Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Moralization of Genocide in Canada

Uploaded by

paganmediathatbitesCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Moralization of Genocide in Canada

Uploaded by

paganmediathatbitesCopyright:

Available Formats

THE MORALIZATION OF GENOCIDE IN CANADA Christopher Powell, Ph.D.

Prairie Perspectives on Indian Residential Schools, Truth, and Reconciliation The Forks, Winnipeg, MB, Thursday 17 June 2010 Opening Statement I thank the Cree and Anishnabe peoples for hosting us on this their land, and I dedicate my talk to them and to the other First Peoples of this continent as they struggle for self-determination. I hope that what I have to say is useful for that struggle. Now, I have changed the focus of my talk somewhat from what is indicated in the abstract in your program. When I sat down to write these comments, it came to me that, as a genocide scholar, it could be worthwhile for me to explain why I consider the implementation and administration Indian Residential School system to have been an act of genocide, before I explain how it is that genocides can seem moral to those who help commit them. I hope Im not belabouring the obvious. But my sense is that for many Indigenous people, the applicability of the term genocide is self-evident and common sense, but that for most White Canadians, its far from apparent. Id like to talk about two word: genocide, and morality. Usually these words dont go together; in fact, usually, they are opposites. But sociologists study morality, not in terms of what people ideally ought to do, but what they actually do, what they say they believe to be moral and what they do when they consider themselves to be acting morally. In these terms, morality is a social institution like law, or tradition, or custom, or any other set of rules. And in these terms, genocide can be made moral it can be moralized. That is, genocide can become something that people believe they have a moral right and a moral obligation to carry out. Most settler Canadians believe that Canada is a moral country, so it is unthinkable that Canada should be culpable for genocide. But I argue that it is precisely because Canada is a moral country that genocide could happen here in the way that it has. So the first part of my talk will address the concept of genocide, while the second part of my talk will focus on the moralization of genocide. Part 1 - Genocide For most people, the Nazi holocaust, and specifically the Nazi extermination of European Jews, comes to mind as the prototypical example of genocide. And its true that horror at the concentration camps and the gas chambers helped to mobilize the political will behind the passing of the 1948 United Nations Genocide Convention. But the genesis of the concept of genocide, as something that ought to be a crime, goes further back then the Jewish holocaust or the Nazis themselves.

The Moralization of Genocide in Canada

Page 2

During the First World War, the armed forces of the Ottoman Empire, led by Turkish nationalists, systematically murdered or expelled nearly all of the Empires ethnic Armenians. An estimated one million Armenians were killed, not only by direct violence, but also from being force-marched entire villages, men, women, children, elders through desertous mountain passes, where many died of from hunger and thirst and exposure to cold, on their way to the borders of the Empire (see, e.g.Dadrian 1997; Bloxham 2007). This event became news around the world, and and in the small town of Bezvodny in Imperial Russia, a young Jewish man named Raphael Lemkin, learning of destruction of the Armenians, began the emotional and intellectual journal that would eventually lead him to coin the term genocide (Elder 2005). In 1933, Lemkin submitted to the Legal Council of the League of Nations in Madrid a proposal to criminalize two new acts: barbarity, defined as action against the life, bodily integrity, liberty, dignity, or economic existence of a person, if taken out of hatred towards a racial, religious, or social collectivity, or with a view to the extermination thereof; and vandalism, defined as destruction of cultural or artistic works for the same reason (Lemkin 1947). However, his proposal did not succeed. I mention this earlier effort because it shows how Lemkin saw a connection between cultural destruction and physical destruction. These two meanings come together in Lemkins conception of the term genocide, which he proposed in the 1944 book Axis Rule in Occupied Europe. I will quote him at some length: By genocide we mean the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group. [] Generally speaking, genocide does not necessarily mean the immediate destruction of a nation, except when accomplished by mass killings of all members of a nation. It is intended rather to signify a coordinated plan of different actions aiming at the destruction of essential foundations of the life of national groups, with the aim of annihilating the groups themselves. The objectives of such a plan would be disintegration of the political and social institutions, of culture, language, national feelings, religion, and the economic existence of national groups, and the destruction of the personal security, liberty, health, dignity, and even the lives of the individuals belonging to such groups. Genocide is directed against the national group as an entity, and the actions involved are directed against individuals, not in their individual capacity, but as members of the national group. (Lemkin 1944: 79) Mass killing is not intrinsic to genocide, but social and political and cultural disintegration are. This is the first published use of the term genocide. Most of the book in which it appears does not discuss genocide, but colonialism specially, German colonialism in Eastern Europe. In unpublished notes that Lemkin wrote for his planned Encyclopedia of Genocide, which tragically he never finished, Lemkin examined the history of genocide in the colonization of the Americas (McDonnell and Moses 2005). Although he focused almost exclusively on the depredations of the Spanish as recorded by Bartholome de las Casas, its clear that Lemkin considered the destruction of a culture by a colonizing power to be genocide.

