Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Jurnal Ebscohost Needs Training

Uploaded by

johar7766Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Jurnal Ebscohost Needs Training

Uploaded by

johar7766Copyright:

Available Formats

28 ProfessionalSafety DECEMBER 2011 www.asse.

org

I N BRI EF

The rst step in developing a training

program is to determine whether train-

ing is needed.

A training needs assessment provides

some certainty that the time, money

and resources used to develop and

conduct training will deliver desired

performance-based results.

How is a training needs assessment

conducted? What model can be fol-

lowed? Does this model work across

different disciplines or industries?

Answers to these questions can guide

the development of an effective train-

ing needs assessment.

Tracey L. Cekada, D.Sc., CSP, CHSP, is an assistant professor of safety sciences

at Indiana University of Pennsylvania. She holds a B.S. in Occupational Health

and Safety from Slippery Rock University, an M.S. in Environmental Science and

Policy from The Johns Hopkins University, and a D.Sc. in Information Systems

and Communications from Robert Morris University. Cekada is a professional

member of ASSEs Western Pennsylvania Chapter.

Conducting an Effective

Needs Assessment

By Tracey L. Cekada

Program Development

Peer-Reviewed

A

n employee trips over

an open fi l e cabi net

drawer. Another has a

near hit while standing beneath

an overhead hoist. The typi-

cal solution: Training, training

and more training. But is this

really necessary? While work-

ers without occupational safety

and health training likely are at

greater risk for workplace injury

and illness, the critical ques-

tion is whether the training is

adequate (Cohen & Colligan,

1998). Sometimes, too much

training can dampen its effec-

tiveness and decrease its cred-

ibility. The difference between

effective and ineffective training may be death, in-

jury, pain, suffering and lost prots (Whiles, 1999).

A large amount of time and money is spent on

training. In 1992, Broad and Newstrom reported

that an estimated $50 billion was spent each year

on formal training, with another $90 to $120 billion

spent on less-structured, informal training. ASTD

(2010) estimates that in 2009, U.S. organizations

spent $125.88 billion on employee learning and

development. The group reports that nearly two-

thirds of the total ($78.61 billion) was spent on

the internal learning function, and the remainder

($47.27 billion) was allocated to external services.

How much training content do employees re-

tain 1 month, 6 months or 1 year after training has

been conducted? Estimates suggest that only 10%

to 15% of the content is retained after 1 year (Broad

& Newstrom, 1992). This problem is compounded

when an organization believes that its regulatory-

mandated requirements are met once training has

been completed and documented. They focus little

on whether the training was effective.

In some settings, training is seen as the answer

to all workplace-safety-related problems. In these

cases, training is implemented at every turn. Often,

www.asse.org DECEMBER 2011 ProfessionalSafety 29

this may leave real problems unresolved. Over-

training also can frustrate employees and cause

them to question the credibility of management

and the training program (Blair & Seo, 2007). Fur-

thermore, the transformation from implementing

required training to newer, performance-based

models only heightens the need to ensure that

training is the correct solution and, if so, that it is

effective (Holten, Bates & Naquin, 2000).

What Is a Training Needs Assessment?

Is training the right solution to workplace prob-

lems? To answer this, one can conduct a training

needs assessment. This assessment is an ongoing

process of gathering data to determine what training

needs exist so that training can be developed to help

the organization accomplish its objectives (Brown,

2002, p. 569). More simply put, it is the process of

collecting information about an expressed or im-

plied organizational need that could be met by con-

ducting training (Barbazette, 2006, p. 5).

Essentially, a training needs assessment is a pro-

cess through which a trainer collects and analyzes

information, then creates a training plan. This pro-

cess determines the need for the training; identies

training needs; and examines the type and scope

of resources needed to support training (Sorenson,

2002). Rossett (1987) explains that one conducts

a training needs assessment to seek information

about: 1) optimal performance or knowledge; 2) ac-

tual or current performance or knowledge; 3) feel-

ings of trainees and other stakeholders; 4) causes of

identied problems; and 5) solutions (p. 15).

Why Conduct a Training Needs Assessment?

A training needs assessment often reveals the

need for well-targeted training (McArdle, 1998).

Conducting an effective assessment ensures that

training is the appropriate solution to a perfor-

mance deciency.

For example, training is not the solution to prob-

lems caused by poor system design, inadequate re-

sources or understafng (Sorenson, 2002). In some

cases, increasing an employees knowledge and

skills may not resolve the problem or deciency. In

such cases, implementing training as the solution

may waste valuable resources and time.

