Professional Documents

Culture Documents

What Is A Retained Placenta?

Uploaded by

Baharudin Yusuf RamadhaniOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

What Is A Retained Placenta?

Uploaded by

Baharudin Yusuf RamadhaniCopyright:

Available Formats

Retained placenta

Approved by the BabyCentre Medical Advisory Board Last reviewed: October 2012 Show references

Highlights

What is a retained placenta? What causes a retained placenta? What problems can a retained placenta cause? What happens if my third stage is taking too long? How is a retained placenta treated? Can I prevent a retained placenta in my next pregnancy?

What is a retained placenta?

If you have a retained placenta, part of the placenta or membranes will remain inside your uterus (womb) after your baby is born. This happens during the third stage of labour. The third stage of labour is when the placenta and membranes are delivered. You can opt for a physiological (natural) third stage or a managed third stage. You'll be able to discuss this with your midwife before the birth. A physiological third stage involves you delivering the placenta by pushing it out yourself. A managed third stage is when your midwife gives you an injection in your thigh, just as your baby is being born. This injection helps your uterus to contract down and push out the placenta and membranes. Having a managed third stage reduces the risk of heavy bleeding immediately after your baby is born. You'll be treated for retained placenta if your midwife suspects that any of the placenta or membranes remains attached to your uterus. Shell examine the placenta after youve delivered it, and most cases are picked up at this stage. Occasionally, theres a delay to the placenta being delivered at all. Your midwife will treat you if the placenta hasn't been delivered:

Within one hour of your baby's birth if you had a physiological third stage (about 13 per cent of cases). Within 30 minutes of your baby's birth if you had a managed third stage (less than five per cent of cases).

What causes a retained placenta?

The three main causes of a retained placenta are:

When the uterus stops contracting, or doesn't contract enough for the placenta to separate from the wall of your uterus. This is called uterine atony. When part or all of the placenta is stuck to the wall of your uterus and doesn't separate. This is called an adherent placenta. In rare cases this happens because the placenta has deeply embedded itself in the wall of your uterus. When the placenta comes away from the uterus, but becomes trapped behind a semiclosed cervix. This is called a trapped placenta.

If you have a full bladder it may prevent the placenta from being delivered. If necessary, your midwife may insert a catheter to drain your bladder. If the placenta has separated and is ready to come out, it will slide easily through your vagina. If it hasn't completely separated, or if the cord is very thin when your midwife pulls, it may break. If this happens, you can usually help to deliver the placenta by pushing with a contraction. However, occasionally the cervix closes too much to allow the placenta out. A small piece of placenta, connected to the main part of the placenta by a blood vessel, may have been left behind in the uterus (a succenturiate lobe). Your midwife will examine the placenta and membranes carefully after your baby is born to ensure that they are complete. If she notices a vessel leading to nowhere, this should alert her to the possibility of part of the placenta being retained. Sometimes, a part of the placenta may stick to a scar from a previous caesarean section. This is a serious condition called a placenta accreta. This should be picked up during your pregnancy. Then plans can be made for you to have your baby in an obstetric unit, where you'll have the right level of care.

What problems can a retained placenta cause?

After the placenta is delivered, your uterus should contract down to close off all the blood vessels inside the uterus. If the placenta only partially separates, the uterus can't contract properly, so the blood vessels inside will continue to bleed. If the managed delivery of the placenta takes longer than 30 minutes after the birth of your baby, your risk of heavy bleeding increases. Heavy bleeding in the first 24 hours after birth is known as primary postpartum haemorrhage (PPH). If fragments of placenta or membrane are retained, and your midwife or doctor miss this, it may cause heavy bleeding and infection later (secondary PPH). Try not to worry about this happening to you. It is rare and happens in less than one per cent of births.

What happens if my third stage is taking too long?

If the third stage is taking a while, you could try breastfeeding your baby or rubbing your nipples, to release the hormone oxytocin. This may cause your uterus to contract and help to expel the placenta. If you're sitting or lying down, you could try changing to a more upright position to allow gravity to help. If you chose a physiological third stage, you can switch to a managed third stage if the placenta doesn't come within an hour. Your midwife will give you an injection of an oxytoxic drug to make your uterus contract. She will then gently pull out the placenta. Following a managed third stage, if the placenta is retained, your midwife can give you another injection of an oxytocic drug. She may also try injecting oxytocin and saline into the umbilical vein of the umbilical cord. Or she may just wait a bit longer to see if it comes away on its own.

