Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Debating 'Lenin and Philosophy'

Uploaded by

Ahmed RizkCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Debating 'Lenin and Philosophy'

Uploaded by

Ahmed RizkCopyright:

Available Formats

Debating Lenin and Philosophy

"Q and A" after Louis Althusser's presentation of his important 1968 lecture "Lenin and Philosophy."

Jean Wahl. I thank Monsieur Althusser very much for his communication, since communication there is. I think that in spite of himself something has happened, since the Societ Francaise de Philosophie has heard it, in a space yet to be defined. Now I am going to let Monsieur Ricoeur speak, if indeed he wants to . . . Paul Ricoeur. I would like to ask a question concerning the science you are talking about: does it exist and who are its scientists? Are they historians, or someone else? Louis Althusser. The science I'm talking about is a science of which there exist certain definite productions; it exists mainly in Capital, it exists in a certain number of other texts. I must say that until now historians have stayed very far away from it. The theory of history is something other than what historians do; the theory of history currently exists in a form that can be extracted from the texts in which it is recorded, above all in the analysis of the capitalist mode of production, that is, in Capital, in order to exhibit in an explicit form that I believe could renderI say so without exaggerationgreat service to historians. One cannot say that historians, I would even say many Marxist historians, have yet become aware of the fact that Capital contains theoretical elements that are capable of renewing in part the notions with which they work and on which they work. I also believe that historians, even inside their own practice, their historical practice, are led to pose problems for themselves, to restructure concepts in a sense that attests that Marx already preceded them for quite a long time in this elaboration. When one sees, for example, the effort that has been made, and which obviously is not inspired by Marxism, in the French Annales School, by Marc Bloch or by [Fernand] Braudel, who is currently the head or chief, one sees appear a certain number of concepts, including concepts of the longue dure, the courte dure, etc., that historians have expended a lot of effort and consciousness in elaborating, but which all the same remain quite vague; whereas when one studies Capital closely, one notices infinitely more precise concepts, which apply to the same objects by defining them infinitely better, having already been present there for a hundred years. Jean Wahl. Here you are leading us into a sphere of historical methodology; perhaps a partisan of the School you have cited wouldn't agree with you that Marx saw with greater precision what Braudel tries, with difficulty, to see. Louis Althusser. I don't mean at all that Marx saw a hundred years ago what Braudel sees now. No one who is serious can maintain that in a hundred years nothing has happened, of course, but what I meanand this is extremely strikingis that obviouslyand it is doubtless not the fault of historians alone, because I believe that intermediaries (relais) are necessary in cultural life and in history, even in scientific historythese historians, who produce quite remarkable works in relation to their own historical past, do not have, it seems to me, a knowledge of Capital, a truly sufficient knowledge of the concepts found in Capital. This is why it is not an insult to them to say so. Jean Wahl. I want to ask you if there isn't something arbitrary about accentuating in this way the importance of Capital and even, if one likes, the importance of History. Because there is indeed Marx, but you know extremely well that there is equally Freud, there are other

domains, the domain of physics, in which we are led to reflect precisely on the concepts of matter; and Lenin, one knows, was inspired by certain theorists of the physics of his time. It is striking that in Lenin's time there was [Pierre] Duhem, who Lenin knew about, there is a book called Physical Theory written by a Catholic, probably a reactionary, who was Duhem, and that Lenin approves of for the most part. But what I want to return to is the question of knowing if there is not something a little arbitrary in putting the historical sciences into the foreground. For the physical sciences pose problems anew, you said at the beginning: science unites and philosophy divides, and we see today that science doesn't unite as much as scientists do: there are philosophical differences, philosophical debates among scientists. It is very difficult to say that science unites physicists at the present moment: they are not very united on the question of determinism that somewho could at first glance only be called reactionarywant to maintain, whereas others think it cannot be maintained. Then there are scores of non-Marxist problems that can be added to the properly Marxist problems you have raised. Paul Ricoeur. My first question calls for a second. I would like to begin with your distinction of "regions," with the breaks that separate them. Does the epistemological act by which you represent these regions and which is therefore an activity of regional discernment bring you back to the alternative of materialism and idealism? It seems to me that these are two radically different philosophical situations; the second constitutes a metaphysical opposition, and I don't see why we should bear that burden, since we have the possibility of avoiding it with the distinction of regions. Moreover, if you want to account for the specificity of the region of history in relation to the region of nature, won't you be led to a problematic that will be either Kantian or Hegelian? It will be Kantian if you insist simply that it is a categorical order that supports the division into regions. It will be Hegelian if you insist on linking these spheres and at a given moment you produce something like the Hegelian spirit, that is, not spiritualism opposed to materialism but indeed, precisely, the totality of all the determinations that allow history to be distinguished from nature. In one hypothesis or the other you would have recourse to an epistemology of linking regions and not to the kind of alternative you are trying to impose on us, by a sort of ordering (mise en demeure) that seems to me absolutely foreign to the activity of constitution of the three regions. Louis Althusser. It is rather difficult to explain myself quickly on this question. I would simply say the following. One is always situated in relation to someone, but my reference would be neither Kant nor Hegel; it would be Spinoza. In other words, the general requirement of linking regions is for me a strictly ideological question, and I absolutely don't ask it. Paul Ricoeur. Yes, it is you who have asked it . . . Louis Althusser. No, it was Engels who spoke about the linking of regions, who said that science was in the process of linking its own regions; but I, absolutely not: there exist continents, I don't say at all that they have common borders, absolutely not: I am Spinozist, there exists an infinity of attributes . . . Paul Ricoeur. Yes, but Spinoza doesn't do that . . . He speaks of attributes, but he doesn't think about the plurality of regions. You can think about them together in some epistemological space . . .

