Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A Texas Rebel's Fight For Her Land by SUZANNA ANDREWS More Magazine Sept. 2103

Uploaded by

Suzanna Andrews0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

213 views8 pagesHOW A DOWN-ON-HER-LUCK SINGLE MOTHER IN A RAMSHACKLE TRAILER REINVENTED HERSELF AS THE BRIGHT, BOLD, UNAPOLOGETICALLY OUTRAGEOUS VOICE OF THE ANTIFRACKING MOVEMENT

Original Title

A Texas Rebel's Fight for Her Land By SUZANNA ANDREWS More Magazine Sept. 2103

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentHOW A DOWN-ON-HER-LUCK SINGLE MOTHER IN A RAMSHACKLE TRAILER REINVENTED HERSELF AS THE BRIGHT, BOLD, UNAPOLOGETICALLY OUTRAGEOUS VOICE OF THE ANTIFRACKING MOVEMENT

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

213 views8 pagesA Texas Rebel's Fight For Her Land by SUZANNA ANDREWS More Magazine Sept. 2103

Uploaded by

Suzanna AndrewsHOW A DOWN-ON-HER-LUCK SINGLE MOTHER IN A RAMSHACKLE TRAILER REINVENTED HERSELF AS THE BRIGHT, BOLD, UNAPOLOGETICALLY OUTRAGEOUS VOICE OF THE ANTIFRACKING MOVEMENT

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

You are on page 1of 8

BY SUZANNA ANDREWS

PHOTOGRAPHED BY DAN WINTERS

HOW A DOWN-ON-HER-LUCK SINGLE

MOTHER IN A RAMSHACKLE

TRAILER REINVENTED HERSELF AS

THE BRIGHT, BOLD, UNAPOLOGETICALLY

OUTRAGEOUS VOICE OF

THE ANTIFRACKING MOVEMENT

BLIPP THIS PAGE

to watch Sharon Wilson throw down the

gauntlet at a Stop the Frack Attack rally.

september 2013 | more.com 131

According to the oil and gas industry and the scientists, politi-

cians and environmentalists who support it, fracking is a safe

drilling process that represents energy independence, a boom in

jobs and tax revenues and a cleaner alternative to coal and oil.

On the opposite side is a dierent set of scientists, politicians

and environmentalists, who say the benets of fracking have

been exaggerated and who are concerned about the possible

environmental and health risks of this drilling process. The

battle, says New York real estate and environmental lawyer

Elisabeth Radow, has created an army of citizen activists

ordinary Americans from Texas and California to Colorado

and Arkansas to New York and Pennsylvania who feel that

their lives and communities are being threatened by fracking.

At 60, Sharon Wilson is a leader of that army. Based in north

Texasthe heart of oil and gas land and frackings ground

zeroshe was one of the rst to sound an alarm about the

possible dangers. Shes a pioneer, says Radow.

Tough, blunt and witty, Wilson is the force behind

Bluedaze.com, an award-winning antifracking site that has

become a top source of news and data for the movement. An

investigator, advocate, instigator and grassroots organizer,

Wilsonaka TXsharon, her nom de bloghas been praised

by one supporter for shining the light of truth where its

needed. She has also won admiration for some of her more

dramatic tactics. At an energy-industry convention, for ex-

ample, she recorded executives as they talked about using

military psyops, or psychological-operations expertise,

against members of the media, environmentalists and

community opponents of fracking. Then she published

the audiotapes on her blog: cnsuoirs cnUcui vIiu

iurIv rvncxINc vnNis uovN read her headline.

The fracking industry and its supporters are not

amused. Wilson has had her records subpoenaed

and has been deposed by one energy company. Shes

been called a Communist, a crackpot, a lunatic, a

WILSON IS SLOUCHED in a comfortably worn brown

leather armchair in the cozy, light-lled living room

of her home in Allen, Texas, a prosperous suburb of

Dallas. Dressed in a T-shirt and jeans, she is checking

the hundreds of e-mails, texts and voice mails that have

come in throughout the day from some of the many

people who seek her advicea roster that includes lawyers,

environmentalists and newspaper reporters from around

the country. On the mantel opposite her sits a photograph.

Simply framed, it shows a beautiful woman, her face buoyed

by clouds of uy blonde hair, staring at the camera through

eyes that look just this side of awake. She wears a peasant

blouse and a small, pillowy pout. There is a shadow of

physical resemblance to the Sharon Wilson of todaythe

high cheekbones, the watchful, catlike green eyes and the

blonde hair, although it is shorter now, and fadedbut in

attitude and demeanor the woman in the armchair seems very

dierent. That, she says of the photograph, was another life.

During that life, which ended not so long ago, Wilson was

living in a remote, dilapidated trailer with spotty electricity

and a cracked tub that leaked all over the bathroom oor. A

single mother facing a mountain of bills, she felt helpless and,

she says, almost out of hope. Then, in 2008, an energy company

paid her a $20,000 signing bonus and promised $1,200 a month

in royalties for the right to frack natural gas under her property.

