Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Alex8 PDF

Uploaded by

Brent CullenOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Alex8 PDF

Uploaded by

Brent CullenCopyright:

Available Formats

SOLVING THE CIRCULARITY PROBLEM FOR FUNCTIONS (A RESPONSE TO NANAY)

Bence Nanay1 describes a circularity problem that the etiological theory of biological functions is said to face.2 The etiological theory of biological functions holds that a token traits function depends on what traits of the relevant type were selected for. The function of a heart is to pump blood only if traits of its type were selected for pumping blood. Circularity sets in if we then classify traits into the relevant typesi.e., the types relevant for the purpose of ascribing functions on the basis of their functions. That is, if a heart is (constitutively) an organ that has the function of pumping blood and if a heart has the function of pumping blood because (constitutively) it is a heart (and hence an organ that has the function of pumping blood) then there is a problem of circularity.3 Nanay also holds that a good theory of functions should meet three desiderata: (1) that a trait be allowed to have more than one function (e.g., feathers can have the function in flight and also the function of thermoregulation), (2) that the function attributions that we make be allowed to depend on our explanatory projects (e.g., if we are interested in how eagles catch mice, we might be more interested in the aerodynamic function of feathers than their function in thermoregulation) and (3) that malfunction be possible, so that a token trait can have the function of performing F even though it cannot perform F (e.g., a broken wing that does not enable flight can nonetheless have the function of enabling flight).

! We agree with these desiderata,4 but they are not exhaustive. Another

"!

desideratum is that the theory gives correct function attributions. It must at least get them approximately right, if it is to be considered in the running. There is room for some revision but not for whole scale revision. Similarly, it is not enough to provide for the possibility of malfunction. Our theory should entail that malfunctioning traits are malfunctioning and that traits that are functioning normally or properly are not malfunctioning. The usual view is that the standards for normal or proper functioning cannot be found by peering at a token trait. Nanay rejects the usual view in order to solve the circularity problem. He suggests that we can avoid this problem by offering an account according to which functions depend on facts pertaining to tokens only. This allows the analysis of functions to remain silent on the individuation of trait types. Here we offer counterexamples to Nanays analysis and more important, show how the etiological analysis solves the circularity problem that it is alleged to face.

I. THE MODAL THEORY On Nanays modal theory, the functions of token traits do not depend on what is true of traits of the type. Instead, they depend on counterfactuals that pertain to trait tokens, regardless of what is true of any other traits of the same type. On Nanays modal theory, performing F is a function of an organisms (Os) trait [token], x, at time t if and only if: 1. There is a relatively close possible world, w, where [token] x is doing F at t. 2. Doing F at t contributes to Os inclusive fitness in w.

! 3. This world, w, is closer to the actual world than any of the possible worlds in which x does F at t but this does not contribute to Os inclusive fitness. Consider how this proposal provides for the possibility of malfunction. An

#!

eagles broken wing is not broken in some relatively close possible world. In that world, other things being equal, the eagle would be able to fly and its ability to fly would contribute to its fitness. Further, a world in which this eagle can fly and flying contributes to its fitness is closer to the actual world than one in which it can fly but this does not contribute to its fitness. So, on Nanays analysis, this particular wing of this individual eagle has the function of flight, even though this eagle cannot fly. Note that, although Nanay leaves the notion of a relatively close world vague, worlds must count as relatively close if the difference to the actual world is no greater than any change required to avert malfunction (or else his theory cannot accommodate actual malfunctions). This, as we will see, is a problem. Like over half of all humans, one of us (A) is lactose intolerant. On Nanays analysis, the mechanisms that make A lactose intolerant (unable to digest lactose as an adult) must have the function of providing lactose tolerance (an ability to digest lactose as an adult). Why is that, and why is it a problem? A little human natural history makes clear why. Long ago in mammalian evolution there was selection for turning off the lactose operon system in adults. It is normal in mammals, including most humans, to begin producing less of the lactase enzyme (needed for digesting lactose) after weaning. Quite recently in human evolution circumstances made it advantageous to change this. It became advantageous to keep the system on, allowing lactase to be produced in adults. This lactase persistence can give adults year round access to food in certain regions (i.e., those with access to domesticated