A training needs assessment can help determine

current performance or knowledge levels related to

a specic activity, as well as indicate the optimal per-

formance or knowledge level needed. For instance,

a 25% increase in slips, trips and falls in the produc-

tion line area may indicate an emerging problem. A

needs assessment collects information about worker

competence or about the task itself in order to help

identify problem causes (Rossett, 1987).

For a training needs assessment to be effective,

its conductor must clearly understand the problem

and consider all solutions, not just training, be-

fore determining the best solution and presenting

ndings to management. When properly done, a

needs analysis is a wise investment for the organi-

zation. It saves time, money and effort by working

on the right problems (McArdle, 1998, p. 4).

Costly mistakes can arise when an organiza-

tion fails to conduct a training needs assessment

or conducts one ineffectively. For example, a com-

pany may rely on training to x a problem when

another solution would have been more effective

or may employ training without examining the

required performance skills needed for the task in

question.

Background: Training Needs Assessment

The scholarly literature available on training

needs assessments is limited. However, several

case studies report how specic organizations

or industries have conducted these assessments.

Moseley and Heaney (1994) examine reports of

needs assessments conducted across several disci-

plines and identify many models and techniques

in use. They report that different disciplines have

found different techniques that work.

Furthermore, research on this topic indicates that

an organizations individual characteristics, such as

size, goals and resources, public versus private sec-

tor, global marketplace and corporate climate, may

inuence the training assessment methodology.

Some characteristics may present unusual challeng-

es and require special tools for conducting a training

needs assessment (Hannum & Hansen, 1989).

Traditionally, a training needs assessment asks

employees to list or rank desired training courses.

Such an approach can include many employees.

However, while the results may temporarily boost

employee morale, the success in actually improv-

ing employee performance on the job is limited.

This may be because such an approach is not per-

formance-based and employees often identify their

training wants versus their training needs.

A training needs assessment

can help determine current

performance or knowledge

levels related to a specic

activity, as well as indicate the

optimal performance or knowl-

edge needed.

30 ProfessionalSafety DECEMBER 2011 www.asse.org

McGehee and Thayers (1961) three-tiered ap-

proach to conducting a needs assessment con-

tinues to serve as a fundamental framework. It

encompasses three levels of analysis: organization,

operations and individual. Today, operations anal-

ysis is more commonly called task analysis or work

analysis (Holton, et al., 2000).

Organizational Analysis

Organizational analysis examines where train-

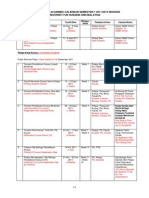

Figure 1

Example of a Training Needs Assessment

Questions to consider Uutcomes

Wby 1) Is there a performance deficiency in the

workplace?

2) How do we know this? What data is this

deficiency tied to? (e.g., absenteeism, productivity

loss, lost work days, injuries, grievances, damage to

equipment/personnel/environment)

3) Even if no performance deficiency exists, are

there expected changes in the workplace that may

impact performance (e.g., recent changes in

regulations; layoffs to staff that may require other

workers to pick up additional tasks; new processes

or equipment being installed)?

-Lmployees are provided with annual refresher training on

confined spaces. This training covers the minimum required by the

OSHA standard. No injuries or damage to equipment have occurred

in the past 5 years related to entry into any of these spaces.

-AlLhough initially everything may look all right, employees are

anticipating significant layoffs to the maintenance staff and

supervisory level employees. As a result, additional staff may need

to be pulled from other departments to assist employees during

entry into PRCS. These employees do not have the requisite

knowledge and handson experience to carry out the duties of the

attendant, entrant and entry supervisor.

Wbo 4) Who is involved in the performance deficiency?

5) If there are expected changes in the workplace,

who else could benefit from the training?

-MalnLenance department; supervisory personnel from the

maintenance, engineering and carpentry shops; employees from

the engineering and carpentry shops.

-Supervlsors from all divisions of facilities management could

benefit from this training so that they can properly educate staff.

How 6) How can performance deficiency be corrected?

7) Can training improve this performance

deficiency (e.g., was there a skill or knowledge

deficiency that led to the problem)?

-Whlle a current performance deficiency does not exist, it is

anticipated that once the layoffs take place, there is an increased

risk of employee injury if proper PRCS procedures are not followed

because current staffing needs will not be met. Because there may

be a change in assigned duties under these new conditions and

because some employees are new to the PRCS program, training

will be necessary. This training should be provided to the new staff

and reeducation on the current staff can improve performance.

