Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Projective Technique

Uploaded by

Abhilash PonnamCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Projective Technique

Uploaded by

Abhilash PonnamCopyright:

Available Formats

Projective Techniques in Marketing Research Author(s): Mason Haire Source: The Journal of Marketing, Vol. 14, No. 5 (Apr.

, 1950), pp. 649-656 Published by: American Marketing Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1246942 Accessed: 29/07/2010 05:05

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=ama. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

American Marketing Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Marketing.

http://www.jstor.org

TIHE

al

Volume XIV

APRIL, 1950

Number 5

TECHNIQUESIN MARKETING PROJECTIVE RESEARCH

MASON HAIRE University of California, Berkeley a well accepted maxim in merchan- what kindof peopledrankeachkind, and

IT

IS

dizing that, in many areas, we are selling the sizzle rather than the steak. Our market research techniques, however, in many of these same areas, are directed toward the steak. The sizzle is the subjectivereactionof the consumer; the steak the objectivecharacteristics of the product. The consumer'sbehavior will be based on the formerrather than the latter set of characteristics. How can we come to know them better? When we approach a consumer directly with questions about his reaction to a productwe often get false and misleading answers to our questions. Very often this is becausethe question which we heard ourselvesask was not the one (ornot the only one) that the respondent heard.For example:A brewery madetwo kinds of beer. To guide their merchandizing techniquesthey wanted to know

there were particularly,what differences between the two groups of consumers. A survey was conductedwhichled up to the questions"Do you drink beer?" (If yes) "Do you drink the Light or Regular?"(These were the two trade names under which the company marketed.) After identifying the consumers of each product it was possible to find out about the characteristicsof each groupso that appropriateappealscould be used, media chosen,etc. An interesting anomaly appeared in the survey data, however. The interviewing showed (on a reliable sample) that consumers drankLightover Regular in the ratio of 3 to i. The companyhad been producingand selling Regularover Light for some time in a ratio of 9 to I. Clearly, the attempt to identify characteristics of the two kinds was a failure.

649

650

650THEJORNA

THE JOURNAL O OF MREIN MARKETING

What madethem miss so far? representthe truth, but the respondent When we say "Do you drink Lightor will feel like a fool and the interviewer Regular?"we are at once asking which will not go away. Much better produce brand is used, but also, to some extent, a clicheand be rid of him. saying "Do you drinkthe regularrun-ofTHE NATURE OF PROJECTIVE TESTS the-millproductor do you drinkthe one that is morerefinedand showsmoredisStill other kinds of motives exist of criminationand taste?" The preponder- which the respondent may not be exance of "Light"undoubtedlyflows from plicitly conscious himself. The product this kind of distortion. may be seen by him as related to things When we ask questions of this sort or peopleor valuesin his life, or as having about the product we are very often a certain role in the scheme of things, asking also about the respondent.Not and yet he may be quite unable, in reonly do we say "What is sponse to a direct question, to describe productlike?"but, indirectly"Whatare these aspectsof the object. Nevertheless, you like?"Ourresponsesare often made these characteristicsmay be of great up of both elements inextricablyinter- importanceas motives. How can we get woven. The answersto the second ques- at them? tion will carry cliches and stereotypes, Clinical psychologistshave long been anddistortions, when- faced with a parallelset of problems.It blocks,inhibitions, ever we approach an areathat challenges is quite usual for a patient to be unable the person'sidea of himself. or unwillingto tell the therapistdirectly There are many things that we need what kinds of things are stirring in his to know about a consumer'sreactionto motivationalpattern.Informationabout a productthat he can not tell us because these drives are of vital importanceto they are to some extent socially unac- the processof cure, so a good deal of receptable. For instance, the snob appeal searchhas been directedtowardsthe deof a product vitally influencesits sale, velopmentof techniquesto identify and but it is a thing that the consumerwill define them. The development of pronot like to discuss explicitly. In other jective techniquesas diagnostictools has cases the consumeris influencedby mo- provided one of the most useful means tives of which he is, perhaps, vaguely to uncover such motivations, and the aware,but whichhe findsdifficultto put market-researcher can well affordto borinto words. The interviewer-respondent row their essentials from the therapist. relationshipputs a good deal of pressure Basically, a projective test involves on him to reply and to make sense in presentingthe subject with an ambiguhis reply. Consequently, he gives us ous stimulus-one that does not quite stereotypicalresponsesthat use cliches make sense in itself-and asking him which are commonlyacceptablebut do to makesense of it. The theory is that in not necessarily represent the true mo- orderto make it makesense he will have tives. Many of our motives do not, in to add to it-to fill out the picture-and fact, "make sense," and are not logical. in so doing he projects part of himself The question-answerrelation demands into it. Since we know what was in the sense above all. If the responsedoes not original stimulus we can quite easily representthe truestate of affairsthe in- identify the parts that were added, and, terviewerwill never know it. He will go in this way, painlessly obtain informaaway. If it does not make sense it may tion aboutthe person.

