Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Motivational Theory PDF

Uploaded by

minchanmonOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Motivational Theory PDF

Uploaded by

minchanmonCopyright:

Available Formats

MOTIVATIONAL THEORY AND THE MIDDLE SCHOOL

By J. Douglas Penn

As Prepared for GEAR UP (Gaining Early Awareness and Readiness for Undergraduate Programs) Western Michigan University April 2002

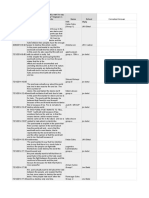

CONTENTS: Motivational Theory and the Middle School Contemporary Research on the Human Brain Achievement Motivation Theory Self-Worth Theory: Motives as the Protection of Personal Worth Differential Teacher Expectations Goal Orientation Theory Attribution Theory Self-Determination Theory Models for Classroom Reform - SCORE Rethinking Motivation School Leadership and Student Motivation Conclusion References 2 5 7 8 10 15 17 18 19 23 25 27 30 31

MOTIVATIONAL THEORY AND THE MIDDLE SCHOOL Few educators would argue with the premise that student motivation is an important influence on learning. Motivation is of particular importance for those who work with young adolescents. (Anderman & Midgley, 1998) Considerable research has shown a decline in motivation and performance for many children as they move from elementary school into middle school (Eccles & Midgley, 1989). Often it has been assumed that this decline is largely caused by physiological and psychological changes associated with puberty and, therefore, is somewhat inevitable. This assumption has been challenged, however, by research that demonstrates that the nature of motivational change on entry to middle school depends on characteristics of the learning environment in which students find themselves (Midgley, 1993). Although it is difficult to prescribe a one size fits all approach to motivating students, research suggests that some general patterns do appear to hold true for a wide range of students. Statistics show that many students, in particular a disproportionate number of African American students, are not succeeding in American schools today (Haynes & Comer, 1990: Knapp, Shields, & Turnbull, 1992). Why is this? Many scholars in the field of motivation place a large part of the blame on what they term, negative motivation. Negative motivation includes student indifference and unpreparedness, which are often motivated behaviors, active attempts to salvage a sense of worth when the likelihood of failure is overwhelming (Brophy, 1983; Covington, 1984, 1992; Dweck & Pempechat, 1983; Rosenholtz & Simpson, 1984; Stipek, 1984). Many youngsters are already motivated, indeed, over-motivated, but their motivation is based on the need to protect their academic self-worth rather than on an interest in learning. Negative motivation and protection of academic self-worth relate directly to lower performance in schools. There are some educators who claim that inner-city African American children do poorly in school because of an identity crisis caused by racial discrimination and consistent use of Euro-centric curriculum in American schools (Cummins, 1986; Ogbu & Matute- Bianchi, 1986) According to this way of thinking, both sets of circumstances have disempowered African American children, lowering their

sense of academic self-worth and resulting in lower achievement (Teel, 1998). Think of a child that enters the main stream classroom for the very first time, wondering, Who am I? For an African American child, the only reference to anyone that looks and acts like them would be Martin Luther King and slavery. For the first four years of this youths educational process all he/she will learn is that they are the descendents of slaves, and before MLK came they still werent free (treated like less than human). This has a cyclical effect because how can they salvage their identities at home by their parent/s who have only been taught the same things by our schools? (Collins, 2002) This in mind, it is only natural that this youth and/or their family members develop adversarial beliefs and behaviors toward the whole schooling process. Now lets take another scenario a young white student comes to school, and for what ever reasons, doesnt have a sense of who he/she is. This child enters the classroom seeing pictures on the walls of various people that look and act like them. All of their storybooks have references of people who look and act like them as heroes and heroines. Everything that they learn about where they came from (history) is positive and they see people who look and act like them only in superior and powerful depictions. This educational process too is cyclical to the point that this youth may take on delusions of grandeur and steer them into racist beliefs. When white children are denied the richness of music, literature, lifestyles, values, and perspectives of other ethnic groups, their potential understandings are limited. Additionally, such an approach (intentionally or unintentionally) gives white children a false sense of superiority, which may later lead to prejudice and racism. (Boutte, 1999) Marva Collins (2002) gives special emphasis to the fact that this is part of the original reasons for schools in the first place social control, maintaining the status quo, etc The original objectives of schools were to socialize people into their place. She feels that every teacher must acknowledge the reasons and foundations that our school system is originally based on for their own understanding of some of the behaviors that theyre seeing in their classrooms. Schools, for many students, particularly those from the lowest socioeconomic level of society, offer few opportunities for self and social empowerment. For these students, schooling is a place that disconfirms rather than confirms their histories, experiences, and dreams. In part, this alienation is expressed in the high rate of student absenteeism

and school violence, and in the refusal of many students to take seriously the academic demands and social practices of schools. (Giroux, 1984, p.189) Based on their poor performance on achievement tests, some students, often Black and Hispanic are typically placed in lower reading and math groups in elementary school. More and more educators are calling this testing and tracking system a form of social reproduction and oppression. Researchers have found that this separation of low achievers from high achievers is counterproductive to the alleged purposes of testing and tracking: to more effectively meet the needs of individual students. What often happens is that these students self-esteem suffers along with their effort and achievement (Anyon, 1981; Bowles & Gintis, 1986; Jencks et al, 1972, Oakes, 1986; Weinstein, 1986, 1991). Many educational leaders and advocates actively oppose ability grouping and tracking (e.g., the National Middle Schools Association, the National Education Association, the Carnegie Endowment for Children, National Association for the Education of Young Children) (Wheelock and Hawley, 1992). The bottom line is that educators have the responsibility of teaching ALL children. Whenever a particular segment of the school population is not succeeding, the implication is that it is worth examining the way things are done instead of continuing with business as usual (Boutte, 1999; Kunjufu, 1986; Sleeter, 1993). Contemporary Research on the Human Brain The popularity of behaviorism in the 1950s and 1960s inspired a generation of educators to pursue rewards as a teaching strategy. We knew very little about the brain at that time, and rewards seemed cheap, harmless, and often effective. But there was more to the use of rewards than most educators understood. Surprisingly, much of the original research by Watson and Skinner was misinterpreted. (Jensen, 1998) The stimulus-response rewards popularized by behaviorism were effective only for simple physical actions. Yet schools often try to reward students for solving challenging cognitive problems, writing creatively, and designing and completing projects. Theres an enormous difference in how the human brain responds to rewards for simple and complex problem-solving tasks. Short-term rewards can temporarily stimulate simple physical responses, but more complex behaviors are usually impaired, not helped, by rewards (Deci, Vallerand, Pelletier, and Ryan, 1991; Kohn, 1993).

In addition, the behaviorists made a flawed assumption: that learning is primarily dependent on a reward. Jensen (1998) reveals that rats as well as humans will consistently seek new experiences and behaviors with no perceivable reward or impetus. Experimental rats responded positively to simple novelty. Presumably, novelty seeking could lead to new sources of food, safety, or shelter, thus enhancing species preservation. Choice and control over their environment produced more social and less aggressive behaviors (Mineka, Cook, and Miller, 1984). Is it possible that curiosity or the mere pursuit of information can be valuable by itself? That just for the sake of not being stupid is reward enough? Studies confirm this happens, and humans are just as happy to seek novelty (Restak, 1979). The old paradigm of behaviorism told us that to increase a behavior, we simply need to reinforce the positive. If theres a negative behavior exhibited, we ought to ignore or punish it. This way of understanding classroom behavior seemed to make sense for many. But our understanding of motivation and behavior has changed. Tokens, gimmicks, and coupons (extrinsic rewards) no longer make sense when compared with more attractive alternatives (Kohn, 1993; Jensen, 1998). Jensen (1998) is careful to note that neuroscientists take a different view of rewards. First, the brain makes its own rewards. They are called opiates, which are used to regulate stress and pain. These opiates can produce a natural high, similar to morphine, alcohol, nicotine, heroin, and cocaine. Like these drugs extrinsic rewards may ultimately lead to a dulling of the brains natural system of rewards. This reward system is based in the brains center, the hypothalamic reward system (Nakamura, 1993). The pleasureproducing system lets you enjoy a behavior, like affection, sex, entertainment, caring, or achievement. You might call it a long-term survival mechanism. Its as if the brain says, That was good; lets remember that and do it again! (Intrinsic motivation) Working like a thermostat or personal trainer, your limbic system ordinarily rewards cerebral learning with good feelings on a daily basis. Students who succeed usually feel good, about themselves, and thats reward enough for most of them. Achievement Motivation Theory