Current staff who are familiar with PRCS entry procedures may

need to play a greater role in educating new employees to the

program.

Wbat 8) What is the best way to perform this specific job

task? This information can be gathered from

reviewing SOPs, regulations or job hazard analysis,

or by conducting interviews, conducting onsite

observations, reviewing best practices and

reviewing performance reviews.

9) Does the employee have these skills and this

knowledge? (This information can be gathered in

much the same way as #8 above.)

10) What are the critical tasks that have the

potential to produce personal, property or

environmental damage?

-SCs for entry into PRCS are available in the maintenance

department. The PRCS program also should be referenced. These

should both be used as the primary documents to reviewing PRCS

entry procedures.

-lL is expected that there will be two or three people on each shift

who can serve in one of the following capacities: 1) entrant; 2)

attendant; or 3) entry supervisor. However, employees should be

crosstrained to serve as either entrant or attendant. Supervisors

from all divisions of facilities management should be trained to

serve as entry supervisor. However, it is expected that supervisors

in the maintenance department should still have ultimate control

over the permits.

-8ecause of anticipated involvement between different divisions of

the facilities management department to carry out the PRCS

procedures, SOPs will need to be revised. Employees and

supervisors will need to be trained on new procedures. It is

recommended that all divisions of facilities management

(engineering, maintenance, carpentry, etc.) meet to discuss the

best approach to carrying out entry procedures.

-1ralnlng should cover at a minimum those requirements outlined

in 29 CFR 1910.146(h)(j).

Wben 11) When should training take place so that it

provides the most benefit to the employee and has

the least impact on business operations?

12) What format is most effective (e.g., classroom,

handson, selfdirected)?

13) What else is needed to make the training

successful?

-1ralnlng should take place as soon as possible after layoffs take

place. Training must occur before the scheduled quarterly entry

into the space. It is recommended that training take place for

approximately 1 hour at the start of the daylight shift. Evening and

nightshift employees should attend this training session as well.

-lL is suggested that during the training session employees will

actually go through the permitting procedures and be taken to one

of these PRCS for handson experience.

-8efresher training should be conducted annually. Additional

training may be necessary if there is a change in assigned duties, if

there is a change in permit space operations that presents a new

hazard, or when there are deviations or inadequacies in employee

knowledge.

www.asse.org DECEMBER 2011 ProfessionalSafety 31

ing is needed and under what conditions the train-

ing will be conducted. It identies the knowledge,

skills and abilities that employees will need for the

future as the organization and their jobs evolve or

change (Brown, 2002, p. 572).

Through organizational analysis, data are col-

lected by considering such items as absenteeism,

safety incidents, lost workdays, turnover rates,

grievances, customer complaints or other perfor-

mance problems. These data can then be evalu-

ated to indicate where training could improve

performance. The organizational analysis phase

also should plan for workplace changes, such as

skills needed in the future, workforce demograph-

ics, and evolving laws and regulations (Brown).

Future Skills

Understanding how an organization may be

changing helps to identify skill needs. For exam-

ple, will new equipment be installed or new pro-

cesses implemented? Will standards or regulations

change? Will technology change? Will employees

need communication and interpersonal skills to

better work with other employees or in teams? Will

cultural changes occur within the organization?

Labor Pool

An organizations labor pool may change as

more older people enter the workplace or as wom-

en or other minorities become more prominent. As

the economy changes and operating costs adjust,

the workplace may need to change. For example,

becoming a global organization will require chang-

es. Understanding the effects of such changes will

help an organization better accommodate employ-

ees needs while still meeting organizational needs.

Laws & Regulations

Changes in safety and environmental regulations

as well as adoption of other laws may dictate that

an organization provide training in specic areas.

For instance, employees who work with hazard-

ous materials may need annual refresher training.

Under the Family Medical Leave Act or Americans

with Disabilities Act certain information may need

to be shared with employees. Changes in policies

related to workplace violence or sexual harassment

also must be communicated.

Operations/Task Analysis

Operations/task analysis examines each jobs

knowledge and skills requirements and compares

these requirements to employees actual knowl-

edge and skills. Any gaps indicate a training need.

Sources for collecting operations/task analysis data

include job descriptions, standard operating proce-

dures, job safety analyses/job hazard analyses, per-

formance standards, review of literature and best

practices, and on-site observation and questioning

(Miller & Osinski, 1996).

