Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Mycosis Fungoides PDF

Uploaded by

rfbruneiOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Mycosis Fungoides PDF

Uploaded by

rfbruneiCopyright:

Available Formats

Skin Cancers

Successful Treatment of Mycosis Fungoides

a report by

L a w re n c e A M a r k , M D , P h D , FA A D

Assistant Professor of Dermatology, Indiana University School of Medicine, and Service Chief, Dermatology, Wishard Hospital

Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma is a heterogenous group of nonHogkins lymphomasincluding mycosis fungoides (MF), anaplastic large cell lymphoma, adult T-cell lymphoma/leukemia, subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma, and extranodal natural killer (NK)/T-cell lymphoma, nasal typeeach uniquely distinguishable based on clinical presentation, immunohistochemistry, prognosis, and treatment strategies. The classification schema is constantly being revised to accommodate new information as it is gathered on this rare set of diseases; however, it is widely recognized that MF is by far the most prevalent of this group, accounting for approximately 50% of primary cutaneous T-cell lymphomas1 with an incidence of 0.64/100,000 person-years.2 This incidence has been on the rise over the last 30 years, although it is not clear whether this is due to better diagnostic tools (such as polymerase chain reaction [PCR]-based T-cell gene rearrangement technology), heightened awareness among clinicians, or a true rise secondary to an as yet unidentified environmental factor or infectious agent. Nonetheless, it has become a more prominent disease, posing difficult management choices for the clinician, but also drawing clinical research to help tackle this difficulty. New treatment choices are now available that were unheard of 1020 years ago, such as retinoid therapy with bexarotene, histone deacetylase therapy with vorinostat, and monoclonal antibody therapy with alemtuzumab and denileukin diftitox. In this article, I would like to first discuss tenets of therapy in general, but then focus on the treatment options readily manageable by the dermatologist specifically. Tenets of Therapy Clinically Visible Disease Should Be Actively Treated Once the diagnosis of MF has been established, one must determine what the goal of therapy will be: palliation or remission. As MF usually occurs in an aging population that may have numerous other comorbidities leading to limited life expectancy, palliative interventions may be considered for these individuals to avoid unnecessary side effects of more aggressive therapy. A frank and honest discussion with the patient and family regarding the typical indolence of MF and the place of various therapies in this disease will help guide the decision. However, for younger patients or those in general good health, an attempt at achieving remission or near complete remission is recommended. This is because without treatment it is expected that the disease will continue to progress, however slowly or quickly, from the patch stage to involve more skin area, become plaque stage, form tumors, and then involve lymph nodes and/or blood. The exception to this may be Woringer-Kollop disease or pagetoid reticulosis subsets of MF, which by definition are nonprogressive and isolated in skin involvement. As indirect evidence for the

assertion that MF will progress if untreated, one may scrutinize a seminal article from Stanford University reporting the prognoses for the various stages of MF. Their data show that only stage IA disease is associated with no measurable decrease in life expectancy, possibly because all of their patients obtained treatment, even those with early-stage disease in whom treatment may be able to eliminate tumor burden.3 This agrees with the findings of Swanbeck et al., who compared mortality of MF in the pre- and post-psoralen with ultraviolet A therapy (PUVA) eras, a therapy generally considered useful only in stage IAIIA disease, revealing an overall 50% reduction in death rate.4 The logical conclusion is to actively treat clinically identifiable disease when able, thereby halting progression through decreased tumor burden and avoiding increased mortality. Additionally, early-stage disease is more amenable to obtaining sustainable complete remission, whereas this is usually unrealistic in more advanced stages of MF. However, one must remain cognizant that maintenance of remission may require long-term ongoing treatment regimens, which may have cumulative adverse effects in themselves. A frank discussion of risk versus benefit is always required before embarking on long-term therapy for these patients. Specific Therapy Is Based on Stage of Disease Just as the astute oncologist would avoid multi-agent chemotherapy for MF with only a few patches of involvement, so the astute dermatologist would not treat progressive tumor-stage disease with topical nitrogen mustard alone. However, most patients do present with early disease that is amenable to skin-directed therapies that the dermatologist will be able to manage. Table 1 addresses which first-line therapies may be best suited for any particular disease stage and generally expected responses. Obviously, clinician-specific preferences, medication side-effect profiles, patient comorbidities, and disease aggressiveness exhibited by clinical behavior often color the specific choice of therapy. This list is not intended to be comprehensive, nor an edict for correct choices of therapy for any one individual, but merely a guideline to aid clinical practice.

