Professional Documents

Culture Documents

HTA Paroxistica

Uploaded by

Emil Eduardo Julio RamosOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

HTA Paroxistica

Uploaded by

Emil Eduardo Julio RamosCopyright:

Available Formats

the renal consult

http://www.kidney-international.org & 2008 International Society of Nephrology

Paroxysmal hypertension in a 48-year-old woman

Jennifer Hunt1 and Julie Lin1

1

Renal Division, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Womens Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA

CASE PRESENTATION A 48-year-old woman was referred for a second opinion regarding paroxysmal hypertension. At the time of referral, she had an 18-month history of acute hypertensive crisis necessitating hospitalization. She had already undergone evaluation by primary care and endocrinology prior to this presentation. Prior to 18 months ago, she had no history of hypertension and her past medical history was only significant for two previous pregnancies, neither of which was accompanied by hypertension. She described herself as healthy and exercised daily prior to onset of these hypertensive attacks. She generally felt well rested. She saw her primary care physician regularly for health care maintenance and reported that her blood pressure prior to 18 months ago usually ranged from 110 to 120 mm Hg systolic, with a heart rate of 6070 beats per minute. She had no family history of hypertension. She was divorced and had two children. She did not smoke, drank one to two cups of coffee per day, drank three to four glasses of wine in the evenings, denied illicit drug use, and had no known drug allergies. At the time of our initial evaluation, she was taking atenolol 25 mg daily as prescribed by her primary care physician. She denied use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, vitamins, herbals, or other over the counter medications.

Beginning 18 months ago, she described her hypertensive episodes as sudden, unprovoked, unrelated to stress or panic, and accompanied by various symptoms including headache, nausea, tremors, and diarrhea. She described an accompanying sense of dread or panic though only after the other symptoms manifested. She was not aware that these episodes included hypertension until she sought care in a local

Correspondence: Julie Lin, Renal Division, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Womens Hospital, Harvard Medical School, 75 Francis Street, Boston, Massachusetts 02115, USA. E-mail: jlin11@partners.org Kidney International (2008) 74, 532535; doi:10.1038/KI.2008.6; published online 27 February 2008 Received 10 April 2007; revised 7 November 2007; accepted 13 November 2007; published online 27 February 2008 532

emergency department and found her blood pressure to be 260/140 mm Hg. She had seen a medical professional at least a dozen times during those 18 months and was hospitalized at least three times for a period of 3 to 4 days while undergoing examination for secondary causes of hypertension. In recent months, she had noted an acceleration in the frequency of the episodes from once or twice per month to three to four times per week. The patient reported that she often left the emergency room with improved but still elevated blood pressure in the 160/90 range. Her physicians tried multiple single-agent medications, including amlodipine 5 mg daily, HCTZ 25 mg daily, metoprolol 100 mg daily, and labetolol 200 mg twice daily, which were variably titrated upwards during hypertensive episodes. Between attacks, her blood pressure was 100120 mm Hg systolic or lower; however, she experienced symptomatic hypotension between the episodes necessitating that the medications be reduced or stopped entirely. The results of multiple plasma and 24-h urine tests, including plasma renin and aldosterone, urine catecholamines, and 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) (at least one of which was collected during a hypertensive episode) were reviewed by us and were normal and not suggestive of pheochromocytoma, primary aldosteronism, or carcinoid syndrome (Table 1). A fundoscopic examination documented from at least one of her emergency room visits was stated as normal. She had also undergone an abdominal computed tomographic scan that demonstrated no adrenal masses and normal appearing kidneys. An echocardiogram performed a few months prior to our evaluation, however, did have evidence of concentric left ventricular hypertrophy. On examination, she was a healthy-appearing woman in no distress. Her blood pressure was 153/99 mm Hg with a pulse of 63, she weighed 138 pounds (62.6 kg) with a height of 65.5 inches (166 cm), and her body mass index was 22.5 kg m2. Her physical examination was unremarkable. She did not have enlarged tonsils or any craniofacial or soft tissue abnormalities. No thyroid abnormalities, skin changes, or abdominal bruits were detected. Fundoscopic examination was unremarkable. A urinalysis was normal and urine microscopy was negative. Electrolytes were unremarkable showing creatinine at 0.7 mg per 100 ml and serum potassium at 3.9 mg per 100 ml. On further questioning with regard to psychological stressors, she said that has been divorced for 5 years and had a history of physical and emotional abuse by her