According to Brown (2002):

[A]n effective task analysis identies:

tasks that have to be performed;

conditions under which those tasks are to

be performed;

how often and when tasks are performed;

quantity and quality of performance re-

quired;

skills and knowledge required to perform

tasks;

where and how these skills are best ac-

quired. (p. 573)

Individual Analysis

Individual analysis examines a worker and how

s/he is performing the assigned job. An employee

can be interviewed, questioned or tested to deter-

mine individual level of skill or knowledge. Data

also can be collected from performance reviews.

Performance problems can be identied by

looking at factors such as productivity, absentee-

ism, tardiness, accidents, grievances, customer

complaints, product quality and equipment repairs

needed (Miller & Osinski, 1996). When decien-

cies are identied, training can be established to

meet the individual employees needs.

The three levels of the needs analysis are inter-

related and data need to be collected at all levels for

the analysis to be effective. Based on the informa-

tion gathered, management can identify training

needs, establish learning objectives, and develop

a training program that meets organizational and

employee needs.

Training Needs Asssessment: Models & Key Steps

McClelland (1993) discusses an open-systems

model for conducting training needs assessments.

This model involves an 11-step approach to con-

ducting a training needs assessment:

The three levels of the needs

analysis are interrelated and

data need to be collected at all

levels for the analysis to be ef-

fective. Based on the informa-

tion, management can identify

training needs, establish learn-

ing objectives and develop a

training program.

32 ProfessionalSafety DECEMBER 2011 www.asse.org

1) Dene assessment goals.

2) Determine assessment group.

3) Determine availability of qualied resources to

conduct and oversee the project.

4) Gain senior management support and com-

mitment.

5) Review/select assessment methods/instru-

ments.

6) Determine critical time frames.

7) Schedule and implement.

8) Gather feedback.

9) Analyze feedback.

10) Draw conclusions.

11) Present ndings and recommendations.

Barbazette (2006) indicates that a training needs

assessment answers typical questions such as why,

who, how, what and when.

Why: Asking why helps to tie the performance

deciency to a business need and examines wheth-

er the benet of the training is greater than the cost

of the current deciency.

Whn: Asking who is involved in the perfor-

mance deciency will reveal the target audience

and help the trainer customize the program ac-

cordingly. It also is important to identify anyone

else who may benet from the training.

Hnw: Asking how the performance deciency

can be corrected helps determine whether training

is the correct solution. It examines whether a skill

or knowledge deciency led to the problem.

What: Asking what is the best way to perform

a specic job task will help achieve desired results.

Perhaps standard operating procedures outline how

to perform a task or maybe government regulations

must be considered when completing a task.

The trainer also must determine what occupa-

tions are involved in the deciency. This helps

identify critical tasks that have the potential to pro-

duce personal or property damage. This process

may involve reviewing accident data and records,

and interviewing various employees to

gain insight.

Whcn: Asking when training can best

take place helps minimize impact on the

business. Also, it is important to ask what

else is needed to ensure that the training

is delivered successfully.

The models available can guide the

process of developing an assessment

methodology. One conclusion based on

the literature research is that no single

model works in every situation. Instead,

the literature available can more purpose-

ly serve as a set of guidelines, principles

or tools (Holton, et al., 2000).

As noted, assessing training needs is

the rst step in developing a training pro-

gram (Rogers, 1991). To determine what

type of model or guidelines to follow

when selecting a training needs analysis

technique, Brown (2002) suggests asking

the following questions:

1) What is the nature of the problem

being addressed by instruction?

2) How have training needs been iden-

tied in the past and with what results?

3) What is the budget for the analysis?

4) How is training needs analysis perceived in

the organization?

5) Who is available to help conduct the training

needs analysis?

6) What are the time frames for completing the

exercise?

7) What will be the measure of a successful train-

ing needs analysis report?

The amount of time spent conducting a training

needs assessment varies based on organizational

needs, resources, amount of time available and

management commitment. However, the basic

steps in conducting a training needs assessment

include:

1) Determine the purpose for the needs assess-

ment and what questions need to be answered.

Typically, needs assessments are used to pro-

vide data for budgeting or scheduling purposes

(DiLauro, 1979). However, one should consider

other needs, such as identifying individual skill

or knowledge needs, organizational development

needs, nancial planning, stafng concerns and

performance improvement needs.

2) Gather data. A wealth of knowledge can be

collected by using tools such as observations, ques-

tionnaires, interviews, performance appraisals, fo-

cus groups, advisory groups, tests and document

reviews. The best approach may involve a combi-

nation of methods such as focus groups followed

by observation that may reinforce or support the

focus group ndings.