. motivational characteristics, as well as self-concept and self-esteem, are themselves shaped by a students history of success and failure in and out of school (Thomas, 1980, p. 214). Thomas (1980) and others have demonstrated a strong relationship between student attitudes towards school and towards themselves as learners on the one hand, and their achievement motivation and academic success on the other (Anyon, 1981; Brophy, 1987; Covington, 1984; Giroux, 1984; Ogbu & Matute-Bianchi, 1986; Weinstein, 1984). Children can choose to shut down the learning process if they dont see any value in the effort required or if they are sure they will fail (Atkinsom, 1957, 1964; Brophy, 1987; Covington, 1984, 1992; Weiner, 1972) A number of educators believe that student attitudes and academic success or failure are in large part due to the nature of their relationships in and with the schools. The views of Covington (1984, 1992), Weinstein (1984, 1991), Cummins (1986), and Ogbu & Matute-Bianchi (1986) about school failure represent the underpinnings of this classroom approach. Covington (1984) found that children who consistently do poorly in school begin to believe that they are not as academically capable as other children. In order to cope with such a belief, these children tend to protect themselves with defense mechanisms such as feigned apathy, excuses for missing work, or disruptive behavior, all examples of negative motivation. Lack of effort in school typically results in low academic achievement. Typically in classrooms there is a limited variety of assignments and activities offered to students. Those who do well on them become the high achievers and those who do poorly become the low achievers. These limited performance opportunities allow few students to shine, since implementing a restricted number of tasks does not capture the many different types of intelligences (Rosenhotz & Simpson, 1984; Gardner, 1993). Grades are typically determined by very narrow criteria. For example, reading and writing skills are given most of the attention in schools, whereas oral and narrative skills, artistic skills, leadership skills, imagination, and creativity are not given the same respect and credit (Heath, 1983, 1986; Boykin, 1994; Rosenholtz, 1979; Phillips, 1972). Consequently, those students with the strongest reading and writing skills excel early on

in school, develop stronger academic self-esteem than those with skills that are weaker, and typically end up being the high achievers. Self-Worth Theory: Motives as the Protection of Personal Worth According to the self-worth theory of achievement motivation (Covington & Beery, 1976; Covington & Berry, 1976; Covington, 1984, 1992, 1997), the most critical factor in determining student attitudes and behavior is a sense of self-worth. The key to self-worth is students perceptions of their own ability, especially in comparison to others. In an imagined hierarchy of self-worth criteria, students would list ability first, followed by performance and effort. Berry (1975) explained the theory as the equating of ability with worth (ability = worth), and claimed this is what lies at the heart of self-worth dynamics. Students learn to avoid shame and humiliation due to failure by choosing not to try. This is a matter of saving face, where a sense of pride takes precedent over possible, yet unlikely, and accomplishment through effort. The problem with this strategy is that teachers expect students to at least try and are often inclined to punish them if they dont. This is the double-edged sword of the theory (Covington & Omelich, 1979). In order to protect their sense of worth, students may not risk failure on an assignment by working on it. However, by not trying on an assignment, the students risk criticism and possible consequences imposed on them by their teacher and by their families. What Covington suggests is that many disruptive off-task behaviors teachers must contend with on a daily basis are reactive behaviors, resulting from a history of unpleasant classroom and /or school-wide experiences that the students have had, situations that have designated learning as an ability game. In order to prevent students from developing a failure orientation, Covington advocates a classroom environment which promotes student success through individual mastery learning and tantalizing tasks which result in effort through intrinsic motivation (Covington, 1997, 1992; Covington & Teel, 1996). School structures sometimes perpetuate feelings of low self-worth and low levels of motivation among students. Teachers and parents worry that [students] are

unmotivated, Raffini (1988) says. In reality, they are highly motivated to protect their sense of self-worth. He suggests using individual goal-setting structures, outcome-based instruction and evaluation, attribution retraining, and cooperative learning activities to remove motivational barriers and redirect student behavior away from failure-avoiding activities in academic settings. Raffini describes how these four strategies can aid in promoting the rediscovery of an interest in learning: Individual goal-setting structures allow students to define their own criteria for success. Outcome-based instruction and evaluation make it possible for slower students to experience success without having to compete with faster students. Attribution retraining can help apathetic students view failure as a lack of effort rather than a lack of ability. Cooperative learning activities help students realize that personal effort can contribute to group as well as individual goals. Differential Teacher Expectations Rhona Weinsteins (1984, 1986, 1991) research in regard to school failure focuses on varying levels in students school achievement in terms of teacher expectations and classroom and school structure. She claims that many students who become at risk for school failure do so because they become labeled low-achievers early in their school years. Weinstein has found that teachers have lower expectations for students identified as low-achievers and treat them qualitatively differently than their more high achieving students. In classrooms where less differential treatment occurs, teachers have more positive relationships with students and provide a variety of positive feedback to them in the context of diverse tasks and mixed-ability group structures. Students share more responsibility for their own learning and evaluation, and assessment is used as a basis for learning and evaluation, and assessment is used as a basis for learning as opposed to a measure of ability and performance. In classes where differential treatment does occur, students are generally clearly categorized in some manner, and for those who are negatively slotted, learning often becomes an exercise in frustration, leading to poor

achievement, lower positive motivation, and other counterproductive school behaviors and attitudes (Marshall & Weinstein, 1986). If there are leadership opportunities or occasions when student feedback is solicited, it is normally the higher achievers who are called on (Weinstein, Marshall, Brattesani, & Middlestadt, 1982). This results in unrecognized and underdeveloped talent among those students who have been labeled low achievers (Cummins, 1986; Thomas, 1980; Verble, 1985). At the present time in American schools, students have very few opportunities to participate in decision-making relative to curriculum, and few choices are offered to students when they are given assignments (Covington, 1992). Many educators are not sensitive to the needs of culturally and ethnically diverse students, nor do most teachers hold similar points of view as their students (Gay, 1993). The disparities and socio-cultural gap between teachers and many elementary school children continues to increase. In her discussion of the disparities, Gay points out that even though the percentage of elementary school children who are African American, Latino/a American, Asian American, Native American, poor, and limited English speaking is increasing significantly, the number of teachers with similar backgrounds to these children is declining. It is critical that teachers examine and change their basic assumptions and beliefs. They must believe that ALL children can learn regardless of their ethnic group, gender, or social class (Banks, 1992; Collins, 2002). According to Cummins (1986), schools and teachers have traditionally failed to honor African-American heritage and culture by not acknowledging multiple perspectives and diverse cultures in curriculum and instruction. This approach disempowers students rather than empowering them through validation of their cultural heritage (Banks, 1991/92). That missing empowerment, however, is experienced by a majority of white children whose Euro-centric culture has been the traditional focus in American schools. As a way of coping with racial discrimination and the devaluing of their cultural heritage in the classroom, many African American students have created a type of counter-culture to protect their self-esteem and sense of identity (Ogbu & MatuteBianchi, 1986). Inner-city African American students often struggle between representing their own cultural norms or conforming to mainstream standards. As a part of this conflict, students often resist doing well for a variety of reasons including the stigma of

