Professional Documents

Culture Documents

News Print 2013-05-29 Fed-s-100-Year-r

Uploaded by

gfvilaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

News Print 2013-05-29 Fed-s-100-Year-r

Uploaded by

gfvilaCopyright:

Available Formats

Feds 100-Year Roots Grew From Virginia Congressman - Bloomberg

Page 1 of 6

Feds 100-Year Roots Grew From Virginia Congressman

By Craig Torres - May 29, 2013

As Carter Glass began to sketch out plans for a central bank in 1913, all the U.S. representative from Virginia had to do was read his mail to know he had nationwide support. As soon as money is needed in business in larger amounts than usual, the banks and business men begin to wonder if it is going to be possible to get the funds necessary to see us through, Chas. K. Gleason of Edwin P. Gleason & Son, Converters of Cotton Goods, wrote from Philadelphia on March 26, 1913. Currency Legislation is of utmost importance to business men and all the people connected with them. Gleason was just one of thousands of American bankers, coffee roasters, shoemakers, bed manufacturers, coal jobbers and hardware-store owners who were fed up with the way the financial system was strangling an otherwise booming economy at the turn of the 20th century. The correspondence -- in an archive of Glasss papers at the University of Virginias Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library -- leaves little doubt about why the Federal Reserve Act became a law 100 years ago. The public demanded it. Glass, a 55-year-old Virginia Democrat in 1913, was neither an academic elite nor a man of finance. He was a mostly self-educated journalist who grew up in the aftermath of the Civil War in Lynchburg, a historic transportation and manufacturing hub in the states south-central region. A voracious reader, his speeches show he was a master of the verbal takedown and liked a fight better than a frolic, according to one newspaper headline of the day.

Industrial Revolution

America was caught up in an industrial revolution that its banking system couldnt sustain, as the letter from Gleason emphasizes. Glass and his Senate partner on the bill, Robert Latham Owen Jr. -- a lifelong friend and Oklahoma Democrat who, like Glass, was born in Lynchburg -would watch the banking system trip the economy time and again. Between 1890 and 1914, there were eight recessions lasting an average of 18 months, including banking crises in 1893 and 1907. Shopkeepers, factory owners, farmers and even bankers had identified the U.S. financial system as a matter of national importance.

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/print/2013-05-29/fed-s-100-year-roots-grew-from-v... 29/05/2013

Feds 100-Year Roots Grew From Virginia Congressman - Bloomberg

Page 2 of 6

A letter to Glass from John W. Alling, president of Security Insurance Company in New Haven, Connecticut, shows how the congressman enjoyed immense public support for action.

Most Important

I have been through the panic of 1873, the effects of which lasted for five or six years, and all the ups and downs of periods of financial distress, including the panic of 1907, Alling wrote on April 2, 1913. Currency reform is the most important of any of the proposed reforms now being considered by the American people. Growing up, Glass and Owen, who turned 57 in February 1913, watched the U.S. emerge into the industrial age. Electrification spread with the development of steam turbines, vacuum light bulbs and high-voltage lines. Rail-track miles multiplied, bringing commerce and people to new corners of the country. Ford Motor Co. began mass production of the Model T at its Highland Park, Michigan, plant in October 1913. By the time Owen and Glass were in Congress, Americas strong growth potential was hobbled by a banking system that Glass called a rank panic breeder. From Wall Street to Main Street, people wanted it fixed. Dear Sir: It seems to us our money supply and rates are entirely too irregular and varying, J.L. Hawkins, vice president of Emmons-Hawkins Hardware Co. in Huntington, West Virginia, wrote Glass on March 26, 1913.

1907 Panic

After the 1907 financial crisis sank the country into a 13-month recession, Congress in 1908 authorized a National Monetary Commission. Members of the group delivered a comprehensive report four years later on the state of central banking and financial systems around the world. The U.S., with thousands of single banks, stood in sharp contrast to the sophistication of European countries. If a tobacco farmer in Lynchburg wanted to buy a stove in New York, he or she typically would send the seller a check from a local bank that kept deposits in a correspondent New York bank. The correspondent bank would clear the check, debiting the Lynchburg banks account. Similarly, purchases of tobacco by a New York trader from the Virginia planter might credit the same account. Large New York banks pyramided loans on top of these deposits or even speculated with them.

Gold, Silver

The U.S. currency also was rigid, as national bank and government notes had to be backed -typically by gold, silver or Treasury debt.

