Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Beyond Legal Bindings

Uploaded by

flordeliz12Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Beyond Legal Bindings

Uploaded by

flordeliz12Copyright:

Available Formats

Beyond Legal Bindingness

Pgina 1 de 17

Beyond Legal Bindingness

Author

Hans Pijl [*]

1. Introduction

The human mind likes to think in binary contrasts: present and absent, light and dark, war and peace, health and sickness, sovereignty and submission, identity and division, hard and soft, Dionysian and Apollonian. [139] The first pole is sometimes connected with positive sentiments, the latter with less favourable ones. Not surprisingly, well drafted book titles, i.e. titles reflecting the essence of the universe contained in them, often embody this spirit: Jenseits von Gut und Bse (Beyond Good and Evil), Der Jasager und der Neinsager (The Yes-Sayer and the No-Sayer) and Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny (Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny). [140] Equally unsurprisingly, two of these works are by Brecht, an adept of the Marxist philosophy and its dialectical method. "Twos company, threes a crowd" - and where there are more related categories (the Good, the Bad and the Ugly), these are the omen of an unregulated, lawless world. We had better avoid entering into ontological discussions on the question of whether these pairs are the building blocks of reality or whether they are just our way of structuring reality: assuming, as we are children of the 20th century, that most of us have left natural law behind us and that we do not regard law as a gift from a deity, law is the creation of our own mind. The binary oppositions in this approach are products of our mind, children of our intellect that are always trying to make confusing reality understandable and manageable. We had also better avoid the question of whether the constant progress and the cohesion of international law are just a narrative, or whether the progress it seems to have made in the last 50 years after the disaster and disruptions of World War II is a mere coincidence, or a nave and incomplete perception. The fact is that the modern phase of history is marked by a process of international integration (torn of the iron curtain and globalization), and that this factual integration goes hand in hand with an enormous expansion of international agreements. In the traditional approach, international agreements are cast in opposite terms of legal bindingness versus legal non-bindingness. This Entweder-Oder opposition fits the needs of our structuring mind: a rule is either legally binding or non-binding, and there is nothing in between. Indeed, this distinction is still the paradigm, although it is clearly not the complete picture of state agreements. In Jenseits bindingness, there is a world of instruments (or just behaviour in general) that, though not legally binding, represent a variety of politically binding agreements between states. There are many rules which states perceive as imposing strong obligations on them, even when they are not legally binding, and there are others that have a much weaker character. The question of what is on the other side of the border of this land of non-binding law has recently received more detailed attention, [141] albeit that this waste land is far from having been explored scientifically in any depth. No clear criteria have been developed to date, and no scientific analysis has been made with a view to making a taxonomy of the concept of political bindingness. Commitments and obligations in this non-legal political realm are other than legal in nature, resting on a political rather than a legal basis. There may be no legal bindingness, but there may still be an incentive of some kind, weak or strong, to follow the legally non-binding rules for a number of reasons, such as the existence of an effective monitoring mechanism or peer review. Specifically in cases where the media "blame and shame" non-compliant behaviour, or where sanctions threaten the non-compliant state, the incentive to adhere to the rules may be strong. This is especially so when the rule in force reflects generally prevailing public opinion in a state (e.g. on the issue of human rights) so that, even if no legal basis exists (assuming that the state in question is not bound by human rights treaties), non-compliant behaviour might well trigger strong internal resistance, for instance in the event that the morally compelling, political instrument of the UN Declaration on Human Rights is not taken as the norm of state behaviour. A further example: even though the views of the Human Rights Committee (HRC) are not binding, a state would not do itself any favours by not taking the Committees views seriously and ignoring them. Political commitments of this kind, which do not have a basis in any classical treaty and which are not eligible for classification elsewhere in the list of Art. 38 of the Statute of the ICJ, may thus force a state to act as if it were bound by a treaty; and conversely, a weakly drafted treaty may well have no impact at all. In some cases, if certain conditions are met, a political obligation may transcend from the political realm to the legal realm. For instance, a political agreement may have been made in such circumstances that it must be regarded as a legal one (as the ICJ held in Qatar v. Bahrain), or a regime may have been created which is binding on the states involved despite the absence of a legally binding rule (e.g. because of expiry of the treaty). This was the case in the ICJs judgement in Libya v. Chad, where the fact that the border treaty had expired was

http://online.ibfd.org/highlight/collections/lsco/html/lsco_c06.html?q=soft+hard+non...

14/08/2013

Beyond Legal Bindingness

Pgina 2 de 17

held not to have any legal effect on the borders once set. Finally, behaviour expressing acceptance of a tacit rule may also make that rule binding, as was the case in the ICJs decision in Temple of Preah Vihear. But then, where should the Commentaries on the OECD Model Tax Convention, clearly an instrument which is not legally binding in terms of either text or context, be positioned? Is it to be considered only an instrument of a political nature or have the rules of the game raised the Commentaries to the realm of legally binding agreements? Apart from the legal dimension, there are various aspects that should be examined in order to be able to answer this question. Firstly, a proper grasp of international law is impossible without considering social and political backgrounds: a purely legal approach will be inadequate, as international law is deeply rooted in a sociological and political Umfeld. I shall discuss this specific environment in the paragraphs below and argue that it does not allow us to regard the Commentaries as legally binding instruments. Secondly, whatever the result of any examination of the non-legal aspects involved, in terms of legal doctrine the outcome will most likely be the same, i.e. the Commentaries role as a leading document in the interpretation of tax treaties cannot be underestimated, irrespective of the basic theoretical assumptions as regards the political or legal bindingness of the Commentaries. [142] Regrettably, for those who have great hopes of any judicial decision on the matter by an international court of law, their hopes are idle. It is not to be expected that a taxation matter will ever be referred to the ICJ under Art. 36(1) or under the declarations of Art. 36(2) of the Statute. [143] Thirdly, as a linguistic expression, the Commentaries under discussion cannot be considered as independent and standing alone; as an act of speech, they are embedded in a linguistic playing field, and can only be understood in an overall linguistic context.

