Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Allegory

Uploaded by

Izram AliOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Allegory

Uploaded by

Izram AliCopyright:

Available Formats

Allegory

Definition: Allegory is a form of extended metaphor in which objects and persons within a narrative are equated with meanings that lie outside the narrative. Allegory implies two levels of meaning -- the literal (what happens in the narrative) and the symbolic (what the events stand for, outside the narrative). It evokes a dual interest: in the events, characters and setting presented; and in the ideas they represent or the significance they bear. Allegory may involve the personification of abstract qualities (e.g. Pride, Beauty, Death); it can also represent a historical personage (e.g. Gloriana = Queen Elizabeth), a category of individual (e.g. Everyman = all mankind), or another sort of abstraction (Una = the True Church). Characters, events and setting may be historical, fictitious, or fabulous; the key is that they have meanings independent of the action in the surface story. On the surface, Everyman is about a man about to leave on a trip and the people he meets; the Faerie Queene about a knight killing a dragon and rescuing a princess. On the allegorical level, however, both are about the duties of a Christian and the way to achieve salvation. Note that the simple use of personification (e.g. talking animals or teapots) does not constitute allegory in and of itself; in an allegory, characters and objects usually symbolize abstract qualities, and the events recounted convey a coherent message concerning those abstractions. Allegory is frequently, but not always, concerned with matters of great import: life and death; damnation and salvation; social or personal morality and immorality. It can also be used for satiric purposes. In FQ, allegory exists on several levels: religious, historical, mythological. Some characters are named for qualities or actions they represent (Error, Despair); others' names are foreign terms for such qualities (Sans foy = French for "without faith"; Speranza = Italian for "Hope," etc.) Book I contains both religious and historical allegory. Redcrosse Knight is an "Everyman" who represents Holiness or Faith, i.e. how to be a true Christian. Book I is also an allegory of English Church History: in this respect, Redcrosse Knight = St. George, patron saint of England (and so England itself); Una = the "one true faith," Protestantism; Archimago = the pope; Duessa = the duplicitous "false" faith (according to Spenser), Catholicism.

Study Questions:

Read the four-stanza invocation preceding Canto 1 carefully. What is the effect of the allusions to mythological figures (the Muses, Cupid, etc.)? In what literary tradition is Spenser attempting to place his work? What is the significance of the

allusions to Virgil? Note the division of Book I into twelve cantos. Is this structure itself an allusion to a classical model? What is Spenser trying to prove or to achieve? (Recall Sidney's Defense of Poesy.) What is significance of fact that Spenser wrote pastoral poetry in his youth and epic in his maturity? (To whom did he dedicate The Shepherde's Calendar?) Read carefully the letter from Spenser to Sir Walter Raleigh. Note his comments on his purpose in writing the poem; also his remarks concerning other poets (classical and modern) and where he sees himself as fitting into literary tradition. How does he explain choosing King Arthur (back when he was just a Prince) as a focus of his poem? What does he say about Arthur? (Is Arthur in fact a major character in what follows?) What does he say about allegory? In the battle between Redcrosse Knight and Sans Foy (c. 2), what peculiarities do you notice in the descriptions of the battle or of the knights themselves? What do your observations suggest? How do these details shape the allegory? Consider also Redcrosse Knight's two battles with Pride (in the House of Pride; with Orgoglio). Why does he have to fight Pride twice? Is there any difference between the two battles? What is the function of Duessa? Why does she appear when Redcrosse Knight ( = RCK) has been separated from Una? Note the significance of their names (Latin roots: one and two, like unity and duality . . . or duplicity). Why does Duessa lead RCK to the Palace of Pride? Who ultimately overcomes her, and how? What does she represent on the allegorical level(s) of the book? Since The Faerie Queene in some ways resembles an Arthurian romance, Duessa can be compared with the seductresses and sorceresses of Arthurian tradition (Morgan la Fee; Lady Bercilak in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight): she uses a negative form of "courtly love" to manipulate men. If you are unfamiliar with the notion of "Courtly Love," consult theonline reading. Is Spenser comfortable with feminine sexuality? Consider e.g. the references to Duessa's "nether parts"; the false Una in Canto 1 (her seductive speeches are based on courtly love poetry); the chaste and/or maternal women in the House of Holiness; the Faerie Queene Gloriana herself; allusions to Eve. What can you conclude about his attitudes toward women? Redcrosse repeatedly fails to distinguish appearance from reality. Where and when does Spenser play with the appearance-reality motif? Note doublings, pairings of opposites and use of disguises that complicate distinction between appearance and reality. What is their purpose and effect? Compare/contrast several of these parallels (e.g. the House of Pride vs. the House of Holiness; Duessa/"Fidessa" vs. Una; the real and false Redcrosse Knights).