acting white (Fordham and Ogbu, 1986). This attitude often reveals itself in the form of negative motivation. From this perspective, African American underachievers may be thought of as youngsters who have the ability to do well in school, but choose, consciously or unconsciously, to underachieve. Misunderstanding of cultural behaviors has been shown to lead to errors about childrens intellectual potential, which results in mislabeling, misplacement, and mistreatment of children (Hilliard, 1992). Teachers often perceive African American students from working or low-income backgrounds as incapable of high quality academic work (Ladson-Billings, 1994). In addition to African American children, the harmful consequences of ability grouping fall heavily on Latin/a, immigrant, and poor children (Wheelock & Hawley, 1992). Therefore, these children are subjected to low-quality educational experiences (Boutte, 1999). Interestingly, teachers rarely attribute their problems with children of color to ineffective teaching approaches. The overall implication of the research on cultural learning patterns is that if teachers are to be effective, they need to be prepared to teach children who are not white as well as white children (Ladson-Billings, 1994). Providing children with an equitable and effective pedagogy demands that teachers use the language and understandings that children bring to school to bridge the gap between what students know and what they need to learn (Ladson-Billings, 1994). In addition to cultural learning styles and patterns, subconscious patterns of gender bias can influence the behavior of teachers and affect the childs self image (Kaplan & Aronson, 1994). Study after study has shown that male students consistently demand and receive more attention than females (Sadker, Sadker, and Long, 1993). When giving feedback about childrens work, teachers often tell boys that they have not tried hard enough and encourage the boys to keep working. On the other hand, girls are merely told that their answers are wrong (with no additional feedback) (Sadker, Sadker, & Long, 1993). After years of this type of feedback, boys become persistent, and girls give up (Streitmatter, 1994). Teachers must work to overcome such biases. Gender differences also interfere with effective cross-cultural communication. The majority of the elementary teaching profession is female and female-oriented. Therefore, the culture of the school often reflects a female perspective (Boutte, 1999). The

10

disproportionate number of males who are subjected to disciplinary actions especially African American and Latino males (McCoy and Boutte, 1995; Sleeter, 1993) may often be the result of males trying to thrive in a female-oriented environment. In schools across the nation, boys are more likely to be scolded and reprimanded in classrooms even when the observed conduct of boys and girls does not differ (Sadker, Sadker, and Long, 1993). Additionally, boys are far more likely to be identified as exhibiting learning disabilities, reading problems, and mental retardation. They also receive lower grades, are more likely to repeat grades, and are less likely to complete high school. Unfortunately, a lot of females do not understand the male culture and cannot speak their language. For example, when boys engage in rough-and-tumble play on the playground or in the halls, instead of just saying, Quit the horseplay, many female teachers may misinterpret it as fighting; although this is commonplace among boys. The manner in which female teachers treat males may be influenced by how they (female teachers) feel about the males in their lives (e.g, their husbands, babys daddies, brothers, fathers, ex-boyfriends, uncles, sons, etc.) (Kunjufu, 1986). Kunjufu notes that the sexism issue becomes even more complex with white teachers who teach black males, since many of the female teachers may have never had direct contact with a black male. Kunjufu questions that white female teachers see when they look at black males. Do they see a Jesse Jackson or a drug addict? The way teachers view and treat black males depends on prior experiences and societal perspectives about black males. Credence is added to the claims that elementary schools are more female-oriented when we observe honor rolls at many middle schools. Recently, one of the authors attended an honor roll program for sixth, seventh, and eighth graders. Approximately eighty percent of the honorees were white females. Only a few males were presented with awards and even fewer African American children. All of the Asian children at the school received awards. The point is that the honorees basically looked just like the teachers white females! (Boutte, 1999) Teachers have the responsibility for creating a positive learning environment in their classes. In the hectic day-to-day routine, it is easy for teachers to forget the tremendous influence they have on their students. Even when they carry out seemingly noninstructional actions, such as smiling at students or showing disapproval, they are engaged in pedagogy (Ladson-Billings, 1994).

11

All school personnel, including secretaries, cafeteria employees, and so forth, would benefit from diversity sensitivity workshops which focus on treating all children and families with respect. (Boutte, 1999) Goal Orientation Theory Goal orientation theory has emerged as one of the preeminent approaches to motivation (e.g., Weiner, 1990). The theory was developed specifically to explain childrens learning and performance on academic tasks and in school settings. As such, it is the most relevant and applicable motivational theory for understanding and improving learning and instruction (Pintrich & Schunk, 1996). The theory goes beyond directionality to consider the quality of motivation by attending to the purposes for engaging in achievement behavior and how students go about engaging in and responding to achievement situations (Ames, 1992). Thus, these orientations are more than just underlying needs of the individual or the value the individual places on the learning situation. Instead, they can be thought of as cognitive schema that provides an organizing framework within which students interpret and react to learning situations (Dweck, 1986). According to Gheen et al. (2000) two achievement orientations have received the most attention. The orientations have been labeled in a variety of ways by researchers, however, here, the two orientations that have been the primary focus of past research and theory will be referred to as task and performance goals. Task goals are also referred to as mastery or learning goals. Performance goals are also referred to as ego-involved or ability goals. A task goal orientation reflects a striving for valuable learning based on effort that results in a desire to focus on improvement and mastery. In contrast, a performance goal represents an orientation to demonstrate ones ability often in relation to others (Maehr & Midgley, 1991b). Further more, just as personal goal orientations provide a cognitive framework for organizing and interpreting learning situations, classroom goal structures similarly influence students academic outcomes (Gheen, Hrunda, Middleton, & Midgley, 2000). Goal theorists stress that the context of the learning situation influences students adoption of task and performance goals, and that learning contexts are structured as either task goal focused and/or performance goal focused because teachers convey these goals

12

about the purpose of achievement behavior through learning tasks, grouping of students, evaluation practices and even use of time (Ames, 1992). In general, and mirroring what is found for personal goals, studies of elementary and middle school students find that a task goal structure is associated with positive academic beliefs and behaviors, whereas a performance goal structure is associated with a less adaptive pattern, including the use of avoidance behaviors (e.g., Ames & Archer, 1988; Roeser, Midgley, &Urdan, 1996; Ryan, Gheen, & Midgley, 1998; Urdan, Midgley, & Anderman, 1998). While goal theory was initially developed with the assumption that goal orientations are adopted by and operate similarly for all students regardless of gender or ethnicity (Ames, 1992), investigations using the goal theory perspective have found gender and ethnic differences that lead to questions regarding the validity of this assumption (Gheen, Hruda, Middleton, Midgley, 2000). For example, with respect to gender, studies have found that males sometimes report higher levels of performance goals than do females (Roeser, Midgley & Urdan, 1996; Ryan, Hicks, & Midgley, 1997). Ethnic differences, though less studied, are also found in some investigations. For example, the maladaptive association of a performance goal with self-handicapping was found to be stronger among African-American than European-American students (Midgley, Arunkumar & Urdan, 1996). Rather than differences in the adoption of goals, variance among ethnic groups generally surfaces in differing associations of goals to outcomes. That is, ethnicity appears to moderate the relation of goals to outcomes. With regard to school transitions, although very little research has been done, there is some evidence that the middle school transition may be particularly problematic for minority youth (Simmons, Black & Zhou, 1991; Simmons & Blyth, 1987). Goal contexts may be differentially influential for some students depending on demographic variable, such as gender or ethnicity, or other background variables that may make some students more susceptible to maladaptive outcomes, such as low self-efficacy or achievement. Attribution Theory The first point to be emphasized is that students perceptions of their educational experiences generally influence their motivation more than the actual, objective reality of those experiences (Anderman & Midgley, 1996). For example, a history of success in a given subject area is generally assumed to lead one to continue persisting in that area.

