Professional Documents

Culture Documents

16258232

Uploaded by

Naila Yulia WOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

16258232

Uploaded by

Naila Yulia WCopyright:

Available Formats

I S S U E S A N D IN N O V A T I O N S IN N U R S I N G P R A C T I C E

Pressure ulcers: implementation of evidence-based nursing practice

Heather F. Clarke

PhD RN

Principal, Health & Nursing Policy, Research & Evaluation Consulting, Vancouver, BC, Canada

Chris Bradley

PhD

Retired, Vancouver Coastal Health Authority, Vancouver Hospital, Vancouver, BC, Canada

Sandra Whytock

MSN RN GNC(c) NCA

Clinical Nurse Specialist, Elder Care Program, Providence Health Care, Vancouver, BC, Canada

Shannon Handeld

Vancouver, BC, Canada

BSN RN CWOCN

Implementation Lead, Pixalere Wound Care Management Project, Vancouver Coastal Health Authority, Vancouver Hospital,

Rena van der Wal

MN RN

Professional Practice Director for Nursing and Allied Health, Vancouver Acute, Vancouver Coastal Health Authority, Vancouver Hospital, Vancouver, BC, Canada

Sharon Gundry

MN RN

Project Manager, Fraser Health Authority, Fraser North, Surrey, BC, Canada

Accepted for publication 7 May 2004

Correspondence: Heather F. Clarke, Health & Nursing Policy, Research & Evaluation Consulting, 1575 Trafalgar Street, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6K 3R4. E-mail: heather.clarke@shaw.ca

CLARKE H.F., BRADLEY C., WHYTOCK S., HANDFIELD S., VAN DER WAL R. & G U N D R Y S . ( 2 0 0 5 ) Journal of Advanced Nursing 49(6), 578590 Pressure ulcers: implementation of evidence-based nursing practice Aims. A 2-year project was carried out to evaluate the use of multi-component, computer-assisted strategies for implementing clinical practice guidelines. This paper describes the implementation of the project and lessons learned. The evaluation and outcomes of implementing clinical practice guidelines to prevent and treat pressure ulcers will be reported in a separate paper. Background. The prevalence and incidence rates of pressure ulcers, coupled with the cost of treatment, constitute a substantial burden for our health care system. It is estimated that treating a pressure ulcer can increase nursing time up to 50%, and that treatment costs per ulcer can range from US$10,000 to $86,000, with median costs of $27,000. Although evidence-based guidelines for prevention and optimum treatment of pressure ulcers have been developed, there is little empirical evidence about the effectiveness of implementation strategies. Method. The study was conducted across the continuum of care (primary, secondary and tertiary) in a Canadian urban Health Region involving seven health care organizations (acute, home and extended care). Trained surveyors (Registered Nurses) determined the prevalence and incidence of pressure ulcers among patients in these organizations. The use of a computerized decisionsupport system assisted staff to select optimal, evidence-based care strategies, record information and analyse individual and aggregate data.

578

2005 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Issues and innovations in nursing practice

Pressure ulcers

Results. Evaluation indicated an increase in knowledge relating to pressure ulcer prevention, treatment strategies, resources required, and the role of the interdisciplinary team. Lack of visible senior nurse leadership; time required to acquire computer skills and to implement new guidelines; and difculties with the computer system were identied as barriers. Conclusions. There is a need for a comprehensive, supported and sustained approach to implementation of evidence-based practice for pressure ulcer prevention and treatment, greater understanding of organization-specic barriers, and mechanisms for addressing the barriers. Keywords: nursing, evidence-based practice, guidelines, implementation, pressure ulcers

Introduction

Pressure ulcers, which are lesions caused by unrelieved pressure resulting in damage to underlying tissues, persist as a major health care problem [Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR) 1992]. They are costly in terms of health care costs, lost wages, and decreased productivity, as well as human suffering. As the population ages and the acuteness of illness of patients receiving care increases, it is expected that the prevalence of pressure ulcers will continue to rise (Alterescu 1989, AHCPR 1994). Evidence-based pressure ulcer prevention and treatment guidelines have been available for over a decade, but are frequently ignored in clinical practice. Promoting the use of clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) throughout multiple organizations within an integrated health care system is more complex than doing so within an individual organization. While anecdotal reports have described complex challenges associated with implementation of guidelines (Davis & Taylor-Vaisey 1997, Dobbins et al. 1998, Ferlie et al. 2000), there is little empirical evidence about the effectiveness of large-scale CPG implementation across and within organizations. Challenges include quality of the guidelines, characteristics of health care professional, characteristics of practice settings, incentives, regulation and patient factors. Implementation strategies must overcome these challenges by

Table 1 Pressure ulcer prevalence rates

understanding the forces and variables inuencing practice and by using methods that are practice- and communitybased rather than didactic (Davis & Taylor-Vaisey 1997, Dopson et al. 2001).

Background

Pressure ulcers: the problem

Pressure ulcer prevalence and incidence studies document the magnitude of the problem, and can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions aimed at prevention and/or treatment. In 1994, the US-based Agency for Health Care Policy and Research reported the prevalence and incidence in various settings (AHCPR 1994) as nursing homes prevalence 2423%, with similar incidence; home health care prevalence 129% and annual incidence 43%; and acute care facilities prevalence 35295%, with similar incidence. The results of a prevalence study conducted at a large Canadian teaching hospital (Harrison et al. 1996) revealed prevalence rates similar to those reported in the US and in another Canadian study (Bradley & van der Wal 1995) (Table 1). These rates are unacceptable, given the demonstrated effectiveness of intervention programmes (Table 2).

Author Harrison et al. (1996)* Bankert et al. (1996) Gawron (1994) Meehan (1994) Foster et al. (1992)*

Facility type Acute care 42 hospitals Acute care 117 hospitals Hospitals three teaching, one community, two long-term care and community health care agencies two Multiple hospitals

Prevalence (%) 297 12 12 111 257

Meehan (1990) *Canadian study.