Christopher Powell, The Forks, Winnipeg, Thursday 17 June 2010

The Moralization of Genocide in Canada The 1948 Genocide Convention presents a narrower conception of genocide, but even this definition is broader than simply mass killing:

Page 3

In the present Convention, genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial, or religious group, as such: (a) Killing members of the group; (b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group; (c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part; (d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group; (e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group Forcibly transferring children out of a group, in order to destroy the group as such, counts as genocide. In Canada, The federal government wanted Aboriginal people to assimilate into Canadian society. According to Duncan Campbell Scott, the principal architect of Indian residential school policy, Our objective is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic, and there is no Indian question and no Indian Department. ... I want to get rid of the Indian problem (Funk-Unrau and Snyder 2007: 285) In the relatively narrow terms of the Convention, then, the history of the Indian Residential School system in Canada is a history of genocide, and the Government of Canada is culpable for that genocide. And in the fuller conception of genocide elaborated by Lemkin, the residential school system was only one component of a coordinated plan of different actions that included legislated attacks on Indigenous political, economic, religious, and family institutions made with the aim of dissolving the many First Peoples and incorporating the remaining individuals, severed from their culture, into White settler society. Part 2 - Morality In 1940, in the small rural community of Wittlich, Germany, a 12 year old boy named Alfonz Heck watched as the Gestapo arrested and took away his best friend, Heinz, along with all of the Jews in his village. Writing about the event many years later, Alfonz revealed that at that moment he did not say to himself, How terrible they are arresting Jews. Having absorbed knowledge about the Jewish menace, he said, what a misfortune Heinz is Jewish. As an adult he recalled, I accepted deportation as just (Koonz 2003: 5). In her remarkable book, The Nazi Conscience, historian Claudia Koonz has documented the range of ways in which the National Socialist German Workers party cultivated a public morality. In schools and universities, in youth programs and family education seminars, in newspapers and civil society organizations, the Nazis cultivated an idealistic and self-sacrificing sense of love for and duty towards the German Volk. Scientists set to work formulating strict Christopher Powell, The Forks, Winnipeg, Thursday 17 June 2010