What can you deduce about Spenser's world view (particularly his ideas about religion and politics) based upon your reading of The Faerie Queene? To what extent is Red Cross Knight an "Everyman"?

Canto 1: The Quest

C. 1 st.1-5 [ = canto 1, stanzas 1-5]: Introduction of RCK and Una; first reference to Gloriana, the "Faerie Queene" (RCK grew up at her court -- cf. c. 10 st. 58-66 -which is where Una goes looking for assistance in the form of a brave knight). Damsels in distress coming to court to seek the aid of a knight are typical of Arthurian romance, as well as of the romantic epics of Tasso and Ariosto. Here we also find the first reference to RCK's specific quest: he is to fight a dragon in order to free Una's parents and liberate their kingdom (cf. also c. 7 st. 43-47, c. 11 st.1-3, and all of c. 12). In typical medieval romance (or romantic epic) fashion, the FQ will recount a series of adventures which occur while the hero (RCK) is striving to accomplish his quest. The first of these adventures is RCK's encounter with Error. Note that RCK and Una would not have arrived at Error's cave had they not lost their way (cf. st. 10), and note also what it is that initially leads the couple astray: they get lost while indulging in typical courtly love-type flirtation -- "with pleasure forward led,/ Joying to heare the birdes sweete harmony" (FQ 1.64-65 [ = canto 1, lines 64-5; cf. also st. 10). This negative depiction of courtly love, the seductive power of which tends to distract the hero and lead him astray (even when the object of his affection is as chaste and pure as Una), is related to Spenser's anti-feminism: he seems to distrust women in general and erotic love in particular. Female bodies are invariably associated with sin and corruption, unless the women in question are chaste virgins like Una, Gloriana, or the sisters Fidelia and Speranza in the House of Holiness (or maternal rather than erotic figures, like Dame Caelia's third daughter, Charissa). On the theme of the association of evil with feminine sexuality, note that Duessa -- a lady with very active "nether parts" -- manages to captivate RCK only by (falsely) claiming to be a virgin (c. 2 st. 25); he mistakenly prefers her false appearance of purity over Una's real, but unapparent, innocence. RCK abandons Una because he is convinced of her "wantonness": not only does he think that she has offered to sleep with him -- cf. c. 1 st. 43-55 -- but he believes that she has indulged in lechery with a "lusty squire" after his shocked refusal of her advances (cf. c. 2 st. 3-8). The conventions of "courtly love" will continue to get "bad press" throughout the FQ by their close association with the evil wiles of Duessa (see further discussion under c. 2, below).

It is also interesting to note the sort of path down which the unsuspecting couple, "led with delight" (1.82), stray (st. 10): it is a beaten path that leads to Error's cave (st. 11); compare this well-travelled path with the "broad highway [...] / all bare through people's feet" that leads to the House of Pride (4.17-180; a similar reference is found at 10.86). Contrast both of these well-travelled roads with the rough, difficult, narrow paths leading to, and between structures within, the House of Holiness, c. 10 (look for references to paths in c. 10, st. 5, 10, 33, 35, 51, 55, 61). As noted above, the reference to the "wandering wood" (1.114) recalls the beginning of Dante's Inferno; compare also with the "wearie wandering way" (9.343) which leads the unwary traveller to Despair in c. 9 st. 39 and 43. Another detail to note: what leads RCK into trouble, despite Una's warning, is his PRIDE (first of the Seven Deadly Sins) -- he cannot bear to turn away from an adventure ("shame were to revoke," 1.106), a trait which he shares with many knights from Arthurian romance. The idea of pride being the downfall of the Christian is constantly returned to in the FQ. It is also PRIDE that will lead RCK into his encounter with Despair, despite Trevisan's warnings (c. 9, st. 31-32); cf. also, in addition to the allegorical episode of the House of Pride and the encounter with the giant Orgoglio (Italian for "pride"), the association of the dragon with "outragious [sic] pride" (11.471) immediately before it is slain by RCK at the end of canto 11. Although RCK is successful in his literal battle with Error, note the concrete result of his contact with the monster: he immediately thereafter falls victim to the error of believing Archimago's deceptions. (Una is thus proved right: he should have swallowed his pride and turned away from Error's cave.) He is duped by false visions sent to trouble his sleep by the evil magician Archimago, who appears in the form of a black-clad, rosary carrying Catholic hermit (st. 29-30, 35) who offers the travellers shelter for the night (another motif borrowed from traditional Arthurian romances). Note the classical allusions (Pluto, Gorgon, Morpheus, the river Styx, the doors of Ivory and Silver) in this initial "descent to the Underworld" (st. 37-44; cf. also c.5 st. 31-44). These false visions lead RCK to doubt the chastity (and therefore the goodness) of Una; RCK's error is thus that he is incapable of distinguishing Truth from Falsehood (symbolized in canto 2 by his abandonment of the true Una and taking up with the false Duessa). Archimago's deceptions introduce another important leit-motif in FQ: the idea that appearances are frequently deceptive, and in particular, that things that look particularly splendid or beautiful (i.e. good) often hide great corruption, ugliness and evil. This idea will be discussed more fully in relation to Duessa in canto 2