! milk producing animals or their products). Making it advantageous of course is not the same thing as making it happen. That would be a version of Lamarckian evolution. But owing to improbable events at the level of the nucleotide (ones that happened twice on chromosome 2, first about 7-9,000 years ago and again separately in the last 3000 years, at different nucleotide sites in the region of chromosome 2 in the human genome) the pathway that shuts down lactose digestion in adults was disabled, and the continuing ability to digest lactose was enabled in certain (originally Balkan but later) Nordic populations and certain sub Saharan African ones. Lactase persistence has not yet been driven to fixation. As yet it is present in only a minority of the human population. This succession of events confers on the mechanisms responsible for As lactose

$!

intolerance the function of making him lactose tolerant (i.e., the function of enabling him to digest lactose as an adult) on Nanays theory, for the mechanism satisfies all three of Nanays modal requirements. 1. There is a possible world, w, in which A is able (as an adult) to digest lactose. It is a world in which there was a point mutation in a cell from which A (or one of his ancestors) developed. It is a relatively close world. 2. In w, digesting lactose contributes to As inclusive fitness. 3. World w is closer to the actual world than other worlds in which A digests lactose but this does not contribute to As fitness. Note that if the point mutations occurrence is an event governed by probabilistic laws, then w differs from the actual world, not in any laws, nor in any initial conditions, nor even in its history, up until the indeterministic point mutation that made A lactose tolerant in adulthood in w. So it is a relatively close possible world. The closeness of

! worlds is notoriously hard to measure but this is about as close as possible worlds can get. Certainly, w is closer than a world where A is lactose tolerant in adulthood but

%!

where that is a selectively neutral or a fitness reducing fact about A. For such worlds are ones in which the laws are different or there are more differences in history or in our current environment. Accordingly, if Nanay is right, the function of the mechanisms responsible for As adult lactose intolerance is adult lactose tolerance and the relevant mechanisms in A, in the actual world, are malfunctioning. This is not the right outcome. It is normal for A, given his ethnicity, to have adult lactose intolerance. For every malfunctioning token trait, Nanays theory requires that there be a relatively close possible world in which it is not malfunctioning (e.g., a world in which the eagle did not break its wing). At the same time, for every token trait that is functioning normally (e.g., the shut-down of As lactose tolerance) the modal theory requires that there be no relatively close possible world in which it is improved in some fitness enhancing way (e.g., As lactose operon system does not shut down). The problem is that relatively close with respect to possible worlds remains hopelessly ill defined in Nanays theory and it is hard to see how any more precise definition would help. One can of course deploy it in a circular fashion as follows. If the possible world is just like ours, except that a trait that is actually malfunctioning in our world is functioning properly in that world and all else is otherwise as similar as it can be (consistent with this) then count that world as relatively close. But if the possible world is just like ours, except that a trait that is functioning normally in our world is improved upon in a fitness enhancing way and all else is otherwise as similar as it can be (consistent with this) then count that world as too far away. However, this is circular.

! This is a very general problem for the modal theory. Consider every beneficial mutation that will occur in every species on Earth in the near future (in evolutionary

&!

