Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Liberalism and Republicanism Friends or Foes A Reply To Richard Dagger Michael J. Sandel

Uploaded by

relic29Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Liberalism and Republicanism Friends or Foes A Reply To Richard Dagger Michael J. Sandel

Uploaded by

relic29Copyright:

Available Formats

Liberalism and Republicanism: Friends or Foes? A Reply to Richard Dagger Author(s): Michael J.

Sandel Reviewed work(s): Source: The Review of Politics, Vol. 61, No. 2 (Spring, 1999), pp. 209-214 Published by: Cambridge University Press for the University of Notre Dame du lac on behalf of Review of Politics Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1408354 . Accessed: 15/12/2012 18:11

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Cambridge University Press and University of Notre Dame du lac on behalf of Review of Politics are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Review of Politics.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded on Sat, 15 Dec 2012 18:11:12 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Liberalism and Republicanism: Friends or Foes? A Reply to Richard Dagger

Michael J. Sandel

I am grateful to Professor Dagger for his insightful critique. He brings out the continuities and differencesbetween Democracy's Discontentand my earlier work with subtlety and care. He writes in defense of liberalism, but not without sympathy for many of the ideals I invoke in the name of republicanism-civic virtue, encumbered selves, obligations of membership, the formative project. In fact, his republican sympathies are so expansive that I found myself unsure at times whether I could identity a fundamental disagreement. Professor Dagger's basic objection, as I understand it, is this: I overstate the opposition between liberalism and republicanism, between autonomy and civic virtue; in drawing these distinctions too sharply, I fail to acknowledge the elements of liberalism I implicitly affirm. Professor Dagger accepts the importance of civic virtue and the formative project. But he considers it a mistake to oppose liberalism as vigorously as I do, and "particularlywrong to oppose republicanismto liberalism." Instead,he favorsa "hybrid" of liberalism and republicanismthat combines autonomy and civic virtue. Any republicanism worth defending must include "a commitment to liberal principles, such as tolerance, fair play, and respect for the rights of others." Whetherliberalismand republicanismarecompatibledoctrines depends on how they are conceived. At a certain level of generality, there is no necessary conflict: the liberal tradition stands for toleration and individual rights, while the republican tradition stands for government by the people. Liberal rights support republican self rule by preventing the majority from oppressing the minority, while the republican emphasis on civic virtue restrains individualsfromabusingtheirrightsand ignoringthe common good. This is the compatibilist account that Professor Dagger favors, and it is unobjectionable as such. What, then, is the point of specifying the two traditions in a way that highlights the tension

This content downloaded on Sat, 15 Dec 2012 18:11:12 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

210

THE REVIEWOF POLITICS

between them? Why pick a fight with liberals "who otherwise might be persuaded to see how their own commitments require them to accordgreatervalue and attentionto republicanprinciples"?

Procedural versus Perfectionist Liberalism

As Professor Dagger observes, my quarrel is not with liberalism as such but with the procedural liberalism prominent in the academy and in the political discourse of our time. This is the liberalism that insists government should be neutral toward competing conceptions of the good life, or, in the philosophers' parlance, the liberalism that asserts the priority of the right over the good. My objection to this liberalism is not that it emphasizes individual rights but that it seeks to define and defend rights without affirming any particular conception of the good life. The reason for focusing on this version of liberalism is not that it is weak and hence an easy target but that it is philosophically attractive and politically influential. Its moral and political appeal can be understood in two ways: First, in pluralist societies such as ours,people often disagreeon moraland religiousquestions. It is therefore tempting to seek principles of justice that do not depend for their justification on any particular moral or religious conception. Second, for government to affirm in law some particular vision of the good life seems a kind of coercion; it fails to respectpersons as free and independent selves, capableof choosing their own values and ends. The very features of procedural liberalism that make it attractive call into question the formative project of the republican tradition. The formative project rejects the idea that government should be neutral toward the values and ends its citizens espouse. It seeks social and political arrangementsthat cultivate in citizens certain habits and dispositions, or civic virtues. Ratherthan affirm above all the capacity of persons to choose their own ends, the republican tradition accords the political community an explicit stake in the moral character of its citizens. It makes character a public, not merely private concern. Some (including Professor Dagger) might reply that the formative project is not necessarily inconsistent with liberal ideals. This defense of liberalism comes in two versions. One adheres to the priority of the right over the good, but allows for those virtues