Lawrence A Mark, MD, PhD, FAAD, is an Assistant Professor of Dermatology at the Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis and Service Chief for Dermatology at the local county-funded hospital, Wishard Hospital, and the dermatological arm of the Mel and Bren Simon Cancer Centers Multidisciplinary Melanoma Clinic. Dr Marks research interests are in cutaneous T-cell lymphomas and melanoma. He is a Fellow of the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) and a member of both the Society for Investigative Dermatology (SID) and the Biophysical Society. Dr Mark received his MD, PhD, and residency training at Indiana University School of Medicine. E: lamark@iupui.edu

TOUCH BRIEFINGS 2008

69

Skin Cancers

Table 1: Suggested First-line Therapies Matched to Disease Stage

Stage I. Limited patches to generalized plaques Modality Topical steroid Bexarotene gel Nitrogen mustard ointment Spot radiation Phototherapy Nitrogen mustard ointment Phototherapy Total skin electron beam Bexarotene oral Interferon alfa Denileukin diftitox Gemcitabine Extracorporeal photopheresis Total skin electron beam Bexarotene oral Denileukin diftitox Bexarotene oral Denileukin diftitox Alemtuzumab Traditional single-agent chemotherapy Alternate agent in stage-specific list Vorinostat Traditional single-agent chemotherapy Allogeneic stem-cell transplantation Response Type Palliative, maintenance for non-descript lesions Remittive or palliative Remittive (includes mechlorethamine and bis-chlorethyl nitrosourea) Remittive Remittive Remittive Remittive Remittive, requires encore maintenance therapy Palliative, remittive in conjunction with phototherapy Palliative, remittive in conjunction with phototherapy Palliative Palliative Palliative Remittive, requires encore maintenance therapy Palliative Palliative Palliative Palliative Remittive Methotrexate, gemcitabine, chlorambucil, cyclophosphamide, etoposide, liposomal doxarubacin; all considered palliative with rare remission As above Palliative Methotrexate, gemcitabine, chlorambucil, cyclophosphamide, etoposide, liposomal doxarubacin; all considered palliative with rare remission Remittive

II. Generalized plaques or tumors with dermatopathic nodes

III. Erythroderma

IV. Nodal or visceral involvement

Relapsed/unresponsive disease

Patients in Remission Should Be Followed Up Indefinitely Certainly, those patients with only partial response or palliation require continued follow-up to periodically assess for disease progression. Such progression would weigh heavily on further therapeutic choices and expected prognosis. However, if complete remission has been achieved, what guidelines are there for continued follow-up? This author is currently unaware of any specific evidence-based recommendations such as there are for melanoma or squamous cell carcinoma. While patients are on maintenance therapy for their remission, they are usually seen at least three to four times per year, allowing for relatively close monitoring. What if the patient remains in remission, even after complete cessation of all therapeutic modalities? My practice is to at least see these individuals every three to four months for two years, followed by once every six months for three years and then yearly thereafter, with instructions to return more urgently if they have concern for recurrence. Typically, they have high-potency topical steroids on hand, and should raise concern if there is a rash that persists despite four to six weeks of medication applications. For practical purposes, the definition of cure as being free of disease for eight years after all therapy has ended worked in a nitrogen mustard trial5 and has been suggested by Peter Heald as a standardizable definition to uphold.6 Again, without evidence-based medicine to guide, other than standard of care for non-Hogkins lymphomas as described by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines,7 I see these individuals once yearly indefinitely. Particular therapies that the dermatologist should be expected to manage are any skin-applied, skin-directed, or oral therapies available for this disease. When special equipment is needed (such as for light therapy, total skin electron beam, and extracorporeal photopheresis) or infusional therapies are required,

