Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Why India Needs A National Nutrition Strategy

Uploaded by

lawrencehaddadOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Why India Needs A National Nutrition Strategy

Uploaded by

lawrencehaddadCopyright:

Available Formats

Why India Needs a National Nutrition Strategy Lawrence Haddad Institute of Development Studies, UK l.haddad@ids.ac.

uk August 31, 2011 Undernutrition in India remains at high levels despite rapid economic growth. If undernutrition reduction is to be accelerated, the multiple opportunities for--and challenges to--improving nutrition status demand a nutrition strategy backed by strong leadership. Introduction Over the last 15 years India has posted unprecedented economic growth rates. The IMF reports an average real GDP growth rate of nearly 6 percent in the 1990s and of 8 percent in 2000-2010 (1). This progress in economic growth has not driven corresponding reductions in undernutrition reduction (2). Undernutrition in early life is responsible for 35 percent of under 5 child deaths, reduces cognitive attainment, substantially increases the likelihood of being poor and has a close link with illness or death during pregnancy and lactation (3). The nationally representative National Family Health Survey, the Governments most authoritative source of nutrition status statistics, shows that 43 percent of children under 5 were underweight for age in 1998-99. Using a later round of the survey, by 2005-6 that percentage had dropped to 40 percent (4). At that rate of progress India will reach its Millennium Development Goal (MDG) nutrition indicator by 2043 instead of 2015 (5). China has already met its goal, halving its 1990 rate of underweight a few years ago and the MDG will most likely be met for Brazil by 2015 (6). Why are high levels of undernutrition so persistent? There is likely no single answer. The possibilities fall into 4 categories: Indias growth is not pro-poor enough; no matter how pro-poor Indias growth is, the underlying environment for undernutrition reduction is just too challenging; nutrition interventions are not effective; and the governance of undernutrition is not strong enough. What does the evidence say and what are the implications for action? Economic growth is poverty reducing but not nutrition improving The poverty rate has declined at a faster rate post-1991 than pre-1991: 0.5 percentage points per year during 1958-91 compared to 0.8 percentage points per year during 19912006 (7). This compares well against the more lauded performance of China. Over the 1981-2005 period Chinas poverty rates declined from 40 percent to 29 percent while Indias declined from 60 percent to 42 percent (both about a 30 percent proportionate decline). The ability of Indias economic growth to reduce poverty is in line with other countries (8) and has been constant over the past 15 years (7) which is consistent with the evidence that income inequality has remained reasonably stable (it has increased by 12% between 1983 and 2005) (9). So economic growth is reducing poverty at a good rate but it is not reducing undernutrition. Why not? The enabling environment for undernutrition reduction is not strong 1

