Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Boix 2001

Uploaded by

Diego Ignacio Córdova MolinaOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Boix 2001

Uploaded by

Diego Ignacio Córdova MolinaCopyright:

Available Formats

Democracy, Development, and the Public Sector Author(s): Carles Boix Reviewed work(s): Source: American Journal of Political

Science, Vol. 45, No. 1 (Jan., 2001), pp. 1-17 Published by: Midwest Political Science Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2669356 . Accessed: 19/11/2012 15:19

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Midwest Political Science Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to American Journal of Political Science.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded by the authorized user from 192.168.72.230 on Mon, 19 Nov 2012 15:19:50 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Democracy, Development, andthe Public Sector

CariesBoix

ofChicago University

This articledevelops a model that describes the growth of the public sector as a jointresultof the process of economic developmentand the in place. The politicalinstitutions model is tested using panel data for about sixty fivedeveloping and developed nationsforthe period 195090. Economic modernization leads to of the public sector the growth through two mechanisms: first, the state intervenes to providecertain collectivegoods such as regulatory agencies and infrastructures; second, industrialization and an ageing populationtranslateintohigherdemands in the form fortransfers of unemploymentbenefits, healthinsurance,and the impactof e-copensions. Still, nomicdevelopmentis strongly conditionalon the politicalregimein place as well as on the level of electoral Whereas in a demoparticipation. craticregime,where politiciansrespond to voters'demands, the public sector grows parallelto the structural economic changes associated with coundevelopment,in authoritarian triesthe size of the public sector remainssmall.

wo stylized facts describetheevolution of thepublicsectoracross theworldduringthelast century: first, itssteadygrowth; second, thepresence of persistent cross-national differences in itssize. Excludingwar times, government expenditure remained constant around 10 ofGDP during thenineteenth percent century. Yetafter 1914thesizeofthe In OECD nations, publicsectorexpandeddramatically. totalcurrent public revenue had risento 24 percent of GDP in theearly1950s.Thirty years laterit had stabilized at around44 percent. Amongdeveloping countries, current publicrevenue grew from14 percent ofGDP in 1950to around27 from thelate 1970sonward. percent Despitethesteady ofthepublicsector, growth differences acrossnations have remained In themid-1980s, substantial. publicrevenue rangedfrom lessthan10percent ofGDP in Sierra Leoneand Paraguay to over60 percent in Botswana,Kuwait, Reunion,and Sweden.Cross-national variation has becomeespecially acutein thedeveloping worldovertime.Whereasin the ofpublicrevenue in non-OECD nations early1950sthestandard deviation was 4 percent, bythemid-1980sithad reached15 percent ofGDP. of thepublicsectorin thelastcentury The growth has spawneda vigorous literature on its causes.1Three families of explanations standout. the a of "Demand-side"explanations, conceiving government as provider the growthof the public sectoreitherto social public goods, attribute progressand demographic transformations (Wagner 1883; Wilensky in thepublicand private ratesof productivity 1975) or to different growth sectors(Baumol 1967). "Political"or redistributive theoriesmodel the to social conflict, as an agencythat,responding redistributes government income among citizens (Meltzer and Richards 1981; Esping-Andersen "institutional" modelshave stressed theimpactof different 1990). Finally, structures of government, such as bureaucracies(Niskanen 1971), the of thelegislative branch(Shepsleand Weingast structure 1981) or federalism,on thesize of thepublicsector.

BoixisAssistant Professor ofPolitical TheUniversity ofChicago, Carles Science, 5828S. University Avenue, Chicago, IL 60637(cboix@midway.uchicago.edu). in the1997and 1998AnnualMeetings Previous versions ofthisarticle werepresented inthe oftheAmerican Political Science Association, attheCenter for Advanced Studies and at theConference SocialSciences, Fundacion Juan March, "Spainin Europe: EconomicPerspectives and Challenges" at NewYork University (December1999).I thank thecomments oftheir participants andtheeditorial assistance ofGreg Caldeira andSusan Meyer. Financialsupportof the Centrede Recercaen EconomiaInternacional (Universitat PompeuFabra, Barcelona) andTheOhio State University is acknowledged. 'Forextensive reviews seeLybeck (1988) and Holsey andBorcherding (1997). 2001,Pp. 1-17 Science, Vol.45,No. 1,January American Journal ofPolitical Science Association ?2001 bytheMidwest Political

1

This content downloaded by the authorized user from 192.168.72.230 on Mon, 19 Nov 2012 15:19:50 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CARLES

BOIX

The contemporary research on thecauses of public spending suffers, however, from twofundamental weaknesses: thefirst one,empirical; theother one,strictly theoretical. To date most empiricalstudiesare inconclusive (Altand Chrystal 1983,chapter 8; Lybeck1988;Mueller 1988,chapter17; Holsey and Borcherding 1997). Most scholarsuse limited samples, such as one-country timeseriesanalysis of countries, and focus or a cross-section on singlepolicymeasures.2 Some recent studies havedeveloped pooled time-series cross-sectional samplesfor (most) OECD nations (Pampel and Williamson 1988; Korpi 1989; Hicks and Swank 1992; Huber,Ragin,and Stephens 1993).Although they go a longwayin determiningtheforces behindthegrowth ofthepublicsector, several explanatory factors, such as left-wing rule, and theproportion of old popucorporatism, openness, lation, areso wellcorrelated thatitis impossible to ascertain,first, whichvariableactuallymatters and, second, whatspecific itdoes.Theirfocuson through mechanisms OECD nationslimits their Theirsampleof applicability. advanceddemocraciescan onlyveryweakly testforthe of economicdevelopment, effects the impactof demoand theinfluence cratic(vs.authoritarian) ofan regimes, ofresources. To remedy unequaldistribution theseproblems,thisarticlerelieson a broad sample of developed and developingnations. This sample includes all the forwhichcomparabledata on public revenue countries ofthegeneral areavailable (current receipts) government from1950to 1990.The sampleincludesabout sixty-five withsome countries are OECD members), (twenty-two fluctuations dependingon the timeperiod,and about 2,000observations.3 of the research The inconclusiveness on the growth of the public sectorstemsas well froman inadequate theoreticalspecificationof the currentmodels. "Demand-side" whichrely on theidea that theories, heavily to the(changing) tastes politicians mechanically respond ofthemedianvoter, discount thepotential redistributive

2Forinitialstudieson a limitednumberof cases,see Titmuss (1958),Marshall (1963),Peacock andWiseman (1961). Forinitial cross-sectional studies, see Cutright (1965) and Wilensky (1975) on advanced and developing nations, Jackman (1975) on American states, and Esping-Andersen (1990) and Cameron(1978) on alone. OECD nations 3Rodrik (1996) and Cheibub(1998) haverecently builtbroader samples that encompass developed and developingnations. Rodrik(1996), however, employs publicconsumption as a percentage ofGDP.Thisis too limited a toolto measure thesizeofthe welfare state and provides highly biasedresults (given howimportant is among public consumption developing countries). Cheibub (1998) employs dataon central government, which also measures totalpublic expenditure veryimperfectly (especially forlarge, closedeconomies, whichtendto be decentralized), and focuses only on thetaxcapacity associated with different political regimes.

costsoftaxation. In turn, modelsconcenpurely political thatan unequal distribution trate too muchon theeffect has on thetaxrateto theextent ofresources ofdisregarding how economic developmentaltersthe underlying structure ofpreferences in theelectorate. As a result, they cannot explainwhyper capita income is so well correlatedwiththesize of thepublicsector. To overcomethese deficiencies, I develop a joint model thatintegrates both the impactof economicdevelopment and the underlyingstructureof political choice as follows. Economic development triggers pressuresto enlargethepublic sectorin two ways.First, the processes of urbanization and industrialization generate incentives forthe stateprovisionof certaincollective and skillformation. goods such as infrastructures Secof an industrial ond, both the emergence economyand an ageingpopulationshift theunderlying distribution of in a waythatresults in stronger preferences demandsfor The processof economic developpublic expenditure. mentconstitutes, a necessary but not sufficient however, condition forthe emergenceof a large public sector. who make policy througha political Policy-makers, choose the public sectorthatmatchesthe mechanism, ofthemedianvoter. preferences The identity ofthelatter variesconditional on the electoral in place (as franchise wellas on theextent to whichvoters are mobilized).This variationshapes,in turn,the size of the public sector. Under a democraticregime, politiciansrespondto the demandsof all voters and thepublicsectorgrows parallel to thestructural changesdue to theprocessof develin authoritarian whereall opment.By contrast, systems, or a substantial is excludedfrom part of the electorate the decision-makingprocess, preciselyto avoid the redistributional the size of consequencesof democracy, thepublicsector remains small.

