Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Assessing E-Portfolios Through A Constructivist Lens

Uploaded by

gilliansudlowOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Assessing E-Portfolios Through A Constructivist Lens

Uploaded by

gilliansudlowCopyright:

Available Formats

0

Running Head: Assessing E-portfolios through a Constructivist Lens

Assessing E-portfolios through a Constructivist Lens

Assignment 1 ETEC 530 Gillian Sudlow The University of British Columbia Samson Nashon

Running Head: Assessing E-portfolios through a Constructivist Lens

Introduction

Constructivism requires a learner-centred environment in which the learner actively constructs knowledge through the process of authentic tasks and assessment. Electronic portfolios (EPs) can be effective learning and assessment tools that align with constructivist epistemology if all stakeholders remain cognizant of their primary goal to capture the learning process and encourage students to engage in self-reflection as they seek to discover what and how they learn. By examining EPs through a constructivist lens, one can see their alignment with constructivist epistemology as they enable learners to use technology as a cognitive tool to actively construct knowledge, create a learner-centred environment through authentic tasks, and authentically assess the learning process.

What is an Electronic Portfolio?

An Electronic portfolio (EP) is a digital collection of work, or artifacts, selected and reflected upon by the learner that tells the story of the learners progress and change over time in their efforts to achieve learning goals (Wang, 2007; Barrett, 2005, 2007). Technological affordances of EPs provide many advantages over traditional paper-based portfolios, ultimately bringing them in closer alignment to the goals of constructivism. A digital platform allows learners to include artifacts and reflections in a variety of media formats including text, images, audio and video (Barrett, 2005; 2007), thus supporting a variety of learning styles and enhancing student engagement. Digital formats allow students to archive data and change and update their portfolios to reflect changes in their construction of knowledge. The use of hyperlinks allows learners to make connections among their collection of artifacts as well as to learning outcomes goals or standards; such links support deep learning and metacognition along with making assessment more authentic (Barrett, 2005, 2007; Wang, 2007). Many digital platforms also afford collaboration with

Running Head: Assessing E-portfolios through a Constructivist Lens

peers and teachers enabling social learning and social negotiation of meaning through reciprocal feedback. The process of using digital technologies to create and organize artifacts using an electronic medium is an authentic task in itself as competencies with ICT (Information and Computer Technology) skills reflect real world tasks. Moreover, As learners create their own electronic portfolios, their unique voice should be evident from navigating the portfolios and reading the reflection on the screen. In an electronic portfolio, the ability to add multimedia elements expands the definition of voice within that rhetorical construct. (Barrett, 2005, p.9) Finally, because of their digital format, EPs lend themselves to all modes of course delivery classroom, blended and online. While using technology to create a portfolio can be a motivating factor and engage learners, it can also be a barrier in regards to learner access and technical competency (Barrett, 2005). Access to technology is becoming less of a factor, even in remote and economically depressed communities as internet access is becoming more widespread and as more open-source technologies become available; however, it should still be a consideration of the teacher before deciding to use EPs. Learner competency with ICT skills, however, may vary within a class. To minimize technical competencies from becoming a barrier to learning, teachers should survey students before beginning the process of EPs to assess their level of competency and then provide appropriate scaffolding. In conjunction with teacher scaffolding, learners should be encouraged to solve and trouble-shoot technical problems on their own and look for peer support within their learning community, thus fostering both autonomous and social learning (Chau & Cheng, 2010).

E-Portfolios as Authentic Tasks

Constructivism dictates that learners take an active role in their construction of knowledge through participation in authentic tasks. Learners take ownership of their portfolios and thus their own learning through goal setting, monitoring progress, reflecting on what theyve learned, and receiving and giving