Might Indias economic growth be preventing from reducing undernutrition because of a weak enabling environment for nutrition improvements? The UNICEF model of undernutrition (10) articulates three levels of determinants: fundamental, underlying and immediate. Economic growth and governance (which will be reviewed later) are key fundamental drivers. Underlying factors include agriculture and food security, womens power in decision making, care to infants and the sanitation and health context. Immediate determinants include diet and infection. This section focuses on underlying determinants and the following focuses on more immediate factors. Agriculture: In most contexts we would expect agricultural growth to have large impacts on the nutrition status of children. Agricultural growth is typically more poverty reducing than other sources of growth (11). Agricultural growth also improves food availability. But agricultural growth in India does not seem to have an impact on infant undernutrition (12). It is vital to unpack this apparent disconnect. There are a number of success stories from the region and elsewhere that can point the way towards making agriculture more nutrition sensitive, ranging from homestead gardening, livestock and dairy interventions, and fruit and vegetable productivity to the biofortification of staple crops with Iron, Zinc and Vitamin A (13). The national agricultural system needs to be supported and incentivised to innovate for improved nutrition. Food Security Programmes: Food security is also promoted by a number of Government programmes: the Targeted Public Distribution System or TPDS, the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA) and the Midday Meal Scheme. An evaluation of the TPDS by the Indian Planning Commission in 2005 concluded that the majority of subsidized food does not reach its intended recipients (14). Some have proposed cash transfers programmes (15) to improve transparency and the accountability of efforts to improve nutrition status--a theme we will return to later in the paper. In terms of employment guarantee programmes, the two high quality impact studies show contrasting impacts on household expenditures: one positive and one negative (16). The Midday Meals Scheme covers 139 million children in primary school. The most rigorous evaluation finds it to have a positive and statistically significant impact on stunting and underweight rates of 4-5 year olds (17). This is a positive story but the Scheme does not affect infants in the 2-3 year age group who are most vulnerable to nutrition insults. Womens Status: Discrimination against women in South Asia has long been thought to be one of the key drivers of infant undernutrition in the region (18). Multi-country analysis shows that womens low status relative to men is responsible for a significant, although not a majority, share of the difference in infant undernutrition rates between South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa (19). Discrimination against women is an important part of the story and efforts to empower womeninside and outside of the nutrition sphere need to be redoubled. Health: Indias health system is ranked significantly below those of Bangladesh and Sri Lanka (20). Spending on the public health system is low (less than 1 percent of GDP) and over 80 percent of health expenditures are out of pocket. There have been recent calls on the Government to increase public sector spending to 6 percent of GDP by 2020 and to adopt a wide range of actions needed to strengthen the system (21).

Water and Sanitation: Rates of access to improved drinking water are low but in line with many other countries at similar levels of economic development. Access to improved sanitation is particularly poor. According to WHO, 640 million Indians still practice open defecation, accounting for 56 percent of the worlds total (22). We know that infection rates are powerfully associated with unsanitary conditions. Community Led Total Sanitation has proven to be a cost-effective way of scaling up latrine use in rural communities in Orissa (23) and its promotion merits consideration. Caste: Social discrimination against certain castes and groups is a powerful exclusionary factor in many Indian states. Cross section data show how low caste is associated with poor access to services and therefore poor nutrition and health outcomes, even when controlling for education and welfare levels (24). Longitudinal analysis from Andhra Pradesh finds being from a scheduled caste or a backward tribe substantially increases the probability of a child being stunted--and persistently so (25). Efforts to reduce such discrimination will greatly enhance the environment for undernutrition reduction. So the underlying context is not strong for economic growth to generate undernutrition reduction: agricultural growth has little effect, womens status is difficult to change quickly, the health system will take time to strengthen, the sanitation environment is extraordinarily undermining of nutrition status and social exclusion is an important and persistent constraint to improved nutrition. Can Indias nutrition interventions overcome these barriers? Nutrition interventions could do more The Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) programme is the main nutrition related programme. The latest impact evaluation (26) finds that it has a positive and significant impact of six percent on the under three stunting rate, yielding a 3.75 fold net return on investment. This is low compared to community based nutrition promotion efforts elsewhere which attain ratios of 12:1 (27). The evaluation shows the effects of ICDS are weaker for under 2s, for girls, and for those with the most severe stunting and that the centres are not always placed where they are most needed. This suggests scope for ICDS to become more efficient in reducing infant stunting. The consensus on what to do includes: allowing different districts to adapt it to circumstances, employing more nutrition centre workers so that each age group (0-2 and 3-6 year olds) can receive tailored attention, reaching out to excluded castes, improving the quality of physical conditions and the accountability of ICDS centres to the people they serve (28). In terms of other essential nutrition interventions, coverage is low (29). For example, infant and young child feeding interventions cover only 25 percent of vulnerable children and vitamin A supplementation covers 30-40 percent of the vulnerable population, depending on the State. The new Accredited Social Health Activist programme pays community health workers to improve these coverage rates and improve the quality of service delivery to improve young child nutrition. So far no evaluations are available to assess its impact on nutrition status, but other evaluations (30) suggest stronger recruitment and support systems need to be put in place to assist these crucial activists in the fight against undernutrition. The governance of nutrition needs strengthening