Economic Development andPolitical Regime

ThePolitical Setting

To examinehow economicdevelopment and theunderthe size of the lyingpoliticalsystem jointlydetermine I proceedin two steps.In thissubsection I publicsector, modelthegeneric whichthesize political setting through of the public sectorand hence thetax rateto financeit are decided.To do so, I relyon a model first derivedby Meltzer and Richards (1981), to whichI add theassumption of a general(nonredistributive) demandforpublic investment programs and publicgoods from citizens. In the nextsubsection I thenshowhow theprocessof eco-

This content downloaded by the authorized user from 192.168.72.230 on Mon, 19 Nov 2012 15:19:50 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

DEMOCRACY,

DEVELOPMENT,

AND THE PUBLIC

SECTOR

3

= In [ (I lk) +

nomicdevelopment changes theunderlying structure of preferences of votersand how these changes in turn modify, conditional on thepoliticalregime in place,the size ofthepublicsector. Consideran economycomposed of individuals endowed withdifferent levelsof assets (such as skillsand property). The income of each individuali is a positive functionof his assets and can be represented as Y, = inr where is the tax rate and k the level of public yi(T,k), vestment. On theone hand,theincomeoftheindividual is decreasing withthetax rate(ayil/ar < 0), sincedevoting time to leisure ratherthan work becomes more attractive as the tax rate increases.Moreover,higher incomes are more sensitive to tax ratesthan lowerincomes-in other theleisure-work efsubstitution words, withincomes(a2yl/ar < 0). On the fect becomessteeper otherhand,publicinvestment, thatis,policiesto payfor infrastructures, humancapitalformation, and regulatory theruleof law and secureproperty agenciesthatenforce rights, raisestheproductivity of factors, thusincreasing individual income(ayil/ak> 0). The intensity withwhich affects individuals' returns varieswith publicinvestment thelevelofincome.Forvery low levelsof income, public of labor investment increases themarginal productivity either or notat all-extensiveroad-building very slightly in subsistencefarming economies hardlychangesthe levelof development. Beyonda certainincome thresh> 0). Atvery are increasing old, k'sreturns high (aJ2y/lak to public investlevelsof income,the marginalreturn off(a2y/lak < 0). ment tapers The statetaxeseconomicagents a lineartax through r on their is then incomey.The resulting publicrevenue A is equally allocatedin two ways.A certain proportion distributed so that is given to amongall individuals, ATya each i,whereYais the averageincomeor Ya = Y

N

Ui

-y

(r

-y,

(-,k

Giventhatvotingtakesplace overthe tax rateand thatpreferences are related to pre-tax individual income (and hence single-peaked), thetax ratewill correspond to the ideal policyof the median voter. That is, policywill choose thetax ratethatmaximizes makers thewellbeing of the last voter needed to form a majority.4 Maximizing(2) withrespect to r,subjectto thebudget constraint, gives us the ideal tax rate of the median voter:

AYa (r,k)- Ym(r,k)TM

FJyJ

[a

T

I Ay

a

a

k

a

Jk Fy a

ka

T]

+ aY7m ,k LYm

a

Ymk1 (3)

Ym+

T

k

a

ak

i IN.

The rest, (1 - A)r, is spenton publicinvestment. The publicbudgetis always balanced,thatis,theexand transfers on investment penditure equals totalrevenue:

l=n

i=l

X Yi (T,k) = ATNYa (Tk) + (1-A)TXYi(T,k)

i=l

l=n

(1)

The utility of each agenti dependson three compoinitial the of the nents: income (affected by proportion tax directed to finance thenettranspublicinvestment); from ferreceived thegovernment (thatis,thelump sum from ofthetaxedinreceived thestateminustheportion come directedto financethe redistributive program); and, finally, the proportionof the income taxed to financepublicinvestment programs. Formally:

The followingassumptions,embedded in the model, makesurethatan interior theoverallinTmexists. First, come distribution is unequal (as a result ofdifferent asset and skewedto thetop,thatis,theincome endowments) of the median voteris lowerthan the averageincome the medianvoterwill always (Ya> Ym)'and, as a result, for vote (or will be promisedbypoliticians)a tax to redistribute thehigh-income incomefrom voters to himself.Second,voterswithhigherincomesare more sensitiveto taxes than voterswith lowertaxes (Oya/aT < thatTm > 0. Third, fora full ayml/T < 0), whichensures tax on income(T = 1), outputdropsto zero,and as a resultthe medianvoterwill alwaysvote forT < 1. Finally, it thetax rateis onlyincreased to thepointsthetransfers generatescompensate any decrease the tax raise may cause on themedianvoter's income. Fromthispolitical follow. twogeneral results set-up, thelevelofthetaxratewilldependon thedifference First, betweenthe averageincomeand the incomeof themedianvoter. The larger thedifference, thatis,themoreunincomedistribution, themoreinterested equal theoverall in redistribution the medianvoterwill become and the thetax ratewillbe. Still, thetax ratethatthemehigher dianvoter(or themedianparliamentarian) will approves offully incomesacrossvoters. Since stopshort equalizing to reducethe incentive highertaxes and redistribution which workand, withthat,lowerpre-taxincome,from themedianvoter willvotefora tax transfers arefinanced, rateto thepointin whichtheavailableamountof transfers declines.

40n the validityof median voter models, see Alesina and systems. For proporRosenthal (1995), chapter 2, forplurality participation of tionalrepresentation systems and thesystematic in coalition governments, see Laver themedianparliamentarian and Schofield (1990).

This content downloaded by the authorized user from 192.168.72.230 on Mon, 19 Nov 2012 15:19:50 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CARLES

BOIX

dian voterin a nondemocratic system is richer thanthe median voterin a fulldemocracy. Accordingly, at the same levelof development (forthesame distribution of income across individuals),the incentiveto investis higherin an authoritarian regimethanin a democracy. As incomes increase, however, and giventhatthe marginal return forpublic investment declinesat highper capita incomelevels, the differences acrossregimes(refrom locatedmedianvoters)in public sulting differently investment ratesshouldvanish. In thesecondplace,theleveloftranfers and thusthe size ofthepublicsector alters the changeas development distribution of assets across societyas folunderlying lows.Atlow levelsof development, thepublicsectorreA= -[(1- T)(ayi laA) + TYa in theeconomy. mainsmarginal This takesplace fortwo (rT k)] IT(aYa laA) (4) alternative reasons.On theone hand,in underdeveloped yet relatively thepressure to redistribute equal countries, TheDynamic PathofthePublic Sector: Economic Development andthePolitical Regime is limited-in line withthe predictionsof the Meltzer and Richards' model.In thistypeof premodern society, Withthe set of mechanismspredictedabove in mind, whichconstitutes the standardaccount of modernizaconsider now thetwo main channelsthrough whichthe own roughly similarplotsof land tion,peasantfamilies processof modernization, byaltering thedistribution of and are affected by similarrisks.Even thoughtheyare incomeacrossthepopulation, pushesthesize ofthegov- not universal, communalarrangements to shareriskernment upward. such as commonlands or church-distributed benefitsIn the first place,thepublic sectorexpandsdirectly and the use of extendedfamiliesforthe provisionof as a result of theprocessof economicdevelopment.5 As and caremaybe fairly extended. Thesefamfood,shelter, discussedin theprevioussubsection, inily- and community-based above a certain mechanisms risk-sharing an increase in theprovision forthestate. comethreshold, of collective substitute is Hence,evenifa fulldemocracy in place, the public sectorremainssmall. On the other has strongeffects on the goods and public investmerit productivity of factors. Accordingly, as theeconomyand and unequal societies, hand,in underdeveloped such as of policy- those characterized to grow, theincentive per capitaincomestart by a strong cleavagebetweenlandmakersto raise the supplyof capital and public goods ownersand a mass of landlesspeasants, althoughrediswillincrease. tributivepressuresare strong,they do not generally Most publicinvestment, to reap generated the benefitsof development, will take place indepentranslateinto a largerpublic sector.In such a society in place (or,moreprecisely, characterized ofthepolitical skewin thedistribution of dently regime bya substantial the uppersegment of theincomedistribution, oftheactuallocationofthemedianvoter on theincome incomes, the the distributional anticipating scale).6 Still,the typeof politicalregimemayaffect consequencesof democextentof public investment blockstheintroduction of democracy. Witha limpartiallyin the following racy, itedfranchise, the distancebetweenthe averageincome way.Assumingthatauthoritarian regimesexclude the from and themedianvoter's incomestays smallor evenneglithepolicy-making themepoorestvoters process, gible,and thepublicsectoris keptsmall.In short, at low levels of economic development,only low tax rates 5Fordiscussions of theprocessof economicmodernization, see shouldprevail, either becauseredistributive are pressures Floraand Alber(1981). For a critical examination, see Espinglow or because have been force. they suppressed by Andersen (1990). Fora first analysis of itsimpacton thepublic Economicdevelopment alters thestructure of social seeWilensky sector, (1975). the underlying sourcesof distributive relations, shifting 61t istrue, that cannot be automatically ashowever, policy-makers withthe following conflict, consequences.On the one sumedto behaveas socialplanners. The implementation of optimal policies willonlyhappenunderpolitical or legalinstitutions hand,overall itwas high)declines, inequality (whenever thateffectively restrain rent-seeking behavior amongpoliticians. lessening a fundamental sourceof politicalconflict, and

Democratic institutions, byeasingthetaskofmonitoring policymakers, may, on average, leadto a fuller provision ofpublicgoods. For a discussion of thispoint,see Olson (1993) and Przeworski inthisarticle, and Limongi (1993).In themodeldeveloped politiciansautomatically react to thedemandforproductive expenditure as determined bythelevelofincome.