I actually begged them to drill my land, she says, widening her

eyes as if still in disbelief at the distance she has traveled. Now,

ve years after making that deal, Wilson is one of the countrys

most outspoken critics of the oil and gas industry, and she has

galvanized opposition to what many consider either the most

promising or the most dangerous method of energy extraction today.

One of the most contentious issues in the nation, hydraulic

fracturingthe process of injecting uids deep into the ground at

high pressure in order to break up the shale to release the natural gas

withinhas divided families and pitted neighbor against neighbor.

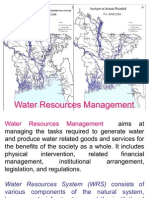

Source: U.S. Energy Information

Administration, based on data from

various published studies.

Current shale plays

Prospective shale plays

Basins

ARE YOU ON THE FRACK TRACK?

THE RUSH IS ON to mine the estimated 750 trillion cubic feet

of natural gas locked in basins (depressions) throughout the

country. Thanks to hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, drilling

has proliferated over the past decade. Here are the currentand

futureshale gas and oil plays in the continental United States.

To learn more about activity in your area, go to eia.gov/state.

H

A

I

R

A

N

D

M

A

K

E

U

P

:

V

E

R

O

N

I

C

A

M

A

R

T

I

N

E

Z

.

M

A

P

D

R

A

W

N

B

Y

O

U

R

D

E

S

I

G

N

S

liar and a hypocrite, because I leased my mineral rights and I still

get royalty checks from the gas company, she says with a smile that

is deant but also a little hesitant around the edges. There is a part

of Wilson that is uncomfortable with the life she now leads. The

sleek, manicured lawns and stately redbrick homes of her upscale

neighborhoodwhere her weather-beaten garden fence, front-yard

rain barrel and solar panels raise eyebrowscontrast sharply with

the life she once led. At times she feels as though she doesnt t

in anywhere, almost like a stateless person. As Wilson is the

rst to admit, she is not always as tough as she looks, acting,

she says, from fear as often as I do from courage. Still, most

of what propels her now is angerat what people have suered,

at the trampling of their land and health and the environment

by powerful corporations that she believes have tried to sup-

press the truth about fracking in order to reap big prots. I

became angry and loud, she says. I wasnt always that way.

reaming of easy money

BORN AND RAISED in Fort Worth, Wilson was the only

daughter of a single mother, a staunchly conservative and

religious woman who brought up her three children on

a secretarys salary, she says. Her father left the family

when she was two, and she never saw him again. We

were very, very poor, she says. I was teased for wearing

hand-me-downs and for not having a father. She spent

weekends and vacations at her maternal grandparents

ranch south of Fort Worth, where the only friends she

recalls were her horses, a dog, cats and the wildlife

she rescued. Her grandfather, a retired police detective,

taught her to ride, work a tractor, haul hay, rope

cattle and shoot.

Wilson married at 19. It was what her mother

expected of her, she says, and the union lasted less

than a year; she was married again by the time she

turned 26. She dreamed of going to college but

took only one class, a business course at Texas

Christian University, before dropping out be-

cause she was pregnant with her first child,

Frank, now 30. By 1985 her second marriage

had ended, and Wilson found work as a secre-

tary for Champlin Petroleum. Like many other

Texans, she says, she grew up wanting a career in

the lucrative oil and gas industry. After Champlin,

Wilson worked for a rm that helped energy com-

panies boost their production revenues. She started

as a secretary and rose through the ranks, taking on

more analytical work and heftier pay. But she quit in

late 1995, bored and burned out by the corporate routine.

Wilson had long dreamed of owning land, a place

where she could keep her beloved horses instead of

boarding them. In 1996, with money she had carefully

saved, she bought 42 acres in Wise County. The prop-

erty was situated north of Fort Worth, on the edge of the

magnicent Caddo-LBJ National Grasslandsso soothing

and beautiful in the summers, she says, that when theres

a wind, it looks like a golden ocean. Wilson was in a new

relationship by then; in 1995 shed given birth to her second

son, Adam. Her life seemed to have settled into something

close to perfection. There were turkeys and owls in the woods

that surrounded her trailer, and deer in her front pasture. I

couldnt see another porch light at night, nothing, she says.

But Adams father left in 2002, and Wilson was once again on

her own. She went on to hold a series of dead-end jobs that she

refers to as soul destroying but that gave her skillsin graphic

design, computers, teaching, oce administrationthat would

later make her eective as an activist.

It was in 2003 that Wilson says she rst saw neighbors coming

home with brand-new fully loaded Dodge diesels and the highest-

quality 7X beaver hats, suddenly taking expensive vacations and

remodeling their homes. They had leased their mineral rights to the

oil and gas operators who had recently discovered that marrying two

technologieshydraulic fracturing and horizontal drillingcould

release the huge amounts of gas packed in the rock layers deep under

the Barnett Shale. It was the birth of modern-day fracking.