Given the multiple opportunities for investing in nutrition and the multiple ways that nutrition status can be undone, it is vital that there is a nutrition strategy backed by strong leadership. Brazil has done this successfully, leading to dramatic declines in hunger and child undernutrition rates (6). The Government is not well supported to do this by available information and is not sufficiently pushed to act strategically. First, nutrition data are collected every 5-6 years. This is too infrequent to track changes and respond to events. Second, because there are so many moving parts in any nutrition strategy the Government needs to use nutrition diagnostic tools to prioritise and sequence action to improve child growth, in the way it does for economic growth. Third, this variation in contexts is also matched by variance in nutrition status. There are many bright spots in the fight against malnutrition (e.g. the recent Karnataka Nutrition Mission) but the incentives to analyse and learn from them are weak. This lack of data and strategic analysis also diminishes the effectiveness of Indian civil society to mobilise around nutrition. For example, the Right to Food Campaigns push for a National Food Security Act makes important demands, but even if some of them are met, they will need transparent monitoring of resource flows to promote accountability of all stakeholders. The research community in India has a vital role to play in helping to meet these needs: to design new ways of monitoring nutrition status more frequently, to develop new ways of diagnosing contexts in terms of priorities for nutrition action, to analyse success and failure in multisectoral coordination, to promote learning within and across states on what works in nutrition and why, and to test and evaluate transparency and accountability mechanisms for nutrition. Conclusion: a nutrition strategy is needed At current rates India will meet its MDG target by 2043 rather than 2015. Economic growth is poverty reducing and this should help undernutrition reduction in the long run. But the current environment is not as supportive to nutrition as it could be. Action is needed to: make agriculture more pro-nutrition by focusing it more on what people living in poverty grow, eat, and need nutritionally experiment with cash-based alternatives to the Targeted Public Distribution System promote community led approaches to sanitation increase coverage of essential nutrition interventions in the context of a stronger public health system focus Integrated Child Development Services resources more on children under 2, on severe undernutrition and locate centres where they are most needed, and continue the fight against gender and social exclusion

But most importantly, India needs a national nutrition strategy with a senior leader within the Government empowered to implement that strategy. Successful implementation needs civil society to play its part, helping to shape and deliver the strategy and promoting greater transparency and accountability in the fight against undernutrition.

In the context of rapid economic growth, persistently high levels of undernutrition may seem like a curse (5) but, as this article has outlined, there are many things that can be done to lift the spell. The most important thing is the commitment to do so. References (1) (2) IMF. 2011. World Economic Outlook. Tensions from the Two-Speed Recovery: Unemployment, Commodities, and Capital Flows. April. Washington D.C. Subramanyam M. A., I. Kawachi, L. F. Berkman, and S. V. Subramanian. 2011. "Is economic growth associated with reduction in child undernutrition in India?" PLoS Medicine. 8 (3). Black, R., L. Allen, Z. Bhutta, L. Caulfield, M. de Onis, M. Ezzati, C. Mathers, J. Rivera, (for the Maternal and Child Undernutrtiion Study Group). 2008. Maternal and child undernutrition: Global and regional exposures and health consequences, Maternal and Child Undernutrition Series 1, Lancet, published online: January, 17, 2008 Government of India. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. National Family Health Survey-3 (2005-6). Nutrition in India. 2009. F. Arnold, S. Parasuraman, P. Arokiasamy and M. Kothari. Haddad, L. 2009. Lifting the Curse: Overcoming persistent undernutrition in India. Pp 1-9. In Lifting the Curse: Overcoming persistent undernutrition in India, Eds. L. Haddad and S. Zeitlyn, IDS Bulletin, Vol. 40. No. 4 Victora, C.G., Barreto, M.L., do Carmo Leal, M., Monteiro, C.A., Schmidt, M.I., Paim, J., Bastos, F., Almeida, C, Bahia, L., Travassos, C., Reichenheim, M., Barros, F. and the Lancet Brazil Series Working Group. 2011. Health conditions and health-policy innovations in Brazil: the way forward. Volume 377, Issue 9782, Pages 2042-2053 Datt, G. and M. Ravallion. 2010. Shining for the Poor Too? Economic and Political Weekly. February 13, vol. xlv no 7 Bourguignon, F. 2003. The Growth Elasticity of Poverty Reduction: Explaining Heterogeneity across countries and time periods. In: Inequality and growth: theory and policy implications. Eds. T.S. Eicher and S. J. Turnovsky. MIT Press. Sarkar S., and B.S. Mehta. 2010. Income Inequality in India: Pre- and PostReform Periods. Economic and Political Weekly. September 11, 2010. vol xlv no 37.