A signicant amount of information is available

regarding the proper design of questionnaires, as

well as how to properly word interview questions

so that they are not leading or too limited to gath-

er valuable information. This topic is beyond the

scope of this article.

Training Departments

Annual Review Questionnaire

1) List courses the training department is currently con-

ducting for your department, then indicate how satised

you are with the results of each course.

2) List any of your departments individual employees

who have specic training needs to improve current job

performance.

3) List any additional training that you or your employ-

ees require in order of need.

4) List any training requirements that you believe will

develop within the next year.

5) List any other areas in which the training department

can be of assistance to you and your employees.

Note. Questionnaire from How to Identify Your Organiza-

tions Training Needs (pp. 84-85), by J.H. McConnell, 2003,

New York: American Management Association.

www.asse.org DECEMBER 2011 ProfessionalSafety 33

3) Analyze data. This step involves identify-

ing any discrepancies or gaps between employees

current skills and knowledge and those required or

desired for the job.

4) Determine what needs can be met by training.

Identify performance problems that can be correct-

ed by increasing employees skills or knowledge

base. Problems related to issues such as motiva-

tion, morale, resources, system design or learning

disabilities should not be addressed by training.

5) Propose solutions. If the solution is related

to a training deciency, then a formal or informal

training program may be needed.

Training Needs Assessment: An Example

Figure 1 (p. 30) presents a simplied example of

a training needs assessment for a small organiza-

tion (fewer than 100 employees) using Barbazettes

(2006) ve-question approach that identies the

why, who, how, what and when.

With respect to Figure 1, consider this scenario.

Maintenance employees in a manufacturing plant

must enter outdoor manholes (conned spaces)

each quarter to check water levels in these spaces.

If water buildup is a concern, then the water must

be pumped out. These spaces are considered per-

mit-required conned spaces (PRCS) so staff must

follow the companys PRCS entry program.

To simplify this process, McConnell (2003) cre-

ated an annual review questionnaire that a training

department can use to query department managers

at the start of the assessment process. This ques-

tionnaire is presented in the sidebar on p. 32.

Conclusion

A training needs assessment is a valuable tool to

determine what training needs exist in an organi-

zation and the type and scope of resources needed

to support a training program. When evaluating

training, one must differentiate between programs

that teach skills and those that convey information

(Charney & Conway, 2005).

Delivering information such as a policy change

involves conveying information. Enabling some-

one to perform a job more safely or efciently, or

that enables an employee to produce a higher-

quality product that reaps higher customer satis-

faction is teaching a skill.

Key Elements of an Effective Training Program

While not the focus of this article, creating

an effective training program encompasses

several key steps.

Cnnduct a cnst/bcnct ana!ysis nr

dcvc!np a busincss casc to determine the

nancial benet of conducting training.

Estab!ish c!car nb|cctivcs. Objectives

describe what learners will do; state the

conditions under which they will do it; and

establish criteria by which successful perfor-

mance will be judged (Molenda, Pershing &

Reigeluth, 1996). Training objectives should

be aligned with an organizations business

goals and mission. ANSI/ASSE Z490.1,

Criteria for Accepted Practices in Safety,

Health and Environmental Training, provides

guidance on writing clear, achievable and

measurable objectives.

Crcatc cnntcnt and instructinna! dc-

sign. Determine the most effective training

method for a particular situation. Classroom

training may be the most effective for one

situation, but less so for another. Or, a com-

bination of classroom and on-the-job training

may be most effective. Other delivery meth-

ods include video, web-based or computer-

based training.

Dctcrminc whcthcr tn usc in-hnusc

traincrs nr an nutsidc cnnsu!tant. In-house

training may cost less, provide more exibility

and bring greater hands-on knowledge of

the task at hand. An outside consultant may

build more interest and bring added credibil-

ity related to the topic.

Crcatc matcria!s that a!ign with thc

nb|cctivcs. Learning activities should en-

able learners to apply principles learned in

the classroom. To do this, the trainer must

understand the audience. Adults learn differ-

ently than young students and understanding

the challenges and assets related to instruct-

ing adults will improve training effectiveness.

TransIcr knnw!cdgc Irnm c!assrnnm

tn wnrkp!acc. Effective training enables the

learner to apply the knowledge gained in the

workplace. Barriers such as a lack of rein-

forcement on the job, interference from the

environment or a nonsupportive organiza-

tional culture can inhibit transfer of train-

ing (Broad & Newstrom, 1992). Coaching,

behavior observation, and accountability for

managers, supervisors and employees are just

a few ways to improve training transfer.