13

Weiner (1985), however, pointed out that students beliefs about the reasons for their success will determine whether this assumption is true. Students attributions for failure are also important influences on motivation. When students have a history of failure in school, it is particularly difficult for them to sustain the motivation to keep trying. Students who believe that their poor performance is caused by factors out of their control are unlikely to see any reason to hope for an improvement. In contrast, if students attribute their poor performance to a lack of important skills or to poor study habits, they are more likely to persist in the future. The implications for teachers revolve around the importance of understanding what students believe about the reasons for their academic performance. Teachers can unknowingly communicate a range of attitudes about whether ability is fixed or modifiable and their expectations for individual students through their instructional practices. (Graham, 1990). Self-Determination Theory Another motivational theory of particular importance for middle school educators is self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 1985). This theory describes students as having three categories of needs: needing a sense of competence, of relatedness to others, and of autonomy. Competence involves understanding how to, and believing that one can, achieve various outcomes. Relatedness involves initiating and regulating ones own actions. Most of the research in self-determination theory focuses on the last of these three needs (Anderman & Midgley, 1998). Within the classroom, autonomy needs could be addressed through allowing some student choice and input on classroom decisionmaking. For young adolescent students, with their increased cognitive abilities and developing sense of identity, a sense of autonomy may be particularly important. Students at this stage say that they want to be included in decision-making and to have some sense of control over their activities. Unfortunately, research suggests that students in middle schools actually experience fewer opportunities for self-determination than they did in elementary school (Midgley & Feldlaufer, 1987). Deci, Vallerand, Pelletier, and Ryan (1991) summarized contextual factors that support student autonomy. Features such as the provision of choice over what types of

14

tasks to engage in and how much time to allot to each are associated with students feelings of self-determination. In contrast, the use of extrinsic rewards, the imposition of deadlines, and an emphasis on evaluations detract from a felling of self-determination and lead to a decrease in intrinsic motivation (Anderman & Midgley, 1998). It is important to recognize that supporting student autonomy does not require major upheaval in the classroom or that teachers relinquish the management of students behavior. Even small opportunities for choice, such as whether to work with a partner or independently, or whether to present a book review as a paper, poster, or class presentation, can increase students sense of self-determination. Finally, it is important to recognize that students early attempts at regulating their own work may not always be successful. Good decisionmaking and time management require practice. Teachers can help their students develop their self-regulation by providing limited choices between acceptable options, by assisting with breaking large tasks into manageable pieces, and by providing guidelines for students to use in monitoring their own progress (Anderman & Midgley, 1998) Models for Classroom Reform Research by DeBruin-Parecki, Teel, and Covington (1998) have revealed a teaching methodology that addresses low student self-esteem, negative motivation, and achievement among inner-city African-American middle school students. Based on motivation and school failure theories, teaching and grading strategies were developed which incorporated multiple intelligences and a multicultural perspective. Four key features were: non-competitive, effort-based grading; multiple performance opportunities; responsibility/choice; and validation of cultural differences. By building the theoretical principles of these four features into their classroom approach, they reached the goal of promoting successful academic performance among formerly lowachieving students, and consequently, built together with students a different and more positive view of their academic abilities and potential. Noncompetitive Classroom Structure/Innovative Grading System In questionnaires, the majority of the students said they wanted to receive an A or B. When they actually saw those grades on assignments, progress reports, and on report

15

cards, they expressed excitement and pride. Even Cs were well received by students who were getting Ds and Fs in their other classes. (DeBruin-Parecki, et al., 1998) One of the most important principles guiding this approach is to create a classroom environment in which individual effort and group cooperation are encouraged rather than competition and a win/lose scenario. Lessons are to be developed which students can complete successfully either the first time or as a result of revising them using the teachers feedback. Teachers should stress effort and improvement more than standardized ability because we want to give the students every opportunity to learn from their assignments (DeBruin-Parcki, et al., 1998). Grades should be determined on an individual basis, taking into consideration cooperation, participation, effort, and quality of work. With individual improvement emphasized rather than comparison with others on a class-wide basis. In interviews students attributed their success partly to the encouragement they received to revise and resubmit work completed below the standards expected by the teacher. They also responded well to being allowed to turn in work late, knowing they would only receive a moderate penalty. (DeBruin-Parcki, et al., 1998) Multiple Performance Opportunities Another goal is to help students recognize their own strengths and talents by giving them the opportunity to demonstrate imagination and creativity through their oral, narrative, and artistic skills while still developing their more traditional reading and writing skills. By grading them on a number of different kinds of assignments, students are likely to redefine their own abilities as they began to see themselves in a different light (Rosenholtz & Simpson, 1984; Weinstein, 1984). Skits, worksheets, quizzes, tests, oral presentations, book talks, art projects, map work, note-taking assignments, reading sessions, and group assignments are but a few examples. All of these types of activities can form the basis for a final quarter grade. through the variety of assignments offered to the students, many of them showed that they were quite artistic, imaginative, and creative. During group work, other talents the students possess often came through as they exhibited skills in leadership, organization, cooperation, and teamwork. (DeBruin-Parcki, et al., 1998) The use of peers in a cooperative learning setting (to solve academic tasks and to prepare reports) has been shown to increase student achievement more than in a teacher-

16

directed setting (Berns, 1993). Although cooperative-learning strategies may work for some students, it may be ineffective for others who gave different learning styles. Therefore, educators should use a balance of teaching methods such as lecture, discussion, inquiry, learning centers, cooperative groups, individualized instruction, computerized instruction, and the like (Boutte, 1999). Student Responsibility and Choice In order to give students some dimensions of ownership of the classroom, the teacher should provide them with certain responsibilities. For example, students can be given leadership opportunities in the classroom on a regular basis as classroom officers. Also, including students in on the criteria for assessing the various assignments is encouraged. For example, a teacher could use a matrix on the board and have students participate in defining what will be considered excellent, good, and mediocre work. Choice and opportunities to influence the teachers curriculum decisions give students a sense of authority and reduce their resistance to the teachers agenda. Validation of Cultural Differences Who wants to be in a place where theyre being tolerated? Id much rather be in a place where Im celebrated. White teachers commonly insist that they are color blind and that they see children and do not see race (Boutte, LaPoint, & Davis, 1993; Sleeter, 1993; Scholfield, 1997). The denial of the importance of race in this society often results in teachers trying to teach all children in the same manner typically from a Eurocentric perspective (Boutte, LaPoint, & Davis, 1993). Teaching from a monocultural perspective keeps teachers from communicating effectively cross-culturally, and they often fail to correctly interpret the messages that children are sending. Furthermore, many white teachers do not respect childrens communication styles and tend to view African Americans and Latino/a Americans (in particular) in a pathological manner (Heath, 1983). That is, children of color and poor childrens homes and communities tend to be viewed as dysfunctional, and teachers believe that the children lack ability and motivation (Sleeter, 1993). Culturally idiosyncratic communication styles that may be praised in the childs home and community may be looked upon with disdain by teachers and school personnel.

17

Literature suggests that the teacher put together a classroom library of historical fiction and biographies that represent all of the students cultural backgrounds. The typical classroom library should consist of African-American, Asian-American, European-American, Latino-American, and Native-American literature. (Delpit, 1988, 1992; Ladson-Billings, 1992; Shade, 1989, 1994; Hale-Benson, 1994; Graham, 1994; Irvine, 1990) On a questionnaire at the end of the second year, when asked how they felt about reading books about people of their own culture, two African-American students wrote: I feel nice because most books are about White People. It is nice to hear something good about my race some time. (DeBruin-Parecki, et al., 1998) As a means of addressing the identity crisis that Ogbu & Matute-Baianchi (1986) have written about, relevance to the students lives should be built into the curriculum. Current events should be discussed on a regular basis, and whenever there are particular news stories students are interested in, they become a topic of conversation. - SCORE Students who are engaged in their work are energized by four goals Success, curiosity, originality, and satisfying relationships (Strong, 1995). Each of which satisfies a particular human need: Success (the need for mastery), Curiosity (the need for understanding), Originality (the need for self-expression), Relationships (the need for involvement with others). These four goals form the acronym for Richard Strong and his colleagues model of student engagement SCORE. Under the right classroom conditions and at the right level for each student, they can build the motivation and Energy (to complete the acronym) that is essential for a complete and productive life (Strong, 1995). These goals can provide students with the energy to deal constructively with the complexity, confusion, repetition, and ambiguities of life (the drive toward completion). Convincing Kids They Can Succeed

18

Students want and need work that enables them to demonstrate and improve their sense of themselves as competent and successful human beings (Strong, 1995). This is the drive toward mastery. But success, while highly valued in our society, can be more or less motivational. People who are highly creative, for example, actually experience failure far more often than success. Before we can use success to motivate our students to produce high-quality work, we must meet three conditions: (Strong, 1995) 1. 2. 3. We must clearly articulate the criteria for success and provide clear immediate, and constructive feedback. We must show students that the skills they need to be successful are within their grasp by clearly and systematically modeling these skills. We must help them see success as a valuable aspect of their personalities.