referral to the oncologist or specialized medical center may be indicated. Nonetheless, most dermatologists feel comfortable with directing light therapy, especially if their practice maintains the light box. Therefore, the following successful therapeutic modalities will be briefly discussed: topical steroid, bexarotene gel, nitrogen mustard ointment, phototherapy, bexarotene oral capsules, interferon alfa (INF-) injections, methotrexate, and vorinostat. For a more complete discussion, please refer to Heald et al.8 High-potency topical steroids are typically used as adjunctive therapies in MF owing to their anti-inflammatory and lymphocytic pro-apoptotic characteristics. It is considered palliative as monotherapy due to the short times before recurrence of disease on discontinuation. However, complete responses to clobetasol applied twice daily for two to three months were seen in 63% of limited early-stage disease.9 Aggressive use of a class I steroid on any suspicious eruption that could represent early relapse, including contact dermatitis and insect bites, may help maintain remission and differentiate between benign dermatitis and malignant disease. Should lesions persist for more than four to six weeks in this scenario, histological evaluation is recommended. Bexarotene 1% gel (Targretin) is typically used for <15% body surface area due to its ability to cause retinoid-induced irritant dermatitis.10 Patients are instructed to begin applying the medication once nightly for one week, followed by twice daily for one week, and then finally thrice daily thereafter for a total of three months. If tolerated, four-times-a-day application is best as there is dose responsiveness to the medication. Irritant response is managed by either decreasing the frequency of application or, better still, by adding daily applications of topical corticosteroid. Once the course has been completed, the patient is allowed to rest for one month to allow for the retinoid dermatitis to

70

US DERMATOLOGY

Successful Treatment of Mycosis Fungoides

resolve and then reassessed for disease burden (cycle 1). If objective response is obtained, another cycle of therapy may be considered. As a retinoid, there should be no cumulative toxicity with regard to cutaneous carcinogenesis or structural damage. In fact, the retinoids typically have activities that counter mutagenic effects. The drug is not absorbed to any significant level, so no blood monitoring is required. Topical alkylating agents are available in two varieties for MF treatment: mechlorethamine (nitrogen mustard) (Mustargen) and bis-chloroethyl nitrosourea (BCNU) (BiCNU, Carmustine). Both are best when compounded into ointment form for delivery because the solution forms are more prone to allow development of contact sensitization, the alcohol in the vehicle has no emollient property, and the product is labile in solution at room temperature. Each compound has a similar risk of causing post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation, erythema, telangectasias, skin tenderness, and burning sensations apart from the contact hypersensitivity reactions. Ten or 20mg% mechlorethamine ointment is applied topically from chin to toes, with sparing application for intertriginous folds once daily in the induction phase. This is performed for up to three or four months to adequately assess for response. One should expect a 6090% complete remission rate with this therapy on early-stage disease.5,11 Once remission is obtained, a maintenance regimen is recommended, but no specific regimen has been studied. One recommendation could be to taper application frequency over several weeks down to at least once weekly, as long as no recurrence is found. Mechlorethamine applications are often used as an encore to maintain remission after radiotherapy. Unfortunately, non-melanoma skin cancer is a known long-term side effect of chronic application, even in the absence of pre-existing photodamage.12,13 Twenty or 40mg% BCNU ointment is applied topically as spot treatment for less than 15% body surface area at a time. This is performed for three to four months to adequately assess for response. One should expect a 6085% complete response rate with this therapy on earlystage disease.14 Maintenance regimens have not been studied and most practitioners repeat cycles of treatment as needed. Only a limited skin area can be treated at any one time due to percutaneous absorption of BCNU leading to bone marrow suppression (thrombocytopenia and lymphopenia). Therefore, it is recommended that blood counts be obtained every other week while on therapy and for one month post-therapy. The risk seems greatest if daily application exceeds 25mg.15 Secondary cutaneous malignancies have not been reported with BCNU. Phototherapy may be delivered as broad-band ultraviolet B (BB-UVB), narrow- band ultraviolet B (NB-UVB), ultraviolet A (UVA), or photochemotherapy using PUVA. There is dose responsiveness to the therapy and most regimens use at least three-times-a-week dosing in the induction phase. Initial dose is limited by Fitzpatrick skin type, but incremental dose increases are given as therapy continues. For a detailed discussion of how to deliver phototherapy safely and effectively, refer to the work by Zanolli and Feldman.16 In general, at least 2030 doses need to be delivered before being able to adequately assess for efficacy. If a response is obtained, dosing is continued until complete clearance is obtained (usually 5060 treatments). Expect to reliably obtain remission of early-stage disease with PUVA therapy.17,18 If complete response is not obtained, the addition of adjuvant therapy with an oral retinoid (such as bexarotene) or subcutaneous INF injections can be quite efficacious. Once remission is obtained, the maintenance phase is obtained by slowly tapering dose frequency to the