Eva!uatc training prngram ccctivc-

ncss. This process, critical to success, can

range from having trainees complete course

rating forms and taking posttraining tests to

more complex methods such as using leading

and trailing indicators (e.g., accident data re-

cords) to measure performance improvement.

Imp!cmcnt rccnmmcndatinns Irnm thc

cva!uatinn. These improvements may range

from changing training materials, time allot-

ment on content and facility location to actual

improvement in instructor performance, con-

tent and evaluation tools. If the assessment

process merely evaluates program effective-

ness, yet no recommendations for improve-

ment are implemented, then continuous

improvement will not occur.

34 ProfessionalSafety DECEMBER 2011 www.asse.org

A training needs assessment is the rst step in

establishing an effective training program. It is

used as the foundation for determining learning

objectives, designing training programs and evalu-

ating the training.

Conducting a training needs assessment is an

opportunity for managers and trainers to get out

into the organization and talk to people. Informa-

tion is collected, ideas are generated and energy is

created within the organization. Such excitement

can energize any training that may follow (War-

shauer, 1988).

A well-orchestrated training needs assessment

can deliver many positive outcomes, according to

Warshauer (1988):

1) increasing the commitment of manage-

ment and potential participants to training

and development;

2) increasing the visibility of the training

function;

3) clarifying crucial organizational issues;

4) providing for the best use of limited re-

sources;

5) providing program and design ideas; and

6) formulating strategies for how to proceed

with training efforts. (p. 16)

Other benets can include developing employ-

ees who have the skills and knowledge to perform

their jobs; meeting organizational performance

objectives; and improving relationships and em-

ployee morale (McConnell, 2003).

Training is often viewed as a nuisance and as a

costly endeavor rather than as a tool to boost the

organizations bottom line. This perception is rein-

forced when trainers fail to illustrate the cost/ben-

et of the training that they conduct.

Trainers must address the major question, What

is the difference between the cost of no training

versus the cost of training? (Michalak & Yager,

1979, p. 20). By illustrating the cost savings, train-

ers can provide a much clearer indicator (and gain

needed support) to proceed with training.

While the amount of scholarly literature on

training needs assessments is limited, several case

studies show how specic organizations or indus-

tries have conducted these assessments. The lit-

erature available can serve as a set of guidelines,

principles or tools to help SH&E professionals de-

sign a methodology for conducting training needs

assessments that work for their organizations. PS

References

AN5I/A55E. (2001). American National Standard

Criteria for Accepted Practices in Safety, Health, and

Environmental Training (ANSI/ASSE Z490.1-2001). Des

Plaines, IL: Author.

Amcrican 5ncicty Inr Training & Dcvc!npmcnt

(ASTD). (2010). 2010 ASTD state of the industry report.

Alexandria, VA: Author.

Barbazcuc, J. (2006). Training needs assessment:

Methods, tolls and techniques. San Francisco: Pfeiffer.

B!air, E. & 5cn, D. (2007, Oct.). Safety training: Mak-

ing the connection to high performance. Professional

Safety, 52(10), 42-48.

Brnad, M.L. & Ncwstrnm, J.W. (1992). Transfer of

training. Reading, MA: Perseus Books.

Brnwn, J. (2002, Winter). Training needs assessment:

A must for developing an effective training program.

Public Personnel Management, 31(4), 569-578.

Charncy, C. & Cnnway, K. (2005). The trainers tool

kit. New York: American Management Association.

Cnhcn, A. & Cn!!igan, J. (1998). Assessing occu-

pational safety and health training: A literature review

(NIOSH Publication No. 98-145). Cincinnati, OH: U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services, CDC,

NIOSH.

Dicthcr, J. & Lnns, G. (2000). Advancing safety

and health training. Occupational Health and Safety, 69,

28-34.

DiLaurn, T. (1979, Nov./Dec.). Training needs as-

sessment: Current practices and new directions. Public

Personnel Management, 8(6), 350-359.

Gupta, K. (1999). A practical guide to needs assess-

ment. San Francisco: Pfeiffer.

Hannum, W. & Hanscn, C. (1989). Instructional

systems development in large organizations. Englewood

Cliffs, NJ: Educational Technologies Publications.

Hn!tnn, E., Batcs, R. & Naquin, 5. (2000, Summer).

Large-scale performance-driven training needs assess-

ment: A case study. Public Personnel Management, 29(2),

249-267.

