Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Westgate Attack - Nairobi Security Report September

Uploaded by

Mbute Wa MbiyuOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Westgate Attack - Nairobi Security Report September

Uploaded by

Mbute Wa MbiyuCopyright:

Available Formats

REPORT: KENYA

INDEX Nairobi North East Coast Rift Valley Map References INSO Info Page 2 6 9 10 11 12

Confidential - NGO use only No copy, forward or sale INSO 2013

Issue 21

16-30 Sept 2013

COUNTRY SUMMARY

The stand-out development countrywide during the past fortnight was the spectacular attack launched by Harakat al-Shabaab al-Mujahedin (HSM) militants against the Westgate shopping centre in Nairobi, the largest asymmetric operation the group has ever staged inside Kenya. The incident, a Mumbai-style assault and siege operation, was the realisation of an objective held by the Somali group since Kenyan military intervention in Somalia in 2011; from that time onwards, HSM has been attempting to demonstrate to the Kenyan government and people, as well as the large foreign national presence here, that this interventionseen by the group as violating the religious and political freedom of Somaliawould come with blowback. incident governmental learning. As such, we are highly unlikely to see further such attacks even in the medium term. Instead, it is much more probable that HSM, after a period of quiet, will try to launch more of the small-scale operations for which it is best known in this country, which are easier and less risky, but allow it to demonstrate a continued presence in Kenya in spite of security force actions to deny and disrupt them.

KEY POINTS HSM attack of unprecedented scale on Westgate shopping centre in Nairobi Elevated level of HSM activity in North Eastern in wake of Nairobi attack

Armed criminality targeting NGOs in Dadaab

INSO Kenya is Supported By

Evidence of this approach was already visible during the period, with a HSM attacks on police in the North Easts Mandera town shortly after the Westgate incident. Unusually for attacks on this nature in the province, HSM publicly claimed responsibility for the Mandera attack, clearly to capitalise on attention they had With more than 60 people, the majority garnered during the Nairobi siege. civilians, dead and almost 200 injured and more expected to be found during the Also in the North East, two NGO faciliongoing forensic investigationthis is the ties were attacked with small arms in sepamost serious instance of Islamist militancy rate incidents in Dadaab, although they in Kenya since the 1998 bombing of the were both attributed not to HSM but to US embassy, and is therefore a major coup armed criminals. Yet that in itself is probfor HSM. However, it is unlikely that it lematic, as part of a recent increase in the represents a decisive shift in the security willingness of non-HSM local actors to environment of Nairobi or the wider use violence to settle social and commercountry. Such high-impact acts of militan- cial grievances, particularly in relation to cy are rare for a variety of reasons, includ- the presence of non-local Kenyans. ing cost, likelihood of detection, and postThe International NGO Safety Organisation (INSO) is a registered charity in England & Wales no.1140276 and a company limited by guarantee no.7496737

The INSO Report - Kenya

Total Incidents NGO Incidents

Page 2

377 12

Nairobi Metropolitan Region

main entrances, firing coolly but randomly at civilians although subsequently allowing those who could demonstrate they were Muslims to go free. Before the first group of governmental security responders arrived, more than two hours later, many of the more than 60 fatalities (of which one was a Kenyan NGO staff member), and 175 non-fatal casualties, had already been inflicted. Many others also remained trapped inside, including staff and/or family from four NGOs, having managed to hide themselves inside shops, bathrooms or other locations in the building. And by this time, the attackers are believed to have already taken dozens of hostages.

Armed Siege of Westgate Shopping Centre

In the past fortnight, for the first time since 1998, Nairobi found itself the scene of a major instance of Islamist militancy, when more than a dozen al-Shabaab militants launched a Mumbai-style assault and siege against the upmarket Westgate shopping centre on September 21st. At approximately 1240hrs on Saturday, during the peak commercial period, 10-15 militants armed with assault rifles and grenades stormed into the shopping centre through its three

KDF-Led Breach Operation

Thus began a three day siege inside the complex, which, in spite of repeated attempts by a KDF-led force, could not be broken. The attackers were understood to have holed up in two separate locationsinside the large Nakumatt supermarket on the ground floor, and in a premises on the second floor from where they effectively repealed multiple penetration attempts over the coming days, using professional sniper and

The INSO Report - Kenya

Page 3

Nairobi Met. Region Cont.