The Moralization of Genocide in Canada

Page 4

racial categorizations, and although they met with persistent failure, the idea of the Volk as a natural, biological unit of human community gained widespread legitimacy in Germany through discourses that mentioned Jews only tangentially and usually in moderated tones. Through a lively and participatory public discourse, the Nazis established a conceptual framework that naturalized Jewish exclusion from citizenship and from moral obligation, by situating that exclusion within a larger framework that defined positive ideals and aspirations for individuals and the nation. Through these measures, the Nazis created a cultural climate in which individual Germans could be persuaded that murder and even genocide were moral obligations. Sociologists who study morality do so in terms of what people actually do that is, what people say they believe to be moral and what they do when they claim to be acting morally. In this sense, morality is a social institution, like law or custom. The French sociologist Emile Durkheim observed that morality in Western societies tends to have several characteristics: 1. morality is authoritative one obeys moral precepts for their own sake, not as a means to some personal end; 2. morality defines some good that is desirable and desired; and 3. morality is sanctioned by widespread public opinion (Durkheim 2002: 29, 33-35) Crucially, Durkheim understood morality as an objective social fact (Durkheim 1982, 1984) and, therefore, as something that people encounter as coming from outside themselves. So, if a person follows an obligation that they perceive as coming, not just from another person in particular, but from society in general, and that obligation is authoritative, desirable, and publicly approved of, then they will experience that obligation as a moral one. Precisely these conditions obtained in the Third Reich, and the testimony of people like Adolph Eichmann, that is, ordinary bureaucrats and soldiers who participated in genocide (see for instance Arendt 1994), shows that they experienced the extermination of an entire people as a moral duty, personally unpleasant, but necessary in the service of a higher purpose in this case, the purification of the Aryan race, a project that was held to benefit not only the German nation but the human species as such. Did a comparable sense of higher moral purpose animate the process of genocide in Canada? The findings of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples suggests that it did, at least as regards the Indian Residential Schools. Chapter 10 of the Commissions Report describes the rationale of the schools as having been based on the perception of Indian cultures as savage, backward, and unable to survive in the European modernity that the settler society was of necessity building in the lands it had appropriated (Dussault et al. 1996). Moreover, adult Indians were perceived not only as incapable of adaptation but an obstacle to it; children needed to be separated from their parents and from all contact with their culture if they were to have any hope of being civilized. Only in the children could hope for the future reside, for only children could undergo the transformation from the natural condition to that of civilization. Aboriginal children had to be rescued from their evil surroundings, isolated from parents, family and community, and kept constantly within the circle of civilized conditions. There, through a purposeful course of instruction the Christopher Powell, The Forks, Winnipeg, Thursday 17 June 2010

The Moralization of Genocide in Canada savage child would surely be re-made into the civilized adult (Dussault et al. 1996).

Page 5

According to this rationale, workers in the Indian Residential School system could understand their actions, painful as they were in the short term, as ultimately beneficial for the children involved, for Aboriginal people, and for the Canadian nation. Of course, this does not explain sexual abuse; nor does it explain the terrible death rate of children in the schools from disease and dangerous working conditions. Nor does it obviate the personal hatred that some school personnel displayed towards their young charges. But this notion of the IRS system as benefiting the Indians by civilizing them provided a framework in relation to which specific acts of violence could register as necessary to the task at hand. In this context, only a very few instances of violence might appear unjustified or excessive, compared with the great weight of moral necessity of the project as a whole. This moralizing framework harmonized with dominant narratives about the superiority of Western civilization, on which the project of state-building in Canada has based its legitimacy in no small part. Genocide was an authoritative obligation pursued for a higher goal, approved of by the public opinion of White settler culture. As experienced by its perpetrators, genocide in Canada was moral. Or we today who do not approve of it can say that it was moralized: it was made into a moral obligation. For that to have happened, the moralization of genocide must have connected up with much broader elements of Canadian settler culture. And I will say in conclusion that I dont think that White settler society has begun to face up to the significance of that fact, and to what it says about the project of building Canada as a nation.

Christopher Powell, Ph.D., is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Sociology at the University of Manitoba. He is the author of What do genocides kill? A relational conception of genocide in the Journal of Genocide Studies (2007) and of The Wound at the Heart of the World, in Evoking Genocide: Scholars and Activists Describe the Works that Shaped Their Lives (Adam Jones, ed., 2009.) His book Civilization and Genocide is forthcoming in 2011 from McGill-Queens University Press. Contact Info: tel: (204) 474-8150 / fax: (204) 261-1216 email: chris_powell@umanitoba.ca http://home.cc.umanitoba.ca/~powellc0