Kidney International (2008) 74, 532535

J Hunt and J Lin: Paroxysmal hypertension in a 48-year-old woman

the renal consult

ex-husband. She reported that she had been in psychotherapy for several years with a non-physician psychotherapist and was not on any psychiatric medications. She is a single mother of two school-aged children and currently attempting to start a new business. She felt stress with regard to her business, as it would be her primary means of income. She was open about her alcohol intake, but denied signs or symptoms consistent with dependence. Her alcohol intake of 34 glasses of wine per day has been unchanged for 10 years and was conrmed by previous primary care notes in the medical record. When questioned about her specic activities and frame of mind on the day or two preceding a number of her recent attacks, she adamantly denied overt anxiety, fear, or emotional distress. In fact, one of the most recent attacks occurred on a weekend while she was at the beach relaxing with her oldest daughter and enjoying a pleasant afternoon.

CLINICAL DIAGNOSIS

CLINICAL FOLLOW-UP

We continued atenolol, added doxazosin 1 mg twice per day, and added paroxetine 10 mg per day to her medical regimen. She came for follow-up 3 weeks later and reported no new hypertensive crisis since starting the new regimen. Her usual systolic blood pressure was around 110 mm Hg. She still experienced systolic blood pressures in the range of 150 to 160 mm Hg, but only when exercising, an activity that she recently resumed. A telephonic interview 4 months later revealed no further hypertensive episodes and a maximum systolic blood pressure of 130 mm Hg, even while exercising. She continued to drink 34 glasses of wine per day, and the psychosocial stressors of starting a business and difcult interactions with her ex-husband were unchanged at follow-up.

DISCUSSION

She was clinically diagnosed with pseudopheochromocytoma.

Table 1 | Laboratory results

Electrolytes Na: 134 mmol l1 (ref. 136142 mmol l1) K: 3.9 mmol l1 (ref. 3.55.0 mmol l1) Cl: 98 mmol l1 (ref. 98108 mmol l1) CO2: 27 mmol l1 (ref. 2332 mmol l1) BUN: 8 mg per 100 ml (ref. 925 mg per 100 ml) Creatinine: 0.7 mg per 100 ml (ref. 0.71.3 mg per 100 ml) Other plasma tests Plasma renin: 1.5 ng ml1 (ref. 0.21.6 ng ml1) Plasma aldosterone: 27.9 ng per 100 ml (ref. 431 ng per 100 ml) TSH 1.6 mIU l1 (normal 0.55.0) Urinalysis and urine microscopy Specific gravity, 1.004 pH 6.5 No albumin, ketones, or nitrites RBC/hpf: 35 WBC/hpf: none Casts: none

24-h urine collection Total volume, 2650 ml Na: 130 mmol (ref. 75200 mmol) K: 53 mmol (ref. 4080 mmol) Creatinine: 1193 mg (ref. 8001800 mg) Aldosterone: 13.8 mcg (ref. 625 mcg) Epinephrine: 8 mcg (ref. 025 mcg) Norepinephrine: 61 mcg (ref. 0100 mcg) Dopamine: 231 mcg (ref. 60440 mcg) Free cortisol: 2.7 mcg (ref. 045 mcg) Normetanephrines: 419 mcg (ref. 50650 mcg) Metanephrines: 117 mcg (ref. 30350 mcg) Vanillyl mandelic acid (VMA): 2.1 mg (07 mg) 5-HIAA: 4 mg (ref. 08 mg)

Other urine tests Urine toxicology screen: negative

In the clinical evaluation of the patient with a recent onset of paroxysmal hypertension, secondary causes of hypertension must be investigated. The most common causes of secondary hypertension, whether sustained or episodic, include renovascular disease, primary aldosteronism, renal parenchymal disease, obstructive sleep apnea, hyperthyroidism, Cushings syndrome, and pheochromocytoma.1 The syndrome of a catecholamine-secreting pheochromocytoma (Table 2) is one of the most recognized form of secondary hypertension, although among the rarest form ultimately diagnosed with only 0.10.6% of hypertension cases attributed to this etiology.2 Pheochromocytoma must be considered, however, as it is potentially lethal when unrecognized as it can lead to cerebral vascular accidents or myocardial infarctions as a consequences of the effects of secreted catecholamines.3 The term pseudopheochromocytoma has been used to describe paroxysmal hypertension with a spectrum of signs and symptoms consistent with catecholamine excess, but in the absence of a clinical diagnosis of pheochromocytoma. It was used by Kuchel4 in 1981 to describe a hyperadrenergic form of essential hypertension with labile blood pressure, low conjugated catecholamines, and commonly associated with emotional triggers. He reinforced the predominance of overt emotionally provoked bouts of hypertension in this population in a 10-year retrospective analysis from 1998.5 Similarly in 1985, Takabatake et al.6 described a series of patients meeting these criteria. The term pseudopheochromocytoma has since been variably used in the literature to describe syndromes of

Table 2 | Common symptoms associated with pheochromocytoma

Sustained or episodic hypertension Headache Diaphoresis Palpitations Pallor Nausea Flushing Psychological symptoms 533

BUN, blood urea nitrogen; 5-HIAA, 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid; hpf, high-power field; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone.

