Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Everyday Ethnicity China

Uploaded by

AnthriqueCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Everyday Ethnicity China

Uploaded by

AnthriqueCopyright:

Available Formats

This article was downloaded by: [Ala Uddin] On: 09 January 2013, At: 07:56 Publisher: Routledge Informa

Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Asian Ethnicity

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/caet20

The politics of everyday ethnicity in China

Elena Barabantseva

a a

Department of Politics, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK Version of record first published: 26 Oct 2011.

To cite this article: Elena Barabantseva (2011): The politics of everyday ethnicity in China, Asian Ethnicity, 12:3, 355-361 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14631369.2011.605873

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-andconditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Asian Ethnicity Vol. 12, No. 3, October 2011, 355361

REVIEW ARTICLE The politics of everyday ethnicity in China

Elena Barabantseva*

Department of Politics, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK

Downloaded by [Ala Uddin] at 07:56 09 January 2013

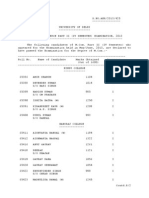

Doing business in rural China: Liangshans new ethnic entrepreneurs, by Thomas. Herberer. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 2007, 268 pp., 32.30 (hardback), ISBN 978-0295987293. Communist Multiculturalism: Ethnic Revival in Southwest China, by Susan McCarthy. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 2009, 226 pp., 14.44 (paperback), ISBN 978-0295989099. Autonomy, Ethnicity, and Poverty in Southwestern China: The State Turned Upside Down, by Chih-yu Shih. New York, NY: Palgrave, 2007, 268 pp., 42.75 (hardback), ISBN 1403984468. The launch of Chinas economic reforms in the late 1970s oered many opportunities for new research on Chinese cultural and ethnic diversity, and led to the publication of a myriad of scholarly studies on Chinas ethnic groups. With the recent ethnic clashes in Xinjiang in 2009 and in Tibetan areas in 2008, ethnic relations in China have been increasingly high on the political agenda of Chinas leadership and captured the attention of the audiences worldwide. However, the popular and journalist accounts rarely take notice of Chinas minorities beyond the Tibetans and Uyghurs. If they do, the Uyghur and Tibetan cases often serve as the lenses for perceiving other ethnic minorities lives in China. The prevailing popular accounts present ethnic minorities as suppressed and marginalized people who struggle to express their non-mainstream identities beyond the child-like or rebellious portrayals imposed on them by the Chinese state.1 The three books under review here provide an eye-opening analysis for those who might think of Chinas minorities as submissive subalterns or resistant Others. The recently published studies by Thomas Herberer, Susan McCarthy, and Chih-yu Shih present a complex and diverse picture of how ethnic minorities in China negotiate their agency and shape their identities under current socio-economic transformations. The eld of Chinas ethnic minorities has been mainly dominated by anthropological and historical studies, and it is especially important that these books are written by political scientists representing three scholarly cultures Taiwan, the

*Email: e.v.barabantseva@manchester.ac.uk 1 Wong, Theme Parks.

ISSN 1463-1369 print/ISSN 1469-2953 online 2011 Taylor & Francis http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14631369.2011.605873 http://www.tandfonline.com