(3)

(4)

(5)

(6)

(7) (8)

(9)

(10) United Nations Childrens Fund (UNICEF). 1990. Strategy for Improved Nutrition of Children and Women in Developing Countries. UNICEF. New York. (11) Christiaensen, L, L. Demery, and J. Kuhl. 2010. The (Evolving) Role of Agriculture in Poverty Reduction: An Empirical Perspective. WIDER Working Paper No. 2010/36. 5

(12) Headey, D. 2011. Pro-Nutrition Economic Growth: What Is It, and How Do I Achieve It? Background paper for the conference Leveraging Agriculture for Improving Nutrition and Health, organized by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), New Delhi, February 1012, 2011. (13) Masset, E., Haddad L., Cornelius A. and Isaza-Castro J. 2011, The Effectiveness of agricultural interventions aimed at improving the nutritional status of children, DFID/3ie Systematic Review. IDS Draft working paper. (14) Government of India (GoI). 2005. Performance Evaluation of Targeted Public Distribution System (TPDS). Programme Evaluation Organisation, Planning Commission, Government of India, New Delhi. March 2005 (15) Mehrotra, S. 2010. "Communications for Debate and Research - Introducing Conditional Cash Transfers in India: A Proposal for Five CCTs". The Indian Economic Journal. 58 (2): 140. (16) Hagen-Zanker, J., A. McCord, R. Holmes, F. Booker and E. Molinari. 2011. A Systematic Review of the Impact of Employment Guarantee Schemes and Cash Transfers on the Poor. Overseas Development Institute. London. June. (17) Singh, A. 2008. Do School Meals Work? Treatment Evaluation of the Midday Meal Scheme in India. Young Lives Working Paper. Oxford University. (18) Ramalingaswami V., Jonsson U., Rohde J. 1996. The South Asian enigma. In The Progress of Nations. New York: UNICEF, pages 10-17. (19) Smith, L.C. U. Ramakrishnan, A. Ndiaye, L. Haddad, and R. Martorell. 2003. The Importance of Womens Status for Child Nutrition in Developing Countries. IFPRI Research Report 131. Washington D.C. (20) WHO. 2000. Health systems: improving performance. Geneva: WHO, 2000 (21) Reddy, K.S., V. Patel, P. Jha, V.K. Paul, A.K. Shiva Kumar and L. Dandona. 2011. Towards achievement of universal health care in India by 2020: a call to action. Lancet. Published Online. January 12. (22) WHO/UNICEF. 2010. Progress on Sanitation and Drinking-water: 2010 Update. WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply and Sanitation. Geneva. (23) Pattanayak, S K, Yang, J., Dickinson, K. L., Poulos, C., Patil, S.R., Mallick, R. K., Blitstein, J. L., Praharaj, P. 2009. IShame or subsidy revisited: social mobilization for sanitation in Orissa, India. Bull World Health Organ vol.87 no.8 Genebva Aug. (24) Thorat, S. and N. Sadana. 2009. Discrimination and Childrens Health in India. Pp 25-29. In Lifting the Curse: Overcoming persistent undernutrition in India, Eds. L. Haddad and S. Zeitlyn, IDS Bulletin, Vol. 40. No. 4 (25) Himaz, R. 2009. Persistent Stunting in Middle Childhood: The Case of Andhra Pradesh Using Longitudinal Data: pp 30-37. In Lifting the Curse: Overcoming 6