This content downloaded on Sat, 15 Dec 2012 18:11:12 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

LIBERALISMAND REPUBLICANISM

211

that support it-such as toleration, civility, and respect for the rights of others.'Another abandons proceduralliberalismfor some version of perfectionist liberalism. It gives up the aspiration to neutrality and promotes liberal virtues like autonomy and individuality as comprehensive moral ideals, qualities of character that figure prominently in the good life.2 Procedural liberalism contrasts more sharply with republicanism than does perfectionist liberalism. The reason is that procedural liberalism imposes heavy restrictionson the formative project. It rejects all civic virtues whose justification depends on comprehensive moral ideals. Consider, for example, the case of consumerism. Republicansmight seek to discourage practicesthat glorify consumerism on the grounds that such practices promote privatized, materialistic habits, enervate civic virtue, and induce a selfish disregard for the public good. The republican tradition has long regarded an excessive preoccupation with consumption to be a moral and civic vice, inimical to self government. For procedural liberals, by contrast, policies designed to discourage consumerism can only be justified insofar as the preoccupation with material things undermines support for principles of justice. Any attempt to regulate consumerism or materialism on other grounds would impermissibly infringe people's right to choose their values for themselves. The quarrel between perfectionist liberals and republicans is of a different kind. At issue is not whether to affirm in law a particular conception of the good life, but what conception-or range of conceptions-is most desirable. Given their emphasis on autonomy and individuality as moral ideals, perfectionist liberals might join republicans in a campaign to reduce the hold of consumerism on the public culture. Their reasons might have

1. This view is present in John Rawls, A Theoryof Justice(Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1971), and in Rawls, Political Liberalism (New York: Columbia University Press, 1993). For an illuminating discussion of this point, see Will Kymlicka, "LiberalEgalitarianismand Civic Republicanism:Friends or Enemies?," in Anita L. Allen and Milton C. Regan, Jr., Debating Democracy's Discontent(Oxford:Oxford University Press, 1998), pp. 131-48. 2. The liberalism of John Stuart Mill is perhaps the most familiar example. and Contemporaryexamples include George Kateb, TheInnerOcean: Individuality Democratic Culture(1992),and Joseph Raz, TheMoralityofFreedom (Oxford:Oxford University Press, 1986).

This content downloaded on Sat, 15 Dec 2012 18:11:12 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

212

THE REVIEWOF POLITICS

nothing to with the effects of consumerism on justice and rights (as procedural liberals would require), nor with its consequences for self-government (as republicans would emphasize), but instead with the aim of combating conformity and complacency as defects of character. One reason for posing the distinction between liberalism and republicanism as starkly as I do is to force liberals to choose between their procedural and perfectionist impulses. It is not clear to me which version of liberalism ProfessorDagger favors, though his willingness to jettison neutrality suggests the second. In any case, perfectionist liberalism seems a more plausible candidate for the liberal republican "hybrid"he hopes to fashion. Once character formation for the sake of substantive moral and civic ideals is accorded legitimacy, citizens can debate which virtues their political community should cultivate and prize. Republicans and perfectionist liberals may agree on some virtues and disagree on others, but they share the notion that political arrangements should be judged by the kind of citizens they produce.

