Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Pandoc Mode Manual

Uploaded by

norbulinuksCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Pandoc Mode Manual

Uploaded by

norbulinuksCopyright:

Available Formats

Emacs pandoc-mode

Joost Kremers 28 Feb 2012

1 Introduction

pandoc-mode is an Emacs mode for interacting with Pandoc. Pandoc is a program (plus libraries) created by John MacFarlane that can convert a text written in one markup language into another markup language. Supported input formats are markdown and (subsets of) reStructuredText, HTML, and LaTeX. Supported output formats are, among others, markdown, HTML(5), LaTeX, PDF, OpenOffice.org text document (odt), MS Word (docx), GNU Texinfo, MediaWiki markup, groff man pages, and several slide show formats. pandoc-mode is implemented as a minor mode that can be activated alongside the major mode for any of the supported input formats. It provides facilities to set the various options that Pandoc accepts and to run Pandoc on the input file. It is possible to create different output profiles for a single input file, so that you can, for example, write your text in markdown and then translate it to HTML for online reading, PDF for offline reading and Texinfo for reading in Emacs. The current version of pandoc-mode is 2.1.1 and is compatible with Pandoc version 1.9.

2 Installation

Installing pandoc-mode is easy: just put pandoc-mode.el into Emacs loadpath (you can byte-compile it if you wish) and add the following line to : (load "pandoc-mode") This command simply loads pandoc-mode, it obviously does not activate it. In order to activate it in a buffer, you need to type M-x pandoc-mode. If you want to start pandoc-mode automatically when you load e.g., a markdown file, you can add a hook to your : 1

(add-hook 'markdown-mode-hook 'turn-on-pandoc) However, if you do not want to start pandoc-mode every time you work on a markdown document, you can use a different function in markdown-mode-hook: instead of using turn-on-pandoc, you can use conditionally-turn-on-pandoc. This function checks if a default settings file exists for the file youre opening and only turns on pandoc-mode if it finds one. (For more info on the settings file, see the section Settings Files.) Additionally, if you want to automatically load a pandoc-mode settings file for the file youre opening, you can add the following to your : (add-hook 'pandoc-mode-hook 'pandoc-load-default-settings) The function pandoc-load-default-settings checks if a default settings file exists for the file being loaded and reads its settings if it finds one.

3 Usage

When you start pandoc-mode, a menu appears through which all of Pandocs options can be set and through which you can run Pandoc on your current document, or load or save settings files. The most important functions provided by pandoc-mode can also be accessed through the keyboard, but setting options can only be done through the menu (although it is possible to bind your own keys to the functions to set options; see the section Using The Keyboard). The menu is divided into two parts. The upper half contains items related to running Pandoc, the lower half is the part where the various settings can be set and changed.

3.1 Input and output formats

The most important settings are the input and output formats. The input format is set automatically by Emacs on the basis of the major mode, but you can change it through the menu if you need to. The output format defaults to Native Haskell, so most likely you will want to set it to something else before you run Pandoc. Note that the output format can also be set through the keyboard with C-c / w (TAB completion works.) As already stated, you may wish to use different output formats for a single input file. Most likely, the options that you want to pass to Pandoc will be different for each output format. To make this easier, pandoc-mode has the ability to save the settings for a specific output format. If you choose Save File Settings from the menu (C-c / s), Emacs saves the current settings to a hidden file in the same directory as the file youre editing. The name of this file is derived from the input file, appended with the 2