Arousing Curiosity Students want and need work that stimulates their curiosity and awakens their desire for deep understanding. How can we ensure that our curriculum arouses intense curiosity? By making sure it features two defining characteristics: the information about a topic is fragmentary or contradictory, and the topic relates to students personal lives. (Strong, 1995) Encouraging Originality Students want and need work that permits them to express their autonomy and originality, enabling them to discover who they are and who they want to be. Unfortunately, the ways schools traditionally focus on creativity actually thwart the drive toward self-expression. Strong offers several reasons for this: First, schools frequently design whole programs (art, for example) around projects that teach technique rather than self-expression. Second, very often only students who display the most talent have access to audiences, thus cutting off all other students from feedback and a sense of purpose. Finally, and perhaps most destructive, schools frequently view creativity as a form of play, and thus fail to maintain the high standards and sense of seriousness that make creative work meaningful. Fostering peer relationships

19

Students want and need work that will enhance their relationships with people they care about. This drive toward interpersonal involvement is pervasive in all our lives. After taking into consideration the needs and drives mentioned, this model poses four important questions that teachers must ask themselves in order to score the level of engagement in their classrooms. 1. 2. 3. 4. Under what conditions are students most likely to feel that they can be successful? When are students most likely to become curious? How can we help students satisfy their natural drive toward self-expression? How can we motivate students to learn by using their natural desire to create and foster good peer relationships? Much of whats discussed is already taking place in classrooms across the country. The point of the SCORE model of engagement is first to help teachers discover what they are already doing right and then to encourage the cultivation of everyday classroom conditions that foster student motivation and success. Rethinking Motivation The concept of score is a metaphor about performance, but one that also suggests a work of art, as in a musical score. By aiming to combine achievement and artistry, the SCORE model can reach beyond strict dichotomies of right/wrong and pass/fail, and even bypass the controversy about intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, on which theories of educational motivation have long been based. (Strong, 1995) Extrinsic motivation a motivator that is external to the student or the task at hand (Strong, 1995) has long been perceived as the bad boy of motivational theory. In Punished by Rewards, Alfie Kohn (1993) lays out the prevailing arguments against extrinsic rewards, such as grades and gold stars. He maintains that reliance on factors external to the task and to the individual consistently fails to produce any deep and longlasting commitment to learning. Intrinsic motivation, on the other hand, comes from within, and is generally considered more durable and self-enhancing (Kohn 1993). Still, although intrinsic 20

motivation gets much better press, it, too, has its weaknesses. As Kohn argues, because intrinsic motivation is a concept that exists only in the context of the individual, the prescriptions its proponents offer teachers, are often too radically individualized, or too bland and abstract, to be applied in classroom settings (Strong, 1995). Several other researchers have criticized current instructional practices that sometimes hinder the development of motivation. Representative of these critics are Stipek (1988) and Eccles, Midgeley, and Adler (1984). Stipek makes a strong case for strengthening the degree of intrinsic motivation students feel for learning. While she does not argue for the complete elimination of extrinsic reward systems, she believes that there are many benefits to maximizing intrinsic motivation and many ways to foster it. Challenging but fair task assignments, the use of positive classroom language, mastery-based evaluation systems, and cooperative learning structures are among the methods she suggests. Perhaps it is the tradition of separating extrinsic and intrinsic motivation that is flawed. Robert Sternberg and Todd Lubart recently addressed this possibility in defying the Crowd (1995). They assert that any in-depth examination of the work of highly creative people reveals a blend of both types of motivation. School Leadership and Student Motivation Much of the recent research on student motivation has rightly centered on the classroom, where the majority of learning takes place and where students are most likely to acquire a strong motivation to gain new knowledge. Making the classroom a place that naturally motivates students to learn is much easier when students and teachers function in an atmosphere where academic success and the motivation to learn are expected and rewarded. Such an atmosphere, especially when motivation to learn evolves into academic achievement, is a chief characteristic of an effective school. (Renchler, 1992) An environment that nurtures educational motivation can be cultivated in the home, in the classroom, or throughout an entire school. One of the most effective avenues for engendering student motivation is a schools culture. According to Deal (1987), school culture can be embodied and transformed through channels such as shared values, heroes, rituals, ceremonies, stories, dialogue, and cultural networks. Davis (1989) suggests using a wide variety of activities and symbols to communicate motivational goals. Visible symbols, he says, illustrate and confirm what is considered

21

to be important in school. He suggests using school newsletters, statements of goals, behavior codes, rituals, symbols, and legends to convey messages of what the school really values. Staging academic awards assemblies, awarding trophies for academic success and displaying them in trophy cases, scheduling motivational speakers, and publicizing students success can help them see that the desire to be successful academically is recognized and appreciated. Klug (1989) notes that school leaders can influence levels of motivation by shaping the schools instructional climate, which in turn shapes the attitudes of teachers, students, parents, and the community at large toward education. By effectively managing this aspect of a schools culture, principals can increase both student and teacher motivation and indirectly impact learning gains, Klug says. School administrators can take advantage of times of educational change by including strategies for increasing student motivation. Acknowledging that school restructuring is inevitable, Maehr (1991a) challenges school leaders to ensure that motivation and the investment in learning of students will be enhanced as a result of school reform. School leaders have seldom considered motivation vis--vis the current restructuring movement, he says, and few have considered that the school as an entity in its own right, may have effects that supersede those of individual classrooms and the acts of individual teachers. A positive psychological environment strongly influences student motivation, says Maehr (1991a). School leaders can create this type of environment by establishing policies and programs that: Stress goal setting and self-regulation/management Offer students choices in instructional settings Reward students for attaining personal best goals Foster teamwork through group learning and problem-solving experiences Replace social comparisons of achievement with self-assessment and evaluation techniques Teach time management skills and offer self-paced instruction when possible

22

Eccles, Midgeley, and Adler argue that motivation would increase if students were asked to assume greater autonomy and control over their lives and learning as they proceed through higher-grade levels. They note that this process rarely takes place in most schools and recommend that school leaders create an environment that would facilitate task involvement rather than ego involvement, particularly as children enter early adolescence. The work of Leithwood and Montgomery (1984) is especially helpful in understanding the connections between a school administrators motivation and the level of motivation that exists among students. According to Leithwood and Montgomery, school administrators progress through a series of stages as they become more effective. At their highest level of effectiveness, they come to understand that people are normally motivated to engage in behaviors which they believe will contribute to goal achievement. The strength of ones motivation to act depends on the importance attached to the goal in question and ones judgment about its achievability. Motivational strength also depends on ones judgment about how successful a particular behavior will be in moving toward goal achievement. Personal motivation on the part of the principal can translate into motivation among students and staff through the functioning of goals, according to Leithwood and Montgomery. Personally valued goals, they say, are a central element in the principals motivational structure a stimulus for action. Establishing, communicating, and creating consensus around goals related to motivation and educational achievement can be a central feature of a schools leaders own value system. Here are a few other steps school leaders can take to improve student motivation at the school level: (Leithwood and Montgomery, 1984; Grossnickle, 1989; Renchler, 1992) Analyze the ways that motivation operates in your own life and develop a clear way of communicating it to teachers and students. Seek ways to demonstrate how motivation plays an important role in noneducational settings, such as in sports and in the workplace. Show students that success is important. Recognize the variety of ways that students can succeed. Reward success in all its forms. Develop or participate in in-service programs that focus on motivation.

23

Involve parents in discussing the issue of motivation and give them guidance in fostering it in their children. Demonstrate through your own actions that learning is a lifelong process that can be pleasurable for its own sake.