Two Concepts of Autonomy

According to Professor Dagger, the most important liberal contribution to a liberal-republican hybrid is the ideal of autonomy, a value he thinks I wrongly associate with procedural liberalism and the unencumbered self. Autonomy and civic virtue might seem to be opposites, he observes, because autonomy points to individual claims and civic virtue to communal ones; but in fact they are complementary principles, since each remedies the excesses of the other and together they remind us of our interdependence. I do not agree that the concept of autonomy offers a necessary supplement to republican ideals of liberty and independence. Contemporary liberals often invoke it, but there are two different senses of autonomy, and it is important to distinguish them. One sense refersto individual choice. People are said to be autonomous when they can live their lives as they please, according to their own desires, without undue interference by the state or other agencies of power. This is the sense of autonomy that Professor Dagger seems to have in mind when he refers to "personal autonomy," with its "individualistic" bent. But there is another,

This content downloaded on Sat, 15 Dec 2012 18:11:12 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

LIBERALISMAND REPUBLICANISM

213

more demanding notion of autonomy that has nothing to do with acting according to one's own individual preferences and desires. According to Kant, to act autonomously is to act according to a law I give myself-to act, that is, according to the categorical imperative. Kant emphasizes that, insofar as I act autonomously, I do not act out of my particularpreferences and desires but rather as a participant in pure practical reason, as a universal subject. This is what guarantees that the moral law is not just up to us, as individuals, to decide-one principle for you, another for me. Contemporary liberals draw sometimes on the Kantian sense of autonomy, sometimes on the individualistic sense. The reason I associate autonomy with procedural liberalism and the unencumbered self is that the claim for the priority of the right over the good is a Kantian claim. The idea that we should think about justice from the standpoint of persons who abstract from their particular interests and ends expresses the ideal of autonomy in the Kantian sense. For the most part, Professor Dagger employs the concept of autonomy in its individualistic sense. The "personal autonomy" of which he writes is, from a Kantian point of view, an oxymoron. Once personal considerations or particular circumstances determine the will, the choice is not autonomous but heteronomous. Nor would Kant agree with Professor Dagger that "it is possible for an autonomous person to act in a thoroughly selfish manner." Toact out of selfish motivations is, for Kant,to act heteronomously, not autonomously. A selfish act can be an autonomous act only in the non-Kantian, individualistic sense of autonomy. How, then, can the concept of autonomy cure the defects of republicanism? It might be thought that autonomy in its individualistic sense can remedy the coercive, collectivist tendencies to which republicanism is prone; the idea that individuals should be free to act according to their preferences within certain spheres of life might be seen as a sensible liberal restraint on the formative project. But despite his frequent references to "personal autonomy," this is not the "hybrid" Professor Dagger has in mind. Instead, to establish the link between autonomy and civic virtue, he turns to Rousseau, for whom freedom is only possible when the general will of the citizen takes precedence over the particular will of the individual. Professor Dagger rightly notes the close connection between

This content downloaded on Sat, 15 Dec 2012 18:11:12 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

214

THE REVIEWOF POLITICS

Rousseau's idea of freedom and Kantian autonomy. Rousseau's general will, like Kant's autonomous will, locates freedom in a moment that abstracts from all particularity. Neither endorses sense familiar among autonomy in the individualistic liberals. contemporary Even admirers of Rousseau worry about the coercion to which the general will is prone and especially his suggestion that people can be forced to be free. This dark side of Rousseau is often attributed to an excess of republicanism. In fact, however, what makes Rousseau's politics dangerous is not its republican commitment to civic virtue but rather its assumption that the general will is unitary and undifferentiated; political deliberation is impossible because, according to Rousseau, any disagreement signals the corruption of the general will by particular interests. The unitary, undifferentiated character of the general will is bound up with the idea that moral freedom consists in abstracting from all particular interests, ends, and conceptions of the good. And this ideal of unsituated freedom is precisely what Kant takes from Rousseau and turns into the concept of freedom as autonomy. So a "hybrid" of civic virtue and autonomy in the Kantian sense does not diminish the dangers of the formative project but if anything compounds them. What, then, of autonomy in the individualistic sense? Should the scope of public deliberation be constrained in advance so that individuals may be free to act according to their own preferencesand desires, at least within certain spheres of life? The answer, it seems to me, depends on the moral importance of the preferences and desires in question compared to the moralimportanceof the public purposes thatwould challenge or override them. This is no argument against individual rights. It is simply to insist that arguments for rights cannot be detached from substantive moral judgments about the purposes and ends rights advance.