92

2005 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Journal of Advanced Nursing, 49(6), 578590

579

H.F. Clarke et al. Table 2 Prevalence rates before and after implementation of pressure ulcer intervention programmes

Author Sachorak & Drew (1998) Hansen et al. (1996) Suntken et al. (1996) Hunter et al. (1995) Regan et al. (1995) Burd et al. (1994)

Facility Acute care/community Home care Skilled care Rehabilitation Nursing home Skilled nursing home

Before (%) 17 19 21 25 24 28

After (%) 3 6 2 10 0 17

% Decrease 82 68 90 60 100 39

These high prevalence and incidence rates, coupled with the cost of treatment, constitute a substantial burden on health care systems. It is estimated that a pressure ulcer can increase nursing time up to 50%, and treatment costs per ulcer can range from US$10,000 to $86,000, with median costs of $27,000 (Allman et al. 1986, Greenberg et al. 1990). Although there has been extensive research into the prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers, limitations in research design have made it difcult to compare results among studies and to draw denitive conclusions (Bradley & van der Wal 1995). The range of results reported in prevalence studies is due, in part, to under-reporting, differing sample sizes, insufcient control of data acquisition, and the use of different pressure ulcer classication systems (Bradley & van der Wal 1995). Decreasing the prevalence and incidence of pressure ulcers requires identication of patients at risk, followed by provision of the best prevention and treatment possible. Research has shown that pressure ulcers can be prevented or treated more successfully across the care continuum when evidence-based care is provided (Bankert et al. 1996). The mere existence of CPGs does not, however, ensure better outcomes. They must be successfully implemented a process relying on many factors, including effective education; willingness to change clinical practice; availability of resources, appropriate personnel, equipment; supplies and administrative support. Implementation must be a priority for both the organization and the individuals providing care. Implementation of CPGs across the care continuum (primary, secondary and tertiary care in acute, home and extended care settings) presents additional challenges, including the development of communication strategies to ensure inter-agency collaboration and consistency of care.

range of evidence, including research ndings, quality improvement, and pathophysiological data and standards with practice that allow for nurses expertise and patient preferences (Mulhall 1998, Goode & Piedalue 1999). To assist nurses to meet the challenges of implementing evidencebased practice, research utilization models (e.g. Clarke 1995, Stetler 2001) and resources (e.g. Evidence Based Nursing Journal, knowledge synthesis reports, CPGs, etc.) have been developed. An integrated decision-making framework developed and tested by Clarke (1995) is comprised of four phases: articulation denition of the problem and location of research and other evidence; evaluation critical review of evidence for scientic merit and clinical signicance; comparison of evidence to the practice setting (patient population, organization, etc.); and application decision on whether or not to change practice, and if so, denition of implementation strategies and evaluation plans. Application of this framework requires partnerships among nurses with clinical expertise, research experience, and administrative responsibilities. Each phase requires particular nurses to be involved, decisions to be made, and resources to be accessed. The framework can be modied to make it relevant to both staff needs and organizational structure. It must be emphasized, however, that regardless of using theoretical foundations, implementation frameworks and tools, evidence-based practice is not a straightforward or simple linear process. The complexity of interacting variables, such as those related to empirical evidence, personal characteristics, organizational factors, and relationships within and among stakeholders, make for a messy, dynamic, and uid process (Dopson et al. 2002).

Evidence-based practice

When health care practice is evidence-based, i.e. practice integrates research evidence with clinical expertise and patient values, practice improves, resulting in better outcomes for patients, their families and the health care system (Heater et al. 1988, Sackett et al. 2000). Evidence-based nursing (EBN) has been dened as care incorporating a broad

580

Clinical practice guidelines

Clinical practice guidelines are designed to assist practitioners to integrate research ndings and expert knowledge within health care settings. They are based on explicit, science-based methodology and expert clinical judgement (AHCPR 1994), with the goal of reducing inappropriate variation in practice

2005 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Journal of Advanced Nursing, 49(6), 578590

Issues and innovations in nursing practice

Pressure ulcers

and promoting evidence-based health care (Davis & TaylorVaisey 1997, Thomas et al. 1999). Guidelines may be modied to t the circumstances or requirements of a specic agency through assessment of the practice environment, analysis of specic recommendations, development of strategies for implementation and evaluation of strategy interventions (Foster et al. 1992, Bradley & van der Wal 1995). Large-scale implementation of CPGs requires a systematic, planned implementation approach, incorporating input from those responsible for CPG use (Clarke 1995, Rogers 1995a,b, Stetler 2001). Although implementation models have been developed, there is little published on the effectiveness of their application in practice settings. Operational detail on dissemination and implementation strategies supporting evidence-based practice in nursing is lacking (Clarke 1999).

Behaviour change

To advance evidence-based decision-making and practice, effective dissemination and uptake of research ndings are key issues (Lomas 1993a, Tenove 1999). Within EBN practice models, research information must be actively disseminated in a synthesized form and carefully implemented at a local level to enable practitioners to apply the evidence to patient care (Lomas 1993b, Orlandi 1996). Dissemination includes education, regulation, public pressure, and social inuence from colleagues (Lomas 1993b). Dobbins et al. (1998) emphasized the importance of organizational infrastructure to promote effective research transfer and use, and concluded that one-to-one education, audit and feedback, and use of opinion leaders are effective dissemination strategies. When these are combined with other strategies, such as written materials, educational meetings, clinical reminders and mentoring, there is signicant potential for changing clinical behaviour and improving compliance with CPGs (Thomson OBrien et al. 2001). Important theories contributing to understanding the process of knowledge transfer into practice include those focusing on diffusion of innovations, social marketing theory and adult learning theory (Bandura 1986, Lomas 1993a, Rogers 1995a,b). Rogers (1995a)) found that individuals, including nurses, go through a mental innovation-decision process of ve stages (1) from knowledge of the innovation; (2) to forming an attitude toward the innovation (persuasion); (3) to a decision to adopt or reject the innovation; (4) to implementation of the new idea; and (5) to conrmation of this decision. Based on a review of approaches to diffusion and adoption of technology, Romano (1990) identied ve factors affecting the rate of moving through Rogers stages:

relative advantage degree to which an innovation is perceived as better than the idea it supersedes; compatibility degree to which an innovation is perceived as being consistent with existing values, experiences and needs of potential adopters; complexity degree to which an innovation is perceived as difcult to understand and use; trialability availability for the innovation to be tested; and observability degree to which the results are visible to others. Innovations perceived as having greater relative advantage, compatibility, trialability, observability, and less complexity will be adopted more rapidly than other innovations (Rogers 2002). Adult learning theory emphasizes the need to build on personal motivation to achieve sustained behavioural change (Bandura 1986), with educational strategies that predispose practitioners to change and reinforce change that has occurred (Lomas 1993b). Social inuence strategies focus on social norms, peer acceptance and habit as motivators for any behavioural change.