Christopher Powell, The Forks, Winnipeg, Thursday 17 June 2010

The Moralization of Genocide in Canada Works Cited

Page 6

Arendt, Hannah. 1994. Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil. Revised and Enlarged Edition ed. New York: Penguin Books. Bloxham, Donald. 2007. The Great Game of Genocide: Imperialism, Nationalism, and the Destruction of the Ottoman Armenians. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Dadrian, Vahakn N. 1997. The History of the Armenian Genocide: Ethnic Conflict from the Balkans to Anatolia to the Caucasus. Third, Revised ed. Providence: Berghahn Book. Durkheim, Emile. 1982. The Rules of Sociological Method. In Durkheim: The Rules of Sociological Method and Selected Texts on Sociology and its Method, edited by S. Lukes. New York: The Free Press. . 1984. The Division of Labour in Society. New York: The Free Press. . 2002. Moral Education. Translated by E. K. Wilson and H. Schnurer. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications. Original edition, 1961. Dussault, Ren, Georges Erasmus, Paul I. A. H. Chartrand, J. Peter Meekison, Viola Rosbinson, Mary Sillett, and Bertha Wilson. 2010. Royal Commission Report on Aboriginal Peoples. Government of Canada 1996 [cited 15 June 2010]. Available from http://www.aincinac.gc.ca/ap/rrc-eng.asp. Elder, Tanya. 2005. What you see before your eyes: documenting Raphael Lemkin's life by exploring his archival Papers, 1900-1959. Journal of Genocide Research 7 (4):469-499. Funk-Unrau, Neil, and Anna Snyder. 2007. Indian Residential School Survivors and StateDesigned ADR: A Strategy for Co-Optation? Conflict Resolution Quarterly 24 (3):285304. Koonz, Claudia. 2003. The Nazi Conscience. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press. Lemkin, Raphael. 1944. Axis rule in occupied Europe : laws of occupation, analysis of government, proposals for redress, Publication of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Division of International Law, Washington. Washington: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace Division of International Law. . 1947. Genocide as a Crime Under International Law. American Journal of International Law 41. McDonnell, Michael A., and A. Dirk Moses. 2005. Raphael Lemkin as historian of genocide in the Americas. Journal of Genocide Research 7 (4):501-529.

Christopher Powell, The Forks, Winnipeg, Thursday 17 June 2010

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- German Colonial Rule in NamibiaDocument405 pagesGerman Colonial Rule in Namibiagrifmejl100% (1)

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- Position Paper SenegalDocument2 pagesPosition Paper SenegalNicoleNo ratings yet

- Hotel Rwanda analysis of cultural, political, economic aspectsDocument3 pagesHotel Rwanda analysis of cultural, political, economic aspectsJoey WhelihanNo ratings yet

- Hitler Analysis SpeechDocument5 pagesHitler Analysis Speechapi-356941649100% (1)

- What Is Racism - PK Subban & Michel Therrien PDFDocument2 pagesWhat Is Racism - PK Subban & Michel Therrien PDFpaganmediathatbitesNo ratings yet

- The Real Deal On First Nations Trust Funds in Canada Held by The Federal GovernmentDocument2 pagesThe Real Deal On First Nations Trust Funds in Canada Held by The Federal Governmentpaganmediathatbites100% (2)

- Report by DR Peter Bryce in 1922 Indian Resindentia Schools in CanadaDocument17 pagesReport by DR Peter Bryce in 1922 Indian Resindentia Schools in Canadapaganmediathatbites100% (1)

- Cloyne Report Intro - Signature of Who Headed Commission in IrelandDocument4 pagesCloyne Report Intro - Signature of Who Headed Commission in IrelandpaganmediathatbitesNo ratings yet

- Outlawing The Potlatch - Outlawing Indians - A Contemporary Analysis of Canada & USA Ethnic CleansingDocument5 pagesOutlawing The Potlatch - Outlawing Indians - A Contemporary Analysis of Canada & USA Ethnic CleansingpaganmediathatbitesNo ratings yet