THE JOURNAL OF MARKETING

651

Examples of these tests come readily to hand. Nearly everyone is familiar with the Rorschach Test, in whicha subis shown a series of ink-blots and ject asked to tell what they look like. Here the stimulus is incompletein itself, and the interpretationsupplied by the patient provides useful information.This test yields fairly general answersabout the personality, however, and often we would like to narrowdown the area in which the patient is supplyinginformation. The Thematic ApperceptionTest offers a good exampleof this function.Let us suppose that with a particular patient we have reasonto supposethat his relationto figuresof authorityis crucial to his therapeuticproblem.We can give him a seriesof pictureswherepeople are shown, but where the relationship of authority or the characteristicsof the authoritarianfigure are not complete. He is asked to tell a story about each picture. If in each story the subordinate finally kills the figure of authority we have certain kinds of knowledge;if, on the other hand, he always builds the story so the subordinatefigure achieves a secure and comfortable dependence, we have quite differentinformation. It is often quite impossibleto get the subject to tell us these things directly. Either he cannot or will not do so. Indirectly, however, he will tell us how he sees authority. Can we get him, similarly,to tell us how a productlooks to him in his private view of the world?

APPLICATIONOF PROJECTIVETEST IN MARKETRESEARCH

use instant coffee?" (If No) "What do you dislike about it?" The bulk of the unfavorableresponsesfell into the general area "I don't like the flavor."This is such an easy answerto a complexquestion that one may suspect it is a stereotype, which at once gives a sensible response to get rid of the interviewerand concealsother motives. How can we get behindthis facade? In this case an indirect approachwas used. Two shoppinglists were prepared. They were identical in all respects, except that one list specifiedNescafe and one Maxwell House Coffee. They were administeredto alternatesubjects, with no subject knowing of the existence of the other list. The instructions were "Read the shopping list below. Try to projectyourselfinto the situation as far as possible until you can more or less characterize the womanwho bought the Then write a brief description groceries. of her personalityand character.Wherever possible indicate what factors influencedyourjudgement."

List I Shopping

Poundanda halfof hamburger 2 loavesWonder bread bunch of carrots I canRumford's Powder Baking Nescaf6 instantcoffee 2 cansDel Montepeaches 5 Ibs.potatoes

List II Shopping

Let us look at an exampleof this kind of thing in market research. For the purposes of experiment a conventional survey was made of attitudes toward Nescafe, an instant coffee.The questionnaire included the questions "Do you

Poundanda halfof hamburger 2 loavesWonder bread bunch of carrots i canRumford's Powder Baking I lb. Maxwell HouseCoffee (DripGround) 2 cansDel Montepeaches 5 lbs. potatoes Fifty people respondedto each of the two shoppinglists given above. The responses to these shoppinglists provided some very interestingmaterial.The fol-