How is a retained placenta treated?

If the placenta still hasn't been delivered after you've had oxytocin and saline, your doctor may need to remove it by hand. You won't feel discomfort during this procedure, because an anaesthetist will numb the area for you. You may have a regional anaesthetic such as a spinal or epidural. You can ask for a general anaesthetic if you prefer. However, a general anaesthetic carries more risks for you. You also won't be able to breastfeed immediately after the procedure because the drugs will temporarily taint your breastmilk. Once the anaesthetic is working you'll be taken to the operating theatre. Your midwife or an assistant will lift your legs into stirrups (the lithotomy position). Then your doctor will gently insert her hand to remove the placenta and any remaining membranes from your uterus. You'll have intravenous antibiotics to prevent infection, and you may need more intravenous drugs to help your uterus to contract down. If you have prolonged, heavy bleeding in the days or weeks following the birth, your doctor may refer you for an ultrasound scan. This is to see if there are any fragments of placenta or membrane in your uterus. If any fragments remain, you'll be admitted to hospital so that they can be removed. This is called evacuation of retained products of conception (ERPC) and is carried out under a regional (spinal) anaesthetic or a general anaesthetic. You'll be given antibiotics to treat any infection which may have developed.

Can I prevent a retained placenta in my next pregnancy?

Unfortunately, there isn't much you can do to prevent it. If you had a retained placenta in a previous birth, you do have a higher risk of it happening again. Bear in mind that this doesn't mean it will happen.

You are more likely to have a retained placenta if your baby is premature. This may be because the placenta was designed to stay put for 40 weeks. So if you have another premature labour, it may happen again. However, if the cord snapped, or if your cervix closed too quickly after having the oxytocic injection, you may consider a physiological third stage with your next baby. By allowing the placenta to deliver naturally, you avoid the possibility of the cervix closing too quickly and trapping the placenta. Talk about your options with your midwife. The prolonged use of syntocinon (artificial oxytocin) during labour has been linked to retained placentas. You may have had this if your labour was induced or speeded up. Bear in mind that with your next baby you may not need these interventions at all. http://www.babycentre.co.uk/a562148/retained-placenta#ixzz2dhDB2ykD

You might also like

- Trauma Care Manual-CRC Press Ian Greaves (Editor), Sir Keith Porter (Editor), Jeff Garner (Editor) - (2021)Document595 pagesTrauma Care Manual-CRC Press Ian Greaves (Editor), Sir Keith Porter (Editor), Jeff Garner (Editor) - (2021)Silvio danteNo ratings yet

- 2021 Book InterventionalCriticalCareDocument490 pages2021 Book InterventionalCriticalCareAntonio Castillo100% (1)

- Post Abortion CareDocument35 pagesPost Abortion CareNatukunda DianahNo ratings yet

- Prolonged Labor and Labor InductionDocument28 pagesProlonged Labor and Labor InductionNovia RizqiNo ratings yet

- Obstetric Analgesia and Anesthesia OptionsDocument51 pagesObstetric Analgesia and Anesthesia OptionsHerbert David100% (1)

- Antepartum HaemorrhageDocument48 pagesAntepartum HaemorrhageDuncan JacksonNo ratings yet

- Pregnancy Induced Hypertension (PIH) Is ADocument14 pagesPregnancy Induced Hypertension (PIH) Is APaul John HipolitoNo ratings yet

- Reducing Right Breast DiscomfortDocument3 pagesReducing Right Breast DiscomfortLouel VicitacionNo ratings yet

- Anatomy & Physiology Mcqs Solved-1Document42 pagesAnatomy & Physiology Mcqs Solved-1Sana Rasheed100% (1)

- Retained PlacentaDocument23 pagesRetained PlacentaHalbar August Kanda0% (1)

- Relieve Numbness & Tingling with Ulnar Nerve Entrapment TreatmentDocument19 pagesRelieve Numbness & Tingling with Ulnar Nerve Entrapment TreatmentChristian SolihinNo ratings yet

