Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Buddhism in The Sung

Uploaded by

moorgiftOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Buddhism in The Sung

Uploaded by

moorgiftCopyright:

Available Formats

ISSN 10769005 Journal of Buddhist Ethics 8 (2001): 75-77

Buddhism in the Sung

Edited by Peter N. Gregory and Daniel A. Getz Reviewed by Michael J. Walsh

Department of Religion Vassar College

miwalsh@vassar.edu

Copyright Notice

Digital copies of this work may be made and distributed provided no change is made and no alteration is made to the content. Reproduction in any other format with the exception of a single copy for private study requires the written permission of the author. All enquiries to jbe-general@jbe.la.psu.edu

Buddhism in the Sung is a collection of essays from well-known scholars in the field of Buddhist

studies. There are a total of thirteen essays presented as thirteen chapters. The end of the volume includes useful glossaries of names, terms, and texts. These essays are based on papers delivered at a conference on Buddhism in the Song held at the University of Illinois in April 1996. It is fair to say, as the editors of this fine text are at pains to point out, that the impact of Buddhism on Song dynasty China is seriously understudied. We have little research in any Western language that can help us better understand Buddhism's impact on local society and culture during the tenth to thirteenth centuries. This book does much to redress this imbalance. As Peter Gregory in the first essay explains, there exists in China studies today a stereotype of the Tang dynasty being the cultural height of Chinese Buddhist development, whereas the Song period saw Buddhism's decline. This is simply not the case, and each contributor to this volume demonstrates the falseness of this stereotype. Buddhism flourished during the Song dynasties, and it did so in a number of creative ways. Generally speaking, Chan and Tiantai were the two dominant Buddhist traditions during the Song period, although several of the essays point out the difficulty in clearly articulating sectarian identities. What follows is a brief summary of each essay, with two points of mine at the end of the review. First, Albert Welters's essay looks at Zanning (919-1001), whose voice joined in the early Song debates over what constituted wen, "culture." Zanning argued that Buddhism ought to be a component of the wen revival. Zanning's proposals were ultimately rejected by wen officials, but Welter's focus on Zanning's arguments highlights the complex relations between officials and Buddhist elite at the time. In chapter three, Ari Borrell draws our attention to the relationship between Neo-Confucianism and Buddhism by focusing on the works of Zhang Jiucheng (1092-1159), a lay disciple of the Chan Master Dahui (1089-

Journal of Buddhist Ethics 8 (2001): 75

JBE Online Review

1163) and an advocate of daoxue (learning of the way). Zhu Xi (1130-1200) strongly criticized Zhang, thereby acknowledging the impact Zhang was having on daoxue. Morten Schltter's essay in chapter four raises questions about the supposed debates between Dahui (Linji sect) and Hongzhi (1091-1157) of the

Caodong sect. Dahui strongly advocated gong'an investigations and criticized Hongzhi's "Silent

Illumination of Chan." Schltter clearly demonstrates that we must understand the conflict between these two major Buddhist figures in the context of their respective schools competing for lay patronage. By the Southern Song (1127-1279), the imperium had withdrawn much support from Chan monasteries, thus forcing these institutions to look for other patrons. Schltter moves us away from a strict soteriological framework and places more emphasis on the importance of local context. In chapter five, Ding-Hua E. Hsieh looks at the images of women in Chan literature (such as genealogical histories, public case anthologies, and discourse records). The issue at hand is women's supposed lack of spirituality because of the nature of the female body. Chan, to some extent, offered a way around this old Buddhist problem by arguing that all persons have Buddha-mind. Hsieh shows just how far this argument can be taken and highlights the limitations of such a context for women in the Chan tradition. Miriam Levering, in chapter six, follows up on Hsieh's arguments by focusing attention on one of Dahui's female students, Miaodao (1095-1170). T. Griffith Foulk's essay, in keeping with his earlier research, shows the ideology, indeed mythology, of Chan as a "separate transmission." Claims to lineage were a crucial component of Song dynasty Chan, and debates raged over what constituted legitimate transmission and lineage. Foulk looks at an array of doctrinal arguments and clearly makes his case. Chapter eight, by Chi-Chiang Huang, focuses on the impact of prefects commissioned to Hangzhou during the Northern Song period. Huang shows how these prefects played an important role in creating climates for Buddhist centers in the eleventh century. Prefects enlisted the help of eminent monks in their efforts to maintain social control. Daniel B. Stevenson, in chapter nine, looks at Cun Shi (914-1032), a personality crucial to the revival of the Tiantai school of Buddhism. Stevenson highlights Cun Shi as a ritual specialist. He furthermore demonstrates the importance of ritual in understanding the relationship of Buddhist groups and local popular religious practices. In chapter ten, Chi-Wah Chan continues the focus on

