Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Literature and Theory 3 - Adrene Freeda

Uploaded by

john_lonerOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Literature and Theory 3 - Adrene Freeda

Uploaded by

john_lonerCopyright:

Available Formats

Literary Paritantra (Systems) Vol 1 Nos 1 & 2 Basant (Spring) 2009, 77-82

77

The Postmodern Cultural Matrix and the Post-industrial Social Structure: Don DeLillos White Noise

Adrene Freeda Dcruz

Department of Humanities and Social Sciences Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur, India

Abstract

Don DeLillos White Noise (1984) maps the contours of the postmodern consumer society that is characterized by an abundance of mass produced objects. Locating the events in a technologically oriented post-industrial environment, White Noise critiques the traditional notions of origin and monolithic truth posited in the representation of any event. In doing so, DeLillo effectively underscores the fruition of the postmodern aesthetics of copies without original. Besides, the novel highlights some of the salient features of the consumer society in the light of Jean Baudrillards theoretical insights. Representing such a postmodern society saturated by media events, White Noise enumerates the workings of technocapitalism as the technologically driven events in the novel construct a new social order in the post-industrial town of Blacksmith. In spelling out the postmodern phenomenon of copies devoid of originals, this essay focuses on DeLillos critique of commodity culture on ecological as well as ethical grounds.

Set in the post-industrial era, Don DeLillos White Noise (1984), captures the ethos of the postmodern consumer society by specifically analyzing the technologically oriented environment. While in the first phase of his writing careerfrom Americana to The NamesDeLillo explores themes such as baseball as a national game, the function of names, the indeterminacy of language, and the critique of historical accuracy, in White Noise the novelist deals with the upcoming consumer society in a small town named Blacksmith where technological expertise and the image of overabundance of objects make up the structure and fabric of the society. This essay examines the mushrooming consumer society of Blacksmith by analyzing how DeLillo blends the post- industrial consumer society with the postmodernist aesthetics of copies without original. Far from being a mere commercial enterprise, supermarkets in White Noise are the centers of American magic and dread (19) and play a prominent role in articulating some of the principal characteristics of the postmodern consumer society in general. DeLillo designates the consumers as masses who, guided by the flickering images on the screen, throng the object centered supermarkets. In the wake of technological boom, consumers in White Noise adorn the object oriented outlook, and this inclination links the question of consumerism in the novel to Jean Baudrillards analysis of consumer behaviour in The Consumer Society. For Baudrillard, the quintessential feature of postmodern consumer society is that the humans of the age of affluence are surrounded not so much by other human beings, as they were in previous ages, but by objects (25). Besides, with their dazzling hedgerows (167) supermarkets metaphorically stand for the postmodernist notion of abundance:

ISSN 0974- 7915 Print, ISSN 0974-7923 Online, http://www.literaryparitantra.org Copyright 2009 Dayalbagh Educational Institute