652

THE yOURNAL OF MARKET1NG

On the other hand, coffee has a pecuof their delowing main characteristics liar role in relationto the householdand can be given: scriptions the character.We may home-and-family I. 48 per cent of the peopledescribedthe woman who bought Nescafe as lazy; well have a picture,in the shadowypast, 4 per cent describedthe woman who of a big black range that is always hot with baking and cooking,and has a big bought MaxwellHouse as lazy. 2. 48 per cent of the peopledescribed the enamelledpot of coffee warmingat the woman who bought Nescaf6 as failing back. When a neighbordrops in during to plan householdpurchases andsched- the a cup of coffeeis a medium ules well; I2 per cent described the of morning, that does somewhat the hospitality woman who bought Maxwell House same as cocktails in the late afterthing this way. but does it in a broader noon, sphere. the Nescaf6woman 3. 4 per cent described These are real and important as thrifty; I6 per cent described the aspects of coffee. They are not physical characMaxwellHouse woman as thrifty. teristicsof the product,but they are real 12 per cent describedthe Nescaf6 woman as spendthrift; o percent described values in the consumer'slife, and they the MaxwellHouse womanthis way. influence his purchasing. We need to 4. I6 per cent described the Nescaf6 know and assess them. The "labor-savwoman as not a good wife; o per cent ing" aspect of instant coffee, far from describedthe Maxwell House woman being an asset, may be a liability in that this way. it violates these traditions. How often the Nescafewoman 4 percent described as a good wife; i6 per cent described have we heard a wife respondto "This the Maxwell House woman as a good cake is delicious!"with a pretty blush and "Thank you-I made it with such wife. and such a prepared cake mix." This A clear picture begins to form here. responseis so invariableas to seem alInstant coffee represents a departure most compulsive.It is almost unthinkfrom "home-made"coffee, and the tra- able to anticipate a reply "Thank you, ditions with respect to caring for one's I made it with Pillsbury'sflour,Fleischfamily. Coffee-making is taken seriously, man's yeast, and Borden'smilk." Here with vigorous proponents for laborious the specificationsare unnecessary. All drip and filter-paper methods, firm be- that is relevant is the implied "I made lievers in coffee boiled in a battered it"-the art and the credit are carried sauce pan, and the like. Coffee drinking directlyby the verb that coversthe procis a form of intimacy and relaxation that ess of mixing and processingthe ingregives it a special character. dients. In ready-mixed foodsthereseems On the one hand, coffee making is an to be a drive to refusecredit compulsive art. It is quite common to hear a woman for the product,becausethe accomplishsay, "I can't seem to make good coffee," ment is not the housewife's but the in the same way that one might say, "I company's. can't learn to play the violin." It is acIn this experiment, as a penalty for ceptable to confess this inadequacy, for using "synthetics" the woman who making coffee well is a mysterious touch buys Nescaf6 pays the price of being that belongs, in a shadowy tradition, to seen as a poor wife, lazy, spendthrift, the plump, aproned figure who is a little and as to plan well for her family. lost outside her kitchen but who has a The failing who rejected instant coffee people sure sense in it and among its tools. in the original direct question blamed

THE JOURNAL OF MARKETING I

ITP

653 p Descriptions of a womanwhobought, other among things,Nescafe Instant Coffee "This woman appearsto be either single or living alone. I would guess that she had an officejob. Apparently,she likes to sleep late in the morning,basing my assumption on what she bought such as Instant Coffee whichcan be made in a hurry.She probably also has can [sic]peachesfor breakfast,cans beingeasy to open.Assumingthat she is just average, as opposed to those dazzling natural beauties who do not need much time to make up, she must appearrathersloppy, takinglittle time to makeup in the morning. She is also used to eating supper out, too. Perhaps alone rather than with an escort. An old maid probably." "She seems to be lazy, because of her purchases of canned peaches and instant coffee. She doesn't seem to think, because she bought two loaves of bread, and then baking powder, unless she's thinking of making cake. She probablyjust got married." "I think the womanis the type who never thinks aheadvery far-the type who always sends Junior to the store to buy one item at a time. Also she is fundamentallylazy. All the items, with possibleexceptionof the Rumford's,are easily prepareditems. The girl may be an office girl who is just living from one day to the next in a sort of haphazard sort of life."

its flavor. We may well wonder if their dislike of instant coffee was not to a largeextent occasionedby a fearof being seen by one's self and others in the role they projectedonto the Nescafe woman in the description.When asked directly, however, it is difficult to respondwith this. One can not say, "I don't use Nescaf6 becausepeople will think I am lazy and not a good wife." Yet we know from these data that the feeling regarding laziness and shiftlessness was there. Later studies (reported below) showed that it determined buying habits, and that something could be done about it.

Analysis of Responses

Someexamplesof the type of response received will show the kind of material obtained and how it may be analyzed. Three examplesof each group are given below.

Descriptions of a womanwhobought, other among things,Maxwell HouseCoffee

housewife."

"I'dsayshewasa practical, woman. frugal She boughttoo many potatoes.She must liketo cookandbakeas sheincluded baking She mustnot caremuchabouther powder. as shedoesnot discriminate figure aboutthe foodshe buys." As we read these complete responses "Thewomanis quite influenced by adas we the vertising signified begin to get a feeling for thepicture by specificname on hershopping brands list. Sheprobably is that is created by Nescafe. It is particuquite set in her ways and acceptsno sub- larly interesting to notice that the Nesstitutes." cafe woman is protected, to some extent, "I havebeenableto observe several hun- from the opprobrium of being lazy and dredwomenshoppers who havemadevery seen as a single haphazard by being similar to that listed above,and purchases theonlycluethatI candetectthatmayhave "office girl"-a role that relieves one somebearing on her personality is the Del from guilt for not being interested in Montepeaches. This item whenpurchased the home and food preparation. The references to peaches are signifiwiththeothermore singlyalong staplefoods indicates that she may be anxious to please cant. In one case (Maxwell House) they eitherherself or members of herfamilywith are singled out as a sign that the woman a 'treat.' Sheis probably a thrifty,sensible is thoughtfully preparing a "treat" for