Computer-based decision support

Computer-based decision support systems have been proposed as one means of facilitating implementation of CPGs given their potential for altering, interpreting, assisting, critiquing and managing chronic conditions (Braden et al. 1997a). Zielstorff et al. (1997) reported positive user feedback and ratings of a computerized decision support system related to pressure ulcer prevention. The Wound and Skin Intelligence System (WSIS ConvaTec, Skillman, New Jersey, USA) a decision support system was designed to assess pressure ulcer risk and guide preventive intervention consistent with the AHCPR prevention and treatment of pressure ulcer CPGs (Braden et al. 1997a). In addition, it gives audit and feedback information considered to be effective in improving the practice of health care professionals (Thomson OBrien et al. 2003).

The study

A 2-year project was carried out to evaluate the use of multi-component, computer-assisted strategies for implementing CPGs. The basis of evidence-based practice was the AHCPR (1992, 1994) CPGs and recommendations for the prediction, prevention, and management of pressure ulcers. For our study, the basis of evidence-based practice was the AHCPR (1992, 1994) CPGs and recommendations

581

2005 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Journal of Advanced Nursing, 49(6), 578590

H.F. Clarke et al.

for the prediction, prevention, and management of pressure ulcers.

outlined in Table 3 and demonstrate variance within the Region a requirement for evaluating EBP implementation strategies.

Study objectives

The study objectives were to: assess, select, and implement strategies for implementing CPGs across the continuum of care; evaluate the effectiveness of the CPG implementation strategies; compare the prevalence and incidence of pressure ulcers before and after implementation of CPGs; identify factors that facilitate or impede implementation; and assess RN perceptions of the effectiveness of the implementation of the programme. This paper describes the evidence-based implementation strategies used in the study, to discuss insights learned during the process, and to draw conclusions about implementing CPGs across the continuum of care in a Health Region.

Conceptual framework

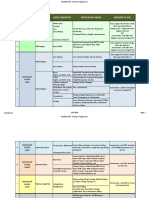

The implementation strategies and study phases were based on research related to Rogers ve phases of innovation adoption and Romanos ve factors inuencing the rate of adoption of innovations, as shown in Table 4. Banduras social learning theory and Clarkes research utilization framework informed the actual implementation throughout the study.

Study phases

The study was designed and implemented in six phases over a 2-year period. We will address objective 1 and phases 14 in this article and objectives 25 and phases 5 and 6 will be addressed in a second paper on evaluation of the CPG.

Participants

To initiate the study, a group of nurse experts in wound care and researchers sent information about the proposed study to senior nurse administrators of seven local provincial Health Regions. Admission criteria included administrative support for the study from each of the Regions participating facilities; evidence of previous research/study funding; and the presence of facilities in the Health Region that encompassed the care continuum. Of the ve respondents (i.e. Health Region senior nurse administrators), only one was from a Region that met all three criteria. This had an area of 10673 km2 and a population of almost 600,000 living in four semi-urban cities containing seven facilities (one acute, one extended care, four intermediate care, and home care). The characteristics of the seven facilities are

Phase 1: preparation for implementation

A Research Coordinator was hired to (1) facilitate implementation of the study, including adapting the pressure ulcer CPGs; (2) modify the computerized decision support software program; (3) select products; (4) develop an Interdisciplinary Wound Care Product Grid; and (5) select and develop educational materials. Adapting the pressure ulcer CPGs To ensure that the AHCPR pressure ulcer CPGs were consistent with evidence generated since 1994, a literature review was conducted and areas of new or controversial evidence identied. Local and international experts were consulted on each area of controversy. A panel consisting of a representative from each facility met to determine the CPG content

Type of facility Acute care Extended care* Intermediate care Intermediate care Intermediate care Intermediate care Home care

Total bed count 154 367 80 72 36 26 N/A

Primary wound care providers RNs RNs RNs RNs RNs RNs RNs

Available expertise ET, PT, OT, dietary PT, OT, dietary PT, dietary PT, dietary PT, dietary PT, dietary PT, nursing

Current pressure ulcer protocols Yes reviewed Yes reviewed Yes reviewed Yes No No No

Table 3 Characteristics of the project facilities

1 2 3 4

RN, Registered Nurse; ET, Enterostomal Therapist; PT, Physiotherapist; OT, Occupational Therapist. 582 2005 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Journal of Advanced Nursing, 49(6), 578590

Issues and innovations in nursing practice Table 4 Study framework phases, strategies and inuences Phases of study* Preparation 9 months (knowledge stage) Strategies Adapt CPGs Modify CDSS Select product Develop product grid Select training materials Experts (innovators) Mentors (early adopters) Training sessions staff Training sessions surveyors Enroll patients, obtain consent Incidence and prevalence surveys CPGs integrated in practice Care plans generated Experts and mentors troubleshoot and review practice Experts and mentors available Feedback from CDSS Incidence-prevalence studies Satisfaction measures Prepost training tests Meetings with senior nursesInuences

Pressure ulcers

Compatibility with existing values and experiences, relative advantage, complexity to understand, ability to be tested/observed Complexity of innovation, relative advantage Compatibility with values, experiences and learner needs Compatibility Ability to be tested/observed Ability to be observed, compatibility Complexity of innovation, relative advantage Complexity, compatibility Ability to be observed, advantage Ability to be tested Visibility of results Ability to be tested Relative advantage

Preimplementation 4 months (persuasion & decision stages)

Implementation 2 months (implementation stage)

Maintenance 10 months (conrmation stage) Evaluation 2 months development of recommendations

*Based on Rogers ve stages of adoption of innovations (1995a). Based on Romanos ve innovation characteristics that inuence the rate of moving through Rogers stages of adoption originally published in 1985 (1990). CPGs, Clinical Practice Guidelines; CDSS, Computerized Decision Support System Wound and Skin Intelligence System.