persistent undernutrition in India, Eds. L. Haddad and S. Zeitlyn, IDS Bulletin, Vol. 40. No. 4 (26) Kandpal, E. 2011. Beyond Average Treatment Effects: Distribution of Child Nutrition Outcomes and Program Placement in Indias ICDS. Forthcoming. World Development. (27) Horton, S., H. Alderman, and J. Rivera. 2008. Malnutrition and Hunger. Copenhagen Consensus Centre. Denmark. (28) Saxena N.C. and N. Srivastava. 2009. ICDS in India: Policy, Design and Delivery Issues. Pp 45-52. In Lifting the Curse: Overcoming persistent undernutrition in India, Eds. L. Haddad and S. Zeitlyn, IDS Bulletin, Vol. 40. No. 4 (29) Menon, P., K. Raabe, and A. Bhaskar. 2009. "Biological, Programmatic and Socio political Dimensions of Child Under nutrition in Three States in India". IDS Bulletin. 40 (01): 60-69. (30) Ved, R. 2011. ASHA: Which way forward? Executive Summary of Evaluation of ASHA Programmeme in Eight States (DRAFT). National Health Systems Resource Center. The Corresponding Author has the right to grant on behalf of all authors and does grant on behalf of all authors, a worldwide licence to the Publishers and its licensees in perpetuity, in all forms, formats and media (whether known now or created in the future), to i) publish, reproduce, distribute, display and store the Contribution, ii) translate the Contribution into other languages, create adaptations, reprints, include within collections and create summaries, extracts and/or, abstracts of the Contribution, iii) create any other derivative work(s) based on the Contribution, iv) to exploit all subsidiary rights in the Contribution, v) the inclusion of electronic links from the Contribution to third party material where-ever it may be located; and, vi) licence any third party to do any or all of the above. The author has completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- ETP48300-C6D2 Embedded Power User Manual PDFDocument94 pagesETP48300-C6D2 Embedded Power User Manual PDFjose benedito f. pereira100% (1)

- South Africa GNR Haddad FinalDocument39 pagesSouth Africa GNR Haddad FinallawrencehaddadNo ratings yet

- Maharashtra's Stunting Declines: What Caused Them?Document11 pagesMaharashtra's Stunting Declines: What Caused Them?lawrencehaddadNo ratings yet

- Slides From The Global Nutrition Report Dhaka Launch Nov 4, 2015Document38 pagesSlides From The Global Nutrition Report Dhaka Launch Nov 4, 2015lawrencehaddadNo ratings yet

- Haddad NY Launch of Global #NutritionReport Sept 22Document43 pagesHaddad NY Launch of Global #NutritionReport Sept 22lawrencehaddadNo ratings yet

- Smith Haddad 2014: Drivers of Stunting Declines 1970-2012Document18 pagesSmith Haddad 2014: Drivers of Stunting Declines 1970-2012lawrencehaddadNo ratings yet

- Quality of Economic GrowthDocument15 pagesQuality of Economic GrowthlawrencehaddadNo ratings yet

- We Can End MalnutritionDocument31 pagesWe Can End MalnutritionlawrencehaddadNo ratings yet

- SADC GNR Haddad FinalDocument33 pagesSADC GNR Haddad FinallawrencehaddadNo ratings yet

- FANUS Arusha Declaration 2015Document2 pagesFANUS Arusha Declaration 2015lawrencehaddadNo ratings yet

- Current Accountability Mechanism in Nutrition: Do They Work?Document27 pagesCurrent Accountability Mechanism in Nutrition: Do They Work?lawrencehaddadNo ratings yet

- Bureaucracy Today - No National Policy For MalnutritionDocument1 pageBureaucracy Today - No National Policy For MalnutritionlawrencehaddadNo ratings yet