Louis Althusser. I don't think about them together in some epistemological space, I think about them in their distinction . . . Paul Ricoeur. But you have indeed reestablished unity somewhere by forcing us to decide between materialism and idealism. Now I don't see how you can constitute this unity again on the basis of epistemological breaks: either you remain with these breaks, and there is a diversity of "trades" (mtiers), that of the historian, that of the physicist; or else, philosophically, you think about unity, and then I don't see that the one you have proposed responds to the question. Louis Althusser. Wait a minute. Let's try to classify the questions. You say: "I remain in the breaks and there are trades, and I don't think that this is very adequate." It is as if you said to me: "we remain in the economy and there are grocers," it is the same kind of thing. If you say that we remain in the breaks, this means that we remain in a theoretical domain, in which there is a history, etc. But a theory is not a trade. In other words, the artisans of this theory are really the people who have a trade, exactly like a grocer forms part of commercial capital, etc. Paul Ricoeur. I have taken "trade" in the sense of Marc Bloch, when he speaks about the "historian's trade," therefore in the sense of practice, and I don't see why one wouldn't have the right to do so. I am saying that these are different practices, and I thought I was proceeding in your sense by taking the words practice and trade. But what I mean is that the kind of thought in which you elaborate the idea of epistemological breaks seems irreconcilable to me with the kind of thought in which at the end you lead us by imposing on us the alternative of materialism and idealism. This alternative seems to me to be completely metaphysical and fictive. In other words, it seems to me that your end is much more regressive than what you had proposed in the methodological analysis from the beginning. Though you have never told us what this new science is, since you have not been able to show its scientists or objects or works. Jean Wahl. Yes, it is Marx . . . Monsieur Blanchard. Also, Monsieur Althusser, one is far from Marx; in the 1844 manuscriptsI don't really understand why you have left aside the 1844 manuscripts doesn't he seek precisely this unity to which Monsieur Ricoeur alludes? Jean Wahl. I would like to return to the alternative of materialism and idealism. I don't believe that this alternative is well posed, although Lenin, to whom we are paying homage, said that there is the existence of matter and the qualities of matter. To affirm the existence of matter is to be a materialist, and to be a materialist is to say that matter is something that always exists and whose existence must be affirmed. Louis Althusser. Philosophically speaking, according to Lenin, it is not the same scientific concept of matter that always exists, it is the category of matter . . . Jean Wahl. If you like: it is the category of matter. And every academic, traditional professor will say: one should instead sayit is easierrealism, idealism, spiritualism,

materialism. But you have divided up the idea of matter in such a way that there is, on the one hand, the existence of matter and, on the other hand, the various qualities of matter. . . . Louis Althusser. No, I have insisted on saying that for Lenin the materialist thesis was simultaneously a thesis of existence and a thesis of objectivity. Existence can be translated in all sorts of ways: the world exists, at any rate. The thesis of objectivity means objective knowledge, scientific knowledge, that's all. That matter exists, the thesis of materialism, doesn't mean anything else. I believe that you can actually find in Lenin a whole series of texts (when Lenin speaks of the opposition of the psychic, of sensations to matter), a whole series of texts that proceed in your sense. But I believe that Lenin's most profound thoughtand this is why I have spoken precisely of the fact that he spoke inside an empiricist, and even sensualist, problematicLenin's most profound thought proceeds in a completely different sense. For Lenin the category of matter is a philosophical category; this means that the matter of which the physicist speaks, that can be touched with the fingers, or at the limit that can be seen in the protocols of recording by scientific devices. The philosophical category of matter is never touched with the fingers, it doesn't materially exist, it is a thesis that functions philosophically in a certain way; and the problem is to study its philosophical functioning. But I am returning to what Monsieur Ricoeur said. I think that for an exchange to be fruitful, it must be clear, yet I perceive badly what he wanted to tell me, what point he is trying to make. . . . Perhaps there is a misunderstanding between us. Paul Ricoeur. Let us resume the discussion starting with what you have just said. What is the situation of the category of matter in relation to the three regions you have distinguished? Does it cover all three, or only one? Louis Althusser. Your question is pertinent, because it tightens the debate. I would say that what I have said regarding continentsbecause I prefer continents to regions, but that's not importantis something that can constitute the object of a history, of a history of sciences: what happens in the sciences. Now, how the sciences function, under what conditions, is that there is philosophy in the functioning of the sciences, in other words, philosophical categories preside over the process of the production of forms of knowledge, of this I am persuaded, but at any rate something happens in reality, it isn't commanded from outside. Now this is not at all what Lenin reflected on; he absolutely did not reflect on the problem of the unity of what I call these three continents. When I said that there was probably in the process of opening up before our eyes a new continent revealed to us by someone called Freud, who had to land somewhere, and by the fact that other disciplines are in the process of landing, it is still something that happens in the history of the sciences, which appears at one moment, which continues, etc. I simply note that, instead of posing the problem in terms of the unity of the totality of regions or continents, one notes on the contrary the striking, obvious autonomy of different continents. Something happens in mathematics, okay, which has relations with what happens in the continent of physics, very particular relations, which can be studied; all sorts of things also happen in the continent of physics. One even notes the fact that sciences like biology have been considered sciences of life. Now life is obviously an ideological notion that is in the process of disappearing. Something happens in the continent of history; and if one wants to think about everything that is happening in the continent of history, it is an immense domain. But all these facts don't concern first and foremost the problem of the unity of these different regions or different