Mach!cs, D. (2002, Feb.). Training transfer strategies

for the safety professional. Professional Safety, 47(2),

32-34.

McArd!c, G. (1998). Conducting a needs analysis.

Menlo Park, CA: Crisp Learning.

McC!c!!and, 5. (1993). Training needs assessment:

An open-systems application. Journal of European

Industrial Training, 17(1), 12-17.

McCnnnc!!, J. (2003). How to identify your organiza-

tions training needs. New York: American Management

Association.

McGchcc, W. & Thaycr, P. (1961). Training in busi-

ness and industry. New York: Wiley.

Micha!ak, D. & Yagcr, E. (1979). Making the training

process work. New York: Harper & Row.

Mi!!cr, J. & Osinski, D. (1996, Feb.). Training needs

assessment. Retrieved Oct. 31, 2011, from www.ispi

.nrg/pdI/suggcstcdRcading/Mi!!cr_Osinski.pdI.

Mn!cnda, M., Pcrshing, J. & Rcigc!uth, C. (1996).

Designing instructional systems. In R. Craig (Ed.), The

ASTD training and development handbook. New York:

McGraw-Hill.

Mnsc!cy, J. & Hcancy, M. (1994). Needs assessment

across disciplines. Performance Improvement Quarterly,

7, 60-79.

Rnbntham, G. (2001, May). Safety training that

works. Professional Safety, 46(5), 33-37.

Rngcrs, M. (1991). Health and safety training. Ac-

cident Prevention, 38, 20.

Rnsscu, A. (1987). Training needs assessment. Engle-

wood Cliffs, NJ: Educational Technology Publications.

5nrcnsnn, 5. (2002, June). Training for the long run.

Engineered Systems, 19(6), 32.

Warshaucr, 5. (1988). Inside training and develop-

ment: Creating effective programs. San Diego: Univer-

sity Associates.

Whi!cs, A. (1999, Sept.). Workplace training: The

learning curve. Occupational Health and Safety, 68(9), 10.

Copyright of Professional Safety is the property of American Society of Safety Engineers and its content may

not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written

permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

You might also like

- 75005Document84 pages75005Jelita Kasih Adinda100% (1)

- Training Needs Assessment ProcessDocument8 pagesTraining Needs Assessment Processsolkar007No ratings yet

- 2017 Malaysia Super League Fixtures (Updated 24.1.2017)Document2 pages2017 Malaysia Super League Fixtures (Updated 24.1.2017)Media Fmllp100% (6)

- 21st Century Vocational TeacherDocument44 pages21st Century Vocational Teacherjohar7766No ratings yet

- 8 Step Training ModelDocument2 pages8 Step Training ModelMartin Ulv GregersenNo ratings yet

- Training Needs AssessmentDocument5 pagesTraining Needs AssessmentroxanabirsanNo ratings yet

- Postgraduate Academic Calendar Semester 1 2011/2012 Session Universiti Tun Hussein Onn MalaysiaDocument3 pagesPostgraduate Academic Calendar Semester 1 2011/2012 Session Universiti Tun Hussein Onn Malaysiajohar7766No ratings yet

- BI K1 PerakDocument21 pagesBI K1 Perakjohar7766No ratings yet

- A Qualitative Study On Perceptions and Knowledge of Orang Asli MotherDocument14 pagesA Qualitative Study On Perceptions and Knowledge of Orang Asli Motherjohar7766No ratings yet

- Models and Frameworks for Needs AssessmentDocument10 pagesModels and Frameworks for Needs Assessmentjohar7766No ratings yet

- Training Needs Analysis ExampleDocument1 pageTraining Needs Analysis ExampleAhmad SofianNo ratings yet

- The Competency Model of Hospitality Service: Why It Doesn't DeliverDocument11 pagesThe Competency Model of Hospitality Service: Why It Doesn't Deliverjohar7766No ratings yet

- Jurnal Koko2Document18 pagesJurnal Koko2Zaidi MusaNo ratings yet

- Soft SkillDocument7 pagesSoft SkillHamizilawati IshakNo ratings yet

- A Qualitative Study On Perceptions and Knowledge of Orang Asli MotherDocument14 pagesA Qualitative Study On Perceptions and Knowledge of Orang Asli Motherjohar7766No ratings yet

- The Evaluation of Learning and Development in The WorkplaceDocument30 pagesThe Evaluation of Learning and Development in The Workplacejohar77660% (1)

- Workforce Learning (Strong)Document22 pagesWorkforce Learning (Strong)johar7766No ratings yet