You might also like

- Discuss Faerie Queene As A Univarsal AllegoryDocument7 pagesDiscuss Faerie Queene As A Univarsal Allegorymahifti94% (17)

- Virtues Actions: The Knight's TaleDocument8 pagesVirtues Actions: The Knight's TaleSilvia FernándezNo ratings yet

- About The Faerie QueeneDocument3 pagesAbout The Faerie QueeneLaurent AlibertNo ratings yet

- 320 Sir Orfeo PaperDocument9 pages320 Sir Orfeo Paperapi-248997586No ratings yet

- "Placed in Firmament": The Dominance of Temperance in Edmund Spenser's The Faerie QueeneDocument25 pages"Placed in Firmament": The Dominance of Temperance in Edmund Spenser's The Faerie Queeneapi-596118571No ratings yet

- Pastoral Poetry and Pastoral ComedyDocument2 pagesPastoral Poetry and Pastoral ComedyrahulhaldankarNo ratings yet

- Odyssey AdventuresDocument4 pagesOdyssey AdventuresmansonismNo ratings yet

- The Dunciad SummaryDocument25 pagesThe Dunciad SummarySAHIN AKHTAR75% (4)

- A Critical History of English LiteratureDocument16 pagesA Critical History of English LiteratureAnacleta TolulaNo ratings yet

- Discourses of Otherness, From Old English Poetry To ShakespeareDocument8 pagesDiscourses of Otherness, From Old English Poetry To Shakespearealetse52No ratings yet

- Allegory - Abrams Extended DefinitionDocument3 pagesAllegory - Abrams Extended DefinitionamyecarterNo ratings yet

- Dante's Dark Wood Cantos 1-2 SummaryDocument3 pagesDante's Dark Wood Cantos 1-2 SummaryHuelequeNo ratings yet

- Draupadi On The Walls of Troy: Iliad 3 From An Indic PerspectiveDocument9 pagesDraupadi On The Walls of Troy: Iliad 3 From An Indic Perspectiveshakri78No ratings yet

- Renaissance Women PaperDocument15 pagesRenaissance Women PapervickaduzerNo ratings yet

- Farie Queen An EpicDocument2 pagesFarie Queen An EpicPapiyaNo ratings yet

- ENG Honours PoetryDocument12 pagesENG Honours PoetryWungreiyon moinao100% (1)

- Tasso's Allegory and Deviations in Jerusalem DeliveredDocument11 pagesTasso's Allegory and Deviations in Jerusalem DeliveredWilliam Joseph CarringtonNo ratings yet

- dramaDocument14 pagesdramaIraNo ratings yet

- Rape of The LockDocument19 pagesRape of The LockTaibur RahamanNo ratings yet

- 90Document4 pages90jgjlllllllfyjfNo ratings yet

- Beowulf Is One More "Paradigmatic Medieval Historical Narrative" (See The Course-Book, Pp. 32-34)Document26 pagesBeowulf Is One More "Paradigmatic Medieval Historical Narrative" (See The Course-Book, Pp. 32-34)Denisa SavaNo ratings yet