small unit tactics to do so. The first minor success scored by the KDF-led force, which was backed up by foreign military advisors, were the release of three hostages on Monday. However, by this time it was also becoming clear to the security forces that the assailants were much better prepared, both tactically and logistically, than had been initially thought, meaning that this minor success was unlikely to translate into a decisive end to the standoff. Security force suspicions from that time that the attackers had in fact pre-placed equipment such as weaponry, ammunition and explosives were ultimately validated; a vehicle was later found in the basement car park that had been there for more than a month, and used as an armoury for the attackers during the siege. As such, by Monday afternoon, the KDF had determined to use stronger tactics to get inside and end the situation. To start with, the force lit a generator located to the rear on fire on Monday afternoon, to divert the assailants attention while attempting to breach at the front of the complex. This is not thought to have succeeded, and this led to much of the destruction inside the Nakumatt. On Tuesday, with the siege into its fourth day and no definitive gains made in penetrating the Nakumatt stronghold, the Kenyan military made a fateful decision. After considering and abandoning other options, the army is believed to have decided to rig and detonate an explosive device which collapsed the ceiling and upper floors of the Nakumatt on the attackers, none of whom are thought to have survived. While the government stated, on September 30th, that they believe there were no hostages remaining at the end of the siege after all, this is impossible to believe and inconsistent with what was understood during the siege, with Red Cross estimates at the time of writing suggesting that 39 people remain missing. This number may fall, but it is extremely unlikely that it will fall to zero. number and fate of the attackers, their national origins, and the precise group responsible. On the latter subject, while al Shabaab has claimed responsibility, what this means in practice remains unclear. It is likely that al Qaeda, with whom al Shabaab has rhetorically (and in some ways, operationally) aligned itself, were involved at the management level, perhaps assisting in training, target selection and operational protocols such as filtering out Muslims. Similarly, it is likely that the Muslim Youth Centre (MYC), also known as al-Hijra, played some role, either indirect or more immediate. On the one hand, it is believed that at least some of the attackers were non-Somali Kenyans, which, if true, would strongly point to MYC involvement in the recruitment stage at the very least, given their central role in recruitment for al Shabaab within Kenya. However, it is also probable that the MYC was more directly involved, for example in facilitating weaponry and operatives in Nairobi, and even perhaps at the operational management level. However, at its core this is understood to have been an al Shabaab operation, launched in a manner consistent with their established operational parameters inside Kenya. It is moreover faithful to their oft-asserted strategic intent with regard to the Kenyan government; since KDF military intervention in Somalia in 2011, al Shabaab has consistently stated that it is seeking to strike inside Kenyan territory for the purpose of demonstrating costs to this military mission. And this was precisely the message communicated via public channels by senior HSM figures as the Westgate incident was ongoing. In this way, the underlying message HSM intended to communicate with this attack is identical to that of its previous but smaller kinetic operations in Kenya. All that differed, therefore, in this operation was the scale of its ambitionan ambition that, through a high degree of tactical sophistication (even with simple weaponry), information security, and willingness to target civilians, was powerfully realised.

Parsing HSMs Responsibility

That being said, there remains significant opacity regarding even some of the basic details of the incident, including the

Absence of Forewarning

Most significantly, the attack seems to have come out of the

The INSO Report - Kenya

Page 4

Nairobi Met. Region Cont. 2

blue, with no real forewarning on the part of domestic or foreign security agencies. While reports are circulating at the time of writing that there was some prior knowledge of an impending attack, this was very generic information about HSM intent vis--vis Kenya, and would not have allowed for any specific operational response by the security forces. As such, as so often with large attacks such as this, there appears to have been no meaningful detection of the operation all the way up until it was launched on the morning of the 21st. the national capital; about half a dozen major HSM operations had been defeated, as well as some minor ones, missing just three significant kinetic incidents (two IEDs and a grenade attack) during 2012. However, it is not possible to stop every attack. And equipped with that knowledge, al Shabaab is likely to have specifically chosen to use simple weaponry, thereby lowering the chance of being detected, as well as to have chosen a soft target such as the Westgate, where superficial and ineffective security measures, such as simplistic sweeps of bags with metaldetecting wands, and cars with mirrors on wheels, would not offer any credible defence against a highly motivated and welltrained groups of militants.

Nairobis Security Environment

Even if the information had been somewhat less generic, the nature of Nairobis security environment makes it very difficult to take concrete security precautions in the absence of highly specific information of an impending attack. The city, a wealthy economic and political hub which is also home to highly deprived areas within city limits, is also just hours away from the Somali border. As such, since the KDF intervention in Somalia, Nairobi has existed in a kind of inverse Goldilocks Zone, where there are sufficient threats from HSM that the environment cannot be called truly permissive, but where there is sufficient normal life to make operational responses to general threat warnings of HSM intent extremely difficult to implement. Absent a total shutdown of much of the cityan inconceivable measurethe most plausible response to general threat warnings would have been to detail multiple armed teams at major facilities throughout the city, such as hotels, shopping centres and governmental complexes. However, it can be very difficult for governments to take such decisions, because of concerns over causing popular panic, and because of the financial and logistical implications of such a decision (especially for Kenyas badly under-resourced security sector). The is particularly the case if the threat warning is not timebound. As such, the best the government can do in this inverse Goldilocks Zone is to focus on pre-attack detection and disruption. Indeed, since 2011 the government has had an excellent record in detecting and disrupting HSM activity in

Security Force Response

After such a game-changing incident as this, the response by the security forces will be multi-faceted. For one, they have already begun search and arrest operations in eastern parts of the city where HSM and affiliated networks are long known to have a presence. On the 28th, APTU led an operation in Majengo to arrest MYC-affiliated youths, arresting 38, and further such operations in eastern Nairobi, Mombasa and Garissa can be expected. Furthermore, an enormous expansion of security force weaponry, gear and vehicles has begun, in what it still a nascent process but which is expected to be the single largest up-grade to Kenyas police and security force capabilities in the past two decades. A numerical expansion of the police was already in the pipeline after the March elections, but it is expected that this process will be quickened, all pointing towards a much more visible, operational capable security sector. This may include private security companies too, who are now pushing for a change to the current law that prevents them using firearms or wearing body armour.

