Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ninal Vs Bayadog DIGEST

Uploaded by

Earleen Del RosarioOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ninal Vs Bayadog DIGEST

Uploaded by

Earleen Del RosarioCopyright:

Available Formats

Ninal vs Bayadog GR 133778 14 March 2000 First Division Justice Ynares-Santiago Facts: May the heirs of a deceased person

file a petition for the declaration of nullity of his marriage after his death? 26 September 1974 - Pepito Ninal married Teodulfa Bellones. 24 April 1985 - Pepito shot Teodulfa and the latter died. 11 December 1986 - Pepito and Norma Bayadog got married without any license, stating in an affidavit that they have lived together as husband and wife for at least five years and were thus exempt from securing a marriage license. 19 February 1997 - Pepito died in a car accident. After their father's death, Petitioners filed a declaration of nullity of the marriage of Pepito to Norma, alleging that the marriage was void for lack of marriage license. The case was filed under the assumption that the validity or invalidity of the second marriage would affect petitioner's successional rights. Norma filed a motion to dismiss on the ground that the petitioners have no cause of action since they are not among the persons who could file an action for "annulment of marriage" under Article 47 of the Family Code. Judge Marcos of the RTC of CEbu dismissed the petition after finding that the Family Code is "rather silent, obscure, insufficient" in resolving the following issues: (1) Whether or not plaintiffs have a cause of action against defendant in asking for the declaration of the nullity of marriage of their deceased father, Pepito G. Nial, with her specially so when at the time of the filing of this instant suit, their father Pepito G. Nial is already dead;

(2) Whether or not the second marriage of plaintiffs' deceased father with defendant is null and void ab initio; (3) Whether or not plaintiffs are estopped from assailing the validity of the second marriage after it was dissolved due to their father's death. Held: The Court held that the Old Civil Code is the applicable law to determine the validity of the two marriages as they both had been solemnized before the Family Code took effect. Accordingly, the Old Civil Code provided exceptions for the requirement of marriage licences, one of which is that provided in Article 76, 14 referring to the marriage of a man and a woman who have lived together and exclusively with each other as husband and wife for a continuous and unbroken period of at least five years before the marriage. The rationale why no license is required in such case is to avoid exposing the parties to humiliation, shame and embarrassment concomitant with the scandalous cohabitation of persons outside a valid marriage due to the publication of every applicant's name for a marriage license. The publicity attending the marriage license may discourage such persons from legitimizing their status. 15 To preserve peace in the family, avoid the peeping and suspicious eye of public exposure and contain the source of gossip arising from the publication of their names, the law deemed it wise to preserve their privacy and exempt them from that requirement. The Court ruled that the marriage of Pepito with Norma was void ab initio because they did not live as husband and wife for five years because when they started living together, Pepito's marriage to his first wife was still subsisting. The The Court said that "the five-year common-law cohabitation period, which is counted back from the date of celebration of marriage, should be a period of legal union had it not been for the absence of the marriage." This 5-year period should be the years immediately before the day of the marriage and it should be a period of cohabitation characterized by exclusivity meaning no third party was involved at any time

within the 5 years and continuity that is unbroken. Otherwise, if that continuous 5-year cohabitation is computed without any distinction as to whether the parties were capacitated to marry each other during the entire five years, then the law would be sanctioning immorality and encouraging parties to have common law relationships and placing them on the same footing with those who lived faithfully with their spouse. In this case, at the time of Pepito and respondent's marriage, it cannot be said that they have lived with each other as husband and wife for at least five years prior to their wedding day. From the time Pepito's first marriage was dissolved to the time of his marriage with respondent, only about twenty months had elapsed. Even assuming that Pepito and his first wife had separated in fact, and thereafter both Pepito and respondent had started living with each other that has already lasted for five years, the fact remains that their five-year period cohabitation was not the cohabitation contemplated by law. It should be in the nature of a perfect union that is valid under the law but rendered imperfect only by the absence of the marriage contract. Pepito had a subsisting marriage at the time when he started cohabiting with respondent. It is immaterial that when they lived with each other, Pepito had already been separated in fact from his lawful spouse. The subsistence of the marriage even where there was actual severance of the filial companionship between the spouses cannot make any cohabitation by either spouse with any third party as being one as "husband and wife" As to who can file a petition to declare the nullity of marriage, the Family Code is silent. The Court made a distinction that void and voidable marriages are not identicial. Voidable marriages are those which are valid until otherwise delcared by the court, while marriages that are void ab initio are considered as having never to have taken place and cannot be the source of rights. Voidable marriages can be generally ratified or confirmed by free cohabitation or prescription while the other can never be ratified. A voidable marriage