- A - Woman's Up and DownDocument16 pagesA - Woman's Up and Downjohar7766No ratings yet

- Teaching Differently A Hybrid DeliveryDocument11 pagesTeaching Differently A Hybrid Deliveryjohar7766No ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Chapter 05 Training and DevelopmentDocument5 pagesChapter 05 Training and DevelopmentNguyễn GiangNo ratings yet

- Cwqap HvacDocument5 pagesCwqap HvacAmjhar SharifNo ratings yet

- 09.safety PlanDocument99 pages09.safety Planusman khalidNo ratings yet

- E-Learning in The Banking Sectorcase Study of The National Bank of GreeceDocument12 pagesE-Learning in The Banking Sectorcase Study of The National Bank of GreeceIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Maxbridge Training and Cocsultancy A5Document9 pagesMaxbridge Training and Cocsultancy A5Awol AminNo ratings yet

- Comparative Police Systems: Singapore and PhilippinesDocument6 pagesComparative Police Systems: Singapore and PhilippinesChristian Acupan100% (3)

- APPLE INc Behavorial AnalysisDocument16 pagesAPPLE INc Behavorial AnalysisKamal Nagvani100% (2)

- BSBHRM615 Learner GuideDocument50 pagesBSBHRM615 Learner GuideSabik NeupaneNo ratings yet

- CBC-Grains Production NC IIDocument71 pagesCBC-Grains Production NC IIJemar Sultan Fernandez100% (1)

- Embed: Chippewa County Strategic PlanDocument12 pagesEmbed: Chippewa County Strategic PlanTom ChervenyNo ratings yet

- Participant Feedback FormDocument2 pagesParticipant Feedback FormQuanMasterNo ratings yet

- BSBSUS201 Learner Workbook V1.1 ACOTDocument39 pagesBSBSUS201 Learner Workbook V1.1 ACOTGopi chand Deevala50% (2)

- Training For Training ManagerDocument53 pagesTraining For Training ManagerSubroto Ghosh100% (5)

- Ethiopia Salt Mining Training ManualDocument32 pagesEthiopia Salt Mining Training ManualHenok DireNo ratings yet

- Kyle E. Braddock: 124 Loughridge RD 724-462-3311 (Cell) Beaver Falls, PA 15010Document3 pagesKyle E. Braddock: 124 Loughridge RD 724-462-3311 (Cell) Beaver Falls, PA 15010api-278799297No ratings yet

- Netball Practitioner 1Document54 pagesNetball Practitioner 1Ongica SolomonNo ratings yet

- Management Skills Case StudyDocument19 pagesManagement Skills Case StudyMadusha TisseraNo ratings yet

- Huawei Authorized Network Academy Instructor Guide V1.0Document16 pagesHuawei Authorized Network Academy Instructor Guide V1.0Guillermo CarrascoNo ratings yet

- Human resource management functionsDocument15 pagesHuman resource management functionssomasekhar reddy1908No ratings yet

- Teachers - Identity - in - The - Modern - World - An - CHOOSING TEACHING - p128 PDFDocument234 pagesTeachers - Identity - in - The - Modern - World - An - CHOOSING TEACHING - p128 PDFPatricia María Guillén CuamatziNo ratings yet

- 4.1-5 Training PlanDocument15 pages4.1-5 Training PlanChiropractic Marketing NowNo ratings yet

- Summer Training Report On Oil India LimitedDocument62 pagesSummer Training Report On Oil India Limitedsumit pujari100% (2)

- Dharmaraj Project Front PageDocument76 pagesDharmaraj Project Front PageSweety RoyNo ratings yet

- Unit 3Document82 pagesUnit 3TusharNo ratings yet

- ETEEAP Application FormDocument8 pagesETEEAP Application FormRALF HERNANDEZNo ratings yet

- Impact of Training and Development On Employee's Performance A Study of General EmployeesDocument54 pagesImpact of Training and Development On Employee's Performance A Study of General EmployeesHASSAN RAZA89% (35)

- OD Practicioner Job DescriptionDocument3 pagesOD Practicioner Job DescriptionGerald AbergosNo ratings yet

- Rationale and Expectations of The TrainingDocument2 pagesRationale and Expectations of The TrainingAicha KANo ratings yet

- DAN 260 Syllabus 9-16-20Document3 pagesDAN 260 Syllabus 9-16-20elaaNo ratings yet

- Why orientation is essential for all new employeesDocument4 pagesWhy orientation is essential for all new employeesBusteD WorlD0% (1)