When Wilson bought her property, the sellers price did not include

its mineral rights. So she scraped together every extra cent she had and

purchased 50 percent of those rights, just in case an energy company

someday wanted to drill. With the new explosion of fracking in the area,

she was determined to lease the rights and reap the rewards. I thought,

OK, how am I going to get the most money for this? she recalls. I wanted

to be Jed Clampett. I even wrote a couple of [energy] producers and said,

Come drill on my property. Thats how much I didnt know.

It is a morning in late March 2013, and the huge Texas sky, thick with

clouds, is the color of dirty dishwater. Wilson is at the wheel of her tiny

33-miles-per-gallon Honda Fitshe gave up her pickup with gun rack several

years agodriving along country roads near the land she once owned. We

pass miles of woodland and pastures, where cattle and sheep graze. Everything

seems so peaceful, even with the gas wells dotting the landscape around us.

And then we come to the dead zone: a brown wound, some 500 feet square,

in the grasslands Wilson loved. The scar was burned into the ground around

2008 when, Wilson says, a trucker dumped his load of frack waste there. Five

years later, Wilson still tears up when she sees it. About a mile away, we stop

at an old well pad, one of the first drill sites in her area. It is just off the road,

near a stream. The scene is bucolic except for the grinding and whirring of

the gas compressor, which is so loud that I cant hear Wilson unless she shouts,

even though I am sitting right next to her.

HOW FRACKING

AFFECTS YOU

CAN IT make you rich? Can it

make you sick? Does it cause

earthquakes? For answers to

these and other questions, go

to more.com/fracking. (After a

frack-site visit, Wilson, above, suf-

fered health problems, so a friend

gave her this gas mask.)

september 2013 | more.com 133

Over the next few years Wilsons property was

surrounded by drilling. There were trucks tearing

up the roads, she says. Lights lit up the sky at night

like Vegas, and there were days when my whole sky

turned black. Life became increasingly unbearable; at

times, she recalls, I would get in the closet and shut

the door so my son couldnt hear me cry. Wilson had

become such a staunch opponent of fracking by then

that she no longer wanted to lease her mineral rights.

But she says she had little choice. An energy company,

Braden Exploration, was buying up local mineral rights,

and the family who owned the other half of the rights on

her land had leased theirs.

As it was, when Wilson leased her rights in October 2008,

she hired a lawyer and, according to Bradens president,

G. Christopher Veeder, negotiated terms that were signi-

cantly more favorable to [her] than the terms negotiated with

most of the other owners in the area. These included a no

drill clause, which allowed the company to drill horizon-

tally under her land but prohibited it from putting rigs on her

42-acre property. She also negotiated a $20,000 signing bonus

and royalties of 20 percent, which began at $1,200 and today

amount to payments to Wilson of about $800 a month.

n the edge of a volcano

WILSON HAS BEEN ACCUSED of hypocrisy for taking money from an

industry she assails. But she doesnt see it that way. What? Im

taking money when I didnt have much choice, so Im supposed

to shut up and let the industry trample people? I think I have

more responsibility to speak out about their abuses, because I am

involved in a business relationship with them, she says. As long

as they are harming the environment and people, I will continue

to come after them, and I will use their money to do it.

It is a view of fracking that Braden and the rest of the industry, along

with other supporters of the process, dispute. Echoing most industry

leaders, Bradens Veeder says oil and gas drilling is highly regulated

at both the state and federal level, adding that his own company has

a long history of compliance with these regulations. Hydraulic frac-

turing, he says, has been used safely for decades and in over a million

wells. And with these words he approaches the heart of the battle over

fracking today: How do you measure safe?

As frackings proponents regularly point out, there have been no scien-

tically proven cases indisputably linking fracking to health problems or to

water or air contamination. Indeed, according to the RRCwhich says its sta

bases regulatory decisions on science and factsnowhere in the regulators

records is there a single documented water-contamination case associated

with the process of hydraulic fracturing in Texas. Although reports suggest

that other aspects of the extraction process, such as wastewater disposal and

leaks from faulty well casings, can lead to contamination, critics, including

Wilson says her awakening happened slowly. When she began explor-

ing how to get the best deal for her mineral rights, she came across a

website for Earthworks, an environmental group based in Washington,

D.C., that was one of the rst to track the early results of fracking. I

didnt read it at rst, she says. I didnt want to read bad news. Mean-

while, the drilling began near Wilsons land. I remember one day

driving home and there was gray slimy stu oozing down the road

and into the creek, she says. But she wasnt sure what had caused it.

By around 2005, after she had written several companies in the

hope of leasing her mineral rights, Wilson began to pay closer at-

tention. I started reading a little about the pitsthe ponds at drill

sites where fracking wastewater is temporarily storedand all

of a sudden I realized, Oh. My. God. Theyre here. Shed seen the

pits as she drove around near her home but hadnt realized what

they were. Nor had she been aware of the toxic chemicals they

could contain, including hydrochloric acid and benzene. Wilson

called the Railroad Commission of Texas (RRC), the regulator

in charge of ensuring that the states groundwater is protected

from oil and gas industry activities, demanding that it clean up

the pits. She says the RRC told her it didnt know where the pits

were. She was shocked. It was her rst brush with how loosely

regulated fracking was. Many states lacked the resources to

closely monitor the drilling boom. But pro-business Texas was

also perceived as reluctant to police an industry that was very

generous with its political contributionsa reason that in

2010 the RRC, which was described by state representative

Lon Burnham as probably the most corrupt agency in the

state of Texas, was faulted by a state oversight commission.