- Multiple PregnancyDocument20 pagesMultiple PregnancyNurul Fahmiza TumiranNo ratings yet

- Postpartum BluesDocument6 pagesPostpartum BluesmiL_kathrinaNo ratings yet

- What Is Aseptic TechniqueDocument8 pagesWhat Is Aseptic TechniqueDiyana DalilaNo ratings yet

- Nilai Normal Tes Laboratorium dan Pemeriksaan Medis LengkapDocument2 pagesNilai Normal Tes Laboratorium dan Pemeriksaan Medis LengkapMegeon Seong100% (1)

- Nilai Normal Tes Laboratorium dan Pemeriksaan Medis LengkapDocument2 pagesNilai Normal Tes Laboratorium dan Pemeriksaan Medis LengkapMegeon Seong100% (1)

- Nilai Normal Tes Laboratorium dan Pemeriksaan Medis LengkapDocument2 pagesNilai Normal Tes Laboratorium dan Pemeriksaan Medis LengkapMegeon Seong100% (1)

- Nilai Normal Tes Laboratorium dan Pemeriksaan Medis LengkapDocument2 pagesNilai Normal Tes Laboratorium dan Pemeriksaan Medis LengkapMegeon Seong100% (1)

- Uterine Prolaps1Document6 pagesUterine Prolaps1Ginsha GeorgeNo ratings yet

- What Is Retained PlacentaDocument7 pagesWhat Is Retained PlacentaA Xiao Yhing TrancoNo ratings yet

- CASE ANALYSIS Ectopic Pregnancy Part 1Document10 pagesCASE ANALYSIS Ectopic Pregnancy Part 1Diane Celine SantianoNo ratings yet

- 35 - Retained PlacentaDocument11 pages35 - Retained Placentadr_asalehNo ratings yet

- Definition of Placenta PreviaDocument3 pagesDefinition of Placenta Previashan6ersNo ratings yet

- Incomplete Abortion: A Mini Case Study OnDocument22 pagesIncomplete Abortion: A Mini Case Study OnSunny MujmuleNo ratings yet

- Uterine AtonyDocument20 pagesUterine AtonyKpiebakyene Sr. MercyNo ratings yet

- DEFINITION: Abortion Is The Expulsion or Extraction From Its MotherDocument10 pagesDEFINITION: Abortion Is The Expulsion or Extraction From Its MothermOHAN.SNo ratings yet

- Gestational Diabetes Case PresentationDocument102 pagesGestational Diabetes Case Presentationkitten garciaNo ratings yet

- Case StudyDocument5 pagesCase StudyJui Perano100% (2)

- Augmentation of Labour: Nabhan A, Boulvain MDocument8 pagesAugmentation of Labour: Nabhan A, Boulvain MMade SuryaNo ratings yet

- Case StudyDocument19 pagesCase Studywella goNo ratings yet

- Preterm LabourDocument18 pagesPreterm LabourRutu RajNo ratings yet

- Case PresentationDocument50 pagesCase Presentationapi-19762967No ratings yet

- Aklan State University Nursing Readings on Pyloric StenosisDocument5 pagesAklan State University Nursing Readings on Pyloric Stenosisensoooooooooo100% (1)

- Mastitis Prevention and TreatmentDocument25 pagesMastitis Prevention and TreatmentGeetha SoundaryaNo ratings yet

- IUFD Guide: Causes, Diagnosis and Management of Intrauterine Fetal DemiseDocument2 pagesIUFD Guide: Causes, Diagnosis and Management of Intrauterine Fetal Demisenurseon0% (1)

- NVD With EpisiotomyDocument4 pagesNVD With EpisiotomySimran SimzNo ratings yet

- Amniotic Fluid Embolism (AFE)Document26 pagesAmniotic Fluid Embolism (AFE)sanjivdas100% (1)

- CPDDocument45 pagesCPDVijith.V.kumar100% (1)

- Intrauterine Growth Restriction IUGR: TH THDocument2 pagesIntrauterine Growth Restriction IUGR: TH THZahra AlaradiNo ratings yet

- Uterine Sub InvolutionDocument1 pageUterine Sub Involutionkrystle0875% (4)

- Polyhydraminos and OligohydraminosDocument11 pagesPolyhydraminos and OligohydraminosMelissa Catherine ChinNo ratings yet