356

E. Barabantseva

Downloaded by [Ala Uddin] at 07:56 09 January 2013

USA, and Germany. One striking similarity among the books is that they employ a long-term ethnography as a primary research method. Thus, they show the importance of a longitude on-ground research for political science, the research method unpopular across the disciple. Using dierent theoretical tools and conceptual frameworks 7 cultural and social theories (McCarthy), a poststructuralist approach (Shih), and a comparative study of ethnicity and entrepreneurship (Herberer) these studies contribute to the debates on the place of ethnic minorities in Chinese society, Chinese citizenship, and Chinese national identity. In other words, they problematize the construct of the Chinese nation from the perspective of ethnic minorities. Susan Blum identied that the overview of the whole Chinese nation was missing from the anthropological works on Chinese ethnic minorities published in the 1980s and 1990s.2 Taking a perspective of their chosen ethnic groups in Southwest China, these three books go beyond examining dissent, resistance and ruptures in the Chinese national identity to enquire into how ethnic minorities interpret their roles and identities within the structure of the Chinese state. The authors do not approach the study of ethnic identity set in opposition to the state and the dominant Han majority, but identify the ways in which being Chinese is integral to being ethnic in China. In what follows I summarize the common themes running through these three studies distinguishing them from the earlier analyses. I also identify the ways in which these books push the discussions on ethnic issues in China in new directions. Everyday ethnicity and membership in the Chinese nation The common feature of these books is that although ethnicity occupies a central place in their analyses, it is treated as a feature of ordinary life rather than a peculiar aspect of Chinese society. While many earlier published studies are aimed at disrupting the myth of Chinas cultural and ethnic homogeneity and at revealing the diversity of its society, these books treat ethnicity as a normal component of Chinese society in the areas that they discuss. Herberer, for example, shows how ethnicity is not merely a marker of dierence and distinction imposed by the state classication system, but a feature of daily relationships in Liangshan Perfecture of Sichuan Province (Herberer, p. 173). Similarly, the struggles of being ethnic and Chinese citizens are the daily experiences for the Bai, Hui, and Dai in Yunnan in McCarthys study and for the dozen minority groups across the provinces and autonomous areas in Chinas Southwest in Shihs book. It is not to say that the authors do not recognize the importance of the state and the market forces in the articulations of ethnicity. Shih stresses the role of state in framing ethnic identities in particular terms through its policies of autonomy, poverty, and modernization. McCarthy emphasizes the role of the market in commoditizing of minority culture, religion, and history as a developmental goal of the state (McCarthy, p. 8). Herberer views the market values as one of the shaping forces of ethnic relations in Liangshan. Yet, the authors stress that ethnicity in China takes a variety of forms not limited to the ones delimited by the state and the market, and that it is expressed dierently on a daily basis. Minorities very engagement with and interpretation of the state policies and their membership in the Chinese nation are premised on how they interpret their

2

Blum, Margins and Centers, 1302.

Asian Ethnicity

357

Downloaded by [Ala Uddin] at 07:56 09 January 2013

ethnicity. Ethnicity is at the centre of their formulations of being Chinese or, as McCarthy puts it, their being minority is one way of being national (McCarthy, p. 9). Throughout the books, ethnicity does not come across as an aspect of Chinese society the true nature of which is in need of being identied and recorded. Instead, we come to see ethnicity as an aspect shaping peoples political, social, and cultural lives. Ethnic minorities are not the groups in need of being discovered any more, but better understood and appreciated in the political and socio-economic contexts in which they live. This ordinariness of ethnicity comes in contrast to many previous studies on ethnic minorities in China that treat ethnic identities as the sites of Otherness, dierence, submission, or resistance. While here they are also presented as the sites of tensions, ethnic minorities are primarily approached as the citizens of China who actively negotiate and perform their citizenship through interpreting their countrys past, present, and future and their roles within these processes. The authors imply the irrelevance of separatism and anti-state sentiments among the groups they researched. Although these groups practice dierent ways of being ethnic and constantly negotiate their agency, they situate their identities rmly within the framework of the Chinese state and its history. The authors show that even if resisting certain state policies, minorities do not seek to undermine the legitimacy of the Chinese ruling party (McCarthy, p. 39). Minorities appeal to a variety of practices, including entrepreneurial, environmental, religious, and cultural, not to question the authority of the state but to nd their own niche within Chinese society. Even when they become aware of their assimilation into the dominant Han culture, like the Mulao in Guangxi in Shihs study, ethnic minorities claim their right to a distinct identity (Shih, p. 188). They are aware of their autonomous jurisdiction and reassert their cultural rights by appealing to the institutions available to them. Thus if opposing the policies of the Party and governmental authorities, ethnic minorities do it through engaging with the state not resisting it or, as McCarthy succinctly puts it, minorities wave the red ag to oppose the red ag (p. 10). Poverty, modernization, and entrepreneurial zeal One of the critical challenges faced by ethnic minorities in contemporary China is how to reconcile the dilemma of preserving their ethnic status associated with poverty and backwardness and the modern market values embraced by the Chinese state as the guiding principles for the countrys development. Poverty as a characteristic of ethnic minorities and an impediment to their development runs through the three studies. The most common explanations of poverty among ethnic minorities given by the Chinese authorities are the arguments of backwardness, traditionalism, conservative mentality, and geographical remoteness. In other words, at central and local policy-making levels ethnicity and the culture of poverty are treated as forming a symbiotic relationship, where poverty, attributable to cultural and geographical causes, becomes an inalienable feature of ethnic identity. This ocial view is most visibly manifest in the government campaigns aimed at poverty alleviation, such as Helping-the-Poor programme, discussed in detail in Shihs book (p. 147). For Shih, poverty alleviation strategy is one of the entry points for understanding the Chinese states governing of ethnic minorities and the latters responses to it. The ocial interpretations of poverty take a developmental dimension with the per capita income data providing the measure of poverty levels. The state responses are driven by the goal of ensuring a high economic growth