most infrequent that maintains long-term remission. This ends up being about once every other week for UVB and as little as once a month for PUVA. If remission has been retained for five years, cessation of therapy may be considered. UVB phototherapy is best suited for patients with thin lesions (patches), owing to the fact that UVB penetrates much less deeply than UVA wavelengths. However, home phototherapy with UVB appeals to many patients due to not having to take an oral pill and convenience, particularly if they live more than half an hour from a phototherapy center. Light therapy has cumulative risks for non-melanoma and melanoma skin cancers. It is recommended that the total number of UVA treatments not exceed 250 over a lifetime to reduce this risk. Other risks include photosensitivity, phototoxicity, cataract formation, and hyperpigmentation. Furthermore, psoralen exacerbates the risk for phototoxicity and adds a risk for nausea and vomiting, particularly if doses greater than 30 or 40mg per session are used. Nonetheless, PUVA is considered more efficacious, especially for plaque-stage disease.19,20 Sites of sanctuary from light often occur in intertriginous zones, in skin folds, and on the eyelids. Adjunctive therapy with localized bexarotene gel, BCNU, imiquimod 5% cream, or radiation therapy can be effective for achieving complete remission. Bexarotene (Targretin) oral therapy is available in 75mg tablets and initially dosed at 300mg/m2/day. It is generally well tolerated but does lead to central hypothyroidism, hypercholesterolemia, and hyperlipidemia that must be monitored and controlled with concomitant medications. Other side effects may include headache, hepatitis, pancreatitis (with uncontrolled hyperlipidemia), neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia. Often dose reduction is necessary to avoid these effects, but is to be discouraged if possible as MF is dose-responsive to this medication. Expectations are for response rates ranging from 30 to 60% depending on disease stage. This therapy is considered palliative as disease rapidly returns when the medication is discontinued and median response times are about 18 months before relapse.21,22 In combination with INF and/or phototherapy, it can be a component of a remittive regimen.23,24 Combination therapy is advantageous in that bexarotene may be used at lower doses, reducing the risk for systemic toxicity. In order to safely and effectively deliver the medication, the following recommendations have been proposed: Before starting a patient on oral bexarotene, obtain a baseline fasting lipid panel, liver function test, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), free thyroxine (T4), pregnancy test, and complete blood count (CBC). Screen for comorbid conditions that may interfere with therapy (obesity, diabetes, alcoholism, and estrogen and thiazide use). Provide information on diet and exercise. Pregnancy is an absolute contraindication to therapy with bexarotene. Start a fibric acid derivative, fenofibrate (Tricor) 200mg daily, for one week prior to instituting bexarotene capsules. Gemfibrozil (Lopid) is not recommended as it increases bexarotene levels. If the lipid panel is abnormal, start an HMG Co-A reductase inhibitor, atorvastatin (Lipitor) 20mg once daily for one week, prior to instituting bexarotene capsules. Be aware that combination therapy with fenofibrate and atorvastatin increases the risk for rhabdomyolysis, myopathy, and acute renal failure; therefore, additional monitoring of creatine kinase (CPK) and symptoms is required.

US DERMATOLOGY

71

Skin Cancers

Optimize thyroid function with levothyroxine for at least one week prior to instituting bexarotene capsules. Monitor fasting lipid panel, liver function test, CPK (if needed), T4, and a CBC every two weeks until on a stable dose with no further concomitant medication changes required. Note that TSH need not be further tested as this will reliably go to zero on bexarotene oral therapy. Once stable, monitoring labs may be reduced to once every three months. INF- (Roferon-A, Intron-A) is self-administered by the patient as a subcutaneous injection of three to 18 million units three times per week. Starting with three million units per dose for three months is recommended, and if there is minimal or no response, the dose may be increased as tolerated. When the patient clears or is at maximal response, the dose should be maintained for three additional months and then slowly tapered over 12 months either by frequency of administration or by dose. Expected partial response varies from 30 to 75%, but there is rarely a complete response.2528 Acute side effects include flu-like symptoms of malaise, myalgia, headache, and fever. Bedtime dosing and pre-treatment with acetaminophen help reduce these side effects, but most patients note diminishment of these symptoms after four to six weeks of therapy. Unfortunately, chronic toxicity includes neuropathy, depression, chronic fatigue, and hypothyroidism. Side effects are doserelated and reversible. Laboratory studies should be directed at monitoring for abnormalities of leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, anemia, proteinuria, transaminitis, and hypothyroidism. Methotrexate is delivered either orally or subcutaneously in doses ranging from 5 to 50mg once weekly. Patients with early-stage disease can be expected to have overall response rates of 33% and should occur within six to 12 weeks of