Everyone, Wilson says with one of her hallmark rhetorical

ourishes, knows the state of Texas is captured.

There was no single event that led Wilson to start ght-

ing; rather, she says, it was many moments upon mo-

ments. One of the most important, she recalls, happened

with the simple act of turning on her tap. First, nothing

came out. Then the water ran black and slimy, and after

that gray and very sandy, before clearing up about two

weeks later. Today she says she could never prove that

the fracking around her property had caused her water

problem, but she began to spend every spare moment

researching the procedure and contacting experts.

Wilson, who blogged occasionally, began post-

ing about well leaks, air contamination and health

problems suered by people who lived near frack-

ing sites. Her blog was becoming frack central,

a place where others could turn to have their

questions answered.

BLIPP THIS PAGE

to vote in our survey.

SHOULD FRACKING BE

BANNED IN THE U.S.?

VOTE

YES NO

Wilson, generally agree that incontrovertible

scientic evidence is dicult to come by. But

they do not agree that this means fracking is safe

only that there hasnt been enough time or eort

put into examining these issues. Baseline testing

of water and air before fracking has begun would

provide valuable data but is rarely done. And a lot

of vital information cannot be publicly disclosed,

because it is buried in the sealed court records of

cases in which people have sued energy companies

for damages and won settlements.

Meanwhile, for critics of frackingand certainly

for many of those, including Wilson, who have lived

with itthe anecdotal evidence is enough to cause

serious alarm. On the health front, we are seeing the

same array of symptoms across the country, but very

little is being done to explore the causes, says David

Brown. A toxicologist, Brown helped found the South-

west Pennsylvania Environmental Health Project, which

assists people with health problems in the Marcellus

Shale, a bitterly contentious front in the fracking wars

that stretches from New York, Pennsylvania and Ohio

into West Virginia and Maryland. Nosebleeds, headaches,

rashes, neurological and breathing problemsthese are

some of the symptoms that have surfaced in fracking zones

and that should be met with an immediate investigation by

the CDC, Brown says. Look at the West Nile virus. There

were so few cases, but people acted immediately.

After signing the Braden lease, Wilson stayed on her land for

two years. But with all the fracking going on around her property,

she says, I felt like I was living on the edge of a volcano. In 2010

she moved to an apartment in the nearby town of Denton, leaving

her cherished horses in the care of a neighbor. The following year,

she sold her ranchland and gave the horses to the propertys new

owner. Today she speaks of leaving her land as the end of her

American dream. If you are living your dream, you dont just

tell yourself to stop dreaming it, she says. You have to find a

new one. But I couldnt. In fact, that dream had been a night-

mare for some time, what with Wilsons financial problems, her

struggles as a single working mother living alone far out in the

countryside and the stresses of a job that felt deeply unfulfilling.

Perhaps for that reason, the leasing of her mineral rights, the sale

of her land and, indeed, her whole confrontation with fracking

seem to have marked the rebirth of Sharon Wilson.

With her first check from Braden Exploration, Wilson bought her-

self some equipmenta laptop, a camera, a video recorder, binoculars

and made a $1,000 donation to Earthworks. She began to volunteer

for the group at night and on weekends while working her day

job as an office administrator at the University of North Texas.

She focused her volunteer work on Earthworks Oil and Gas Ac-

countability Project (OGAP), which helps communities around

the country that are affected by drilling.

n activist nds her voice

WILSON BEGAN to get extensive experience interviewing people

whose lives had been affected by drilling. Shed first heard

their stories through her blog. They just started contact-

ing me, she recalls. They sent photos, which she posted,

but then they started asking, Can you help us? she says.

Sometimes it was overwhelming. There were moments

when she would drop to the floor sobbing at the stories

she heardof sick children and dying pets, of desperate

parents who didnt know what to do when a rig suddenly

rose up in their yard, or the whole family got rashes,

or the air smelled so strongly of diesel fuel that they

couldnt breathe properly.

Steve Lipsky and Shelly Perdue, two of the people Wil-

son has been working with, live in Parker County. One

is a wealthy businessman, the other a personal assistant

struggling to make ends meet. Wilson says Lipsky and

Perdue illustrate that it doesnt matter if youre rich or

poor when dealing with the energy companies.

A single mother, Perdue lives in a trailer tucked in the

woods just outside the town of Granbury. Sitting with

Wilson in her front yard in the shade of an oak tree hung

with birdhouses and wind chimes, Perdue talks about

what has happened to her since 2009, when Range Re-

sources began fracking less than half a mile from her

home. There were the trucksgiant rigs that backed

onto her property, creating knee-deep ruts in her

lawn. There were the headaches she experienced

and the bouts of fatigue. And the fact that Perdue

says she cant drink her tap water. Tests conducted

by Range in 2010 showed high levels of methane,

but according to its spokesperson, Matt Pitzarella,

this was due to existing geological issues and

problems with the construction of Perdues well,

not the companys drilling. Still, although Range

told her she could safely drink her water after

the company installed a gas vent on her well,

Perdue is fearful of doing so. Her water, she

notes, can be lit on

DO YOU OWN WHATS UNDER YOUR HOME?