Running Head: Assessing E-portfolios through a Constructivist Lens

feedback. The assembly of an EP requires a leaner to not only create, select and organize artifacts in a digital platform, but also to reflect upon, evaluate through self and peer assessment and synthesize their learning experience throughout the entire process (Barrett, 2007; Chau & Cheng, 2010; Clark & Adamson, 2009; Wang, 2007). The artifacts that a learner selects to include in their EPs are meant to represent evidence of their learning experience and progress over time (Barrett, 2007). While the assembly of such evidence is in itself an authentic task, the artifacts which constitute the evidence could themselves be the products of authentic tasks. Artifacts are coursework, projects and assignments that have been done as part of a class. For example, an artifact could be a multi-media project, resulting from a project-based learning task, or an essay response outlining a solution to an ill-structured problem. Whatever the artifact, the evidence of learning is not complete without an accompanying reflection. Researchers agree that the reflective process of creating an EP is critical to achieving the constructivist goals of developing an understanding of how one learns to become an independent and life-long learner (Barrett, 2005; 2007; Chau & Cheng, 2010; Clark & Adamson, 2009; Paulson & Paulson, 1994). Reflections in an EP can include rationales for the inclusion of an artifact, personal assessment and explanations of how the artifact represents their achievement of learning goals or standards, responses to peer and teacher feedback, and personal responses detailing the learning process and experience of creating the artifact (Chau & Cheng, 2010; Barrett, 2007). Reflection is a means to become aware of ones strengths and weaknesses, monitor progress, employ repair strategies where needed, modify goals and recognize opportunities for further improvement (Chau & Cheng, 2010). The process of reflection supports deep learning and metacognition as it encourages students to think more about how they learn rather than what they learn, emphasizing the learning process over the learning product (Barrett, 2007; Clark & Adamson, 2010).

Running Head: Assessing E-portfolios through a Constructivist Lens

Viewing an EP as a sum of its parts, it is clearly more than a learning tool or strategy; it is a constructivist learning environment in which the learner is in control. Within this environment, learners learn by doing, attempt to reconcile new knowledge with existing cognitive structures, acquire new skills, share understandings with peers and teachers and construct shared knowledge. By placing learners in the centre of the learning task, EPs reduce the role of the teacher.The teacher supports the process of creating an EP by providing students with regular feedback, scaffolding tasks when needed and providing extra help only when requested. For an EP to remain in the control of the learner, it is important for the teacher to maintain the role of guide on the side or at most a coconstructor. Too much teacher intervention risks removing the locus of control from the learner and losing the authentic voice of the learner in the process of creation (Barrett, 2007). The setting of learning goals and tasks which provide the foundation for the artifacts and reflections of an EP can be a vulnerable point in the process where ownership and control can be usurped by the teacher. Such intervention is likely caused by a teachers concern over accountability in meeting institutional curriculum goals and standards. However, institutional accountability and learner control can both be accomplished through social negotiation and co-construction. With the teacher, learners can coconstruct learning goals and tasks, using institutional learning goals and achievement standards as a guide (Barrett, 2005; 2007; Paulson & Paulson, 1994). This process can also be used to ensure assessment practices remain authentic.

E-Portfolios as Authentic Assessment

Constructivism favours authentic assessment; assessment which is part of the learning process and based in the context of the learner and the learning environment. Unlike traditional assessment OF learning where assessment is viewed by the learner as something done to them, authentic assessment is assessment FOR learning and is a process in which the learner is directly involved (Barrett, 2005;

Running Head: Assessing E-portfolios through a Constructivist Lens

Paulson& Paulson, 1994). If an EP is to be an example of authentic learning, attempting to apply traditional standards would subvert the nature of the portfolio process by taking control and ownership away from the learner (Paulson & Paulson, 1994).Still, balancing the desire to provide an authentic learning experience for learners within a constructivist model and the need to satisfy institutional curricular standards can be a tenuous act, especially in regards to assessment.The challenge for us is to find electronic portfolio strategies that meet the needs of both the students, to support this deep learning, and to give the institution the information they need for assessment and reporting purposes. (Barrett, 2005, p.8)Paulson & Paulson (1994) contend that portfolios, if assessed according to the constructivist paradigm, can bring learners to the centre of the assessment process: The portfolio is a way of including students in the assessment process. It is a place where it is perfectly legitimate for the student to deliberately try to influence others beliefs in what they know. The portfolio is a way of changing the relationship between the student and the assessment process itself - to turn it upside down to make the student a full and active partner in his or her own learning and the assessment thereof including the design of the assessments that determine the standards and judgements that are reached. (p. 13) By bringing external institutional curriculum documents which set learning goals and objectives for student achievement into the classroom as a resource and a reference, students and teachers can define and interpret learning goals and how to achieve them by creating rubrics which adhere to the institutional standards. EPs can then be self, peer and teacher assessed using these rubrics. Used in this way, assessment becomes authentic and part of the learning task as the learner, with the support of peers and the teacher,makes the institutional standards operational (Clark & Adamson, 2009; Paulson & Paulson, 1994) while still maintaining control of the entire EP process from the selection of artifacts to reflection to assessment.