name of the output format and the string .pandoc. (See the section Settings Files for details.) A single document can have a settings file for each output format that Pandoc supports. For example, for this manual, which is written in markdown, I have three settings files, one for HTML output, one for LaTeX output and one for Texinfo output. These can simply be created by setting all options the way you want them for the first output format, save them, then choose another output format, set the required options, save again, etc. Because the name of a settings file contains the output format for which it was created, the different settings files wont interfere with each other. On systems that have symbolic links, it is also possible to specify a default output format. By selecting Set As Default Format from the Pandoc menu, a symbolic link is created to the settings file of the current output format (a settings file is created if one doesnt exist yet). This symbolic link has default as format in its name. The file it points to is read by the function pandoc-load-default-settings, making it possible to automatically load a specific settings file when pandoc-mode is invoked. When you switch output formats, either through the menu or with the keyboard (with C-c / w), Emacs checks if a corresponding settings file exists and loads it if one is found. That is, you can load a different settings file by simply switching output formats. Note that the current output format is always visible in the mode line: the lighter for pandoc-mode in the mode line has the form Pandoc/<format>, where <format> is the current output format.

3.2 Auxiliary files and options

The settings part of the menu contains two more submenus: Files and Options. Under Files, you can set various files that may be used by Pandoc, such as a template file, the reference ODT file, the CSS style sheet, files to be included in the header or before/after the body, etc. Most of these submenus have two options: no file, or specify a file. The Files submenu also contains options for the output file and output directory. These are treated somewhat differently from the other files, see the section Setting an output file for details. When Emacs calls pandoc, it expands filenames, so that they are absolute and dont contain any abbreviations (such as for ones home directory). This means you can have relative filenames in your settings, or indeed , which can be practical if you move settings files to different locations or e.g. between computers with different OSes. (For example, Linux expands to /home/<user>, while on OS X it becomes /Users/<user>.) The CSS style sheet is an exception to this: Emacs always cuts off the directory part of the filename you specify as CSS style sheet and doesnt expand it. The reason for this is that the CSS style sheet will normally be transferred along with the output file(s)

to a server, where it will most likely be in a different directory than on the computer youre generating your .html-files on. Under Options, you can set various other options. Some of these require user input, others can only be toggled on or off. Furthermore, the menu contains an option to get a list of all the settings that you have defined (this function is also available by typing C-c / S). This displays all settings in the *Pandoc output* buffer in the same manner in which they appear in a settings file, i.e., with the following format: <option>::<value>

3.3 Template variables

As of Pandoc v1.4, the custom header files are deprecated and replaced by so-called template files (see the Pandoc documentation for details). When you create a custom template file, you may also specify your own variables. pandoc-mode allows you to set or change template variables through the menu (under the Options submenu) or the keyboard, with C-c / v. Emacs will ask you for the name of a variable and a value for it. If you provide a name that already exists (TAB completion works), the new value replaces the old one. Deleting a template variable is done with the corresponding menu item or by calling C-c / v with the prefix argument C-u - (or M--). Emacs will ask you for the variable name (TAB completion works here, too) and removes it from the list. Template variables are saved in the settings file and can also be viewed with C-c / S. They appear in the following format: variable::<name>:<value>

3.4 Running Pandoc

The first item in the menu is Run Pandoc (also accessible with C-c / r), which, as the name suggests, runs Pandoc on the document, passing all options you have set. By default, Pandoc sends the output to stdout, which is redirected to the buffer *Pandoc output*. (Except when the output format is odt, epub or docx, in which case output is always sent to a file.) The output buffer is not normally shown, but you can make it visible through the menu or by typing C-c / V. Error messages from Pandoc are also displayed in this buffer. Note that when you run Pandoc, Pandoc doesnt read the file on disk, rather, Emacs feeds it the contents of the buffer through stdin. This means that you dont actually have to save your file before running Pandoc. Whatever is in your buffer, saved or not, is passed to Pandoc. If you call this command with a prefix argument (C-u C-c / r), Emacs asks you for an output format to use. If there is a settings file for the format you specify, the 4

settings in it will be passed to Pandoc instead of the settings in the current buffer. If there is no settings file, Pandoc will be called with just the output format and no other options. Note that specifying an output format this way does not change the output format or any of the settings in the buffer, it just changes the output profile used for calling Pandoc. This can be useful if you use different output formats but dont want to keep switching between profiles when creating the different output files.