- Complications of The Third Stage of LabourDocument6 pagesComplications of The Third Stage of LabourSong QianNo ratings yet

- Hydatidiform Mole Study GuideDocument4 pagesHydatidiform Mole Study GuideCarl Elexer Cuyugan AnoNo ratings yet

- Shoulder DystociaDocument22 pagesShoulder Dystociaamulan_aNo ratings yet

- MANAGING UMBILICAL CORD PROLAPSEDocument22 pagesMANAGING UMBILICAL CORD PROLAPSEYosuaH.KumambongNo ratings yet

- Everything You Need to Know About EpisiotomiesDocument18 pagesEverything You Need to Know About EpisiotomiesAnnapurna DangetiNo ratings yet

- 3 - Diagnosis of PregnancyDocument5 pages3 - Diagnosis of PregnancyM7 AlfatihNo ratings yet

- Antenatal Case ReportDocument20 pagesAntenatal Case Reportpenppen100% (2)

- Abnormalities of Amniotic Fluid: Presented by Ms. K.D. Sharon Final Year MSC (N) Obstetrics and Gynaecology NursingDocument32 pagesAbnormalities of Amniotic Fluid: Presented by Ms. K.D. Sharon Final Year MSC (N) Obstetrics and Gynaecology Nursingkalla sharonNo ratings yet

- Antepartum Haemorrhage: Women's & Children's ServicesDocument4 pagesAntepartum Haemorrhage: Women's & Children's ServicesYwagar YwagarNo ratings yet

- Excess Amniotic Fluid Causes and DiagnosisDocument2 pagesExcess Amniotic Fluid Causes and DiagnosisAde Yonata100% (1)

- Abruptio PlacentaDocument3 pagesAbruptio Placentachichilovesyou100% (1)

- Assesment and Monitoring During 2nd Stage of LabourDocument11 pagesAssesment and Monitoring During 2nd Stage of LabourPragati BholeNo ratings yet

- Adebayo M.O. Care Study On Ovarian CystectomyDocument47 pagesAdebayo M.O. Care Study On Ovarian CystectomyDamilola Olowolabi AdebayoNo ratings yet

- PP Insect Bite 2007 (Print)Document16 pagesPP Insect Bite 2007 (Print)Ali RumiNo ratings yet

- Ectopic Pregnancy: DR .Urmila KarkiDocument27 pagesEctopic Pregnancy: DR .Urmila KarkiBasudev chNo ratings yet

- CPD, Dystocia, Fetal Distress OutputDocument8 pagesCPD, Dystocia, Fetal Distress OutputJohn Dave AbranNo ratings yet

- Tracheo-Oesophageal FistulaDocument19 pagesTracheo-Oesophageal Fistularajan kumar100% (3)

- Infantile Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis (IHPS) : IncidenceDocument9 pagesInfantile Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis (IHPS) : IncidenceRaed AlhnaityNo ratings yet

- Drugs Used to Manage Pre-EclampsiaDocument11 pagesDrugs Used to Manage Pre-EclampsiaVenance NtengoNo ratings yet

- Engorgement PDFDocument1 pageEngorgement PDFrevathidadam55555No ratings yet

- How To Read A CTGDocument11 pagesHow To Read A CTGiwennieNo ratings yet

- The Pathophysiology of PPROMDocument2 pagesThe Pathophysiology of PPROMNano KaNo ratings yet

- Hydatidiform MoleDocument27 pagesHydatidiform MolemanjuNo ratings yet

- SIM - Anemias of PregnancyDocument17 pagesSIM - Anemias of PregnancyGabrielle EvangelistaNo ratings yet

- Case Study of Cesarean SectionDocument9 pagesCase Study of Cesarean SectionErika Joy Imperio0% (1)

- Case PresentationDocument36 pagesCase PresentationSaba TariqNo ratings yet

- Endometriosis PresentationDocument58 pagesEndometriosis PresentationBRI KUNo ratings yet

- Uterine ProlapseDocument11 pagesUterine ProlapseMelDred Cajes BolandoNo ratings yet

- Gastric Outlet Obstruction, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandGastric Outlet Obstruction, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNo ratings yet