Running Head: Assessing E-portfolios through a Constructivist Lens

Conclusions

While there are numerous opportunities to lapse into traditional methods along the way, EPs can fulfill constructivist goals of learning, teaching and assessment if the focus remains on the learner and the learning process, not the end product. Throughout the entire process of creating an EP, from assembly to assessment, the learner must be placed at the centre. An EPs digital platform provides an engaging, flexible learner-centred environment while encouraging the acquisition of ICT skills and enabling metacognition and social learning. The artifacts and reflections included in EPs represent a series of authentic tasks within a larger authentic task of assembling, throughout which the learner is in full control. The reflections support metacognition by encouraging the learner to focus on and understand the process of his or her own learning. Finally, authentic assessment includes the learner while meeting the needs of the institution.

Running Head: Assessing E-portfolios through a Constructivist Lens

References:

Barrett, H. C. (2005). White paper: Researching electronic portfolios and learner engagement: The REFLECT initiative. Retrieved from http://electronicportfolios.com/reflect/whitepaper.pdf Barrett, H. C. (2007). Researching electronic portfolios and learner engagement: The REFLECT initiative. International Reading Association, 436-449. doi:10.1598/JAAL.50.6.2 Chau, J., & Cheng, G. (2010). Towards understanding the potential of e-portfolios for independent learning: A qualitative study. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 26(7), 932-950. Retrieved from http://www.ascilite.org.au/ajet/26/chau.htm Clark, W., & Jackie, A. (2009). Assessment of an eportfolio: Developing a taxonomy to guide the grading and feedback for personal development planning. Univesity of Cumbria, 3(1), 43-51. Retrieved from http://194.81.189.19/ojs/index.php/prhe/article/viewFile/33/31 Paulson, F. L., & Paulson, P. R. (1994). Assessing portfolios using the constructivist paradigm. Retrieved from http://www.eric.ed.gov/PDFS/ED376209.pdf Wang, S. (2007). Roles of students in electronic portfolio development. International Journal of Teaching and Learning, 3(2), 17-28. Retrieved from http://www.sicet.org/journals/ijttl/specialIssue/sywang.pdf

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- EPortfolio ProposalDocument7 pagesEPortfolio ProposalgilliansudlowNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Gsudlow Etec 522 Venture Pitch: 21st Century Online Professional DevelopmentDocument7 pagesGsudlow Etec 522 Venture Pitch: 21st Century Online Professional DevelopmentgilliansudlowNo ratings yet

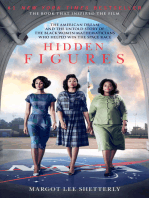

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Beyond The Classroom: Using A Blended Learning Environment To Teach Critical Thinking and Writing SkillsDocument23 pagesBeyond The Classroom: Using A Blended Learning Environment To Teach Critical Thinking and Writing SkillsgilliansudlowNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Is This Course A Community of PracticeDocument1 pageIs This Course A Community of PracticegilliansudlowNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Building Successful Learning Communities in A Blended Classroom: A Critical ReflectionDocument10 pagesBuilding Successful Learning Communities in A Blended Classroom: A Critical ReflectiongilliansudlowNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Learning and Writing Beyond The Traditional Classroom: Using Online Forums To Extend Learning in Adult Continuing Education Courses A Research ProposalDocument20 pagesLearning and Writing Beyond The Traditional Classroom: Using Online Forums To Extend Learning in Adult Continuing Education Courses A Research ProposalgilliansudlowNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Masiullah New CV Update...Document4 pagesMasiullah New CV Update...Jahanzeb KhanNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Orchestration and Arranging Lesson PlanDocument2 pagesOrchestration and Arranging Lesson Planapi-283554765No ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- g9 - Unit 4 - Street Art PDFDocument6 pagesg9 - Unit 4 - Street Art PDFapi-424444999No ratings yet

- Critique PaperDocument6 pagesCritique PaperRegie Mino BangoyNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Virtual Classroom Challenges and Coping MechanismsDocument30 pagesVirtual Classroom Challenges and Coping MechanismsJay PasajeNo ratings yet