358

E. Barabantseva

measured by the Gross Domestic Product with the focus on the promotion of market values and competitiveness as the remedies for ethnic minorities backwardness (Shih, p. 13). Shih vividly demonstrates how ocials in China stress reforming the way ethnic people think as one of the solutions to the their poverty. For example, with reference to people in Tujia-Miao Autonomous Prefecture in Western Hunan, their low quality and maladaptation to the progressive force of the market have been identied by the state ocial as the major cause of poverty (Shih, pp. 4778). Another notable quote from the local cadre on the Helping-the-Poor programme eectively summarizes the dominant way of thinking among Chinese policy-makers: the strategy is to use market forces to change their habits that are given to lethargy and to change their customs (Shih, p. 168). Behind the poverty alleviation policies lies the Chinese states ambition to attain the goal of overall modernization which informs and guides the Chinese states approach to development. While this ideal of modernization driven by economic and market values is viewed by the Han entrepreneurs in Herberers study as the standard market practices (p. 174), ethnic minorities associate these practices with the Han domination. This is why state institutions and policies are perceived by the local ethnic minority people as the Han, even when most of the local ocials are ethnic (Herberer, p. 6). All three authors are critical of the ocial discourse linking poverty and ethnicity and emphasize the importance of understanding the earlier and current state policies in generating and deepening the levels of poverty among ethnic minorities (Herberer, p. 13; McCarthy, p. 81; Shih, p. 205). The authors also draw the readers attention to the tension between economic development and preservation of ethnic authenticity and culture. This conict accelerated by the states model of development valuing economic indicators of growth often reduces the value of ethnicity to a cash-earning exercise. Ethnic minorities are pressed to be in line with the rest of the country, and at the same time preserve their exoticism as a symbol of Chinas diversity to satisfy tourist consumption demands. Ethnic minorities discussed in the books engage with the above dilemma in their own unique ways oering alternative ways of being modern intrinsic to their minority status. In contrast to the dominant view in China that ethnic minorities are incapable of successfully engaging in business practices, Herberers research convincingly shows that the Nuosu in Liangshan place entrepreneurialism at the centre of their development strategy and actively embrace the new values proliferated by Chinas market reforms. Nuosu entrepreneurs turn to business activities as their economic strategy for their ethnic group and area, as well as in opposition to the Han dominance. They perceive an aspired entrepreneurial success as a way of asserting their rights and autonomy as the ethnic subjects of the Chinese state. Ethnicity and their cultural values, however, remain detrimental to their business practices. By combining entrepreneurial activities with the strong ethnic identity, they undermine the discursive link between ethnicity and poverty embodied in the conception of ethnic minority in China. Ethnic entrepreneurs thus enact meaningful ways of combining ethnic identity with membership in the Chinese nation. Even when adopting the values proliferated by the state, ethnic minorities signicantly dier from the Chinese state and the Han majority in their interpretations of the meaning of development. The Dai, Bai, and Hui in McCarthys study think of development in more than just economic terms (McCarthy, p. 19).