Conclusion Nearly all educators deal with the issue of motivation. In fact, in the first few weeks of school, teachers often mentally group students into the categories of motivated and unmotivated (Jensen, 1998). Jensen feels that the rest of the school year usually plays out these early perceptions of who is ready to learn and who isnt. A slew of tools, strategies, drugs, and techniques are marketed to a hungry audience of frustrated educators who work with hard to reach or perpetually unmotivated students. An empathetic change by teachers and staff toward a focus on understanding instead of being understood is perhaps overdue. In middle level schools, it is important to emphasize mastery and improvement, rather than relative ability and social comparison. Empirical evidence suggests that middle schools tend to stress relative ability and competition among students more, and effort and improvement less, leading to a decline in task goals, ability goals, and academic efficacy (Schumacher, 1998). Working in groups, focusing on effort and improvement, and being given choices all support a more positive task-focused on effort and improvement, and being given choices all support a more positive task-focused goal structure (Anderman & Midgley, 1996). Middle school teachers often teach many students over the course of a school day, and for a relatively short period of time. Given such brief contact with so many, it is easy to underestimate the influence that ones teaching practices can have on any one individual. Current moves to implement the middle school philosophy may provide a more facilitative schedule for both teachers and students, but even in a highly structured middle school, teachers can take specific steps to provide a learning environment that will promote the motivation of ALL students (Anderman & Midgley, 1996).

24

REFERENCES: Ames, C. (1984). Achievement attributions and self-instructions under competitive and individualistic goal structures. Journal of Educational Psychology, 76, 478-487. Ames, C. (1992). Classrooms: Goals, structures, and student motivation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 79, 409-414. Anderman, E.M., and Maehr, M.L. (1994) Motivation and schooling in the middle grades. Review of Educational Research, 64(2), 287-309. Anderman, Eric M., and Midgley, Carol. (1996) Changes in Achievement Goal Orientations After the Transition to Middle School. Paper presented at the biennial meeting of the Society for Research on Adolescence, Boston, MA. Banks, J. A. (1991/92) Multicultural education: For freedoms sake. Educational Leadership, 49, 32-36. Berry, R. G. (1975). Fear of failure in the student experience. Personnel and Guidance Journal, 54, 190-203. Boutte, G.S. (1999). Multicultural Education. Raising Consciousness. Boston: Wadsworth. Boutte, G.S., B. McCoy, and B.D. Davis. (1995). Helping African-American students maintain and adopt their communication styles: A challenge for educators. The Negro Education Review 46(1-2): 10-21. Bowles, S. & Gintis, H. (1986). Schooling in capitalist America. New York: Basic Books. Boykin, A. W. (1986). The triple quandary of Afro-American children. In U. Neisser (Ed.), The school achievement of minority children (pp.57-92). Hillsdale, N.J.: Erlbaum. Boykin, A. W. (1994). Afrocultural Expression and its implications for schooling. In E.R. Hollins, J. E. King, & W.C. Hayman (Eds.), Teaching diverse populations: Brophy, J. E. (1983). Research on the self-fulfilling prophecy and teacher expectations. Journal of Educational Psychology, 75, 631-661. Brophy, J.E. (1987). Synthesis of research on strategies for motivating students to learn. Education Leadership, 40-48. Brown, A.D., D. Ash, M. Rutherford, K. Nakagawa, A. Gordon, and J. Campione.

25

(1993). Distributed Expertise in the Classroom. In Distributed Cognitions: Psychological and Educational Considerations, edited by G. Salomon. New York: Cambridge University Press. Chen, M., and E. Goldring. (1992) The impact of classroom diversity on teachers perspectives of their schools as workplaces. EDRS. ED 354 615. Cohen, E.G. (1994). Designing Groupwork: Strategies for the Heterogeneous Classroom. 2nd Edition. New York: Teachers College Press. Collins, Marva N. (2002) Speech at Western Michigan University. Jan. Cooper, C. R.; Jackson, J. F., Azmitia, M. & Lopex, E. M. (1998). Multiple selves, multiple worlds: Three useful strategies for research with ethnic minority youth on identity, relationships, and opportunity structures. In V. C. McLoyd (Ed.) Studying minority adolescents: Conceptual, methodological, and theoretical issues (pp. 111-125). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Covington, M. V. (1984). The self-worth theory of achievement motivation: Findings and implications. The Elementary School Journal, 85(1), 5-20. Covington, M.V. (1992). Making the grade: A self-worth perspective on motivation and school reform. New York: Cambridge University Press. Covington, M. V. (1996). The myth of intensification. Educational Researcher, 25(8), 2427. Covington, M. V. (1997). Self-worth and motivation. New York: Cambridge University Press. Covington, M.V. & Berry, R. G. (1976). Self-worth theory and school learning. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston. Covington, M.V. & Omelich, C.L. (1979). Effort: The double-edged sword in school achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 71, 169-182. Covington, M.V. & Teel, K.M. (1996). Overcoming student failure: Changing motives and incentives for learning. Washington D.C. American Psychological Association. Crawford, L.W. (1993). Language and literacy learning in multicultural classrooms. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn and Bacon. Cummings, J. (1986). Empowering minority students: A framework for intervention. Harvard Educational Review, 56(1), 18-36.

26

Davis, John. (1989). Effective Schools, Organizational Culture, and Local Policy Initiatives. In Educational Policy For Effective Schools, edited by Mark Holmes, Keith Leithwood, and Donald Musella. New York: Teachers College Press. Deal, Terrence E. (1987). The Culture of Schools. In Leadership: Examining the Elusive, edited by Linda T. Sheive and Marian B. Schoenheit. Alexandria, Virginia: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. DeBruin-Parecki, Andrea; Teel, K. M., Covington, M. V. (1998). Addressing Achievement Motivation Among African-American Middle School Students Placed At Risk for School Failure: A Collaborative Attempt to Connect Theory to Practice. Teaching and Teacher Education: August. Deci, E., E.R. Vallerand, l.G. Pelletier, and R.M. Ryan. (Summer-Fall 1991). Motivation and Education: The Self-Determination. Educational Psychologist 26, 3-4: 325346. Delpit, L.D. (1988). The silenced dialogue: Power and pedagogy in educating other peoples children. Harvard Educational Review, 58, (3), 280-98. Delpit, L.D. (1992). Education in a multi-cultural society: Our futures greatest challenge. Journal of Negro Education, 61(3), 237-249. Delpit, L.D. (1995). Other peoples children: Conflict in the classroom. New York: New Press. Derman-Sparks, L., C. Tanaka Higa, and B. Sparks. (1980) Children, race and racism: How race awareness develops. Bulletin 11(3 & 4): 3-9. Diaz, C. ed. (1992) The next millennium: A multicultural imperative for education for the twenty-first century. Robert McClure NEA Mastery In Learning Consortium, NEA National Center for Innovation Series Editor. Washington D.C. Donaldson, K. B. (1994). Racism in U.S. schools: Assessing the impact of an antiracist multicultural arts curriculum on high school students in a peer education program. University of Massachusetts, Amherst: unpublished dissertation. Dweck, C. & Bempechat, J. (1983). Childrens theories of intelligence: Consequences for learning. In S. G. Paris, G. M. Olsen, & H. W. Stevenson (Eds.) Learning and motivation in the classroom. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum. Dweck, C.S.; & Leggett, E.L. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95, 256-273. Eccles (Parsons), J.; C. Midgely; and T.F. Adler. (1984). Grade-Related Changes in the

27

School Environment: Effects on Achievement Motivation. In Advances in Motivation and Achievement, Vol. 3: The Development of Achievement Motivation, edited by John G. Nicholls. Greenwich, Connecticut: JAI Press. Eccles, J.S., & Midgley, C. (1989). Stage/environment fit: Developmentally appropriate classrooms for early adolescents. In R.E. Ames & C. Ames (Eds.), Research on Motivation in Education. (Vol.3, pp. 139-186). New York: Academic. Eccles, J. S.; Wigfield, A. & Schiefele, U. (1998). Motivation to succeed. In Handbook of Child Development, Vol. 3, 1017-1095. Edwards, R. (1986). Characteristics of effective schools. In The School Achievement of Minority Children: News Perspectives. Edited by Elrich Neisser. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Elliot, A.J.; & Church, M. A. (1997). A hierarchical model of approach and avoidance achievement motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72, 218232. Feeney, S., D. Christensen, and E. Maravick. (1991) Who am I in the lives of children. Macmillan Publishing Company, New York, 1991. Fordham, S. (1988). Racelessness as a factor in black students school success: Pragmatic strategy or Pyrrhic victory? Harvard Educational Review 58(1): 54-84. Fordham, S. & Ogbu, J.U. (1986). Black students school success: Coping with the burden of acting white. The Urban Review, 18,(3), 176-206. Friedel, Jeanne; Ludmila Hruda, & Carol Midgley. (2001). When Children Limit Their Own Learning: The Relation Between Perceived Parent Achievement Goals and Childrens Use of Avoidance Behaviors. University of Michigan. Frome, P. M., Eccles, J. S. (1998). Parents influence on childrens achievement-related perceptions. Journal of personality and social psychology, 74, 435-452. Gardner, H. (1993). Multiple intelligences: The theory and practice. New York: Basic Books. Gardner, H., and T. Hatch. (1990). Multiple intelligences go to school: Educational implications of the theory of multiple intelligences. Educational Researcher 18(8): 4-10. Garibaldi, A. (1989). Educating black male youth. New Orleans: Public Schools. Gay, G. (1993). Building cultural bridges. Educational and Urban Society 25(3): 285299.