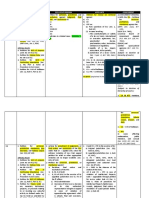

2. Sources of international tax law

Formal sources of legally binding and recognized international tax law are: (i) treaties, [144] e.g. bilateral tax treaties, and (ii) custom, [145] e.g. the taxation of diplomats. In defining the formal sources of international tax law, reference may be made to Art. 38 of the Statute of the International Court of Justice. Although the relevant provisions do not bind domestic courts, Art. 38, as a rule for the World Court, should be inspiring to the municipal judges, who are generally the bodies that deal with international taxation matters. The question of whether the Commentaries on the OECD Model Tax Convention can be regarded as customary law would require an extensive study, but consensus seems to exist that, as a whole, they cannot, because they do not meet the basic requirements of customary law: consistent practice and opinio juris. On the other hand, certain specific rules expressed in the Commentaries might be regarded as customary law or as having the potential of developing into such law. Art. 38 of the Statute also refers to "international custom as evidence of a general practice accepted as law". [146] If this category is taken to embody lawyers logic (e.g. the later rule or the more specific rule prevails), the Commentaries have no place there. If the category is construed as a conceptual reference to true principles of international law, certain rules of the Commentaries may be considered evidence of a general principle of tax law, if supported by established domestic practices and legal concepts, such as good faith. Good faith as a general principle of law could be the formal source to elevate the Commentaries to binding rules of law. This aspect will be discussed in greater detail below. It does not need much argument to disqualify the Commentaries for application under Art. 38(1)(d) of the Statute, which refers only to "judicial decisions and the teachings of the most highly qualified publicists of the various nations". The Commentaries clearly do not fall under this category. There is a wide variety of international rules that do not flow from the sources of law listed in Art. 38 of the Statute. Many of these stem from international agreements that do not constitute formal treaties and are not legally binding under the pacta sunt servanda rule of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties ("Vienna Convention"). Views of the Human Rights Committee, Resolutions by the General Assembly and mutual agreements under Art. 25 of the OECD Model Tax Convention also belong to this category. Even though these rules are not legally binding, there is a political commitment for states to act according to those rules, and normally no state ignores that commitment. states generally do not deny that they are parties to an agreement which requires them to act in a certain way, and in practice there is not much of a difference between acts emanating from legally binding rules and acts based on rules that are not legally binding. Such a difference will become visible, however, if state liability issues arise. Is the catalogue of Art. 38 of the Statute perhaps incomplete, and should other sources be added? Jus cogens apart (maybe not even jus cogens), this seems doubtful as the catalogue seems wide enough to also comprise sources not explicitly mentioned. Unilateral acts, for example, can be considered to impose a legally binding commitment on the state making the statement. The commitment arises from the general principle of good faith when "it is the intention of the state making the declaration that it should become bound according to its terms". [147] Resolutions by the General Assembly, as another example, may be binding rules based on customary law, even though they are mostly not so based (at least initially) because - as the ICJ has held - the mere recognition

http://online.ibfd.org/highlight/collections/lsco/html/lsco_c06.html?q=soft+hard+non...

14/08/2013

Beyond Legal Bindingness

Pgina 3 de 17

of certain rules by states does not in itself create international customary law. [148] It seems, therefore, that the classical list of Art. 38 of the Statute is well suited to respond to modern developments, and that customary law and general principles are sufficient. Perhaps, even jus cogens can be considered as falling under customary law (see, e.g. Art. 53 of the Vienna Convention). Politically binding instruments such as the Commentaries might also be considered as containing binding rules, namely when they are considered to fall under customary law or when good faith promotes them to the realm of legally binding rules. In legal terms, life would be much easier if all international instruments could be considered as either legally binding or not, and if this were the whole story. The binary approach is the lawyers condition humaine, and the wish to give all of those instruments a legally binding character (or not) is an understandable one. There can be no doubt, however, that in the current phase of international law the whole story has not yet been told. What is the complete story, then?

3. The rationale behind non-binding instruments

Under the paradigm of state sovereignty, with the state being an absolute power and primarily bound to nothing but itself, international law made slow progress in its relative - nowadays mostly superior - position to domestic law. In the more nationalistic phases of history (Moser, Hegel), international law was even subject to domestic law. And even nowadays, in many constitutional systems, international law does not have the position it deserves and is subject to a range of limitations. In the open Dutch system, for instance, the possibility of relying on international law is limited: under the Constitution, international law will only prevail over domestic law if the rule in question is apt to have direct effect, which means that it must at least be sufficiently specific. The sovereignty concept still positions states as fully independent international persons, subject to no rules other than those created by themselves and those accepted in their interaction with other states. Despite the growing process of internationalization and the increased complexities of the 21st century, this paradigm still reigns, and we are still living in a world where the will of the state forms the basis for the commitments assumed (voluntarism, consensualism). The growing process of internationalization and interdependence manifests itself in the explosion of newly created legally binding treaties between states on every new aspect of life. On the one hand, these treaties concern the interests of states as organizations per se (e.g. boundary treaties); on the other hand, they involve interests of the states nationals [149] (e.g. human rights treaties). To put it differently: on the one hand, states have an interest in regulating their interaction with other states in order to protect their own interests as states per se, and legal attunement helps create a well-functioning world order; on the other hand, states as collectives of individuals (including legal entities for the present purpose) should make their actions subject to individual needs, whether in the field of human law or on a more worldly level in the area of taxation. [150] The constitutional systems of democratic states in which proposed international law is subject to parliamentary approval are a reflection of those individual interests. If we consider the international collection of states as a real "world community" and take the responsibilities ensuing therefrom seriously, and if we then take a cosmopolitan view of international law, we must conclude that we cannot accept that legal obligations arise where the will of the state (the people) is absent. Yet, this will-based system has surpassed its efficiency in this globalizing world. The complicated domestic procedures required to bring international law into the domestic hemisphere form a serious impediment to balancing international relationships in a wide variety of fields ranging from peace, the environment, aviation and human rights to money laundering, taxation and cooperation. Making regulations exclusively by means of treaties would seriously overburden the offices of Foreign Affairs and would disengage the monitoring function of parliament. Treaties are cumbersome, unwieldy instruments to regulate the details of international interaction. In this vein, the last 50 years have shown a proliferation of legally non-binding instruments, with states circumventing onerous treaty procedures and making unofficial agreements to regulate interactions in a practical manner and avoid legal commitments which would require parliamentary approval. This has led to a system that - importantly - still allows parliaments to subject their states international policy to their scrutiny, and parliaments will most certainly make use of this power if they believe the area of regulation to be sufficiently important. We have seen this same development in many more or less important fields of law. As regards the Helsinki Final Act of 1975, for instance, the participating countries apparently did not want a final document that was more than just morally compelling. (One of the doctrinal positions on the legal dimensions of the relevant Accords is that they may develop over time into something more than a moral obligation. [151]) To mention a few other instruments that are not legally binding: the 1948 UN Declaration of Human Rights, the 1970 Declaration on the Principles of Friendly Relationships Among States, the European codes of conduct, and the guidelines, resolutions, declarations and recommendations of many international organizations, such as the International Atomic Energy Agency, the FATP, the Council of Europe, the OECD and the UN General Assembly. This phenomenon has not left international tax law untouched. In the context of the OECD and the United Nations, the informal Commentaries [152] were developed to foster unity in the conduct of states in international taxation matters. This was all the more necessary as the "hard" law of double tax treaties is open to

http://online.ibfd.org/highlight/collections/lsco/html/lsco_c06.html?q=soft+hard+non...