terms). For each such beneficial mutation, there is something beneficial, F*, that a token trait will one day do, which traits in its lineage are presently unable to do. They can now do F, but not F*. Many of these beneficial things that these future traits will do would be beneficial if done now in the current environment. Many would contribute to fitness if done now. And the possible worlds in which these traits do these beneficial things now are relatively close possible worlds. They are as alike to our world as can be, except for the fact that a beneficial mutation that will actually occur soon will in these worlds have occurred sooner. These worlds are no further away than any world in which a damaging mutation that actually occurs and that actually leads to malfunction does not occur. Moreover, the worlds in which these improved traits do these beneficial things that contribute to fitness is closer to the actual world than any world in which they do these beneficial things and this does not contribute to fitness. On Nanays theory of functions, it follows that many present day traits, which have the function to do F, also have the function to do F*, even though no trait of the type can yet do it. By implication, on his theory, all such traits are malfunctioning by virtue of their current inability to do F*. Further, there is no reason to limit our concern to mutations that will soon occur. Some beneficial mutations that could soon occur will not soon occur, and perhaps will never occur. However, the same in principle problem applies. On Nanays theory, traits malfunction now, by virtue of their inability to do the improved things that would be done were such mutations to occur. The conclusion to draw is that the functions of traits do not depend on distinctive modal facts about token traits alone. More important, the alleged circularity problem that

! motivated this approach is one that the etiological theory can dispose of without difficulty.

'!

2. HOW THE ETIOLOGICAL THEORY SOLVES THE CIRCULARITY PROBLEM

Traits do not need to be typed first, prior to the identification of their functions. Instead, trait individuation and function attributions supervene on the same underlying facts about trait lineages and the selection pressures operating on them. They co-supervene. Traits are located in lineages and a lineage of traits is segmented (or as we say, parsed) both for the purpose of classifying traits and for the purpose of ascribing functions by changes in the selection pressures that have operated on it. No circularity is involved. There is only a superficial appearance of circularity, as we will explain. In what follows, we explain (1) how token traits are located in lineages, (2) how a lineage is then parsed by changes in the selection pressures that operated on it, (3) how the functions of trait tokens are then fixed by their locations in the lineage, and (4) how this resolves the circularity problem. (1) How are token traits located in lineages? The mechanisms and processes that are responsible for inheritance link traits in ancestral and descendent relations and token traits are located within lineages after their ancestors and before their descendants. These are the relations that biologists attempt to trace when they trace relations of homology.5 Suppose, for example, that we are interested in a particular eagles forelimb. Its forelimb (its wing) is located in a lineage of forelimbs, after those of its parents and before those of its offspring, if it has any. This lineage includes ancient fish fins, ancient amphibian legs, and the forelimbs of flightless dinosaurs, as well as the proto-wings of dinosaurs that

! could lift a little above the ground or soar some distance between the trees. More recent are the forelimbs of ancient flying birds, more modern birds, and the wings of ancestral eagles. Our eagles forelimbs are located in this lineage by virtue of their actual history. (2) How is a lineage of traits parsed by changes in the selection pressures

(!

operating on it? Suppose that we are interested in whether a particular eagle forelimb has the function of flight. We locate the relevant lineage of vertebrate forelimbs, the one that evolved into this eagle forelimb. Now we draw imaginary lines in this lineage whenever selection for flight starts or stops. This segments the lineage with respect to selection for flight. (Note that we did not assume that the forelimb had the function of flight in order to do this. We only asked if the forelimb has the function of flight.) If a capacity for flight evolved only once in the lineage leading to the modern eagles forelimbs, and selection for flight did not stop once it started, there is just one line to be drawn in this lineage in this case. (3) How are the functions of token traits fixed? If our question is whether our particular eagle forelimb has the function of flight, first ask to which segment of its lineage (parsed with respect to selection for flight) it belongs. Then ask whether selection for flight operated on ancestral homologs within that lineage. Since the answer is affirmative, the eagles forelimb has the function of flight and it is also therefore a wing (a forelimb that has the function of flight).6 Where lines are to be drawn in lineages will often be subject to a Sorties-like vagueness. A capacity for flight probably evolved gradually and there can be no selection for flight until there is flight.7 But this vagueness is not a problem.8 The vagueness of when in time there was or was not selection for flight corresponds to the vagueness of whether certain ancestral forelimbs did or did not have the function of