cannot be assailed collaterally except in a direct proceeding while a void marriage can be attacked collaterally. Consequently, void marriages can be questioned even after the death of either party but voidable marriages can be assailed only during the lifetime of the parties and not after death of either, in which case the parties and their offspring will be left as if the marriage had been perfectly valid. That is why the action or defense for nullity is imprescriptible, unlike voidable marriages where the action prescribes. Only the parties to a voidable marriage can assail it but any proper interested party may attack a void marriage. Void marriages have no legal effects except those declared by law concerning the properties of the alleged spouses, regarding co-ownership or ownership through actual joint contribution and its effect on the children born to such void marriages as provided in Article 50 in relation to Article 43 and 44 as well as Article 51, 53 and 54 of the Family Code. On the contrary, the property regime governing voidable marriages is generally conjugal partnership and the children conceived before its annulment are legitimate. Jurisprudence under the Civil Code states that no judicial decree is necessary in order to establish the nullity of a marriage. "A void marriage does not require a judicial decree to restore the parties to their original rights or to make the marriage void but though no sentence of avoidance be absolutely necessary, yet as well for the sake of good order of society as for the peace of mind of all concerned, it is expedient that the nullity of the marriage should be ascertained and declared by the decree of a court of competent jurisdiction."

You might also like

- Ninal Vs Bayadog DigestedDocument2 pagesNinal Vs Bayadog DigestedTechie Pagunsan100% (3)

- Supreme Court Rules Second Marriage Void Due to Previous Undissolved MarriageDocument8 pagesSupreme Court Rules Second Marriage Void Due to Previous Undissolved MarriageXing Keet LuNo ratings yet

- Carino Vs Carino - DigestDocument3 pagesCarino Vs Carino - DigestEva Trinidad100% (2)

- Ayala Investment V CA DigestDocument3 pagesAyala Investment V CA DigestMark Joseph Pedroso CendanaNo ratings yet

- Republic v. Iyoy, 407 SCRA 508Document3 pagesRepublic v. Iyoy, 407 SCRA 508Janine IsmaelNo ratings yet

- De Castro vs. de Castro DIGESTDocument2 pagesDe Castro vs. de Castro DIGESTJustin Torres100% (3)

- Standard Oil Vs Arenas, VillanuevaDocument3 pagesStandard Oil Vs Arenas, Villanuevamikhailjavier100% (4)

- Dino Vs Dino (Digest)Document2 pagesDino Vs Dino (Digest)Liaa Aquino100% (3)

- Andal Vs MacaraigDocument1 pageAndal Vs MacaraigJomar TenezaNo ratings yet

- Ocampo vs. FlorencianoDocument2 pagesOcampo vs. Florencianoneo paul100% (1)

- SC rules on marriage nullity and property rightsDocument3 pagesSC rules on marriage nullity and property rightsMikaela RoblesNo ratings yet

- Valdes v. RTCDocument2 pagesValdes v. RTChannahnueveNo ratings yet

- Morigo v. PeopleDocument5 pagesMorigo v. PeoplePrinsesaJuuNo ratings yet

- Brown V Yambao, RecriminationDocument2 pagesBrown V Yambao, RecriminationKelsey Olivar MendozaNo ratings yet

- Case Martinez Vs Tan 12 Phil 731Document1 pageCase Martinez Vs Tan 12 Phil 731Jay Kent RoilesNo ratings yet

- Francisco vs. CADocument3 pagesFrancisco vs. CAKaren P. LusticaNo ratings yet

- Capili Vs People (2013)Document1 pageCapili Vs People (2013)Carlota Nicolas VillaromanNo ratings yet

- Jader Manalo V CamaisaDocument2 pagesJader Manalo V CamaisaSoc100% (1)

- Remrev2 Digest - Abbas V AbbasDocument2 pagesRemrev2 Digest - Abbas V AbbasDrizzyNo ratings yet

- Judge's authority to solemnize marriageDocument2 pagesJudge's authority to solemnize marriageArmando Mata100% (2)

- Alonzo v. PaduaDocument2 pagesAlonzo v. PaduaYvette MoralesNo ratings yet

- Unborn Child Death BenefitsDocument3 pagesUnborn Child Death BenefitsPanday L. Mason100% (1)