continents that is, really, an immense problem that obviously haunts contemporaries. For a long time human beings have been haunted by this problem of the unity of different sciences, by the necessity for different sciences to account for the existence of their neighbors, that is, to insure going through customs and borders: to be sure of having a neighbor. When one is sure of having a neighbor, one is at ease, there are no histories. But Lenin completely makes fun of that, the problem of neighborhood is not at all the number one scientific problem: a science can evolve without a neighbor for a very long time, and enter into relations as if across a sea with a distant science. It is a fact, if you like, that between chemistry and its rightful neighbor, if I can say this, which is physics, there are relations that for a long time have been nonexistent then extremely loose, before becoming, only recently, very close. For example, who are the current neighbors of psychoanalysis? You see that a science can very well develop for a long time without a neighbor, and therefore the problem of thinking necessarily and a priori the unity of regionsthat is, an obligatory neighborhood, which would by force compel people to become neighbors, which would obligate sciences to become neighbors, to sit down side by side and to discuss, to say I am indeed the neighbor of my neighboris, as a philosophical requirement, an arbitrary, ideological requirement. Paul Ricoeur. Then your concept of matter is useless . . . Louis Althusser. But it has nothing to do with that! Paul Ricoeur. This is precisely what I wanted you to understand. If your concept of matter has nothing to do with that, then it is reduced either to be the extrapolation of the regional object of nature and means something, and then it is a stretch to extend it onto the three regions; or else it has no relation either with any one of them or with the three together, and then it means simply "there is" in its greatest generality. And that seems to me to be the most barren concept, since one could not even find something contrary to it. Louis Althusser. If you likebut from the point of view that I would try to defend on the basis of Marx's and Lenin's theoryI would say that a category has no oppositeit functions, and this isn't the same thing. To function in such a manner that it registers, that it provokes a conflict. But that having been said, it is certain that Lenin's formulations are not formulations that give the reader immediate satisfaction. I have wanted, when Lenin speaks of materialism, of matter, etc. to emphasize the things that seem most important to me. But when one studies all Lenin's texts from 1898 to 1905, which are texts of polemic against the populists, he speaks about political economy, he works on statistics; and Lenin wrote a book that all historians and all sociologists should read, which is called The Development of Capitalism in Russia, which is preceded by five volumes of studies on the situation of the peasants in Russia on the basis of statistical studies, surveys, etc. Monsieur Blanchard. You have just now said that Lenin was not at all preoccupied with the neighborhood of sciences. But Marx was preoccupied a great deal, he was precisely preoccupied with the unification of knowledge, of the unity of the sciences, therefore, of the relations that they can have among themselves. What do you think? Louis Althusser. You are speaking of the Marx of 1844, who was not Marxist but Feuerbachian-Hegelian. It is certain that when there is a real neighborhood, one has every

interest in noting it; but if there is no real neighborhood, in certain cases, it can be extremely unpleasant for everyone to force people to become neighbors. When one arbitrarily tries to force them to do so, it can have deplorable consequences for the neighbors in question. What I mean is that one shouldn't be too keen to make the sciences into neighbors. And if you want me to tell you the foundation of my thought, to allude to a publication I cannot name out of discretion, there is now being published in a weekly magazine the report of a roundtable discussionroundtable discussions are quite fashionableamong worldrenowned linguists, biologists, ethnologists, etc. A roundtable is a neighborhood, it is a salon in which one chats; when one has sat down together alongside others and when those who have sat down are scientists, they have the euphoric impression that their sciences are neighbors, and they begin to pass protocols of neighborhood: you are my neighbor, monsieur, I am your neighbor, one proceeds to exchange conceptsjust as rugby players exchange their jerseys. They exchange their concepts. The result can be read in the previously mentioned weekly magazine: each gives a little more than he can give in order to be sure of being truly the other's neighbor, that is, to be sure of saying what the other is in the process of saying on his side. Then, if you allow all that to rest a little while, put it into the archives, you will see some years later what it will yield. There are a certain number of declarations in these texts that those who have made them will no doubt be very proud to reread in a few years. Monsieur Blanchard. I agree with you, Monsieur Althusser, only I believe that one can consider, always while referring to the 1844 manuscripts you reject, it seems to me, rather blithely, that the neighborhood of the sciences is not only a salon conversation for Marx, but it represents for him the protocols of socialism. Louis Althusser. Think back to Engels's text (Ludwig Feuerbach [and the Outcome of Classical German Philosophy]): for Engels it is very important, and important not only for him but for everyone. It is not because one is a Marxist or an idealist, it is a fact that the relations among the sciences are very important. What I mean simply is that it is arbitrary to want at any cost to impose on the sciences a relation that isn't born spontaneously, that isn't really grounded in their own requirements, that's all. In other words, a premature synthesis shouldn't be imposed on the sciences. And I would say that synthesis is always premature. Engels had the feeling that others had before him, and that certain people have now, that we have arrived at the time of definitive synthesis. Lenin said simply: there will never be a definitive synthesis. This doesn't mean that there are no relations among the sciences, it means that there can never be a definitive synthesis, that it is never possible for the sciences completely to enclose themselves in a unity for which certain people are always on the lookout, or else passing among themselves protocols that insure the relations of a definitive good neighborhood. That doesn't mean that there don't exist some true relations among the sciences, but something else again are the real relations that can be relations that are extremely tight or extremely relaxed and that can also take on extremely complex forms, of which we are doubtless not always conscious, and that must be studied. But I believe it is profoundly anti-Marxist to want to impose on the sciences a unity that is of an obligatory neighborhood and that is declared philosophically. At any rate, it is not in this sense at all that Lenin worked. Although Engels thought that this was in the process of happening, that the sciences were in the process of uniting and of producing spontaneously the equivalent of the former philosophy of nature. For Lenin this is not the case at all. To want to ask the question like this, and with all one's might to impose a unity on the sciences, whatever the