The Humanitarian Community Response

Many NGOs are currently asking themselves the question of what this attack means for them, and their presence in Kenya.

The INSO Report - Kenya

Page 5

Nairobi Met. Region Cont. 3

Much of the answer depends on whether this was an outlier in the prevailing security environment, or instead marks the beginning of a new trend of such large-scale, civilian-focused militancy in urban Kenya. For INSO, the answer is the former. Large-scale operations like this are expensiveprobably somewhere between $50,000-$100,000and are therefore necessarily a rarely used weapon in the arsenal of groups such as al Shabaab, particularly in an area of secondary importance to them such as Kenya is. Furthermore, attacks such as this have a high chance of failure through detection, given the scale of activities needed to prepare and implement them. The history of such large plots in Nairobi demonstrates this; of the estimated half dozen since 2011, this is the first to have gotten through. It is, by contrast, much easier to launch a smallscale attack, such as a hit-and-run grenade or SAF attack, without being detected. As a result, low-impact operations tend to be high-frequency for militant groups like al Shabaab, just as high-impact operations tend to be low-frequency. Moreover, the powerful shock this will have delivered to the governmentin terms of re-evaluating its defence preparedness and the scale of the threat posed by HSMwill have been expected by HSM; groups in their strategic position usually know that in the wake of such an effective, high-casualty attack, it is much better to rest on your laurels for a time, rather than attempt another. Much more likely, therefore, than an attempt at a further large attack, is thatafter a period of quiet to protect against the governmental response to the Westgate incidental Shabaab will engage in a number of smaller, easier operations. These would allow them to demonstrate their sustained presence in Kenya, in gloating defiance of post-Westgate governmental efforts, without the attendant risks of losing money and men to a security sector eager to score a retaliatory win against them. Indeed, some of this has already been seen in the North East during the period, with an attacks on a police target in Mandera (see North Eastern for further details), which was publicly claimed by al Shabaab in a way not common for the group before the Westgate incident. As such, the threat environment for NGOs in Nairobi in the wake of this attack is highly likely to default to its pre-attack paradigm; that is, of widespread armed criminality and infrequent low-level HSM activity in the eastern districts of the city.

The INSO Report - Kenya

Total Incidents NGO Incidents

Page 6

390 35

North Eastern Province

Humanitarian Community Incidents

This reporting period witnessed one of the most serious attacks upon an NGO in Dadaab since INSO commenced operations, when, on September 26th, an unknown group of men attacked an NGO compound in Dadaabs IFO 1 camp using small arms and explosive devices. Lasting approximately ten minutes, the attack primarily targeted the mess hall where a number of staff were watching television, though residential tents and rooms were also hit. Fortunately, no NGO staff members were seri- For one, the targeting profile in these incidents is somewhat different from the typical pattern of HSMs kinetic activity. ously injured as a result of the incident. For example, the perpetrators did not target public locations On September 29th a second, somewhat similar attack occurred, frequented by non-local Kenyans, such as tea shops or restautargeting an NGO construction site in Dagahaley in the early rantsan established HSM targeting patternbut instead evening. A grenade was thrown into the site, where a non-local focused their efforts on economic targets. construction company sub-contracted by a local company to build a primary school for an NGO was working. In the inci- Also of note, to the best of our knowledge there was no comdent, five nonlocal Kenyan builders were injured, with no munication from HSM to the targeted NGO of an impending attack, a fact which is inconsistent with known parameters of NGO staff were onsite at the time of the incident. their behaviour vis--vis the NGO community (although there is not a strong history of this to draw on in the North East). HSM Authorship? In Somalia, HSM typically writes a letter to an NGO or makes Seen in the light of the HSM attacks on Nairobis Westgate a public statement, warning of its displeasure and demanding shopping centre, and on Wajir and Mandera police positions a change in behaviour or location, before they would choose during the fortnight (discussed below), these events are very the kinetic option. concerning. However, while HSM involvement in these incidents is possible, it is very unlikely. Instead, both incidents are much more likely to have been driven by community or criminal considerations. Moreover, a HSM assault can be expected to be more deadly. While the attack on the 26th demonstrated little regard for human life, neither was it a determined attempt to kill NGO staff. The assailants did not use great deal of ammunition,

The INSO Report - Kenya

Page 7

North Eastern Cont.

their explosive devices did not fragment, and they did not enter the compound to press the attack. The attack on the 29th did inflict significant casualties, but again, this disregard for the welfare of its targets does not exclude non-HSM actors from potential responsibility, and the tactical simplicity of the incident also points away from HSM.