- Quimiguing Vs IcaoDocument1 pageQuimiguing Vs Icaoshopee onlineNo ratings yet

- Jocson vs. CADocument1 pageJocson vs. CACarlota Nicolas VillaromanNo ratings yet

- Republic v. Albios DigestDocument2 pagesRepublic v. Albios Digestviva_3375% (4)

- Cancellation of Civil Status Entries Under Rule 108 When No Marriage Took PlaceDocument2 pagesCancellation of Civil Status Entries Under Rule 108 When No Marriage Took PlaceRenzErwinGozum50% (2)

- DigestDocument12 pagesDigestCharles AtienzaNo ratings yet

- Prima Partosa Jo v. Court of AppealsDocument2 pagesPrima Partosa Jo v. Court of AppealsIkangApostol100% (1)

- Annulment denied for non-disclosure of pre-marital relationshipDocument2 pagesAnnulment denied for non-disclosure of pre-marital relationshipShalom Mangalindan100% (1)

- Bambalan V MarambaDocument2 pagesBambalan V Marambamegawhat1150% (2)

- Macadangdang vs CA legal separation death spouseDocument13 pagesMacadangdang vs CA legal separation death spouseKye GarciaNo ratings yet

- Banez Vs BanezDocument2 pagesBanez Vs BanezLea Gabrielle FariolaNo ratings yet

- Laperal vs. KatigbakDocument2 pagesLaperal vs. KatigbakEdison Flores100% (2)

- SC overturns lower courts, rules both marriages void without judicial declarationDocument2 pagesSC overturns lower courts, rules both marriages void without judicial declarationAndrew CapiralNo ratings yet

- Macadaeg V MatuteDocument3 pagesMacadaeg V MatutealexjalecoNo ratings yet

- 01 Republic Vs IyoyDocument2 pages01 Republic Vs IyoyGeopano Luigi JrNo ratings yet

- SC reverses conviction of priest for violating marriage lawDocument1 pageSC reverses conviction of priest for violating marriage lawJoann LedesmaNo ratings yet

- 79.1 Enrico vs. Heirs of Sps. Medinaceli DigestDocument2 pages79.1 Enrico vs. Heirs of Sps. Medinaceli DigestEstel Tabumfama100% (1)

- Rosalia Martinez Vs Angel Tan 12 Phil 731 PDFDocument1 pageRosalia Martinez Vs Angel Tan 12 Phil 731 PDFJERROM ABAINZANo ratings yet

- Republic Vs DayotDocument1 pageRepublic Vs Dayotapi-27247349100% (1)

- 204 Moe v. Dinkins SeneresDocument2 pages204 Moe v. Dinkins SeneresChescaSeñeresNo ratings yet

- Eloisa Goitia vs Jose Campos marital support caseDocument1 pageEloisa Goitia vs Jose Campos marital support caseAysNo ratings yet

- Lapuz Vs EufemioDocument2 pagesLapuz Vs EufemioJosephine Huelva VictorNo ratings yet

- Vda. de Delizo Vs Delizo (1976) : ST NDDocument1 pageVda. de Delizo Vs Delizo (1976) : ST NDDiana HernandezNo ratings yet

- Matubis Vs PraxedesDocument1 pageMatubis Vs PraxedesDoms ErodiasNo ratings yet

- 50.1 de CAstro vs. Assidao-De Castro DigestDocument2 pages50.1 de CAstro vs. Assidao-De Castro DigestEstel Tabumfama100% (3)

- Mario Siochi vs. Alfredo GozonDocument1 pageMario Siochi vs. Alfredo GozonIkangApostolNo ratings yet

- Babiera V CatotalDocument2 pagesBabiera V CatotalDayday Able100% (1)

- Tongol Vs TongolDocument9 pagesTongol Vs TongollawsimNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court Rules Lack of Valid Marriage License Renders Marriage VoidDocument17 pagesSupreme Court Rules Lack of Valid Marriage License Renders Marriage VoidElms TondoNo ratings yet

- Case Digest Family LawDocument27 pagesCase Digest Family LawTrinca Diploma67% (3)

- Briones v. MiguelDocument3 pagesBriones v. MiguelAMBNo ratings yet

- Patricio vs. DarioDocument2 pagesPatricio vs. DarioHailey Raincloud100% (1)

- Almelor Vs RTC of Las Pinas GR 179620Document1 pageAlmelor Vs RTC of Las Pinas GR 179620Danica BeeNo ratings yet