- Questions On The TempestDocument3 pagesQuestions On The TempestCamila Franco BatistaNo ratings yet

- Modernist Poetry AssignmentDocument10 pagesModernist Poetry AssignmentKankana DharNo ratings yet

- Short Question of Past Papers 2017 PoetryDocument4 pagesShort Question of Past Papers 2017 PoetryRobina Mudassar100% (1)

- Baptism of Desire Poems Louise ErdrichDocument2 pagesBaptism of Desire Poems Louise ErdrichDevidas Krishnan100% (1)

- Aymer, Hailstorms and FireballsDocument18 pagesAymer, Hailstorms and FireballsValtair Afonso MirandaNo ratings yet

- Twelfth NightDocument20 pagesTwelfth NightDipankar Ghosh100% (1)

- As U Like ItDocument12 pagesAs U Like ItKavita AhujaNo ratings yet

- As You Like It: A Religious AllegoryDocument23 pagesAs You Like It: A Religious AllegoryJOHN HUDSON100% (2)

- A Summary of John DanbyDocument4 pagesA Summary of John Danbynpanagop1No ratings yet

- Jerusalem Delivered: An English Prose VersionFrom EverandJerusalem Delivered: An English Prose VersionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (60)

- Visions of Heaven and Hell in English Li PDFDocument17 pagesVisions of Heaven and Hell in English Li PDFcrystleagleNo ratings yet

- 10 - Chapter 5Document29 pages10 - Chapter 5AnithaNo ratings yet

- Unit-44The Eater Poetry of W.B. YeatDocument12 pagesUnit-44The Eater Poetry of W.B. YeatLima CvrNo ratings yet

- Why Was Greek Mythology Such An Important Theme On Roman SarcophagiDocument4 pagesWhy Was Greek Mythology Such An Important Theme On Roman SarcophagiHaRvArD AlExAnDrOs CrOsSaLoTNo ratings yet

- The Fall of Troy (Barnes & Noble Library of Essential Reading)From EverandThe Fall of Troy (Barnes & Noble Library of Essential Reading)No ratings yet

- Gender Represented in The Gothic Novel: Asmat NabiDocument5 pagesGender Represented in The Gothic Novel: Asmat NabiMegha BlueskyNo ratings yet

- Re 2014 15LectureThreeYeatsDocument7 pagesRe 2014 15LectureThreeYeatsDan TacaNo ratings yet

- Unit-A Study of The Nonnes Preests TaleDocument23 pagesUnit-A Study of The Nonnes Preests TaleNilendra BardiarNo ratings yet

- Notes and Queries. 41.1 (Mar. 1994) : p44+. From Literature Resource CenterDocument5 pagesNotes and Queries. 41.1 (Mar. 1994) : p44+. From Literature Resource CenterBethNo ratings yet

- Heroes and Hells in Beowulf, The Shahnameh, and The Táin Bó CúailngeDocument50 pagesHeroes and Hells in Beowulf, The Shahnameh, and The Táin Bó CúailngeConnell MonetteNo ratings yet

- Up Until Chaucer PDFDocument67 pagesUp Until Chaucer PDFayshaashrafkprNo ratings yet

- Larrington Lokis ChildrenDocument10 pagesLarrington Lokis ChildrenamanitaeNo ratings yet

- 5 Nimmi Jayathurai - Dying FathersDocument14 pages5 Nimmi Jayathurai - Dying Fathersmilll0No ratings yet

- Critical Anthology - MR SmithDocument5 pagesCritical Anthology - MR SmithsimpsonmollyyNo ratings yet

- Marijane Osborn Hleotan and The Purpose of The Old English Rune Poem Vol. 92, No. 2. 1981Document6 pagesMarijane Osborn Hleotan and The Purpose of The Old English Rune Poem Vol. 92, No. 2. 1981Elton O. S. MedeirosNo ratings yet

- Figura Comica de Sócrates en ApuleyoDocument30 pagesFigura Comica de Sócrates en ApuleyoMelina JuradoNo ratings yet

- Paganism and Femininity in Arthurian TalesDocument8 pagesPaganism and Femininity in Arthurian Talesbenjaminspencer080No ratings yet

- As You Like It - ThemesDocument2 pagesAs You Like It - ThemesȘtefan LefterNo ratings yet