Implications for NGOs

Yet, the potential emergence of a pattern of contractual or employment dispute resolution through violence is arguably a development of equal concern to HSM targeting, and would, given the frequency of such disputes in Dadaab, present a significant risk to NGOs operating in the camps, and particularly to their non-local staff. Formerly, while widely thought a permanent possibility, the use of violence during contractual or employment disputes was more sporadic in Dadaab; the Dadaab camps have a large NGO residential footprint, mostly non-local Kenyan staff who have lived alongside refugees since the 1990s, for the most part without incident. From the start of 2013 up to August this year, only a single instance of such use of violence was recorded. However, three occurrences have been observed since the start of August, each with key characteristics in common: non-local Kenyan presence in the camps and sensitivity over contractual/ employment issues. As such, there has been a notable increase in this type of activity in the past two months, even if during this period other disputes between NGOs and the local communitysome involving prolonged tension and sizeable disturbancesdid not erupt into actual violence. While incidents of violent direct action against NGOs are so far isolated to those humanitarian organisations operational in IFO 1 and may very well be unique to that camp, their specific programmatic cause remains unclear. This lack of clarity regarding a specific driver is concerning, and emphasises the need for other organisations, particularly those operating in IFO 1, to take prudent steps to minimise potential vulnerability. While it is too early in this nascent trend to say that this represents a definitive change in the security environment faced by NGOs, the community would be well advised to review its acceptance strategies, both generally and as they pertain to residential compounds, ensuring that, amongst other things, music and television is kept to acceptable volumes and times; that alcohol is not overtly consumed; and that staff maintain positive and appropriate relations with the refugee and host com-

Non-HSM Kinetic Activity in Dadaab

Instead, it is much more likely that both of these attacks were community or criminally driven, because of the presence of non-local Kenyans and their social and commercial activities. Socially, non-locals are mostly non-Muslims, and local displeasure has previously been publicly communicated over such issues as the playing of loud music and concerns about sexual relations with local women. The attack on the 26th is likely connected to this dynamic. However, it is notable that there was no communication of grievance from the local community immediately prior to the attack on the 26th (either through letters, meetings or demonstrations), indicating that it was probably the work of a small, independent and perhaps professionally criminal section of it. Commercially, the Dadaab camps have a history of criminally motivated kinetic attacks on both NGOs and non-local businesses, mostly in response to dissatisfaction with things like contract and employment choices, anti-corruption measures, and commercial competition. For example, an attack that took place in January of this year against an NGO then operating in IFO 1, injuring one staff member, is believed to have been programme-related. Similarly, grenade attacks on non-local Kenyan contractors, in Hagadera in 2012 and Dagahaley in 2011, were understood to be about commercial competition. The limited socio-political sway and significance of non-local private sector companies in Dadaab, when compared to the UN/NGO community for example, reduces the potential blowback on their assailants and therefore makes them much easier to strike. The incident on the 29thprimarily affecting a non-local company, although involving an NGOexhibited strong similarities to this pattern of criminally motivated attacks.

The INSO Report - Kenya

Page 8

North Eastern Cont. 2

munities, particularly with local women. In addition to acceptance, NGOs should also review security in residential compounds more generally. This would include ensuring the presence of first aid kits and trained responders; developing reaction plans to armed attacks on camps, covering a variety of scenarios and drilling staff on them; ensuring the wide dissemination of emergency numbers, particularly the nearest deployable police units; and developing the physical security of compounds, particularly in regard to maximising cover from view. indicates that, as a result, many members of the public are reluctant to cooperate with the police, fearing either extortion attempts or that that they themselves will come under suspicion. It is very likely that one of the primary aims of this attack was to reinforce the impact of Westgate. HSM attacks in Mandera spiked sharply in September, witnessing six in the course of the month, against an average of one per month in 2013, excepting the election period in March. It is unclear if this increased operational focus on the town is coincidental or has a direct connection to Westgate. The attack on the 26th was widely reported in the international media however, somewhat adding to the sense of insecurity in Kenya, thus achieving the aim outlined above. Located right on the Kenya-Somali border, Mandera is probably the easiest major town that HSM can strike in Kenya. The movement has active service units operating around nearby Bulo Xawa/Garbahaarey and it enjoys considerable support amongst sections of the Marehan clan in neighbouring Gedo Region. Thus HSM units can conduct hit and run attacks against security forces with relative ease, using tactics honed against SNA and ENDF forces and exploiting the border to prevent pursuit. Furthermore, the daily cross border flow of goods and people between Mandera and Bulo Xawa allow for easy infiltration to carry out more asymmetric attacks. It remains to be seen however, if HSM can maintain its operational focus on Mandera into the medium term. It is under some pressure in Gedo, which may distract it from less immediate targets, though the organisation may well maintain their focus, aiming to further reinforce a Kenyan sense of insecurity. While the campaign is ongoing, attacks on police stations in Mandera town, or in remote areas, will present the most risk to NGOs; as will police responses, such as nervous gunfire or punitive police operations. IEDs and targeted killings, while a risk, have so far caused little in the way of collateral damage.

HSM Activity in Mandera

On September 26th at 0240hrs, HSM operatives attacked the Central AP Camp in Mandera using small arms, RPGs and grenades. During a 30 minute gun battle, they killed one police officer and wounded two, incurring one casualty themselves. One of the wounded officers later succumbed to his wounds. The attack caused considerable destruction to the camp, seriously damaging two buildings and destroying a large number of cars. Not long afterwards, HSM claimed the attack on Twitter. Elements of the Rapid Deployment Unit (RDU) conducted a seemingly punitive operation on the afternoon of the 26th, assaulting a number of people in the Miraa market and forcibly closing businesses. Following on from suspicions that the perpetrators of the 26th escaped to Ethiopia, the Ethiopian security forces have reinforced their border crossing points and are conducting checks of guest houses and visitors in villages and towns close to the border. There was considerable apprehension in Mandera in the lead up to the attack, which came on the back of a series of HSM operations in Mandera in September, predominantly focused on the town, but also including an attack on a police post in remote Harer-Hosle. That campaign caused serious damage to public confidence in the security forces and local government officials. Furthermore, police actions in the wake of earlier attacks, which included arresting a number of taxi drivers only to release them for a fee, served only to reduce their standing further. Anecdotal reporting from the area