Tiantai Buddhism by looking at the shanjia/shanwai (home mountain/off mountain) debates and arguing

that, by the end of the Southern Song, Zhili's (960-1028) Tiantai teachings constituted the dominant paradigm. Brook Ziporyn's essay provides further exploration of Zhili's Tiantai teachings and suggests the concept of "intersubjectivity" to better contextualize Zhili's arguments. Intersubjectivity here refers to "the imprint of the existence of other consciousness on the structure of any given consciousness." (p. 442) Daniel A. Getz Jr., in chapter twelve, draws our attention to the creation of a Pure Land patriarchate during the Song periods. Getz makes the case that such creations influenced Southern Song lay organizations by offering models of social organization. Finally, in chapter thirteen, Koichi Shinohara provides us with a study of Tiantai lineage construction and the emphasis placed on a Dharma heir. The author clearly demonstrates how, in part, this was a response of Tiantai sects to Chan's prioritization and construction of lineage. It is difficult to point out any weaknesses in this volume, as this is the first such study in English that we have of Song dynasty Buddhism as a social force. There are, however, two small points that can be made: First, future research might want to address the lack of focus on material culture in the history of Chinese Buddhism. The contributors' focus is still on elite traditions, principally because much of our

Journal of Buddhist Ethics 8 (2001): 76

Buddhism in the Sung

textual evidence comes from these traditions. However, there is much to be said for a more focused study of Buddhist material culture and the tremendous influence this had on Song society. For instance, scholars might want to look at land acquisition strategies by Buddhist monasteries, or the tax status of monastic institutions. More attention might be paid to the tremendous variety of economic processes Buddhist monasteries during the Song period were engaged in, such as operating mills, auctioning the robes of a deceased famous abbot, the production and sale of paper ink sticks and ink stones. Certain monasteries sold medicines. Other monasteries produced silk and sold it at a profit. Yet still others engaged in embroidery practices, produced lead powder, operated hostels, or made and sold food. It was quite common for larger Chinese Buddhist monasteries to establish oil presses to add to their overall income. To be fair to the authors of this volume, however, their primary focus is on doctrinal affairs and, as such, they are true to their aims. In short, the contribution of these collected essays opens wide avenues for further investigation. Perhaps then Buddhism's role in the shaping of Song dynasty Chinese society will be better appreciated. Second, more work ought to be done with the research of scholars writing in Chinese such as Zhang Mantao, Xie Zhongguang, Quan Hansheng, and Huang Min-Chih. These are only a few of the Chinese scholars who have done first-rate work on the more-mundane, material side of Buddhist economic activities during the Song period. Drawing more attention to material Buddhist culture would balance out the strict focus on doctrinal, philological, and philosophical concerns. However, the above two points are hardly serious criticisms, as the editors make it clear their focus is on doctrinal matters. In this respect, the editors and contributing scholars have done a remarkable job. No longer can Buddhism be said to "be in decline" during the Song periods.

Journal of Buddhist Ethics 8 (2001): 77

You might also like

- Nichiren’s Sangha Series Later Disciples: Kuonjo’in “Nabekanmuri” NisshinFrom EverandNichiren’s Sangha Series Later Disciples: Kuonjo’in “Nabekanmuri” NisshinNo ratings yet

- Nichiren Shoshu - ICHINEN SANZENDocument12 pagesNichiren Shoshu - ICHINEN SANZENJorge Alberto López GómezNo ratings yet

- Expanding "We Spaces" Narrowing the Management Paradox: An Explanation of We Space Theory by its OriginatorFrom EverandExpanding "We Spaces" Narrowing the Management Paradox: An Explanation of We Space Theory by its OriginatorNo ratings yet

- The Ten Oxherding Pictures Zen by Kakuan ShienDocument13 pagesThe Ten Oxherding Pictures Zen by Kakuan Shienoosh123No ratings yet

