Professional Documents

Culture Documents

New Zealand Rail

Uploaded by

rifathasan13Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

New Zealand Rail

Uploaded by

rifathasan13Copyright:

Available Formats

New Zealand Before 1982 the New Zealand railway was a government operation under The Railways Department

that had both commercial and social objectives, with social objectives often overriding the commercial goals. It was: (1) unprofitable; (2) very inefficient (3) production focused rather than customer focused; (4) relatively lacking in commercial management skills; and (5) ill prepared to meet potential competition. At the same time, pressure was growing to reform the freight transport industry by allowing trucking companies a greater access to the long haul market. In 1982 a process began to reform the railway system and in July 1993 New Zealand Rail Limited was sold to a consortium of New Zealand and foreign investors. The reform and restructuring of the New Zealand railway system proceeded in multiple, well-managed steps to final conveyance. New Zealand Rail has achieved dramatic improvements in productivity, financial performance, and customer service. Staff levels have fallen by over 75 percent since 1983 alongside improvement in staff productivity of over 200 percent leading to halving of the real cost per gross ton kilometer (GTK) and as a result currently it is one of the few railways in the world to be making a profit in a deregulated environment. Rate reductions in comparison with those of New Zealands other SOEs over the same period are also significant. The lessons learned from the New Zealand experience with railway privatization contain valuable guidelines for the railway privatization process. The main lessons are summarized below: Canada Canada has a unique rail industry structure that is dominated by two giant parallel rail systems one privately owned (Canadian Pacific Railway) (CP) and one publicly owned (Canadian National Railway) (CN) competing with each other for freight traffic. These two transcontinental carriers account for 89 percent of main and secondary lines in the country, while 23 other rail carriers operate in one or more of Canadas 10 provinces. Sixteen of the 25 carriers in the country are under federal jurisdiction, while 9 are under provincial jurisdictions. Canadian railways have been relatively slow to restructure in the face of mounting challenges from both intermodal and international competitors. A marked contrast exists with the parallel restructuring activities within the United States, where the pace of rail transformation has been more rapid. While the reasons for this slower pace are many, they lie primarily in the framework for economic regulation within which Canadian railways operate. The specific competitive factors that compel railway restructuring are strong. They include cross-border intermodal competition as well as competition from national motor carriers and increasing international rail competition. Throughout the twentieth century, the structure of the Canadian rail industry has for the most part remained intact, while, at the same time, the transport markets served by Canadian rail carriers have changed radically. The structural changes that have taken place in Canada have followed rather than led the market. A clear set of objectives supported by the board and management is essential. Legacies from the past should be removed. In the case of New Zealand Rail, these legacies were: High debt levels and excess staff numbers. There should be a focus on commercial goals. To ensure the financial viability of the company and to promote maximum efficiency, the company must be able to focus exclusively on commercial objectives. A supportive corporate culture is essential. Management needs to operate as a team if the company is to be reformed successfully. Internal conflicts should be avoided. Goals should be communicated to staff and unions. In this context, it is essential that all staff be seen to be treated equally. Core elements of business should be identified and noncore activities and assets should be disposed of.