Downloaded by [Ala Uddin] at 07:56 09 January 2013

Asian Ethnicity

359

The other two authors similarly stress the moral agency of ethnic minorities in contrast to rationalism propagated by the Chinese state since the popularization of Deng Xiaopings black cat, white cat principle. Shih, for example, argues that the states denition of and policies on poverty silence local communities ecological approach to living and their collective identity and action (p. 70). Shih nds that peasants feel secure when they act collectively, rather than individually and emphasizes the need to account for ethnic communities knowledge of ecological perspective on development (p. 70). Similarly, according to Herberers study, Nuosu entrepreneurs stress their social roles and put the interests of their clan above their prot-making (p. 111). The books suggest that ethnic minorities perceive their approaches to development, culture, nature, and their communities as more just, equal, and harmonious than the modernization model advocated by the Chinese state. Ethnicity and modernity Ethnic minorities in the reviewed books oppose the dominant view of ethnicity in China associated with traditionalism, poverty, and backwardness not only through engaging in entrepreneurial practices, but also by creating their own narratives which stress the centrality of their cultures to the Chinese national development. This aspect of the analysis of the Chinese nation contributes an important nuance to the earlier debates on the role of periphery in the construction of Chinese identity. The previous analyses did not suciently examine the place of ethnic minority cultures in producing Chineseness.3 Although the Chinese states ocial interpretations often refer to ethnic minorities as the marginal members of the Chinese nation, ethnic minorities see themselves as the central cultures of the Chinese nation, and even its driving forces. In particular, the cases of the Bai, the Dai, the Hui, the Yi, and the Jing, discussed by McCarthy, Herberer, and Shih are representative of how minorities see themselves as key components of the Chinese nation. Much of these minorities cultural, entrepreneurial, and religious activities are directed at showcasing the contributions of their groups to the development of the Chinese culture overall. For example, Herberer refers to Nuosu scholars and entrepreneurs who perceive the old Yi (Nuosu are ocially included in the Yi minority group) culture as the second most important cultural centre to the formation of the Chinese culture after the traditional central plain culture (p. 189). Their claim of being founders of the Chinese culture unavoidably taps into the state discourse of the plural but united nature of the Chinese nation guaranteeing therefore the recognition and popularization of Yis history (unlike that of the Tibetans and Uyghurs). Nuosu entrepreneurs do not only stress the centrality of Yi to Chinese traditional culture, but, according to Herberer, have internalized the state discourse and see themselves as essential elements to building socialism with Chinese characteristics (Herberer, p. 112). Similarly, the case of the Bai in Yunnan, studied by McCarthy, shows how by uncovering their ancestral links to the eastern Han China, the Bai emphasize their historical contributions to the cultural and economic development of the Chinese Confucian culture and view themselves as not ethnics but paragons of mainstream

3

Downloaded by [Ala Uddin] at 07:56 09 January 2013

See Tu, Cultural China.