- SUN Business Workforce Nutrition Policy ToolkitDocument14 pagesSUN Business Workforce Nutrition Policy ToolkitlawrencehaddadNo ratings yet

- We Can End MalnutritionDocument31 pagesWe Can End MalnutritionlawrencehaddadNo ratings yet

- Netherlands Global Nutrition Report RoundtableDocument41 pagesNetherlands Global Nutrition Report RoundtablelawrencehaddadNo ratings yet

- What Is An Enabling Environment For NutritionDocument37 pagesWhat Is An Enabling Environment For Nutritionlawrencehaddad100% (1)

- National Budget Analysis 2014 CSO-SUN Alliance LHDocument28 pagesNational Budget Analysis 2014 CSO-SUN Alliance LHlawrencehaddadNo ratings yet

- Economic Rationale For Stunting 2013 Hoddinott, Alderman, Behrman, Haddad, HortonDocument1 pageEconomic Rationale For Stunting 2013 Hoddinott, Alderman, Behrman, Haddad, HortonlawrencehaddadNo ratings yet

- Call For Nominations To The Independent Expert Group For The Global Nutrition ReportDocument5 pagesCall For Nominations To The Independent Expert Group For The Global Nutrition ReportlawrencehaddadNo ratings yet

- Double Burden of Malnutrition in South East Asia and The PacificDocument24 pagesDouble Burden of Malnutrition in South East Asia and The PacificlawrencehaddadNo ratings yet

- Breaking The Logjam of Malnutrition in Pakistan Islamabad Launch October 4, 2013, Lawrence HaddadDocument16 pagesBreaking The Logjam of Malnutrition in Pakistan Islamabad Launch October 4, 2013, Lawrence HaddadlawrencehaddadNo ratings yet

- Proposed Sustainable Development Goals and NutritionDocument1 pageProposed Sustainable Development Goals and NutritionlawrencehaddadNo ratings yet

- Call For Nominations To The Independent Expert Group For The Global Nutrition ReportDocument5 pagesCall For Nominations To The Independent Expert Group For The Global Nutrition ReportlawrencehaddadNo ratings yet

- Bigger Impacts of Agriculture On Nutrition : What Will It Take? by Lawrence HaddadDocument25 pagesBigger Impacts of Agriculture On Nutrition : What Will It Take? by Lawrence HaddadlawrencehaddadNo ratings yet

- India's Nutrtion Enigmas - Why They Must Not Be A Distraction From ActionDocument7 pagesIndia's Nutrtion Enigmas - Why They Must Not Be A Distraction From ActionlawrencehaddadNo ratings yet

- The Great Indian Calorie DebateDocument35 pagesThe Great Indian Calorie DebatelawrencehaddadNo ratings yet

- Narratives in African AgricultureDocument8 pagesNarratives in African AgriculturelawrencehaddadNo ratings yet

- Being A Doctoral Student at IDS July 14Document3 pagesBeing A Doctoral Student at IDS July 14lawrencehaddadNo ratings yet

- Country Commitments Nutrition For Growth Summit LondonDocument3 pagesCountry Commitments Nutrition For Growth Summit LondonlawrencehaddadNo ratings yet

- Global Evidence On Double Burden of MalnutritionDocument70 pagesGlobal Evidence On Double Burden of MalnutritionlawrencehaddadNo ratings yet

- Potential Land Suitability For TeaDocument26 pagesPotential Land Suitability For TeaGautam NatrajanNo ratings yet

- November 2022 Examination: Indian Institution of Industrial Engineering Internal Assignment For IIIE StudentsDocument19 pagesNovember 2022 Examination: Indian Institution of Industrial Engineering Internal Assignment For IIIE Studentssatish gordeNo ratings yet

- 6 Acop v. OmbudsmanDocument1 page6 Acop v. OmbudsmanChester Santos SoniegaNo ratings yet

- Activity Problem Set G4Document5 pagesActivity Problem Set G4Cloister CapananNo ratings yet