moment, is an impossibility for him. If a unity exists among the sciences, it must be real and produced by the sciences themselves and not imposed from outside by philosophy. Jean Hyppolite. I would like simply to repeat Monsieur Ricoeur's first question. First of all, there are two breaks that perhaps shouldn't be confused. Onecall it the epistemological breakis when the scientificity of a science appears; the other, which is not of the same order (there is a very great difference), is the difference between the continents. Now if the scientificity of mathematics, of physics, of chemistry, and even of biology to the extent that it ceases to have an ideological concept at its foundation, if this scientificity is recognized, and if the break appears for this continent, it is much more difficult regarding history. Here we don't have such a recognition, probably because the continent is of a still different orderI don't thereby mean that it is spiritual, I set aside this problem. Perhaps the conception that Marxism can have of history, as Marx developed it, as you have rethought it, in a properly speculative way, if I dare say, perhaps only in effect, is more profound that certain descriptive, or globally mathematical, conceptions of the so-called modern human sciences, with their forms, their research, their samples, perhaps it is very different and very profound, but it would be necessary to see it close up. But let us recognize that the scientificity of this science, which is called historical materialism, is not easily recognizable, and that the science that establishes the scientificity of this science is not established for anyone who reflects. The scientificity of this science is, as, I believe, you said it at the end, finally dependent on a politics in certain respects. And in fact, this overturns things in relation to the continent of mathematicsif one calls it a continentand to the continent of physics. I believe that, it should be said, because then the conception of historical materialism is not recognized in all that. With regard to Lenin, I think that the Philosophical Notebooks were written after the book against empirio-criticism; I know the Philosophical Notebooks especially well, and it seems to me that the great admiration Lenin shows for Hegel, the astonishing way in which he copies Hegel, is as astonishing as the way in which he copies Abel Rey in the margin, "finale = shamefaced materialism." As for Hegel, Lenin says things that are very profound in the margins: he remarks, regarding the theory of the essence, that it indeed goes between the accidental and the essential, because between deep currents and the surface, the surface is very important in order to explain things. But for the theory of the concept, regarding the concept that is a subject, he says: I don't understand. Only what he asks Hegel, this is why he admires Hegel, just as this is why in certain respects he copies Abel Roy, it is because in no way does he want a philosophy of the thing in itself, it should be said, in this form. He doesn't want a philosophy of the thing in itself to be established that would make possible something else, something other than this problem of the sciences and of the scientificity of science, that is, that would make possible a belief on which he thinks that politics depends. Above alltell me if you don't agreethis struggle is fundamental. So that I only wanted to repeat Ricoeur's first question, not the second, not the question about the diversity of continents and unity, of a sort of unity that one indeed has the right to constitute if one wants: perhaps it will be done one day, when communism exists. But concerning science, if there is only scientific truth, there is nothing outside of science except ideologies, and the scientificity of a science that is at the same time an ideology isI believe that Marx explained it, if I can believe an article of yoursat the same time as it is responsible for its own break, it corrects itself, it strangely resembles absolute knowledge, to the point of a politics. Here is an ambiguity; do you agree?

Louis Althusser. Yes, I believe so. What seems important to me in what you have just said is the essential care that Lenin takes to break with a certain danger concerning the status of philosophy, at any rate concerning the nature of the theses of philosophy. Moreover, it is no accident that when he himself reflects on his own practice it is always to say: science must be prevented from becoming an ossified dogma, etc. This is to say that his philosophical intervention always has for its goal a liberatory role of scientific practice; and I truly believe that his most profound thought, even if, once again, it remains weighed down in expressions inherited from the 18th century, especially in his reference to the Berkeley-Diderot couple, his most profound thought is undeniably anti-positivism. Now this is not what is generally believed concerning Lenin's thought. The problem you emphasize is then a very important problem. I believe that one can, obviously, not be in agreement at all on what I indicate here, namely, that Leninand he is doubtless not the only onebecame aware of something of which philosophy has a hard time becoming aware. The idea that philosophy, first of all, is something that functions in a special way, that functions in philosophersit is not philosophers who make the philosophy in their philosophiesthat it functions and that this functioning can be studied, and that this functioning puts a certain number of moments into relationship. This is extremely important, it is a domain of research on which one can easily agree once certain prejudices have been overcome. Relatively speaking, this is rather comparable to what Freud did in an entirely different domain. But the most pertinent question that you ask really concerns what happens in the science of history, historical materialism. I said that it was a very original idea, very striking, very particular, and it is clear that Lenin insists on it a great deal. The entire Marxist tradition insists on saying that Marx founded a science. Marx himself believed it. It is certain that in the elaboration of his scientific thought Marx constantly uses references to the existing sciences: mathematics, chemistry, astronomyespecially chemistry. And only next, if you like, comes the question of the modality of existence of scientific forms of knowledge or of the conditions of existence of the sciences that can develop on this completely particular continent that is History. And I think that certain of these unique characteristics have been as is often the caseand here I maintain an entirely classical Leninist thesiscertain of the particularities of this new continent have been expressed in a form that Lenin would say is necessarily distorted, turned away from its object, etc., by a certain side of idealist philosophy, who said that this doesn't happen in the sciences of history or in history quite as easily as in the sciences of nature. It is true that the science of history is a science, but not like the others. One knows that this difference has been exploited by idealism, in particular by Dilthey and his successors. The problem is to know what is the real differenceand where it must be situated. It is a major question, and not necessarily a question to which one can easily respond. This is why I wouldn't say that humanity only poses problems it can, at least immediately, resolve. Instead I would say the contrary, I would say that humanity only finds a response to problems that it can pose. This I believe is Marxist. Humanity can only resolvefrom the point of view that interests us, in particular the problem of historical materialismthe problems it can pose. I believe that, despite its difficulty, we are in a state of posing the problem of the definite and differential specificity of the conditions of the scientificity of the continent of history in relation to the continent of physics. You tell me that it is premature, but one already possesses important elements, and you find these elements in Lenin not at all either in the book against Empirio-criticism or in the Philosophical Notebooks but in his textual studies on Marx, in the work on economic analyses, and especially in his political works. Here there are extremely interesting things, Lenin explains what he encounters, he encounters things but he doesn't always render account of them. But, encountering them, he always thinks them by