- The Raphoe Report - A Crtical Review of Bishops in Irland Into Child AbuseDocument34 pagesThe Raphoe Report - A Crtical Review of Bishops in Irland Into Child AbusepaganmediathatbitesNo ratings yet

- Declaration of CommitmentDocument2 pagesDeclaration of CommitmentpaganmediathatbitesNo ratings yet

- Canada's Goverment Apology To First Nations - Bears Witness As Evidence of The TruthDocument2 pagesCanada's Goverment Apology To First Nations - Bears Witness As Evidence of The TruthpaganmediathatbitesNo ratings yet

- Cloyne - Further Portions 2011Document57 pagesCloyne - Further Portions 2011paganmediathatbitesNo ratings yet

- Executive Summary of Judge Ryan Report Ireland 2009 - Church Child AbuseDocument27 pagesExecutive Summary of Judge Ryan Report Ireland 2009 - Church Child AbusepaganmediathatbitesNo ratings yet

- Cloyne Report: Allegations and Suspicions of Child Sexual Abuse Against Clerics (Dublin, Ireland - 2011)Document421 pagesCloyne Report: Allegations and Suspicions of Child Sexual Abuse Against Clerics (Dublin, Ireland - 2011)Vatican Crimes ExposedNo ratings yet

- Ken Bear Chief Public Statement Regarding Kevin AnnettDocument1 pageKen Bear Chief Public Statement Regarding Kevin AnnettpaganmediathatbitesNo ratings yet

- Vatican 1984 Intention of Cover Up Letter EvidenceDocument3 pagesVatican 1984 Intention of Cover Up Letter EvidencepaganmediathatbitesNo ratings yet

- PublicstatementofroycewhitecalfrekevinannettDocument2 pagesPublicstatementofroycewhitecalfrekevinannettpaganmediathatbitesNo ratings yet

- Nell Cole Withdraw Support of Kevin Annett - Public StatementDocument3 pagesNell Cole Withdraw Support of Kevin Annett - Public StatementpaganmediathatbitesNo ratings yet

- Resschool Sep2898coj - HtmlpublicnoticeregardingkevinannetfromcircleofjusticeDocument4 pagesResschool Sep2898coj - HtmlpublicnoticeregardingkevinannetfromcircleofjusticepaganmediathatbitesNo ratings yet

- Roycs Whitecalf Public Letter Released Regarding Kevin Annett and Nell ColeDocument5 pagesRoycs Whitecalf Public Letter Released Regarding Kevin Annett and Nell ColepaganmediathatbitesNo ratings yet

- WWW - United Church - Ca Aboriginal Schools Statements AnnettDocument9 pagesWWW - United Church - Ca Aboriginal Schools Statements AnnettpaganmediathatbitesNo ratings yet

- WWW - Bc.united Church - Ca Content Formal Hearing Panel DecisionDocument27 pagesWWW - Bc.united Church - Ca Content Formal Hearing Panel DecisionpaganmediathatbitesNo ratings yet

- Squ Amish Nation Press Release An NettDocument2 pagesSqu Amish Nation Press Release An NettpaganmediathatbitesNo ratings yet

- WWW - Courts.gov - Bc.ca JDB TXT SC 08-00-2008BCSC0054err1Document6 pagesWWW - Courts.gov - Bc.ca JDB TXT SC 08-00-2008BCSC0054err1paganmediathatbites100% (1)

- No Court Case Was Filed On July 4, 2012Document3 pagesNo Court Case Was Filed On July 4, 2012paganmediathatbitesNo ratings yet

- Ho Me Bcjustice Co Urts' Cases Land & Buildings Commerce Wrongs & Rights Drugs Finally Supreme Court of CanadaDocument8 pagesHo Me Bcjustice Co Urts' Cases Land & Buildings Commerce Wrongs & Rights Drugs Finally Supreme Court of CanadapaganmediathatbitesNo ratings yet