- Horace and Shakespeare EssayDocument12 pagesHorace and Shakespeare EssayCatheryne KellyNo ratings yet

- Cormac Mccarthy'S The Road As Apocalyptic Grail Narrative: Lydia CooperDocument20 pagesCormac Mccarthy'S The Road As Apocalyptic Grail Narrative: Lydia CooperelsiebellNo ratings yet

- Joseph Andrews Lecture 1Document7 pagesJoseph Andrews Lecture 1khushnood aliNo ratings yet

- Measure For Measure LuisDocument8 pagesMeasure For Measure LuisSridhar RaparthiNo ratings yet

- Pessimism in Philip Larkin'S Poetry:: "Church Going"Document19 pagesPessimism in Philip Larkin'S Poetry:: "Church Going"Laiba Aarzoo100% (1)

- Characteristics in Renaissance PoemsDocument2 pagesCharacteristics in Renaissance PoemsMelisa Parodi0% (1)

- Reflections of Virgil in MiltonDocument12 pagesReflections of Virgil in MiltonGraecaLatinaNo ratings yet

- Conclusão - The Living As The DeadDocument7 pagesConclusão - The Living As The DeadPaulo MarcioNo ratings yet

- Gods, Ghosts, and Shelley's Atheos' 15p, 2010!Document15 pagesGods, Ghosts, and Shelley's Atheos' 15p, 2010!thanoskafkaNo ratings yet

- Deconstructing Royal Symbolism in MNDDocument5 pagesDeconstructing Royal Symbolism in MNDSagar PatelNo ratings yet

- Microsoft Word Shortcut Keys PDFDocument7 pagesMicrosoft Word Shortcut Keys PDFIzram AliNo ratings yet

- Microsoft Word Shortcut Keys PDFDocument7 pagesMicrosoft Word Shortcut Keys PDFIzram AliNo ratings yet

- Csi 22Document6 pagesCsi 22Izram AliNo ratings yet

- Comic Epic Poem in ProseDocument3 pagesComic Epic Poem in ProseIzram AliNo ratings yet

- Bapsi Sidhwa's novel explores the partition of IndiaDocument8 pagesBapsi Sidhwa's novel explores the partition of IndiaIzram AliNo ratings yet

- Microsoft Word Shortcut Keys PDFDocument7 pagesMicrosoft Word Shortcut Keys PDFIzram AliNo ratings yet

- Canterbury Tales PilgrimsDocument12 pagesCanterbury Tales PilgrimsIzram AliNo ratings yet

- Jane Austen: Emma: Acknowledgement: This Work Has Been Summarized Using The Penguin 1996 EditionDocument3 pagesJane Austen: Emma: Acknowledgement: This Work Has Been Summarized Using The Penguin 1996 EditionIzram AliNo ratings yet

- Types of CriticismDocument2 pagesTypes of CriticismIzram AliNo ratings yet

- Eight Epic Conventions in ParadiseDocument7 pagesEight Epic Conventions in ParadiseIzram AliNo ratings yet

- Gradgrind's Utilitarianism fails in Hard TimesDocument1 pageGradgrind's Utilitarianism fails in Hard TimesIzram AliNo ratings yet

- Canterbury Tales CharactersDocument28 pagesCanterbury Tales CharactersIzram AliNo ratings yet

- Types of CriticismDocument2 pagesTypes of CriticismIzram AliNo ratings yet

- William DalrympleDocument32 pagesWilliam DalrympleIzram AliNo ratings yet

- Words WorthDocument17 pagesWords WorthMichela MaroniNo ratings yet

- Sociolinguistics 3: Classification: Social Groups, Languages and DialectsDocument33 pagesSociolinguistics 3: Classification: Social Groups, Languages and DialectsIzram AliNo ratings yet

- Differences Between Spoken and Written DiscourseDocument19 pagesDifferences Between Spoken and Written DiscourseIzram Ali100% (1)

- Mgt501 Mid Spring 2007 s2Document9 pagesMgt501 Mid Spring 2007 s2Izram AliNo ratings yet

- Tess of The DurbervillesDocument11 pagesTess of The DurbervillesIzram AliNo ratings yet

- SyntaxDocument24 pagesSyntaxIzram AliNo ratings yet

- Characters of Paradise LostDocument2 pagesCharacters of Paradise LostIzram AliNo ratings yet