and format. The AHCPR (1992, 1994) guidelines were then modied and presented to an Interdisciplinary Region Working Group for nal review. The nalized interdisciplinary, patient-centred guidelines were then widely disseminated through the Health Region. Modifying the computerized decision support system The WSIS (renamed solutions for outcomes) was chosen as the computerized decision support system because it is consistent with the AHCPR CPG recommendations and assessment tools (Braden et al. 1997b). WSIS includes the Braden Scale (Bergstrom et al. 1987) (a standardized patient risk assessment tool) and the Pressure Sore Status Tool (PSST) (Bates-Jensen et al. 1992) (a pressure ulcer assessment tool). WSIS generates a plan of care based on patient information entered into the program. Defaults in the WSIS are designed to allow for case-by-case, context-specic alterations by a clinician (McNees 1999). A hard copy of the patients record is generated, while the program stores the original plan, alterations and the rationale for these, giving a basis for tracking and evaluation. Assessment, status changes and outcome tracking allow determinations of intervention

effects on single patients as well as patient groups. Prevalence and incidence estimates are available on an ongoing basis. The authors of the Braden Scale assisted with modifying the Braden Scale within the WSIS, ensuring clarity in the statements within the plans of care. Defaults were evaluated and, if necessary, modied to accommodate implementation recommendations across the continuum of care (e.g. consistency with the products selected by a Interagency Product Review Group). Selecting products and developing an interdisciplinary wound care product grid An Interagency Product Review Group of wound care experts, who had recently completed a literature review of wound care and prevention products, examined the AHCPRs CPGs for product recommendations and contacted several agencies in Canada to elicit their experience with products. Further consultation with local and international experts occurred when little information was available or controversial. The nal products chosen were integrated into an Interdisciplinary Decision Grid, Topical Treatment of Pressure Ulcers (Box 1) and into the computerized system.

583

2005 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Journal of Advanced Nursing, 49(6), 578590

H.F. Clarke et al. Box 1 Interdisciplinary decision grid topical treatment of pressure ulcers (framework and example of content provided on one double sided fact sheet) Side 1 Wound classication Black/necrotic phase (stage l unknown) Wound covered partially or completely by think leathery black, dry crust (eschar). May have no exudate. Pus, brous material and other cellular components may be present at wound edges. May have odour. Treatment objectives Product choices Key points

Debride eschar Reduce odour Exception: dry black leg ulcers or vascular or diabetic etiology

Clean with normal saline Hydrogel, e.g. Duoderm gel/Intrasite Gel

Change Opsite when it leaks or not intact Change treatment when eschar liquees (see treatments below)

Necrotic phase (yellow; stages 2, 3 and 4) Exudative phase (yellow; stages 2, 3 and 4) Granulation phase (red; stages 3 and 4) deep tissue damage Granulation phase (red; stage 2) supercial tissue damage Reddened phase (red; stage 1) related to pressure, shearing and friction Reddened phase (red; stage 1 or 2) related to moisture, e.g. incontinence, diaphoresis Description in each of four columns as per stage 1 above Side 2 Product highlights given for: Alldress; Duoderm gel; Duoderm CGF; ETE; Metipel; Mesalt/Mesalt ribbon; and Opsite A word about frequency of dressing changes Principles of an ideal dressing Contact information for Wound Care Resource Team member on the unit and a list of all other Resource Team members

Selecting and developing educational materials To identify the best education package, research team members reviewed and assessed videos and education materials from a variety of wound care companies. The criteria for selection of materials were: format; delivery time/method; audience suitability; reference to the AHCPR guidelines; inclusion of both prevention and treatment; use of generic product names; interdisciplinary content; cost and availability. The Johnson & Johnson self-learning package (Johnson & Johnson Worldwide 1995) was identied as meeting the requirements of this study.

Phase 2: preimplementation

Phase 2 strategies were: selecting and educating experts and mentors; developing implementation strategies; selecting and educating the surveyors; developing surveyors packages; enrolling patients and obtaining their written informed consent; conducting prevalence and incidence surveys; conrming ongoing inter-rater reliability; pretesting staff knowledge; and conducting staff education. In this paper, we will address strategies 1, 2 and 9 (see Table 4).

584

Selecting and educating mentors and experts practice support roles Decisions about the educational strategy were based on the conceptual framework and research on effective strategies for dissemination and implementation of research ndings. Key components of the educational strategy included development of two new roles mentor (facility-specic) and expert (regional resource) and use of the train the trainer model. Clinical leaders were key in implementing the CPGs. Although their role in these positions differed within each clinical setting, they were expected to coordinate implementation activities, mentor and expert nurses, and solve problematic clinical issues. The mentors were two nurses from each unit or facility who received education on risk determination, skin and wound assessment, pressure ulcer prevention and treatment, and the computerized system. The role of local mentors was to inform staff of the study goals and ongoing study activities, act as a resource to co-workers, and problem-solve unit-based issues. The two nurses selected from each unit or facility attended a one-day workshop on prevention and treatment of skin and wound problems, and a 4-hour training session on the computerized system. The role of experts was to provide support for the implementation of practice changes within the clinical settings. They were a resource for both mentors and staff and available for consultation on complex wounds.

2005 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Journal of Advanced Nursing, 49(6), 578590

Issues and innovations in nursing practice

Pressure ulcers

Regional experts included an elder care clinical specialist, enterostomal therapist, nurse clinicians in extended care, and a senior home care staff nurse. Experts received the same education as mentors, with additional education at a tertiary teaching hospital on management of complex wounds. Development of implementation strategies A one-day workshop, held for mentors and experts to review CPGs, provided an opportunity for discussion of their roles and expectations, and strategies for implementing the CPGs. Participants were grouped according to their care setting and worked together to develop implementation strategies specic to their areas. The strategies were submitted to the director/ coordinator/manager of each care setting for input and approval. Conducting staff education Staff nurses were given self-learning packages, videos (Braden 1988, Johnson & Johnson Worldwide 1995), and various materials related to risk assessments, prevention strategies, wound healing, and treatment of wounds. A tutorial version was provided in each clinical setting for 5 weeks prior to implementation to give an opportunity to practise and become comfortable with using the computer and software. Sample patient assessments were provided to allow nurses to generate mock plans of care. The Research Coordinator, members of the Research Team, mentors, and experts all gave support by conducting one-to-one educational sessions as opportunities arose.

Registered Nurse to generate and/or revise the plan of care, all members of the health care team were accountable for providing input to the plan. Reassessment Reassessment was done according to the individual facility guidelines if either the patients general condition or the condition of the pressure ulcer deteriorated. Prior to discharge or transfer, reassessment of the pressure ulcer was conducted and the plan of care updated. This latest plan of care, the most current ow sheet and a summary of the progress of the wound healing were sent to the appropriate person in the receiving agency. The onsite research team members addressed challenges encountered in achieving consistent implementation within routine care across the regions continuum of care. They had continuously to trouble-shoot problems relating to computers and software, staff attitudes, competencies and time, co-worker relationships, management and technical support, and study time frames.