- Arroyo vs. Vasquez de Arroyo DigestDocument1 pageArroyo vs. Vasquez de Arroyo DigestKlein Charisse Abejo100% (1)

- Pacete Vs CarriagaDocument1 pagePacete Vs CarriagaDoms ErodiasNo ratings yet

- SSS Pension DisputeDocument1 pageSSS Pension Disputesharon smithNo ratings yet

- Republic vs. Quintero-HamanoDocument3 pagesRepublic vs. Quintero-HamanoZachary KingNo ratings yet

- Ninal Vs Bayadog DIGESTDocument2 pagesNinal Vs Bayadog DIGESTMaicko PhilNo ratings yet

- WHEREFORE, The Petition Is GRANTED. The Assailed Order of The RegionalDocument1 pageWHEREFORE, The Petition Is GRANTED. The Assailed Order of The RegionalninaNo ratings yet

- Dela Llana Vs CoaDocument2 pagesDela Llana Vs CoaEarleen Del RosarioNo ratings yet

- Makalintal Vs PetDocument3 pagesMakalintal Vs PetEarleen Del RosarioNo ratings yet

- Makalintal Vs PetDocument3 pagesMakalintal Vs PetEarleen Del RosarioNo ratings yet

- SpamDocument1 pageSpamEarleen Del RosarioNo ratings yet

- JurisdictionDocument23 pagesJurisdictionEarleen Del RosarioNo ratings yet

- Conflict of LawsDocument4 pagesConflict of LawsEarleen Del RosarioNo ratings yet

- Summary of Jurisdiction of Philippine CourtsDocument13 pagesSummary of Jurisdiction of Philippine CourtsXavier Hawkins Lopez Zamora82% (17)

- Administrative Order No 07Document10 pagesAdministrative Order No 07Anonymous zuizPMNo ratings yet

- Poli Digests Assgn No. 2Document11 pagesPoli Digests Assgn No. 2Earleen Del RosarioNo ratings yet

- Shooter Long Drink Creamy Classical TropicalDocument1 pageShooter Long Drink Creamy Classical TropicalEarleen Del RosarioNo ratings yet

- Summary of Jurisdiction of Philippine CourtsDocument13 pagesSummary of Jurisdiction of Philippine CourtsXavier Hawkins Lopez Zamora82% (17)

- JurisdictionDocument26 pagesJurisdictionEarleen Del RosarioNo ratings yet

- Labor Case DigestDocument4 pagesLabor Case DigestEarleen Del RosarioNo ratings yet

- Transpo CasesDocument16 pagesTranspo CasesEarleen Del RosarioNo ratings yet

- People Vs FloresDocument21 pagesPeople Vs FloresEarleen Del RosarioNo ratings yet

- Tax DigestsDocument35 pagesTax DigestsRafael JuicoNo ratings yet

- 2007-2013 REMEDIAL Law Philippine Bar Examination Questions and Suggested Answers (JayArhSals)Document198 pages2007-2013 REMEDIAL Law Philippine Bar Examination Questions and Suggested Answers (JayArhSals)Jay-Arh93% (123)

- Red NotesDocument24 pagesRed NotesPJ Hong100% (1)

- A Knowledge MentDocument1 pageA Knowledge MentEarleen Del RosarioNo ratings yet

- Letter of Intent - OLADocument1 pageLetter of Intent - OLAEarleen Del RosarioNo ratings yet

- Labor CasesDocument55 pagesLabor CasesEarleen Del RosarioNo ratings yet

- Fire Code of The Philippines 2008Document475 pagesFire Code of The Philippines 2008RISERPHIL89% (28)

- TARIFF AND CUSTOMS LAWS EXPLAINED3.Enforcement of Tariff and Customs Laws.4.Regulation of importation and exportation of goodsDocument6 pagesTARIFF AND CUSTOMS LAWS EXPLAINED3.Enforcement of Tariff and Customs Laws.4.Regulation of importation and exportation of goodsEarleen Del RosarioNo ratings yet

- The New National Building CodeDocument16 pagesThe New National Building Codegeanndyngenlyn86% (50)

- Torts and Damages Case DigestDocument3 pagesTorts and Damages Case DigestEarleen Del RosarioNo ratings yet

- Public Corp Reviewer From AteneoDocument7 pagesPublic Corp Reviewer From AteneoAbby Accad67% (3)