Second,the tax ratewill be affected by the proportionspenton investment (1 - A) sincethisincreases the productivity of workers. The median voterwill choose theA suchthatthemarginal benefit she derives (through herincome) from thelastunitbeingspenton publicinvestment equals the netbenefit she derivesfromtransIn other fers. A willbe chosenat a value in which words, in themedianvoter's thecombinedincrease incomedue to publicinvestment and to theexpansion oftotaloutput (whichimpliesa larger pool availableforredistribution) in derived from thelastunitreceived equals theincrease transfers. to A,the Formally, maximizing (2) withrespect solutionis:

This content downloaded by the authorized user from 192.168.72.230 on Mon, 19 Nov 2012 15:19:50 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

DEMOCRACY,

DEVELOPMENT,

AND THE PUBLIC

SECTOR

the likelihoodof a democraticregimegoes up. Recent datacollected byDeininger and Squire(1996) on income inequality, consisting in 692 comparable observations (587 of themwithGini coefficients) show that,at low levelsofeconomicdevelopment, thedegreeofinequality is highly variableacrosscountries. For economiesunder a per capita income of $5,000,the mean Gini index is 42.5 withthevaluesranging from 20.9 to 66.9 and a standard deviation of 10.4.At higher levelsof economicdeof inequality In velopment, the occurrence diminishes. economies with a per capita income of more than $10,000(constant pricesof 1985),theaverage Giniindex is 34.2 with a standard deviation of 3.6. As recently shownin Przeworski and Limongi(1997), whereasthe probability of havinga democracy is lowerthan0.25 in countries witha per capita income of $2,000,it risesto over0.75 forpercapitaincomeshigher than$7,000.7 On theother and hand,technological breakthroughs the expansion of manufacturing and service-oriented the old economicstructure withthefoljobs transform In the first lowingconsequences. place,the distribution of economicriskchanges, in specific concentrating segmentsof thepopulation. More precisely, unemployment whichemergeas the spellsand work-related accidents, downsideof manufacturing-led productivity increases, become important among industrial workers, particuIn other thosemostunskilled. larly words, theprocessof industrialization and the formation of a broad class of wage-earnersresultsin strongerpressuresfor intragenerational transfers. in mateIn thesecondplace,a general improvement rial conditionsand in healthtechnologies in particular lifeexpectancy and eventually in prolongs leads to a shift thedemographic As theprofile of thepopulastructure. tionmatures of old cohorts and theproportion expands, in the formof pressureforinter-generational transfers, pensions and health care programs,goes up. Broadly speaking,whereasthe pressureforintra-generational transfers is a contemporary phenomenonto industrialization,the ageing of the population occurs at a later stagein modernsocieties. of extraordinary thisbackground social and Against economicchange, thelevelof transfers and hencethetax

re7Asis apparent, thisarticle treats thechoiceofthedemocratic democracy is degimeas exogenous. Fora formal modelinwhich rivedfromthe gains (or losses) thatpoliticalagentsconfront inturn, an outcome ofthepatunder different regimes (which are, theresources they haveto ternofincomedistribution) and from imposetheir preferred solution, see Boix (2000). In thatpaper, is also offered to showhowthepattern of inevidence empirical witheconomicdevelopment) comedistribution appears(jointly to explain thetype ofpolitical regime. as a fundamental variable

ratearestrongly shapedbythepolitical regime in place.In democratic regimes, where newly mobilized groups(such as unionizedworkers) can successfully pressfortheir demands,thesize of thepublicsectorincreases rapidly. By contrast, underauthoritarian regimesor restricted democracies, redistributive programs remain minimal. Finally, themodel allowsfora related prediction. As turnout declinesamongtheleastskilled voters, thepublic sectorshouldshrink evenifthefranchise is universal. In otherwords,in the limit,thatis, withall votersabstaining,the size of the public sectorin a democracy should be similarto the public sectorin an authoritarian system.

LawandBaumol's CostDisease Wagner's

The theoretical explanation developedin the article difbothWagner's Law and Baumol'sCost Disease, fers from whichhave constituted thetwo mostcommonexplanations employedto linkeconomic modernization to the size ofthepublicsector. law states thatpublicexStrictly speaking, Wagner's penditure riseswithsocial progress because thetypesof goods and services providedby thepublic sectorhave a high income elasticityof demand. This explanation, whichtreats percapitaincomeas a blackbox (a problem thisarticle to overcome) and disregards howvotattempts has ersreactto thetax burdenof morepublicspending, foundvery scantsupportin previousempirical analyses (Ram 1987). 8 In turn, theso-calledBaumol'scostdiseasepredicts in of similar realwagesincrements thatthecombination boththepublicand theprivate sectors and a lowerproratein thepublicsector(whichis a serductivity growth indusvice sectorand hence a relatively labor-intensive sectorleads to an try)comparedto the manufacturing in realterms increase ofthecostsof government services Baumol onlyclaims overtime(Baumol 1967).Although that(publicemployment costsshould and) publicsector on the grow over time in absolute terms,researchers growthof the public sectorhave oftenconcluded that size of the thisshould entailas well a risein therelative in the economy.9As formally shown in government

8Abroaderversionof Wagner's Law is basicallysimilarto any of the thegrowth explanation and relates theory modernization into society to thetransformation ofthetraditional publicsector of understanding Thismuchbroader economy. an industrialized in themodeldeaccommodation somepartial Wagner's Lawfinds (1988). see Lybeck Fora discussion, veloped here. see Holseyand 9Fortheuse ofBaumol'smodelin thisdirection, cited therein. (1998:568-569)and thereferences Bordering

This content downloaded by the authorized user from 192.168.72.230 on Mon, 19 Nov 2012 15:19:50 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CARLES

BOIX

1. "Economy" includesthesetofvariables thatmeasuretheeffects ofeconomicmodernization on thesize of government: (a) The log value of realper capitaincome(in conin internaChain Index,expressed stantdollars, tional prices,base 1985, taken fromthe Penn in the WorldTables),thatproxiesforthe shifts of preferences distribution associatedwitheconomic development, is expected to have a posiDataandMethods tiveeffect on thesize ofthepublicsector. (b) The average shareof theagricultural sectorover Sample GDP in 1970-90, takenfromtheWorldBank, To examinethe strength of thetheories in the and expected to enter in themodel. reviewed negatively I build a samplethatincludesall thecounfirst section, (c) The "old-agedependency thatis thenumratio," ber of yearslifeexpectancy goes beyond60, in triesforwhichcomparable data on publicrevenue(currentreceipts)of the generalgovernment are available 1970-90;lifeexpectancy is takenfrom theWorld from1950to 1990.Two sourceshavebeen used to build Bank.Thisvariable, whichtracks theshift ofthe medianvoter to an olderage,shouldaffect posithissample:theUnitedNationsNationalAccounts(UN, severalyears) and the OECD National Accounts.The thesize of government.10 tively of redata startsin 1950 and approximately coverssixty-five (d) The Gini index,to measurethe existence countries are OECD members), withsome distributive takenfrom and (twenty-two tensions, Deininger variationin the yearscovered,providingabout 2,000 Squire(1996). 2. "Trade," data points. See Appendix B for a descriptionof the whichmayincreasethe risksassociated withtheinternational businesscycleand hencepolitical sample. forpublicly-financed pressures compensatory programs in favor which of the exposedsectors. This variable, has Dependent Variable of publicsector(see been foundto be a strong predictor of thegeneral Cameron1978;Rodrik1996),is measured The dependent variableis current receipts through: Current havebeen chosenoverpub(a) the log value of the ratioof trade (sum of imgovernment. receipts lic expenditure to maximizethe sample underanalysis. to GDP,and is takenfrom the portsand exports) PennWorldTables; The UnitedNations National Accountsoffer less comdata on public disbursements. for two prehensive Although (b) the ratio of fuelexportsovertotalexports, WorldBanktables; 1970-90,takenfrom databasesoffer larger samplesforpartsof publicexpenof nonfuel (c) and theproportion primary exports diture, theyare not well suitedforthe purposesof this article. The PennWorldTablesreportthe shareof govover total exports,for 1970-90, taken from WorldBanktables. ernment ofovera hundred countries-but consumption includes: a fractionof all 3. "Political Institutions" government consumptionrepresents whichindi(a) The variable"DemocraticRegime," government spending.The World Bank's WorldData each country 1995 reports levelsof overallgovernment cates whether was a competitive spendingfor in thefive Data overeighty countries. theWorldBank'sWorld Still, democracy previous years-and thus ranges from0 (no democracyever) to 1 (de(as well as the IMF data) reportsspendingonly at the centralgovernment level-which leads to rather biased mocracyalways).To measurethe presenceof a I follow valuesforcountries suchas Argentina, theindexdeveloped democratic India,or theUSA. regime, et al. (1996) and theclassification rebyAlvarez in Appendix A of theirpaper. Demoported ModelandIndependent Variables "in craticregimesare definedas those regimes In orderto determine whichvariablesinfluence size of 10 I estimate thefollowing model: government, as follows. ratio" The"old-age dependency (ODR) is calculated = cx PublicRevenues + cx1(Economy) + cX2(Trade) + xo3(Political Institutions) + cx4(Economy Political Institutions) + ? This variable over the ofthe over isused 60 proportion population tomaximize the number ofobservations. ODR andthe percentage ofoldpopulation arehighly correlated (with the correlation coefficient of0.82).

ODR = Lifeexpectancy (LE) - 60 ifLE > 60,ODR = 0 otherwise.