78

Adrene Freeda Dcruz

the mass and variety of our purchases, in the sheer plentitude those familiar package designs and vivid lettering, the giant sizes, the family bargain packs with day-Glo sale stickers, in the sense of replenishment we felt, the sense of well-being, the security and contentment these products brought to some snug home in our souls. (20) The plentitude is the result of the mass production of merchandise, signaling a movement from industrial production to the postmodern industry of mass production. In other words, the industrialization gave way to the post-industrial mode of production where exact replicas delegitimize the notion of an original product. Mike Featherstone blends the post-industrial and the postmodern concerns in Consumer Culture and Postmodernism and emphasizes that the world of goods and their principles of structuration are central to the understanding of contemporary society (84). In such a mode of production, one product resembles the other so meticulously that they cannot be distinguished from each other. DeLillo calls this specific phenomenon seen in supermarkets as a brilliant event and a spectacle (3). Also, the reference to the supermarkets brings out the significance of the white in White Noise. Looking at the products packaged for mass consumption, bought by an ex-sportswriter Murray Jay Siskind, the protagonist Jack Gladney remarks: His basket held generic food and drink, nonbrand items in plain white packages with simples labeling. There was a white can labeled CANNED PEACHES. There was a white package of bacon without plastic window for viewing a representative slice. A jar of roasted nuts had a white wrapper bearing the words IRREGULAR PEANUTS . . . . Everything is white (18) The significance of white coupled with the noise illustrates the background of supermarkets. In the postindustrial milieu, the supermarkets are flooded with items that are imperceptible, and instead of euphony what characterizes supermarkets is cacophony. Significantly, the white and noise together forcefully build up the picture of supermarkets and provide the point of intersection between the post-industrial object driven society and the postmodern ethos of copies without originals. As an inevitable factor trailing alongside the consumer society, capitalism in DeLillos White Noise merges the escalating need for consumption with the capitalist system. The capitalist mode of production flourishes in the post- industrial set up and offers the masses new vistas of development. In the novel the technological rumble stands out when consumerism and capitalism make life mechanical, promoting overindulgence in the apparent autonomy offered by machines. Significantly, Laura Barrett comments on the objectification of life during the post-industrial period: far from it roots in Protestantism and the western, White Noise presents a world in which individuality is replaced by media role models and God is replaced by an ATM (101). In White Noise the Automated Teller Machine, with the networks, the circuits, the streams, the harmonies, offers Jack Gladney a pleasing interaction (46); it is a system that rules the lives of the people in Blacksmith town and dons animate characteristics: I [Jack Gladney] went to the automated teller machine to check my balance. I inserted my card, entered my secret code, tapped out my request. The figure on the screen roughly corresponded to my independent estimate, feebly arrived at after long searches through documents, tormented arithmetic. Waves of relief and gratitude flowed over me. The system had blessed my life. I felt its support and approval. (46) Additionally, infused with technological prowess, the appliances like the dishwasher, the refrigerator, the helicopters throbbed, a label usually given to the functioning of the human heart. Advertisements, transmitted through the network of little buzzing dots that make up the picture pattern, (51) inevitably

ISSN 0974- 7915 Print, ISSN 0974-7923 Online, http://www.literaryparitantra.org Copyright 2009 Dayalbagh Educational Institute

Literary Paritantra (Systems)

79

function through coded messages that seeps into the minds of millions of consumers. DeLillo illustrates the overwhelming influence of advertisements through the example of the commercial on Coke:

Look at the wealth of data concealed in the gird [Television], in the bright packaging, the jingles, the slice-of-life commercials, the products hurtling out of darkness, the coded messages and endless repetitions, like chants, like mantras. Coke is it, Coke is it, Coke is it. The medium practically overflows with sacred formulas. (51) Understood as the mass-producers of culture, (50) objects, such as television, weave a cultural matrix that captivates the masses so much so that the masses exhibit endless, insatiable thirst for consuming electronic images. Also, the postmodern cultural milieu, of which Jack Gladney and his family are part of, relives every event through the visual consumption of images. Douglas Keesey notes that in the household of Gladney, the familys contact with the real world is interrupted by media representations of that world, televison shows, radio programs, tabloid stories, enclosed shopping malls and processed foods that have taken the place of nature (135). Television is here a vital constituent of life and is known for its incessant bombardment of information (66). In White Noise, spatial congestion takes a queer turn in the consumers unappeasable craving for visual images. As evidenced by DeLillo, the only two places that exist for people belonging to such a state are where they live and their TV set (66). Frank Lentricchia in Tales of the Electronic Tribe extracts an episode from DeLillos Americana in order to pair the advent of television with the arrival of Americans on the Mayflower: If television is the quintessential technological constituent of the postmodern temper (so it goes), and postmodernism the ethos of the electronic society, then with twenty years of hindsight on DeLillos book we can say that what actually came over on the Mayflower was postmodernism itself, the founding piece of Americans (88). As DeLillo rightly points out in Americana, the booming of America and the technological growth go hand in hand in creating a consumer ridden post-industrial technocapitalist environment in which the medium of television hold a unique position through the act of ensnaring consumers. In White Noise, it stands to reason why violence, electronically transmitted, is always an act of celebration. Alfonse Stompanato, the chairman of the College-on-the-Hill in the novel, offers a valid observation of this effect: If a thing happens on television, we have every right to find it fascinating, whatever it is (66). Also, the unending desire for violence, remarks Murray Siskind, stems from movies which offer visual satisfaction for the consumers of the image. For instance, car crashes on television, rendered as the suicide wish of technology (217), capture the audience, and making them enjoy watching the same spectacle ad infinitum. The movies, in White Noise, organize a platform for the act of violence to turn celebratory: Its [a car crash in a movie] a celebration. These are days of secular optimism, of self-celebration. We will improve, prosper, perfect ourselves. Watch any car crash in any American movie. It is a highspirited moment like old-fashioned stunt flying, walking on wings (218). This particular instance is reminiscent of DeLillos latest novel Falling Man in which the spectators relive the collapse of the World Trade Center through David Janiaks terror inducing performance: There was the awful openness of it [Janick dangling on a rope], something wed not seen, the single falling figure that trails a collective dread, body come down among us all (DeLillo, 2007, p. 33). Likewise, in the town of Blacksmith these instances bring out the celebration of dread inducing acts in different media. The image of Blacksmith, with the unique art of forging that creates dread, unmistakably calls up associations with William Blakes The Tyger. Figuratively, Blacksmith in White Noise suggests the act of