instituting therapy.29 Toxicities include nausea, gastritis, leukopenia, hepatitis, mucositis, and pneumonitis. Therefore, baseline CBC, urinalysis, basic metabolic profile, liver panel, and viral hepatitis screening is recommended. A frank discussion regarding avoidance of pregnancy, alcohol, sulfa-based antibiotic and chronic non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs use is warranted. Suggested monitoring includes CBC and liver function tests at one, two, and four weeks after initiation of therapy. If no abnormalities occur, less frequent monitoring of at least once every three months is recommended. Vorinostat affects gene expression by inhibiting histone deacetylase, but how this mechanism translates into clinical efficacy in MF is still largely unknown. It is administered as monotherapy at 400mg per day with decreased efficacy at lower doses. Partial response rates in the pivotal trial were around 30%, with palliation of pruritus as a notable aspect of vorinostat therapy. The most common side effects include thrombocytopenia, dehydration, and diarrhea; therefore, blood monitoring, pushing oral fluids, and symptomatic use of loperamide are required. The median time to response is 12 weeks.30 In summary, there is an exciting list of therapies, some old and some new, with which the dermatologist can readily treat their MF patients. Expect more oral formulations to be on the way in the near future, as this appears to be where the greatest thrust of current pharmaceutical research lies. Although the array of choices may seem daunting at first, once the goal of therapy has been definedremission or palliationthe choices become clearer. Additionally, limiting therapeutic choices to those appropriate for the patients current stage of disease eases the decision-making process. With common sense and knowledge of the therapy being administered, the dermatologist can effectively and safely treat their ward. As with other cutaneous malignancies, the dermatologist is best suited not only to treat, but also to perform long-term follow-up, once the patient is in remission.

Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al., WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas, Blood , 2005;105:376885. 2. Criscione VD, Weinstock MA, Incidence of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma in the United States, 19732002, Arch Dermatol , 2007; 143:8549. 3. Kim YH, Liu HL, Mraz-Gernhard S, et al., Long-term outcome of 525 patients with mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome: clinical prognostic factors and risk for disease progression, Arch Dermatol , 2003;139:85766. 4. Swanbeck G, Roupe G, Sandstrom MH, Indications of a considerable decrease in the death rate in mycosis fungoides by PUVA treatment, Acta Dermato-Venereologica , 1994;74:4656. 5. Vonderheid EC, Tan ET, Cantor AF, et al., Long term efficacy, curative potential, and carcinogenicity of topical mechlorethamine chemotherapy in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, J Am Acad Dermatol , 1989;20:41628. 6. Heald PW, Memorials and Mandates for Cutaneous Lymphomas, Arch Dermatol , 2003;139:9268. 7. National Cancer Center Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Non-Hodgkins Lymphomas (V.3.2008). Available at: www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/ nhl.pdf 8. Heald PW, Latkowski JA, Wilson LD, Mark LA, Successful therapy of cutaneous T cell lymphoma, Exp Rev Dermatol , 2008;3:99110. 9. Zackheim HS, Kashani-Sabet M, Amin S, Topical corticosteroids for mycosis fungoides. Experience in 79 patients, Arch Dermatol , 1998;134:94954. 10. Heald P, Mehlmauer M, Martin AG, et al., Topical bexarotene therapy for patients with refractory or persistent early-stage cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: results of the phase III clinical trial, J Am Acad Dermatol , 2003;49:80115. 11. Vonderheid EC, Van Scott EJ, Wallner PE, et al., A 10 year

1.

12.