Appendix A, thisextension of Baumol'sworkis inaccurate.The higherproductivity of manufacturing private sector maylead to a higher wagebillin thepublicsector. in productivity But the differential (whichexpandsthe tax base to finance the state)prevents the public sector from automatically taking a bigger shareoftheeconomy.

This content downloaded by the authorized user from 192.168.72.230 on Mon, 19 Nov 2012 15:19:50 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

DEMOCRACY,

DEVELOPMENT,

AND THE PUBLIC

SECTOR

7 tion is thatthe interactive termwill have a positiveimpacton thesize of government. FollowingBeck and Katz's procedure,I have estimated the pooled cross-sectionaltime- series model leastsquares, erthrough ordinary adjusting thestandard rorsforunequal variation withinpanels and correcting forautocorrelation.12

whichsome governmental offices are filled as a elections" consequenceof contested (Alvarezet al. 1996,4).11 in Democracies," (b) "Levelof Turnout whichis an interactive termof "Turnout" and "Democratic The variable is defined as the Regime." "turnout" proportion ofthosevoting overall thosecitizens IDEA overthelegalvoting age and is takenfrom (1997) and has been calculated foreach yearon thebasis of data from thathave taken elections place in theprevious five years. Bothdemocracy and thelevelofturnout are expected to increase thesize ofthestate. variables (c) The following three to capturetheextentto whichdifferent constitutional arrangementsdistort of the median the representation voter's preferences: variableforthe (i) a dummy presenceof presidential regimes;(ii) a dummy variablecodingtheuse or not of a proportional representationelectoral system; and (iii) a dummy variablethatcaptures theexistence of a federal system. The first twovariables havebeen builtbased on Cox (1997), IDEA (1997), Linz and Valenzuela (1994), Shugart and Carey (1992) and theKeesing's Contemporary Archives. The variable on federalismfollows Downes (2000). 4. Although theprocessof modernization generates, on itsown,strong to increase thepublicsector, pressures thethrust of themodel predicts thatthe size of governmentwillgo up conditional, to a largeextent, on thepoliticalregime in place.Excluding theprovision of public goods,thepublicsectorwillremainsmallin authoritarian regimes.In democraticregimes,instead,governments willmeetthedemandsfor transfers fostered bythe economicand demographic and thesize of the changes, I public sectorwill increase.To capturethisprediction theinteractive term introduce Insti"Economy*Political in whicheconomicdevelopment tutions" is alternatively measuredthrough per capita income,shareof agriculture, old-age dependencyratio, and Gini index, and wherepoliticalinstitutions are both democratic regime and levelof turnout in democratic The expectaregime.

1II havealsoregressed thedependent variable on a variable that indicateswhether each country was a "bureaucracy" each year;a variable thatindicates whether each country was an "autocracy" eachyear; and a variable whether eachcountry thatindicates was independent eachyear. Bureaucracies arethosedictatorships that havelegislatures. Autocracies arethosedictatorships thatdo not and that therefore can be thought ofas nothaving anysortofinrulefor stitutionalized operating thegovernment. Thepresence of andbureaucracies is alsobasedon theindex autocracies developed etal. ( 1996). byAlvarez

SamplePeriods

The analysishas been conductedon two data periods, of data: (1) The first due to the availability data set includes observations fortheperiod 1950-90 and the following independentvariables:real per capita income, and imports overGDP, and political varisum ofexports in Table 1. (2) A second data ables. Resultsare reported to theperiod 1970-90,adds theremaining set,restricted independent variables listedin theprevious section(and in 1970). Resultsare reported forwhichdata onlystarts in Tables2 and 3.

EMPIRICAL RESULTS

TheImpact ofDevelopment and Democratic Institutions

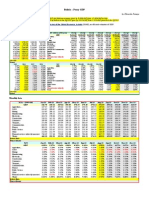

Table 1 examines theimpactof themainvariables ofthe or modernization, model,economicdevelopment political regime,turnout,and theirinteraction, on current fortheperiod 1950-90. It also includes public revenues a controlfortradeopennessand testsforthe impactof on the size of the different constitutional arrangements state. Both economic developmentand trade openness, whichare strongly froma statistical significant pointof the size of government. As disview,affect positively cussed above,theimpactof socioeconomicmodernization is to a largeextentconditionalon the politicalreColumn 1 introduces the gimeand levelofparticipation. interactive term"DemocraticInstitutions*(Log of) Real perCapita Income."'13

12Estimations in Tables 1 through3 have been implemented has beenmodthrough Stata's xtpcse procedure. Autocorrelation a common eledas a first-order process with coefficient for allpanels.Results do notchange with panel-specific autoregressive terms. Moreover, thefollowing tests havebeen developed to ensure the robustness of results: country-by-country and year-by-year deletionsas wellas introduction ofdummies areas. Results byregional wererobust to this procedure except where noted.

13 United NationsNational Accounts do notincludedataon thesize of thepublicsectorin former socialist countries. Using IMF (several I haverunthesameregressions in data from years),

This content downloaded by the authorized user from 192.168.72.230 on Mon, 19 Nov 2012 15:19:50 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

8 TABLE I

CARLES

BOIX

The Size ofGovernments across theWorld

PublicRevenueas Percent ofGDP,1950-1990

Independent Variables Constant PerCapita Income (Log)a TradeOpenness (log ofsumof and imports overGDP)b exports Democratic Regimec Democratic Regime* Log ofReal PerCapita Income inDemocratic LevelofTurnout Regimes LevelofTurnout* Log ofReal PerCapita Income Proportional Representation inDemocracies Presidential RegimeinDemocracies inDemocracies Federalism ModelChi-square Prob>Chi-square R2 ofobservations Number

(1) -27.71*** (7.87) 4.62*** (1.05) 3.77*** (0.57)

-14.81A

(2) -28.01* (8.79) 5.10*** (1.14) 2.52*** (0.62) 2.36 A (1.99)

(8.87) 2.16*** (1.15)

-0.30** (0.14) 0.04** (0.02) 1.72 (1.08) -3.87*** (1.17) -0.55 (1.22) 533.99 0.0000 0.667 1975 1.77* (0.98) -3.84 (1.12) 0.05 (1.28) 540.90 0.0000 0.778 1384

aPerCapita Income, PennTables. Log ofpercapita GDP in$ in 1985 constant prices.Source:World bTrade and imports overGDP. Source:World PennTables. Openness. Log ofthesumofexports inprevious 5 years)to 0 (non-democracy inthe cDemocratic institutions. Variable Regime.Five-year average ofdemocratic goes froml (democracy five data inAlvarez, and Przeworski previous years).Averagecalculatedfrom Cheibub,Limongi (1996). lastsquares estimation and correction for Estimation: standard autocorrelation and for heteroskedastic disturOrdinary , with panel corrected errors, bances betweenpanels. inparenthesis. errors Standard < 0.01 *p < 0.10; **p< 0.05; ***p Aln joint testwith levelofturnout indemocracies, statistically significant (Prob> chi2 = 0.0000).

as a proFigure1 theevolution ofcurrent publicrevenue portion ofGDP as realpercapitaincomerisesunderboth a democratic polityand an authoritarian regime(trade Table 1 including totalrevenues of general government in Hunhasbeensetequal to thesamplemeanof62 peropenness gary (1981-89),Poland(1984-88),Yugoslavia (1971-89),and Roofthesimulation in Figure1 mania(1972-89).No dataareavailable forChina,EastGermany, centofGDP). The structure In the facts. the first place,the suggests following stylized TheseretheUSSR,and other non-European socialist countries. gressions, withand withouta dummy variablefor"planning levelofdevelopment impact has,again,an unconditional estimates similar to theresults obtained generate very economies," sector. At low of developon the size of the public levels forplanning econowithout anyplanning systems. The dummy thepublicsector is small.Democratic India,theaument, miesindicates that thesizeofthepublic sector is about20-25percentage points ofGDP larger in socialist economies. Froma theothoritarian regimesof sub-Saharan Africaor Central reticalpoint of view,we maywantto concludethatsince the Americaor eventhelimited democracies of nineteenthofincome(yi)to tax (r) is muchlower in countries that elasticity fit this into The state thengrows century Europe pattern. have socializedthe means of production, the statetaxesmore heavily there. withpercapitaincome.Regardless ofthepolitical regime To interpret theresults ofColumn 1,Table1,and particularly the effect of the interactive term, I simulatein

This content downloaded by the authorized user from 192.168.72.230 on Mon, 19 Nov 2012 15:19:50 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

DEMOCRACY,

DEVELOPMENT,

AND THE PUBLIC

SECTOR

FIGURE1

45

n 0

0 35

of PublicRevenueas an Interaction The Evolution of and Political Regime EconomicDevelopment

40

@ 30 30 ,

..