her family. On the other hand, when the

654

THE JOURNAL OF MMARKETING

Nescafe womanbuys them it is evidence that she is lazy, since their "canned" characteris seen as central. In termsof the sortof resultspresented above, it may be useful to demonstrate the way these stories are coded. The following items are extracted from the six storiesquoted: Maxwell House Nescafe

I. practical I. single

frugal likesto cook

set in her ways

office girl sloppy old maid

2. influenced by advertising 2. lazy

3. interestedin family thrifty sensible

does not plan newlywed 3. lazy does not plan officegirl

Items such as these are culled fromeach of the stories. Little by little categories are shaped by the content of the stories furnishesthe dimensionsof analysis as well as the scale values on these dimensions. Second Test It is possible to wonder whether it is true that the opprobrium that is heaped on the Nescaf6 woman comes from her use of a device that represents a shortcut and labor-saver in an area where she is expected to embrace painstaking time-consuming work in a ritualistic

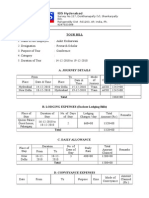

TABLE I. PERSONALITY

themselves. In this way the respondent

way. To test this a variation was introducedinto the shoppinglists. In a second experimentone hundredand fifty housewives were tested with the form given above, but a sample was added t6 this group which respondedto a slightly different form. If we assume that the rejection in the firstexperimentcame from the presenceof a feelingabout synthetic shortcutswe might assumealso that the addition of one more shortcut to both lists would bring the Maxwell House woman more into line with the Nescaf6 wouldnow have woman,since the former the same guilt that the Nescafe woman originallyhad, whilethe Nescafewoman, alreadyconvictedof evading her duties, would be little furtherinjured. In order to accomplishthis a second preparedfood was added to both lists. Immediately after the coffee in both lists the fictitious item, "BlueberryFill Pie Mix" was added. The results are shownin the accompanying table. It will be seen immediately,in the first two columns,that the groupto whomthe originalformof the list weregivenshowed the same kind of differenceas reported above in their estimates of the two women. The group with an additionalprepared food, however, broughtthe Maxwell Coffee woman down until she is virtually undistinguishable from the Nescafe. There seems to be little doubt but that the prepared-food-character,

FOODS

CHARACTERISTICS ASCRIBED TO USERS OF PREPARED

If They Use They are seen as: Not Economical Lazy Poor Personality and Appearance

N=

No Prepared Food (Maxwell House alone) Number

12

Nescafe (alone)

Maxwell House (plus Pie Mix)

Nescafe (plus Pie Mix) PerCent 35 40 40

8 28

72

Per Cent Number 17 24 II 46 39 39

74

Per Cent Number 6 32 62 5 53 7

20

Per Cent Number 30 7 8 25 35 8

20

THE JOURNAL /OURNAL OF OP MARKETING

655 655

and the stigma of avoiding housewifely buy instant coffeeherself.The projected duties is responsible for the projected unacceptable characteristics go with failureto buy, and it does not seem unpersonalitycharacteristics. to assumethat the association warranted Relationto Purchasing is causal. It is still relevant to ask whether the Furthermore, these projected traits existence of these feelingsin a potential are, to some extent, additive. For inconsumeris related to purchasing.It is stance, if a respondent describes the hypothesizedthat these personalityde- woman as having one bad trait only, scriptions provide an opportunity for she is about twice as likely not to have the consumerto project hopes and fears instant coffee. However, if she sees her and anxieties that are relevant to the as having two bad traits, and no good way the product is seen, and that they ones (e.g., lazy, can not cook), she is representimportantparts of her motiva- about three times as likely not to have tion in buyingor not buying.To test this instant coffeeas she is to have it. On the hypothesis, a small sample of fifty otherhand,if she sees her as having two in every way to good traits (e.g., economical, cares for housewives,comparable the groupjust referredto, was given the family), she is aboutsix times as likely to original form of the shoppinglist (Nes- have it as not. cafe only). In addition to obtaining the It was pointed out earlier that some women felt it necessaryto "excuse"the the interviewer, personalitydescription, on a pretext,obtainedpermissionto look womanwho bought Nescaf6 by suggestat her pantry shelves and determine ing that she lived alone and hence could personally whether or not she had in- not be expected to be interested in stant coffeeof any brand.The resultsof cooking, or that she had a job and did this investigation are shown in the ac- not have time to shop better. Women who had instant coffee in the house companyingtable.