Kidney International (2008) 74, 532535

the renal consult

J Hunt and J Lin: Paroxysmal hypertension in a 48-year-old woman

paroxysmal hypertension that may include biochemical evidence of catecholamine excess in the absence of an identiable tumor. Anti-Parkinsonian drugs and obstructive sleep apnea have been described to cause elevations in plasma catecholamines resulting in labile hypertension.7,8 Preeclampsia resulting in an elevation of urinary catecholamine can also mimic pheochromocytoma.9 There is also a description of a state of catecholamine excess indirectly resulting from a non-catecholamine-secreting tumor as pseudopheochromocytoma.10 More consistent with Kuchels original description of pseudopheochromocytoma, however, Mann and co-workers used the term to describe paroxysmal hypertension in the absence of biochemical catecholamine excess, but Mann11 also limited the description to the absence of immediately identiable panic or emotional distress. Consistent with the description by Mann, we will limit the use of the term pseudopheochromocytoma in the context of this discussion to describe a syndrome of unexplained paroxysmal hypertension without biochemical evidence of catecholamine excess. Borrowing from that description, paroxysmal hypertension differs from panic attack in that there is a clear relationship between blood pressure elevation and stress or emotional distress with panic attacks.11 Therefore, in addition to the otherwise unexplained paroxysms of hypertension, we will specify that pseudopheochromocytoma should exclude provocation from emotional distress as an underlying etiology. In the case described here, paroxysmal hypertension was the predominant feature, and causes of paroxysmal hypertension with respect to catecholamine excess are presented in Table 3. Several of these etiologies were ruled out in our patient by the medical history, laboratory, and imaging studies. Although she did not have a formal sleep study, she did not have a history or physical exam suggestive of sleep apnea. As she was evaluated for catecholamine excess both during and between hypertensive crisis, paroxysmal hypertension from catecholamine excess states as listed in Table 3A was ruled out. A differential diagnosis for paroxysmal hypertension without catecholamine excess could be summarized in Table 3B. She adamantly denied preceding anxiety

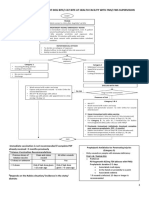

Table 3 | Paroxysmal hypertension and catecholamine excess states

A. Paroxysmal hypertension associated with plasma or urinary catecholamine excess Pheochromocytoma Obstructive sleep apnea Anti-Parkinsonian drugs Cocaine use Baroreflex failure B. Paroxysmal hypertension in the absence of biochemical catecholamine excess Anxiety state (panic attack) Thyrotoxicosis Pseudopheochromocytoma Alcohol withdrawal Carcinoid syndrome 534

states or panic attacks, although she did become emotionally distressed when a hypertensive crisis was underway. Thyrotoxicosis and carcinoid were ruled out by laboratory analysis, and there was no history or evidence of alcohol withdrawal. Pseudopheochromocytoma (as dened above) was therefore diagnosed and treatment started. Literature suggests the treatment of pseudopheochromocytoma consists of a combination of b- and a1-adrenergic blockade along with psychopharmacologic therapy.11 This strategy of dual adrenergic blockage in pseudopheochromocytoma is supported by a study by Hamada et al., which demonstrated that the hemodynamic response to a valsalva in a population with pseudopheochromocytoma was much greater than that of the population with pheochromocytoma. Hemodynamic monitoring implied a hyperactivity of both the b- and a1-adrenergic receptor functions in pseudopheochromocytoma. This is in contrast to the population with true pheochromocytoma, which showed a blunted response of both adrenergic systems due to desensitization associated with chronic catecholamine excess. Administration of a b- and a1-blocker to the population with pseudopheochromocytoma resulted in the normalization of hemodynamics and is thought to be the mechanism of symptom relief.12 A less well-described and certainly perplexing aspect of pseudopheochromocytoma is the absence of overt emotional distress yet reliance on psychopharmacologic therapy in addition to adrenergic blockade. Our patient was seeing a non-physician psychotherapist; however, she was not receiving psychopharmacologic therapy. She did admit to psychological stressors such as a history of abuse, starting a new business, and fear of failure on behalf of her children, however, she adamantly denied overt panic attacks or emotional distress preceding her attacks. Mann11 did identify repression of emotions, however, as a common feature of patients included in his case series. In this context, antidepressants and anxiolytics are aimed at treating a possible subclinical psychological disorder that predisposes a certain population to these paroxysms of hypertension. There is only anecdotal evidence regarding the type or duration of this aspect of therapy, but resolution of symptoms with treatment often occurs in a short period of time in this selected population, as in our patient. After an 18-month history of new onset, unprovoked paroxysmal hypertension treated with several other agents to the point of hypotension between attacks, ultimately only the combination of relatively low-dose b-blockade, a1-blockade, and an antidepressant produced a rapid and complete resolution of her symptoms in the absence of any change in other parameters such as her alcohol intake or psychosocial stressors.