28

Gay, G. (1992). Effective teaching practices for multicultural classrooms. In Multicultural education for the twenty-first century, Edited by Carlos Diaz. Washington D.C. NEA National Center for Innovation. Giroux, H. (1984). Public philosophy and the crisis of education. Harvard Educational Review, 54(2), 186-195. Glaser, B. &Strauss, A. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. New York: Aldine De Gruyter. Good, T.L., and J.E. Brophy. (1987). Looking in Classrooms. New York: Harper & Row. Graham, S. (1988). Can attribution theory tell us something about motivation in Blacks? Education Psychologist, 23(1), 3-21. Graham, S. (1990). Communicating low ability in the classroom: Bad things good teachers sometimes do. In S. Graham and V. Folkes (Eds.), Attribution Theory: Applications to Achievement, Mental Health, and Interpersonal Conflict (pp. 1736). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Graham, S. (1994). Motivation in African-Americans. Review of Educational Research, 64(1), 55-118. Grossnickle, Donald R. (1989) Helping Students Develop Self Motivation: A Sourcebook for Parents and Educators. Reston, Virginia: National Association of Secondary School Principals. Grotevant, H.S. (1998). Adolescent development in family contexts. In Handbook of Child Development, Vol. 3, 1097-1149. Guild, P. (1994). The culture/learning style connection. Educational Leadership 51(8): 16-21. Hale, J.E. (1994). Unbank the fire: Visions for the education of African-American children. Baltimore, MD.: John Hopkins University Press. Hale-Benson, J. (1986) Black children: Their roots, culture and learning styles, 2nd ed. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press. Haynes, N.M. & Comer, J. (1990). Helping black children succeed: The significance of some social factors. In K. Lomotey (Ed.), Going to school: The African-American experience (pp.103-112). Albany: State University of New York Press. Heath, S.B. (1983). Ways with words: Language, life, and work in communities and classrooms. New York: Cambridge University Press.

29

Heath, S.B. (1986). What no bedtime story means: Narrative skills at home and at school. In Schieffelin, B. B. & Ochs, E. (Eds.), Language socialization across cultures (pp. 97-124). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Heyman, G., & Dweck, C., & Cain, K. (1992). Young childrens vulnerability to selfblame and helplessness: Relationship to beliefs about goodness. Child Development, 63, 401-415. Hilliard, A. (1976). Alternatives to IQ testing: An approach to the identification of gifted minority children. Report to the California State Department of Education. Hilliard, A. G., III. (1992). Behavioral style, culture, and teaching and learning. Journal of Negro Education 61(3): 370-377. Hixson, J. (1990). Multicultural issues in teacher education: Preparing teachers for new realities and challenges. Paper presented at the American Association of Colleges of Teacher Education Annual Conference, Chicago, Illinois. Hodgkinson, H.L. (1985). All one system: demographics in education, kindergarten through graduate school. Washington D.C. The Institute for Educational Leadership. Howard, G.R. (1993). Whites in multicultural education: Rethinking our role. Phi Delta Kappan 75(1): 36-41. Irvine, J. (1990). Black students and school failure: Policies, practices, and prescriptions. New York: Basic Books. Jencks, C., Smith, M., Acland, H., Bane, M.J., Cohen, D., Gintis, H., Heyns, B., & Michelson, S. (1972). Inequality: A reassessment of the effect of family and schooling in America. New York: Basic Books. Jensen, Eric. (1998) Teaching With the Brain in Mind. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. Alexandria, Virginia USA. Joseph, G.G (1987). Foundations of Eurocentrism in mathematics. Race and class 28(3): 13-28. Kaplan, A., & Midgley, C. (in press). The relationship between perceptions of classroom environment and early adolescents affect in school: The role of coping strategies. Learning and Individual Differences. Klug, Samuel. (1989). Leadership and Learning: A Measurement-Based Approach for Analyzing School Effectiveness and Developing Effective School Leaders. In Advances in Motivation and Achievement, Vol. 6: Motivation Enhancing

30

Environments, edited by Martin L. Maehr and Caol Ames. Greenwich, Connecticut: JAI Press. Kohn, A. (1993). Punished by Rewards: The Trouble with Gold Stars, Incentive Plan. As, Praise, and Other Bribes. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. Knapp, M.S., Shields, P.M., & Turnbull, P.M. (1992). Academic challenges for the children of poverty: Summary report. Washington D.C.: U.S. Department of Education. Kumar, Revathy & Ludmila Z. Hruda. (2001). What do I want to be when I grow up?: Role of parent and teacher support in enhancing students academic confidence and educational expectations. University of Michigan. Kunjufu, J. (1986). Countering the conspiracy to destroy black boys. Vol. II. Chicago, Illinois: African American Images. Kunjufu, J. (1990). Countering the conspiracy to destroy black boys. Vol. III. Chicago, Illinois: African American Images. Ladson-Billings, G. (1992). Culturally relevant teaching: The key to making multicultural education work. In C.A. Grant (Ed.), Research and multicultural education: From margins to the mainstream (pp. 106-121). London: The Falmer Press. Lomotey, K. (1990). Introduction. In K. Lomotey (Ed.), The dreamkeepers: Successful teachers of African-American children. San Francisco: Jossey Bass Publishers. Leithwood, K.A., and D.J. Montgomery. (1984). Patterns of Growth in Principal Effectiveness. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association. (New Orleans, Louisiana, April 23-27, 1984). Maehr, Martin L. (1991a). Changing the Schools: A Word to School Leaders about Enhancing Student Investment in Learning. Paper presented at the annual meeting American Educational Research Association (Chicago, Illinois, April, 1991). Maehr, M. L., & Midgley, C. (1991b). Enhancing student motivation: A schoolwide approach. Educational Psychologist, 26, 399-427. Marshall, H.H.; & Weinstein, R.S., (1986). Classroom context of student-perceived differential teacher treatment. Journal of Educational Psychology, 78,(6), 441453. Marzano, R., D. Pickering, D. Arredondo, G. Blackburn, R. Brandt, and C. Moffett.

31

(1992). Dimensions of Learning. Alexandria, Va.: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. McCoy, B., and G.S. Boutte. (1995) Excluding black males in school. Kappa Delta Pi Record. 31(4): 172-176. McIntosh, P. (1995) White privilege and male privilege: A personal account of coming to see correspondences through work in womens studies. In race, class, and gender: An anthology 2nd ed. Edited by M. L. Anderson and P. H. Collins. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Midgley, C. (1993). Motivation and middle level schools. In P.R. Pintrich & M.L. Maehr (Eds.), Advances in Motivation and Achievement, Vol. 8: Motivation in the Adolescent Years (pp. 219-276). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. Midgley, C., Kaplan, A., Middleton, M., Urdan, T., Maehr. M.L., Hicks, L., Anderman, E., & Roeser, R. W. (1998). Development and validation of scales assessing students achievement goal orientation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 23, 113-131. Midgley, C.; Kaplan, A, Middleton, M., Urdan, T., Maehr M. L., Hicks, L.c Anderman, E., & Roeser, R. W. (1998). Development and validation of scales assessing students achievement and goal orientation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 23, 113-131. Midgley, C., & Urdan, T. (2001). Academic self-handicapping and achievement goals: A further examination. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 26, 61-75.. Mineka, S., M. Cook, and S. Miller. (1984). Fear Conditioned with Escapable and Inescapable Shock: The Effects of a Feedback Stimulus. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes 10: 307-323. Nakamura, K. (1993). A Theory of Cerebral Learning Regulated by the Reward System. Biological Cybernetics 68, 6: 491-498. Nicholls, J. G. (1984) Achievement motivation: Conceptions of ability, subjective experience, task choice, and performance. Psychological Review, 91, 328-346. Nolen, S.B. (1988). Reasons for studying: Motivational orientations and study strategies. Cognition and Instruction, 5, 269-287. Oakes, J. (1985). Keeping track: How schools structure inequality. New Haven, Ct.: Yale University Press. Oei, T., and G. Lyon. (1996) In our own words: Asian American students give voice to the challenges of living in two cultures. Teaching Tolerance (5(2): 48-59.