- Goldenlion Translation 華嚴金獅子章Document12 pagesGoldenlion Translation 華嚴金獅子章Vincent SungNo ratings yet

- Chih-I On Jneyavarana / Paul SwansonDocument23 pagesChih-I On Jneyavarana / Paul SwansonAadadNo ratings yet

- 1.1 NagarjunaDocument8 pages1.1 Nagarjunaallandzx100% (1)

- Salistamba SutraDocument37 pagesSalistamba SutraAadadNo ratings yet

- Bí Mật Của Bông Hoa Vàng - Cuốn Sách Đạo Giáo Trung Quốc Về Thiền (Richard Wilhelm) Thuviensach - VNDocument181 pagesBí Mật Của Bông Hoa Vàng - Cuốn Sách Đạo Giáo Trung Quốc Về Thiền (Richard Wilhelm) Thuviensach - VNTheta (Pham Cong Hieu)100% (2)

- Bokenkamp Stephen Simple Twists of Fate The Daoist Body and Its MingDocument27 pagesBokenkamp Stephen Simple Twists of Fate The Daoist Body and Its Mingtito19593No ratings yet

- The Secret of The Golden Flower 2 Research On The TextDocument2 pagesThe Secret of The Golden Flower 2 Research On The TextaaNo ratings yet

- The Writings of Nicherin DaishoninDocument2 pagesThe Writings of Nicherin DaishoninVishal MathyaNo ratings yet

- Bishop Hoeller: What Is AgnosticDocument7 pagesBishop Hoeller: What Is AgnosticOmorogah HagmoNo ratings yet

- Mary Finnigan & Rob Hogendoorn: "Sex and Violence in Tibetan Buddhism: The Rise and Fall of Sogyal Rinpoche" (2019, Jorvik Press)Document1 pageMary Finnigan & Rob Hogendoorn: "Sex and Violence in Tibetan Buddhism: The Rise and Fall of Sogyal Rinpoche" (2019, Jorvik Press)Rob HogendoornNo ratings yet

- Nagarjuna PrajnadandaDocument27 pagesNagarjuna PrajnadandaAlexandros PefanisNo ratings yet

- Kazi Dawa SamdrupDocument3 pagesKazi Dawa SamdrupLeki DorjiNo ratings yet

- Guifeng Zongmi-Inquiry Into The Origin of HumanityDocument20 pagesGuifeng Zongmi-Inquiry Into The Origin of HumanityKlaus Fischer100% (1)

- Chinese Philosophy Term Paper ZhuangZiDocument13 pagesChinese Philosophy Term Paper ZhuangZiJoshua Lanzon100% (1)

- CappingDocument777 pagesCappingEirini LomoNo ratings yet

- JWH-Sunyata and KenosisDocument19 pagesJWH-Sunyata and KenosisTimothy Smith100% (1)

- Evolas Nietzschean Ethics A Code of Conduct For The Higher Man in Kali YugaDocument17 pagesEvolas Nietzschean Ethics A Code of Conduct For The Higher Man in Kali Yugao2miQJLt4d4NJY2GNo ratings yet

- A Contextualization and Partial Annotated Translation of Xing Ming Gui Zhi Daniel Burton Rose PDFDocument254 pagesA Contextualization and Partial Annotated Translation of Xing Ming Gui Zhi Daniel Burton Rose PDFCornel Gabriel Pasare100% (3)

- CARLOS - Breathing ExercisesDocument2 pagesCARLOS - Breathing ExercisesCarlos De La GarzaNo ratings yet

- Hamvas Béla - Heloise and Abélard ENGDocument5 pagesHamvas Béla - Heloise and Abélard ENGhannorNo ratings yet

- Komatsu Kazuhiko - Bstudies On Izanagi-Ryū: A Historical Survey of Izanagi-Ryū Tayū (Hayashi Review)Document4 pagesKomatsu Kazuhiko - Bstudies On Izanagi-Ryū: A Historical Survey of Izanagi-Ryū Tayū (Hayashi Review)a308No ratings yet

- Chih I On Buddha NatureDocument12 pagesChih I On Buddha NatureJacob BargerNo ratings yet