! flight. In fact the vagueness of the etiological theory captures the Darwinian gradualism of the phenomena. It is in fact vague when dinosaur forelimbs were first selected for flight and first acquired the function of flight. Note too how well this approach deals with the case of lactase persistence. Well under half of all humans belong to lineages in which there has been selection for lactase persistence. According to the etiological theory, the mechanisms that permit lactose digestion in adulthood in this minority of people have the function of doing so. Why? There was selection for the adult digestion of lactose operating on ancestral mechanisms

)!

in the relevant segments of the lineages to which the mechanisms of this minority belong. Now recall A, who is lactose intolerant. To discern the functions of the mechanism(s) responsible for As lactose intolerance, we need to identify the lineage (or lineages) leading to As mechanism(s). We need to parse it (or them) with respect to selection for the adult digestion of lactose. The relevant mechanisms in A do not belong to segments of a lineage (or segments of lineages) on which selection for the adult digestion of lactose has operated on ancestral mechanisms. So his mechanisms are not malfunctioning in virtue of their inability to provide for the adult digestion of lactose. On our account, one does not need to be in the evolutionary vanguard to function properly; one need not have all of the actually imminent or only possible improvements on our current species design in order to function properly.9 As sketched above, this version of the etiological theory does not say that we must type traits first and then ask what selection recently operated on that type of trait. Instead, it tells us that token traits are located in lineages, which are parsed in accord with stops and starts in selection for F, when it is the function to do F that is at issue. If the

! trait in question belongs to a segment of the lineage in which selection for doing F operated on its ancestors, the token trait has the function to do F. (4) How does this resolve the circularity problem? Function and trait typology

*+!

both depend on past selection history and on changes in selection pressures operating on lineages. Traits are typed in ascribing functions to them, not before ascribing functions to them.10 It is important to stress that, in explaining how a particular forelimb is located in a lineage, in explaining how the lineage is parsed with respect to selection for flight, and in explaining how we determined on that basis if a particular forelimb has the function of flight, we do not assume in advance that the forelimb in question had (or did not have) the function of flight. We do not assume in advance that the eagles wing has the function of flight.11 Rather, we ask if it has the function of flight. Then we parse the relevant lineage at starts and stops in selection for flight and ask if selection for flight had operated on the relevant segment of the lineage, the one to which the token trait in question belongs. We ask whether ancestral traits, within that segment, had been selected for flight. In none of this do we need to know in advance whether the token trait in question had the function of flight. We also do not need to know if it was a wing (or a flipper, or a leg or an arm). We locate it in its lineage and go on from there. There is only a superficial appearance of circularity on the etiological theory. The superficial appearance of circularity derives from the common basis for both trait typology and functions. As Neander has elsewhere remarked, Function ascriptions and these particular kinds of trait classifications go hand-in-hand, hence the superficial appearance of circularity. One cannot get a wife or a husband unless one marries and one cannot get married unless one gets oneself a wife or a husband. But there is no Catch 22 here. We do them both together.12

**!

3. CONCLUSION

The etiological theory meets all of Nanays desiderata. Besides avoiding circularity, he lists three. A token trait can have more than one function, our function attributions depend on our explanatory projects, and there is the possibility of malfunction. A token trait, x, can have more than one function. It can have the functions, F and G. If you are interested in whether a token trait, x, has the function to F, locate x in its lineage. Draw a line in the lineage whenever there is a stop or start in selection for performing F. If there was selection for performing F operating on traits ancestral to x within its segment of the lineage, then x has the function to F. Now, to see if the same trait, x, has the function to G, again locate x in its lineage. But now draw a line in the lineage whenever there is a stop or start in selection for performing G. If there was selection for performing G operating on traits ancestral to x within its segment of the lineage, then x has the function to G. Since there can be selection for both doing F and doing G operating on a lineage of traits at the same time, one and the same trait can have the function to F and to G. The etiological theory also recognizes that function attributions depend on the explanatory project: that is to say that the attributions we make depend on our explanatory projects. We can ask whether x has the function to F, or whether it has the function to G, depending on these explanatory projects. However, the functions themselves are not dependent on our explanatory projects. Whether x has the function to F or to G (or both) depends on history, not on which questions we ask or which questions are relevant to our projects.