- Aisha Chepkemoi Student ID 11652207Document4 pagesAisha Chepkemoi Student ID 11652207LeilaNo ratings yet

- Anne Frank Act 2 QuestionsDocument4 pagesAnne Frank Act 2 Questionsjohn_986589364100% (1)

- Lenzman ShoahDocument1 pageLenzman ShoahV_KanoNo ratings yet

- Pil SchindlerDocument1 pagePil SchindlerMrc DgmoNo ratings yet

- 1915-12-8 I-The Man From ConstantinopleDocument8 pages1915-12-8 I-The Man From ConstantinoplewhitemaleandproudNo ratings yet

- Revisione Etica How Beta Odap Ended Up in Our Dishes Thanks To Nazis and CIADocument22 pagesRevisione Etica How Beta Odap Ended Up in Our Dishes Thanks To Nazis and CIADressedinblack DibbyNo ratings yet

- Exploring The Therapeutic Effects of Testimonies in Yolande Mukagasana's Not My Time To Die and Scholastique Mukasonga's CockroachesDocument20 pagesExploring The Therapeutic Effects of Testimonies in Yolande Mukagasana's Not My Time To Die and Scholastique Mukasonga's CockroachesIjahss JournalNo ratings yet

- Nazi LanguageDocument503 pagesNazi LanguageRBlake767% (3)

- Beyond Courage Teachers' GuideDocument2 pagesBeyond Courage Teachers' GuideCandlewick PressNo ratings yet

- Thesis Statement Rwanda GenocideDocument7 pagesThesis Statement Rwanda Genocidetarahardinhuntsville100% (2)

- Holocaust IntroDocument2 pagesHolocaust Introapi-283894138No ratings yet

- CV: Lovro Kralj's Academic and Professional ExperienceDocument5 pagesCV: Lovro Kralj's Academic and Professional ExperienceLovro KraljNo ratings yet

- Genocide 2Document32 pagesGenocide 2Tien-Tyn LeNo ratings yet

- Red Book of Westmarch The SilmarillionDocument1 pageRed Book of Westmarch The Silmarillionmakheabictichiou3829No ratings yet

- Names 2Document87 pagesNames 2api-259758224No ratings yet

- Critical Thinking Primary ConceptsDocument20 pagesCritical Thinking Primary ConceptsjamesdigNo ratings yet

- "Schindler's List" Is Not "Shoah": The Second Commandment, Popular Modernism, and Public MemoryDocument26 pages"Schindler's List" Is Not "Shoah": The Second Commandment, Popular Modernism, and Public Memoryjohn langbertNo ratings yet

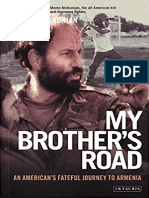

- My Brothers Road by Melkonian, Markar Seta Melkonian Z Lib OrgDocument343 pagesMy Brothers Road by Melkonian, Markar Seta Melkonian Z Lib Orghappy doge channelNo ratings yet

- Simon Wiesenthal's LiesDocument6 pagesSimon Wiesenthal's LiesHuckelberry0% (1)

- 24x24 AvenzaBasemap TolowaDunesDocument1 page24x24 AvenzaBasemap TolowaDunesMonie DNo ratings yet

- His AssignmentDocument6 pagesHis AssignmentCAPTAIN PRICENo ratings yet

- GenEd (Feb 6, 2023)Document36 pagesGenEd (Feb 6, 2023)Anne GonzalesNo ratings yet

- On The Centenary of The Greek GenocideDocument14 pagesOn The Centenary of The Greek GenocideVladislav B. Sotirovic100% (2)

- Crucified KosovoDocument17 pagesCrucified KosovoVladislav B. SotirovicNo ratings yet

- KM Srebrenica 8 May 2017Document32 pagesKM Srebrenica 8 May 2017MarijaNo ratings yet

- Holocaust PDocument51 pagesHolocaust PSA TiagoNo ratings yet