WHEN YOU BUY PROPERTYwhether a primary or secondary home, whether

in a suburban, rural or vacation areadont assume you are also buying

whatever lies beneath the ground, warns New York real estate and en-

vironmental lawyer Elisabeth Radow. Another party may own the min-

eral rights, meaning theres a chance that gas or oil could be extracted

from your land without your consent, affecting your property value for

years while someone else collects the royalties. To nd out what steps

you should take before you buyor how to check on the status of your

current propertygo to more.com/mineralrights.

september 2013 | more.com 135

continued on page 156

EPA then withdrew its order against

Range without explanation or any men-

tion of Lipskys water. According to re-

cent news reports, the EPA had come

under pressure from a top Washington

lobbyist working for Rangewhich the

companys spokesperson, Pitzarella, de-

nies, saying the lobbyist never worked

for or lobbied on behalf of Range, al-

though he did raise the Lipsky case with

the EPA. All of which left Lipsky to ght

the company on his own.

Lipsky has phoned Wilson repeat-

edly over the past few daysusually

when were about to sit down and

watch a movie, says her son Adam.

She takes every call. Peoples lives

fall apart; families are so stressed, she

says. Their whole paradigm crashes.

As Wilsons briey did when in 2012

she posted footage on her blog of Lip-

skys well water lighting on rea

video Pitzarella claims is deceptive

and Range came after her as well.

Alleging in a letter to her lawyer

that Wilson was making misrepre-

sentations about Range, the company,

as part of its case against Lipsky, sub-

poenaed Wilsons e-mails and deposed

her for six hours. She responded with

taunting blog posts. I declined their

invitation to be intimidated, she pro-

claimed. But she also got her rst pre-

scription for Ambien. Although in the

end Range never led suit against her,

for a while, Wilson says, I was afraid

that I was going to lose everything.

Perhaps because the rebel in her was

stied for so long, a big part of what mo-

tivates Wilson is the issue of power and

its abuse. In 2010 she gave a presenta-

tion to the EPA at its Research Triangle

Park facility in North Carolina, showing

them data, stats, blood tests, videos Id

gathered in doing Flowback, she says,

referring to an Earthworks report on

the Barnett Shale that she helped write.

I was presenting these case studies to

show there are signicant environmen-

tal and health impacts because the oil

and gas industry is saying that there

are no impacts. That any problems are

peripheral and they are taking care of

them. And these are the voices, she

says, that are the loudest.

There are industry lobbyists in there

every day, in Washington, in Austin,

re at her well; coming out of her taps,

it turns white and zzes.

Wilson is worried about Perdue.

I know what shes going through,

she says. That was my life. It took

Perdue divorced and working hard to

pay for her two acres of landfour years

to muster the courage to seek assistance.

You cant be a victim forever, she tells

Wilson, who has already assured her

that she can help: ling complaints with

the Environmental Protection Agency

(EPA) and the local Texas regulators,

arranging for more testing of her wa-

ter and soil, raising money to pay for a

water tank and a monthly water sup-

ply. Perdue is reluctant to take char-

ity. Ive done everything on my own,

she says. Her other concern is the back-

lash that could come from Range Re-

sources, which she knows responded

to her neighbor Steve Lipskys lawsuit

with a countersuit for $4.5 million, ac-

cusing him of defamation for alleging

publicly that Ranges drilling was the

cause of his water contamination.

Lipsky lives about a mile from Per-

due as the crow ies, in a 17-room pa-

laz zo outside Weatherford. Standing

in his sprawling kitchen overlooking

his swimming pool, he talks about the

nightmare that his life has become

since 2009, when, he says, he discov-

ered problems with his well water. To-

day he trucks in water for his family at

a cost of $1,000 a month because, he

says, his water has been contaminated

by methane and other chemicals. As

with Perduewho says her problems

began after the same well was drilled

in 2009Range insists that its drilling

is not to blame for Lipskys problems

but that the cause is an existing geologi-

cal issue, although this argument has

recently been challenged in an inves-

tigation by a local TV-news program.

For Wilson, Lipskys battle illustrates

how hard, and even surreal, it can be

to take on the oil and gas companies.

At rst, his allegation that Range was

responsible was backed up by an EPA

emergency order requiring the com-

pany to clean up the problem. But then

the Railroad Commission of Texas sup-

ported Range, saying it found no evi-

dence that the company was responsible

for Lipskys water contamination. The

Texas Rebel

continued from page 135

156 more.com | september 2013

158 more.com | september 2013

Texas Rebel Arctic

from page 128

tougher than the rest of us: the rst one

up every morning, the last one inside at

night. Her beauty ran deep, a product of

spirit, not cosmetics. And if she could

do this, dang it, I could, too.