This content downloaded on Sat, 15 Dec 2012 18:11:12 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Using Vygotsky S Zone of Proximal Development To Propose and Test An Explanatory Model For Conceptualising Coteaching in Pre Service Science TeacherDocument16 pagesUsing Vygotsky S Zone of Proximal Development To Propose and Test An Explanatory Model For Conceptualising Coteaching in Pre Service Science Teacherrelic29No ratings yet

- Analytic Final 4Document4 pagesAnalytic Final 4relic29No ratings yet

- Did Michael Sandel Completely Misunderstand The Basics of Justice in Rawls or Is He After Something ElseDocument12 pagesDid Michael Sandel Completely Misunderstand The Basics of Justice in Rawls or Is He After Something Elserelic29100% (1)

- Rejoinder To Michael Sandel Richard DaggerDocument4 pagesRejoinder To Michael Sandel Richard Daggerrelic29No ratings yet

- The Political Theory of The Procedural RepublicDocument13 pagesThe Political Theory of The Procedural Republicrelic29No ratings yet

- HTTP Shemer - Mslib.huji - Ac.il ReferDocument12 pagesHTTP Shemer - Mslib.huji - Ac.il Referrelic29No ratings yet

- Examples in EpistemologyDocument19 pagesExamples in Epistemologyrelic29No ratings yet

- Negativity and Difference On Gilles Deleuze's Criticism of DialecticsDocument26 pagesNegativity and Difference On Gilles Deleuze's Criticism of Dialecticsrelic29No ratings yet

- The Political Theory of The Procedural RepublicDocument13 pagesThe Political Theory of The Procedural Republicrelic29No ratings yet

- The Value of ReligionDocument19 pagesThe Value of Religionrelic29No ratings yet

- The Ultimate Origin of ThingsDocument7 pagesThe Ultimate Origin of ThingsscribdballsNo ratings yet

- Nordgren Visceral Drives in RetrospectDocument6 pagesNordgren Visceral Drives in Retrospectrelic29No ratings yet

- Nietzsche's Doctrine of Eternal ReturnDocument36 pagesNietzsche's Doctrine of Eternal Returnrelic29No ratings yet

- 4106413Document36 pages4106413relic29No ratings yet

- 2376402Document31 pages2376402relic29No ratings yet

- Deleuze's Nietzsche and Post-Structuralist ThoughtDocument18 pagesDeleuze's Nietzsche and Post-Structuralist Thoughtrelic29No ratings yet

- Freedom and Resentment - Peter Strawson PDFDocument12 pagesFreedom and Resentment - Peter Strawson PDFrelic29No ratings yet

- Deleuze's Nietzsche and Post-Structuralist ThoughtDocument18 pagesDeleuze's Nietzsche and Post-Structuralist Thoughtrelic29No ratings yet

- Lectures On Freedom of Will - Ludwig Wittgenstien PDFDocument10 pagesLectures On Freedom of Will - Ludwig Wittgenstien PDFrelic29No ratings yet

- The Dilemma of Determinism - William James PDFDocument21 pagesThe Dilemma of Determinism - William James PDFrelic29No ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Learning Organization - How Planners Create Organizational Learning PDFDocument11 pagesThe Learning Organization - How Planners Create Organizational Learning PDFvlademiroNo ratings yet

- Pop culture's influence on career aspirationsDocument3 pagesPop culture's influence on career aspirationsHubert John VillafuerteNo ratings yet