14/08/2013

Beyond Legal Bindingness

Pgina 4 de 17

interpretation and "soft" in its meaning, and leaves many issues to later adjudication. Where treaties are hard in terms of bindingness and soft (thus: manifold) in terms of meaning, the Commentaries are inversely proportional to these treaties in matters of interpretation. From an international cohesion perspective, this development can only be applauded. Instead of passively waiting for domestic judges to adjudicate international cases in the varying contexts of their differing domestic fiscal traditions and to actively bring uniformity to treaty application and interpretation, the states, united in the United Nations and the OECD, contributed to a more consistent worldwide understanding of tax treaties by explaining what they understood the treaty provisions to entail. Similarly to international law in general, the legal bindingness or non-bindingness of international tax law depends on the will of the state, but is also a matter of appreciation of facts and circumstances. The Commentaries, however, are generally seen as not having the effect of bringing themselves within the radius of legal commitment. That is not to say that the Commentaries do not have a normative impact on states or that states would be allowed to just disregard them in good faith. Legal practice and also the judiciary have recognized this in the importance they give to the Commentaries. The scope of a political commitment based on politically obliging instruments cannot go further than the circumstances dictate. If an instrument politically binds governments to implement a specific law, it is not easy to withdraw from that commitment, but a state would be able to defend its failure to pass the bill through parliament by making its parliamentary system an excuse for breaching its soft commitment (even though it may then be subject to peer pressure and "blaming and shaming"). Equally, a state whose executive (the government; see for the importance of the distinction between government and state 5.4.) has agreed to the Commentaries cannot be held liable if a domestic court of law interprets the treaty differently from the Commentaries. In practice, these legally non-binding instruments are also used where, in a multilateral context, no uniform norm can be said to have developed and where the soft codification of that norm in a political instrument (even if the norm is only accepted by a small majority of countries) can contribute to the progressive development of uniformity in the long run. The norm may result in bringing the dissenting states to exhibit conduct that is more in coherence with that norm. Reasons (sometimes overlapping) for entering into legally non-binding agreements include the following: (1) It is easier to reach agreement on instruments that are not legally binding, as the consequences of non-compliance are less serious and no issues of state responsibility will arise, which facilitates the unification of international behaviour. Legally non-binding instruments are flexible and can easily be changed. Moreover, the temporal scope of such changes is usually wider, as is the case with the Commentaries: where the interpretational scope of the Commentaries also covers the past, [153] a new treaty text typically applies to the future and has very limited retroactive effect. There have been seven changes to the Commentaries up to and including the year 1992. Changing a multilateral treaty with this frequency (the OECD Model Convention was originally intended to be a multilateral instrument) would lead to an awkward and complex variety in the bilateral relationships with numerous reservations by states which do not accept certain proposed changes. As international taxation is usually regulated in bilateral treaties, this would lead to a confusing jungle of bilateral agreements, which is clearly at odds with the proclaimed aim of the OECD "to harmonize existing bilateral conventions [...] and to extend the existing network of such conventions". [154] In the modern world of growing internationalization and interdependence, parliaments are prepared to give up their prerogatives regarding treaty amendments and to leave certain changes to the executive branch of government, which generally participates in supranational committees in that context. Parliaments specifically do this when the amendments concerned are regarded as less meaningful, e.g. because of their highly technical and complex nature (as is often the case in matters of aviation, atomic energy and the environment). The domestic constitutional systems usually provide for a simplified approval procedure in respect of such treaties. [155] There are also other fields, however, such as defence and taxation, where parliaments are less keen to waive their prerogatives and refer the matter to simplified procedures. This is because the treaties in question touch on the very existence of the state itself or have a direct impact on the states individuals. On the other hand, the dynamics in those fields would be seriously hampered if only instruments subject to parliamentary approval were used on a detail level. Therefore, the onerous ratification process is often overcome in such cases by a format whereby the parliamentary route is avoided (using instruments that do not require parliamentary approval). Legally non-binding, but politically binding instruments are a manifestation of international support and uniformity, and are an invitation to practitioners to review their standards. In practice, this is an effective way of coordinating international state behaviour. The judiciary contributes to this process by consistently characterizing the Commentaries as "very important" to the interpretation of tax treaties. Therefore, practically speaking, a non-binding instrument serves its purposes just as well as a binding treaty would do, and is thus an efficient form of dealing with limited human resources. In many situations, e.g. when there is not sufficient domestic political support for a certain rule, the time is not ripe for the specifics of a treaty.

(2)

(3)

(4)

(5)

(6) (7)

http://online.ibfd.org/highlight/collections/lsco/html/lsco_c06.html?q=soft+hard+non...

14/08/2013

Beyond Legal Bindingness

Pgina 5 de 17

Internationally, legally binding instruments are often preceded by a legally non-binding instrument, which can well serve to accomplish coordinated behaviour until the time is ripe to lay the rules down in legally binding instruments, namely when uniform application of the rule has created a generally accepted standard worldwide. It is the instruments function that determines its form: if efficient coordination can only be reached by legally non-binding instruments, that non-binding form shall be the form the instrument shall have. Reference is made in this regard to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA): the Nuclear Safety Convention and the Joint Convention on the Safety of Spent Fuel and Radioactive Waste Management were originally non-binding safety standards issued by the Agency. [156] (8) One of the important effects of standardization by international organizations such as the OECD is that the standards created reach beyond the limited group of Member countries. Where lack of local capacity (typical to many developing countries) may disenable non-Member countries to develop their own understanding of bilateral tax treaties, the Commentaries on the treaty provisions might help to overcome that problem. By that same token, signs of OECD influence can be found in the UNs Model Double Taxation Convention and Commentaries. (9) If international rules cannot be laid down in the form of hard rules, standardization can contribute to the creation of a level playing field, which is important to areas like money laundering or taxation in order to avoid an all too easy selection of states that apply the most relaxed international standards. (10) Confidentiality [157] also plays a role in the choice of non-treaties over treaties, as the latter category usually requires publication. In the Netherlands, for example, until a few years ago, a certain number of interpretative mutual agreements under Art. 25 of the OECD Model Tax Convention (i.e. Memorandums of Understanding on taxation) were never published in their original format, and only a summary of their contents was made known through ministerial decrees. [158]

4. Individuals in international law, state sovereignty, constitution

4.1. Individuals in international law

Rules of international law are pragmatic, flexible and dynamic, and they develop and change as time passes and as facts, circumstances and perceptions evolve. This applies to any subject of international law: the recognition of states, the position of individuals in international law or the bindingness of international instruments, the latter two subjects being of importance to the theme of this article. In 19th century philosophy, individuals were generally excluded from the group of addressees of international law, as may already be inferred from the then colloquial word for this branch of law, that is, the Law of Nations, which was law of nations, not of nationals. Where a rule of international law was to have an impact on the individuals of a state, domestic law would have to intervene. The Law of Nations was "a law for the international conduct of states, and not of their citizens", [159] to quote one of the followers of this doctrine. Under this perception of international law, rights and duties granted to individuals in treaties were granted under the municipal law of the states, and at the level of international law, individuals were merely objects. The doctrine recognized, however, that the concept was marked by an internal tension, and the language of treaties granting rights to individuals needed to be reconciled with the doctrines self-perceived prima facie concept: "Although such treaties mostly speak of rights which individuals shall have as derived from the treaties themselves, this is nothing more than an inaccuracy of language. In fact, such treaties do not create these rights, but they impose the duty upon the contracting states to call these rights into existence by their Municipal Laws." [160], [161] This view changed in the 20th century, when treaties were deemed capable of granting rights to individuals directly (the individual beside the state as a subject of international law), and when individuals gradually - albeit still only in part - received a procedural tool to make their rights effective by taking action directly against the defaulting state without having to rely on diplomatic intervention by their home state. Lauterpacht saw this procedural development as confirmation of the substantive rights individuals always had, [162] and regarded diplomatic protection as a tool for the benefit of the individual rather than the state. Rosalyn Higgins [163] took this one step further. She proposed abandoning the dichotomy between subject and object of international law and regarding the position of individuals and that of the state on an equal footing, on the basis of the participant concept. Rather than considering the state as the only relevant stakeholder in international law, a distinction at the international level should be made between typical state interests (in areas like boundary questions and sea law) and typical individual interests (protection of property, human rights law, personal treatment and fairness in cross-border business transactions). In her view (which is indeed quite helpful), international law has an open texture, able to protect the interests of all, including where they clash. In the 19th century view on international law, breaches of treaties, irrespective of the treaty area covered, only constituted a breach against the state, as the sole subject of international law. In the modern view, treaties pivoting around individuals (tax treaties, investment treaties, human rights treaties, and other treaties typically aiming at individual stakeholders) primarily confer rights on individuals, and any damage done is primarily individual damage and not state damage. Whether this can be taken so far that the state is not a participant in such matters at all falls outside the scope of this article, [164] but, in actual practice, states do take a passive attitude in taxation matters and do not pick up possible breaches of a tax treaty under diplomatic protection. In

http://online.ibfd.org/highlight/collections/lsco/html/lsco_c06.html?q=soft+hard+non...