ISSN 0974- 7915 Print, ISSN 0974-7923 Online, http://www.literaryparitantra.org Copyright 2009 Dayalbagh Educational Institute

80

Adrene Freeda Dcruz

forging; technology acts as the smith that forges human lives. As an inevitable part of every household in Blacksmith, the television set forms an inseparable part of the consumer society in formulating and reformulating spectacles of magic inducing dread that in turn cast an unmistakable influence on the minds of the consumers, especially the children who belong to the town of Blacksmith. For DeLillo, technology, coupled with capitalism, also result in the daily seeping falsehearted death (22) and perhaps the most fitting illustration of the link between the consumer society and capitalism in the novel is the existence of the pill named Dylar. Dylar, a multinational project whose resident organizational genius is Willie Mink, tricks the consumers into falsity and offers them tablets (Dylar) to ward off the fear of impending death. In the novel, Dylar has protean implications; Dr. Hookstratten designates it as an island in the Persian Gulf, one of those oil terminals crucial to the survival of the West (180). But for Jack Gladney, Dylar is the name of a pill that his wife Babette consumes to fend off death. By consuming the pill, Babette, quite contrary to the capitalist assurance through advertisements of eternal oblivion of death, experiences gradual hair loss and slips into a rapid corrosion of memory. Unknown to anybody, Babette becomes a scapegoat in the hands of the capitalist enterprise. Instead of living up to the promise of removing the patients fear of death, the multinational giants unethically utilize the patients to experiment their products. As evidenced in White Noise, the merging of technology with the capitalistic projects builds up false concerns of human well being, upholding lucrative reasons at the cost of the deteriorating human lives. To depict the state of decay in the post-industrial era, DeLillo brilliantly employs the image of rats. Rats are the common denominator of decay in the fictional corpus of DeLillo, especially in Cosmopolis. Set against the background of technocapitalism, Cosmopolis brings out the seamy side of the interaction between technology and capitalism (Cosmopolis 23) with reference to rats. A rat became the unit of currency, a line from the Polish poet Zbigniew Herberts poem Report from the Besieged City, serves as the epigraph of Cosmopolis. If Herberts poem argues that the unit of exchange (money) dictates human life, in the technological age of DeLillo human beings obey the orders of technology. In White Noise rats test for things that humans can catch, so it means we get the same diseases, rats and humans (124). DeLillo gives a metaphorical twist to this scientific phenomenon by stating that in the post-industrial era experiments take place not on rats but on human beings like Babette who turn prey to institutions such as capitalism. Significantly, the pill is referred to as a white tablet that is more or less flying-saucer-shaped, a streamlined disk with the tiniest of holes at one end (184). Tinged with an unconventional flair, the color white signifies fraudulence, as strictly opposed to innocence, and the novel in a subtle manner critiques the advertisements that lure the consumers into hollow promises that seek to give credibility to publicized products. Aptly rendered, DeLillo names Dylar as the technology with a human face (211) and focuses on concerns such as how inevitable technology is for human existence and how technology often fabricates the lives of human beings for economic motives. In White Noise, the prevalence of commodity culture is further heightened with reference to media related events and the absence of the original in the episode of THE MOST PHOTOGRAPHED BARN IN AMERICA (12). Resembling Jean Baudrillards fourth stage of simulation where sign has no relation to any reality, this barn in Farmington is available only through copies for which there is no original. Jack Gladney and Murray Siskind are part of the crowd that throng to this tourist spot in America and constitute what DeLillo terms as a collective perception (12). The collective identity that is always in a flux is the hallmark of the consumer era where the barn exists not in the individual perception but in the collective one: We see only what the others see. The thousands who were here in the past, those who will come in the future. Weve agreed to be part of a collective perception (12). The barn continues to exist as a sign among many other signs and acquires meaning only in relation to the collective observation. Kenneth Millard comments on this as an exclusive