- Tibetan Elephant Taming Picture SeriesDocument12 pagesTibetan Elephant Taming Picture Serieshumble626No ratings yet

- Beginnings by Ajahn SujatoDocument28 pagesBeginnings by Ajahn SujatoBhikkhu Jotika100% (1)

- Uji - The Time - Being by Eihei Dogen ZenjiDocument6 pagesUji - The Time - Being by Eihei Dogen Zenjidans100% (1)

- Diamond-Sutra ChiEngDocument77 pagesDiamond-Sutra ChiEngRidu YeNo ratings yet

- On Emptiness, Dalai Lama PDFDocument24 pagesOn Emptiness, Dalai Lama PDFRicardo GrácioNo ratings yet

- Henry Corbin Apophatic Theology As Antidote To NihilismDocument30 pagesHenry Corbin Apophatic Theology As Antidote To NihilismMaani GharibNo ratings yet

- Quotes From Taoist Book Chuang TzuDocument39 pagesQuotes From Taoist Book Chuang TzuScott ForsterNo ratings yet

- Female Sufi Leaders in Turkey: Signals of A New Social Pattern Emerging in Seculer SideDocument21 pagesFemale Sufi Leaders in Turkey: Signals of A New Social Pattern Emerging in Seculer SideKishwer NaheedNo ratings yet

- Reconciling Yogas - Haribhadra 039s Collection - of - Views - On - YogaDocument183 pagesReconciling Yogas - Haribhadra 039s Collection - of - Views - On - Yogafredngbs50% (2)

- The Bon Tradition TibetDocument31 pagesThe Bon Tradition TibetDarie Nicolae100% (1)

- Hippe by Paul CoelhoDocument4 pagesHippe by Paul CoelhoLYNDON MENDIOLANo ratings yet

- Daoism: A Short BibliographyDocument42 pagesDaoism: A Short BibliographyBlueLightLionTribe100% (2)

- Weird EncounterDocument9 pagesWeird EncounterDavid Calvert100% (1)

- Reconsideration of Science and - Liu DachunDocument262 pagesReconsideration of Science and - Liu DachunJohnNo ratings yet

- Sŏn Master BeopjeongDocument40 pagesSŏn Master BeopjeongWonjiDharmaNo ratings yet

- Nagarjuna Seventy Verses On Sunyata ShunyatasaptatiDocument27 pagesNagarjuna Seventy Verses On Sunyata ShunyatasaptatiWiranata Surya100% (1)

- When Buddhists Attack The Curious Relationship Between Zen and The Martial ArtsDocument17 pagesWhen Buddhists Attack The Curious Relationship Between Zen and The Martial ArtsDiego IcazaNo ratings yet

- Ethical Principles of Confucianism: Consideration in Ethics April 25, 2013Document37 pagesEthical Principles of Confucianism: Consideration in Ethics April 25, 2013jevon virgioNo ratings yet

- Ingram, The Zen Critique of Pure Lan BuddhismDocument18 pagesIngram, The Zen Critique of Pure Lan BuddhismJaimeGuzmanNo ratings yet

- Practice in The Pure Land TraditionDocument7 pagesPractice in The Pure Land TraditionHaşim LokmanhekimNo ratings yet

- HE USE AND Misuse OF THE Ektashi Name IN Estern ContextDocument76 pagesHE USE AND Misuse OF THE Ektashi Name IN Estern ContextMuhammed Al-ahariNo ratings yet

- The Black Magic in China Known As Ku PDFDocument31 pagesThe Black Magic in China Known As Ku PDFRicardo BaltazarNo ratings yet

- Paul Brunton On MartinusDocument10 pagesPaul Brunton On MartinusludovladeNo ratings yet

- The Hundred Words Stele by Lu Dongbin 4 Commentary by Zhang SanfengDocument2 pagesThe Hundred Words Stele by Lu Dongbin 4 Commentary by Zhang SanfengaaNo ratings yet

- Islam and The Betrayal of TraditionDocument32 pagesIslam and The Betrayal of TraditionMansoor AhmadNo ratings yet

- The Sutra on the Eight Realizations of Great Beings(八大人觉经·中英对照) PDFDocument19 pagesThe Sutra on the Eight Realizations of Great Beings(八大人觉经·中英对照) PDFAnonymous NQfypLNo ratings yet