14/08/2013

Beyond Legal Bindingness

Pgina 6 de 17

cases where foreign taxation is perceived as unjust, they prefer to leave the solution to the individuals, and taxpayers normally address the courts of the other state instead of filing action in their own state and asking that state to intervene. [165] Noticeably, for instance, the state complaint procedure under human rights treaties is hardly ever invoked. As for tax treaties, there is no such thing as an exclusive interest of individuals that dominates the interest scale; the interest of the state in cases of breach is also clearly present: even though the state steps back in cases where a direct loss is caused to individuals (the individuals direct loss appears to take precedent over the states indirect loss), the state does have a direct interest also, because its own taxation status under these treaties is concerned, e.g. in the context of abuse of treaty. Under tax treaties, therefore, the individual cannot be regarded as the only direct stakeholder: clearly the state itself has a direct interest as well. As the participant system under taxation treaties affects both state and individual directly, these treaties may be called hybrid in terms of the interests involved. states as such have an interest in protecting their taxation power (e.g. in deciding when to refrain from taxation under treaties, or in the area of abuse of treaties, in cases where improper tax planning may lead to an inequitable result), whilst individuals have a simultaneous interest in giving the treaty the desired effect. Where an individuals act in this hybrid system is typically directed at defending his or her own interest, the states reaction is potentially ambiguous, as it may entail the protection of the taxpayer, but also that of its own interests. It is precisely for this reason that the Commentaries are ambiguous also: as a product of the executive alone, they are apt to take the interests of the state and those of the individuals as paramount. The states reactions may not be difficult to classify. For instance, the change made to the Commentaries in response to the Philip Morris judgements, in which the Italian Supreme Court gave the definition of permanent establishment a scope that went beyond the normal interpretation of that term, may be regarded as a response in favour of the individual. [166] On the other hand, should the Commentaries ever defend the position that legal bindingness as a criterion for the creation of an agents permanent establishment in Art. 5(5) of the OECD Model Tax Convention is not sufficient, and that an economic criterion should be assumed to support the rationale of that provision as well, that position will have to be regarded as a statement made in the interest of the states as such. The abuse of law paragraphs in the Commentaries, or the interpretation of employer in Art. 15 as employer in a substantive sense, should be considered as being of the same category. In such cases, where a statement in the Commentaries potentially entails not only a material, direct interest for the state as a participant in this system, but also for its individuals/taxpayers as stakeholders, the proper approach in attributing interpretational force to the legally non-binding Commentaries would be a careful weighing of the interests of the state against those of the taxpayer. [167] No problems will arise if the interests of the state and the individual coincide. A problem does arise, however, if the interests of the state and those of the individuals conflict. Then, the question arises as to whether the system of international law as perceived can be such that the individual, as a principal participant in this system, can be bound by an agreement that puts the interests of the state first. This question can be answered as follows. In matters of taxation, the OECD Member countries have agreed on two instruments. One of them is a tax treaty, which is legally binding on all parties thereto (and, through the interaction of the pacta sunt servanda rule and the domestic treaty approval system, on their individuals as well). The other instrument, the Commentaries, is not legally binding, but merely creates a political agreement at executive level to interpret the tax treaty as much as possible in light of that legally non-binding instrument. In an international participant system, that latter instrument cannot become binding on the individual participants. The Commentaries can well give rise to a waiver of rights at state level, but not as far as the individuals are concerned. It also follows from the system of international law that its technologies (such as acquiescence and estoppel) cannot be used in such a way as to disrupt this balanced system.

4.2. State sovereignty

In the matter of the Commentaries and the basic OECD Recommendation, the Member countries have made use of every linguistic tool at their disposal to ascertain that the Commentaries are not legally binding on the states (see 5.) and that the Recommendation only creates a political commitment which essentially only binds the executive to fulfil its obligations. The states have thus given up their sovereignty to a limited political extent. Is it defensible under the circumstances discussed in 5. that the freedom of the Member countries to act is more limited than follows from the Recommendation? This question essentially touches on the scope of sovereignty, especially in light of the scope of the sovereignty of other states. Basically, sovereignty is unlimited (Lotus principle), which is reflected in many cases decided by the ICJ. Restrictions of that sovereignty can only be accepted where there is convincing evidence. And if any such restrictions exist, they must be interpreted narrowly. Where two sovereignties are brought into the equation, however, and a conflict arises, the two unlimited environments must somehow be reconciled. This could be done by referring to overriding general principles of international law, equity and good faith, as was done in a number of territorial disputes. There, those factors were made specific by reference to the geological situation, the unity of the mines, and proportionality

http://online.ibfd.org/highlight/collections/lsco/html/lsco_c06.html?q=soft+hard+non...

14/08/2013

Beyond Legal Bindingness

Pgina 7 de 17

between the continental shelves allocated to the contesting parties (North Sea Continental Shelf cases) or to the "equitable result" (Tunisia-Libya Continental Shelf case and the Libya-Malta Continental Shelf case). All of this involves a balancing act between the conflicting claims of the states involved. [168] In cases as described above, limitations to sovereignty are necessary when the sovereignty of State A collides with the sovereignty of State B. Where no claim is made in that respect, however, and where the states themselves agree on a mutual delimitation of the rights and duties they have created with the Commentaries, the concept of sovereignty would be limited unduly and without precedent if the states themselves have reached agreement on the scope of the political commitment they have assumed.

4.3. The rule of law and domestic practices

It would be contrary to many constitutional systems for a state to be granted power to conclude tax treaties or other legally binding agreements without having consulted parliament or having obtained parliamentary approval. In any case, in the Netherlands, the Minister of Finance never briefed parliament that in approving the treaty, it also approved the fact that the treaty should be read in the vein of the Commentaries. In Para. 2.2 of the General Tax Treaties Policy Paper, [169] the State Secretary instead explained that the Commentaries served as a guideline only (Dutch richtsnoer) in the interpretation of treaties, without claiming that the Commentaries had the status of an instrument entailing heavier obligations for the Netherlands. This was confirmed in the same paragraph of the Policy Paper: the "Netherlands" (in light of the subsequent reference to the judiciary, this is obviously the executive, i.e. the tax administration) "as well as" the Dutch judiciary attach "great importance" to the Commentaries. [170] As far as I know, other states (Executives) take the same approach of the Commentaries being guidelines, and other domestic courts also give the Commentaries only "great importance". Assuming that similar rules exist elsewhere, it would be contrary to the basic democratic system of the OECD Member countries if we were to accept that rules not approved by parliament would be binding on the population. Of course, a state cannot defend itself against a violation of international obligations by referring to its domestic law (Art. 27 of the Vienna Convention and Art. 3 of the Articles on the Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts). But this is a completely different issue that will not be discussed here. The point is that in light of the existing constitutional systems (facts for international law), the interpretation of the Recommendation as an instrument creating legally binding obligations, which implies a breach of the constitutional systems, cannot be correct.