Phase 4: maintenance

During the maintenance phase, it was expected that all nurses would conduct their clinical practice according to the CPGs, i.e. conduct regular risk assessment and skin and wound assessment according to the frequency established for each clinical setting (Table 5). They were also expected to enter the data into the computerized system, review the plan of care, generate an updated plan, and implement that plan. Documentation continued as per current standard practice specic to each agency. The unit/facility mentors were key to keeping the nursing staff on track with the changes to clinical practice and using the computer as a documentation and decision support tool. The experts were available to the mentors and the staff to assist with challenging assessments and ulcer treatments.

Phase 3: implementation

Once the staff education had been completed, the CPG interventions were implemented as part of routine patient care and included the following: conduct of routine risk, skin and wound assessment and generation of care plans; and reassessment at regular intervals if deterioration occurred, and upon discharge. Conduct of routine risk, skin and wound assessments and generation of care plans Routine assessments were conducted for all patients and a plan of care for prevention and/or treatment of ulcers developed for each. Nurses completed a Braden Scale skin assessment for all patients and a Pressure Sore Status Tool for those who were found to have pressure ulcers. This information was entered into the computerized program and a plan of care generated. While it was the responsibility of the

Ethical considerations

Ethics approval was obtained from the University Behavioural Research Ethics Board and the Ethics Committee of the Regions acute care hospital. It was a requirement of the University Ethics Board that all patients provide written informed consent for the prevalence and incidence surveys.

Data collection and analysis

As part of the study design, a staff questionnaire was delivered to all staff nurses, mentors and experts participating in the

585

2005 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Journal of Advanced Nursing, 49(6), 578590

H.F. Clarke et al. Table 5 Frequency of assessments at each level of care Acute care Frequency of Braden Scale assessment Within 24 hours of admission ICU*/CCU daily Acute care every Monday and Thursday Extended care Within 24 hours of admission Every week for the rst month and then quarterly If condition deteriorates, weekly until stable, then quarterly Weekly Within 24 hours of admission Daily with Braden 18 Home care On admission Braden >18, repeated only if condition. deteriorates Braden 18, weekly Intermediate care Within 24 hours of admission Every week for the rst month and then quarterly If condition deteriorates, weekly until stable, then quarterly Weekly On admission daily for those at risk, Braden 18 daily report reddened areas

PSST Skin assessment

Weekly Acute care Monday and Thursday with Braden 18

Weekly On bed-fast, chair-fast or high risk or patient/ care-giver report of skin breakdown Braden 18 daily

*ICU, Intensive Care Unit, CCU, Cardiac Care Unit, PSST, Pressure sore status tool.

study. Quantitative data were analysed for central tendency, while qualitative data were analysed for themes. Three major themes emerged relating to implementation: time taken to learn and to use the computer and decision support system; technological difculties associated with the computer system; and avoidance of the computer decision support system. Staff also identied implementation strategies that were most helpful to them. Analysis of the research teams meeting minutes, individual activity logs and discussions with senior nurse managers provided data for further identifying implementation challenges and strategies employed.

Findings

Nurses perceived that there were increased demands on their time due to learning new technology and computer skills, and updating the clinical practice knowledge required to implement the CPG program. Accessing the computer took longer than accessing patient health records and nurses often documented in both electronic and hard copies. In addition, they indicated that they had little time to consider potential wound problems, particularly in low and moderate risk patients. Frustrated with the computer system and discouraged because learning took more time than available, some staff avoided the computer altogether. In the acute care setting, some staff referred all wound care issues to the expert enterostomal therapist, rather than changing their practice to incorporate the CPG. Hospital and facility computer infrastructures were underresourced and frequently malfunctioned, making the program inaccessible. Computer system issues also resulted in loss of information. This inuenced staff perceptions of the effect586

iveness and credibility of the computerized decision support system. Implementation strategies identied as helpful included the risk assessment tools, plans of care, and wound care grid. Some staff perceived the plans of care generated by the computerized system as elementary and preferred to trust their own assessment skills, while mentors and experts perceived that they promoted consistency of information and introduction of new technology. Staff considered the use of education videos and education sessions for the mentors, follow-up instruction in a one-to-one setting, and problemsolving around specic clinical issues to be important educational strategies. Ongoing and consistent leadership support from administrators proved critical for successful implementation of the CPGs. The extent of administrative and clinical leader support and involvement varied by type of facility, as well as by position held within the institution. In home care, intermediate care and extended care, administrative leaders were perceived as highly supportive, facilitating activities that enabled the on-site coordinators, mentors, and experts to implement the clinical practice changes. In acute care, several changes in administrative leaders created a situation of limited familiarity with the study and a climate of uncertainty. Their support was less than optimal with limited attendance at information meetings, mixed response to unitspecic issues impeding implementation, and limited support for unit managers and staff. Increased communication between members of the interdisciplinary team; increased the likelihood of staff identifying issues related to the management of pressure ulcers; increased use of information relating to available resources; and

2005 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Journal of Advanced Nursing, 49(6), 578590

Issues and innovations in nursing practice

Pressure ulcers

improved consistency of care, documentation and outcomes were observed and noted. The research team had assumed that staff would be comfortable with the computerized system. This proved incorrect since a signicant amount of staff training was required. The cost of staff replacement during training/education created concern for managers because the resulting nancial outlay was not covered by the study budget. In summary, the major barriers to the implementation of CPGs were lack of consistent administrative leadership; time required to learn and to implement new guidelines; technological deciencies of the hospital computer system; and competencies related to learning the computerized decision support system. These challenges are consistent with recent literature on EBP implementation (Royle & Blythe 1998, Ferlie et al. 2000, Dopson et al. 2001, 2002, Meleskie & Wilson 2003).

in all settings, computer competencies of staff need to be considered. During implementation, none of these issues were totally resolved, leading to the need for recommendations. Because of the inequity of resources among facilities and limited resources within the region, it was recommended that policies and guidelines be established for sharing resources on an as-needed basis, including purchasing wound care products and expensive equipment. Within intermediate and home care settings, it was recommended that expertise be established for pressure ulcer assessment and management.

Health region recommendations

The following recommendations for the Health Region were generated in discussions with senior managers in the health facilities. Clinical Practice Guidelines for prevention and management of pressure ulcers, based on evidence and adapted to the practice environment, should be implemented across the entire Health Region. It was recommended that one senior nurse leader be responsible for the facilitation, implementation and maintenance of the CPGs and that an interdisciplinary steering group be established to address issues such as standardizing products, documentation, education and partnerships for sharing resources and expenses. To support regional implementation of evidence-based practice, the program responsible for quality management and the senior nurse leader should identify and implement practice support structures. These should include implementing a clinical professional practice model; articulating roles and expectations for all staff and managers; identifying a framework for integrating evidence-based clinical tools with practice; and providing opportunities and supports to assist staff participation in planning for implementation of evidence-based practice strategies in their areas. The results of this study, which was conceptualized, designed, funded and implemented in 1996, have been corroborated by more recently published studies, particularly ndings related to the infrastructure supports required for implementing evidencebased practice.