identifying them; now in all these scientific texts which are texts of a sociologist, he distinguishes two things: objectivity and objectivism; and he spends his time polemicizing against the sociologists, for he lived at this time in Russia, since it was they who came up with the statistics on which everyone worked and that one interpreted. Lenin counterinterprets them and he opposes his methodology to that of the economists, and here there was a whole series of extremely interesting epistemological reflections could be added to the file if one wanted to know how to think the differential specificity of the scientificity of the continent of history in relation to the continent of nature, to the continent of mathematics, etc. I believe that soon this problem will be in a state of being posed; but to want to resolve it before having posed it, is, I admit, properly mythological. P.-M. Schuhl. I would like simply to reveal a distortion of practice in relation to one of the problems that have been indicated just now. I don't know if you know that four years ago a certain number of scientists decided, at the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, that philosophy should disappear. And it was already almost realized, but at the last moment, the existence of a section of philosophy was saved under the title of history and methodology of sciences. Well! I believe that, nonetheless, if one can discuss historical materialism anywhere it is indeed in a department of philosophy. Louis Althusser. I am indeed in agreement. I have said that philosophy won't disappear, which means that we have the conviction that it must not disappear. And I think that we owe part of its existence to Monsieur Schuhl. J.-P. Faye. I would like to make the following remark: what has struck me in what Louis Althusser said is that for him philosophy is no longer the history of philosophy to which it has seemed to be reduced, with the entrance of a certain "Hegelianism" in the philosophical present moment. What is philosophy in relation to its own history? Louis Althusser has just told us: it is a history within philosophy. That is, philosophy constitutes for us at this moment philosophy, it is what produces an entrance of history into philosophy. The end of this process insures that philosophy is no longer simply the reading of its own null trace, it is no longer simply the narcissistic reading of its own trace, what it seemed to be and what it seemed reduced to being until the end of time. From this perspective philosophy would be this sort of envelope of a process generative of history. And if it is discovered that Lenin is, in fact, in modern times, this first "philosopher," or this first philosophizing individual, who has produced history. Then I would like to ask a question: what are the relations between this production of a history by a philosophy itself pointed, by science, at reality, and let us say: its method of verification? By what criteria of "truth" or verifiability must it be defined as a rule in order to be capable, really, of this generative process, of this process that makes one think at times of that of a generative grammar, the "process of production" of a discourse. Leninist philosophy, dialectical materialism, as a theory of the production of a science of history appears to us as this sort of grammar of a history, whose discourse leads to a political process of "verification." Then what relations can one try to sketch, or determine, between this fundamental process of recording and this verification in practice? Louis Althusser. Would you repeat your question? J.-P. Faye. I'll be more succinct. Philosophy is no longer simply the history of philosophy, but it has entered, with Marxism, into a theoretical practice that makes it take up again the

previous history without being content to reread it. Then the well-known Leninist text that, moreover, has been highlighted in the wake of your lesson"the theory of Marx is powerful" and even "all-powerful" in history "because it is true"this Leninist thesis shows that there is a relation, that there must be a precise relation between the productive power of Marxist theory, simultaneously a philosophy of sciences and a science of history, and on the other hand its dispositif of "truth." Louis Althusser. I didn't understand your first question. But, on the other hand, I cannot respond to the second for a simple reason: I believe that the formula Marxist theory is allpowerful because it is true has no meaning for philosophy. That is, Marxist philosophy cannot be "true"; what is true is the science of history, that's all. The category of truth is not pertinent for philosophy. Although philosophy always speaks of truth, and only speaks of truth, the category of truth is not pertinent in a proposition of philosophy. J.-P. Faye. Of course. But it is philosophy that founds the category of truth in the science of history. How then does it do so in order to construct this category of truth? Louis Althusser. Since Lenin breaks precisely with the idea that philosophy could found something, not only Lenin but also Marx breaks with this idea. The idea that philosophy could have something to found is one of the ideas that is fundamentally foreign to what is called Marxist philosophy. J.-P. Faye. Fine. Found is perhaps not a suitable word. Instead let's say determine. And does the articulation, the explication, the clarification of a scientific concept in its relation with a philosophical category indeed arise from the task of philosophy in the Leninist sense of the word? Louis Althusser. Not necessarily. J.-P. Faye. But you say: science needs the category (of truth) in order to test its concepts (of verification). This would be to do it "falsely" . . . Louis Althusser. I would say, on the contrary, that science must be wary of the category of truth. J.-P. Faye. Yes? Then science is wary of truth with what instrument? What conceptual instrument? Louis Althusser. You want me to respond to a question that depends on a philosophy that you have up your sleeve, namely, your own. I don't believe it is necessary to engage in this way in a simulacrum of public self-birthing. Jean Wahl. All the same you been guided by the idea of truth. One moment you said, "the truth is that." You are forced, and it is not in order to do philosophy but to express oneself, you are forced to say: the ideas of Lenin are found, in particular, on the basis of a certain era, in a certain doctrine on the development of capitalism in Russia. And I don't know if it is at this moment that the idea of truth is introduced; but basically, one cannot think