ISSN 0974- 7915 Print, ISSN 0974-7923 Online, http://www.literaryparitantra.org Copyright 2009 Dayalbagh Educational Institute

Literary Paritantra (Systems)

81

postmodern phenomenon: the barn disappears altogether and becomes irrelevant to the real experience, which is one of mediating not the barn but other acts of meditation; the referent has gone, and contemporary Americans can only record representations of the barns exclusively representational status (126). Murray in the novel explains that once youve seen the signs about the barn, it becomes impossible to see the barn (12). In other words, the barn functions like words, as a set of signifiers that have meaning only in relation to other words in the signifying chain. Additionally, the long lost bucolic, pastoral illustration of barn is available only through images, namely, photographs, postcards and slides; it is the (re)presentation of an image with no corresponding (real)ity. Furthermore, the barn constitutes a metapicture, taking pictures of taking pictures (13), and metaphorically translates the postmodern perception of the existence of copies with no equivalent reality. Thus, DeLillo critiques the veracity of questions related to the depiction of reality and monolithic truths in media representation of events. Although ecocide in the postmodern consumer society is an abiding concern in White Noise, the notion of simulation surrounding the issue of ecological imbalance gets highlighted too. Technological growth adds to the panoramic vision of life, yet the ecology grossly suffers from technological exploitation. In White Noise the ecological inequity is caused due to the release of Nyodene Derivative, collectively titled the airborne toxic event. Nyodene D. is a whole bunch of things thrown together that are byproducts of the manufacture of insecticide (131) and Gladneys contact with the toxic material is explained by the technician in SIMVAC (simulated evacuation) to have lethal effects. The toxic waste, released into the air through the vaporized chemicals forming a black billowing cloud (113), adversely affects human memory and the exposure to the chemical brings about convulsion, coma, and miscarriage. Ecologically speaking, the Nyodene operation, with the aid of technological inputs, unethically tests on the humans that which was formerly done on rats, the effect being that: Once it [Nyodene Derivative] seeps into the soil, it has a life span of forty years. This is no longer than a lot of people. After five years youll notice various kinds of fungi appearing between your regular windows and storm windows as well as in your clothes and food. After ten years your screens will turn rusty and begin to pit and rot . . . and trauma to pets. After twenty years youll probably have to seal yourself in the attic and just wait and see. I guess theres a lesson in all this. Get to know your chemicals (131). Just like the billowing black cloud has a haze of unknown origin (206), the origin and effect of the toxic event linger uncertain. Although the event appears real, the word simulated in simulated evacuation tends to blur the line between what is real and unreal. The effects of the toxic event leave Gladneys daughter Steffie hazy as to whether her palms had been truly sweaty or whether shed simply imagined a sense of wetness (126). As a symptom of Nyodene contamination, Dj vu, the false illusion of reality sets in. Psychologically speaking, Dj vu is a vague condition in which things seem to have been already experienced but without authentic origins. This condition causes the supposedly real event to be overshadowed by the illusion of the real. Like Babette being a scapegoat at the hands of the capitalism, which produces the pill Dylar, the external exposure to the chemicals in the airborne toxic event causes in Jack Gladney a fear that death is in the air (151). Gladneys son Heinrich, although a boy of fourteen who showed maturity at a very tender age, believes that there was something ominous in the modern sunset (61). The glory of the setting sun, one of the exquisite natural scenery enjoyed by all ages, loses its aura in the town of Blacksmith owing to the commercialized outlook. For Gladney the postmodern sunset, rich in romantic imagery (227) resembled the sun, going down like a ship in a burning sea (227). The reproduction of the sunset in various digitalized forms produces copies more real than the original to such an extent that it becomes all the more difficult to