NICOS ICE BATH was ready on our last af-

ternoon at camp. Michaela snapped

pictures as he streaked to the hole.

Somehow he persuaded the other men,

one by one, to follow his lead. They re-

turned to the cabin pink and swaggering,

urging us ladies to give it a try. Anyone

can roll in snow, Nico announced. This

is special. It was 22 degrees below zero

outside, but I am a sucker for a dare. So

I sat in the sauna until I thought my

eyeballs would blister. Then, before ra-

tionality could set in, I sprinted, naked

and steaming, to the holes icy ledge,

slipping and sliding my way in. The wa-

ter was surprisingly gentle on the skin,

less scratchy than snow. I dunked to my

armpits, grinning crazily, desperate to

get out, loving that I was in. Back in the

sauna, I felt as shining and phosphores-

cent as the aurora itself. For months my

bodys limits had dened me, but not

anymore. It wasnt that I felt invulnera-

blethose days are gone. But I was resil-

ient. And in the end, isnt that better?

PEGGY ORENSTEINs most recent book is

Cinderella Ate My Daughter: Dispatches from

the Front Lines of the New Girlie-Girl Culture.

she says as we drive back to her home

in Allen. We used to give people a

way to click on our website and send

an e-mail to legislators on key bills. And

now they are telling us that they dont

pay attention to e-mails. You have to

call or show up in person. How do peo-

ple do that? How do average citizens

aord $160 a day for hotel and food to

come to Austin? How do we match the

industry? If the president is going to

promote natural gas, he needs to listen

to people who live with natural gas. He

needs to do a y-in and listen.

Whether or not Obama, or any other

president, ever does this, Wilson will

be working her 18-hour days, lobbying,

amassing data and, above all, listening.

Shes now focusing on the Eagle Ford

Shale, in south and west Texas, where

wells are being drilled every day as if

in a modern gold rush. Photos on her

blog show a skyline dotted with smok-

ing ares. She wants to bring experts in

to talk to residents but worries about

how Earthworks will be able to pay for

that as well as the safe houses she

would like to establish for people who

dont have enough money to move even

though fracking, she says, is making

them ill. In their powerlessness, and

their voicelessness, Wilson sees a bit

of herself. And in helping them, she

may be helping herself.

Back at home, Adam jokes that he

is a big supporter of fracking, teasing

his ninja mom, as he has called her.

At 18, he is already in his third year of

college. Wilsons older son, Frank, lives

in Dallas. I tell my kids that they both

deserve a perfect mother and I am sorry

I wasnt one, she says, adding that shes

awed theyre not bitter. I learned a lot

from themthat you make your peace

about your past and you move on. And

then one day, after a long struggle, it

all comes together. Have you seen my

tattoo? Wilson asks. She got itand

the housein 2011, when Earthworks

made her its full-time organizer for

Texas OGAP. She pulls her hair away to

reveal the back of her neck and a tattoo

of an enormous dragonythe symbol

of transformation, she says.

SUZANNA ANDREWS is a contributing

editor at Vanity Fair.

READER SURVEY RULES

NO PURCHASE OR SURVEY PARTICIPA-

TION IS NECESSARY TO ENTER OR WIN.

Subject to Ocial Rules at www.surveygizmo

.com/s3/989068/Sweepstakes-Rules. The

$10,000 Reader Survey Sweepstakes begins

at 12:00 n\ ET on October1, 2012, and ends

at 11:59 v\ ET on September 30, 2013. Open to

legal residents of the 50 United States and the

District of Columbia, 21 years or older. Limit

one (1) entry per person and per e-mail address,

per survey. Void where prohibited. Sponsor:

Meredith Corporation.

BEAUTY BASKET GIVEAWAY

NO PURCHASE NECESSARY TO ENTER

OR WIN. Subject to Ocial Rules at more

.com/beauty-gift-basket. The Beauty Gift Bas-

ket Sweepstakes begins at 12 n\ ET on August

20, 2013, and ends at 12 n\ ET on Septem-

ber 20, 2013. Open to legal residents of the

50 United States and the District of Colum-

bia, 21 years or older. Limit one (1) entry per

person and per e-mail address. Data charges

may apply. Void where prohibited. Sponsor:

Meredith Corporation.

You might also like

- Lindsey Williams The Energy Non CrisisDocument102 pagesLindsey Williams The Energy Non Crisistorontochange100% (2)

- Jackpot: How the Super-Rich Really Live—and How Their Wealth Harms Us AllFrom EverandJackpot: How the Super-Rich Really Live—and How Their Wealth Harms Us AllRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Alexander Hamilton, RevolutionaryFrom EverandAlexander Hamilton, RevolutionaryRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (13)

- Amity and Prosperity: One Family and the Fracturing of AmericaFrom EverandAmity and Prosperity: One Family and the Fracturing of AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (52)

- In the Still of the Night: The Strange Death of Ronda Reynolds and Her Mother's Unceasing Quest for the TruthFrom EverandIn the Still of the Night: The Strange Death of Ronda Reynolds and Her Mother's Unceasing Quest for the TruthRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (91)