- TARIFF AND CUSTOMS LAWS EXPLAINED3.Enforcement of Tariff and Customs Laws.4.Regulation of importation and exportation of goodsDocument6 pagesTARIFF AND CUSTOMS LAWS EXPLAINED3.Enforcement of Tariff and Customs Laws.4.Regulation of importation and exportation of goodsEarleen Del RosarioNo ratings yet

- 212 - Criminal Law Suggested Answers (1994-2006), WordDocument85 pages212 - Criminal Law Suggested Answers (1994-2006), WordAngelito RamosNo ratings yet

- Labor CasesDocument55 pagesLabor CasesEarleen Del RosarioNo ratings yet

- Biggest Loser ChallengeDocument1 pageBiggest Loser ChallengeEarleen Del RosarioNo ratings yet

- Here Comes The Bride Wedding Vocabulary PDFDocument2 pagesHere Comes The Bride Wedding Vocabulary PDFNeus Pous FlorNo ratings yet

- 10 - Chapter 4 PDFDocument66 pages10 - Chapter 4 PDFTwinkl MehtaNo ratings yet

- Courtship to Marriage: A 40-Character GuideDocument28 pagesCourtship to Marriage: A 40-Character GuideEllie LinaoNo ratings yet

- Culture WeddingDocument6 pagesCulture WeddingshazilaNo ratings yet

- Husband Wife JokesDocument3 pagesHusband Wife JokesRajan Bhatt, Ph.D (Soil Science)No ratings yet

- Paper Book For Civil Appeal: Lokmanya Tilak National Appellate Moot Court CompetitionDocument31 pagesPaper Book For Civil Appeal: Lokmanya Tilak National Appellate Moot Court CompetitionmanikaNo ratings yet

- Speakout DVD Extra Intermediate Unit 06 PDFDocument1 pageSpeakout DVD Extra Intermediate Unit 06 PDFShwe Maw Kun100% (1)

- Persons and Family Relations Midterms SyllabusDocument4 pagesPersons and Family Relations Midterms SyllabusMary Ann AlcantaraNo ratings yet

- Kinshipmarriageandthehousehold 170907030015Document35 pagesKinshipmarriageandthehousehold 170907030015Ronalyn CajudoNo ratings yet

- Father of The Bride Speeches: 4 Killer Tips That Will Make Your Speech Great!Document2 pagesFather of The Bride Speeches: 4 Killer Tips That Will Make Your Speech Great!Michael100% (2)

- Family Code NotesDocument26 pagesFamily Code Notesalyssa bianca orbisoNo ratings yet

- 100 - Borja Manzano V SanchezDocument1 page100 - Borja Manzano V SanchezTin MendozaNo ratings yet

- Wedding Budget Planner Tracks Expenses of Rs. 942,840 EventDocument5 pagesWedding Budget Planner Tracks Expenses of Rs. 942,840 EventNadeesha BandaraNo ratings yet

- Annulment, Divorce and Legal SeparationDocument12 pagesAnnulment, Divorce and Legal SeparationPrecious Rain GloryNo ratings yet

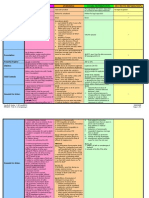

- PERSONS Marriage MatrixDocument6 pagesPERSONS Marriage Matrixsaintkarri100% (1)

- Canonical and Legal Aspects of MarriageDocument5 pagesCanonical and Legal Aspects of MarriageErwin Y. CabaronNo ratings yet

- DLL - Science 4 - Q4 - W4Document6 pagesDLL - Science 4 - Q4 - W4Errol Rabe SolidariosNo ratings yet

- Republic Vs Dayot DigestDocument3 pagesRepublic Vs Dayot Digestzyd100% (1)

- Leave and License AgreementDocument4 pagesLeave and License AgreementManishNo ratings yet

- My Wedding Budget: Total $Document4 pagesMy Wedding Budget: Total $Thanalachmy GopiNo ratings yet

- New Text DoddgggcumentDocument33 pagesNew Text Doddgggcumentsim2010simNo ratings yet

- The Case of Bombay High Court On Narasu Appa MaliDocument2 pagesThe Case of Bombay High Court On Narasu Appa Malimonali raiNo ratings yet

- Emancipation (1993) : Civil Law Bar Exam Answers: Family CodeDocument46 pagesEmancipation (1993) : Civil Law Bar Exam Answers: Family CodeLourdes Sta. MariaNo ratings yet

- Void and Voidable Marriages CasesDocument17 pagesVoid and Voidable Marriages CasescelNo ratings yet