Q) 25

n 20

L

15

10

2,000

4,000

6,000

8,000 10,000 12,000 14,000 16,000 18,000

(1985 US $) PerCapitaIncome

The Public Sector Under a Democratic Regime

- ---

Regime The Public Sector Underan Authoritarian

in place,thesizeofpublicrevenues increases byaround10 low to mediumlevelsof depercentage pointsfrom very velopment, and thenanother5 percentage pointsfrom mediumto highlevelsof development. In the second place, the natureof the politicalregimedoes not affect, on its own,thesize of thegovernment.Forthatto be true, thepublicsector shouldalways be larger undera democratic system at all incomelevels. The resultsshow,instead,that democraticregimesin economieshave no incentives truly underdeveloped to spendmorethanauthoritarian Atextremely low regimes. levelsof development, public current revenue is,in fact, somewhathigherin nondemocraticregimes.At a per capitaincomeof $250 (in 1985prices), is publicrevenue almost3 percent lowerin democracies thanin authoriThis is due to two factors. tarianregimes. First, the demands fortransfers associatedwithdevelopment have not affected democratic states. authoritarian reSecond, gimes, withtheir comparatively richer medianvoters(in relation to democracies), haveslightly moreincentives to It is also likely spendon capitalformation. thatauthoritarianstatesare more expensive due to theirneed to financetheir repressive apparatus. as socioeconomicmodernization takesoff, Finally, lead to larger democratic institutions The governments.

latter generates a set of demandsand needs thatdemocratic politicians needto respond to. Once realpercapita incomegoes over$1,000,thepublic sectorexpandsat a faster rateunderdemocratic regimes. Witha per capita incomeof $ 6,000,publicrevenueis about 4 percentage For a per capita pointshigherin a democratic country. incomeof $12,000,publicrevenue would hypothetically be 6 percentage pointshigherin a democracy. The hisfits toricalexperienceof recentdemocratictransitions case theseresults Considertheparadigmatic quitenicely. in thelate was reestablished of Spain,wheredemocracy 1970s.In 1974,Spain had a per capitaincomeof $7,291 (in 1985prices)and itscurrent publicrevenue amounted to 22.8 percentof GDP. Ten yearslater,althoughper capita incomehad remainedstagnant(it was $7,330 in 1984),current publicrevenue had risento 32.7 percent.14 Accordingto the model in section 1, who actually votesshouldmatter as much(or evenmore) thanwho is I use, a demo'4Inthe sample other countries that went through cratic a similar ofbehavior. This is case transition exhibit pattern

ofGreece andPortugal OECD nations. non-OECD among Among in Philippines, forexample, current went nations, publicrevenue 14percent ofGDP after ofGDP to 19percent therestoraup from tion of democracy in thelate 1980swithout per capitaincome in that changing period.

This content downloaded by the authorized user from 192.168.72.230 on Mon, 19 Nov 2012 15:19:50 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

10

CARLES

BOIX

FIGURE

The Evolution of PublicRevenueas an Interaction of EconomicDevelopment and Democratic Participation

45

n 40

35

30

15 10

2,000

4,000

6,000

8,000

10,000 12,000 14,000 16,000 18,000

Per Capita Income (1985 US $) The Public Sector With FullElectoralParticipation ---- The Public Sector Underan Authoritarian Regime The Public Sector WhereTurnout Equals 50 Per Cent ofthe Electorate

legallyentitled to vote.Changes in the level of turnout mayshift thepositionofthemedianvoterand henceaffectthe tax rate.Since individualdata on participation are unavailableforall the countriesin the sample,this hypothesis can onlybe tested usingnational levelsofparticipation. Nonetheless, giventhat, holdingotherthings constant, the individualprobability of votinghas been shownto increase withincome, itis plausible to conclude thatas nationalturnout declines, abstention mostly takes place amongthepoorestvoters.15 Hence,at lowerlevels inofparticipation, thedifference between medianvoter come and average incomeshoulddeclineand thesize of thepublicsector shouldshrink. Column2 in Table 1 considers theeffect oftheinteractive term and percapitaincome.16 ofturnout The coefand strongly ficientis again significant confirms the in Table 1, Coltheoretical model.Usingthecoefficients umn 2, Figure2 simulates the impactof different levels of turnoutunderdifferent conditionsof development.

on theabsence 15Forevidence that, ofmechanisms ofpolitical moorunions, is positively to bilization, suchas parties turnout related income, seeRosenstone and Hansen(1993) and Franklin (1996).

16 The introduction ofthevariable "LevelofTurnout" shrinks the sample byalmost 600 observations.

Again, in underdeveloped countries, participation has no impact.For mid-incomenations,however, turnout becomes substantially important.For high levels of per capita income,the size of thepublic sectorvariesfrom 37.5 percent ofGDP in countries whereonlytwofifths of the population vote (the cases of the USA or Switzerland) to about43 percent whereeverybody votes.17 As noted above, Table 1 also tests the impact of presidentialism, proportional representation, and federalism.Federalism has no impacton thesize ofthepublic sector. Froma theoretical standpoint, theimpactof proon thesize of thepublicsector portionalrepresentation is unclear.On the one hand, it has been pointed that while in plurality systems politicianscan targeta few marginaldistricts withverynarrowly designed redistributive needto pleasea largenumber programs, parties of voters(acrosstheentire underproportional country) representation (Perssonand Tabellini1998). Yet,on the other dishand,provided thatthepopulationis similarly tributedacross the country, all parties should be expected to (partly)converge to the median voterunder thetwo systems and thusimplement similar policypro17For recent evidenceon the impactof turnout on the size of transfers using thesampleofOECD nations, see Franzese (1998).

This content downloaded by the authorized user from 192.168.72.230 on Mon, 19 Nov 2012 15:19:50 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

DEMOCRACY,

DEVELOPMENT,

AND THE PUBLIC

SECTOR

11

grams.18 Table 1 showsthatthe public sectoris slightly underproportional largerin countries governed representation of GDP-but it is laws-by about 1.7 percent not significant in Column 1 (whichemploysthelargest sample).'9 By contrast, has a significant presidentialism negativeeffect on the size of the public sector.Under presidential systems, public revenues are around 4 percentof GDP lowerthanunderparliamentarian regimes. Although presidentialism significantly depresses participation (by over 12 percentage pointsin myestimations does not wane on the sample of this article),its effect once we controlforturnout. The separation-of-powers thatcomes withpresidentialism seemsto imstructure bias on current pose a status-quo policythatslowsdown of government.20 thegrowth

TheMechanisms ofDevelopment

As discussedin thetheoretical part,economicdevelopment or, more generally, a modernizationconstitutes thedistribution of risk thatalters complexphenomenon and generations. In thepreviand incomeacrosssectors ous subsection, thelevelofdevelopment, measured using per capita income,was employedto some extentas a to estimate how economicmodernization proxy affected, both the throughthe mechanismsspelled out earlier,

is truethatwhereas the 181t underproportional representation, closeto themedianvoter, medianparliamentarian willbe always in government under one shouldexpect morevariability plurality thatis, on average, But overtime, composition. policylocation similar should be thesamegiven electorates. ofproportional representation oscillates in size 19The coefficient or countries. whenwe exclude specific years Proportional repreto affect thesizeofgovernment in an indisentation seems mostly rect way:byreducing barriers to entry and diminishing theincentive to vote strategically, it boosts political participation-a well-known result in theliterature on electoral turnout (Franklin 1996)-and therefore makes government moreresponsive to citizens'demands. Controlling foreconomic development, degree of party competition,and other institutionalcharacteristics (presidentialism and federalism), turnout is around9 percentage in proportional in thedata pointshigher representation systems is excluded setusedin thisarticle. Whenturnout from Column2 in Table 1,proportional representation becomesstatistically sigand goesup to 2.4. nificant 20For a different of theimpactof presidentialism, interpretation and Tabellini see Persson (1998). Usinga muchsmaller sample(a cross-section ofaboutfifty Persson and Tabellini esticountries), mate that presidential systems depress public expenditure byabout of GDP. Theyattribute 10 percent itsnegative effect to thefact ofpotential conflict theextent that, bysharpening amongpolitiof powerssystem enablesvoters to discipline cians,a separation and therefore to reduce thelevelof rents. Theirtheopoliticians Thesizeofrents retical explanation is,however, unconvincing. apthebudget propriated bypoliticians through cannotaccountfor this differential between andparliamentarian presidential regimes.

provisionof public goods and the demands forredistributive programs. one, I atIn both thissubsectionand the following usingmore temptto unpackthe effects of development directmeasuresthatcapturethe changein the underlyof preferences due to the growthof a ing distribution manufacturing working class (leading to larger and theagingofthepopulaintragenerational transfers) tion (resultingin an expansion of intergenerational Moregenerally, I also consider theeffect ofthe transfers). levelof incomeinequality. for overall Since observations thosemeasuresare morescarcethanper capita income to betweena halfand a third data,thedata setdwindles oftheinitial theresults arein linewith sample.Although themodel of thearticle, it is important to have in mind thesedata constraints whenexamining theestimations. Table2 examines theimpactofbothindustrialization and demographic changeson thesize ofthegovernment fortheperiod 1970-90. In Column 1 I add two factors, the shareof theprimary sectorin the economyand the and itsinteraction withdemoold-agedependency ratio, in Table 1craticregime to theinitialmodel estimated I excludeherethevariablesof proportional representaand federalism to maximizean altion,presidentialism, smaller size ofthe ready sample.Sincepercapitaincome, correprimary sectorand lifeexpectancy are strongly sector lated-for anygivenyear, thesize of theprimary of and old-agedependency explainaroundof 80 percent thevariancein thelog of per capitaincome-I drop the levelofpercapitaincomein Column2. In bothcolumns thetwonewvariables as expected. perform Consider the resultsin Column 2 in Table 2. The of theprimary sectorin the economyhas a subweight of thesize of thepublic stantial impacton theevolution A decreaseof one percentage sector. pointoftheagriculin theGDP impliesan increase ofpublicrevturalsector enue of 0.30 pointsof GDP. Withall the othervariables at theirmean level,public revenueswould amount to in a country withno agricultural secaround36 percent torand to about 18 percent in a country withtwo-thirds in theprimary oftheeconomy sector. Modernization, by of most of the the types productive activities changing an urbanworkpopulationis engagedin and bolstering of a siging class,accountsformuch of the emergence as predicted in the Noticealso that, nificant publicsector. faster translates model,the processof industrialization undera democracy: thepublic intoa bigger government sectorgrowsby another0.17 pointsforeach percentage dropin thesize of agriculture. The proportionof old population has, in turn,a on the size of government-constrongpositiveeffect firming the standardliterature on the determinants of