without this being understood, namely, that there is a truth. And you are in agreement, since you yourself have spoken of objectivity and objectivism. J.-P. Faye. What is important is what you just said: what is true is the science of history. But Lenin's Philosophical Notebooks and even more so Materialism and Empirio-criticism are very often applied to justify the idea of the "truth" that cannotand it is in this that there is the break with Hegelian idealism of which you spoke a little while agothat cannot be present in the beginning of the procedure, but, Lenin says, which is going to be constituted or determined in the continuation. I believe that here is where one rediscovers what you were saying: it is at the level of science or of political practice that this continuation is determined, is revealed. But this "continuation" is controlled by the very attention that is going to be applied to the verification of the scientific process, or of political practice. Through epistemology itself, that is, the philosophical procedure of which you spoke, this procedure which, through the work of Bachelard, or Cavaills, or Canguilhem, helps us to produce notions like epistemological break. Now what makes the notion of epistemological break pertinent if not the division, the demarcation that it operates between the strictly ideological domains of the nonverifiable arising from the psychoanalysis of knowledge in the sense of Bachelard and, on the other hand, the verifiable practice of the scientist? Here I believe that even so we are in a region in which the "category" of truth and the concept of the verifiable intervene on the boundaries, if one can say it, of philosophical thought and of thought such as science. Would you agree, in this sense, on this notion of "boundary" (confins)? Louis Althusser. It is quite difficult to come out in agreement or not with a notion that belongs to a discourse you cannot explain thoroughly. What I can say is simply what forms part of my own discourse. If you speak about the notion of truth, I would tell you it is an ideological notion, that's all. R. P. Breton. I would like to offer three remarks: 1. First of all, in order to get out of the rut of academic discussions about materialism/idealism, it seems to me urgent to refer to the first chapter of Materialism and Empirio-criticism. What strikes me in this first chapter is the resemblance between the Leninist critique of psychologism and the Husserlian critique of psychologism. This psychologism, for Husserl as for Lenin, can in fact be summarized in the famous: Esse est percipi. For both this affirmation summarizes what is essential to psychologism. Thus we have: a) A first definition of psychologism by this affirmation. b) A definition that is explained in the following propositions: psychologism includes, on the one hand, the identification of the sensed (of the cogitatum in the Husserlian sense) with the "real" thing; on the other hand, an identification of the sensed (or of the cogitatum) with the act of the senser or of the perceiver. c) Now this double identification leads, according to Lenin, to a contradiction; according to Hegel it leads to nonsense. For my part I prefer this second terminology and recall with the logician that the "non-sensed" is not even "contradictory." According to Husserl's details, we shall say that the principle of psychologism is doubly Sinnlos: because it mixes up, on the one hand, the language of the object with that of the idea (the idea of the triangle is not a triangle; after Spinoza, Frege will recall this with the technical means of modern logic); because it confuses, on the other hand, the language of the idea (of the intentional correlative according to Husserl) with that of the act (a distinction taken over from the Stoic

and Medieval tradition). In other words, to attribute the properties of the real object to the idea or to the act is to compose an Unding that can have no place in logic or in philosophy. It would be like speaking about the color of the number "three." d) But here Lenin goes further and Husserl wouldn't be able to agree with him. For Lenin psychologism is the very definition of idealism, such as he understands it in his strict sense, which is for him subjective idealism. If one relates psychologism and idealism, one perceives, he thinks, that the first is the essence of the second, whatever the various forms under which historically it also masks this essence. e) This isn't all. A third stage of the reflection, which links Lenin to Engels, allows him to identify the theological source of this idealism, which would be, as Feuerbach had said, its secular version. In order to understand this last affirmation, it should be recalled that theology, according to its critics, substitutes for the principle of the real, by an inversion in meaning, a creative idea, a thought that moreover, by virtue of the famous Aristotelian definition, is the "thought of thought," that is, as St. Thomas will later comment, the identity of thinking, of the act of thinking, of the thing thought, and the principle of thinking. It thus turns out, if we follow the filiation of doctrines, that one can determine a historical or logical genealogy of idealism. Everything happens, in fact, as if the idealist doctrines were only modes (in the Spinozist sense) of the primordial theological "nonsense" that would be its generative monad. f) If one follows the internal logic of this first chapter I am trying to reconstruct, one then understands the two consequences Lenin draws out from his analysis: 1) if empirio-criticism is indeed the last avatar of psychologism and, consequently, of idealism and "theologism," it is impossible for "science" (permit me this "abstraction") to be recognized in "consciousness" or in interpretation, or if one prefers the "image" empirio-criticism offers of itself. For this image, when one looks at it fixedly, vanishes into an Unding. A science with an empirio-critical dimension should share the "nonsense" of its supposed foundation. 2) Yet insofar as it is ideology "nonsense" in the dimension of the theoretical regains a meaning that is then a power. It seems that Lenin will recognize this power of the absurd within the "theological" insofar as it is a politics. Here again the theological would be "original." 2. My second remark concerns a secondary point but one that appears to me not to be without importance. I refer, since we are in a French context, to the discussion that Lenin makes of the "French epistemological triangle" (permit me this name): Poincar, Le Roy, Duhem. Perhaps he excessively simplifies the situation. The problem posed to these epistemologists less concerns matter (or its eventual "vanishing" into Ostwald's energetics) than the concept of scientific fact that is certainly neither something "ready made" that a reflecting abstraction would suffice to establish; nor a pure "being of reason" fabricated from all pieces for the pleasure of coherence alone. Althusser would speak instead of "production"; others had preferred to speak of "constitution." These two languages don't overlap. I think that the confrontation of these two languages would today be more instructive than the discussions about the hard opposition of idealism-materialism. 3. What you have said about the category of matter appears to me very important. Here there is, inside of Marxism, the initiation of an epistemological reflection, which could mark a turning point. And here I am not sure that Lenin had taken all the necessary precautions. I have the impression that he slides, without warning, from matter-category to matter-thing, although, I willingly recognize, he distinguishes carefully the different scientific representations of matter from that of which they would be the representations. Strictly speaking, and if we want to avoid the nonsense to which the confusion of languages leads us, it would be necessary, it seems to me, to reserve the category of matter for "dialectical