- My Interview With Steven Harrison About Doing NothingDocument2 pagesMy Interview With Steven Harrison About Doing Nothingapi-3702167100% (1)

- WINKEL Reviews Michel ChodkiewiczDocument4 pagesWINKEL Reviews Michel ChodkiewiczashfaqamarNo ratings yet

- The Sutra of Causes and Effects of ActionsDocument6 pagesThe Sutra of Causes and Effects of ActionsBen Van HamNo ratings yet

- Royal Song of SarahaDocument11 pagesRoyal Song of Sarahaapi-26231809100% (1)

- "The Book of Changes As A Mirror of The Mind: The Evolution of TheDocument19 pages"The Book of Changes As A Mirror of The Mind: The Evolution of Thez. velagicNo ratings yet

- What Is Geyi - V MairDocument31 pagesWhat Is Geyi - V MairbodhitanNo ratings yet

- Review - Cultivating Original Enlightenment - Wonhyo's Exposition of The Vajrasamadhi-Sutra, by Robert EDocument5 pagesReview - Cultivating Original Enlightenment - Wonhyo's Exposition of The Vajrasamadhi-Sutra, by Robert EmoorgiftNo ratings yet

- Liland - The Transmission of The Bodhicaryavatara (2009)Document116 pagesLiland - The Transmission of The Bodhicaryavatara (2009)moorgiftNo ratings yet

- Nagarjunas Letter With Rendawa Commentary Engle TranslationDocument81 pagesNagarjunas Letter With Rendawa Commentary Engle Translationmoorgift100% (2)

- Alberto Todeschini - The Role of Meditation in Asanga's Legitimation of Mahayana PDFDocument37 pagesAlberto Todeschini - The Role of Meditation in Asanga's Legitimation of Mahayana PDFmoorgiftNo ratings yet

- Amida KyoDocument10 pagesAmida KyoHealthTechNo ratings yet

- Rudolf Steiner, The Problem of Jesus and Christ in Earlier TimesDocument24 pagesRudolf Steiner, The Problem of Jesus and Christ in Earlier TimesPiero CammerinesiNo ratings yet

- Douglas Osto - A New Translation of The Sanskrit Bhadracarī With Introduction and Notes PDFDocument21 pagesDouglas Osto - A New Translation of The Sanskrit Bhadracarī With Introduction and Notes PDFmoorgiftNo ratings yet

- Yamada Shoji - The Myth of Zen in The Art of Archery (30p)Document30 pagesYamada Shoji - The Myth of Zen in The Art of Archery (30p)voodoogodsNo ratings yet

- Shankara Manishhaa5Document4 pagesShankara Manishhaa5moorgiftNo ratings yet

- Map of The TaishoDocument36 pagesMap of The Taishoempty2418No ratings yet

- 15 01 14 Sweeping Zen A Pledge From The Next Generation of Zen TeachersDocument7 pages15 01 14 Sweeping Zen A Pledge From The Next Generation of Zen TeachersmoorgiftNo ratings yet

- Record of Dong-Sarn Lerng-GuyDocument66 pagesRecord of Dong-Sarn Lerng-GuymoorgiftNo ratings yet

- Madhyanta VibhangaDocument174 pagesMadhyanta VibhangamoorgiftNo ratings yet

- Foster and Shoemaker: Aitken Life ReplyDocument3 pagesFoster and Shoemaker: Aitken Life ReplymoorgiftNo ratings yet

- MudrasDocument2 pagesMudrasmoorgiftNo ratings yet

- Garma C. C. Chang - The Practice of ZenDocument257 pagesGarma C. C. Chang - The Practice of Zenmoorgift100% (3)

- MahabharataDocument217 pagesMahabharataIndia ForumNo ratings yet

- Vivekachudamani - Adi ShankaraDocument538 pagesVivekachudamani - Adi ShankaraawojniczNo ratings yet

- Sri Ramana As I Knew HimDocument17 pagesSri Ramana As I Knew HimmoorgiftNo ratings yet

- Chrome ThemeDocument1 pageChrome ThememoorgiftNo ratings yet

- Azusa EnglishDocument66 pagesAzusa Englisheltropical100% (1)

- Christian Youth in The Digital AgeDocument3 pagesChristian Youth in The Digital AgeCang OchoaNo ratings yet