13. 14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

experience with topical mechlorethamine for mycosis fungoides: comparison with patients treated by total-skin electron-beam radiation therapy, Cancer Treat Rep , 1979;63:6819. Lee LA, Fritz KA, Golitz L, et al., Second cutaneous malignancies in patients with mycosis fungoides treated with topical nitrogen mustard, J Am Acad Dermatol , 1982;7:59098. Price NM, Hoppe RT, Deneau G, Ointment based mechlorethamine treatment for mycosis fungoides, Cancer , 1983;52:221419. Zackheim HS, Epstein EH, Crain WR, Topical carmustine (BCNU) for cutaneous T cell lymphoma: A 15-year experience in 143 patients, J Am Acad Dermatol , 1990;22:80210. Zackheim HS, Epstein E, McNutt NA, et al., Topical carmustine for mycosis fungoides and related disorders: A 10 year experience, J Am Acad Dermatol , 1983;9:36372. Zanolli MD, Feldman SR, Phototherapy Treatment Protocols for Psoriasis and other Phototherapy-responsive Dermatoses, Second Edition , Pearl River, NY: The Parthenon Publishing Group, 2000. Diederen PV, Van Weelden H, Sanders CJ, Van Vloten WA, Narrowband UVB and psoralen-UVA in the treatment of early stage mycosis fungoides: a retrospective study, J Am Acad Dermatol , 2003;48:21519. Herrmann JJ, Roenigk HH Jr, Hurria A, et al., Treatment of mycosis fungoides with photochemotherapy (PUVA): long-term follow-up, J Am Acad Dermatol , 1995;33:23442. Ramsay DL, Lish KM, Yalowitz CB, Soter NA, Ultraviolet-B phototherapy for early-stage cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, Arch Dermatol , 1992;128:9313. Hofer A, Cerroni L, Kerl H, Wolf P, Narrowband (311-nm) UV-B therapy for small plaque parapsoriasis and early-stage mycosis fungoides, Arch Dermatol , 1999;135:137780. Duvic M, Hymes K, Heald P, et al., Bexarotene is effective and safe for treatment of refractory advanced-stage cutaneous T-cell

22.

23.

24. 25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

lymphoma: multinational Phase II-III trial results, J Clin Oncol , 2001;19:245671. Duvic M, Martin AG, Kim Y, et al., Phase 23 clinical trial of oral Targretin (bexarotene) capsules for the treatment of refractory or persistent early stage cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, Arch Dermatol , 2001;137:58193. McGinnis KS, Junkins-Hopkins JM, Crawford G, et al., Low-dose bexarotene in combination with low-does interferon alfa in the treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: clinical synergism and possible immunologic mechanisms, J Am Acad Dermatol , 2004; 50:3759. Talpur R, Duvic M, Treatment of mycosis fungoides with denileukin diftitox and oral bexarotene, Clin Lymph Myel , 2006;6:48892. Bunn PA, Foon KA, Ihde DC, et al., Recombinant leukocyte A interferon: An active agent in advanced cutaneous T-cell lymphomas, Ann Intern Med , 1984;101:4847. Dreno B, Godefroy WY, Fleischmann M, et al., Low-dose recombinant interferon-alpha in the treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, Br J Dermatol , 1989;121:5434. Kohn EC, Steis RG, Sausville EA, et al., Phase II trial of intermittent high-dose recombinant interferon alfa-2a in mycosis fungoides and the Sezary syndrome, J Clin Oncol , 1990;8:15560. Olsen EA, Rosen ST, Vollmer RT, et al., Interferon alfa-2A in the treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphomas, J Am Acad Dermatol , 1989;23:395407. Zackheim HS, Kashani-Sabet M, McMillan A, Low-dose methotrexate to treat mycosis fungoides: a retrospective study in 69 patients, J Am Acad Dermatol , 2003;49:8738. Duvic M, Talpur R, Ni X, et al., Phase 2 trial of oral vorinostat for refractory cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, Blood , 2007;109:319.

72

US DERMATOLOGY

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Counselor ManualDocument72 pagesCounselor ManualrfbruneiNo ratings yet

- Billy and Maria Learn About Tornado Safety: Series: 95-04Document13 pagesBilly and Maria Learn About Tornado Safety: Series: 95-04rfbruneiNo ratings yet

- Call To ActionDocument28 pagesCall To ActionrfbruneiNo ratings yet

- Billy and Maria Visit The National Weather Service: Series: 95-01Document12 pagesBilly and Maria Visit The National Weather Service: Series: 95-01rfbruneiNo ratings yet

- EPA Brochure: Before You Go To The BeachDocument2 pagesEPA Brochure: Before You Go To The BeachrfbruneiNo ratings yet