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/print/2013-05-29/fed-s-100-year-roots-grew-from-v... 29/05/2013

Feds 100-Year Roots Grew From Virginia Congressman - Bloomberg

Page 3 of 6

In times of panic or higher demand for money and credit, city banks sometimes would refuse to release the country banks clearing deposits or to provide them with cash. To maintain deposits, city banks would raise interest rates when credit was most necessary for the economy during seasonal or emergency demands. Just when we have the greatest prosperity, just when crops are largest and manufacturing most active and money is most needed bankers see surplus funds reduced in consequence of the demand and commence calling in loans, J.M. Lontz, president of F&N Lawn Mower Co. in Richmond, Indiana, wrote Glass on Feb. 28, 1913. It makes prices less for the farmer, wages lower for labor and losses instead of profits for the manufacturer.

Inelastic Money

Money was not, in the language of the day, elastic or responsive to the demands of business or agriculture, nor was it always available where it was needed. At times, the city banks would not honor requests from country banks to withdraw notes, Jeffrey Lacker, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, said in an interview in his office above the James River, which also flows through Lynchburg. The distribution seemed to be up to the big city banks, to the detriment of the country banks. Glass and Owen had a major challenge: They had to craft legislation that paid attention to regional concerns while avoiding the creation of a central bank that would appear as a pawn of the powerful New York banks. The National Monetary Commissions January 1912 report, under the guidance of Rhode Island Republican Senator Nelson Aldrich, called for a National Reserve Association -- in effect a privately controlled entity.

Public Powers

It is a corporation with private stockholders, but it is proposed to make it the principal fiscal agent of the United States and the depository of its funds, the report said. The more important functions of the organization and its principal powers are of a public or semipublic character. Some of the input into the Aldrich Plan came from bankers such as Paul Warburg, a partner at Kuhn, Loeb & Co. and contributor to the commission. He recommended a U.S. central bank in a January 1907 New York Times column and became one of the first Fed board members in August 1914. Warburg, unlike some of his fellow bankers, understood that for a central bank to be politically viable, it had to have popular support and serve regional markets.

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/print/2013-05-29/fed-s-100-year-roots-grew-from-v... 29/05/2013

Feds 100-Year Roots Grew From Virginia Congressman - Bloomberg

Page 4 of 6

Frank Vanderlip, president of National City Bank, Citigroup Inc. (C)s predecessor, also contributed to the Aldrich Plan. He and Warburg joined Aldrich on a secret trip to Jekyll Island, Georgia, in 1910 where they discussed the basic architecture of a U.S. central bank.

Control Controversy

There was not an issue of whether there was going to be something called the Federal Reserve; the issue was who was going to control it, said Allan Meltzer, professor of political economy at Carnegie Mellons Tepper School of Business in Pittsburgh and author of a Fed history. The Democrats were anxious to have it controlled politically. And the bankers were anxious to have it controlled by them. Woodrow Wilson, a Democrat, won the presidency in November 1912 after a Republican Party split; both the House and Senate also were controlled by Democrats. Their election platform included a plank against a centralized central bank, and given the sentiment of the times, the National Monetary Commissions pitch of private bankers working in the public interest was dead on arrival, even though it provided a diagnosis of the problems in the U.S. financial system and descriptions of how reserve-bank systems function. Congressman Arsene Pujo, a Louisiana Democrat who preceded Glass as chairman of the House Committee on Banking and Currency, had just investigated the money trust, pointing to New York banks such as JPMorgan & Co. and National City Bank as agents of concentration.

Cure Evil

The avowed purpose of this bill is to cure this evil; to withdraw the funds of the country from the congested money centers and to make them readily available for business uses in various sections of the country to which they belong, Glass said, describing his bill in 1913. The aversion to New York bankers and centralized control can be seen in a January 1913 letter to Congressman Glass from William Glass of Fresno, California, who wrote that he had worked as a cashier and bookkeeper at a Wall Street brokerage when he was a young fellow in the seventies. Nine-tenths of the money which is up as stakes on such firms bets is borrowed from the capital of the country and should be in use in legitimate commerce or industry, he said. In December 1912, the congressman and his adviser, H. Parker Willis, an editor at the Journal of Commerce, had discussed a decentralized approach with President-elect Wilson. Together, Glass and Wilson worked out a proposal for a system of regional reserve banks that would provide backup currency and credit -- in effect creating a liquid market for the assets held by banks when they needed money.