Discussion

Based on insights gained from implementing evidence-based CPGs across the continuum of care in a Health Region, a number of recommendations were made. The recommendations developed by the research team in consultation with senior nurse managers related to individual health care facilities and the Health Region as a whole.

Health care facilities recommendations

In general, it was recommended that all facilities continue to use the pressure ulcer CPGs and computer decision support system to facilitate evidence-based practice in nursing. In facilities such as acute care, where there was less successful implementation, barriers identied by unit managers, staff and research team, needed to be reviewed and resolved. These included clarication of roles and responsibilities of staff, unit managers and administrative leaders regarding implementation of evidence-based practice and identication of practice and documentation standards, especially in the area of risk assessment. It was also recommended that additional implementation strategies be considered that integrated evidence-based practice into standard practice (e.g. care maps). Identifying and addressing clinical (e.g. having access to an enterostomal therapist in all practice settings), equipment (e.g. having computers readily available in each setting), and nancial (e.g. having professional development time and specialized supplies relevant to the CPG recommendations) resource issues need to be done on a continuous basis with changing contexts of practice. Furthermore,

Conclusions

These study ndings conrm what is already known about implementing an innovation such as evidence-based practice. Although a responsibility of each nurse, evidence-based practice requires supportive professional practice environments that include leadership and commitment from nurse managers. Regional implementation of specic evidence-based

587

2005 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Journal of Advanced Nursing, 49(6), 578590

H.F. Clarke et al.

What is already known about this topic

Prevention and early treatment of pressure ulcers can be improved using evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Evidence-based practice is a responsibility of all nurses, since they are accountable for such practice to their patients, the public and their employers. Implementation of evidence-based practice using clinical practice guidelines is complex and needs to be addressed in a systematic and rigorous way.

Johnson and 3M. Finally, we acknowledge all members of the project team, whose contributions were essential to the projects success.

Author contributions

All listed authors have contributed directly to this study and this paper. HFC, CB, SW, and RW contributed to study conception and design. SW, SH, RW, and SG contributed to data collection. HFC, CB and RW contributed to data analysis. HFC, CB, SH and RW contributed to drafting of manuscript. HFC, SW, SH and RW contributed to critical revisions of manuscript for important intellectual content. CB contributed to statistical expertise. HFC and RW contributed to obtaining funding. SW, SH, RW and SG contributed to administration, technical or material support. SH, RW and SG contributed to supervision.

What this paper adds

The effectiveness of dissemination and implementation strategies for the uptake of evidence as clinical practice guidelines by nurses depend on nursing leadership and other system factors. It is feasible to develop consistent region-wide evidencebased practice. The challenges of introducing new technology to support nursing practice are related to change, time and computer skills.

References

Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (1992) Pressure Ulcers in Adults: Prediction and Prevention. AHCPR pub. no. 92 0047. US Department of Health and Human Services, Rockville, MD. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (1994) Treatment of Pressure Ulcers. AHCPR pub. no. 920652. US Department of Health and Human Services, Rockville, MD. Allman R.M., Laprade C.A., Noel L.B., Walker J.M., Moorer C.A., Dear M.R. & Smith C.R. (1986) Pressure ulcers among hospitalized patients. Annals of Internal Medicine 105(3), 337342. Alterescu V. (1989) The financial costs of inpatient pressure ulcers to an acute care facility. Decubitus 2(3), 1423. Bandura A. (1986) Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliff, NJ. Bankert K., Daughtridge S., Meehan M. & Colburn L. (1996) The application of collaborative benchmarking to the prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers. Advances in Wound Care 9(2), 2129. Bates-Jensen B.M., Vredevoe D.L. & Brecht M.L. (1992) Validity and reliability of the Pressure Sore Status Tool. Decubitus 5(6), 2028. Bergstrom N., Braden B.J., Laguzza A. & Holman V. (1987) The Braden Scale for predicting pressure sore risk. Nursing Research 36(4), 205210. Braden B. (1988) The Braden Scale (Video). University of Nebraska, Omaha, Nebraska. Braden B., Bergstrom N. & Mc Nees P. (1997a) The Braden System. In Nursing Informatics: The Impact of Nursing Knowledge on Health Care Informatics. Proceedings of NI97, Sixth Triennial International Congress of IMIA-NI, Nursing Informatics of International Medical Informatics Association 46. (Gerdin U., ed.), ISO Press, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 562. Braden B.J., Corritore C. & McNees M.P. (1997b) Computerized decision support systems: implications for practice. In Studies in Health Technology Information, 4 (Geudin U., ed.), ISO Press, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, pp. 300304.

practice is more complex than single setting implementation and needs systematic planning. Attending to the ve stages of innovation adoption and factors that affect progress through each stage is critical to success. The study contributes to knowledge of dissemination and implementation strategies that increase the likelihood of nurses uptake of evidence in the form of CPGs. However, the specic recommendations made for the health care facilities and Region require further research in other contexts, as well as research on strategies for overcoming difculties with technology and integrating evidence-based practice in everyday nursing practice for the long-term.

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge the supportive collaboration of the partnering organizations, their senior nurse leaders and staff in making this project possible. The advice of local, national and international experts ensured both clinical and research integrity and relevancy. The project was made possible with funding from the Vancouver Foundation/BC Medical Services Foundation, ConvaTec, KCI Medical Canada, Mo lnlycke Health Care, and Elder Health South Fraser Health Region and in-kind support from participating agencies, Johnson &

588

2005 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Journal of Advanced Nursing, 49(6), 578590