- BS 00011-2015Document24 pagesBS 00011-2015fazyroshan100% (1)

- Deped Tacloban City 05202020 PDFDocument2 pagesDeped Tacloban City 05202020 PDFDon MarkNo ratings yet

- CSCE 3110 Data Structures and Algorithms NotesDocument19 pagesCSCE 3110 Data Structures and Algorithms NotesAbdul SattarNo ratings yet

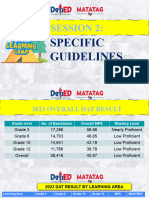

- FINAL Session 3 Specific GuidelinesDocument54 pagesFINAL Session 3 Specific GuidelinesBovelyn Autida-masingNo ratings yet

- Gustilo Vs Gustilo IIIDocument1 pageGustilo Vs Gustilo IIIMoon BeamsNo ratings yet

- HOS Dials in The Driver App - Samsara SupportDocument3 pagesHOS Dials in The Driver App - Samsara SupportMaryNo ratings yet

- 22 Caltex Philippines, Inc. vs. Commission On Audit, 208 SCRA 726, May 08, 1992Document36 pages22 Caltex Philippines, Inc. vs. Commission On Audit, 208 SCRA 726, May 08, 1992milkteaNo ratings yet

- QAQC Inspection Services Technical Proposal SummaryDocument69 pagesQAQC Inspection Services Technical Proposal SummaryMathias OnosemuodeNo ratings yet

- Modicon Quantum - 140DDI85300Document5 pagesModicon Quantum - 140DDI85300Samdan NamhaisurenNo ratings yet

- Restaurant P&L ReportDocument4 pagesRestaurant P&L Reportnqobizitha giyaniNo ratings yet

- Application For Freshman Admission - PDF UA & PDocument4 pagesApplication For Freshman Admission - PDF UA & PVanezza June DuranNo ratings yet

- E4PA OmronDocument8 pagesE4PA OmronCong NguyenNo ratings yet

- New Markets For Smallholders in India - Exclusion, Policy and Mechanisms Author(s) - SUKHPAL SINGHDocument11 pagesNew Markets For Smallholders in India - Exclusion, Policy and Mechanisms Author(s) - SUKHPAL SINGHRegNo ratings yet

- Whitmore EZ-Switch LubricantDocument1 pageWhitmore EZ-Switch LubricantDon HowardNo ratings yet

- Math30.CA U1l1 PolynomialFunctionsDocument20 pagesMath30.CA U1l1 PolynomialFunctionsUnozxcv Doszxc100% (1)

- Railway Reservation System Er DiagramDocument4 pagesRailway Reservation System Er DiagramPenki Sarath67% (3)

- Accor vs Airbnb: Business Models in Digital EconomyDocument4 pagesAccor vs Airbnb: Business Models in Digital EconomyAkash PayunNo ratings yet

- Summer Training Report On HCLDocument60 pagesSummer Training Report On HCLAshwani BhallaNo ratings yet

- Coca Cola Concept-1Document7 pagesCoca Cola Concept-1srinivas250No ratings yet

- Audit Report of CompaniesDocument7 pagesAudit Report of CompaniesPontuChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- FTC470XETDocument2 pagesFTC470XETDecebal ScorilloNo ratings yet

- The Ball Is Now in Their Hands': Lumumba Responds After City Council Rescinds Emergency DeclarationDocument2 pagesThe Ball Is Now in Their Hands': Lumumba Responds After City Council Rescinds Emergency DeclarationWLBT NewsNo ratings yet

- Socomec EN61439 PDFDocument8 pagesSocomec EN61439 PDFdesportista_luisNo ratings yet

- PTCL History, Services, Subsidiaries & SWOT AnalysisDocument18 pagesPTCL History, Services, Subsidiaries & SWOT AnalysiswaqarrnNo ratings yet

- CEMEX Global Strategy CaseDocument4 pagesCEMEX Global Strategy CaseSaif Ul Islam100% (1)