- Billy and Maria Learn About Tornado Safety: Series: 95-03Document13 pagesBilly and Maria Learn About Tornado Safety: Series: 95-03Oana AlexinschiNo ratings yet

- Seasonal Flu: Each Year in The U.S., The Flu Causes More Than 226,000 Hospitalizations and About 36,000 DeathsDocument2 pagesSeasonal Flu: Each Year in The U.S., The Flu Causes More Than 226,000 Hospitalizations and About 36,000 DeathsrfbruneiNo ratings yet

- Treatment Options For Kidney FailureDocument2 pagesTreatment Options For Kidney Failurequelle69No ratings yet

- Facilitator GuideDocument156 pagesFacilitator GuiderfbruneiNo ratings yet

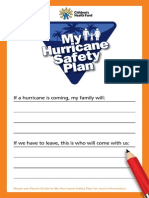

- Family Hurricane Safety Plan Parent GuideDocument2 pagesFamily Hurricane Safety Plan Parent GuiderfbruneiNo ratings yet

- Family Hurricane Plan Childs ChecklistDocument2 pagesFamily Hurricane Plan Childs ChecklistrfbruneiNo ratings yet

- Vascular Access: Preparing For HemodialysisDocument3 pagesVascular Access: Preparing For HemodialysisrfbruneiNo ratings yet

- Vascular Access: Preparing For HemodialysisDocument3 pagesVascular Access: Preparing For HemodialysisrfbruneiNo ratings yet

- SHARP PCI Humidifiers Product BrochureDocument8 pagesSHARP PCI Humidifiers Product BrochurerfbruneiNo ratings yet

- UCM182083Document20 pagesUCM182083rfbruneiNo ratings yet

- TWC April 2012Document7 pagesTWC April 2012rfbruneiNo ratings yet

- Fs8 Flu FactsheetDocument2 pagesFs8 Flu FactsheetrfbruneiNo ratings yet

- Fetal Development Chart: An Alcohol-Free Pregnancy Is The Best Choice For Your BabyDocument2 pagesFetal Development Chart: An Alcohol-Free Pregnancy Is The Best Choice For Your BabyrfbruneiNo ratings yet

- Fasd Poster Pregnancy and Alcohol Don T MixDocument1 pageFasd Poster Pregnancy and Alcohol Don T MixrfbruneiNo ratings yet

- UCM338926Document28 pagesUCM338926rfbruneiNo ratings yet

- Fs8 Flu FactsheetDocument2 pagesFs8 Flu FactsheetrfbruneiNo ratings yet

- Flu Symptoms: When To Seek Medical CareDocument2 pagesFlu Symptoms: When To Seek Medical CarerfbruneiNo ratings yet

- Flu Symptoms: When To Seek Medical CareDocument2 pagesFlu Symptoms: When To Seek Medical CarerfbruneiNo ratings yet

- OTC Dosage InfographicDocument1 pageOTC Dosage InfographicrfbruneiNo ratings yet

- High Blood Pressure: Medicines To Help YouDocument24 pagesHigh Blood Pressure: Medicines To Help YourfbruneiNo ratings yet

- Self Care DayDocument1 pageSelf Care DayrfbruneiNo ratings yet

- KRT Treatmentoptions TransplantDocument3 pagesKRT Treatmentoptions TransplantrfbruneiNo ratings yet

- Women She AltDocument12 pagesWomen She AltrfbruneiNo ratings yet

- OTC Dosage InfographicDocument1 pageOTC Dosage InfographicrfbruneiNo ratings yet

- High Blood Pressure: Medicines To Help YouDocument24 pagesHigh Blood Pressure: Medicines To Help YourfbruneiNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- CVA StrokeDocument6 pagesCVA StrokeMcrstna Lim SorianoNo ratings yet

- Dangers of HerbalifeDocument7 pagesDangers of Herbalifevksingh868675% (4)

- Organization and Management at State and District Level (GUJARAT)Document26 pagesOrganization and Management at State and District Level (GUJARAT)Akriti LohiaNo ratings yet

- A Combined Patient and Provider Intervention For Management of Osteoarthritis in VeteransDocument13 pagesA Combined Patient and Provider Intervention For Management of Osteoarthritis in VeteransHarshoi KrishannaNo ratings yet