5. The Recommendation and the annexed Commentaries

5.1. The Recommendation as a legally non-binding instrument

A treaty (Art. 2(1)(a) of the Vienna Convention) is legally binding on a state (Art. 26 of the Vienna Convention). Whether or not an instrument is a treaty depends on the intention of the states, which can be inferred from certain structural and linguistic characteristics given to the treaty. [171] There is no clear-cut line, however. In several cases (Qatar v. Bahrain, Aegean Sea), the basic issue was whether the disputed instrument should be considered as legally binding upon the states. In some other cases, there was clarity about the instruments status as not legally binding, but the question arose as to whether the conduct of states (through an act or omission) could be such that they could not justifiably claim that they were not legally bound (Temple of Preah Vihear). In these exceptional cases, the disputed instrument was regarded as legally binding, and the state concerned could not claim that it was not bound. However, these rather special cases do not detract from the general rule that consensus is the basis for legal bonds between states. If there is no such consensus, and if the will to be only politically bound is present, this will should be the starting point. Elevating an instrument of this type to the sphere of legal obligations must have a solid evidential basis. The Commentaries are a Recommendation, which is a legally non-binding instrument. This follows from Art. 5 of the Convention on the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development: [172] In order to achieve its aims, the Organisation may: (a) take decisions which, except as otherwise provided, shall be binding on all the Members; (b) make recommendations to Members, and (c) enter into agreements with Members, non-member States and international organisations. The specific Decisions, Recommendations and other types of OECD instruments in force are available on the OECD website, [173] which elsewhere confirms: Recommendations are not legally binding, but practice accords them great moral force as representing the political will of Member Countries and there is an expectation that Member Countries will do their utmost to fully implement a Recommendation. Thus, Member Countries which do not intend to do so usually abstain when a Recommendation is adopted, although this is not required in legal terms. The binding nature of instruments generally follows from facts and the language used. As to the language, importance can be attached to provisions regarding entry into force, state responsibility, termination, financial contribution and obligating terminology like "shall", "agree", "rights", "obligations". [174] As to other verbal

http://online.ibfd.org/highlight/collections/lsco/html/lsco_c06.html?q=soft+hard+non...

14/08/2013

Beyond Legal Bindingness

Pgina 8 de 17

indicators of legal non-bindingness, states often expressly state that the instrument is politically binding, or that it is not legally binding, or that it is not eligible for registration with the United Nations Secretariat, etc.

5.2. The will as a basis for bindingness and the European Commissions view on OECD Recommendations

The basis of bindingness is essentially the intention of the states. Interestingly, a few years ago, the General Secretariat of the Council of the European Union asked the Member States how they would define the status of their international instruments, concluding that a proper distinction between binding and non-binding instruments could only be made on the basis of an analysis of the will of the states (only the Netherlands did not respond to the relevant questions in Para. I of the questionnaire): Le critre de distinction des instruments juridiquement non obligatoires par rapport aux instruments juridiquement obligatoires se fonde dans tous les pays, sauf le Portugal, sur lanalyse de lintention, manifeste par les parties ou resultant du texte de laccord, de donner laccord une force juridique non obligatoire. [175] In his Opinion of 16 December 1993, [176] Advocate General Tesauro applied similar criteria in establishing whether an agreement between the European Commission and the United States [177] was binding. He also considered the will of the parties to be decisive, and there was no doubt on this point in the matter at hand, as it had been the expressed wish of the Commission to conclude a legally binding instrument. To support his argument, the AG also referred to some textual clauses and concluded that the termination clause confirmed the expressed will to enter into a legally binding agreement. Of interest in both the case at hand and in the context of the legal status of OECD Recommendations were the Commissions reasons to enter into an agreement with the United States. I quote more extensively, to make clear that the Commission took the position that OECD Recommendations have no legal effect: 2. It is appropriate to begin by recalling the circumstances of this dispute, and briefly to recapitulate the events which led to the conclusion of the Agreement in question. Certain Council of the OECD recommendations, concerning the application of procedural machinery for notification and consultation which the Member States have used on several occasions, have a bearing on the issue of the so-called extra-territorial application of the rules of competition and the problems which may arise therefrom as regards the relationship between different kinds of legislation of different origin. In particular, it is necessary to bear in mind the Recommendation of 21 May 1986, which amended and replaced the previous Recommendation of 25 September 1979 concerning cooperation between Member countries on restrictive business practices affecting international trade. Equally significant is the later Recommendation of 23 October 1986 concerning cooperation between member countries "in areas of potential conflict between competition and trade policies". It is precisely the OECDs 1979 recommendation, as amended in 1986, which served, according to the Commission itself, as a frame of reference for the definition of some of the issues relating to the extraterritorial application of the rules of competition which frequently arose between the United States and the EEC and were subsequently resolved under the contested Agreement. 3. Noting that the changes which had occurred in the international economy in recent years called for more ambitious objectives, in particular the drawing up of a "legally binding document rather than a non-binding recommendation", with a more incisive and innovatory content, (4) the Commission suggested to the United States authorities, in the course of meetings held at the end of 1990, the possibility of negotiating an agreement formalising relations between them, hitherto founded on a voluntary basis within the context of OECD recommendations, with a view to establishing closer cooperation based on a binding act.

5.3. Linguistic indicators of the level of political bindingness of recommendations

In the field of legally non-binding recommendations, no efforts have been made to date (as far as I know) to make a classification on a scale of political bindingness. It might be possible to analyse non-binding agreements with a view to drawing up a taxonomy in which some of these instruments are classified as imposing a heavier political burden than others on the addressees of the recommendations. A further examination of this issue does not fit within the scope of this article, but as a working hypothesis, some recommendations may well be considered to have been drafted in wordings which imply a more stringent political obligation for the Member countries than others. For example, the wording of the recommendation [178] under discussion in 5.1. [179] is weak in character ("should", [180] "as ... as possible"): A. POLICY PRINCIPLES TO STRENGTHEN COMPETITION IN NATIONAL AND INTERNATIONAL MARKETS a) Trade policy measures affecting competition

http://online.ibfd.org/highlight/collections/lsco/html/lsco_c06.html?q=soft+hard+non...