- Law of Torts - Bhim Singh v. State of Jammu& KashmirDocument16 pagesLaw of Torts - Bhim Singh v. State of Jammu& KashmirAniket Sachan100% (4)

- Faerie Queen As AllegoryDocument2 pagesFaerie Queen As AllegoryMuhammad HammadNo ratings yet

- Leon vs. Manufacturers Life Ins CoDocument6 pagesLeon vs. Manufacturers Life Ins CoAira Mae LayloNo ratings yet

- Romantic Book CollectionDocument5 pagesRomantic Book CollectionNur Rahmah WahyuddinNo ratings yet

- Litany For The Faithful DepartedDocument2 pagesLitany For The Faithful DepartedKiemer Terrence SechicoNo ratings yet

- Angels MedleyDocument7 pagesAngels MedleywgperformersNo ratings yet

- FULE vs. CADocument6 pagesFULE vs. CAlucky javellanaNo ratings yet

- Angelou's "Caged BirdDocument2 pagesAngelou's "Caged BirdRodrigo CanárioNo ratings yet

- 41 IMIDC V NLRCDocument7 pages41 IMIDC V NLRCcarafloresNo ratings yet

- Philippine Presidents Administration EcoDocument32 pagesPhilippine Presidents Administration EcoLucille BallaresNo ratings yet

- Sexual Harassment Prevention in Schools - SafeSchoolsDocument1 pageSexual Harassment Prevention in Schools - SafeSchoolsWan Yoke NengNo ratings yet

- Mock Bar Test 1Document9 pagesMock Bar Test 1Clark Vincent PonlaNo ratings yet

- Sofitel Montreal Hotel and Resorts AgreementDocument3 pagesSofitel Montreal Hotel and Resorts AgreementJoyce ReisNo ratings yet

- Middle East Anti Bribery and Corruption Regulations Legal Guide 2018Document66 pagesMiddle East Anti Bribery and Corruption Regulations Legal Guide 2018kevin jordanNo ratings yet

- North KoreaDocument2 pagesNorth KoreamichaelmnbNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Global GovernanceDocument28 pagesContemporary Global GovernanceMa. Angelika MejiaNo ratings yet

- Ra 442Document14 pagesRa 442Princess Melanie MelendezNo ratings yet

- 6 Department of Finance vs. Dela Cruz, JR., 768 SCRA 73, August 24, 2015Document66 pages6 Department of Finance vs. Dela Cruz, JR., 768 SCRA 73, August 24, 2015Rhinnell RiveraNo ratings yet

- Alice AdventuresDocument3 pagesAlice Adventuresapi-464213250No ratings yet

- Little Truble in DublinDocument9 pagesLittle Truble in Dublinranmnirati57% (7)

- ISLAMIC CODE OF ETHICS: CORE OF ISLAMIC LIFEDocument2 pagesISLAMIC CODE OF ETHICS: CORE OF ISLAMIC LIFEZohaib KhanNo ratings yet

- Ancient History MCQDocument69 pagesAncient History MCQশ্বেতা গঙ্গোপাধ্যায়No ratings yet

- People v. Deniega y EspinosaDocument10 pagesPeople v. Deniega y EspinosaAlex FranciscoNo ratings yet

- Chapter III Workload of A Lawyer V2Document8 pagesChapter III Workload of A Lawyer V2Anonymous DeTLIOzu100% (1)

- Introduction To The IDDRSDocument772 pagesIntroduction To The IDDRSccentroamérica100% (1)

- Lorie Smith v. Aubrey Elenis, Et Al.: Appeal NoticeDocument3 pagesLorie Smith v. Aubrey Elenis, Et Al.: Appeal NoticeMichael_Lee_RobertsNo ratings yet

- 2016 Ballb (B)Document36 pages2016 Ballb (B)Vicky D0% (1)

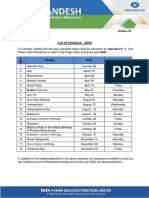

- Holiday List - 2020Document3 pagesHoliday List - 2020nitin369No ratings yet

- Strictly Private & Confidential: Date: - 07-01-18Document4 pagesStrictly Private & Confidential: Date: - 07-01-18shalabh chopraNo ratings yet

- United States v. Samuel Horton, II, 4th Cir. (2012)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Samuel Horton, II, 4th Cir. (2012)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet