Professional Documents

Culture Documents

When Do Corporate Ethics Come Into Play in The Case of Adhu

Uploaded by

Shresth KotishOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

When Do Corporate Ethics Come Into Play in The Case of Adhu

Uploaded by

Shresth KotishCopyright:

Available Formats

Q1>WHEN DO CORPORATE ETHICS COME INTO PLAY IN THE CASE OF SADHU ?

Q2>WHICH CORPORATE ETHICS COMES INTO PLAY? For McCoy (1997, p. 64), the lesson of the Sadhu is that without corporate support, the individual is lost. Says McCoy, In a complex corporate situation, the individual requires and deserves the support of the group. (p. 64) There is, I believe, a difference between the ad hoc group hiking to the mountain summit four disparate groups who happen to be on the mountain at the same time and a true group or team, an intentional organization. In McCoy's scenario, there is no leader. There are guides, professionals who know the mountain, but they are not leaders of the entire group. There are likely formal or informal leaders within each national team, but there is no single person recognized as the overarching leader. And, perhaps understandably, no one steps forward. They are travelers headed in the same direction, voyagers with the same destination, but their coalition is not a coalition; merely coincidently do they travel together that early morning. To judge them against a notion of corporate responsibility or leadership is heavy handed. Where we dealing with a corporate as in collective group, the situation would be different. We expect groups created intentionally be it a club, a team, a corporation, an organization, or a community to have shared values, to have a shared sense of purpose, and to have formal and informal leaders. As McCoy (1997) tells us, It is management's challenge to be sensitive to individual needs, to shape them, and to direct and focus them for the benefit of the group as a whole. (p. 64) It is not our role to change the values of a group, but then it is also not our role to remain a part of a group whose values are in conflict with our own. McCoy asks When do we take a stand? (p. 60) For him, this is the basic question of the case. Our own values, our own moral principles must align with the organization's values and moral principles. McCoy writes, We cannot quit our jobs over every ethical dilemma, but if we continually ignore our sense of values, who do we become? As a journalist asked at a recent conference on ethics, "Which ditch are we willing to die in?" For each of us, the answer is a bit different. How we act in response to that question defines better than anything else who we are, just as, in a collective sense, our acts define our institutions. In effect, the Sadhu is always there, ready to remind us of the tensions between our own goals and the claims of strangers. (p. 60) When we come upon a ditch we are willing to die in, it is time to dig in and attempt to change the values of the group. The question remains: how can we change the values of a group? Harter, Edwards, McClanahan, Hopson, and Carson-Stern (2004) suggest success in using feminist principles of organizing as a backdrop in changing values of individuals and groups. Barlow, Jordan, and Hendrix (2003) offer a focus on character as key in moral development of individuals within a group. Campbell and Dardis (2004) would join Barlow, Jordan, and Hendrix in relying on shared values as fundamental within any group. Humphreys, Weyant, and Sprague (2003) suggest leader behavior and follower commitment play a large role in organizational commitment, including adjusting values which drive choices. In short, there are a multitude of approaches a person can take. One key element in impacting the value structure of a group is the role the individual plays. A leader can approach a values discussion with more ease then a group member or subordinate. Key in any change attempt, however, is a need for the agent of change to act in alignment with the values. Actions and behaviors must align with values. When a leader or a group member's actions are not in alignment with stated values, their credibility becomes nil and their impact on positive change falls dramatically. This is, perhaps, the most important lesson for anyone who wants to take responsibility

to change the values of a group: let actions speak as loud as words.

In McCoy's (1997) parable, Stephen acts in alignment with his values, at least so far as he is physically able. For him, the ethical purpose, principle, and consequence is clear, and he works not only conversationally, but through action, to attempt to bring the group around to his way of thinking. When he realizes he will not change the group's value system, he does what he can for the Sadhu and then heads up the mountain, following his lifeline carried on the backs of Sherpas and porters. In the Parable of the Sadhu, McCoy (1997) offers up a tale which provides a purposely ambiguous story, allowing for ample discussion about the ethical decisions made and not made by the characters. (p. 60) Knowing one's greater purpose and role in life, aligning actions to a that purpose and moral principles, and performing actions which create the best positive consequences, are all important decision points in the Sadhu story. And, they are important in real life, also, providing a framework for each of us in our personal and corporate life.