The INSO Report - Kenya

Total Incidents NGO Incidents

Page 9

132 1

Coast Province

Coastal Fallout from Westgate Incident

With the militant assault on the Westgate mall in Nairobi, it is likely that post-incident security focus will also turn to the Coast, where the Muslim Youth Centre (or al-Hijra), an affiliate of al Shabaab, has long maintained a presence. While there is no conclusive proof of these suspicions thus far, the Centre, or MYC, is believed to have been involved in the Westgate incident in some capacity; either indirectlythrough recruitment or more directly through facilitation and use of its urban Kenyan infrastructure, which is focused on Muslim-majority parts of Nairobi and Mombasa, by the attack team. Already in Nairobi, an ATPU-led operation in an MYC area on September 28th led to the arrest of 38 individuals, and it is likely that the security forces are looking to their existing profiles of the group to identify individuals of interest in Mombasa too. In this port city, the north-eastern district of Kisauni has a wellestablished MYC presence, with significant numbers of Kenyans from across the country known to have been radicalised in the districts mosques and to have subsequently crossed over to Somalia to fight on behalf of al Shabaab. Indeed, the only Islamist figure in Kenya to have spoken out in support of the Westgate incident has been the cleric popularly known as Makaburi, an MYC-affiliated man self-identified as sympathetic al Shabaab and al Qaeda, who is partly based in this part of the city.

regard to combatting this Islamist militancy in the Coast, which ultimately contributes to al Shabaabs numbers inside Somalia, is weakness in the judicial system. This is thought to be the reason why some leading Islamists have been killed rather than captured in recent years, and this fate is likely to be shared by Makaburi, once the immediate focus on the Westgate and its authors dies down. However, as in Nairobi such kinetic actions against the group is unlikely to lead to its deathperhaps instead galvanising the groups anti-state agenda.

Security Force Activity

Away from Westgate-related developments, September has seen the security forces continue their focus on drug-related activity impacting the Coast. There have been a number of arrests of criminals for drug-dealing in Kilifi, and seizure there, in Mombasa, and in Kwale, in the past six weeks. The security forces take a very intolerant approach to this sort of What such operations might mean in practice remains unclear, activity, making it worth avoiding if one is enjoying some as much of the problem that the security forces have had with coastal holiday time.

The INSO Report - Kenya

Total Incidents NGO Incidents

Page 10

277 10

Rift Valley Province

For the past one month, cattle rustling activities have been largely concentrated in the four counties of the North Rift: West Pokot, Samburu, Baringo and Turkana. These counties also continue to register the majority of inter-communal clashes in the region, mostly revolving around cattle theft, with other conflict-prone counties such as Elgeyo Marakwet and TransNzoia progressively registering a decreasing percentage of all the incidences recorded in the region in the past one year. During the past fortnight, the three main protagonists in the conflictthe Pokot, Samburu and Turkanaeach carried out the same number of raids, at three each. All the attacks were targeted against settlements occupied by rival communities, and focused on the regions rustling-prone areas, such as Pokot North, Samburu North, Turkana South and East Baringo where different communities border with each other. However, the latest attacks dont represent a significant escalation in pastoralist conflict in the North Rift. Rather, they serve to highlight the persistent nature of the conflict in the region, as well as highlighting the emerging trend in pastoralist conflict; that of minors herding livestock being abducted or killed during such raids. As an example, the attack against Pusol village in West Pokot by the Turkana on September 17th, and the two attacks perpetrated by the Samburu at Nalingangor village and against a settlement near Baragoi town on September 28th, all together resulted in the killing of three teenage girls. A teenage Samburu boy and girl were also shot and critically injured in Baragoi Division on the 18th and 27th respectively, in attacks perpetrated by Turkana raiders.

Going forward, the current pastoralist conflict in the North Rift has not led to significant alteration of the security environment in the region, with the latest attacks largely taking place in the traditional hotspots. However, the onset of delayed dry spells will likely alter regional security dynamics, likely leading to an increase in roadside banditry as affected communities seek alternative livelihoods to augment depleting livestock numbers.

The INSO Report - Kenya

Page 11

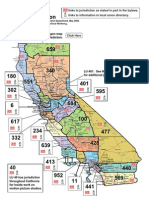

Map References

Legend

Data sources - Administrative boundaries: OCHA; Incidents reported: INSO. Mapping - With the kind assistance of ACTED Data, designations and boundaries contained on the maps included in this report are not guaranteed to be errorfree and do not imply acceptance by INSO.