360

E. Barabantseva

Chinese rural society (McCarthy, pp. 1415). A non-existent ethnic group before the 1950s, the Bai negotiate their place within the Chinese culture by emphasizing their Chineseness rather than dierence (McCarthy, p. 101). Indeed, in the pre-communist period the Bai did not operate with ethnic categories, but called themselves minjia or civilian households and were actively involved in trade and other activities, such as setting the musical trends during the Tang dynasty, commonly deemed to be the most cosmopolitan of Chinas imperial epochs. The case of Dai, discussed in McCarthys book, illustrates how some minorities in China contest the dominant interpretations of Chinese modernity and national identity not through re-appropriating the ideas, propagated by the state, but by promoting their own, albeit ocially considered backward, local culture and traditions. While some in China and abroad may remain skeptical about the compatibility of the minority cultures and traditions with Chinas goals of modernization, minorities like Dai transcend these debates by reasserting their own ways of being ethnic, Chinese, and modern beyond the restrictive classications and stereotypes (McCarthy, p. 99). By taking on the cultural and religious values of Buddhism, which in the eyes of the local ocials pose obstacles for Dai development eorts, minorities come up with their own formulations of what constitutes a modern Chinese citizen cutting through the heart of the debate on what makes Chinese and what does not.4 Through their religious and cultural practices the Dai problematize the meaning of Chineseness and carve out their own place within the modernizing Chinese society. One of Shihs numerous case studies refers to a dierent way of a minority group stressing their place and role in the Chinese nation. The Jing in Guangxi Autonomous Region linguistically and ethnically identify themselves closely to the Jing ethnic group in Vietnam. However, for the Jing in China their membership in the Chinese nation provides grounds for them to feel superior to the Jing in Vietnam who are in their eyes are a less developed group by a mere virtue of not being part of the Chinese state. In other words, for Chinese Jing being part of Chinas sovereignty serves as a source of pride and distinction from the Vietnamese Jing. While the majority of previous research stressed the role of the Han majority as a reference point for minority identication in China, Shihs analysis shows how this process may occur in relation to an ethnic group across the state border. The case of Muslim Hui, studied by McCarthy, is similarly indicative of how minorities reconcile their ethnicity and membership in the Chinese nation in the attempt to formulate their own versions of modernity. McCarthy analyses religious and cultural revival among the Hui claiming a distinct place within the Chinese nation. To contest the prevailing ocial view of the Hui as rebellious and criminal, the Hui in Yunnan engage in the interpretation of the state-pronounced ideals of modernization and development where their ethnicity and religion are central to these interpretations. It manifests in their particular view of modernization and minority development. Learning Arabic and studying the Koran are their responses to the states call to minority development (p. 158). Although many Hui accept the state-formulated view on the role of science, state education, and economic development in Chinas modernization, they reverse the states prevalent thinking to emphasize the modern character of the Hui culture and religion. They look to the commercial successes of the Hui in pre-Communist China and their extensive trade

4

Downloaded by [Ala Uddin] at 07:56 09 January 2013

Blum, Margins and Centers, 1298.

Asian Ethnicity

361

network linking China with Southeast Asia and stress the scientic basis of Islam to argue that Islam practice is favorable to market economy (McCarthy, pp. 159160). By doing this, the Hui present themselves as the civilizers of the Chinese society undermining the ocial view of Chinas cultural core around the central plain as the civilizing force for the peripheries. Conclusion The reviewed three books make important contributions to the existing perspectives on Chinas ethnic minorities not least for their new rich ethnographies and research ndings. One of their major inputs is the exploration of the big questions on Chinese national identity, citizenship, and modernity from the perspective of ethnic minorities. Ethnic subjects of the Chinese state here are central to the production of Chineseness. While the books recognize the role of the state in articulating ethnicity, autonomy of ethnic minorities is stressed through the recognition of their statuses as the ethnic citizens of the Chinese state. The reader meets ethnic entrepreneurs, cultural activists, artists, poets, teachers, and peasants who see themselves central to the development and prosperity of the Chinese nation. These people work within the existing system and serve as motors of change and development in their local areas. The modalities of change are informed by these peoples particular interpretations of their ethnicities and mobilization of their attributes. Nevertheless, the studies remain critical of Chinas limited autonomous system and minority rights. The authors, Shih in particular, question the Chinese states emphasis on the rights of the autonomous areas over the rights of the people and communities inhabiting the areas. Ethnic status subordinate to the states unity is synonymous with the states stability and preservation of the ruling government. In other words, the autonomous system does not allow ethnic minorities to question the status quo of the political, social, and cultural order of the Chinese state. This is however not the reason to silence the eorts of ethnic minorities living with the above restrictions to nd their own meaningful ways to express their identities and fulll their aspirations. Herberer, McCarthy, and Shih speak out for these people. References