You might also like

- Leadership, Motivation, Change: The Vision for Positive Leadership for the Black CommunityFrom EverandLeadership, Motivation, Change: The Vision for Positive Leadership for the Black CommunityNo ratings yet

- Virtue Ethics and the Parable of the SadhuDocument5 pagesVirtue Ethics and the Parable of the Sadhuhaseeb100% (1)

- Brave Together: Lead by Design, Spark Creativity, and Shape the Future with the Power of Co-CreationFrom EverandBrave Together: Lead by Design, Spark Creativity, and Shape the Future with the Power of Co-CreationNo ratings yet

- Reaction Paper 4Document2 pagesReaction Paper 4Joseph Castillo FernandezNo ratings yet

- What We Know About LeadershipDocument12 pagesWhat We Know About LeadershipDEVINA GURRIAHNo ratings yet

- What Is Public Narrative PDFDocument17 pagesWhat Is Public Narrative PDFNatasa PapakonstantinouNo ratings yet

- Parable of SadhuDocument2 pagesParable of SadhuTanya JoNo ratings yet

- Beliefs, Values and NormsDocument21 pagesBeliefs, Values and NormsJuzleeNo ratings yet

- The Psychology of LeadershipDocument9 pagesThe Psychology of Leadershipahm3d.shalaby230No ratings yet

- Cross CultureDocument6 pagesCross CultureBashar Abu HijlehNo ratings yet

- A Good LeaderDocument4 pagesA Good LeaderFar Han100% (1)

- Michi e 2005Document17 pagesMichi e 2005Maggý MöllerNo ratings yet

- 6 Ethical Communities WorksheetDocument4 pages6 Ethical Communities Worksheetapi-720954085No ratings yet

- Sample Bbus - Good Refernecs InsideDocument12 pagesSample Bbus - Good Refernecs Insideamlannag6No ratings yet

- Assignment 1 16110301 MGMT 242Document6 pagesAssignment 1 16110301 MGMT 242Hira TariqNo ratings yet

- Price-2003-The Ethics of Authentic TransformatDocument15 pagesPrice-2003-The Ethics of Authentic Transformatjmalagon5568No ratings yet

- Artifact 1 - Coletta L DDocument13 pagesArtifact 1 - Coletta L Dapi-315590722No ratings yet

- Parable of Sadhu - ExtractDocument3 pagesParable of Sadhu - ExtractTavleen KaurNo ratings yet

- Case 3-1 Parable of Sadhu 3EDocument6 pagesCase 3-1 Parable of Sadhu 3ERudy50% (2)

- Learning leadership lessons from Barack ObamaDocument4 pagesLearning leadership lessons from Barack ObamaMehedi HasanNo ratings yet

- Parable of SadhuDocument2 pagesParable of SadhuTanya JoNo ratings yet

- 1 Badaracca, Defining Moments (Brief Post)Document5 pages1 Badaracca, Defining Moments (Brief Post)Baljit GillNo ratings yet

- Gerwig 6 Ethical Communities WorksheetDocument4 pagesGerwig 6 Ethical Communities Worksheetapi-630131676No ratings yet

- 1P 2019 Social Studies Guide - The Edges of Society PDFDocument38 pages1P 2019 Social Studies Guide - The Edges of Society PDFRahul RanjanNo ratings yet

- Can Personality Be ChangedDocument5 pagesCan Personality Be ChangedIgui Malenab RamirezNo ratings yet

- Moral Leadership? Be Careful What You Wish For: Bert SpectorDocument9 pagesMoral Leadership? Be Careful What You Wish For: Bert SpectorOvidiu BocNo ratings yet

- Journal Review On The Parable of SadhuDocument3 pagesJournal Review On The Parable of SadhuAudrey Kristina MaypaNo ratings yet

- Montoye - Management of Care in HospitalDocument9 pagesMontoye - Management of Care in Hospitalmasmicko07No ratings yet

- Moral Identity Picture ScaleDocument84 pagesMoral Identity Picture ScaleNancy DrewNo ratings yet

- Aaron Feuerstein: A Case Study in Moral Intelligence: Nixon, Maureen M. South UniversityDocument16 pagesAaron Feuerstein: A Case Study in Moral Intelligence: Nixon, Maureen M. South UniversityPrecious Grace CaidoNo ratings yet

- Mccall 1986Document4 pagesMccall 1986Ivan FirmandaNo ratings yet

- OA - Exploring The Leadership That MattersDocument5 pagesOA - Exploring The Leadership That MattersJulia CamilleriNo ratings yet

- Coaching and MentoringDocument12 pagesCoaching and MentoringIon RusuNo ratings yet

- Leps 560 Module 7 AssignmentDocument5 pagesLeps 560 Module 7 Assignmentapi-480432527No ratings yet

- LayersOf HumanValuesInStrategyDocument8 pagesLayersOf HumanValuesInStrategylali62No ratings yet

- Lit Review Due 6 19 2020Document19 pagesLit Review Due 6 19 2020api-513882663No ratings yet

- Download Leaders Morality Prototypicality And Followers Reactions Valeria Amata Giannella full chapterDocument35 pagesDownload Leaders Morality Prototypicality And Followers Reactions Valeria Amata Giannella full chapterrandall.martin659100% (4)

- 5 Symbolic Frame WorksheetDocument3 pages5 Symbolic Frame Worksheetapi-688369167No ratings yet

- LA10 Group BehaviorDocument6 pagesLA10 Group BehaviorGJ TomawisNo ratings yet

- Download Prosocial Leadership Understanding The Development Of Prosocial Behavior Within Leaders And Their Organizational Settings 1St Edition Timothy Ewest Auth all chapterDocument68 pagesDownload Prosocial Leadership Understanding The Development Of Prosocial Behavior Within Leaders And Their Organizational Settings 1St Edition Timothy Ewest Auth all chapterpatricia.marquardt574100% (2)

- The AnatomyDocument24 pagesThe AnatomymahinayzachlouisNo ratings yet

- Answer The Following Questions Based On Your Reading and Research in Approximately 650 WordsDocument3 pagesAnswer The Following Questions Based On Your Reading and Research in Approximately 650 WordsFreersguides RunescapeNo ratings yet

- Quantum Leadership PrinciplesDocument9 pagesQuantum Leadership PrinciplesEdukarista FoundationNo ratings yet

- Drescoll and Mckee, 2007Document13 pagesDrescoll and Mckee, 2007Abdul SamiNo ratings yet

- Learning Within GroupsDocument10 pagesLearning Within Groupssan printNo ratings yet

- Profession Spent Some Time Talking About The Importance of Values, andDocument13 pagesProfession Spent Some Time Talking About The Importance of Values, andrguha1986No ratings yet

- A Leader’s CSR Values Shape Company CultureDocument20 pagesA Leader’s CSR Values Shape Company CultureAndroids17No ratings yet

- Group formation and cohesion definedDocument26 pagesGroup formation and cohesion definedMuhammad UmairNo ratings yet

- Values-Based Leadership: The Lighthouse of Leadership TheoryDocument9 pagesValues-Based Leadership: The Lighthouse of Leadership TheoryStacey CrawfordNo ratings yet

- AI for Positive ChangeDocument3 pagesAI for Positive ChangerdfaderaNo ratings yet

- Impact of Vedic Worldview andDocument13 pagesImpact of Vedic Worldview andRandy HoweNo ratings yet

- Organizational Studies Journal of Leadership &Document15 pagesOrganizational Studies Journal of Leadership &Ali SyedNo ratings yet

- Personal Leadership Statement Mueller FinalDocument9 pagesPersonal Leadership Statement Mueller Finalapi-339904897No ratings yet

- Values and Ethics: Bedrock of Our Profession Spent Some Time Talking About TheDocument14 pagesValues and Ethics: Bedrock of Our Profession Spent Some Time Talking About TheRashmi BadjatyaNo ratings yet

- Final PaperDocument8 pagesFinal Paperapi-251392528No ratings yet

- Rise and Decline of Charismatic Leadership - HouseDocument75 pagesRise and Decline of Charismatic Leadership - Housemsaqibraza93No ratings yet

- Article 3Document15 pagesArticle 3Malekit6No ratings yet

- LEADERSHIP RECONSTRUCTED: HOW LENS MATTERSDocument21 pagesLEADERSHIP RECONSTRUCTED: HOW LENS MATTERSManoj RNo ratings yet

- s1c - Ead 867 - Final Education Leadership Philosphy PaperDocument8 pagess1c - Ead 867 - Final Education Leadership Philosphy Paperapi-554976729No ratings yet

- KYNA R. MAPA 202050517 MODULE 1: What Is Mores, Ethos, and Value?Document6 pagesKYNA R. MAPA 202050517 MODULE 1: What Is Mores, Ethos, and Value?Kyna MapaNo ratings yet

- Payment ReceiptDocument1 pagePayment ReceiptShresth KotishNo ratings yet

- Aiats Jeemain Test-6Document18 pagesAiats Jeemain Test-6Shivendra AgarwalNo ratings yet

- History NTPCDocument2 pagesHistory NTPCShresth KotishNo ratings yet

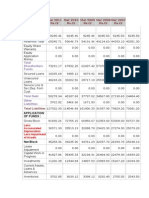

- A Synopsis ON: Comparison of The Profitability and Performance in The Financial Market of PGCIL With Its CompetitorsDocument8 pagesA Synopsis ON: Comparison of The Profitability and Performance in The Financial Market of PGCIL With Its CompetitorsShresth KotishNo ratings yet

- ReportDocument47 pagesReportShresth KotishNo ratings yet

- (224888313) Financial-Plan AnupamDocument23 pages(224888313) Financial-Plan AnupamShresth KotishNo ratings yet

- Financial Performance of Company Over Six YearsDocument2 pagesFinancial Performance of Company Over Six YearsShresth KotishNo ratings yet

- M A Strategy ArcelorMittal Part5Document2 pagesM A Strategy ArcelorMittal Part5Shresth KotishNo ratings yet

- M A Strategy ArcelorMittal Part2Document2 pagesM A Strategy ArcelorMittal Part2Shresth KotishNo ratings yet

- NHPC BSDocument2 pagesNHPC BSShresth KotishNo ratings yet

- Years Mar 2012 Rs - CR Mar 2011 Rs - CR Mar 2010 Rs - CR Mar 2009 Rs - CR Mar 2008 Rs - CRDocument1 pageYears Mar 2012 Rs - CR Mar 2011 Rs - CR Mar 2010 Rs - CR Mar 2009 Rs - CR Mar 2008 Rs - CRShresth KotishNo ratings yet

- Years Mar 2012 Rs - CR Mar 2011 Rs - CR Mar 2010 Rs - CR Mar 2009 Rs - CR Mar 2008 Rs - CRDocument1 pageYears Mar 2012 Rs - CR Mar 2011 Rs - CR Mar 2010 Rs - CR Mar 2009 Rs - CR Mar 2008 Rs - CRShresth KotishNo ratings yet

- Aakash Malhotra Model Financial Planning ReportsDocument18 pagesAakash Malhotra Model Financial Planning Reportssayedmaruf7866807No ratings yet

- Event Planning Business Plan SampleDocument19 pagesEvent Planning Business Plan Samplerajdanish88% (17)

- Prepared For: Mr. Mahendra DixitDocument31 pagesPrepared For: Mr. Mahendra DixitShresth KotishNo ratings yet

- Artha ShastraDocument1 pageArtha ShastraShresth KotishNo ratings yet

- Sample Family Financial Plan: Prepared ForDocument22 pagesSample Family Financial Plan: Prepared ForShresth KotishNo ratings yet

- Sample Financial PlanDocument34 pagesSample Financial PlanShresth KotishNo ratings yet

- Financial PlanniingDocument14 pagesFinancial PlanniingShresth KotishNo ratings yet

- Artha ShastraDocument1 pageArtha ShastraShresth KotishNo ratings yet

- Shareholders ReportDocument37 pagesShareholders ReportShresth KotishNo ratings yet

- Invicuts '14 CricketDocument1 pageInvicuts '14 CricketShresth KotishNo ratings yet

- Pgcil Sip Report JhaDocument72 pagesPgcil Sip Report JhaShresth KotishNo ratings yet

- Investment Planning For Retired PeopleDocument30 pagesInvestment Planning For Retired Peoplemoli21No ratings yet

- History NTPCDocument2 pagesHistory NTPCShresth KotishNo ratings yet

- Bfs Roundup Flip 87Document3 pagesBfs Roundup Flip 87Shresth KotishNo ratings yet

- Years Mar 2012 Rs - CR Mar 2011 Rs - CR Mar 2010 Rs - CR Mar 2009 Rs - CR Mar 2008 Rs - CRDocument1 pageYears Mar 2012 Rs - CR Mar 2011 Rs - CR Mar 2010 Rs - CR Mar 2009 Rs - CR Mar 2008 Rs - CRShresth KotishNo ratings yet

- Dividends DeclaredDocument1 pageDividends DeclaredShresth KotishNo ratings yet

- Vishleshan CaseDocument3 pagesVishleshan CaseHarish SatyaNo ratings yet

- Letter of AuthorizationDocument1 pageLetter of AuthorizationRamanuja SuriNo ratings yet

- Email:: Sri Hermuningsih, Desi Nur HayatiDocument15 pagesEmail:: Sri Hermuningsih, Desi Nur Hayatidafid slamet setianaNo ratings yet

- Intro to Org BehaviorDocument30 pagesIntro to Org BehaviorVidyasagar TiwariNo ratings yet

- Writing Position Papers: Write A Position Paper ToDocument2 pagesWriting Position Papers: Write A Position Paper ToMarida NasirNo ratings yet

- NSTP 2.3.2-Information Sheet TeamBuildingDocument2 pagesNSTP 2.3.2-Information Sheet TeamBuildingVeraniceNo ratings yet

- B. O'Connor, 'Hegel's Conceptions of Mediation'Document15 pagesB. O'Connor, 'Hegel's Conceptions of Mediation'Santiago de ArmaNo ratings yet

- Project CalendarDocument2 pagesProject Calendarapi-246393723No ratings yet

- Communication Is A Process of Transmitting Information From Origin Recipients Where The Information Is Required To Be UnderstoodDocument10 pagesCommunication Is A Process of Transmitting Information From Origin Recipients Where The Information Is Required To Be Understoodal_najmi83No ratings yet

- Take The 30 Day Feedback ChallengeDocument37 pagesTake The 30 Day Feedback ChallengeAjisafe Jerry T-moneyNo ratings yet

- GilgameshDocument2 pagesGilgameshTJ VandelNo ratings yet

- My Chapter 4Document71 pagesMy Chapter 4api-311624402No ratings yet

- Flowers at Work - Naran HealDocument3 pagesFlowers at Work - Naran Healkrasivaad100% (1)

- Bioecological Models: What Does This Mean For Parents?Document1 pageBioecological Models: What Does This Mean For Parents?woejozneyNo ratings yet

- Discourse AnalysisDocument48 pagesDiscourse AnalysisSawsan AlsaaidiNo ratings yet

- Activities - HTML: Co-Teaching Lesson PlanDocument2 pagesActivities - HTML: Co-Teaching Lesson Planapi-396243715No ratings yet

- Communication Skills Training OutlineDocument3 pagesCommunication Skills Training OutlineClaire Tatarian-NaccacheNo ratings yet

- Indl Difference - IGNOU Notes1Document4 pagesIndl Difference - IGNOU Notes1welcome2jungleNo ratings yet

- Principles of Teaching - Part 2Document25 pagesPrinciples of Teaching - Part 2Jomar M. TeofiloNo ratings yet

- Unit #4 Grade Topic Title Subject(s) Unit Guiding Questions: Energize Me 6Document8 pagesUnit #4 Grade Topic Title Subject(s) Unit Guiding Questions: Energize Me 6shaneearlNo ratings yet

- How Do Children Learn Language?Document3 pagesHow Do Children Learn Language?Siti Asmirah Baharan100% (1)

- Clifford 1988 Intro Pure ProductsDocument17 pagesClifford 1988 Intro Pure ProductsUlrich DemmerNo ratings yet

- SanggunianDocument3 pagesSanggunianRose Ann AlerNo ratings yet

- Jungle Week Lesson Plan 1Document5 pagesJungle Week Lesson Plan 1api-442532435No ratings yet

- Bag VowelsDocument2 pagesBag Vowelspushpi16No ratings yet

- Small Firm Internationalisation Unveiled Through PhenomenographyDocument22 pagesSmall Firm Internationalisation Unveiled Through PhenomenographyMeer SuperNo ratings yet

- Theories of PersonalityDocument4 pagesTheories of PersonalityKeshav JhaNo ratings yet

- Sally Mann - Immediate FamilyDocument82 pagesSally Mann - Immediate FamilyIon Popescu68% (25)

- The Adam Aircraft Work GroupDocument3 pagesThe Adam Aircraft Work GroupAllysa Barnedo50% (2)

- The Self As Cognitive ConstructDocument18 pagesThe Self As Cognitive ConstructMt. CarmelNo ratings yet

- Age Estimation Epiphiseal FusionDocument11 pagesAge Estimation Epiphiseal FusionbaduikeNo ratings yet

- Verb Noun Adjective Neg. Adjective AdverbDocument2 pagesVerb Noun Adjective Neg. Adjective AdverbKaunisMariaNo ratings yet

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeFrom EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeNo ratings yet

- No Bad Parts: Healing Trauma and Restoring Wholeness with the Internal Family Systems ModelFrom EverandNo Bad Parts: Healing Trauma and Restoring Wholeness with the Internal Family Systems ModelRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- The Millionaire Fastlane: Crack the Code to Wealth and Live Rich for a LifetimeFrom EverandThe Millionaire Fastlane: Crack the Code to Wealth and Live Rich for a LifetimeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Indistractable: How to Control Your Attention and Choose Your LifeFrom EverandIndistractable: How to Control Your Attention and Choose Your LifeRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (4)

- The Coaching Habit: Say Less, Ask More & Change the Way You Lead ForeverFrom EverandThe Coaching Habit: Say Less, Ask More & Change the Way You Lead ForeverRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (186)

- Uptime: A Practical Guide to Personal Productivity and WellbeingFrom EverandUptime: A Practical Guide to Personal Productivity and WellbeingNo ratings yet

- Summary of Atomic Habits: An Easy and Proven Way to Build Good Habits and Break Bad Ones by James ClearFrom EverandSummary of Atomic Habits: An Easy and Proven Way to Build Good Habits and Break Bad Ones by James ClearRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (557)

- The 5 Second Rule: Transform your Life, Work, and Confidence with Everyday CourageFrom EverandThe 5 Second Rule: Transform your Life, Work, and Confidence with Everyday CourageRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (7)