3.5 Setting an output file

If you want to save the output in a file rather than have it appear in a buffer, you can set the output file through the menu. Note that setting an output file is not the same thing as setting an output format (though normally the output file has a suffix that indicates the format of the file). The Output File submenu has three options: the default is to send output to stdout, in which case it is redirected to the buffer *Pandoc output*. Alternatively, you can let Emacs create an output filename for you. In this case the output file will have the same base name as the input file but with the proper suffix for the output format. Lastly, you can also specify an output file yourself. Note that Pandoc does not allow output to be sent to stdout if the output format is an OpenOffice.org Document (ODT), Epub or MS Word (docx) file. Therefore, Emacs will always create an output filename in those cases, unless of course youve explicitly set an output file yourself. The output file you set is always just the base filename, it does not specify a directory. Which directory the output file is written to depends on the setting Output Directory (which is not actually a Pandoc option). Emacs creates an output destination out of the settings for the output directory and output file. If you dont specify any output directory, the output file will be written to the same directory that the input file is in.

3.6 Creating a pdf

The second item in the menu is Create PDF (C-c / p). This option calls Pandoc with an output file with the extention .pdf, causing Pandoc to create a pdf file by first converting to .tex and then calling LaTeX on it. If you choose this option, Emacs checks if your current output format is latex. If it is, Emacs calls Pandoc with the buffers settings. If the output format is something other than latex, Emacs checks if you have a settings file for LaTeX output and uses those settings. This allows you to create a pdf without having to switch the output format to LaTeX.

If your current output format is not LaTeX and no LaTeX settings file is found, Emacs calls Pandoc with only the input and output formats. All other options are unset. (Note that you can force Emacs to check for a LaTeX settings file by calling C-c / p with a prefix argument.)

4 Projects

If you have more than one file in a single directory for which you want to apply the same Pandoc settings, it is rather cumbersome to create a settings file for each of them, and even more cumbersome if you want to change something in those settings. To deal with such cases, pandoc-mode allows you to create a project file. A project file is called Project.<format>.pandoc and is essentially a normal settings file. The difference is that it defines settings that apply to all files in the directory. In order to distinguish settings from a project file and settings from a file-specific settings file, the former are called project settings and the latter local settings. You can create a project file by selecting Project | Save Project File from the menu (or with the key sequence C-c / P s). Emacs then simply saves the settings of the current file to the project file. This means that all the settings for the current input file become project settings. Just like a local settings file, a project file also contains an output format in its filename. This means that you can have different project files for different output formats. Furthermore, it is also possible to define a default project format: when you set a default format through the menu, Emacs makes both the project file and the local settings file for the current output format the default. If there is no project file for the current output format, however, a default will not be created. (This differs from local settings files: if you set a default output format, Emacs will create a local settings file if none exists). When Emacs loads Pandoc settings for a file, it first looks for and loads the project file for the selected output format, and then reads the files local settings file, if one exists. This means that the local settings may actually override the project settings: if both files contain a value for a specific option, the one in the local settings file overrides the one in the project file. This means that if you open a file and a project settings file is loaded for it, you can make changes to the options and save those to a local settings file (with the menu option Save File Settings or the key sequence C-c / s). If you want to undo all filespecific settings and return to the settings defined in the project file, you can select the menu item Project | Undo File Settings (C-c / P u). This erases the local options, but only for the current session. If you want to make the change permanent, you need to save the local settings file (which will then be empty) or just delete it completely.

5 Managing numbered examples

Pandoc provides a method for creating examples that are numbered sequentially throughout the document (see Numbered example lists in the Pandoc documentation). pandoc-mode makes it easier to manage such lists. First, by going to Example Lists | Insert New Example (C-c / c), you can insert a new example list item with a numeric label: the first example you insert will be numbered (@1), the second (@2), and so on. Before inserting the first example item, Emacs will search the document for any existing definitions and number the new items sequentially, so that the numeric label will always be unique. Pandoc allows you to refer to such labeled example items in the text by writing (@1) and pandoc-mode provides a facility to make this easier. If you select the menu item Example Lists | Select And Insert Example Label (C-c / C : note the capital C) Emacs displays a list of all the (@)-definitions in your document. You can select one with the up or down keys (you can also use j and k or n and p) and then hit return to insert the label into your document. If you change your mind, you can leave the selection buffer with q without inserting anything into your document.