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/print/2013-05-29/fed-s-100-year-roots-grew-from-v... 29/05/2013

Feds 100-Year Roots Grew From Virginia Congressman - Bloomberg

Page 5 of 6

Political Appointees

Wilson wanted a Federal Reserve Board of political appointees with no balance-sheet or banking powers to oversee the system, essentially checking the power of bankers who sat on regional Fed boards. He also devised a check on the political appointees: Wilson dictated to Glass an outline for a Federal Advisory Council -- a group of 12 bankers appointed from each reserve-bank district that would meet with Fed officials in Washington four times a year to keep them abreast of business and banking. Fed Chairman Ben S. Bernanke and the governors in Washington still meet with the council to this day. The Glass-Willis proposal of December 1912, with Wilsons modifications, formed the basic elements of the Federal Reserve Act signed into law in December 1913, Roger T. Johnson, a former member of the Public Services Department of the Boston Fed, wrote in a study on the historical beginnings of the central bank.

Many-Headed Hydra

It was a complicated, public-private regionalized structure that New York banker Benjamin Strong -- another Jekyll Island participant who later became the first head of the New York Fed -- assailed as a many-headed hydra. Strong and the bankers attacked the legislation while Glass continued to enjoy support from shop owners, manufacturers and at least one Breeder and Feeder of Angus Cattle in Scotland County, Missouri. Dear Sir: Your currency measure before the congress is the most important piece of legislation up before the congress in years, H.H. Schenk wrote Glass on July 29, 1913. What Carter Glass represents is a formulation of a compromise that gets the ball over the finish line of creating an institution that can furnish an elastic currency, but at the same time doing it in a way that respects the diversity of economic and political interests across the country, Lacker said in the interview.

Populist Tension

This whole populist tension between the New York financial center and the rest of the country -- that tension is what really dictated this structure, he added. Hearings on the legislation lasted through the fall in Washington. Without Glasss tenacity, the act might have failed. The Glass proposal was attacked from two sides, Johnson wrote in his history. Bankers (especially from the big city institutions) and conservatives thought that the bill intruded too

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/print/2013-05-29/fed-s-100-year-roots-grew-from-v... 29/05/2013

Feds 100-Year Roots Grew From Virginia Congressman - Bloomberg

Page 6 of 6

much government into the financial structure; while on the other side the agrarians and radicals from the West and South thought that the bill gave the government too little authority over banking. Even among Republicans from agrarian states, there was deep-seated suspicion of a centralized money power. Among Glasss opponents in the House was Charles A. Lindbergh Sr. of Minnesota, the father of the aviator. The Glass bill proposes to incorporate, canonize and sanctify a private monopoly of money, he wrote in his minority report on the bill in 1913.

Gold Pens

The House finally passed the bill on Dec. 22 by a vote of 298 to 60. The following day, the Senate approved the act 43 to 25. On the evening of Dec. 23, Wilson signed the bill with Glass and Owen present. Years later Owen would count a copy of the law on vellum and one of the gold pens Wilson used to sign it among his prized possessions. For his part, Glass continued to defend the Fed during its early years. Speaking in the Senate, where he represented Virginia from 1920 to his death in 1946, he assailed the old system as bank reserve evil and called the rigid currency and lack of flexible reserves the Siamese Twins of disorder. Writing the Federal Reserve Act constituted a challenge to the dominating financial interests of America, he said. In the end, sound economic principles triumphed so completely that many of the great bankers who seemed once implacable now concede that a tremendous advance has been made. To contact the reporter on this story: Craig Torres in Washington at ctorres3@bloomberg.net To contact the editor responsible for this story: Chris Wellisz at cwellisz@bloomberg.net

2013 BLOOMBERG L.P. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/print/2013-05-29/fed-s-100-year-roots-grew-from-v... 29/05/2013

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Allison Weir - A Study of FulviaDocument168 pagesAllison Weir - A Study of Fulviadumezil3729No ratings yet

- Allison Weir - A Study of FulviaDocument168 pagesAllison Weir - A Study of Fulviadumezil3729No ratings yet

- Seldinandal. 2remarksonAcientGreekGeometry TRADocument5 pagesSeldinandal. 2remarksonAcientGreekGeometry TRAgfvilaNo ratings yet