- The Sovereign Remedy: Touch-Pieces and The King's Evil. (Pt. I) / Noel WoolfDocument30 pagesThe Sovereign Remedy: Touch-Pieces and The King's Evil. (Pt. I) / Noel WoolfDigital Library Numis (DLN)No ratings yet

- Church Planting Movements IndiaDocument186 pagesChurch Planting Movements IndiaHaindava Keralam100% (3)

- Dragon Red DragonDocument7 pagesDragon Red DragonHANKMAMZERNo ratings yet

- Approved Texts of The Ordinary of The MassDocument7 pagesApproved Texts of The Ordinary of The Massdenzel lanzNo ratings yet

- Maddux Lanny Pat 1973 Brazil PDFDocument12 pagesMaddux Lanny Pat 1973 Brazil PDFthe missions networkNo ratings yet

- Westerholm - Perspectives Old and New On Paul - ReviewDocument6 pagesWesterholm - Perspectives Old and New On Paul - ReviewCătălinBărăscu100% (1)

- Reflections On The World Forum On Liberation and Theology: PORTO ALEGRE, JANUARY 21-25,2005Document3 pagesReflections On The World Forum On Liberation and Theology: PORTO ALEGRE, JANUARY 21-25,2005Oscar CabreraNo ratings yet

- Presentation About ItalyDocument6 pagesPresentation About ItalyArcan Radu AlexandruNo ratings yet

- A Historian Defends U.S Policy of ExpansionDocument2 pagesA Historian Defends U.S Policy of ExpansionHornmaster111No ratings yet

- LANCASTER, Joseph. Improvements in Education 1803Document22 pagesLANCASTER, Joseph. Improvements in Education 1803CarmenNo ratings yet

- ΠΡΟΚΛΟΣDocument20 pagesΠΡΟΚΛΟΣXristina BartzouNo ratings yet

- Skopje: Minube Travel GuideDocument4 pagesSkopje: Minube Travel GuideDelia NechitaNo ratings yet

- AMYR AMIDEN Jse 16 2 KrippnerDocument18 pagesAMYR AMIDEN Jse 16 2 KrippnerRft BrasiliaNo ratings yet

- Black Elk Colonialism and Lakota CatholicismDocument5 pagesBlack Elk Colonialism and Lakota CatholicismkoltritaNo ratings yet

- Separation of Church and State ReportDocument3 pagesSeparation of Church and State ReportDenzhu MarcuNo ratings yet

- Essential Questions - 14Document3 pagesEssential Questions - 14Daniel XuNo ratings yet

- 'Preterism' Another Eschatological View or Heresy?Document4 pages'Preterism' Another Eschatological View or Heresy?mikejeshurun9210No ratings yet

- May EnglezaDocument3 pagesMay EnglezaBiserica Crestina Baptista Speranta Draganesti-OltNo ratings yet

- AntiCALVINism Cultish Side of Calvinism - Micah CoateDocument272 pagesAntiCALVINism Cultish Side of Calvinism - Micah Coateluismendoza1100% (6)

- Talk 1 YctpDocument3 pagesTalk 1 Yctpninya0120No ratings yet

- Litany of Saint Gianna Beretta MollaDocument2 pagesLitany of Saint Gianna Beretta MollaeloquorNo ratings yet

- Pre EGR ExamDocument2 pagesPre EGR ExamJessa AbabaoNo ratings yet

- Augustine and JeromeDocument5 pagesAugustine and Jeromescottkentjones100% (1)

- Monsignor Martin MullerDocument3 pagesMonsignor Martin Mullerapi-26005689No ratings yet

- Essay 2 FinalDocument3 pagesEssay 2 Finalapi-263573673No ratings yet

- Sheffield Mike Patsy 1973 ChileDocument9 pagesSheffield Mike Patsy 1973 Chilethe missions networkNo ratings yet

- DejectionDocument20 pagesDejectionKimi AliNo ratings yet

- The Art of Letters by Lynd, Robert, 1879-1949Document132 pagesThe Art of Letters by Lynd, Robert, 1879-1949Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- No Mud, No Lotus: The Art of Transforming SufferingFrom EverandNo Mud, No Lotus: The Art of Transforming SufferingRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (175)