- Eat That Frog!: 21 Great Ways to Stop Procrastinating and Get More Done in Less TimeFrom EverandEat That Frog!: 21 Great Ways to Stop Procrastinating and Get More Done in Less TimeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3223)

- Summary: The 5AM Club: Own Your Morning. Elevate Your Life. by Robin Sharma: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: The 5AM Club: Own Your Morning. Elevate Your Life. by Robin Sharma: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (22)

- The One Thing: The Surprisingly Simple Truth Behind Extraordinary ResultsFrom EverandThe One Thing: The Surprisingly Simple Truth Behind Extraordinary ResultsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (708)

- Own Your Past Change Your Future: A Not-So-Complicated Approach to Relationships, Mental Health & WellnessFrom EverandOwn Your Past Change Your Future: A Not-So-Complicated Approach to Relationships, Mental Health & WellnessRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (85)

- Think Faster, Talk Smarter: How to Speak Successfully When You're Put on the SpotFrom EverandThink Faster, Talk Smarter: How to Speak Successfully When You're Put on the SpotRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Get to the Point!: Sharpen Your Message and Make Your Words MatterFrom EverandGet to the Point!: Sharpen Your Message and Make Your Words MatterRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (280)

- Quantum Success: 7 Essential Laws for a Thriving, Joyful, and Prosperous Relationship with Work and MoneyFrom EverandQuantum Success: 7 Essential Laws for a Thriving, Joyful, and Prosperous Relationship with Work and MoneyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (38)

- Summary: Hidden Potential: The Science of Achieving Greater Things By Adam Grant: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: Hidden Potential: The Science of Achieving Greater Things By Adam Grant: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (15)

- The High 5 Habit: Take Control of Your Life with One Simple HabitFrom EverandThe High 5 Habit: Take Control of Your Life with One Simple HabitRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Summary of Steven Bartlett's The Diary of a CEOFrom EverandSummary of Steven Bartlett's The Diary of a CEORating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- How to Be Better at Almost Everything: Learn Anything Quickly, Stack Your Skills, DominateFrom EverandHow to Be Better at Almost Everything: Learn Anything Quickly, Stack Your Skills, DominateRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (856)

- Think Faster, Talk Smarter: How to Speak Successfully When You're Put on the SpotFrom EverandThink Faster, Talk Smarter: How to Speak Successfully When You're Put on the SpotRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (55)

- Growth Mindset: 7 Secrets to Destroy Your Fixed Mindset and Tap into Your Psychology of Success with Self Discipline, Emotional Intelligence and Self ConfidenceFrom EverandGrowth Mindset: 7 Secrets to Destroy Your Fixed Mindset and Tap into Your Psychology of Success with Self Discipline, Emotional Intelligence and Self ConfidenceRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (561)

- Follow The Leader: A Collection Of The Best Lectures On LeadershipFrom EverandFollow The Leader: A Collection Of The Best Lectures On LeadershipRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (122)

- Seeing What Others Don't: The Remarkable Ways We Gain InsightsFrom EverandSeeing What Others Don't: The Remarkable Ways We Gain InsightsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (288)

- The Secret of The Science of Getting Rich: Change Your Beliefs About Success and Money to Create The Life You WantFrom EverandThe Secret of The Science of Getting Rich: Change Your Beliefs About Success and Money to Create The Life You WantRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (34)

- A Happy Pocket Full of Money: Your Quantum Leap Into The Understanding, Having And Enjoying Of Immense Abundance And HappinessFrom EverandA Happy Pocket Full of Money: Your Quantum Leap Into The Understanding, Having And Enjoying Of Immense Abundance And HappinessRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (158)

- Brain Rules (Updated and Expanded): 12 Principles for Surviving and Thriving at Work, Home, and SchoolFrom EverandBrain Rules (Updated and Expanded): 12 Principles for Surviving and Thriving at Work, Home, and SchoolRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (702)