- Jevon sRentTheory Significance White 41 A 7Document15 pagesJevon sRentTheory Significance White 41 A 7gfvilaNo ratings yet

- Liverpool 2008 PDFDocument14 pagesLiverpool 2008 PDFgfvilaNo ratings yet

- Reconciliation MORIDocument29 pagesReconciliation MORIgfvilaNo ratings yet

- Liverpool 2008 PDFDocument14 pagesLiverpool 2008 PDFgfvilaNo ratings yet

- Allison Weir - A Study of FulviaDocument168 pagesAllison Weir - A Study of Fulviadumezil3729No ratings yet

- Incontinentia History Paperv2 8pDocument4 pagesIncontinentia History Paperv2 8pgfvilaNo ratings yet

- Liverpool 2008 PDFDocument14 pagesLiverpool 2008 PDFgfvilaNo ratings yet

- Peirce ApplicabilityofMathematics Zdm985r3Document4 pagesPeirce ApplicabilityofMathematics Zdm985r3gfvilaNo ratings yet

- Review CompnionEncy, OfTheHistoryandPhilosophyofMathematicalScienves KatzDocument8 pagesReview CompnionEncy, OfTheHistoryandPhilosophyofMathematicalScienves KatzgfvilaNo ratings yet

- 67 1 2-VicentofReimsDocument39 pages67 1 2-VicentofReimsgfvilaNo ratings yet

- DefinitionofMathematicalBeauty Blejoviewcontent - CgiDocument16 pagesDefinitionofMathematicalBeauty Blejoviewcontent - CgigfvilaNo ratings yet

- DefinitionofMathematicalBeauty Blejoviewcontent - CgiDocument16 pagesDefinitionofMathematicalBeauty Blejoviewcontent - CgigfvilaNo ratings yet

- DefinitionofMathematicalBeauty Blejoviewcontent - CgiDocument16 pagesDefinitionofMathematicalBeauty Blejoviewcontent - CgigfvilaNo ratings yet

- Aristotle sPriorandBoole sLawsofThoght Corcoran HPL24 (2003) 261 288bDocument28 pagesAristotle sPriorandBoole sLawsofThoght Corcoran HPL24 (2003) 261 288bgfvilaNo ratings yet

- Jevon sRentTheory Significance White 41 A 7Document15 pagesJevon sRentTheory Significance White 41 A 7gfvilaNo ratings yet

- Philip Hardie BkReview PoetisofIllusionDocument2 pagesPhilip Hardie BkReview PoetisofIllusiongfvilaNo ratings yet

- Review 06 (Purola 135-136) Brill Companion-Hellenistic PoetryDocument2 pagesReview 06 (Purola 135-136) Brill Companion-Hellenistic PoetrygfvilaNo ratings yet

- BookReview2008 2008-01-09 Isaeus Edwards UofTexas 2007Document3 pagesBookReview2008 2008-01-09 Isaeus Edwards UofTexas 2007gfvilaNo ratings yet

- Book Review Singing AlexandriaDocument10 pagesBook Review Singing AlexandriagfvilaNo ratings yet

- Aristotle's Protrepticus and Isocrates' AntidosisDocument23 pagesAristotle's Protrepticus and Isocrates' AntidosistiandiweiNo ratings yet

- BookReview2008 2008-01-09 Isaeus Edwards UofTexas 2007Document3 pagesBookReview2008 2008-01-09 Isaeus Edwards UofTexas 2007gfvilaNo ratings yet

- Introduction Isaeus12pnoticeDocument11 pagesIntroduction Isaeus12pnoticegfvilaNo ratings yet

- Review of Bernadete Art of PoeticsDocument2 pagesReview of Bernadete Art of PoeticsgfvilaNo ratings yet

- Deborah Levine Gera, Ancient Greek Ideas On Speech, Language and 0-19-925616-0. $125.00Document4 pagesDeborah Levine Gera, Ancient Greek Ideas On Speech, Language and 0-19-925616-0. $125.00gfvilaNo ratings yet

- Whitehead GONEISDocument30 pagesWhitehead GONEISgfvilaNo ratings yet

- PandoraandtheGoodErisinHesiod Zarecki 631 2571 1 PBDocument25 pagesPandoraandtheGoodErisinHesiod Zarecki 631 2571 1 PBgfvilaNo ratings yet