Issues and innovations in nursing practice Bradley C. & van der Wal R. (1995) Pressure Ulcer Prevalence Survey (Internal Report). Vancouver Hospital and Health Sciences Centre, Vancouver. Burd C., Olson B., Langemo D., Hunter S., Hanson D., Osowski K. & Sauvage T. (1994) Skin care strategies in a skilled nursing home. Journal of Gerontological Nursing 20(11), 2834. Clarke H.F. (1995) Research utilization: using research to improve the quality of nursing care. Nursing BC 27(5), 1922. Clarke H.F. (1999) Moving research utilization into the millennium. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research 31(1), 57. Davis D.A. & Taylor-Vaisey A. (1997) Translating guidelines into practice: a systematic review of theoretic concepts, practical experience and research evidence in the adoption of clinical practice guidelines. Canadian Medical Association Journal 157(4), 408416. Dobbins M., Ciliska D. & Mitchell A. (1998) Dissemination and Use of Research Evidence for Policy and Practice: A Framework for Developing, Implementing, and Evaluating Strategies. A report prepared for the Dissemination and Utilization Model Advisory Committee of the Canadian Nurses Association and Health Canada. Health Canada, Ottawa. Dopson S., Locock L., Chambers D. & Gabbay J. (2001) Implementation of evidence-based medicine: evaluation of the Promoting Action on Clinical effectiveness programme. Journal of Health Services & Research Policy 6(1), 2331. Dopson S., Fitzgerald L., Ferlie E., Gabbay J. & Lockock L. (2002) No magic targets! Changing clinical practice to become more evidence based. Health Care Management Review 27(3), 3547. Ferlie E., Fitzgerald L. & Wood M. (2000) Getting evidence into clinical practice: an organizational behaviour perspective. Journal of Health Services & Research Policy 5(2), 96102. Foster C., Frisch S., Denis N., Forler Y. & Jago M. (1992) Prevalence of pressure ulcers in Canadian institutions. Canadian Association of Enterostomal Therapists Journal 11(2), 2331. Gawron C.L. (1994) Risk factors for and prevalence of pressure ulcers among hospitalized patients. Journal of Wound/Ostomy/ Continence Nursing 21(6), 232240. Goode C.J. & Piedalue F. (1999) Evidence-based clinical practice. Journal of Nursing Administration 29(6), 1521. Greenberg A., Birkenstock G., Cotter D.J., Hamilton M.T. & Stefanil K. (1990) National Health Services and practice patterns survey rst year report on debutius ulcer incidence rates, treatment costs and Medicare payments. The Medical Technology and Practice Patterns Institute, Inc., Washington, DC. Hansen D., Langermo L., Olson B., Hunter S. & Burd C. (1996) Decreasing the prevalence of pressure ulcers using agency standards. Home Healthcare Nurse 14(7), 525531. Harrison M.B., Wells G., Fisher A. & Prince M. (1996) Practice guidelines for the predication and prevention of pressure ulcers: evaluating the evidence. Applied Nursing Research 9(1), 917. Heater B., Becker A. & Olson R. (1988) Nursing interventions and patient outcomes: a meta-analysis of studies. Nursing Research 37(38), 303307. Hunter S., Langemo D., Olson B., Hanson D., Cathcart-Silberberg T., Burd C. & Sauverg T. (1995) The effectiveness of skin care protocols for pressure ulcers. Rehabilitation Nursing 20(5), 250 255.

Pressure ulcers Johnson & Johnson Worldwide (1995) Professional Education & Services. Wound Management Education Series: 1. Effective Wound Care. 2. Wound Healing Process. 3. Wound Assessment. Johnson & Johnson Worldwide, Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Lomas J. (1993a) Diffusion, dissemination, and implementation: Who should do what? Annals of the New York Academy of Science 703, 226235. Lomas J. (1993b) Retailing research: Increasing the role of evidence in clinical services for childbirth. The Millbank Quarterly 71(3), 439475. McNees M.P. (1999) International systems to support improvement in healthcare. In Best Practices Series: Handbook of Healthcare Information Systems (Davidson P., ed.), Auerbach, London, UK, pp. 439450. Meehan M. (1990) Multi-Site pressure ulcer prevalence survey. Decubitus 3(4), 1417. Meehan M. (1994) National Pressure Ulcer Prevalence Survey. Advances in Nursing Care 7(3), 2738. Meleskie J. & Wilson K. (2003) Developing regional clinical pathways in rural health. Canadian Nurse 99(8), 2528. Mulhall A. (1998) Nursing, research, and the evidence. EvidenceBased Nursing 1(1), 46. Orlandi M.O. (1996) Health promotion technology transfer: Organizational perspectives. Canadian Journal of Public Health 87(2), S28S33. Regan M., Byers & Mayrovitz H. (1995) Efficacy of a comprehensive pressure ulcer prevention program in an extended care facility. Advances in Wound Care 8(3), 4955. Rogers E.M. (1995a) Diffusion of Innovations, 4th edn. The Free Press, New York. Rogers E.M. (1995b) Lessons for guidelines from the diffusion of innovations. Joint Commission Journal on Quality Improvement 21(7), 324328. Rogers E.M. (2002) Diffusion of preventive innovations. Addictive Behaviors 27(6), 989993. Romano C.A. (1990) Diffusion of technology innovation. Advances in Nursing Science 13(2), 1121. Royle J. & Blythe J. (1998) Promoting research utilization in nursing: The role of the individual, organization, and environment. Evidence-Based Nursing 1(3), 7172. Sachorak C. & Drew J. (1998) Use of a total quality management model to reduce pressure ulcer prevalence in the acute care setting. Journal of Would/Ostomy/Continence Nursing 25(2), 8892. Sackett D.L., Strauss S.E., Richardson W.S., Rosenberg W. & Haynes R.B. (2000) Evidence-Based Medicine: How to Practice and Teach EBM. Churchill Livingstone, London, UK. Stetler B. (2001) Updating the Stetler model of research utilization to facilitate evidence-based practice. Nursing Outlook 49(6), 272 279. Suntken G., Starr B., Ermer-Seltun J., Hopkins L. & Preftakes D. (1996) Implementation of a comprehensive skin care program across care settings using the SHCPR pressure ulcer prevention and treatment guidelines. Ostomy/Wound Management 42(2), 2032. Tenove S.C. (1999) Dissemination: current conversations and practices. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research 31(1), 9599. Thomas L.H., McColl E., Cullum N., Rousseau N. & Soutter J. (1999) Clinical guidelines in nursing, midwifery and the therapies: a systematic review. Journal of Advanced Nursing 30(1), 4050.

2005 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Journal of Advanced Nursing, 49(6), 578590

589

H.F. Clarke et al. Thomson OBrien M.A., Oxman A.D., Davis D.A., Haynes R.B., Freemantle N. & Harvey E.L. (2001) Educational outreach visits: effects of professional practice and health care outcomes (cochrane review). In Cochrane Library, Issue 3. Update Software, Oxford. Thomson OBrien M.A., Oxman A.D., Davis D.A., Haynes R.B., Freemantle N. & Harvey E.L. (2003) Audit and feedback. In Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 1. Update Software, Oxford. Zielstorff R.D., Estey G., Vickery A., Hamilton G., Fitzmaurice J.B. & Barrett G.O. (1997) Evaluation of a decision support system for pressure ulcer prevention and management: preliminary findings. Proceedings of the AMIA Fall Symposium 46, 248252.