14/08/2013

Beyond Legal Bindingness

Pgina 9 de 17

1. Member governments should undertake, on the basis of the attached checklist, as systematic and comprehensive an evaluation as possible of proposed trade and trade-related measures as well as of existing measures when the latter are subject to review [...] Aust [181] also places the term "should" (and "will") at the weaker end of bindingness, whilst placing more stringent modes of verbs, such as "shall", at the opposite end. Aust suggests in this context applying the treaty interpretation rules of the Vienna Convention by analogy on MOUs - Memoranda of Understanding (legally non-binding) - as far as those rules are not at variance with the non-legally binding nature of such instruments. [182] This is an acceptable proposal. Building on this hypothesis, some observations are in order. Although the majority of the OECD instruments reviewed offer confirmation of the hypothesis, there are some remaining issues that merit closer attention, such as the question of why OECD Recommendations to introduce legislation are addressed mostly to the states, whereas recommendations to conclude treaties are generally addressed to the governments of the states. Noticeably in this regard, legally binding decisions (there are about 20 of them on the OECD website [183]) are practically always directed to the states (as subjects of international law), not to the executive branch of the state, the government. Almost without fail, the decisions are phrased as follows: "THE COUNCIL (...) DECIDES that Member Countries (...)". Where a form different from this classical form is used, the decisions refer to "states" or use other verbal formulae to refer to the Member countries, and only exceptionally speak to addressees other than the states. [184] It follows from the nature of decisions as being legally binding on the Member countries and triggering state responsibility in case of non-compliance that these international instruments address the Member countries themselves. Of equal importance is the fact that the texts of the over 100 recommendations on the OECD website are more diversified in nature. They are often addressed to the "Governments of Member Countries". The standard text here is "THE COUNCIL (...) RECOMMENDS the Governments of Member Countries (...)" or similar wordings with the same tenor. There are also a number of recommendations that are addressed to the "Member Countries", just as the decisions. The scope of this article does not leave room for any further examination of the issue, but it seems (numerically speaking) that, where domestic legislation is required, the addressee is generally the Member country, whereas in cases where day-to-day conduct is involved, the government is the preferred addressee. Limiting my examples to recommendations to introduce legislation in the field of taxation, I would refer to the Recommendation on the Tax Deductibility of Bribes to Foreign Public Officials (C(96)27/Final of 11 April 1996), the Recommendation concerning Tax Treaty Override (C(89)146/Final of 2 October 1989), [185] and the Recommendation on the Use of Tax Identification Numbers in an International Context (C(97)29/Final of 13 March 1997), which are all directed to the Member countries. On the other hand, recommendations prescribing certain conduct are generally addressed to the executive branch, i.e. the government of the Member country. In international law, the role of governments differs from that of the states, as may also be inferred from the doctrine on the recognition of states and governments. Thus, interestingly, a number of recommendations on taxation (one of them being the Recommendation on the OECD Model Tax Convention and the Commentaries, discussed in this article) are addressed to the government. Admittedly, however, things are not always clear-cut. There are also recommendations that are addressed to the governments but nonetheless recommend a legislative amendment. [186] Still, on a general plane, recommendations addressed to the governments appear to be more political in nature than recommendations addressed to the Member countries. This may, perhaps, be useful in a classification of recommendations according to a scale of political bindingness. There are a number of recommendations in the field of taxation that fit into the model in terms of requiring specific conduct and being addressed to the government, such as the Recommendation on the Determination of Transfer Pricing between Associated Enterprises (C97)144/Final of 24 July 1997), which prescribes certain conduct on the part of tax administrations and requests that governments develop the cooperation between their tax administrations on a bilateral or multilateral basis. Clearly, this Recommendation hovers at the executive level and does not involve the states themselves. By the same token, the Recommendation cannot possibly bind the courts in the adjudication of legal disputes before them. Similarly, the Recommendation concerning the Attribution of Income to Permanent Establishments with respect to the Model Tax Convention on Income and Capital (C(93)147/Final of 26 November 1993) merely recommends that in the application of tax treaties, the governments of the Member countries adhere to the recommendations of the Report on the Attribution of Income to Permanent Establishments. The Recommendation on the Granting of Tax Sparing in Tax Conventions (C(97)184/Final of 23 October 1997) recommends that the governments of the Member countries follow the recommendations set out in the Tax Sparing Credit Report when negotiating and concluding tax treaties. Possibly, the latter Recommendation to the Governments correctly reflects the common practice in states, i.e. that the executive is primarily responsible for the conclusion of treaties. By the

http://online.ibfd.org/highlight/collections/lsco/html/lsco_c06.html?q=soft+hard+non...

14/08/2013

Beyond Legal Bindingness

Pgina 10 de 17

same token, this applies to point 2 of the Recommendation concerning the OECD Model Tax Convention, as further discussed in 5.4. Generally, Recommendations addressed to the governments of the Member countries are in conflict with Art. 5 of the Convention on the OECD, which provides that decisions as well as recommendations are directed to members. The question arises whether naming governments as addressees of recommendations rests on a constitutional flaw or whether the difference between Member countries and governments is not in any way meaningful. As to the latter possibility, I consider it illogical to assert, on the one hand, that decisions must be (and are) addressed to the states, which would make systemic sense (as discussed above), and, on the other, that the wording in recommendations is a matter of coincidental inconsistency (although non-binding instruments may suffer from some loose use of words, as discussed in 5.4.). As regards the possibility of an OECD constitutional flaw, I believe that OECD practice must be paramount in our evaluation of recommendations addressed to the governments. OECD practice has developed a number of instruments (declarations, arrangements and understandings, and even international agreements) in addition to the instruments listed in Art. 5 of the Convention on the OECD. I will leave this matter for now, however, as it is less relevant to the subject matter of this article: even if recommendations directed to the governments are not to be regarded as "recommendations made to Members" as referred to in Art. 5 of the Convention on the OECD, they are still international agreements, and as legally non-binding instruments a fortiori, but politically binding in any case, they give rise to the same questions regarding political bindingness as regular "Constitutional" recommendations.

5.4. The Recommendation concerning the Model Tax Convention

The Recommendation concerning the Model Tax Convention on Income and on Capital (C(97)195/Final of 23 October 1997) makes the following recommendations to the executive branches (the governments) of the OECD Member countries - and not the Member countries themselves (quoted as far as relevant here): 2. When concluding new bilateral conventions or revising existing bilateral conventions, to conform to the Model Tax Convention, as interpreted by the Commentaries thereon; 3. That their tax administrations follow the commentaries on the Articles of the Model Tax Convention, as modified from time to time, when applying and interpreting the provisions of their bilateral tax conventions that are based on these Articles. If this Recommendation is given the grammatical interpretation it deserves (see Aust, quoted above, on interpreting MOUs - Memoranda of Understanding - in line with the canon of interpretation according to the Vienna Convention), the executive must be deemed to be under a political obligation to "conform to" the OECD Model Tax Convention in the specific treaties they negotiate and conclude. An analysis of the hardness of this obligation immediately shows that it is not hard at all considering the practice among countries of making treaties that considerably deviate from the OECD Model Tax Convention [187] and the way in which other OECD Member countries react to this behaviour. For example, the Netherlands did not make any reservation in the OECD Commentaries with regard to its wish to include a deviating provision, i.e. Art. 13(5) of the Dutch Model Treaty concerning the taxation of substantial interest holdings. [188] This confirms that the Netherlands does not regard the Recommendation as a legally binding instrument (see the guideline function expressed in the Policy Paper mentioned in 4.3.). Therefore, even on the legally non-binding, political side of bindingness, the obligation is not considered to be really strong. As for the reaction of other OECD Member countries, the lack of any known international protest against the Dutch practice shows that they also treat the binding force of the Recommendation as relative. Probably, the reason behind this matching sender-recipient phenomenon is that the Recommendation is based on the principle of "comply or explain" and that treaty negotiators must only do their best to "conform to" the OECD Model Tax Convention but may deviate from it when they believe such a deviation to be appropriate for any reason. I will further expand on the meaning of conform to in the paragraphs below. An equally important aspect is the fact that it is the executive (the government) that carries the political obligation of the Recommendation, not the state. If the state deviates from the text of the treaty concluded (e.g. as a consequence of the Parliamentary approval process or as a consequence of a judicial decision), no breach of this political obligation will arise as long as the government can prove that it acted in good faith and did its utmost to conform. As for the latter part of obligation 2 set out in the Recommendation, i.e. the obligation to "conform to the Model Tax Convention, as interpreted by the Commentaries thereon", the same issue arises. Limiting myself at this stage to the literal text of the Recommendation, I conclude that it is only the government that is politically bound to conform, and that the state (in its holistic inclusion of parliament and judiciary) has discretion to deviate. Thus, although the Recommendation may impose a (politically) binding obligation on the government to conform to the Model Tax Convention, as interpreted by the Commentaries, when concluding tax treaties, it does not impose on

http://online.ibfd.org/highlight/collections/lsco/html/lsco_c06.html?q=soft+hard+non...