INFO +

www.ngosafety.org

Circulation of this report for non-commercial purposes is permissible only with prior permission. Please contact director.ken@ngosafety.org

CONTACTS & INFORMATION

CENTRAL REGION OFFICE (NAIROBI) Central Regional Safety Analyst: Rory Brown, central.ken@ngosafety.org +254 (0) 712 288 409 Central Counterpart: Julius Kiprono, central2.ken@ngosafety.org +254 (0) 712 289 730 NORTH REGION OFFICE (DADAAB) NEP Regional Safety Analyst: Sean McDonald, north.ken@ngosafety.org +254 (0) 712 289 571 NEP Counterpart: Abdullahi Dimbil, north2.ken@ngosafety.org +254 (0) 712 288 392 COUNTRY MANAGEMENT (NAIROBI) INSO Kenya Director: Neil Barriskell, director.ken@ngosafety.org +254 (0) 729 205 005 Admin: Christine Kariuki, admin.ken@ngosafety.org +254 (0) 712 295 203

NOT INCLUDED THIS PERIOD:

Western, Eastern, Central and Nyanza Provinces These areas will be included in subsequent reports. If you have any information that would help us better understand the dynamics, please contact your local INSO Kenya office.

ADVISORY BOARD: INSO Kenya is overseen by an NGO Advisory Board. If you have any questions or feedback, good or bad, let them know on: advisory.ken@ngosafety.org REGISTRATION: NGOs can register up to five persons to each of INSO mailing lists. For a registration form please contactregistration.ken@ngosafety.org

COMMON ACRONYMS ACG - Armed Criminal Group AP - Administration Police GoK - Government of Kenya HSM - Harakat al-Shabaab al-Mujahideen IDF - Indirect Fire IO - International Organisation KPR - Kenyan Police Reserve MRC - Mombasa Republican Council NMI - Nyuki Movement for Independence RDU - Rapid Deployment Unit (Police) RTA - Road Traffic Accident TTP - Tactics, Techniques & Procedures AOG - Armed Opposition Group ATPU - Anti-Terrorism Police Unit GSU - General Service Unit (Police) IAF - Irregular Armed Forces IED - Improvised Explosive Device KDF - Kenyan Defence Forces KWS - Kenya Wildlife Service MY - Mombasa Youth NYS - National Youth Service RPG - Rocket Propelled Grenade SF - Security Forces UXO - Unexploded Ordnance

You might also like

- Kenya Al Shabaab Inteligence ReportDocument32 pagesKenya Al Shabaab Inteligence ReportWanjikũRevolution Kenya100% (2)

- Kenya�s 2013 General Election: Stakes, Practices and OutcomeFrom EverandKenya�s 2013 General Election: Stakes, Practices and OutcomeNo ratings yet

- Youth and Peaceful Elections in KenyaFrom EverandYouth and Peaceful Elections in KenyaKimani NjoguNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court: Full Judgement On Election Petition. - April 16, 2013Document113 pagesSupreme Court: Full Judgement On Election Petition. - April 16, 2013TheStarKenya100% (2)

- b113 Stalemate in Southern ThailandDocument18 pagesb113 Stalemate in Southern ThailandGohar HaaziqNo ratings yet

- Kenya Police Report On Drug Trafficking InvestigationsDocument48 pagesKenya Police Report On Drug Trafficking InvestigationsMutheu Mutua100% (2)

- Pillay Affidavit To Public Protector in Terms of Section 7 (4) (A) - 23 APDocument227 pagesPillay Affidavit To Public Protector in Terms of Section 7 (4) (A) - 23 APBranko Brkic100% (2)

- Kenya's Somali North East Devolution and SecurityDocument20 pagesKenya's Somali North East Devolution and SecurityInternational Crisis Group100% (1)

- Iran Cyber Final Full v2 PDFDocument86 pagesIran Cyber Final Full v2 PDFMeanGeneNo ratings yet

- Police Corruption and The Security Challenge in KenyaDocument26 pagesPolice Corruption and The Security Challenge in KenyaIzwazi McNortonNo ratings yet

- Report On Vetting of PS-ICT Enegy and PetroleumDocument23 pagesReport On Vetting of PS-ICT Enegy and PetroleumMwalimu MatiNo ratings yet

- 241 Thailand The Evolving Conflict in The SouthDocument37 pages241 Thailand The Evolving Conflict in The Southvlade_332No ratings yet

- Land ReportDocument32 pagesLand Reportjaffar s m100% (1)

- 4 - The Stella Sigcau DocumentsDocument18 pages4 - The Stella Sigcau DocumentsRight2Know CampaignNo ratings yet

- Internet Organised Crime Threat Assessment Iocta 2020 PDFDocument64 pagesInternet Organised Crime Threat Assessment Iocta 2020 PDFMihai RNo ratings yet

- Homeland Security Data Privacy and Security ChecklistDocument14 pagesHomeland Security Data Privacy and Security ChecklistJames Felton KeithNo ratings yet

- Communications Surveillance by The South African Inteeligence Services 2016 - ZA PDFDocument34 pagesCommunications Surveillance by The South African Inteeligence Services 2016 - ZA PDFTom SchumannNo ratings yet

- OSINT From A UK Perspective: Considerations From The Law Enforcement and Military DomainsDocument32 pagesOSINT From A UK Perspective: Considerations From The Law Enforcement and Military DomainsClaudia SerbanNo ratings yet

- World Bank Report On The Standard Gauge RailwayDocument5 pagesWorld Bank Report On The Standard Gauge RailwayMaskani Ya Taifa100% (2)

- Wildlife Trade PowerpointDocument8 pagesWildlife Trade Powerpointapi-3562436790% (1)