590

2005 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Journal of Advanced Nursing, 49(6), 578590

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Oxigen Gen Container CMM 35-21-14Document151 pagesOxigen Gen Container CMM 35-21-14herrisutrisna100% (2)

- Evaluating Skin Care Problems in People With StomasDocument8 pagesEvaluating Skin Care Problems in People With StomasNaila Yulia WNo ratings yet

- Evaluating Skin Care Problems in People With StomasDocument8 pagesEvaluating Skin Care Problems in People With StomasNaila Yulia WNo ratings yet

- Evaluating Skin Care Problems in People With StomasDocument8 pagesEvaluating Skin Care Problems in People With StomasNaila Yulia WNo ratings yet

- 82167607Document6 pages82167607Naila Yulia WNo ratings yet

- 16258232Document14 pages16258232Naila Yulia WNo ratings yet

- Determination of The Effectiveness of Electronic Health Records To Document Pressure UlcersDocument10 pagesDetermination of The Effectiveness of Electronic Health Records To Document Pressure UlcersNaila Yulia WNo ratings yet

- 16258232Document14 pages16258232Naila Yulia WNo ratings yet

- Determination of The Effectiveness of Electronic Health Records To Document Pressure UlcersDocument10 pagesDetermination of The Effectiveness of Electronic Health Records To Document Pressure UlcersNaila Yulia WNo ratings yet

- Determination of The Effectiveness of Electronic Health Records To Document Pressure UlcersDocument10 pagesDetermination of The Effectiveness of Electronic Health Records To Document Pressure UlcersNaila Yulia WNo ratings yet

- 71515348Document11 pages71515348Naila Yulia WNo ratings yet

- Standardized Antibacterial Honey (Medihoney) With Standard Therapy in Wound Care: Randomized Clinical TrialDocument12 pagesStandardized Antibacterial Honey (Medihoney) With Standard Therapy in Wound Care: Randomized Clinical TrialNaila Yulia WNo ratings yet

- ErostorysDocument19 pagesErostorysMayLiuNo ratings yet

- Solved Rail Chapter 1Document7 pagesSolved Rail Chapter 1spectrum_48No ratings yet

- Types of Shops Shopping: 1. Chemist's 2. Grocer's 3. Butcher's 4. Baker'sDocument1 pageTypes of Shops Shopping: 1. Chemist's 2. Grocer's 3. Butcher's 4. Baker'sMonik IonelaNo ratings yet

- AIR Modeller 78 2018Document68 pagesAIR Modeller 78 2018StefanoNo ratings yet

- Wetted Wall Gas AbsorptionDocument9 pagesWetted Wall Gas AbsorptionSiraj AL sharifNo ratings yet

- Les Essences D'amelie BrochureDocument8 pagesLes Essences D'amelie BrochuresayonarasNo ratings yet

- of Biology On Introductory BioinformaticsDocument13 pagesof Biology On Introductory BioinformaticsUttkarsh SharmaNo ratings yet

- Manual GISDocument36 pagesManual GISDanil Pangestu ChandraNo ratings yet

- Job Vacancy Kabil - Batam April 2017 RECARE PDFDocument2 pagesJob Vacancy Kabil - Batam April 2017 RECARE PDFIlham AdeNo ratings yet

- UAW-FCA Hourly Contract SummaryDocument20 pagesUAW-FCA Hourly Contract SummaryClickon DetroitNo ratings yet

- NANOGUARD - Products and ApplicationsDocument2 pagesNANOGUARD - Products and ApplicationsSunrise VenturesNo ratings yet

- Case Study MMDocument3 pagesCase Study MMayam0% (1)

- Unit 8 Ethics and Fair Treatment in Human Resources ManagementDocument56 pagesUnit 8 Ethics and Fair Treatment in Human Resources Managementginish12No ratings yet

- Nuclear Over Hauser Enhancement (NOE)Document18 pagesNuclear Over Hauser Enhancement (NOE)Fatima AhmedNo ratings yet

- DiffusionDocument25 pagesDiffusionbonginkosi mathunjwa0% (1)

- LFAMS Fee Structure OCT'2013Document7 pagesLFAMS Fee Structure OCT'2013Prince SharmaNo ratings yet

- Peoria County Booking Sheet 03/01/15Document8 pagesPeoria County Booking Sheet 03/01/15Journal Star police documentsNo ratings yet

- NG Uk RTR 0220 r15 PDFDocument9 pagesNG Uk RTR 0220 r15 PDFDuong Thai BinhNo ratings yet

- Fishing Broken Wire: WCP Slickline Europe Learning Centre SchlumbergerDocument23 pagesFishing Broken Wire: WCP Slickline Europe Learning Centre SchlumbergerAli AliNo ratings yet

- Electro Acupuncture TherapyDocument16 pagesElectro Acupuncture TherapyZA IDNo ratings yet

- 2457-Article Text-14907-2-10-20120724Document6 pages2457-Article Text-14907-2-10-20120724desi meleniaNo ratings yet

- National Step Tablet Vs Step Wedge Comparision FilmDocument4 pagesNational Step Tablet Vs Step Wedge Comparision FilmManivannanMudhaliarNo ratings yet

- Laboratory Diagnosis of Parasitic DiseasesDocument57 pagesLaboratory Diagnosis of Parasitic DiseasesAmanuel MaruNo ratings yet

- (Template) The World in 2050 Will and Wont Reading Comprehension Exercises Writing Creative W 88793Document2 pages(Template) The World in 2050 Will and Wont Reading Comprehension Exercises Writing Creative W 88793ZulfiyaNo ratings yet

- Lord You Know All Things, You Can Do All Things and You Love Me Very MuchDocument4 pagesLord You Know All Things, You Can Do All Things and You Love Me Very Muchal bentulanNo ratings yet

- Jurnal RustamDocument15 pagesJurnal RustamRustamNo ratings yet

- Rubric On Baking CakesDocument3 pagesRubric On Baking CakesshraddhaNo ratings yet

- Ship Captain's Medical Guide - 22nd EdDocument224 pagesShip Captain's Medical Guide - 22nd EdcelmailenesNo ratings yet

- Bubba - S Food MS-CDocument2 pagesBubba - S Food MS-CDũng Trần QuốcNo ratings yet