*"! The way this version of the etiological theory draws lines in lineages also allows

for the possibility of malfunction. A trait that cannot do F can nonetheless belong to a segment of a lineage of traits in which selection for F-ing operated on traits ancestral to x. A broken wing of an eagle belongs to a segment of a lineage in which selection for flight operated on ancestral forelimbs. The etiological theory of functions is epistemically demanding. Drawing the lines in lineages that it employs requires a lot of phylogenetic information along with a lot of ecological information. But the issue between Nanay and us is metaphysical: what constitutes a function. We have expounded the metaphysical issues in terms of questions that need to be answered so as to show that there is no circularity in the constitutive conditions. We do not imagine that biologists will, in practice, perform these steps each time they attribute a function to a trait, no more than we assume that we always establish the chemical composition of water before we drink it.

KAREN NEANDER Duke University ALEX ROSENBERG Duke University !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! 1 A Modal Theory of Function, THIS JOURNAL, 107 (8): 412-431.

2

Others have also addressed the problem. See for instance, Paul S. Davies, Norms of

Nature (MIT: Cambridge, 2001), Paul Griffiths, In what sense does nothing in biology make sense except in the light of evolution? in Acta Biotheoretica, 57 (2009): 11-32, and Karen Neander, How are traits typed for the purpose of ascribing functions to

*#!

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! them? in Jean Gayon (ed.) La Notion de Fonction: des sciences de la vie a la technologie (2010).

3

Nanay points out that most other theories of function potentially face a similar problem.

They all seem to need an independent function-free way to individuate trait-types or else to abandon the idea that functions belong to tokens in virtue of their types. However, the alternatives to typing traits by their functions do not look promising, or so Nanay argues. For example, if we use homology as the basis for the classification of traits, the resulting classifications are insufficiently fine-grained for many purposes (as we have previously argued ourselves in Rosenberg and Neander, Are Homologies (Selected Effect or Causal Role) Function Free? in Philosophy of Science, 76, 3 (2009): 307-334). Two traits can be homologous and yet can have very different functions and so homology does not seem to provide the fine-grained types needed for ascribing functions to traits. For instance, the forelimbs of vertebrates are all homologous and yet different vertebrate forelimbs have different functions. Some have the function of assisting in flight, some in paddling or swimming, some in grasping the branches of trees, some in walking and running and so on. So it cannot be that we type traits for the purpose of ascribing functions to them on the basis of homologous relations alone. But add function to the mix and one seems to have a problem of circularity. The appearance is deceiving we shall argue.

4

We understand (2) in such a way that biological functions do not depend on our

interests, although the attributions that we make do so depend.

5

There are difficulties in providing a full treatment of historical homology and we do not

slight those difficulties but nor do we treat them here. These difficulties do not include

*$!

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! the present problem of circularity and nor does Nanay seem to take issue with a notion of historical homology.

6

A few other examples might help. Consider a modern penguins forelimb (one of its

flippers) and a modern emus forelimb (one of its vestigial wings). First, locate the lineage of forelimbs for the penguin. Now draw imaginary lines in the lineage whenever selection for flight starts or stops. There is thought to be at least one time when selection for flight starts and at least one time when selection for flight stops. As long as our penguins forelimb belongs to a segment of this lineage in which there was no selection for flight operating on ancestral forelimbs, it does not have the function of flight. Now consider the emus forelimb. Again, we can segment its lineage by drawing lines whenever selection for flight stops or starts. Then we can ask whether this emus forelimb belongs to a segment of the lineage in which ancestral forelimbs were selected for flight. It does not. It belongs to a segment of the lineage in which there was no selection for flight. So it is vestigial with respect to flight.

7

The capacity for flight seems to have developed gradually, either from an enhancement

of an ability to soar from tree to tree in arboreal creatures or from an enhancement of an ability to leap from the ground in ground-dwelling creatures.