6 Using @@-directives

pandoc-mode includes a facility to make specific, automatic changes to the text before sending it to Pandoc. This is done with so-called @@-directives (double-at directives), which trigger an Elisp function and are then replaced with the output of that function. A @@-directive takes the form @@directive, where directive can be any user-defined string. Before Pandoc is called, Emacs searches the text for these directives and replaces them with the output of the functions they call. So suppose you define (e.g., in ) a function pandoc-current-date: (defun pandoc-current-date (output-format) (format-time-string "%d %b %Y")) Now you can define a directive @@date that calls this function. The effect is that every time you write @@date in your document, it is replaced with the current date. Note that the function that the directive calls must have one argument. which is used to pass the output format to the function (as a string). This way you can have your directives do different things depending on the output format. @@-directives can also take the form @@directive{...}. Here, the text between curly braces is an argument, which is passed to the function that the directive calls as its second argument. Note that there should be no space between the directive and the left brace. If there is, Emacs wont see the argument and will treat it as normal text.

It is possible to define a directive that can take an optional argument. This is simply done by defining the argument that the directives function takes as optional. Suppose you define pandoc-current-date as follows: (defun pandoc-current-date (output-format &optional text) (format "%s%s" (if text (concat text ", ") "") (format-time-string "%d %b %Y"))) This way, you could write @@date to get just the date, and @@date{Cologne} to get Cologne, 28 Feb 2012. Two directives have been predefined: @@lisp and @@include. Both of these take an argument. @@lisp can be used to include Elisp code in the document which is then executed and replaced by the result (which should be a string). For example, another way to put the current date in your document, without defining a special function for it, is to write the following: @@lisp{(format-time-string "%d %b %Y")} Emacs takes the Elisp code between the curly braces, executes it, and replaces the directive with the result of the code. @@include can be used to include another file into the current document (which must of course have the same input format): @@include{copyright.text} This directive reads the file copyright.text and replaces the @@include directive with its contents. Processing @@-directives works everywhere in the document, including in code and code blocks, and also in the %-header block. So by putting the above @@lisp directive in the third line of the %-header block, the meta data for your documents will always show the date on which the file was created by Pandoc. If it should ever happen that you need to write a literal @@lisp in your document, you can simply put a backslash \ before the first @: \@@lisp. Emacs removes the backslash (which is necessary in case the string \@@lisp is contained in a code block) and then continues searching for the next directive. The directives are processed in the order in which they appear in the customization buffer (and hence in the variable pandoc-directives). So in the default case, @@include directives are processed before @@lisp directives, which means that any @@lisp directive in a file included by @@include gets processed, but if a @@lisp directive produces an @@include, it does not get processed. (If this should ever be a problem, you can always create a directive @@include2 and have it processed after @@lisp.) 8

After Emacs has processed a directive and inserted the text it produced in the buffer, processing of directives is resumed from the start of the inserted text. That means that if an @@include directive produces another @@include directive, the newly inserted @@include directive gets processed as well.

6.1 Defining @@-directives

Defining @@-directives yourself is done in two steps. First, you need to define the function that the directive will call. This function must take at least one argument to pass the output format and may take at most one additional argument. It should return a string, which is inserted into the buffer. The second step is to go to the customization buffer with M-x customize-group RET pandoc RET. One of the options there is pandoc-directives. This variable contains a list of directives and the functions that they are linked with. You can add a directive by providing a name (without @@) and the function to call. Note that directive names may only consists of letters (a-z, A-Z) or numbers (0-9). Other characters are not allowed. Directive names are case sensitive, so @@Date is not the same as @@date. Passing more than one argument to an @@-directive is not supported. However, if you really want to, you could use split-string to split the argument of the @@-directive and fake multiple arguments that way. A final note: the function that processes the @@-directives is called pandoc-process-directives and can be called interactively. This may be useful if a directive is not producing the output that you expect. By running pandoc-process-directives interactively, you can see what exactly your directives produce before the resulting text is sent to pandoc. The changes can of course be undone with M-x undo (usually bound to C-/), or do your test in the *scratch* buffer.