materialism," which is, if I understand you well, on the level of meta-language, and to refer the different concepts of matter to the disciplines that explore the multiple continents you have noted and that utilize an object-language. This would lead me to a final question about the epistemological status of dialectical materialism. But it would take too long for us to explain it. I would venture a simple hypothesis. You said that Cartesian philosophy elaborated, in accordance with Galilean physics, a new category of causality. Could one propose, using this as a precedent, that the main task of dialectical materialism would be the elaboration of historical materialism, considered as a "knowledge"? Once again, I only wanted to ask a question. Louis Althusser. I thank Father Breton for his intervention that carries very important details, and I would be happy to discuss it at length with him. Jean Wahl. I believe we can close the meeting, by thanking Monsieur Louis Althusser very much and all those who have spoken. (Translated by Ted Stolze from Bulletin de la Socit franaise de Philosophie, volume LXIII, 1968, pp. 161-81.)

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Discovering The Scientist Within Research Methods in Psychology 1st Edition Lewandowski Test Bank 1Document22 pagesDiscovering The Scientist Within Research Methods in Psychology 1st Edition Lewandowski Test Bank 1brian100% (36)

- Heidegger's Question of Being Explored Through Meaning, Excess, and EventDocument28 pagesHeidegger's Question of Being Explored Through Meaning, Excess, and EventAhmed Rizk100% (1)

- Brassier Interview 2Document8 pagesBrassier Interview 2Vi LeNo ratings yet

- Bruno Latour - An Attempt at A Compositionist ManifestoDocument20 pagesBruno Latour - An Attempt at A Compositionist ManifestoGuilherme KujawskiNo ratings yet

- (Werner Jaeger) Paideia The Ideals of Greek Cultu (BookFi - Org) Vol3Document383 pages(Werner Jaeger) Paideia The Ideals of Greek Cultu (BookFi - Org) Vol3Stjepan PalajsaNo ratings yet

- Alexandre Kojève - The Emperor Julian and His Art of WritingDocument19 pagesAlexandre Kojève - The Emperor Julian and His Art of WritingAhmed Rizk100% (1)

- Hans Jonas - Heidegger and TheologyDocument28 pagesHans Jonas - Heidegger and TheologyVjacheslav Tsyba100% (1)

- Parkinson - 1981 - Kant As A Critic of LeibnizDocument14 pagesParkinson - 1981 - Kant As A Critic of LeibnizAhmed RizkNo ratings yet

- Barash - 1998 - The Sense of History On The Political Implication PDFDocument14 pagesBarash - 1998 - The Sense of History On The Political Implication PDFAhmed RizkNo ratings yet

- Philosophy of The Morning - Niet - Tracy B. StrongDocument15 pagesPhilosophy of The Morning - Niet - Tracy B. StrongAhmed RizkNo ratings yet

- Green - 2014 - Book Review The Constitution of Capital Essays oDocument23 pagesGreen - 2014 - Book Review The Constitution of Capital Essays oAhmed RizkNo ratings yet

- Succession To Rule in The Shiite CaliphateDocument27 pagesSuccession To Rule in The Shiite CaliphateAhmed RizkNo ratings yet

- Ibn 'Arabi's Theory of The Perfect Man and Its Place in Islamic ThoughtDocument184 pagesIbn 'Arabi's Theory of The Perfect Man and Its Place in Islamic ThoughtAhmed RizkNo ratings yet

- Malabou PDFDocument13 pagesMalabou PDFdicoursfigureNo ratings yet

- Charitable Interpretations and The Political Domestication of SpinozaDocument20 pagesCharitable Interpretations and The Political Domestication of SpinozaAhmed RizkNo ratings yet

- An Interview With Benny MorrisDocument13 pagesAn Interview With Benny MorrisAhmed RizkNo ratings yet

- Peter Minowitz - What Was Leo Strauss?Document10 pagesPeter Minowitz - What Was Leo Strauss?Ahmed RizkNo ratings yet

- Pippin - Agency and Fate in Orson Welles's The Lady From ShanghaiDocument31 pagesPippin - Agency and Fate in Orson Welles's The Lady From ShanghaiAhmed RizkNo ratings yet

- SI - All The King's MenDocument4 pagesSI - All The King's MenAhmed RizkNo ratings yet

- On Heidegger and The Metaphysical QuestionDocument27 pagesOn Heidegger and The Metaphysical QuestionLuis FelipeNo ratings yet

- The Desire For Recognition in Plato's 'Symposium'Document27 pagesThe Desire For Recognition in Plato's 'Symposium'Ahmed RizkNo ratings yet

- Laruelle Francois Truth According Hermes Theorems Secret and CommunicationDocument5 pagesLaruelle Francois Truth According Hermes Theorems Secret and CommunicationchinchillaNo ratings yet

- Iain Thompson - On The Advantages and Disadvantages of Reading Being and Time BackwardsDocument18 pagesIain Thompson - On The Advantages and Disadvantages of Reading Being and Time BackwardsAhmed RizkNo ratings yet

- Caring For Myth: Heidegger, Plato, and The Myth of CuraDocument13 pagesCaring For Myth: Heidegger, Plato, and The Myth of CuraAhmed Rizk100% (1)

- Essay On Transcendental RealismDocument44 pagesEssay On Transcendental RealismSamira SyedaNo ratings yet

- Laruelle (Pli 8)Document11 pagesLaruelle (Pli 8)Ahmed RizkNo ratings yet

- Sean Kelley - The Rebirth of WisdomDocument13 pagesSean Kelley - The Rebirth of WisdomAhmed RizkNo ratings yet