- Drug Treatment of AnemiasDocument29 pagesDrug Treatment of AnemiasKashmalaNo ratings yet

- Acute HepatitisDocument14 pagesAcute Hepatitisapi-379370435100% (1)

- Aravind Eye Care Systems: Providing Total Eye Care To The Rural PopulationDocument13 pagesAravind Eye Care Systems: Providing Total Eye Care To The Rural PopulationAvik BorahNo ratings yet

- Gear Oil 85W-140: Safety Data SheetDocument7 pagesGear Oil 85W-140: Safety Data SheetsaadNo ratings yet

- Insulin For Glycaemic Control in Acute Ischaemic Stroke (Review)Document46 pagesInsulin For Glycaemic Control in Acute Ischaemic Stroke (Review)Talitha PuspaNo ratings yet

- Lecture in Geriatrics Physical Therapy 1Document27 pagesLecture in Geriatrics Physical Therapy 1S.ANo ratings yet

- ProQual Fees Schedule June 2021Document19 pagesProQual Fees Schedule June 2021Sohail SNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Health Psychology Biopsychosocial Interactions 9th Edition Edward P Sarafino Timothy W SmithDocument37 pagesTest Bank For Health Psychology Biopsychosocial Interactions 9th Edition Edward P Sarafino Timothy W Smithsequelundam6h17s100% (13)

- Response To States 4.2 Motion in Limine Character of VictimDocument10 pagesResponse To States 4.2 Motion in Limine Character of VictimLaw of Self DefenseNo ratings yet

- Globocan 2020Document2 pagesGlobocan 2020Dicky keyNo ratings yet

- Nutritional Knowledge Among Malaysian ElderlyDocument12 pagesNutritional Knowledge Among Malaysian ElderlyNoor Khairul AzwanNo ratings yet

- IMCI Chart BookletDocument66 pagesIMCI Chart Bookletnorwin_033875No ratings yet

- EVOLUTION OF MODELS OF DISABILITY Notes OnlyDocument1 pageEVOLUTION OF MODELS OF DISABILITY Notes OnlyLife HacksNo ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of Information System in Divine Mercy Hospitalsan Pedro LagunaDocument22 pagesThe Effectiveness of Information System in Divine Mercy Hospitalsan Pedro LagunamartNo ratings yet

- RLE-level-2-packet-week-12-requirement (SANAANI, NUR-FATIMA, M.)Document26 pagesRLE-level-2-packet-week-12-requirement (SANAANI, NUR-FATIMA, M.)Nur SanaaniNo ratings yet

- Presentation 1Document16 pagesPresentation 1Azhari AhmadNo ratings yet

- Peran Perawat KomDocument27 pagesPeran Perawat Komwahyu febriantoNo ratings yet

- IJHPM - Volume 7 - Issue 12 - Pages 1073-1084 Complex LeadershipDocument12 pagesIJHPM - Volume 7 - Issue 12 - Pages 1073-1084 Complex Leadershipkristina dewiNo ratings yet

- Components of Fitness, PARQ and TestingDocument29 pagesComponents of Fitness, PARQ and TestingLynNo ratings yet

- Urtikaria Pada Perempuan Usia 39 Tahun: Laporan Kasus: Moh. Wahid Agung, Diany Nurdin, M. SabirDocument5 pagesUrtikaria Pada Perempuan Usia 39 Tahun: Laporan Kasus: Moh. Wahid Agung, Diany Nurdin, M. SabirZakia AjaNo ratings yet

- 50 Item Psychiatric Nursing Exam IDocument11 pages50 Item Psychiatric Nursing Exam Iɹǝʍdןnos98% (40)

- g8 Health q3 LM Disease 130908005904 PDFDocument64 pagesg8 Health q3 LM Disease 130908005904 PDFkenneth cannillNo ratings yet

- Smart and Sustainable Built Environment: Article InformationDocument14 pagesSmart and Sustainable Built Environment: Article Informationmikky jayNo ratings yet

- 2021 IWBF Classification Rules Version 202110 1Document108 pages2021 IWBF Classification Rules Version 202110 1Sebastian Alfaro AlarconNo ratings yet

- Set C QP Eng Xii 23-24Document11 pagesSet C QP Eng Xii 23-24mafiajack21No ratings yet

- Uti StudiesDocument10 pagesUti Studiesapi-302840362No ratings yet