ISSN 0974- 7915 Print, ISSN 0974-7923 Online, http://www.literaryparitantra.org Copyright 2009 Dayalbagh Educational Institute

82

Adrene Freeda Dcruz

distinguish the original and the copy. In the postmodern age, the progression of digital minutes (224) makes the instruments of intrusion [camera] (162) endlessly reproduce natural beauty as representations. Commenting on the representational matrix of the post-industrial era, Leonard Wilcox observes that in White Noise DeLillos protagonist Jack Gladney confronts a new order in which life is increasingly lived in a world of simulacra, where images and electronic representations replace direct experience (346). In short, while examining the post-industrial town of Blacksmith, White Noise develops a critique of the ecological imbalance caused by the unethical use of technological expertise and subtly enforces the vital postmodern sensibility of the myriad representations of reality through technological lens. Articulating the concerns that surround the post-industrial consumer society, Don DeLillos White Noise occupies a unique representational status in capturing the postmodern aesthetics within the technocapitalist environment. In White Noise, the post-industrial town of Blacksmith remains a microcosm of the contemporary technologically driven consumer society. A postmodern sensibility permeates the events in White Noise and states a sustained critique of the conventional beliefs that surround the concept of original and the authentic representation of reality. The budding consumer society, that reconstructs a new social order where technology works concurrently with the ideals of capitalism, draws attention to certain ethical concerns such as ecocide and inhuman practices that result in the dilapidated human condition. To conclude, DeLillos White Noise underscores the postmodern dynamics of simulation by focusing on the socio-cultural framework of Blacksmith where the electronic recreation of images reproduces the postmodern aesthetics of copies without original.

Works Cited

Barrett, Laura. How the Dead Speak to the Living: Intertextuality and the Postmodern Sublime in White Noise. Journal of Modern Literature. 25.2 (2001-2): 97-113. Baudrillard Jean. The Consumer Society: Myths and Structures. Trans. Chris Turner. London: Sage Publications, 1998. DeLillo, Don. Cosmopolis. London: Picador, 2004. ------------. Falling Man. New York: Scribner, 2007. ------------. White Noise. New York: Viking, 1985. Featherstone, Mike. Consumer Culture and Postmodernism. London: Sage Publications, 2005. Keesey, Douglas. Don DeLillo. New York: Twayne Publishers, 1993. Lentricchia, Frank. New Essays on White Noise. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991. Millard, Kenneth. Contemporary American Fiction: An Introduction to American Fiction Since 1970. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. Wilcox, Leonard. Baudrillard, DeLillos White Noise, and the End of Heroic Narrative. Contemporary Literature. 32.3 (1991): 346-365.

Notes on the Contributor

Adrene Freeda Dcruz is a Ph.D candidate at the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology, Kanpur. She is completing her dissertation on Modes of Excess in Don DeLillos Novels.

ISSN 0974- 7915 Print, ISSN 0974-7923 Online, http://www.literaryparitantra.org Copyright 2009 Dayalbagh Educational Institute

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Hazardous Materials Managment HandbookDocument85 pagesHazardous Materials Managment Handbookhuntercapoeira100% (2)

- Marine Painting HandbookDocument212 pagesMarine Painting HandbookVallabh Vishwanath Desai100% (3)

- Camp InspectionDocument76 pagesCamp InspectionshijadNo ratings yet

- MSDS Benzene PDFDocument6 pagesMSDS Benzene PDFPiyu SyahputraNo ratings yet

- Albafix ECODocument10 pagesAlbafix ECOTrinhTruongNo ratings yet

- 1, Woodburn Park, Kolkata - 700 020 PHONE: (033) 2283-5157, TELEFAX: (033) 2283-5082 Website: WWW - Wbnsou.ac - inDocument6 pages1, Woodburn Park, Kolkata - 700 020 PHONE: (033) 2283-5157, TELEFAX: (033) 2283-5082 Website: WWW - Wbnsou.ac - injohn_lonerNo ratings yet