- Looting in Kenya-Kroll Report (Hapa Kenya Version)Document101 pagesLooting in Kenya-Kroll Report (Hapa Kenya Version)hapakenya100% (7)

- Colonial Report Annual Kenya Colony and Protectorate 1938Document67 pagesColonial Report Annual Kenya Colony and Protectorate 1938Lucas Daniel Smith100% (3)

- May 14 NewspaperDocument56 pagesMay 14 NewspaperAfricanagency KeyanNo ratings yet

- NigeriaDocument60 pagesNigeriaamanblr12100% (1)

- Persistent Aggrandizement? Israel's Cyber Defense ArchitectureDocument16 pagesPersistent Aggrandizement? Israel's Cyber Defense ArchitectureHoover InstitutionNo ratings yet

- Questions Regarding The Dar Rail ProjectDocument10 pagesQuestions Regarding The Dar Rail ProjectEvarist ChahaliNo ratings yet

- Maritime Security in Caribbean and Latin AmericaDocument8 pagesMaritime Security in Caribbean and Latin AmericaCandyce KelshallNo ratings yet

- FUTURE WAR PAPER TITLE- Unrestricted Warfare- A Chinese doctrine for future warfare? SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF OPERATIONAL STUDIES AUTHOR- Major John A. Van Messel, USMC .pdfDocument26 pagesFUTURE WAR PAPER TITLE- Unrestricted Warfare- A Chinese doctrine for future warfare? SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF OPERATIONAL STUDIES AUTHOR- Major John A. Van Messel, USMC .pdfDudley DeuxWriteNo ratings yet

- Executive Outcomes Against All OddsDocument10 pagesExecutive Outcomes Against All OddsSacha100% (1)

- Charter Bank Kenya ScandalDocument312 pagesCharter Bank Kenya Scandalopulithe100% (2)

- Mobile BankingDocument11 pagesMobile Bankingsuresh aNo ratings yet

- What I Learned in 40 Years of Doing Intelligence Analysis For US Foreign Policymakers Martin PetersenDocument8 pagesWhat I Learned in 40 Years of Doing Intelligence Analysis For US Foreign Policymakers Martin PetersenGeorge LernerNo ratings yet

- Kidnapping of School Pupils and Myth of Security in Northern Nigeria Causes and SolutionsDocument7 pagesKidnapping of School Pupils and Myth of Security in Northern Nigeria Causes and SolutionsEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- The Standard 20.05.2014Document80 pagesThe Standard 20.05.2014Zachary MonroeNo ratings yet

- Abu Sayaff GroupDocument8 pagesAbu Sayaff GroupLovely Jay BaluyotNo ratings yet

- OPERATION 'AURE': The Northern Military Counter-Rebellion of July 1966Document64 pagesOPERATION 'AURE': The Northern Military Counter-Rebellion of July 1966alagemo100% (4)

- How To Stage A Military Coup - Hebditch and ConnorDocument3 pagesHow To Stage A Military Coup - Hebditch and ConnormaumggNo ratings yet

- Comprehensive Assessment of The Insecurity & Terrorism Challenges in Nigeria and RecommendationsDocument30 pagesComprehensive Assessment of The Insecurity & Terrorism Challenges in Nigeria and RecommendationsDon OkerekeNo ratings yet

- Kenya - Report of The Committee On Westgate Attack - 4Document75 pagesKenya - Report of The Committee On Westgate Attack - 4Javier DuranNo ratings yet

- Achuzia's Account of Nigeria Civil WarDocument16 pagesAchuzia's Account of Nigeria Civil WarnaconnetNo ratings yet

- Defence AttachésDocument7 pagesDefence Attachéshiramamohammed100% (1)

- MI5 and MI6 Are Training Spies From UAE Ignoring UAE's Involvement in Libya War CrimesDocument5 pagesMI5 and MI6 Are Training Spies From UAE Ignoring UAE's Involvement in Libya War CrimesWar Crimes in MENANo ratings yet

- Dollars For Daesh Final ReportDocument48 pagesDollars For Daesh Final Reportjohn3963No ratings yet

- The American Empire and Its Media - Swiss Policy ResearchDocument7 pagesThe American Empire and Its Media - Swiss Policy ResearchDI EGOOOLNo ratings yet

- The Isaq Somali Diaspora and Pol2013Document26 pagesThe Isaq Somali Diaspora and Pol2013Khadar Hayaan Freelancer100% (2)

- The Role of Intelligence in National Security: Stan A AY ODocument20 pagesThe Role of Intelligence in National Security: Stan A AY OEL FITRAH FIRDAUS F.A100% (1)

- THE INDEPENDENT Issue 512Document44 pagesTHE INDEPENDENT Issue 512The Independent Magazine100% (1)

- UK House Foreign Affairs CmteDocument238 pagesUK House Foreign Affairs Cmtecorinne_marascoNo ratings yet

- History of HRM in The PhilippinesDocument11 pagesHistory of HRM in The PhilippinesAlexander CarinoNo ratings yet

- US NAVY Cyber Warfare EngineerDocument1 pageUS NAVY Cyber Warfare EngineerGuillaume BaNo ratings yet

- Huawei's Board of DirectorsDocument4 pagesHuawei's Board of DirectorsRob_OlsenNo ratings yet