- Job Satisfaction of Employee and Customer Satisfaction: Masoud Amoopour, Marhamat Hemmatpour, Seyed Saeed MirtaslimiDocument6 pagesJob Satisfaction of Employee and Customer Satisfaction: Masoud Amoopour, Marhamat Hemmatpour, Seyed Saeed Mirtaslimiwaleed MalikNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1Document3 pagesLesson 1api-243046468100% (1)

- Sons and LoversDocument4 pagesSons and LoversxrosegunsxNo ratings yet

- Lesson PlanDocument2 pagesLesson Planapi-261245238No ratings yet

- Learning Segment Lesson Plans PDFDocument7 pagesLearning Segment Lesson Plans PDFapi-249351260No ratings yet

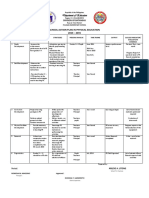

- Department of Education: School Action Plan in Physical Education 2014 - 2015Document3 pagesDepartment of Education: School Action Plan in Physical Education 2014 - 2015Miriam Haber BarnachiaNo ratings yet

- Sex and SexualityDocument22 pagesSex and Sexuality吴善统No ratings yet

- Stale QueenDocument3 pagesStale Queenapi-283659700No ratings yet

- 7 Qualities of LeadershipDocument7 pages7 Qualities of LeadershipOmkar SutarNo ratings yet

- Gormally 1982Document9 pagesGormally 1982lola.lmsNo ratings yet

- Myths and Realities About WritingDocument4 pagesMyths and Realities About Writingrizwan75% (4)

- Building a Moral Nation Through Understanding Filipino CharacterDocument19 pagesBuilding a Moral Nation Through Understanding Filipino CharacterJade Harris' SmithNo ratings yet

- mcs-015 Study MaterialsDocument171 pagesmcs-015 Study Materialshamarip111No ratings yet

- Debriefing in Healthcare SimulationDocument9 pagesDebriefing in Healthcare Simulationchanvier100% (1)

- Coursera SoftSkills EbookDocument13 pagesCoursera SoftSkills Ebooktimonette100% (1)

- Victor R. Baltazar, S.J. Student ProfessorDocument7 pagesVictor R. Baltazar, S.J. Student ProfessorDagul JauganNo ratings yet

- Outline For Capstone Project 2015Document2 pagesOutline For Capstone Project 2015Angelo DeleonNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan: Pre-Instructional PlanningDocument10 pagesLesson Plan: Pre-Instructional PlanningBenturaNo ratings yet

- MGT502 Midterm 5-PapersDocument44 pagesMGT502 Midterm 5-PapersHisham AbidNo ratings yet

- Bayo, HanzatDocument103 pagesBayo, HanzatJudeNo ratings yet

- Activity 1 - EmojiDocument3 pagesActivity 1 - Emojiapi-348062732No ratings yet

- Teenagers' Relationship With Their ParentsDocument5 pagesTeenagers' Relationship With Their ParentsAnonymous ifheT2Yhi100% (1)

- Richard Morrock The Psychology of Genocide and Violent Oppression A Study of Mass Cruelty From Nazi Germany To Rwanda 2010Document263 pagesRichard Morrock The Psychology of Genocide and Violent Oppression A Study of Mass Cruelty From Nazi Germany To Rwanda 2010Matt Harrington100% (4)

- Trauma and Life StorysDocument267 pagesTrauma and Life StorysCarina Cavalcanti100% (3)

- Multicultural Experience Enhances Creativity: The When and HowDocument13 pagesMulticultural Experience Enhances Creativity: The When and HowMaiko CheukachiNo ratings yet

- PES P6 New With No Crop MarkDocument215 pagesPES P6 New With No Crop MarkAnonymous xgTF5pfNo ratings yet

- 7TH Grade Life ScienceDocument85 pages7TH Grade Life SciencejamilNo ratings yet

- Quarter 2 3: Disciplines and Ideas in The Applied Social SciencesDocument5 pagesQuarter 2 3: Disciplines and Ideas in The Applied Social SciencesCHARLENE JOY SALIGUMBANo ratings yet