- PandoraandtheGoodErisinHesiod Zarecki 631 2571 1 PBDocument25 pagesPandoraandtheGoodErisinHesiod Zarecki 631 2571 1 PBgfvilaNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Chapter SummaryDocument4 pagesChapter SummaryIndri FitriatunNo ratings yet

- TurkeyDocument3 pagesTurkeyBảo Hiền Nguyễn VõNo ratings yet

- Sample PDF Economics-12 Exam Handbook For Term-I Exam 2021Document24 pagesSample PDF Economics-12 Exam Handbook For Term-I Exam 2021Disha100% (1)

- Inflation: Its Causes, Effects, and Social Costs: MacroeconomicsDocument61 pagesInflation: Its Causes, Effects, and Social Costs: MacroeconomicsTai612No ratings yet

- Chapter 11Document40 pagesChapter 11raywel100% (3)

- ThesisDocument17 pagesThesisKritiNo ratings yet

- The International Monetary SystemDocument51 pagesThe International Monetary Systemtinashe chavundukatNo ratings yet

- Exercise 3 - SolutionDocument3 pagesExercise 3 - Solution韩思嘉No ratings yet

- Slide CH 5Document39 pagesSlide CH 5KaranNo ratings yet

- Velocity of MoneyDocument1 pageVelocity of MoneyGood Myrmidon100% (1)

- Salvador, Gem D. Prelim Exam FM 7Document3 pagesSalvador, Gem D. Prelim Exam FM 7Gem. SalvadorNo ratings yet

- Inflation Vs Interest RatesDocument12 pagesInflation Vs Interest RatesanshuldceNo ratings yet

- Conditions Home MortgageDocument77 pagesConditions Home MortgageamfipolitisNo ratings yet

- Treasury MAnagement in NepalDocument4 pagesTreasury MAnagement in NepalAntovna GyawaliNo ratings yet

- Inflation Inflation Inflation Inflation: Dr. SK Dr. SK Laroiya Laroiya Dr. SK Dr. SK Laroiya LaroiyaDocument40 pagesInflation Inflation Inflation Inflation: Dr. SK Dr. SK Laroiya Laroiya Dr. SK Dr. SK Laroiya LaroiyaPulkit JainNo ratings yet

- Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland Explains History and Role of Central BanksDocument4 pagesFederal Reserve Bank of Cleveland Explains History and Role of Central BanksCarlos OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Monetary Policy and Theory: A Study of 1724 France 1Document4 pagesRunning Head: Monetary Policy and Theory: A Study of 1724 France 1Jan RunasNo ratings yet

- 106 Powerpoint InflationDocument8 pages106 Powerpoint InflationRingle JobNo ratings yet

- Monetary Policy in IndiaDocument8 pagesMonetary Policy in Indiaamitwaghela50No ratings yet

- FinanceDocument5 pagesFinanceYixuan PENGNo ratings yet

- Tutorial 5 Chapter 4&5Document3 pagesTutorial 5 Chapter 4&5Renee WongNo ratings yet

- Loss Mitigation FlyerDocument2 pagesLoss Mitigation FlyerreomarketingNo ratings yet

- The Different Measures Used For Controlling Inflation Are Shown in Figure-5Document10 pagesThe Different Measures Used For Controlling Inflation Are Shown in Figure-5Abhimanyu SinghNo ratings yet

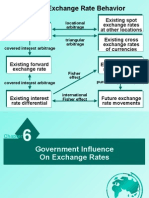

- International Financial Management Chapter 6 - Government Influence On Exchang RateDocument54 pagesInternational Financial Management Chapter 6 - Government Influence On Exchang RateAmelya Husen100% (2)

- GFAL Sample ComputationDocument14 pagesGFAL Sample ComputationIsaac Daplas Rosario100% (2)

- CH 8Document7 pagesCH 8Juan Oliver OndeNo ratings yet

- International Fisher Effect and Exchange Rate ForecastingDocument12 pagesInternational Fisher Effect and Exchange Rate ForecastingRunail harisNo ratings yet

- Reverse Mortgage LoanDocument5 pagesReverse Mortgage Loanjiwrajka.shikharNo ratings yet

- Group Assignment Cover Sheet and Take-home Exercise 1 Refinancing AnalysisDocument4 pagesGroup Assignment Cover Sheet and Take-home Exercise 1 Refinancing AnalysisThi Hong Nhung DauNo ratings yet

- The Cagan Model PDFDocument2 pagesThe Cagan Model PDFMauricioNo ratings yet