8

Vagueness is a problem for the modal theory of functions because, in order to apply the

theory, the vagueness of the notion of relatively close possible worlds must be resolved in an ad hoc way, after peeking at the functions of traits.

9

Although it remains true on our proposal that much relevant selection is recent, relative

to a token trait, this proposal differs from the modern history version of the etiological theory of functions that Nanay considers. In some lineages, traits can gain and lose and

*%!

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! can again gain other functions fast. So it is hard to see how a non-circular answer can be given to the question, How recent is recent enough? On our approach, we do not need to answer that question. If selection for F-ing starts and stops in short order, there might be more than one segment of the lineage vis a vis F that is recent, in evolutionary terms. But this does not matter for whether that trait has the function to perform F on the present proposal. Instead, it matters only which segment the token trait belongs to and whether, within that segment, there was selection for performing F operating on ancestral traits.

10

Nanay touches on something like this strategy (see Nanay, op. cit., note 1, p. 421) but

he fails to see how it solves the circularity problem. This is presumably because Nanay treats any appeal to what there was selection for as an appeal to function. According to the etiological theory of functions, functions are (roughly) what traits were selected for. So Nanay presumably thinks that, if we appeal to what there was selection for in our proposed solution to the problem, we appeal to function and return to running around the same old circle.

11

Nor do we assume in advance that the penguins flipper or the emus vestigial wing did

not have the function of flight. See note 6.

12

This is in the original English, from Neander op. cit., note 2 (p XXX), which offers an

earlier version of this solution to the circularity problem.

You might also like

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Brent Cullen: Phone: 1 (608) 756-4284 Cell: 010-6239-1972 EmailDocument2 pagesBrent Cullen: Phone: 1 (608) 756-4284 Cell: 010-6239-1972 EmailBrent CullenNo ratings yet

- NASA Systems Engineering Handbook PDFDocument360 pagesNASA Systems Engineering Handbook PDFsuperreader94No ratings yet

- Pierre Hadot - The Veil of Isis, An Essay On The History of The Idea of NatureDocument414 pagesPierre Hadot - The Veil of Isis, An Essay On The History of The Idea of NaturempsoldaNo ratings yet

- Delta GreenDocument310 pagesDelta Greenpopscythe100% (14)

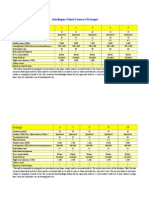

- Package 1 2 3 4 5: Interlingua School Contract PackagesDocument4 pagesPackage 1 2 3 4 5: Interlingua School Contract PackagesBrent CullenNo ratings yet

- 05 - OVERSEAS Pre-Interview QuestionnaireDocument55 pages05 - OVERSEAS Pre-Interview QuestionnaireBrent CullenNo ratings yet

- CRITBOOKLIMCU2012 ADocument154 pagesCRITBOOKLIMCU2012 ABrent CullenNo ratings yet

- Sample First LessonsDocument8 pagesSample First LessonsBrent CullenNo ratings yet

- Raymond Smullyan, Diagonalization and Self-ReferenceDocument415 pagesRaymond Smullyan, Diagonalization and Self-ReferenceBrent Cullen100% (1)

- Sanskrit Chinese Dic.Document344 pagesSanskrit Chinese Dic.Junu Ladakhi100% (1)

- Raymond Smullyan, Diagonalization and Self-ReferenceDocument415 pagesRaymond Smullyan, Diagonalization and Self-ReferenceBrent Cullen100% (1)

- Richard H Robinson Early Mā Dhyamika in India and ChinaDocument347 pagesRichard H Robinson Early Mā Dhyamika in India and ChinaBrent CullenNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- IB Biology Topic 2 CellsDocument119 pagesIB Biology Topic 2 CellsAdrianMiranda100% (1)

- Chlorhexidine GluconateDocument6 pagesChlorhexidine GluconateArief Septiawan TangahuNo ratings yet

- BIOLOGY AssessmemtDocument4 pagesBIOLOGY AssessmemtMei Joy33% (3)