- James Carey - Communication As Culture: Essays On Media and SocietyDocument6 pagesJames Carey - Communication As Culture: Essays On Media and Societyjohn_lonerNo ratings yet

- Notice Regarding Registration SlipDocument1 pageNotice Regarding Registration Slipjohn_lonerNo ratings yet

- Reg 2013169 Not WebpageDocument1 pageReg 2013169 Not Webpagejohn_lonerNo ratings yet

- Announcement Admssion Int Mphil PHD Direct PHD 2013-141Document4 pagesAnnouncement Admssion Int Mphil PHD Direct PHD 2013-141john_lonerNo ratings yet

- Called For Interview CMS APDocument1 pageCalled For Interview CMS APjohn_lonerNo ratings yet

- The Public Relations Handbook: Alison TheakerDocument3 pagesThe Public Relations Handbook: Alison Theakerjohn_lonerNo ratings yet

- Modernization and Post Modernization PDFDocument14 pagesModernization and Post Modernization PDFRicardo ForeroNo ratings yet

- Admission To Ph.D. Programme (July, 2013)Document1 pageAdmission To Ph.D. Programme (July, 2013)john_lonerNo ratings yet

- 4Document1 page4john_lonerNo ratings yet

- Supplementary List: Jadavpur University Faculty of Arts KOLKATA - 700 032Document1 pageSupplementary List: Jadavpur University Faculty of Arts KOLKATA - 700 032john_lonerNo ratings yet

- Called For Interview CMS APDocument1 pageCalled For Interview CMS APjohn_lonerNo ratings yet

- Called For Interview CMS APDocument1 pageCalled For Interview CMS APjohn_lonerNo ratings yet

- Baking Soda Chemistry LessonDocument2 pagesBaking Soda Chemistry Lessonjohn_lonerNo ratings yet

- Registration of Hindu Marriage Application FormDocument2 pagesRegistration of Hindu Marriage Application Formjohn_lonerNo ratings yet

- Shikshayatan College Admission Dates BA BSc Direct Walk-in July 2013Document1 pageShikshayatan College Admission Dates BA BSc Direct Walk-in July 2013john_lonerNo ratings yet

- PHD Corrigendum Int02Document2 pagesPHD Corrigendum Int02john_lonerNo ratings yet

- Wbcsccorrigendumadvt1 2012DTD10 05 13 - 2Document1 pageWbcsccorrigendumadvt1 2012DTD10 05 13 - 2john_lonerNo ratings yet

- 4Document1 page4john_lonerNo ratings yet

- HaigDocument25 pagesHaigjohn_lonerNo ratings yet

- Shri Shikshayatan College: First Merit List - 2013Document1 pageShri Shikshayatan College: First Merit List - 2013john_lonerNo ratings yet

- B.A (English) Gen WB BDocument1 pageB.A (English) Gen WB Bjohn_lonerNo ratings yet

- Visva-Bharati Santiniketan Recruiting For Various PostsDocument10 pagesVisva-Bharati Santiniketan Recruiting For Various PostsCareerNotifications.com100% (1)

- Shikshayatan College Admission Dates BA BSc Direct Walk-in July 2013Document1 pageShikshayatan College Admission Dates BA BSc Direct Walk-in July 2013john_lonerNo ratings yet

- Supplementary List: Jadavpur University Faculty of Arts KOLKATA - 700 032Document1 pageSupplementary List: Jadavpur University Faculty of Arts KOLKATA - 700 032john_lonerNo ratings yet

- Advt 05 2013Document5 pagesAdvt 05 2013john_lonerNo ratings yet

- Shri Shikshayatan College: First Merit List - 2013Document1 pageShri Shikshayatan College: First Merit List - 2013john_lonerNo ratings yet

- Wbcsccorrigendumadvt1 2012DTD10 05 13 - 2Document1 pageWbcsccorrigendumadvt1 2012DTD10 05 13 - 2john_lonerNo ratings yet

- How Pollutants Affect Organism PhysiologyDocument37 pagesHow Pollutants Affect Organism PhysiologylinakristianaNo ratings yet