- JADWAL Jaga Isip 2016-2017Document25 pagesJADWAL Jaga Isip 2016-2017Baharudin Yusuf RamadhaniNo ratings yet

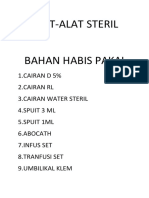

- Alat AlatDocument5 pagesAlat AlatBaharudin Yusuf RamadhaniNo ratings yet

- 3919Document8 pages3919Baharudin Yusuf RamadhaniNo ratings yet

- Persamaan Persepsi Skenario Iii Repro I PDFDocument5 pagesPersamaan Persepsi Skenario Iii Repro I PDFBaharudin Yusuf RamadhaniNo ratings yet

- Renal Stone Disease Diagnosis and TreatmentDocument13 pagesRenal Stone Disease Diagnosis and TreatmentBaharudin Yusuf RamadhaniNo ratings yet

- House Brackmann: Bels Palsy ScoreDocument2 pagesHouse Brackmann: Bels Palsy ScoreBaharudin Yusuf RamadhaniNo ratings yet

- UrolitiasisDocument98 pagesUrolitiasissstdocNo ratings yet

- Ophthalmologic Concerns With Alternative Medicinal TherapiesDocument26 pagesOphthalmologic Concerns With Alternative Medicinal TherapiesBaharudin Yusuf Ramadhani100% (1)

- Anxiety and Depression in Caregivers of Chronic Mental Illness 2167 1044 1000254Document2 pagesAnxiety and Depression in Caregivers of Chronic Mental Illness 2167 1044 1000254Baharudin Yusuf RamadhaniNo ratings yet

- Abn Abn0000119Document10 pagesAbn Abn0000119Baharudin Yusuf RamadhaniNo ratings yet

- Pelvic Anatomy ReviewDocument33 pagesPelvic Anatomy ReviewBaharudin Yusuf RamadhaniNo ratings yet

- Urinalisis Unisma 2013Document48 pagesUrinalisis Unisma 2013Baharudin Yusuf RamadhaniNo ratings yet

- Daftar PustakaDocument1 pageDaftar PustakaBaharudin Yusuf RamadhaniNo ratings yet

- Consepsi, Nidasi, Plasentasi Dan Pertembuhan FetusDocument49 pagesConsepsi, Nidasi, Plasentasi Dan Pertembuhan FetusBaharudin Yusuf RamadhaniNo ratings yet

- Surgical Management of Cervical Myelopathy: Clinical EvaulationDocument10 pagesSurgical Management of Cervical Myelopathy: Clinical EvaulationBaharudin Yusuf RamadhaniNo ratings yet

- ADocument11 pagesABaharudin Yusuf RamadhaniNo ratings yet

- ReadmedasfDocument4 pagesReadmedasfBaharudin Yusuf RamadhaniNo ratings yet

- Follow UpDocument3 pagesFollow UpBaharudin Yusuf RamadhaniNo ratings yet

- HGJHDocument7 pagesHGJHBaharudin Yusuf RamadhaniNo ratings yet

- Surgical Management of Cervical Myelopathy: Clinical EvaulationDocument10 pagesSurgical Management of Cervical Myelopathy: Clinical EvaulationBaharudin Yusuf RamadhaniNo ratings yet

- Da - Cervical Laminoplasty Review Adv Ortho 2012Document5 pagesDa - Cervical Laminoplasty Review Adv Ortho 2012Baharudin Yusuf RamadhaniNo ratings yet

- Harvard Referencing GuideDocument49 pagesHarvard Referencing GuideKwadwo OwusuNo ratings yet

- 1752 1947 6 171Document6 pages1752 1947 6 171Baharudin Yusuf RamadhaniNo ratings yet

- Sign 95Document59 pagesSign 95Baharudin Yusuf RamadhaniNo ratings yet

- Cover ApikDocument13 pagesCover ApikBaharudin Yusuf RamadhaniNo ratings yet

- Multilevel Cervical Myelopathy Treatment Opendoor Laminoplasty Vs Multiple Cervical Arcocristectomies RNBLDocument5 pagesMultilevel Cervical Myelopathy Treatment Opendoor Laminoplasty Vs Multiple Cervical Arcocristectomies RNBLBaharudin Yusuf RamadhaniNo ratings yet

