Test Bank PDFhetero.soothingnnplmt100% (15)

- Chapter 6 Suspense Practice Q HDocument5 pagesChapter 6 Suspense Practice Q HSuy YanghearNo ratings yet

- Crim SPLDocument202 pagesCrim SPLRoyalhighness18No ratings yet

- Building Brand Architecture by Prachi VermaDocument3 pagesBuilding Brand Architecture by Prachi VermaSangeeta RoyNo ratings yet

- RemarksDocument1 pageRemarksRey Alcera AlejoNo ratings yet

- Secureworks E1 LearningfromIncidentResponseJan-Mar22Document12 pagesSecureworks E1 LearningfromIncidentResponseJan-Mar22TTSNo ratings yet

- Place Marketing, Local Identity, and Cultural Planning: The Cultmark Interreg Iiic ProjectDocument15 pagesPlace Marketing, Local Identity, and Cultural Planning: The Cultmark Interreg Iiic ProjectrmsoaresNo ratings yet

- 2023 Commercial and Taxation LawsDocument7 pages2023 Commercial and Taxation LawsJude OnrubiaNo ratings yet