This content downloaded by the authorized user from 192.168.72.230 on Mon, 19 Nov 2012 15:19:50 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

12

CARLES

BOIX

TABLE

The Size ofGovernments across theWorld: The Mechanisms ofModernization

PublicRevenueas Percent ofGDP,1970-1990

Independent Variables Constant Per Capita Income (Log) Share ofAgricultural SectorinGDPa Old-AgeDependency Ratiob TradeOpenness c Democratic Regime Democratic Regime* Share ofAgricultural Sector Democratic Regime* Old-AgeDependencyRatio LevelofTurnout inDemocratic Regimes LevelofTurnout* Share ofAgricultural Sector LevelofTurnout* DependencyRatio inDemocracies Proportional Representation Presidential RegimeinDemocracies inDemocracies Federalism ModelChi-square Prob>Chi-square R2 No. ofobservations

(1) -22.05** (10.12) 4.12*** (1.22) -0.20*** (0.07) -0.05 (0.21) 4.92*** (0.73) 2.46 (2.93) -0.14A (0.11) 0.17A (0.21)

(2) 11.46*** (3.47)

(3) 17.51*** (4.57)

-0.30*** (0.07) 0.17A (0.19) 4.76*** (0.75) 4.37A (2.76) -0. 19** (0.10) 0.17A (0.21)

-0.33** (0.14) 0.30A (0.25) 2.76*** (0.81) -7.42 (8.55) 0.57* (0.32) 0.22A (0.58) 0.13 (0.10) -0.01*** (0.00) -0.001A (0.007) 5.53*** (1.12) -4.45*** (1.39) 1.67 (1.44)

374.28 0.0000 0.798 972

330.19 0.0000 0.790 972

418.10 0.0000 0.855 697

BankTables. ofGDP from sector.Source:World aShareofAgricultural Sector.Percentage agricultural BankTables. Ratio.LifeExpectancy. Source:World bDependency and imports overGDP. Source:World PennTables. cTradeOpenness. Log ofthesumofexports disturwith standard and correction for autocorrelation and for heteroskedastic Estimation: lastsquares estimation, Ordinary panel corrected errors, bances betweenpanels. inparenthesis. errors Standard * p < 0.10; **p< 0.05; ***p < 0.01 = 0.0000). and theinteractive AIn testofshareofagricultural sectorordependency, democratic institutions joint term, statistically significant (Prob>chi2

thewelfare statein OECD nations.For each yearlifeexpectancy increases beyond60, thepublicsectorgoes up 0.17 percentage pointsof GDP (Column 2)-only 0.05

points if we maintainper capita income (Column 1). imsubstantial The agingof themedianvoterhas a very pact conditional on the political regime in place. In

This content downloaded by the authorized user from 192.168.72.230 on Mon, 19 Nov 2012 15:19:50 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

DEMOCRACY,

DEVELOPMENT,

AND THE PUBLIC

SECTOR

13

democratic regimes, eachyearof lifeexpectancy beyond 60 adds another 0.17 percentagepoints to the public

sector.21

mation of Table 3 is based) from 312 to 617 data

points.24

Finally, Column 3 in Table 2 adds the variablesof turnout, alone and in interaction withagriculture and old-agedependency ratio,as well as the controls forinstitutional arrangements. This specification corresponds in Column 2, Table 1. Agriculto the model presented turedepressesand an old populationincreasesthe size of the public sector. the effect of industriInterestingly, alization on the public sectorbecomes more intense In throughturnoutratherthan democraticregime.22 turn,an aging population continues to have a much levelsof stronger impactin democratic regimes-higher turnoutin combinationwitha higherold-age dependencyratios actuallyreduce public revenue,although theimpactis negligible.23

Income andthePublic Sector Inequality

Table 3 examines thedirect impactthatincomeinequalityhas on the size of the public sector.To measureinI employthe data set collectedby Deininger equality, I have done two and Squire (1996). For the estimation, I have employedan adjusted Gini coeffithings.First, 0 to 100) to control for cient(thatvariesin a scale from in themethodsused to measure cross-national variation of the This variationis a function incomedistribution. unit (individualor household), choice of the recipient the use of grossversusnet income,and the use of expenditure or income. Following the suggestions of Deiningerand Squire,the adjustedGini is equal to the based on Gini coefficient plus 6.6 pointsin observations expenditure (versusincome) and 3 points in observathangrossincome.Second,I have tionsusingnetrather calculateda five-year movingaverageof adjusted Gini it miniThis procedure has twoadvantages: coefficients. in the inequalitymeasures;and it mizes the volatility doublesthenumberof observations (on whichtheestioffuel over total toconthe 21Adding proportion exports exports trol for the ofsubstantial oilrevenues doesnotchange the impact inTable a larger 2.Asexpected, oilexporters have coefficients govissmall. the effect ernment-although

22

In Column 1,per capitaincomeand tradeopenness stillplay a significant role in the growthof the public sector. Similarly, thepresence of democratic institutions continues to affect The Gini inthesize of government. dex is positiveand statistically significant. As income distribution widens,political demands forredistributiongo up. For each pointtheGiniindexincreases, public revenues rise0.4 percent of GDP-this translates into a difference of 19 percentage pointsof GDP between the minimumand the maximumvalues of the sample.The interactive termof the Gini index and democracyis and thus contrary slightly negative, to the model, but statistically not significant. The levelof politicalparticipation boosts public revenuein line withpreviousresults.The interactive termofturnout and theGiniindex has a negative impacton thepublicsectorand is statistiThe size of thiscoefficient callysignificant. impliesthat only at veryhigh levels of income inequality (over a Giniindexof 62) do higher translevelsof participation lateintoa slight dropin government size-for themaximum value of the Gini indexin the sample (66), it falls low to highlevbylessthan 1 pointwhenone goes from els of turnout.The waningeffects of higherparticipation on government size at veryhighlevels of income to the following fact.For inequalitycan be attributed thatis, in societieswitha veryhighlevelsof inequality, of the rich, of incomein favor veryskeweddistribution anyreasonablelevel of turnoutwill lead to have a median voter witha low income.Therefore, in anyincrease will not change significantly the already participation between insubstantial distance themedianand average formuch more equally distributed come. By contrast, income structures, participationwill correspondingly increasethe distancebetweenthe medianvoterincome and average income and will thereforeaffectmore thesize ofthetaxburden. strongly Column 2 in Table 3 includescontrolsforshareof and old-age dependency agriculture ratio,alone and in interactionwith democratic regime.25 Although the themodel behavesin sampledropsto 425 observations,

Table3 cannot 241t is important tostress that theconclusions from

Buta simulation oftheresults Sector" is herepositive. shows that, and theinthenegative coefficient of"Democratic given Regime" of"Turnout*Share ofAgricultural authoriteractive term Sector," tarian havelower levelsofpublicrevenue thandemocraregimes ciesfor similar levels ofindustrialization. turnsout to increase 23Notice thatproportional representation public revenues verysubstantially. Still,the size of the sample oftheone in Table1) weakens thisresult. (abouta third

inTables1 term "Democratic ofAgricultural be automatically totheuniverse Theinteractive Regime*Share extrapolated employed

to bring forth thisfact. and 2. Twotraits ofthesample areenough In thedatasetof 1975observations inTables1 and 2,65 employed have and 52 percent ofthecasesareauthoritarian percent regimes in Table Giniindexes below40. In thedatasetof617 observations aredemocratic haveGiniindexes beand 59 percent 3, 85 percent low40. withlevelofturnout 25Their interactive terms havenotincluded given thepossibility ofmulticollinearity effects.

This content downloaded by the authorized user from 192.168.72.230 on Mon, 19 Nov 2012 15:19:50 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

14

CARLES

BOIX

TABLE

The Size ofGovernments Testing theImpact ofIncomeDistribution across theWorld.

ofGDP PublicRevenueas Percent

Independent Variables Constant PerCapita Income (Log) Share ofAgricultural Sector Old-AgeDependencyRatio TradeOpenness

(1) -73.20*** (11.80) 7.85*** (0.64)

(2) 0.82 (11.08)

Q0.57*** (0.18)

0.21AA

(0.23) 3.91*** (0.68) 9.18A (14.00) 0Q40** (0.22) -0.21 (0.30) 0.31*** (0.12) -0.006** (0.003) 3.20*** (0.83)

17.99A

Democratic Regime

GiniIndex Democratic Regime* GiniIndex LevelofTurnout inDemocracies LevelofTurnout* GiniIndex Sector* ShareofAgricultural Democratic Regime Old-AgeDependencyRatio* Democratic Regime ModelChi-square Prob>Chi-square

R2

(15.84) 0Q44** (0.20) -0.48 (0.32) 0.28* (0.15) -0.005* (0.003)

0.10AA

(0.19)

0.08AA

(0.25) 585.73 0.0000 0.916 617 405.87 0.0000 0.923 425

No. ofobservations

disturandcorrection for autocorrelation andfor heteroskedastic lastsquares with corrected standard Estimation: errors, estimation, panel Ordinary bancesbetween panels. inparenthesis. Standard errors * p < 0.10;**p < 0.05;***p < 0.01 = 0.0000). AIn test ofshare ofdemocratic Gini index andtheinteractive term, statistically significant (Prob>chi2 institutions, joint = institutions test ofshare ofagricultural sector ordependency, democratic andtheinteractive statistically significant (Prob>chi2 AAln term, joint

0.0000).