Blum, Susan. Margins and Centers: A Decade of Publishing on Chinas Ethnic Minorities. The Journal for Asian Studies 61, no. 4 (2002):1287310. Tu, Weiming. Cultural China: the Periphery as the Center. Daedalus 120, no. 2 (1991): 132. Wong, Edward. Theme Parks Give Chinese a Peak at Life for Minorities The New York Times, 24 February, 2010. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res9804E2D9103 DF937A15751C0A9669D8B63.

Downloaded by [Ala Uddin] at 07:56 09 January 2013

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Power of TechnologyDocument21 pagesPower of TechnologyAnthriqueNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Education in Bangladesh - The Vision For 2025Document14 pagesEducation in Bangladesh - The Vision For 2025AnthriqueNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Product Catolgue CXWC PDFDocument3 pagesProduct Catolgue CXWC PDFAnthriqueNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Asean & Saarc FrameworksDocument19 pagesAsean & Saarc FrameworksAnthriqueNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Time Series Data On ASI 1998-99 To 2007-08Document975 pagesTime Series Data On ASI 1998-99 To 2007-08AnthriqueNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Life As A Dalit: Views From The Bottom On Caste in India: Author Approval FormDocument1 pageLife As A Dalit: Views From The Bottom On Caste in India: Author Approval FormAnthriqueNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Fee Structure For Ph.D. Program: Shri Venkateshwara University Gajraula, Amroha (U.P.)Document1 pageFee Structure For Ph.D. Program: Shri Venkateshwara University Gajraula, Amroha (U.P.)AnthriqueNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- ESO13-25 Concept of Function - Radcliffe-BrownDocument12 pagesESO13-25 Concept of Function - Radcliffe-BrownakshatgargmoderniteNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Internet Data Plan: 3G Prepaid BroadbandDocument4 pagesInternet Data Plan: 3G Prepaid BroadbandAnthriqueNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- 13082013mcom Iv SemDocument0 pages13082013mcom Iv SemAnthriqueNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Emergency Case StudyDocument230 pagesEmergency Case StudyAnthrique100% (1)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Feminist Terrains in Legal DomainsDocument6 pagesFeminist Terrains in Legal DomainsAnthriqueNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- 3 Meanings of KnowledgeDocument3 pages3 Meanings of KnowledgeAnthriqueNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- ESO13-22 Concept of Culture and Function-MalinowskiDocument21 pagesESO13-22 Concept of Culture and Function-MalinowskiakshatgargmoderniteNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Post Structuralism and Post Modernism: Unit 31Document11 pagesPost Structuralism and Post Modernism: Unit 31AnthriqueNo ratings yet

- Unit - 29Document16 pagesUnit - 29AnthriqueNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Unit 5Document14 pagesUnit 5AnthriqueNo ratings yet

- Human Values Vis A Vis Social JusticeDocument23 pagesHuman Values Vis A Vis Social Justiceyesha rodasNo ratings yet

- A Democratic Dilemma System Effectiveness Versus Citizen ParticipationDocument13 pagesA Democratic Dilemma System Effectiveness Versus Citizen ParticipationDanfNo ratings yet

- UrbTop 149172-Layout1Document11 pagesUrbTop 149172-Layout1Daniel Dent MurguiNo ratings yet

- Colin Crouch Commercialisation or CitizenshipDocument86 pagesColin Crouch Commercialisation or CitizenshipEsteban AriasNo ratings yet

- Module 7 - Tax ExercisesDocument3 pagesModule 7 - Tax ExercisesjessafesalazarNo ratings yet

- Unlawful Request VDocument3 pagesUnlawful Request VBEAU CHARLES QUINTONNo ratings yet