Argentina When President Menem took office in July 1989, FA was losing US$1.3 billion annually and was suffering from a long-term systemic decline. There was deterioration in the carriers rolling stock (half of the locomotive fleet was out of service), poor track conditions and pervasive slow orders (55 % of the track was in less than acceptable condition), and a high rate of fare evasion (30 to 50 %), particularly in the Buenos Aires commuter services. FA had become primarily a provider of employment benefits to its excess work force, and of low quality, unreliable services to shippers and passengers that had no transport alternatives. The carrier was increasingly subject to political pressures and was strongly influenced by unions, suppliers, and local government authorities that perceived it to be a free good. In addition, FA service had become increasingly unreliable and un safe. The working deficit by 1989 was US$2 million per day. Contributing factors to FAs decline included: (1) a production oriented culture that paid little attention to satisfying customer needs; (2) increasing competition from other modes, particularly from a privately owned and effectively operated road transport sector; and (3) weak railway management and poorly targeted investments. There was a progressive decline in traffic in all three businesses in which FA participated: freight, intercity passenger, and the Buenos Aires City commuter passenger services. The restructuring and concessioning of state-owned railways in Argentina took place over a remarkably short period of time, motivated by the need to curb deficit spending and hyperinflation. The process began in July 1989 with a small group of politically astute decision makers, a dedicated and politically resourceful staff of rail privatization experts and two ministers committed to reform used this authority effectively to restructure Ferrocarriles Argentinos (FA), the state-owned railway, into 14 marketable concessions and to offer these concessions to the private sector. The results of their efforts were profound. The structural organizational changes, the ownership changes, and the cultural changes realized in Argentina over a four-year period were more far-reaching and complete in their implementation than those in any other emerging market economy in recent years. Although transformation was not complete at the time of this writing, and uncertainties remain about the success that new private operators (particularly the freight concessionaires) may have over the long term, the country has made a remarkable start in the effective private sector operation of its railway system. The lessons learned from the precedents set in Argentina, in consessioning its railways to private and public/private operators are those of expedient, creative, and forceful action in the face of entrenched political and economic opposition. First, it is clear from the Argentina experience that a concessionary approach to railway privatization can work. Other lessons have to do with the pre-selling and bid preparation necessary for concessioning. Valuable lessons can also be learned about the design of the concessions and also regarding the contestable and open processes needed to solicit best offers from potential concessionaires. There are lessons as well that concern the privatization management process through which a state-owned railway that generates huge annual losses and supports a large excess work force can be rapidly dismantled and sold (that is, concessioned). Finally, lessons can be drawn from Argentinas post -privatization experience with the enforcement of concessionary conditions and the design of a minimalist regulatory framework. Britain: Since 1948, railway services in Great Britain have been operated by the state as a single, vertically integrated business, including track maintenance as well as train operations, passenger and freight services, and virtually the whole range of supporting activities, although in the period since 1980 certain ancillary activities have been sold to the private sector. These included hotels, ferry services, and a substantial rail vehicle manufacturing business. The British Railways Board, as it eventually became in 1962 (known also as British Rail), was the successor to the big four regional private railway companies which had themselves been formed following a merger, in 1923, of 123 private railway companies of varying sizes that originated for the most part before the turn of the twentieth century. The pressures that led first to amalgamation and subsequently to nationalization of the railways gathered momentum over several decades.

After World War 2, British Government began to invest heavily on railway infrastructure. However, the program was undertaken with insufficient appreciation of the shrinking market role of the railways and without due regard to the low utilization of railway assets. The 1960s turned out to be the era of rationalization. In 1961, Dr. Richard Beeching was appointed Chairman of the British Railways Board. He brought forward a plan for reshaping the railways to reflect the declining use of many lines, stations, and freight facilities. The passenger railway sectors included Inter-City (operating high speed interurban services), Network South-East (covering the extensive London commuting and feeder routes), and Regional Railways (operating local feeder and cross-country services in England, Scotland, and Wales). A new company, European Passenger Services, was established by the Board to operate high speed rail passenger services through the Channel Tunnel to France and Belgium. A further wholly owned company, Union Railways Ltd., had been established to build a dedicated, highspeed passenger rail line between London and the Channel Tunnel. By 1993-94, British Rail operated a network of services extending over some 10,275 miles of route (23,450 track miles) including freight only, passenger only, and mixed with over 2,500 passenger stations. Locomotives included 1,400 diesels and 260 electrics of varying types. In 1993-94 the railways carried over 700 million passenger journeys, with an average distance of 25 miles. Privatization of the railways was first raised publicly as a policy objective by the then Secretary of State for Transport, Paul Channon, at the Conservative Party Conference in 1987. The policy was reaffirmed and fleshed out five years later, in the Conservative Partys 1992 Election Manifesto. The governments detailed proposals as to how privatization would be effected were published in July 1992, after the General Election. In between the first public, political reference to privatization and the publication of this policy statement, extensive deliberation took place within the Department of Transport. This deliberation was driven principally by the search for that elusive railway commodity, financial viability. United States After the restructure in 1970, railway sector has been gaining constantly rapid growth in income. In recent years the freight railroad system in the United States has moved away from subsidization for most types of service. US railway provides two types of service mainly, which are - large carriers and small local carriers. Two organizations are strongly related with US railway. Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) and Association of Association of American Railroads (AAR). Moreover, there are parts in small local services, like regional railroads, local railroads and switching and terminal. The great majority of small railroads had previously been operated as part of larger systems. Small rail roads are now competing with road trucks. Making a classification to the orientation its obvious to make their operation successful. New features include: 1. Privately-owned, common carrier railroad operations, 2. Class I subsidiaries, 3. Shipper-owned railroads, 4. Public supported, or subsidized, companies. Starting from 1970, US railway finished their restructuring in 1993. Step by step, phase by phase they reached their destiny. Freight and passenger service, they provide both. This restructure has made their lives easier and comfortable.