- A Colossal Wreck: A Road Trip Through Political Scandal, Corruption and American CultureFrom EverandA Colossal Wreck: A Road Trip Through Political Scandal, Corruption and American CultureRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (4)

- Ida M. Tarbell: The Woman Who Challenged Big Business—and Won!From EverandIda M. Tarbell: The Woman Who Challenged Big Business—and Won!Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (9)

- Gated Communities Social Sustainability 10Document157 pagesGated Communities Social Sustainability 10Gabriela Souza67% (3)

- Sagebrush Empire: How a Remote Utah County Became the Battlefront of American Public LandsFrom EverandSagebrush Empire: How a Remote Utah County Became the Battlefront of American Public LandsNo ratings yet

- Legacy of Luna: The Story of a Tree, a Woman, and the Struggle to Save the RedwoodsFrom EverandLegacy of Luna: The Story of a Tree, a Woman, and the Struggle to Save the RedwoodsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (90)

- Planet of SlumsDocument4 pagesPlanet of SlumsAmbar Mariel Paula DiazNo ratings yet

- Formula for Fortune: How Asa Candler Discovered Coca-Cola and Turned It into the Wealth His Children EnjoyedFrom EverandFormula for Fortune: How Asa Candler Discovered Coca-Cola and Turned It into the Wealth His Children EnjoyedNo ratings yet

- The Storm of the Century: Tragedy, Heroism, Survival, and the Epic True Story of America's Deadliest Natural DisasterFrom EverandThe Storm of the Century: Tragedy, Heroism, Survival, and the Epic True Story of America's Deadliest Natural DisasterNo ratings yet

- Silvio Napoli - CASE ANALYSISDocument4 pagesSilvio Napoli - CASE ANALYSISmoatik275% (4)

- The Energy Non-Crisis by Lindsey WilliamsDocument73 pagesThe Energy Non-Crisis by Lindsey WilliamsMiki MausNo ratings yet

- Whidbey Island floatplane crash victims rememberedDocument10 pagesWhidbey Island floatplane crash victims rememberedLori VegaNo ratings yet

- Government Support, Solar Energy Was Unlikely To Make Its Way Into American Lives.22 Hayes'sDocument48 pagesGovernment Support, Solar Energy Was Unlikely To Make Its Way Into American Lives.22 Hayes'sEvan JackNo ratings yet

- The Matter of the Departed Diamonds: The Ultimate Locked Room MysteryFrom EverandThe Matter of the Departed Diamonds: The Ultimate Locked Room MysteryNo ratings yet

- Diseases of Women Physician in 19th C. JacksonvilleDocument1 pageDiseases of Women Physician in 19th C. Jacksonvillemet6hylmonkeyNo ratings yet

- The Rise & Fall of The Eco-Radical UndergroundDocument6 pagesThe Rise & Fall of The Eco-Radical UndergroundVoltairine de CleyreNo ratings yet

- Discombobulation: When Clans Collide Under the Influence of Urban Renewal, Baby Boomers, Knuckleheads, and StupidvilleFrom EverandDiscombobulation: When Clans Collide Under the Influence of Urban Renewal, Baby Boomers, Knuckleheads, and StupidvilleNo ratings yet

- Weidemann Engine Perkins 104 22 Parts List DefresenDocument23 pagesWeidemann Engine Perkins 104 22 Parts List Defresencatherineduarte120300rqs100% (124)

- The Dallas Post 10-16-2011Document18 pagesThe Dallas Post 10-16-2011The Times LeaderNo ratings yet

- 12-14-11 EditionDocument32 pages12-14-11 EditionSan Mateo Daily JournalNo ratings yet

- Madam C. J. Walker: The Inspiring Life Story of the Hair Care EntrepreneurFrom EverandMadam C. J. Walker: The Inspiring Life Story of the Hair Care EntrepreneurNo ratings yet

- The Mysterious Murder of Pearl Bryan, or: the Headless HorrorFrom EverandThe Mysterious Murder of Pearl Bryan, or: the Headless HorrorNo ratings yet

- Radical Politics, Radical Love: Tom CookDocument9 pagesRadical Politics, Radical Love: Tom CookMiguel SoutoNo ratings yet

- Adventures with Indians and Game: Twenty Years in the Rocky MountainsFrom EverandAdventures with Indians and Game: Twenty Years in the Rocky MountainsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1)

- The HOPE Coalition: H O P EDocument6 pagesThe HOPE Coalition: H O P EKornarosParaskeviNo ratings yet

- Blackstone Valley 4,2Document20 pagesBlackstone Valley 4,2Mister Holden100% (1)

- "Disco Inferno" VANITY FAIR July 2000 BY SUZANNA ANDREWSDocument11 pages"Disco Inferno" VANITY FAIR July 2000 BY SUZANNA ANDREWSSuzanna AndrewsNo ratings yet