- Ethiopian Grade 11 Civics and Ethical Education Student Textbook PDFDocument148 pagesEthiopian Grade 11 Civics and Ethical Education Student Textbook PDFekram81% (74)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Vocabulary List - Roman Government and Social StructureDocument1 pageVocabulary List - Roman Government and Social StructureIvonne Stephanie Cano RamosNo ratings yet

- Rousseau - ''Discourse On Political Economy''Document43 pagesRousseau - ''Discourse On Political Economy''Giordano BrunoNo ratings yet

- Visa Application Form: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of ThailandDocument1 pageVisa Application Form: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of ThailandBenno TexNo ratings yet

- Information Form: Maldives Islamic BankDocument5 pagesInformation Form: Maldives Islamic BankyrafeeuNo ratings yet

- Angat vs. Republic G.R. No. 132244. September 14, 1999Document2 pagesAngat vs. Republic G.R. No. 132244. September 14, 1999Elaine Belle OgayonNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- HDB InfoWEB Printer Friendly Page 152113417Document1 pageHDB InfoWEB Printer Friendly Page 152113417AThaddeusAntonioNo ratings yet

- LLB 3Y 1st Sem Constitutional Final EnglishDocument40 pagesLLB 3Y 1st Sem Constitutional Final EnglishshaivalNo ratings yet

- Unity Dow V Attorney General of Botswana 1992Document2 pagesUnity Dow V Attorney General of Botswana 1992Shathani Majingo100% (1)

- Grade 9 Civic Short NoteDocument23 pagesGrade 9 Civic Short Noteynebeb zelalemNo ratings yet

- GRADE 7 Social Studies QuestionsDocument11 pagesGRADE 7 Social Studies QuestionsDenise DennisNo ratings yet

- The Liberty Reader (By David Miller, 2006)Document287 pagesThe Liberty Reader (By David Miller, 2006)Fanejeg100% (2)

- Free Patent Act-IRRDocument11 pagesFree Patent Act-IRRMifflin UwuNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Lesson 10Document6 pagesLesson 10gjdb01273No ratings yet

- John Keane Civil Society and The StateDocument63 pagesJohn Keane Civil Society and The StateLee ThachNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument132 pagesUntitledTanvi DangeNo ratings yet

- Case Digest Basic Legal Ethics Subject IN RE: FLORENCIO MALLARE, Respondent (A.M. No. 533, 12 September 1974)Document2 pagesCase Digest Basic Legal Ethics Subject IN RE: FLORENCIO MALLARE, Respondent (A.M. No. 533, 12 September 1974)Grandeur P. G. GuerreroNo ratings yet

- Types of VisaDocument1 pageTypes of VisaDaniel Kotricke100% (3)

- Tecson and Desiderio, Jr. vs. COMELEC 424 SCRA 277, GR 161434 (March 3, 2004)Document7 pagesTecson and Desiderio, Jr. vs. COMELEC 424 SCRA 277, GR 161434 (March 3, 2004)Lu CasNo ratings yet

- Role of TeacherDocument21 pagesRole of TeacherSri KrishnaNo ratings yet

- The Social Studies Curriculum Purposes P PDFDocument432 pagesThe Social Studies Curriculum Purposes P PDFProyectos TICNo ratings yet

- Lesson 26Document36 pagesLesson 26Arnel BilangonNo ratings yet

- Gallie (1955)Document33 pagesGallie (1955)shizogulaschNo ratings yet

- Frivaldo V COMELECDocument72 pagesFrivaldo V COMELECAU SLNo ratings yet

- Prisoners of Geography: Ten Maps That Explain Everything About the WorldFrom EverandPrisoners of Geography: Ten Maps That Explain Everything About the WorldRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1146)

- The Unprotected Class: How Anti-White Racism Is Tearing America ApartFrom EverandThe Unprotected Class: How Anti-White Racism Is Tearing America ApartRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- How States Think: The Rationality of Foreign PolicyFrom EverandHow States Think: The Rationality of Foreign PolicyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (7)