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- MRDocument238 pagesMRrifathasan13No ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Study On Mohammadi GroupDocument42 pagesA Study On Mohammadi Grouprifathasan13100% (2)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Survey QuestionnaireDocument19 pagesSurvey Questionnairerifathasan1375% (4)

- Analogy - 10 Page - 01 PDFDocument10 pagesAnalogy - 10 Page - 01 PDFrifathasan13No ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- EssarDocument3 pagesEssarrifathasan13No ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Brand MastersDocument26 pagesBrand Mastersrifathasan13No ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Building New Boxes WorkbookDocument8 pagesBuilding New Boxes Workbookakhileshkm786No ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Agricultural Economics 1916Document932 pagesAgricultural Economics 1916OceanNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Gender Ratio of TeachersDocument80 pagesGender Ratio of TeachersT SiddharthNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Marine Lifting and Lashing HandbookDocument96 pagesMarine Lifting and Lashing HandbookAmrit Raja100% (1)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Notifier AMPS 24 AMPS 24E Addressable Power SupplyDocument44 pagesNotifier AMPS 24 AMPS 24E Addressable Power SupplyMiguel Angel Guzman ReyesNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- DC Servo MotorDocument6 pagesDC Servo MotortaindiNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Deed of Assignment CorporateDocument4 pagesDeed of Assignment CorporateEric JayNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- An RambTel Monopole Presentation 280111Document29 pagesAn RambTel Monopole Presentation 280111Timmy SurarsoNo ratings yet

- Unit Process 009Document15 pagesUnit Process 009Talha ImtiazNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Phase 1: API Lifecycle (2 Days)Document3 pagesPhase 1: API Lifecycle (2 Days)DevendraNo ratings yet

- Use of EnglishDocument4 pagesUse of EnglishBelén SalituriNo ratings yet

- CIR Vs PAL - ConstructionDocument8 pagesCIR Vs PAL - ConstructionEvan NervezaNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Engineering Notation 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.: T Solution:fDocument2 pagesEngineering Notation 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.: T Solution:fJeannie ReguyaNo ratings yet

- Amerisolar AS 7M144 HC Module Specification - CompressedDocument2 pagesAmerisolar AS 7M144 HC Module Specification - CompressedMarcus AlbaniNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Dr. Eduardo M. Rivera: This Is A Riveranewsletter Which Is Sent As Part of Your Ongoing Education ServiceDocument31 pagesDr. Eduardo M. Rivera: This Is A Riveranewsletter Which Is Sent As Part of Your Ongoing Education ServiceNick FurlanoNo ratings yet

- Rebar Coupler: Barlock S/CA-Series CouplersDocument1 pageRebar Coupler: Barlock S/CA-Series CouplersHamza AldaeefNo ratings yet

- Lab Session 7: Load Flow Analysis Ofa Power System Using Gauss Seidel Method in MatlabDocument7 pagesLab Session 7: Load Flow Analysis Ofa Power System Using Gauss Seidel Method in MatlabHayat AnsariNo ratings yet

- Supergrowth PDFDocument9 pagesSupergrowth PDFXavier Alexen AseronNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- 1SXP210003C0201Document122 pages1SXP210003C0201Ferenc SzabóNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 185449, November 12, 2014 Del Castillo Digest By: DOLARDocument2 pagesG.R. No. 185449, November 12, 2014 Del Castillo Digest By: DOLARTheodore DolarNo ratings yet

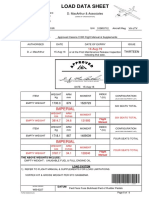

- Load Data Sheet: ImperialDocument3 pagesLoad Data Sheet: ImperialLaurean Cub BlankNo ratings yet

- BS 8541-1-2012Document70 pagesBS 8541-1-2012Johnny MongesNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Fidp ResearchDocument3 pagesFidp ResearchIn SanityNo ratings yet

- Executive Summary - Pseudomonas AeruginosaDocument6 pagesExecutive Summary - Pseudomonas Aeruginosaapi-537754056No ratings yet

- Powerpoint Presentation: Calcium Sulphate in Cement ManufactureDocument7 pagesPowerpoint Presentation: Calcium Sulphate in Cement ManufactureDhruv PrajapatiNo ratings yet

- Pneumatic Fly Ash Conveying0 PDFDocument1 pagePneumatic Fly Ash Conveying0 PDFnjc6151No ratings yet

- Catalogo AWSDocument46 pagesCatalogo AWScesarNo ratings yet

- CDKR Web v0.2rcDocument3 pagesCDKR Web v0.2rcAGUSTIN SEVERINONo ratings yet

- Water Hookup Kit User Manual (For L20 Ultra - General (Except EU&US)Document160 pagesWater Hookup Kit User Manual (For L20 Ultra - General (Except EU&US)Aldrian PradanaNo ratings yet

- Mat Boundary Spring Generator With KX Ky KZ KMX KMy KMZDocument3 pagesMat Boundary Spring Generator With KX Ky KZ KMX KMy KMZcesar rodriguezNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)