- "Sins of The Mother" VANITY FAIR March 2000 by Suzanna AndrewsDocument13 pages"Sins of The Mother" VANITY FAIR March 2000 by Suzanna AndrewsSuzanna Andrews100% (1)

- The Demanding, Caring, Ambitious, Infuriating, Fearless Eva Moskowitzitz MORE September 2014 by Suzanna AndrewsDocument7 pagesThe Demanding, Caring, Ambitious, Infuriating, Fearless Eva Moskowitzitz MORE September 2014 by Suzanna AndrewsSuzanna AndrewsNo ratings yet

- The Widow's War by SUZANNA ANDREWS MORE Magazine January 2016Document8 pagesThe Widow's War by SUZANNA ANDREWS MORE Magazine January 2016Suzanna AndrewsNo ratings yet

- Arthur Miller's Missing Act - by SUZANNA ANDREWS Vanity Fair Sept 2007Document7 pagesArthur Miller's Missing Act - by SUZANNA ANDREWS Vanity Fair Sept 2007Suzanna AndrewsNo ratings yet

- Have You Looked Into My Heart? by SUZANNA ANDREWS More MagazineDocument10 pagesHave You Looked Into My Heart? by SUZANNA ANDREWS More MagazineSuzanna AndrewsNo ratings yet

- COURTING CONTROVERSY - by SUZANNA ANDREWS MORE MAGAZINE APRIL 2015Document9 pagesCOURTING CONTROVERSY - by SUZANNA ANDREWS MORE MAGAZINE APRIL 2015Suzanna AndrewsNo ratings yet

- Oil and Gas Industry Article On FrackingDocument2 pagesOil and Gas Industry Article On FrackingChad WhiteheadNo ratings yet

- Presentation To IEEDocument17 pagesPresentation To IEEAbubakar MehmoodNo ratings yet

- Environmental ActionDocument13 pagesEnvironmental ActionAnggun Citra BerlianNo ratings yet

- Water AssignmentDocument3 pagesWater Assignmentapi-239344986100% (1)

- 20 Nov Final Draft Case Study - Rainfed AgricultureDocument94 pages20 Nov Final Draft Case Study - Rainfed AgricultureMPNo ratings yet

- Indian Rivers Inter-Link - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument13 pagesIndian Rivers Inter-Link - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopediajebin jamesNo ratings yet

- Scrapbook ProjectDocument8 pagesScrapbook ProjectAntonio, Jr. GalangNo ratings yet

- New (TRO) Temporary Restraining Order MotionDocument37 pagesNew (TRO) Temporary Restraining Order MotionNancyWorldNo ratings yet

- Stakeholder Analysis of Solid Waste Management Schemes in HyderabadDocument24 pagesStakeholder Analysis of Solid Waste Management Schemes in HyderabadJoniJaoNo ratings yet

- Traveller's Choice From North To South'Document3 pagesTraveller's Choice From North To South'Kevin kyle CadavisNo ratings yet

- Command Area SurveyDocument16 pagesCommand Area SurveyPKNAYAK123100% (1)

- EA SusWatch Ebulletin October 2018Document3 pagesEA SusWatch Ebulletin October 2018Kimbowa RichardNo ratings yet

- The Real Difference Between Boys and GirlsDocument19 pagesThe Real Difference Between Boys and Girlsdeepak202002tNo ratings yet

- Review of The SADC Inclusive Education StrategyDocument11 pagesReview of The SADC Inclusive Education StrategyGeorge Mwika KayangeNo ratings yet

- Developmental TaskDocument45 pagesDevelopmental Taskmaria luzNo ratings yet

- Chapter14 - Urban InfrastructureDocument30 pagesChapter14 - Urban InfrastructureIr Sufian BaharomNo ratings yet

- Water Efficient Fixtures ProjectDocument6 pagesWater Efficient Fixtures ProjectPochieNo ratings yet

- Environmental SanitationDocument18 pagesEnvironmental SanitationMelanie Ricafranca Ramos100% (1)

- Progress in Human Geography: Mapping Knowledge Controversies: Science, Democracy and The Redistribution of ExpertiseDocument13 pagesProgress in Human Geography: Mapping Knowledge Controversies: Science, Democracy and The Redistribution of ExpertiseBarnabe BarbosaNo ratings yet

- UNCOVER - For Your AttendanceDocument2 pagesUNCOVER - For Your AttendanceNaruto SasageyoNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Green ParadoxDocument20 pagesIntroduction To The Green ParadoxJames GNo ratings yet

- Cablegate COP15Document76 pagesCablegate COP15Benno HansenNo ratings yet

- 14 Water BangladeshDocument14 pages14 Water BangladeshA S M Hefzul KabirNo ratings yet

- Koenig Rainwater and CoolingDocument5 pagesKoenig Rainwater and Coolingrfmoraes16No ratings yet

- Three Mile Island ClosesDocument2 pagesThree Mile Island ClosesPennLiveNo ratings yet

- Project Proposal (School Supplies)Document2 pagesProject Proposal (School Supplies)paul dela cruzNo ratings yet

- Power and InterdependenceDocument2 pagesPower and Interdependencedillards81100% (1)