SUMMARY

In conclusion, clinicians should recognize secondary causes of paroxysmal hypertension specically with regard to the patient suspected of having pheochromocytoma. The absence of a detectable catecholamine excess state in cases of

Kidney International (2008) 74, 532535

J Hunt and J Lin: Paroxysmal hypertension in a 48-year-old woman

the renal consult

paroxysmal hypertension has a narrow differential, and one should not overlook the diagnosis of pseudopheochromocytoma especially in the absence of overt anxiety states. The syndrome of pseudopheochromocytoma as described here can be effectively treated and long-term management achieved with the combined regimen of b- and a1-adrenergic blockade along with psychopharmacologic therapy.

REFERENCES

1. Hall WD. Resistant hypertension, secondary hypertension, and hypertensive crises. Cardiol Clin 2002; 20: 281289. 2. Lenders JW, Eisenhofer G, Mannelli M et al. Phaeochromocytoma. Lancet 2005; 366: 665675. 3. Lenders JW, Pacak K, Walther MM et al. Biochemical diagnosis of pheochromocytoma: which test is best? JAMA 2002; 287: 14271434. 4. Kuchel O, Buu NT, Hamet P et al. Essential hypertension with low conjugated catecholamines imitates pheochromocytoma. Hypertension 1981; 3: 347355.

Kuchel O. Increased plasma dopamine in patients presenting with the pseudopheochromocytoma quandary: retrospective analysis of 10 years experience. J Hypertens 1998; 16: 15311537. 6. Takabatake T, Yamamoto Y, Ohta H et al. Blood pressure variability and hemodynamic response to stress in patients with paroxysmal elevation of blood pressure. Clin Exp Hypertens A 1985; 7: 235242. 7. Duarte J, Sempere AP, Cabezas C et al. Pseudopheochromocytoma in a patient with Parkinsons disease. Ann Pharmacother 1996; 30: 546. 8. Hoy LJ, Emery M, Wedzicha JA et al. Obstructive sleep apnea presenting as pseudopheochromocytoma: a case report. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004; 89: 20332038. 9. Shah BR, Gandhi S, Asa SL et al. Pseudopheochromocytoma of pregnancy. Endocr Pract 2003; 9: 376379. 10. Hocqueloux L, Mortier E, Cabane J. Pseudopheochromocytoma: an unrecognized cancer-associated syndrome? Arch Intern Med 1998; 158: 13811382. 11. Mann SJ. Severe paroxysmal hypertension (pseudopheochromocytoma): understanding the cause and treatment. Arch Intern Med 1999; 159: 670674. 12. Hamada M, Shigematsu Y, Mukai M et al. Blood pressure response to the valsalva maneuver in pheochromocytoma and pseudopheochromocytoma. Hypertension 1995; 25: 266271.

5.

Kidney International (2008) 74, 532535

535

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Patient Centered Pharmacology Tindall William N Sedrak Mona M Boltri John M SRG PDFDocument575 pagesPatient Centered Pharmacology Tindall William N Sedrak Mona M Boltri John M SRG PDFTedpwer100% (3)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Alzheimer's Disease and Oral CareDocument5 pagesAlzheimer's Disease and Oral CarebkprosthoNo ratings yet

- CAUTIDocument46 pagesCAUTImahesh sivaNo ratings yet

- Introduction to the History and Development of Medical TechnologyDocument23 pagesIntroduction to the History and Development of Medical TechnologyAnne TGNo ratings yet

- Case Study - Lt1Document9 pagesCase Study - Lt1Diane E.No ratings yet

- AHA Guidelines On Prevention of Rheumatic FeverDocument4 pagesAHA Guidelines On Prevention of Rheumatic FeverEmil Eduardo Julio RamosNo ratings yet