The shift linewithprevious results. to bothan industrialized economyand a morematurepopulationas well as higherlevels of inequalitytranslateinto a largerstate. rateslead Similarly, democracy and strong participation to a biggerpublic budget. The impact of the demointenseunder graphictransition becomes particularly The creation of an industrial workdemocratic regimes. instead,do ing class and the level of overallinequality, to boost not seem to interact withpoliticalinstitutions

results are Partoftheselatter thesize ofthepublicsector. in of the observations not strange giventhat85 percent Column 2, Table 3 are democraticregimes.Giventhis "GiniIndex"is sample, thevariable highly homogeneous withinpressures associated picking all theredistributive

equality.26

26The decline with turnout, sector doesinteract oftheagricultural

as shown in Table2. however, toboostthepublicsector,

This content downloaded by the authorized user from 192.168.72.230 on Mon, 19 Nov 2012 15:19:50 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

DEMOCRACY,

DEVELOPMENT,

AND THE PUBLIC

SECTOR

15

arrangements and electoral systems havelittle impacton thestate.In short, the structure of societalinterests and electoral preferences always emerge as the key factor to The exploration of the forces thathave shaped the ecostudy to understand the role of the public sector across nomicroleof thestateacrossdevelopedand developing nationsshowsthatmodernization playsa fundamental, nations. yetnot mechanical,role in determining the size of the Manuscript submitted September 16, 1999. publicsector. Final manuscript received June 16, 2000. The process of economic modernizationleads to largerpublic sectorsin two different ways.On the one hand,theopportunities granted bya potentially growing economyspurpublicintervention. To cope withmarket failures thathauntthe provisionof keyinfrastructures A. APPENDIX and to setup a regulatory framework thatboostsprivate Baumol's CostDisease andthe states investment, taxcollection. maystepin and increase Growth of thePublic Sector On the otherhand,economicdevelopment leads to the of redistributive demands due to structural generation Following Baumol'scostdiseasemodel,ithas beenargued changes.In the first place, whereasrisksare generally that that thepublicsector in activities given is engaged that commonto mostindividuals in agrarian modsocieties, experiencelower productivity growththan nonpublic erntechnological shocks lead to thedifferentiation ofthe and giventhatthedemandfor (manufacturing) sectors, populationaccording to skillsand risks, such as induspublic services is (politically) fixed, over time thepublic secand joblessness, in particular trialaccidents of segments and will, torwilluse morelaborinputs implicitly, consume the population.Withthe decline of extendedfamilies, a growing partof theeconomy's resources. Although the thetraditional meansofsupporting in economic workers first conclusion maybe true(and publicemployment may downturns, thatis, informal help fromrelatives, disapgrow), thesecondresult doesnotfollow, however, from the pear.Collectiveinsuranceschemesmustthenbe develmodel. In thesecond oped to ease theimpactofunemployment. Baumol(1967) to theanalysis ofthe Set-up. Applying in the areas of food place,technological improvements, an economy growth ofthepublicsector, consider with two and healthcare,increase lifeexpectancy and production sector sectors, private (P) and public(G). The private pays lead to theemergence of healthinstitutions and pension a taxr. forG through fortheelder. systems in bothsectors. In thepublicsecProductivities differ Economicdevelopment does not mechanically lead theproductivity andoutput attime oflaboris constant, tor, to largerpublic sectors.Taxes and expenditure are set = t is YGt aLGt,where is thequantity oflaboremployed LGt through a political mechanism,wherebypoliticians at timetand a is a constant. in theprivate secBycontrast, matchthepreferences oftheenfranchised. As a result, retor the productivity of labor growsat a constantcomdistributive on thepolitiprograms emergeconditional = bLpt ert, pounded rater,so thatat timet,outputis Ypt cal regimein place. In authoritarian regimes, generally where b is a constant. imposedto blockredistribution, or in democracies with and Wt at Wt, Wagesareequal in thetwosectors grows in low levelsof turnout, taxes remainlow. Conversely, in accord with theproductivity oftheprivate sector, so that democratic thepublicsectorgrowsas modernregimes, withWequalto someconstant. Wt= Wert, izationshifts theunderlying distribution of interests toCosts. As a result ofproductivity Divergent differentials, wardthedevelopment ofbothintragenerational and,esthecostsin each sector Totalcostsfortheprivate diverge. transfers. pecially, intergenerational and thepublicsector are,respectively: Within democratic electoral turnout regimes, playsa rolein boosting thesize ofthepublicsector. As powerful CP = WtLpt = Wert Lpt redistributive tenparticipation goes up, the underlying CG= WtLG= WertLGt sions effectively forcepoliticiansto expand public proconstitutionalarrangegrams. By contrast,different unitcostsare: whichhad been claimedto be central in themost Theirrespective ments, recent have a marginal effect on comparative literature, = WI the size of the state.Presidential deb systems generally Lpt Ypt) = (Wert Lpt bLpt ert) cp= (Wert ) = pressthelevelof government revenues. Butboth federal CG (WertLtY-t) = (WertLt laLct Wert la

Remarks Concluding

This content downloaded by the authorized user from 192.168.72.230 on Mon, 19 Nov 2012 15:19:50 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

16

CARLES

BOIX

So, whereasP's unitcostsremainconstant, G's unitcost grow atthecompounded rater. IfthedemandforG'soutG as a Shareofthe Economy. putis inelastic, thenYG = YG.Assume that theportion that willbe given P willspend(through T) to satisfy this demand ofG divided bythecostoftheproduction bythecostofthe production ofP (thetotalcostof Ypwillbe equalto thetotalvaluein a competitive market):

T = YGCG

Ypcp

theterms and solving itis posthisexpression, Substituting G an that the as of sibleto show of effort P does proportion notchange fora fixed demandofpublicservices and wage increases of theprivate increases equal to theproductivity sector:

aLG(Wertla) - LGt ert (W/b) Lpt bLpt

(1953-54, 1960-90), Japan (1950-90), Jordan (1959-63, 1983-86), Korea (1953-90), Malaysia (1960-67, 1969-73), Myanmar (1950-63), Philippines (1951-90), Singapore (1960-69), Sri Lanka (1970-90), Taiwan (1951-63), Thailand (1965-90), Yemen (1972-73), Austria (1950-90), Belgium (1950-88), Denmark (1950-58, 1960-90), Finland (1954-89), France (1950-90), West Germany (1950-56, 1960-90), Greece (1950-88), Iceland (1965-68, 1970-90), Ireland (1950-90), Italy(1955-90), Luxembourg(1952-86), Malta (1954-60,1965-89), Netherlands(1950-90), Norway (1951-90), Portugal (1952-89), Spain (1954-90), Sweden (1950-89), Switzerland (1955-90), Turkey (1965-72), United Kingdom (1950-90), Australia(1950-60, 1965-90),

Fiji(1977-89),NewZealand(1950-65),PapuaNewGuinea (1965-72),SolomonIslands (1984-86), Vanuatu (1983-89).

References

Parties, 1995.Political Alesina, Aberto, and Howard Rosenthal. and theEconomy. Cambridge:CamDivided Government, Press. bridgeUniversity and AntonioCheibub,FernandoLimongi, Alvarez, Mike,Jose Political Regimes." Adam Przeworski.1996. "Classifying 31:3-36. International Development Studies in Comparative 1983. PoliticalEconomics. Alt,James E., and K. Alec Chrystal. of California Press. Berkeley: University Baumol, William J.1967. "Macroeconomics of Unbalanced of theUrban Crisis." American EcoGrowth: The Anatomy 57: 415-426. nomic Review N. Katz.1995."Whatto Do (and Beck,Nathaniel, and Jonathan Data."American Cross-Section Not to Do) withTime-Series 89: 634-647. Political Science Review Unpublished Boix, Carles.2000. "Democracyand Inequality." The University of Chicago. manuscript. Cameron, David R. 1978. "The Expansion of the Public Political SciAnalysis." American Economy:A Comparative enceReview 72:1243-1261. Cheibub,JoseAntonio. 1998. "PoliticalRegimesand the Exin Democracies Taxation ofGovernments: tractive Capacity World Politics 50:349-376. and Dictatorships." Coordination Count:Strategic Cox, GaryW. 1997.MakingVotes New York:Cambridge Uniin theWorld's Electoral Systems. Press. versity EconomicDevelCutright, Phillips.1965."PoliticalStructure, American Programs." opmentand nationalSocial Security 70:537-550. Journal ofSociology Deininger, Klaus,and LynSquire.1996."A New Data Set MeaThe World Bank EconomicResuringIncome Inequality." view19:565-591. 2000. "Federalismand EthnicConflict." Downes, Alexander. The University of Chicago. Mimeograph. of Welfare G6sta. 1990. The ThreeWorlds Esping-Andersen, Press. Cambridge: Polity Capitalism. and JanAlber.1981."Modernization, DemocratiFlora,Peter, Statesin Western zation and the Developmentof Welfare

in thepublicsector, In short, although laborcostsincrease theshareof G as a proportion of theavailableresources doesnotincrease.