LE

II By Women Who Had Instant Coffeein the House (N=32) Number

22

The woman who buys Nescaf6 is seen as:

By Women Who Did Not Have Instant Coffee in the House (N= 8) Number 5

2 o1 2

0

Economical** Not economical Can not cook or does not like to** Plans balanced meals* Good housewife, plans well, cares about family** Poor housewife, does not plan well, does not care about family* Lazy* *A

o 5 9 9 5 6

Per Cent 70 o 6

29 29

Per Cent 28

II

55

II 0

6 19

7 7

39 39

single asterisk indicates that differences this great would be observed only 5 times out of Ioo in repeated samplings of a population whose true difference is zero. ** A double asterisk indicates that the chances are I in Ioo. We are justified in rejecting the hypothesis that there is no difference between the groups.

The trend of these data shows conclusively that if a respondent sees the woman who buys Nescaf6 as having undesirable traits, she is not likely to

found excuses almost twice as often as those who did not use instant coffee (12 out of 32, or 42 per cent, against 4 out of i8, or 22 per cent). These "excuses" are

656 656

THE OF MARKETING MARKETING THE yOURNAL JOURNAL OF

The vitally importantformerchandizing. need for an excuse shows there is a barrier to buying in the consumer'smind. The presenceof excusesshowsthat there is a way aroundthe barrier. The content of the excuses themselves provides valuable clues for directing appeals toward reducingbuying resistance.

CONCLUSIONS

There seems to be no questionthat in the experimental situation described here: (I) Motives exist which are below the levelof verbalization because theyare difficult to versocially unacceptable, balizecogently, or unrecognized. related (2) Thesemotivesare intimately to the decision to purchase or not to and purchase, (3) It is possibleto identifyand assess such motives by approaching them indirectly. Two important general points come out of the work reported.The first is in the statement of the problem. It is necessaryforus to see a productin terms of a set of characteristics and attributes whicharepartof the consumer's "private world,"and as such may have no simple relationship to characteristics of the object in the "real"world. Each of us lives in a world which is composed of more than physical things and people. It is made up of goals, paths to goals, barriers,threats, and the like, and an

individual's behavior is oriented with as much respect to these characteristics as to the "objective"ones. In the area of merchandizing, a product'scharacter of beingseen as a path to a goal is usually very muchmoreimportantas a determinant of purchasingthan its physical dimensions. We have taken advantageof these qualities in advertisingand merfora long time by an intuitive chandizing sort of "playing-by-ear" on the subjective aspects of products.It is time for a systematic attack on the problemof the phenomenological descriptionof objects. What kinds of dimensionsare relevant to this worldof goals and paths and barriers? What kind of terms will fit the phenomenologicalcharacteristicsof an object in the same sense that the centimetre-gram-second system fits its physical dimensions?We need to know the answersto such questions,and the psychologicaldefinitionsof valued objects. The second general point is the methodologicalone that it is possible, by using appropriate techniques,to find out from the respondentwhat the pheof various nomenologicalcharacteristics objects may be. By and large, a direct approach to this problem in terms of straightforward questions will not yield answers. It is possible,howsatisfactory ever, by the use of indirect techniques, to get the consumer to provide, quite unselfconsciously,a description of the value-character of objectsin his environment.

You might also like

- It Declaration Form For 2016-17Document4 pagesIt Declaration Form For 2016-17Abhilash PonnamNo ratings yet

- IBS Hyderabad: Survey No.157, Donthanapally (V), Shankarpally (M), Rangareddy Dist - 501203, AP, India, Ph. 9247021088Document3 pagesIBS Hyderabad: Survey No.157, Donthanapally (V), Shankarpally (M), Rangareddy Dist - 501203, AP, India, Ph. 9247021088Abhilash PonnamNo ratings yet

- Shri Shiva RahasyaDocument223 pagesShri Shiva RahasyaSivason75% (4)

- Subject: Requisition To Change The Authorization Signatures in Respect of TheDocument2 pagesSubject: Requisition To Change The Authorization Signatures in Respect of TheAbhilash Ponnam100% (1)