- Abbott 26090 CAG Brochure r2 ZincDocument24 pagesAbbott 26090 CAG Brochure r2 ZinctheresmariajNo ratings yet

- اسئله جراحه مدققه تDocument3 pagesاسئله جراحه مدققه تEba'a GamilNo ratings yet

- Hospital ListDocument10 pagesHospital ListHercules SafesNo ratings yet

- Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR)Document17 pagesCardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR)Tin Maw100% (2)

- Annual Stock Taking Board For The Year of 2010 - 2011 List of Maj Med Eqpt-Held by Echs Polyclinic (Type-D) NagapattinamDocument17 pagesAnnual Stock Taking Board For The Year of 2010 - 2011 List of Maj Med Eqpt-Held by Echs Polyclinic (Type-D) NagapattinamechsngtNo ratings yet

- Death CertificateDocument3 pagesDeath CertificateRehman MarufNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S002239131360030X MainDocument6 pages1 s2.0 S002239131360030X MainAmar Bhochhibhoya100% (1)

- Diagnosis and Treatment of Perianal Crohn Disease .27Document12 pagesDiagnosis and Treatment of Perianal Crohn Disease .27Zafitri AsrulNo ratings yet

- Superior Laryngeal Nerve InjuryDocument11 pagesSuperior Laryngeal Nerve InjuryBrilli Bagus DipoNo ratings yet

- Zimmer Nexgen Tibial Stem Extension Augmentation Surgical TechniqueDocument16 pagesZimmer Nexgen Tibial Stem Extension Augmentation Surgical TechniqueTudor MadalinaNo ratings yet

- EntropionDocument1 pageEntropionLouis EkaputraNo ratings yet

- Trust Board: Board of Direction:: 9 No. 2 April - June 2015 Published Every 3 Month ISSN 1978 - 3744Document12 pagesTrust Board: Board of Direction:: 9 No. 2 April - June 2015 Published Every 3 Month ISSN 1978 - 3744febrian rahmatNo ratings yet

- Resident and Fellow Page: Book ReviewDocument1 pageResident and Fellow Page: Book ReviewSagita NindraNo ratings yet

- Glaucoma: Prepared by If You Have Any Question or Find Any Mistake, Contact MeDocument8 pagesGlaucoma: Prepared by If You Have Any Question or Find Any Mistake, Contact MeFatimah AlsultanNo ratings yet

- Causes & Management of Open ApicesDocument2 pagesCauses & Management of Open ApiceskowmudimaddineniNo ratings yet

- Video Telescopic Operating Microscope - A Recent Development in Reptile MicrosurgeryDocument4 pagesVideo Telescopic Operating Microscope - A Recent Development in Reptile MicrosurgeryChecko LatteNo ratings yet

- Mechanical Versus Bioprosthetic Aortic Valve ReplacementDocument13 pagesMechanical Versus Bioprosthetic Aortic Valve ReplacementAndrea OrtizNo ratings yet

- Clark2016 Benign Anal DiseaseDocument7 pagesClark2016 Benign Anal DiseaseJohana Dellaneira Aucancela RamosNo ratings yet

- Clean Intermittent Catheterization GuideDocument2 pagesClean Intermittent Catheterization GuideAndi Sri Wulan PurnamaNo ratings yet

- Atlas of Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery (Histerectomia)Document34 pagesAtlas of Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery (Histerectomia)Jose Augusto Antonio Alves Flor0% (1)

- WKoTaXFrZtNGz2xzB - Seeleys Ch1Document43 pagesWKoTaXFrZtNGz2xzB - Seeleys Ch1Björn Þór SigurbjörnssonNo ratings yet

- Distal Biceps Repair Rehabilitation Protocol by Tendayi MutsopotsiDocument5 pagesDistal Biceps Repair Rehabilitation Protocol by Tendayi MutsopotsiPhysiotherapy Care SpecialistsNo ratings yet

- Informed Consent For Bone Grafting SurgeryDocument1 pageInformed Consent For Bone Grafting SurgeryJ&A Partners JANNo ratings yet

- Kls Martin Instrumenter Til HaandkirurgiDocument32 pagesKls Martin Instrumenter Til HaandkirurgiAmeer KhanNo ratings yet