32

Ogbu, J. & Matute-Bianchi, M. (1986). Understanding sociocultural factors: Knowledge, identity, and school adjustment. In Beyond language: Social and cultural factors in schooling language minority students (pp. 74-142). Los Angeles: State University Evaluation, Dissemination and Assessment Center. Ogbu, J. (1990). Overcoming racial barriers to equal access. In Access to knowledge: An agenda for our nations schools. Edited by John Goodlad and Pamela Keatind. New York: The College Board. Ossie, D. (1978). Escape to Freedom. New York, Viking Press. Parsons, J. E.; Adler, T. F., Kaezala, C. M. (1982). Socialization of achievement attitudes and beliefs: Parental influences. Child Development, 53, 310-321. Pate, G.S., (1992) Reducing prejudice in society: The role of schools. In Multicultural Education for the 21st. Century. Edited by Carlos Diaz. Washington, D.C.: NEA School Restructuring Series. Phillips, S.U. (1972). Participant structures and communicative competence: Warm Springs children in community and classroom. In Cazden, C.B., John, V.P., & Hymes, D. (Eds.), Functions of language in the classroom. (pp 370-394). New York: Teachers College Press. Raffini, James P. (1988). Student Apathy: The Protection of Self Worth. What Research Says to the Teacher. Washington, D.C.: National Education Association. Renchler, Ron. (1992) School Leadership and Student Motivation. ERIC Clearinghouse on Educational Management. Eugene, OR. Restak, R. (1979, 1988). The Brain. New York: Warner Books. Rosenholtz, S.J. (1979). The classroom equalizer. Teacher, 97, 78-79. Rosenholtz, S.J. & Simpson, C. (1984). The formation of ability conceptions: Developmental trend or social construction. Review of Educational Research, 54, 31-63. Ryan, A. M.; Pintrich, P.R., & Midgley, C. (in press). Avoiding seeking help in the classroom: Who and why? Educational Psychology Review. Ryan, A.M., Hicks, L., & Midgley, C. (1997). Social goals, academic goals, and avoiding seeking help in the classroom. Journal of Early Adolescence, 17(2), 5-14. Ryan, A. M.; Gheen, M. H., & Midgley, C. (1998). Why do some students avoid asking

33

for help? An examination of the interplay among students academic efficacy, teachers social-emotional role, and the classroom goal structure. Journal of Educational Psychology, 90, 528-535. Schlecty, P. (January 1994). Increasing Student Engagement. Missouri Leadership Academy. Schumacher, Donna. (1998). The Transition to Middle School. ERIC Digest. ERIC Clearinghouse on Elementary and Early Childhood Education. Champaign, IL. Shade, B.J. (1989) Culture, style, and the educative process. Springfield, Illinois: Charles Thomas, Publisher. Shade, B.J. (1994) Understanding the African-American learner. In E.R. Hollins, J.E. King & W.C. Hayman (Eds.), Teaching diverse populations: Forming a knowledge base. (pp. 175-189). New York: State University of New York Press. Smiley, P. A.; & Dweck, C. S. (1994). Individual differences in achievement goals among young children. Child Development, 65, 1723-1743. Sternberg, R.J., and T.I. Lubart. (1995). Defying the Crowd: Cultivating Creativity in a Culture of Conformity. New York: The Free Press. Stipek, D. (1984) The development of achievement motivation. In C. Ames and R. Ames (Eds.), Research on motivation in education. New York: Academic Press. Stipek, Deborah J. (1988). Motivation to Learn: From Theory to Practice. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. Urdan, T. (1997). Examining the relations among early adolescent students goals and friends orientation toward effort and achievement in school. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 22, 165-191. Thomas, J.W. (1980). Agency and achievement: Self-management and self-regard. Review of Educational Research, 50, 213-240. Verble, M. (1985). How to encourage self-discipline. Learning, 14, 40-43. Weiner, B. (1972). Theories of motivation: From mechanism to cognition. Chicago: Markham. Weiner, B. (1985). An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychological Review, 92(4), 548-573. Weinstein, R. S. (1984). Classroom factors affecting students self-evaluations: An interactional model. Review of Educational Research, 54(3), 301-325.

34

Weinstein, R. S. (1986). The teaching of reading and childrens awareness of teacher expectations. In T. Raphael (Ed.) The contexts of school-based literacy (pp. 233252). New York: Random House. Weinstein, R.S. (1991). Expectations and high school change: Teacher-researcher collaborations to prevent school failure. American Journal of Educational Psychology, 74, 678-692. Weinstein, R.S, Marshall, H.H. Brattesani, K. A., and Middlestadt, S.E. (1982). Student perceptions of differential teacher treatment in open and traditional classrooms. Journal of Educational Psychology, 74, 678-692.

35

You might also like

- Anger ManagementDocument12 pagesAnger Managementafridayben0253100% (1)

- The art of misdirection: controlling attentionDocument3 pagesThe art of misdirection: controlling attentionewrewrNo ratings yet

- My Reflections On ShamanismDocument2 pagesMy Reflections On ShamanismPetru GusetNo ratings yet

- Cooper Powerpoints (All) PDFDocument1,109 pagesCooper Powerpoints (All) PDFBeste Ongun Alkan100% (27)

- Assessing the Success of Assessment for Learning in UK SchoolsDocument16 pagesAssessing the Success of Assessment for Learning in UK SchoolsMontyBilly100% (1)

- Project Based Learning ProposalDocument1 pageProject Based Learning ProposalTom GillsonNo ratings yet

- Curing of ConcreteDocument7 pagesCuring of ConcreteIani BatilovNo ratings yet

- Curing of ConcreteDocument7 pagesCuring of ConcreteIani BatilovNo ratings yet

- Action ResearchDocument8 pagesAction Researchapi-567768018No ratings yet

- Final MCQ OBDocument43 pagesFinal MCQ OBYadnyesh Khot100% (2)

- Classroom TalkDocument8 pagesClassroom Talkapi-340721646No ratings yet

- What A Writer Needs Book ReviewDocument9 pagesWhat A Writer Needs Book Reviewapi-316834958No ratings yet

- Marzano Teacher Evaluation Model All 8 QuestionsDocument26 pagesMarzano Teacher Evaluation Model All 8 Questionskeila mercedes schoolNo ratings yet

- TeachingWorkshops PDFDocument4 pagesTeachingWorkshops PDFMartina BarešićNo ratings yet

- The Science Behind HeartbreakDocument76 pagesThe Science Behind HeartbreakgprasadatvuNo ratings yet

- Early Science Education – Goals and Process-Related Quality Criteria for Science TeachingFrom EverandEarly Science Education – Goals and Process-Related Quality Criteria for Science TeachingRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Content UnitDocument3 pagesContent Unitapi-351587400No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument2 pagesUntitledTamara Hutchinson100% (1)

- ArtifactsDocument45 pagesArtifactsapi-418341355100% (1)

- On Teacher Collaboration - The Art of StrengtheningDocument16 pagesOn Teacher Collaboration - The Art of StrengtheningDeirdre BaileyNo ratings yet

- rtl1 - Engagement With An Educational Issue FinalisedDocument10 pagesrtl1 - Engagement With An Educational Issue Finalisedapi-408480165No ratings yet

- Lightbody 2 EbookDocument87 pagesLightbody 2 EbookKamala100% (1)