- REFRENCESDocument11 pagesREFRENCESAbhilash PonnamNo ratings yet

- Measuring Quality in Qualitative ResearchDocument13 pagesMeasuring Quality in Qualitative ResearchAbhilash PonnamNo ratings yet

- PREFMAPS MCA TS ANALYSIS - PPSXDocument24 pagesPREFMAPS MCA TS ANALYSIS - PPSXAbhilash PonnamNo ratings yet

- Shri Shiva RahasyaDocument223 pagesShri Shiva RahasyaSivason75% (4)

- SBM 1Document343 pagesSBM 1Abhilash Ponnam100% (1)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- CLC Customer Info Update Form v3Document1 pageCLC Customer Info Update Form v3John Philip Repol LoberianoNo ratings yet

- M Series CylindersDocument61 pagesM Series CylindersAndres SantanaNo ratings yet

- A Research About The Canteen SatisfactioDocument50 pagesA Research About The Canteen SatisfactioJakeny Pearl Sibugan VaronaNo ratings yet

- Nexus Undercarriage Cross Reference GuideDocument185 pagesNexus Undercarriage Cross Reference GuideRomanNo ratings yet

- Article 4Document31 pagesArticle 4Abdul OGNo ratings yet

- (NTA) SalaryDocument16 pages(NTA) SalaryHakim AndishmandNo ratings yet

- Uniform Bonding Code (Part 2)Document18 pagesUniform Bonding Code (Part 2)Paschal James BloiseNo ratings yet

- Embedded Systems: Martin Schoeberl Mschoebe@mail - Tuwien.ac - atDocument27 pagesEmbedded Systems: Martin Schoeberl Mschoebe@mail - Tuwien.ac - atDhirenKumarGoleyNo ratings yet

- Research Grants Final/Terminal/Exit Progress Report: Instructions and Reporting FormDocument13 pagesResearch Grants Final/Terminal/Exit Progress Report: Instructions and Reporting FormBikaZee100% (1)

- BC Specialty Foods DirectoryDocument249 pagesBC Specialty Foods Directoryjcl_da_costa6894No ratings yet

- Liability WaiverDocument1 pageLiability WaiverTop Flight FitnessNo ratings yet

- Frequency Meter by C Programming of AVR MicrocontrDocument3 pagesFrequency Meter by C Programming of AVR MicrocontrRajesh DhavaleNo ratings yet

- Javascript: What You Should Already KnowDocument6 pagesJavascript: What You Should Already KnowKannan ParthasarathiNo ratings yet

- Activate Adobe Photoshop CS5 Free Using Serial KeyDocument3 pagesActivate Adobe Photoshop CS5 Free Using Serial KeyLukmanto68% (28)

- LeasingDocument2 pagesLeasingfollow_da_great100% (2)

- VBScriptDocument120 pagesVBScriptdhanaji jondhaleNo ratings yet

- BCM Risk Management and Compliance Training in JakartaDocument2 pagesBCM Risk Management and Compliance Training in Jakartaindra gNo ratings yet

- Continuous torque monitoring improves predictive maintenanceDocument13 pagesContinuous torque monitoring improves predictive maintenancemlouredocasadoNo ratings yet

- Draft of The English Literature ProjectDocument9 pagesDraft of The English Literature ProjectHarshika Verma100% (1)

- Sample Contract Rates MerchantDocument2 pagesSample Contract Rates MerchantAlan BimantaraNo ratings yet

- Evan Gray ResumeDocument2 pagesEvan Gray Resumeapi-298878624No ratings yet

- Unit 13 AminesDocument3 pagesUnit 13 AminesArinath DeepaNo ratings yet

- Acceptance and Presentment For AcceptanceDocument27 pagesAcceptance and Presentment For AcceptanceAndrei ArkovNo ratings yet

- De Thi Thu THPT Quoc Gia Mon Tieng Anh Truong THPT Hai An Hai Phong Nam 2015Document10 pagesDe Thi Thu THPT Quoc Gia Mon Tieng Anh Truong THPT Hai An Hai Phong Nam 2015nguyen ngaNo ratings yet

- STS Chapter 5Document2 pagesSTS Chapter 5Cristine Laluna92% (38)

- SHIPPING TERMSDocument1 pageSHIPPING TERMSGung Mayura100% (1)

- The Essence of Success - Earl NightingaleDocument2 pagesThe Essence of Success - Earl NightingaleDegrace Ns40% (15)

- Equity AdvisorDocument2 pagesEquity AdvisorHarshit AgarwalNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument3 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Process ValidationDocument116 pagesProcess ValidationsamirneseemNo ratings yet