14/08/2013

Beyond Legal Bindingness

Pgina 11 de 17

parliament the duty to take the Recommendation into account. At the end of the day, it is also the judiciary, which sets the ultimate coping stone in the masonry of international tax law, that has its hands free. There is yet another grammatical issue that arises in the interpretation of the term conform to. [189] Like so many words, which are but linguistic sieves through which many meanings may pass, this term is hybrid in nature rather than one-dimensional. Conform may be taken strictly, inferring a strict and complete adaptation to the norm, but may equally be understood as conferring a meaning that has a less far-reaching scope, i.e. as a general guideline, such as the OECD Model Tax Convention as interpreted by the Convention. Another possible interpretation, in my mind, would be that actors must act in conformity with some pre-existing norm but nonetheless have room for their own deviating conduct, provided that the essential elements are complied with. If this more relaxed interpretation of conform to can be held to pass the test of linguistic criticism as regards the question as to what the obligations under the Recommendation entail, no further reference need be made to the addressee of the Recommendation or to the social environment where deviations are accepted: the mere language gives the Member countries the necessary leeway to attend to their own needs. There is also a point of a teleological nature. The Recommendations Preamble reads as follows: Considering also the need to harmonise existing bilateral conventions on the basis of uniform principles, definitions, rules, and methods and to extend the existing network of such conventions to all Member countries and where appropriate to non-member countries; Considering further the need to encourage the common application and interpretation of the provisions of tax conventions that are based on those of the Model Tax Convention on Income and on Capital (hereinafter referred to as the "Model Tax Convention") [...] The most logical interpretation of the first paragraph is to explain "harmonise existing bilateral conventions on the basis of uniform principles, definitions, rules, and methods and to extend the existing network of such conventions" as referring to the Recommendations instruction to "conform to the Model Tax Convention" when concluding new treaties or revising old ones (Para. 2 of the Recommendation quoted above). Indeed, there are valid, practical reasons [190] for having the 2,500 treaties shaped according to a similar pattern. "To harmonise the treaties" and "to extend the existing network of such conventions" can only be understood as referring to the treaties themselves and as imposing a more or less strict task to harmonize what is there and to extend that in the same line. The second paragraph focuses on the application and interpretation of the treaty articles. Instead of making an equally strict statement, however, the paragraph merely sets the task of "encouraging" the common application and interpretation of the treaties. Considering the context, I would bring the words "as interpreted by the Commentaries thereon" within this same, relatively non-compelling atmosphere of "encouragement". A less benevolent interpreter might claim, however, that the text of the actual Recommendation is clear and that, despite the arguments above, the text plainly obliges states to interpret treaties in strict conformity with the Commentaries. I would respond to any such claim by making a point to which Aust also drew attention. There are dangers involved in creating political obligations by MOUs, [191] one of them being the bias to a somewhat careless drafting of these texts supported by the sentiment that, as these texts are legally non-binding, the risk of flaws in their drafting is limited anyway. At the same time, as noted above, the legal non-bindingness serves to the advantage of MOUs, because binding treaty texts are generally examined with a fine-tooth comb before they are signed, and often take a very long time to come into existence (if at all). I have no problem admitting to the same interpreter that a different text would have been conceivable and that the text as it exists may well lead to inappropriate conclusions if a narrow [192] grammatical approach is followed. As discussed, however, there is an overwhelming number of arguments that should bring the interpreter back on track, and there can be little doubt about the role of the Commentaries in the Recommendations paragraph: the Recommendation politically binds the executive (and no one else), but does leave the executive some room for manoeuvre, to either follow or deviate from the OECD Model Tax Convention and to apply and interpret the Convention according to the Commentaries. As an issue of contextual interpretation (I again refer to Austs suggestion of interpreting MOUs according to the Vienna Convention): the interpretative value of the context of the Recommendation has not been given sufficient merit in the discussion about the nature of the obligation. "The Model Tax Convention" is an Annex to the Recommendation (see the publication on the OECD website). The Annex as presented on the website is called the "Model Tax Convention on Income and on Capital" and represents what is usually known as the "Introduction". [193] Analysing the cohesion between Introduction, Model Tax Convention and Commentaries, I conclude that the Introduction and Model Tax Convention should be regarded as a whole, and that the Commentaries are a separate document. As it is, the Introduction is presented as an Annex to the Recommendation on the website, [194] and thus forms part of the interpretational context of the Recommendation. Quoting from Para. 28 of the Introduction: "Although the Commentaries are not designed to be annexed in any manner to the conventions signed by the Member countries, which unlike the Model are legally binding

http://online.ibfd.org/highlight/collections/lsco/html/lsco_c06.html?q=soft+hard+non...

14/08/2013

Beyond Legal Bindingness

Pgina 12 de 17

international instruments, they can nevertheless be of great assistance in the application and interpretation of the conventions and, in particular, in the settlement of any disputes", and from Para. 29.1: "Tax officials give great weight to the guidance contained in the Commentaries", I would argue that these statements should be given the required weight in the contextual interpretation of the words of the Recommendation. Indeed, by analogy to the Vienna Convention, the Commentaries constitute an instrument under Art. 31(2)(b) of the Vienna Convention: "any instrument which was made by one or more parties in connection with the conclusion of the treaty and accepted by the other parties as an instrument related to the treaty". In my view, the interpretation of the Annex can only confirm that the status of the Recommendations second recommendation on the conclusion of treaties "as interpreted by the Commentaries thereon" is a weaker form of political obligation. As an aside, international organizations employ all types of review mechanisms, either treaty-based or unofficial. These mechanisms may take the form of reporting, data collection, monitoring, sending of reporters, peer review, peer pressure, etc. [195] Annex A to the OECD study on internal steering instruments [196] contains an inventory of OECD Monitoring and Surveillance Activities. According to this Annex, monitoring also takes place on the OECD Model Convention on Income and on Capital, with the OECD Model Convention acting as the policy requirement/guideline. To my knowledge, there is no formal reporting procedure regarding the outcome of this monitoring process, so that the exact scope cannot be gauged. Interestingly, however, only the Model Tax Convention is mentioned in this regard, not the Commentaries. If it is true that the OECD Model Tax Convention is the only source for monitoring, this contributes to the perception that the Member countries regard the Commentaries as a secondary source of information. [197]