- My Spiritual Journey: Personal Reflections, Teachings, and TalksFrom EverandMy Spiritual Journey: Personal Reflections, Teachings, and TalksRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (26)

- Summary: How to Be an Adult in Relationships: The Five Keys to Mindful Loving by David Richo: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedFrom EverandSummary: How to Be an Adult in Relationships: The Five Keys to Mindful Loving by David Richo: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (11)

- The Secret of the Golden Flower: A Chinese Book Of LifeFrom EverandThe Secret of the Golden Flower: A Chinese Book Of LifeRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (4)

- Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind: Informal Talks on Zen Meditation and PracticeFrom EverandZen Mind, Beginner's Mind: Informal Talks on Zen Meditation and PracticeRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (73)

- The Psychedelic Experience: A Manual Based on the Tibetan Book of the DeadFrom EverandThe Psychedelic Experience: A Manual Based on the Tibetan Book of the DeadRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (85)

- Buddhism Is Not What You Think: Finding Freedom Beyond BeliefsFrom EverandBuddhism Is Not What You Think: Finding Freedom Beyond BeliefsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (127)

- The Art of Happiness: A Handbook for LivingFrom EverandThe Art of Happiness: A Handbook for LivingRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1206)

- How to Stay Human in a F*cked-Up World: Mindfulness Practices for Real LifeFrom EverandHow to Stay Human in a F*cked-Up World: Mindfulness Practices for Real LifeRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (11)

- The Tibetan Book Of The Dead: The Spiritual Meditation Guide For Liberation And The After-Death Experiences On The Bardo PlaneFrom EverandThe Tibetan Book Of The Dead: The Spiritual Meditation Guide For Liberation And The After-Death Experiences On The Bardo PlaneRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (7)

- Buddha's Brain: The Practical Neuroscience of Happiness, Love & WisdomFrom EverandBuddha's Brain: The Practical Neuroscience of Happiness, Love & WisdomRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (216)

- Don't Just Do Something, Sit There: A Mindfulness Retreat with Sylvia BoorsteinFrom EverandDon't Just Do Something, Sit There: A Mindfulness Retreat with Sylvia BoorsteinRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (28)

- The Gateless Gate: Sacred Writings of Zen BuddhismFrom EverandThe Gateless Gate: Sacred Writings of Zen BuddhismRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (12)

- Buddhism 101: From Karma to the Four Noble Truths, Your Guide to Understanding the Principles of BuddhismFrom EverandBuddhism 101: From Karma to the Four Noble Truths, Your Guide to Understanding the Principles of BuddhismRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (78)

- Think Like a Monk: Train Your Mind for Peace and Purpose Every DayFrom EverandThink Like a Monk: Train Your Mind for Peace and Purpose Every DayRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1027)

- The Tao of Influence: Ancient Wisdom for Modern Leaders and EntrepreneursFrom EverandThe Tao of Influence: Ancient Wisdom for Modern Leaders and EntrepreneursRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (9)

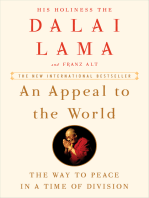

- An Appeal to the World: The Way to Peace in a Time of DivisionFrom EverandAn Appeal to the World: The Way to Peace in a Time of DivisionRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (22)

- The Essence of Self-Realization: The Wisdom of Paramhansa YoganandaFrom EverandThe Essence of Self-Realization: The Wisdom of Paramhansa YoganandaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (43)

- Radical Acceptance: Embracing Your Life with the Heart of a BuddhaFrom EverandRadical Acceptance: Embracing Your Life with the Heart of a BuddhaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (376)

- The Essence of the Bhagavad Gita: Explained by Paramhansa Yogananda as remembered by his disciple, Swami KriyanandaFrom EverandThe Essence of the Bhagavad Gita: Explained by Paramhansa Yogananda as remembered by his disciple, Swami KriyanandaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (40)

- Dancing with Life: Buddhist Insights for Finding Meaning and Joy in the Face of SufferingFrom EverandDancing with Life: Buddhist Insights for Finding Meaning and Joy in the Face of SufferingRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (25)

- Mahamudra: How to Discover Our True NatureFrom EverandMahamudra: How to Discover Our True NatureRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- One Dharma: The Emerging Western BuddhismFrom EverandOne Dharma: The Emerging Western BuddhismRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (28)