- Bio 1 - 2 QuizDocument2 pagesBio 1 - 2 QuizalexymersNo ratings yet

- Vector DiseaseDocument2 pagesVector DiseasenallurihpNo ratings yet

- Crockett 2014Document14 pagesCrockett 2014JulioRoblesZanelliNo ratings yet

- Physiology ImmunityDocument18 pagesPhysiology ImmunityHamza SultanNo ratings yet

- Acute Glomerulonephritis Case StudyDocument12 pagesAcute Glomerulonephritis Case StudyPrincess Tindugan100% (1)

- AlbuminDocument27 pagesAlbuminSanjay VeerasammyNo ratings yet

- 23 Soft Tissue TumorsDocument115 pages23 Soft Tissue TumorsorliandoNo ratings yet

- CvaDocument170 pagesCvaApril Jumawan ManzanoNo ratings yet

- CCO Metastatic NSCLC SlidesDocument67 pagesCCO Metastatic NSCLC Slidesfedervacho1No ratings yet

- Non-Invasive Prenatal Testing (NIPT)Document13 pagesNon-Invasive Prenatal Testing (NIPT)Andy WijayaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6 VariationDocument12 pagesChapter 6 VariationBro TimeNo ratings yet

- Growth and DevelopmentDocument150 pagesGrowth and Developmentvicson_4No ratings yet

- The Plant RemedyDocument109 pagesThe Plant RemedyJef Baker100% (2)

- Genetics Fruit Fly Summary ReportDocument4 pagesGenetics Fruit Fly Summary Reportneuronerd100% (1)

- EVEROLIMUSDocument2 pagesEVEROLIMUSNathy Pasapera AlbanNo ratings yet

- Lippincotts Illustrated Biochem Review 4th Ed Compiled QuestionsDocument36 pagesLippincotts Illustrated Biochem Review 4th Ed Compiled QuestionsKathleen Tubera0% (1)

- AbnormalitiesDocument17 pagesAbnormalitiesDitta Nur apriantyNo ratings yet

- Comparative Morphology Developmentand Functionof Blood Cellsin Nonmammalian VertebratesDocument12 pagesComparative Morphology Developmentand Functionof Blood Cellsin Nonmammalian VertebratesCarl DumadaogNo ratings yet

- How Can A Nasa Technology Help Someone With Heart Disease?Document14 pagesHow Can A Nasa Technology Help Someone With Heart Disease?Dean EspinosaNo ratings yet

- Solution Manual For Laboratory Manual For Anatomy Physiology Featuring Martini Art Main Version Plus Masteringap With Etext Package 5 e Michael G WoodDocument4 pagesSolution Manual For Laboratory Manual For Anatomy Physiology Featuring Martini Art Main Version Plus Masteringap With Etext Package 5 e Michael G WoodKarenAcevedotkoi100% (40)

- Aneurysmal Bone CystDocument22 pagesAneurysmal Bone CystSebastian MihardjaNo ratings yet

- Tea Polyphenolics and Their Effect On Neurodegenerative Disordersa ReviewDocument10 pagesTea Polyphenolics and Their Effect On Neurodegenerative Disordersa ReviewJenny Rae PastorNo ratings yet

- About Stomach Cancer: Overview and TypesDocument14 pagesAbout Stomach Cancer: Overview and TypesMuhadis AhmadNo ratings yet

- Ob AssessmentDocument7 pagesOb AssessmentAlyssa LippNo ratings yet

- Celiac Disease in ChildrenDocument59 pagesCeliac Disease in Childrend-fbuser-57045067No ratings yet

- Health Hazards of Chemicals Commonly Used On Military BasesDocument35 pagesHealth Hazards of Chemicals Commonly Used On Military Basesmale nurseNo ratings yet

- Bipolar Disorder Fact SheetDocument5 pagesBipolar Disorder Fact SheetDenice Fayne Amid TahiyamNo ratings yet