6. Good faith, estoppel and acquiescence

To my mind, there are no real and compelling grounds for giving the Commentaries a higher status than they currently have as a political commitment. If the Council exhibits proper caution and refrains from statements in the Commentaries that create an irreconcilable tension between treaties and Commentaries, the political bindingness of the Commentaries clearly suffices to give the Commentaries their effect as a guideline for applying and interpreting treaties in an ever-changing economic environment. Should any tension arise, however, I trust that the considerations above are sufficiently convincing to conclude that the Commentaries must give way to a proper interpretation of the treaty. However, as noted by Aust, [198] there can be no doubt that MOUs may become legally binding if certain conditions are met. The same applies to the Commentaries, but this does not detract from the basic starting point that the Commentaries are an important, political source of information, but are not a legally binding instrument, as is confirmed by the OECD Convention, the Recommendation, and the Commentaries themselves, as well as the domestic practices concerning treaty approval, the declarations of domestic governments, court judgements and the views of the EC Commission. It is in this legal and factual, social and linguistic environment that the possible role of good faith and its emanations of estoppel and acquiescence should be considered. Acquiescence ("action brings reaction", "silence means consent") rests on the principle that where a state remains silent in response to another states claim of the legal bindingness of a rule, the rule becomes legally binding on the former state. The "sound of silence" binds the state which should have reacted. As the Commentaries are defined as being legally non-binding (as confirmed by the OECD Convention, the Rules of Procedure and the Recommendation), invoking acquiescence will only be valid if there is hard evidence in the form of counter-proof that the Commentaries are binding. "Silence means consent" only makes sense in cases where a legal claim is made. This position is not easy to defend, however, in light of the legal and factual circumstances, especially as no state will claim that acquiescence in the context of the Commentaries is binding on another state. As to estoppel, this is a basic rule of decency: if a state is in for a penny, it is in for a pound and it cannot withdraw from its commitment if State B has based its conduct on that commitment. Nicaragua, for example, was precluded from challenging the arbitral award which it had, by express declaration and conduct, recognized as valid. I believe estoppel is not helpful in the case of the Commentaries. First, for estoppel, the act must be clear and unambiguous as well as unconditional and authorized, and the second state must have relied in good faith upon that act to its own detriment or the first states advantage. In my view, these conditions have not been met, as there is simply no act or reliance on that act. Second, there is an issue of evidence: as we do not know what happened during the treaty negotiations, due to their secret nature and the non-publication of the travaux prparatoires, it is a mere assumption that the Commentaries were part of the negotiations. Even if estoppel is accepted, only the executive will be bound, as explained above, and not the state itself. Most importantly, the conduct giving rise to the invocation of acquiescence or estoppel must have legal significance in the social playing field. Even if a government did not express dissent to the Commentaries during treaty negotiations, this does not provide a reason why this should have a legal effect where the states have officially proclaimed not to be bound and have acted accordingly. The similarity to the Temple case is weak, as I have explained in my earlier article on this subject. [199] Since Thailand acted as if the facts of the case represented the legal situation (the Temple belonging to Cambodia), Thailand was precluded from taking the position that the Temple did not belong to Cambodia. Firstly, the Temple

http://online.ibfd.org/highlight/collections/lsco/html/lsco_c06.html?q=soft+hard+non...

14/08/2013

Beyond Legal Bindingness

Pgina 13 de 17

case is a boundary case, and therefore directly connected to war and peace and world stability. Boundary regimes are special regimes: borders are left intact even after expiry of a border treaty, irrespective of whether the states expressed a will to let the border treaty expire. Secondly, even if similar principles apply to both situations, the Temple case also differs from the case of the Commentaries in that the parallel is missing. In the Temple case, a boundary treaty was concluded in 1904 according to which the Temple of Preah Vihear would be on Thai territory. In 1907, however, a new map mistakenly showed the temple to be on Cambodian territory. This map was published in 1908. More than a quarter of a century later, the Thai government discovered the mistake, but did not make any representation. It also remained silent during the negotiations leading up to the 1937 treaty, in which the existing borders were expressly confirmed, as well as on the occasion of the treaty of 1946. Thailand even presented maps to international commissions showing the Temple to be on the Cambodian side of the border. More than 40 years after the 1904 treaty, Thailand stationed four keepers at the temple and 50 years later, in 1954, Thailand considered itself entitled to station military troops in the Temple. Not surprisingly, the International Court of Justice took the position that in these circumstances, Thailand had forfeited its right to invoke the inaccuracy of a map which had been drawn up at Thailands request and in respect of which Thailand had never claimed exceptions, not even following the discovery of the mistake in 1934. In such circumstances, the prevailing view is that bindingness cannot be thrust upon states whose silence coincides with their expressed will recorded in official historic instruments and their subsequent acts. It should also be borne in mind that acquiescence and estoppel play a role in cases where the evidence is unclear and equivocal. In those cases, acquiescence and estoppel may serve as interpretational aids in support of the facts and the legal instruments. However, estoppel and acquiescence must be used with caution and only in situations where the legal documents and behaviour are not equivocal in nature. Even though there can be no doubt that good faith, estoppel and acquiescence may cause the Commentaries (as well as other MOUs) to be legally binding, there is no actual evidence nor any argumentation which can be considered more than just plausible in light of the social and linguistic environment - which might indicate otherwise - that the Commentaries are legally binding. In my view, the position defended by Engelen is an interesting theoretical possibility but it ignores the realities and details of the case considered.

7. The domestic plane

What if the Commentaries are binding on the states despite the foregoing? Would the Commentaries be binding on the taxpayers and the courts in the domestic legal order? From a Dutch perspective: according to the Dutch Constitution, validity of international law in the Dutch legal order and bindingness on the Dutch citizen are two different things. Validity of international law is based on unwritten constitutional law and is not expressed in any provision of the Dutch Constitution. Validity means no more than that an internationally binding rule is part of the domestic system of rules. If the Commentaries were binding on the Netherlands, they would be valid in the Dutch domestic legal order. Validity, however, does not mean that the rule can be enforced against the citizens, as citizens will be bound only if additional conditions are met. These conditions are specified in Art. 93 of the Constitution, which reads as follows: "Treaty provisions and decrees of international organizations which can be binding on every person in terms of their contents shall only be binding after they have been published." This article originally only served to protect citizens against direct application of international law, but - by later interpretation - also prevented citizens from invoking international law unless the applicable conditions were met. The OECD Commentaries have not been published in the manner prescribed by Dutch law (as based on Art. 95 of the Constitution) and for that reason alone cannot be considered to be binding upon the taxpayers. The Dutch Supreme Court applied a similar reasoning in the German Mutual Agreement case. [200] Moreover, Art. 93 of the Constitution limits the scope of bindingness to treaty provisions and decrees of international organizations. The Commentaries do not belong to either category, and the history of the Dutch Constitution explicitly excludes other sources of international law from the scope of Art. 93, such as international customary law or jus cogens. Only a treaty or a decision by an international organization can have a binding effect on citizens. This also confirms that the Commentaries are not binding. The Commentaries therefore do not have effect in the Dutch legal order by force of the Constitution. Is there any other way in which the Commentaries might percolate into the Dutch legal order? In the field of human rights, where judgements of the European Court of Human Rights bind the states only in the case adjudicated and not in any subsequent cases, the Dutch Supreme Court nevertheless incorporates these judgements in later cases and takes the European Courts judgements as leading instruments in the interpretation of the European Convention on Human Rights. The judgements are more or less "integrated" into the European Convention, and the European Courts interpretation is awarded a kind of erga omnes effect. The Supreme Court has never bestowed any such interpretational status on the Commentaries, and has never expressed the opinion that the Commentaries should be read as an integral part of the tax treaties. Thus, the prevailing view is that the Commentaries do not have effect on the domestic plane, even if they were to create an obligation at the international level (which they do not). [201]

http://online.ibfd.org/highlight/collections/lsco/html/lsco_c06.html?q=soft+hard+non...

14/08/2013

Beyond Legal Bindingness

Pgina 14 de 17

8. Conclusion