- Nuevos Tto Anemia IRCDocument8 pagesNuevos Tto Anemia IRCEmil Eduardo Julio RamosNo ratings yet

- Atorvastatina-IRC y DialisisDocument11 pagesAtorvastatina-IRC y DialisisEmil Eduardo Julio RamosNo ratings yet

- Acute Renal Failure and SepsisDocument11 pagesAcute Renal Failure and SepsisYesid OlidenNo ratings yet

- RelapseDocument10 pagesRelapseEmil Eduardo Julio RamosNo ratings yet

- Handover Policy VERSION 5 - JULY 2021 FINALDocument11 pagesHandover Policy VERSION 5 - JULY 2021 FINALMarianne LayloNo ratings yet

- Comprehensive Cancer Care CenterDocument40 pagesComprehensive Cancer Care CenterKINJALNo ratings yet

- Kern AttestationDocument120 pagesKern AttestationBakersfieldNowNo ratings yet

- COVID-19 Staff Vaccine BriefingDocument5 pagesCOVID-19 Staff Vaccine BriefingtasialalalaNo ratings yet

- Jennifer Tripodi ResumeDocument2 pagesJennifer Tripodi Resumeapi-242986811No ratings yet

- Mindsets Matter: A New Framework For Harnessing The Placebo Effect in Modern MedicineDocument24 pagesMindsets Matter: A New Framework For Harnessing The Placebo Effect in Modern MedicineΑποστολος ΜιχαηλιδηςNo ratings yet

- History Taking Checklist.Document4 pagesHistory Taking Checklist.لو ترىNo ratings yet

- Nursing Impact On Maternal and Infant Mortality in The United States.Document7 pagesNursing Impact On Maternal and Infant Mortality in The United States.boniface mogisoNo ratings yet

- Medical EthicsDocument27 pagesMedical Ethicspriyarajan007No ratings yet

- The Significant Association Between Maternity Waiting Homes Utilization and Perinatal Mortality in Africa: Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument6 pagesThe Significant Association Between Maternity Waiting Homes Utilization and Perinatal Mortality in Africa: Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisTegenne LegesseNo ratings yet

- Making Occlusion 2Document7 pagesMaking Occlusion 2Ali QawasNo ratings yet

- WHO Health Promotion Glossary: New TermsDocument6 pagesWHO Health Promotion Glossary: New TermsBrendan MaloneyNo ratings yet

- Planning of Nursing ProcessDocument14 pagesPlanning of Nursing ProcessJoviNo ratings yet

- B-2211 Implementation of DCI Revised B.D.S. CourseDocument17 pagesB-2211 Implementation of DCI Revised B.D.S. CourseShital KiranNo ratings yet

- OPD Form IhealthcareDocument2 pagesOPD Form IhealthcareSanjay PatilNo ratings yet

- ENGLISH SPM Section C 2Document4 pagesENGLISH SPM Section C 2Mohamad NuraizatNo ratings yet

- Heart Disease in PregnancyDocument5 pagesHeart Disease in PregnancyAngeliqueNo ratings yet

- Individual Family Health Insurance ApplicationDocument7 pagesIndividual Family Health Insurance ApplicationsundarmjkNo ratings yet

- 21 CFR 1271 Human Cells Tissues and Cellular and Tissue-Based Products PDFDocument27 pages21 CFR 1271 Human Cells Tissues and Cellular and Tissue-Based Products PDFjgregors8683No ratings yet

- mmc1 PDFDocument48 pagesmmc1 PDFAnthony LachNo ratings yet

- MANAGING DOG/CAT BITES AT HEALTH FACILITYDocument5 pagesMANAGING DOG/CAT BITES AT HEALTH FACILITYleo89azman100% (1)

- Pedo Revision For Part 1Document17 pagesPedo Revision For Part 1asadNo ratings yet

- Lancaster, John E. - Newcastle Disease - A ReviDocument201 pagesLancaster, John E. - Newcastle Disease - A RevipaigneilNo ratings yet

- Crisis Management Covid 19Document22 pagesCrisis Management Covid 19jon elleNo ratings yet

- 3 - Full Pulpotomy With Biodentine in Symptomatic Young Permanent Teeth With Carious Exposure PDFDocument6 pages3 - Full Pulpotomy With Biodentine in Symptomatic Young Permanent Teeth With Carious Exposure PDFAbdul Rahman AlmishhdanyNo ratings yet