6.2 Directive hooks

There is another customizable variable related to @@-directives: pandoc-directives-hook. This is a list of functions that are executed before the directives are processed. These functions are not supposed to change anything in the buffer, they are intended for setting up things that the directive functions might need.

7 Using The Keyboard

Although pandoc-mode can be controlled through the menu, it is possible to bind all functions to keyboard sequences. pandoc-mode uses the prefix C-c /, if you bind any functions to keys, it would be best to use this prefix as well. In order to make your life a little easier if you do decide to bind certain option setting functions to key sequences, all of these have been set up so that they can be used with the prefix key

C-u - (or M--) to unset the relevant option, and with any other prefix key to set the default value (if the option has one, of course). The option setting functions are all called pandoc-set-<option> (with the exception of the option --read, i.e., the input format, which is determined automatically and rarely needs to be set by the user). <option> corresponds to the long name of the relevant Pandoc switch. Functions can be bound in the following manner: (define-key 'pandoc-mode-map "\C-c/o" 'pandoc-set-output) The following table lists the keys defined by default: C-c/r Run pandoc on the document C-c/p Run markdown2pdf on the document C-c/s Save the settings file C-c/Ps Save the project file C-c/Pu Remove file-specific settings C-c/w Set the output format C-c/v Set a template variable C-c/V View the output buffer C-c/S View the current settings C-c/c Insert a new (@)-item C-c/C Select and insert a (@)-label

8 Settings Files

As explained above, there are two types of settings files: project files, which apply to all input files in a single directory, and local settings files, which apply only to single input files. Both types of settings files are specific to a single output format, which is specified in the name. Local settings files are hidden (on Unix-like OSes, anyway) and consist of the name of the input file, plus a string indicating the output format and the suffix .pandoc. Project files are not hidden files and consist of the string Project plus the output format and the suffix .pandoc. The format of a settings file is very straightforward. It contains lines of the form: <option>::<value>

10

<option> is one of Pandocs long options without the two dashes. (For the input and output formats, the forms read and write are used, not the alternative forms from and to. Additionally, the option output-dir is valid.) <value> is a string or, for binary switches, either t or nil, which correspond to on or off, respectively. Lines that do not correspond to this format are simply ignored (and can be used for comments). If for some reason you end up writing your own settings file by hand, make sure all your options have the right form, that is, that they contain no spaces and a double colon.

11

You might also like

- Designing An Electrical Installation - Beginner GuideDocument151 pagesDesigning An Electrical Installation - Beginner GuideFrankie Wildel100% (4)

- OpenSCAD CheatSheetDocument1 pageOpenSCAD CheatSheetnorbulinuksNo ratings yet

- Translating Tenses in Arabic-English and English-Arabic ContextsDocument184 pagesTranslating Tenses in Arabic-English and English-Arabic ContextsMuhammad G. Moheb100% (8)

- SCM NotesDocument29 pagesSCM NotesNisha Pradeepa100% (2)

- Dealing with Windows' Maximum Path Name and File Name Length RestrictionsFrom EverandDealing with Windows' Maximum Path Name and File Name Length RestrictionsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- A320 21 Air Conditioning SystemDocument41 pagesA320 21 Air Conditioning SystemBernard Xavier95% (22)

- DharmaDocument1 pageDharmaapi-19435627No ratings yet

- Banking Finance Agile TestingDocument4 pagesBanking Finance Agile Testinganil1karnatiNo ratings yet