- Microteaching - 2.4.18 (Dr. Ram Shankar)Document25 pagesMicroteaching - 2.4.18 (Dr. Ram Shankar)ramNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Semi-Detailed Lesson PlanDocument11 pagesSemi-Detailed Lesson PlanLenette AlagonNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- 1 Online MBA, Financial Times 2017Document36 pages1 Online MBA, Financial Times 2017veda20No ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Madrasah Education Program counters extremism in Mindanao through teaching respect and solidarityDocument1 pageMadrasah Education Program counters extremism in Mindanao through teaching respect and solidarityAbdulmajed Unda MimbantasNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- English 10 First Quarter Week 6Document4 pagesEnglish 10 First Quarter Week 6Vince Rayos Cailing100% (1)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- School Orientation On The Administration of The NCAE - AdvisersDocument33 pagesSchool Orientation On The Administration of The NCAE - AdvisersMarco Rhonel Eusebio0% (1)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- Cutand Paste Spell Phonics Picture Sorting Worksheets Blends Digraphs FREEDocument4 pagesCutand Paste Spell Phonics Picture Sorting Worksheets Blends Digraphs FREEKannybell BelleNo ratings yet

- A-My Little BrotherDocument6 pagesA-My Little BrotherOliver ChitanakaNo ratings yet

- EnglDocument64 pagesEnglBene RojaNo ratings yet

- Problem-Solving Techniques in MathematicsDocument24 pagesProblem-Solving Techniques in MathematicsNakanjala PetrusNo ratings yet

- BOI AUD - Admission - 2019 PDFDocument50 pagesBOI AUD - Admission - 2019 PDFsaurabhshubhamNo ratings yet

- 2015 Childhope Asia Philippines Annual ReportDocument24 pages2015 Childhope Asia Philippines Annual ReportchildhopeasiaNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Interim Guidelines On The Preparation, Submission, and Checking of School FormsDocument25 pagesInterim Guidelines On The Preparation, Submission, and Checking of School FormsMaria Carmela Rachel GazilNo ratings yet

- Chapter Four The Audio-Lingual MethodDocument6 pagesChapter Four The Audio-Lingual Methodapi-274521031No ratings yet

- Why temperament important in teaching & learningDocument2 pagesWhy temperament important in teaching & learningJay Ann RodrigoNo ratings yet

- Certification documentsDocument3 pagesCertification documentsDhealine JusayanNo ratings yet

- Section I - Program Information: BA/BASW Application For Field Education Practicum/PlacementDocument5 pagesSection I - Program Information: BA/BASW Application For Field Education Practicum/PlacementAnanta ChaliseNo ratings yet

- List of Proformas (PH.D.) : Proforma No. NameDocument29 pagesList of Proformas (PH.D.) : Proforma No. NameNaveen KishoreNo ratings yet

- ELC3222 Assessment 2 Task 1 (Proposal) - Self-Reflection & Honour Declaration FormDocument2 pagesELC3222 Assessment 2 Task 1 (Proposal) - Self-Reflection & Honour Declaration Formsunpeiting020408No ratings yet

- Improving The Teaching of Personal Pronouns Through The Use of Jum-P' Language Game Muhammad Afiq Bin IsmailDocument5 pagesImproving The Teaching of Personal Pronouns Through The Use of Jum-P' Language Game Muhammad Afiq Bin IsmailFirdaussi HashimNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Second Language Acquisition EssayDocument7 pagesSecond Language Acquisition EssayManuela MihelićNo ratings yet

- Participation in Co-Curricular Activities Enhances Students' Leadership SkillsDocument13 pagesParticipation in Co-Curricular Activities Enhances Students' Leadership SkillsUmi RasyidahNo ratings yet

- White FB 2 LP Weaving Le Revised 1Document12 pagesWhite FB 2 LP Weaving Le Revised 1api-600746476No ratings yet

- Lesson Plan: Learning Objectives: Targeted Competencies: Target Structures: DomainDocument2 pagesLesson Plan: Learning Objectives: Targeted Competencies: Target Structures: Domainsol heimNo ratings yet

- Phonics JVWX WednesdayDocument1 pagePhonics JVWX WednesdayRohayati A SidekNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)