APPENDIX B Sample

Algeria (1970-79), Benin(1965-67), Botswana(1967-68, 1973-87), Cameroon (1974-87), Congo (1980-88), Djibouti(1979-80), Gabon (1974-78), Ghana (1955-59), Coast (1970-79),Lesotho Guinea-Bissau (1986-87),Ivory (1972-83), Malawi (1973-82), Mali (1981-82), Mauritius Morocco(1951-54),Niger(1975-77), (1950-63,1969-90), Leone (1963-64,1985Nigeria (1952-60,1963-68),Sierra Sudan South Africa 90), (1950-90), (1970-71, 1980-83), Swaziland(1967-72,1980-88),Togo (1963-64,1970-72), Tunisia (1965-90), Zaire (1950-59), Zambia (1955-63, Zimbabwe Barbados 1967-73), (1954-59,1965-89), (196063), Canada (1950-89), Costa Rica (1950-60, 1965-90), Dominican Republic (1968-69), Guatemala(1955-63), Honduras (1950-85),Jamaica (1953-89),Nicaragua (196578), Panama (1952-70, 1973-90), Trinidadand Tobago (1951-62, 1975-90),UnitedStates(1950-90), Argentina

(1973-80), Bolivia (1958-63, 1965-69, 1980-86, 1988-90),

Brazil (1973-74, 1980-89), Chile (1950-76), Colombia

(1951-63,1965-71,1973-90), Ecuador (1950-63,1970-78,

1980-90),Guyana(1955-56, 1960-63),Paraguay (197090), Peru(1951-58, 1965-90),Suriname (1972-75),Uruguay(1955-63, 1980-90),Venezuela(1960-65, 1970-75, 1978-90),India(1950-57,1960-90),Iran(1973-90),Israel

This content downloaded by the authorized user from 192.168.72.230 on Mon, 19 Nov 2012 15:19:50 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

DEMOCRACY,

DEVELOPMENT,

AND THE PUBLIC

SECTOR

17

In TheDevelopment in Europe and ofWelfare States Europe." New America, ed. PeterFlora and ArnoldJ.Heidenheimer. Transaction Books. Brunswick, N.J.: In Compar"Electoral Participation." Franklin, MarkN. 1996. and Voting in GlobalPerspective, Elections ingDemocracies. ed. LawrenceLeDuc, RichardG. Niemi,and Pippa Norris. ThousandOaks: Sage. IncomeDistriParticipation, Franzese, Robert.1998."Political in Developed Democracies." bution,and Public Transfers Presented at theAnnual Meetingof theAmericanPolitical ScienceAssociation. InDwane H. 1992."Politics, Hicks,Alexander M., and Swank, in Industrialized Democraand Welfare Spending stitutions PoliticalScienceReview86:658cies, 1960-82." American 674. 1997. "Why Holsey,CherylM., and Thomas E. Borcherding. Does Government's Share of National Income Grow?An Literature on theU.S. Experience. Assessment oftheRecent ed. Dennis C. A Handbook, In Perspectives on PublicChoice: Mueller. NewYork:Cambridge. 1993."Social Democracy, Huber,E., C. Ragin,and J.Stephens. ChristianDemocracy,ConstitutionalStructureand the Welfare State." American 99:711-749. Journal ofSociology IDEA. 1997. Voter Turnout from1945 to 1997:A GlobalReport on Political Stockholm: International Institute Participation. forDemocracyand Electoral Assistance. Yearbook. Finance Statistics IMF. SeveralYears. Government D.C.: IMF. Washington Robert W. 1975.Politics and Social Equality: A ComJackman, NewYork: Wiley. parative Analysis. in theDePolitics and StateAutonomy Korpi, W, 1989."Power, duringSickSocial Rights velopment of Social Citizenship: ness in EighteenOECD Countriessince 1930s."American Review 54:309-328. Sociological Gov1990. Multiparty Laver, Michael,and NormanSchofield. Press. ernment. New York:Oxford University Valenzuela.1994. TheFailureofPresiand Arturo Linz,Juan J., Bal1: Comparative Democracy. Volume dential Perspectives. Press. The Johns timore: HopkinsUniversity Lybeck,JohanA. 1988. "Comparing GovernmentGrowth Rates: The Non-Institutional vs. the InstitutionalAped. Johan In Explaining theGrowth ofGovernment, proach." Amsterdam: North-Holand MagnusHenkerson. A. Lybeck land. and SocialDevelopment. T.H. 1963.Class,Citizenship, Marshall, of ChicagoPress. Chicago:The University Meltzer, A.H., and S. F. Richards.1981."A RationalTheoryof the Size of Government."Journalof Political Economy 89:914-927.

IL Cambridge: Cambridge Mueller, Dennis. 1988.PublicChoice Press. University 1971. Bureaucracy and Representative Niskanen, WilliamA. Jr. Atherton. Chicago:AldineGovernment. and DevelopDemocracy, Olson,Mancur.1993."Dictatorship, Science Review 87:567-576. ment." American Political Spendingin J.B.1988."Welfare Pampel,F.C.,and Williamson, Advanced Industrial Democracies, 1950-80." American 93:1424-1456. Journal ofSociology ofPublicExWiseman.1961. The Growth Peacock, A. T.,and J. in theUnited UniPrinceton Kingdom. Princeton: penditure versity Press. Persson,Torsten, and Guido Tabellini. 1998. "The Size and Comparative PoliticswithRational Scope of Government: Mimeograph. BocconiUniversity. Politicians." RePrzeworski, Adam,and FernandoLimongi.1993."Political PerspecJournal ofEconomic gimesand EconomicGrowth." tives 7:51-69. Przeworski, Adam,and FernandoLimongi.1997."Modernization:Theoriesand Facts."World Politics 49:155-183. Ram, Rati. 1987. "Wagner'sHypothesisin Time-Seriesand Evidencefrom "Real" Data for Cross-Section Perspectives: 115 Countries." ReviewofEconomics and Statistics 69:194204. Rodrik,Dani. 1996. "WhyDo Open Economies Have Bigger Governments?" NBER Working Paperno. 5537. StevenJ., and John MarkHansen. 1993.MobilizaRosenstone, in America. New York: and Democracy tion,Participation, Macmillan. Shepsle,KennethA., and BarryR. Weingast.1981. "Political A Generalization." American Preferences forthePorkBarrel: Science 25:96-111. Journal ofPolitical M. Carey.1992. Presidents and MatthewS., and John Shugart, Assemblies. Constitutional Dynamics. Design and Electoral Press. New York: Cambridge University on theWelfare State. London:Allenand R. 1958.Essays Titmuss, Uwin. and reprinted A. 1883.Finanzwissenschaft. Translated Wagner, as "Three Extractson Public Finance."In Classicson the Theory ofPublicFinance,ed.R.A. Musgraveand A.T. Peacock.London:Macmillan. BerStateand Equality. Harold L. 1975. The Welfare Wilensky, Press. of California keley: University New World Bank. Severalyears. WorldDevelopment Report. Press. York:Oxford University United Nations. Several years. UnitedNations National Accounts. NewYork:UN.

This content downloaded by the authorized user from 192.168.72.230 on Mon, 19 Nov 2012 15:19:50 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Cuenta Palabras Eu DC Exit Os AsDocument72 pagesCuenta Palabras Eu DC Exit Os AsDiego Ignacio Córdova MolinaNo ratings yet

- Held, "Democracia Deliberativa" (Selección)Document4 pagesHeld, "Democracia Deliberativa" (Selección)Diego Ignacio Córdova MolinaNo ratings yet

- Jeremy Waldron. Cap.V PDFDocument19 pagesJeremy Waldron. Cap.V PDFDiego Ignacio Córdova MolinaNo ratings yet

- Names: Keren Moran Nathaly Ramirez Camila Jara Martina ZúñigaDocument9 pagesNames: Keren Moran Nathaly Ramirez Camila Jara Martina ZúñigaDiego Ignacio Córdova MolinaNo ratings yet

- Bandas Bajar TemasDocument1 pageBandas Bajar TemasDiego Ignacio Córdova MolinaNo ratings yet

- Press Release: Date Grand Prix CircuitDocument1 pagePress Release: Date Grand Prix Circuitwear3333No ratings yet

- 70467229Document23 pages70467229Diego Ignacio Córdova MolinaNo ratings yet

- Curinga 2009 Ranciere Free EncyclopediaDocument8 pagesCuringa 2009 Ranciere Free EncyclopediaDiego Ignacio Córdova MolinaNo ratings yet

- Rummens, Stefan. Staging DeliberationDocument23 pagesRummens, Stefan. Staging DeliberationDiego Ignacio Córdova MolinaNo ratings yet

- Political PhilosophyDocument333 pagesPolitical PhilosophyDiego Ignacio Córdova Molina96% (24)

- Bowles and GintisDocument10 pagesBowles and GintisDiego Ignacio Córdova MolinaNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)