- 472 - Fusilade MaxDocument10 pages472 - Fusilade MaxPramod PeethambaranNo ratings yet

- Aquabreak PX: Catalogue Number: 575613 - 575605 Version No: 9.12Document11 pagesAquabreak PX: Catalogue Number: 575613 - 575605 Version No: 9.12Sergey KalovskyNo ratings yet

- Shell Spirax ASX-R 75W-90 MSDSDocument7 pagesShell Spirax ASX-R 75W-90 MSDSAnonymous LfeGI2hMNo ratings yet

- Shell Omala Oil F 320 Safety Data SheetDocument7 pagesShell Omala Oil F 320 Safety Data SheetIsabela BoceanuNo ratings yet

- Clorox - Hydrogen Proxide - MSD - SDSD11585Document9 pagesClorox - Hydrogen Proxide - MSD - SDSD11585Agung PriyantoNo ratings yet

- Antiseptic Disinfectant Smart Hygine: Safety Data SheetDocument4 pagesAntiseptic Disinfectant Smart Hygine: Safety Data Sheetaldi_dudulNo ratings yet

- Safety Data Sheet (SDS of RONDO)Document9 pagesSafety Data Sheet (SDS of RONDO)jr-nts ntsNo ratings yet

- Et47617 - SP Arlamol Ps15e-Mbal-Lq - (Ap) - UsensdsDocument7 pagesEt47617 - SP Arlamol Ps15e-Mbal-Lq - (Ap) - UsensdsMohammad BhatNo ratings yet

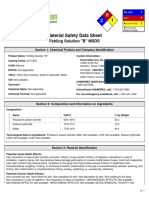

- Fehling Solution "B" MSDS: Section 1: Chemical Product and Company IdentificationDocument6 pagesFehling Solution "B" MSDS: Section 1: Chemical Product and Company IdentificationAnnisaNo ratings yet

- Clariant SDS Genapol O 050 SG Vita India EnglishDocument9 pagesClariant SDS Genapol O 050 SG Vita India EnglishShailendra SinghNo ratings yet

- CELLPACKDocument4 pagesCELLPACKlab pesanggrahanNo ratings yet

- Ammonium HeptamolybdatDocument6 pagesAmmonium HeptamolybdatRega Wahyu AnggrainiNo ratings yet

- 1315-01 Assessment Report PDFDocument88 pages1315-01 Assessment Report PDFbeli_oblak_1No ratings yet

- Construction Project Safe System of Work TemplateDocument16 pagesConstruction Project Safe System of Work Templater2mgt28ssvNo ratings yet

- MSDS - Curran SelulosaDocument7 pagesMSDS - Curran SelulosaRivaldi Ahmad HaedirNo ratings yet

- Material Safty Data Sheet: Product Ref. PS 02 Issue No. 2 Date OCT-2018Document2 pagesMaterial Safty Data Sheet: Product Ref. PS 02 Issue No. 2 Date OCT-2018Redha SabrNo ratings yet

- 0166 BenzeneDocument8 pages0166 BenzeneFirdaus OkeNo ratings yet

- SDS Protan Ventiflex Ducting Material 6298FR and 6698FR v.2.0 - ENGDocument3 pagesSDS Protan Ventiflex Ducting Material 6298FR and 6698FR v.2.0 - ENGTom HightNo ratings yet

- MSDS DylonDocument15 pagesMSDS DylonellaNo ratings yet

- Acetone Safety Data Sheet PDFDocument8 pagesAcetone Safety Data Sheet PDFMarkChenNo ratings yet

- Unilever Australia MSDSDocument5 pagesUnilever Australia MSDSarditNo ratings yet

- Morpholine MSDSDocument7 pagesMorpholine MSDSAlves EdattukaranNo ratings yet

- Hilti Firestop Acrylic Sealant CFS-S ACR CP 606: Safety Data SheetDocument7 pagesHilti Firestop Acrylic Sealant CFS-S ACR CP 606: Safety Data SheetArulNo ratings yet

- ISO 11348-3-BioFixDocument3 pagesISO 11348-3-BioFixamirNo ratings yet