- CRS Gun Control Legislation - Nov. 14, 2012Document118 pagesCRS Gun Control Legislation - Nov. 14, 2012dcodreaNo ratings yet

- Paul O'Sullivan Letter To Hogan Lovells, LondonDocument19 pagesPaul O'Sullivan Letter To Hogan Lovells, LondonHuffPost South Africa100% (1)

- N CurrentEventDocument6 pagesN CurrentEventBear NennoNo ratings yet

- US Kansas Intelligence Fusion Center Nairobi Westgate Mall Attack Lessons LearnedDocument15 pagesUS Kansas Intelligence Fusion Center Nairobi Westgate Mall Attack Lessons LearnedWilly OcksNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 ZackDocument13 pagesChapter 1 ZackZachariah AchinyanNo ratings yet

- DHS SmallUnitTacticsDocument6 pagesDHS SmallUnitTacticsDarren Burrows100% (1)

- U.S Department of State: Final Report November 17, 2015 ConfidentialDocument7 pagesU.S Department of State: Final Report November 17, 2015 ConfidentialJimNo ratings yet

- Country Report KenyaDocument18 pagesCountry Report KenyaMike ShakespeareNo ratings yet

- Silo Dryers: Mepu - Farmer S First Choice Mepu To Suit Every UserDocument2 pagesSilo Dryers: Mepu - Farmer S First Choice Mepu To Suit Every UserTahir Güçlü100% (1)

- Idlers: TRF Limited TRF LimitedDocument10 pagesIdlers: TRF Limited TRF LimitedAjit SarukNo ratings yet

- 6RA80 Quick Commissioning Without TachoDocument7 pages6RA80 Quick Commissioning Without TachoBaldev SinghNo ratings yet

- Mold Maintenance StepDocument0 pagesMold Maintenance StepMonica JoynerNo ratings yet

- SDS Super PenetrantDocument5 pagesSDS Super Penetrantaan alfianNo ratings yet

- Detailed Lesson Plan in Science IiiDocument3 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan in Science Iiicharito riveraNo ratings yet

- Acoustic Phonetics PDFDocument82 pagesAcoustic Phonetics PDFAnonymous mOSDA2100% (2)

- CA InsideDocument1 pageCA InsideariasnomercyNo ratings yet

- 2014 Catbalogan Landslide: September, 17, 2014Document6 pages2014 Catbalogan Landslide: September, 17, 2014Jennifer Gapuz GalletaNo ratings yet

- Brief List of Temples in Haridwar Is Given BelowDocument8 pagesBrief List of Temples in Haridwar Is Given BelowPritesh BamaniaNo ratings yet

- Igc 3 Practical NeboshDocument20 pagesIgc 3 Practical NeboshAbdelkader FattoucheNo ratings yet

- 2006 - Dong Et Al - Bulk and Dispersed Aqueous Phase Behavior of PhytantriolDocument7 pages2006 - Dong Et Al - Bulk and Dispersed Aqueous Phase Behavior of PhytantriolHe ZeeNo ratings yet

- Schrodinger Wave EquationsDocument6 pagesSchrodinger Wave EquationsksksvtNo ratings yet

- 020 Basketball CourtDocument4 pages020 Basketball CourtMohamad TaufiqNo ratings yet

- Final Project ReportDocument83 pagesFinal Project ReportMohit SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Traditional EmbroideryDocument38 pagesTraditional EmbroiderySabrina SuptiNo ratings yet

- Ansi/Isa - 75.08.04-2001 (R2013) Face-to-Face Dimensions For Buttweld-End Globe-Style Control Valves (Class 4500)Document16 pagesAnsi/Isa - 75.08.04-2001 (R2013) Face-to-Face Dimensions For Buttweld-End Globe-Style Control Valves (Class 4500)Horas CanmanNo ratings yet

- Pocket Book AGDocument67 pagesPocket Book AGsudiraharjaNo ratings yet

- Environmental and Sustainability Issues - 1Document21 pagesEnvironmental and Sustainability Issues - 121. PLT PAGALILAUAN, EDITHA MNo ratings yet

- DPWH ReviewerDocument597 pagesDPWH Reviewercharles sedigoNo ratings yet

- Hot Process Liquid SoapmakingDocument11 pagesHot Process Liquid SoapmakingPanacea PharmaNo ratings yet

- Samuelson and Nordhaus ch22 PDFDocument30 pagesSamuelson and Nordhaus ch22 PDFVictor ManatadNo ratings yet

- Dyson - Environmental AssesmentDocument16 pagesDyson - Environmental AssesmentShaneWilson100% (5)

- Substation Battery ChargerDocument2 pagesSubstation Battery Chargercadtil0% (1)

- MIKE21BW Step by Step GuideDocument124 pagesMIKE21BW Step by Step Guideflpbravo100% (2)

- The Sparkle EffectDocument22 pagesThe Sparkle EffectVida Betances-ReyesNo ratings yet

- Athens 803 and The EkphoraDocument18 pagesAthens 803 and The EkphoradovescryNo ratings yet

- Barium Chloride 2h2o LRG MsdsDocument3 pagesBarium Chloride 2h2o LRG MsdsAnas GiselNo ratings yet

- Grocery GatewayDocument2 pagesGrocery GatewayKumari Mohan0% (2)

- 300 20Document3 pages300 20Christian JohnsonNo ratings yet