- Yzabrielle Invitations: Wedding Details for Michael & JunaDocument2 pagesYzabrielle Invitations: Wedding Details for Michael & JunaYzaYzra CentsNo ratings yet

- Didactic Sequence: FamiliesDocument14 pagesDidactic Sequence: FamiliesClaudia FernándezNo ratings yet

- Guam Divorce and Separation Oct 2015Document4 pagesGuam Divorce and Separation Oct 2015Carl ReevesNo ratings yet

- Case Title: Pilapil Vs Ibay - Somera, GR 80116Document3 pagesCase Title: Pilapil Vs Ibay - Somera, GR 80116Jennica Gyrl G. DelfinNo ratings yet

- Un Employed But Qualified Wife Not Entitled To Maintenance PDFDocument4 pagesUn Employed But Qualified Wife Not Entitled To Maintenance PDFRanjan KumarNo ratings yet

- Warren Jeffs: Bigamous Marriages He Officiated or WitnessedDocument55 pagesWarren Jeffs: Bigamous Marriages He Officiated or Witnessedborninbrooklyn83% (6)

- How to Win Your Case in Small Claims Court Without a LawyerFrom EverandHow to Win Your Case in Small Claims Court Without a LawyerRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Learn the Essentials of Business Law in 15 DaysFrom EverandLearn the Essentials of Business Law in 15 DaysRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (13)

- Litigation Story: How to Survive and Thrive Through the Litigation ProcessFrom EverandLitigation Story: How to Survive and Thrive Through the Litigation ProcessRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Business of Broadway: An Insider's Guide to Working, Producing, and Investing in the World's Greatest Theatre CommunityFrom EverandThe Business of Broadway: An Insider's Guide to Working, Producing, and Investing in the World's Greatest Theatre CommunityNo ratings yet

- Crash Course Business Agreements and ContractsFrom EverandCrash Course Business Agreements and ContractsRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (3)

- Digital Technical Theater Simplified: High Tech Lighting, Audio, Video and More on a Low BudgetFrom EverandDigital Technical Theater Simplified: High Tech Lighting, Audio, Video and More on a Low BudgetNo ratings yet

- The Art of Fact Investigation: Creative Thinking in the Age of Information OverloadFrom EverandThe Art of Fact Investigation: Creative Thinking in the Age of Information OverloadRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Greed on Trial: Doctors and Patients Unite to Fight Big InsuranceFrom EverandGreed on Trial: Doctors and Patients Unite to Fight Big InsuranceNo ratings yet

- Courage to Stand: Mastering Trial Strategies and Techniques in the CourtroomFrom EverandCourage to Stand: Mastering Trial Strategies and Techniques in the CourtroomNo ratings yet

- Broadway General Manager: Demystifying the Most Important and Least Understood Role in Show BusinessFrom EverandBroadway General Manager: Demystifying the Most Important and Least Understood Role in Show BusinessNo ratings yet

- Starting Your Career as a Photo Stylist: A Comprehensive Guide to Photo Shoots, Marketing, Business, Fashion, Wardrobe, Off Figure, Product, Prop, Room Sets, and Food StylingFrom EverandStarting Your Career as a Photo Stylist: A Comprehensive Guide to Photo Shoots, Marketing, Business, Fashion, Wardrobe, Off Figure, Product, Prop, Room Sets, and Food StylingRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- What Are You Laughing At?: How to Write Humor for Screenplays, Stories, and MoreFrom EverandWhat Are You Laughing At?: How to Write Humor for Screenplays, Stories, and MoreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Independent Film Producing: How to Produce a Low-Budget Feature FilmFrom EverandIndependent Film Producing: How to Produce a Low-Budget Feature FilmNo ratings yet

- 2017 Commercial & Industrial Common Interest Development ActFrom Everand2017 Commercial & Industrial Common Interest Development ActNo ratings yet

- A Simple Guide for Drafting of Conveyances in India : Forms of Conveyances and Instruments executed in the Indian sub-continent along with Notes and TipsFrom EverandA Simple Guide for Drafting of Conveyances in India : Forms of Conveyances and Instruments executed in the Indian sub-continent along with Notes and TipsNo ratings yet

- How to Improvise a Full-Length Play: The Art of Spontaneous TheaterFrom EverandHow to Improvise a Full-Length Play: The Art of Spontaneous TheaterNo ratings yet

- Law of Contract Made Simple for LaymenFrom EverandLaw of Contract Made Simple for LaymenRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (9)