- Sinnerbrink, Robert - The Hegelian 'Night of The World'. Zizek On Subjectivity, Negativity, and UniversalityDocument21 pagesSinnerbrink, Robert - The Hegelian 'Night of The World'. Zizek On Subjectivity, Negativity, and UniversalitydusanxxNo ratings yet

- John Ruskin - The Stormcloud of The Nineteenth CenturyDocument10 pagesJohn Ruskin - The Stormcloud of The Nineteenth CenturyAhmed RizkNo ratings yet

- Heidegger On SinnDocument14 pagesHeidegger On SinnAhmed RizkNo ratings yet

- BRM Syllabus & Lesson PlanDocument4 pagesBRM Syllabus & Lesson PlanjeganrajrajNo ratings yet

- Assignment02 - 60162020005 - Daud Wahyu Imani - Tugas Uji HipotesisDocument27 pagesAssignment02 - 60162020005 - Daud Wahyu Imani - Tugas Uji HipotesisDaud WahyuNo ratings yet

- Sample: Interference Testing in Clinical Chemistry Approved Guideline-Second EditionDocument12 pagesSample: Interference Testing in Clinical Chemistry Approved Guideline-Second EditionSvetlana MorozovaNo ratings yet

- Sinharay S. Definition of Statistical InferenceDocument11 pagesSinharay S. Definition of Statistical InferenceSara ZeynalzadeNo ratings yet

- Growth Monitoring of VLBW Babies in NICUDocument18 pagesGrowth Monitoring of VLBW Babies in NICUInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Use of Control Charts: 4.5.2 Internal Quality Control in The Microbiology LaboratoryDocument1 pageUse of Control Charts: 4.5.2 Internal Quality Control in The Microbiology LaboratorythisiscookingNo ratings yet

- Forecasting Techniques Under 40 CharactersDocument55 pagesForecasting Techniques Under 40 CharactersDevanshu Sahay100% (1)

- COMBINED SCIENCE1 Min PDFDocument100 pagesCOMBINED SCIENCE1 Min PDFLovemore MalakiNo ratings yet

- CH 01Document49 pagesCH 01m m c channelNo ratings yet

- The Cosmic Microwave Background by R Durrer PDFDocument3 pagesThe Cosmic Microwave Background by R Durrer PDFShreetama PradhanNo ratings yet

- Imperial Journal of Interdisciplinary Research (IJIR) - A Study On The Customer's Expectation and Perception of Service Quality of Retail Grocery Stores Using SERVQUAL Model PDFDocument6 pagesImperial Journal of Interdisciplinary Research (IJIR) - A Study On The Customer's Expectation and Perception of Service Quality of Retail Grocery Stores Using SERVQUAL Model PDFayyamperumalrNo ratings yet

- Data Science CourseDocument50 pagesData Science CoursearohiNo ratings yet

- Real Statistics Examples Non Parametric 1Document132 pagesReal Statistics Examples Non Parametric 1MeNo ratings yet

- Tipus Mikropipet 1 PDFDocument10 pagesTipus Mikropipet 1 PDFAnnisa Amalia0% (1)

- STC-MWC SC Grade 2Document6 pagesSTC-MWC SC Grade 2Perihan SayedNo ratings yet

- Determining The Value of The Acceleration Due To Gravity: President Ramon Magsaysay State UniversityDocument12 pagesDetermining The Value of The Acceleration Due To Gravity: President Ramon Magsaysay State UniversityKristian Anthony BautistaNo ratings yet

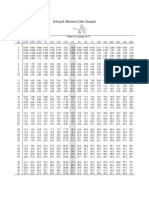

- Erlang B Table for Blocked Call AnalysisDocument4 pagesErlang B Table for Blocked Call AnalysisSardar A A KhanNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Physics: Arlyn Joy D. Olaira Physics TeacherDocument17 pagesIntroduction To Physics: Arlyn Joy D. Olaira Physics TeacherArlyn Pong Pling PioNo ratings yet

- Barnett V. (1976) The Ordering of Multivariate Data PDFDocument39 pagesBarnett V. (1976) The Ordering of Multivariate Data PDFJudith LugoNo ratings yet

- Nominal, Ordinal, Interval, Ratio Scales With Examples: Levels of Measurement in StatisticsDocument10 pagesNominal, Ordinal, Interval, Ratio Scales With Examples: Levels of Measurement in Statisticsanshu2k6No ratings yet

- LESSON 1 Quantitative Research Characteristics and ImportanceDocument23 pagesLESSON 1 Quantitative Research Characteristics and ImportanceRj Ricenn Jeric MarticioNo ratings yet

- Business Statistics End Term Exam QuestionsDocument5 pagesBusiness Statistics End Term Exam QuestionsShani KumarNo ratings yet

- 5 Postulates of Quantum MechanicsDocument23 pages5 Postulates of Quantum MechanicsKhaled AbeedNo ratings yet

- Accuracy and Use of InformationDocument2 pagesAccuracy and Use of InformationAlexdorwinaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7: Comparison of Two Groups: P P Se P P Se y y Se y y M MDocument12 pagesChapter 7: Comparison of Two Groups: P P Se P P Se y y Se y y M MŞterbeţ RuxandraNo ratings yet

- Cronbach's Alpha Reliability Analysis 20 VariablesDocument1 pageCronbach's Alpha Reliability Analysis 20 VariablesHaroem Perfume3in1No ratings yet

- Entre CoopDocument32 pagesEntre CoopsimongarciadevillaNo ratings yet

- Experimental Design - Chapter 1 - Introduction and BasicsDocument83 pagesExperimental Design - Chapter 1 - Introduction and BasicsThuỳ Trang100% (1)