- Arabic CalligraphyDocument22 pagesArabic CalligraphyAVI_ROHINI100% (2)

- Batch Programming Basics Part-1Document34 pagesBatch Programming Basics Part-1Shantanu VishwanadhaNo ratings yet

- Mystical Odes of Ibn al-'ArabiDocument172 pagesMystical Odes of Ibn al-'ArabiFidaa TbiniNo ratings yet

- The Future of The Indian Print Media Ind PDFDocument22 pagesThe Future of The Indian Print Media Ind PDFAdarsh KambojNo ratings yet

- Art of Calligraphy in The Ottoman Empire Long PDFDocument15 pagesArt of Calligraphy in The Ottoman Empire Long PDFOtis ReadyNo ratings yet

- Dau Terminal AnalysisDocument49 pagesDau Terminal AnalysisMila Zulueta100% (2)

- Pandoc ManualDocument91 pagesPandoc ManualTejan KarmaliNo ratings yet

- Pandoc User's GuideDocument50 pagesPandoc User's Guidemiguelhernandez199No ratings yet

- Cheat Sheet Pandoc FinalDocument1 pageCheat Sheet Pandoc FinalJuan Miguel GoicoecheaNo ratings yet

- Example 13Document81 pagesExample 13Carlos HumbertoNo ratings yet

- ManualDocument118 pagesManualJosip CindricNo ratings yet

- Batch File CommandsDocument7 pagesBatch File Commandsi_subhasisNo ratings yet

- Batch File CommandsDocument8 pagesBatch File CommandsFrancisIanNo ratings yet

- PostgreSQL - Documentation - 14 - PG - DumpDocument11 pagesPostgreSQL - Documentation - 14 - PG - DumpRakesh AndrotulaNo ratings yet

- Using Sublime Text As A Script Editor - Unify Community WikiDocument6 pagesUsing Sublime Text As A Script Editor - Unify Community Wikicueva de juegosNo ratings yet

- PhreePlot (026 109)Document84 pagesPhreePlot (026 109)Jeison BlancoNo ratings yet

- JavadocDocument4 pagesJavadocapi-3733692No ratings yet

- (RHSA 124) : Creating, Viewing, and Editing Text FilesDocument53 pages(RHSA 124) : Creating, Viewing, and Editing Text FilesRomeo SincereNo ratings yet

- 1 Using SWI-Prolog: 1.1 Starting Prolog and Loading A ProgramDocument9 pages1 Using SWI-Prolog: 1.1 Starting Prolog and Loading A ProgramjairtbNo ratings yet

- MANUAL TeXstudioDocument66 pagesMANUAL TeXstudiourbano2009No ratings yet

- Versa Calc Manual 4Document25 pagesVersa Calc Manual 4Edgar BenitesNo ratings yet

- Canoco GuideDocument6 pagesCanoco GuideMani KandanNo ratings yet

- File Input and Output: Redirection of ErrorsDocument2 pagesFile Input and Output: Redirection of Errorsmarco rossiNo ratings yet

- Free Fortran CompilersDocument4 pagesFree Fortran CompilersRagerishcire KanaalaqNo ratings yet

- IPP M3 C2 Reading _ Writing FilesDocument48 pagesIPP M3 C2 Reading _ Writing FilesDhavala Shree B JainNo ratings yet

- Okapi Omega TX Bench WorkflowDocument13 pagesOkapi Omega TX Bench WorkflowTheFireRedNo ratings yet

- FastCopy v. 3.30-CharacteristicsDocument18 pagesFastCopy v. 3.30-CharacteristicsSalvatore BonaffinoNo ratings yet

- Quick Start: Output FolderDocument35 pagesQuick Start: Output FolderAlexander UcetaNo ratings yet

- OS Lab - Windows CommandsDocument20 pagesOS Lab - Windows Commandsmarkos100% (1)

- Mainframe SAS® For The 21 Century: Kryn Krautheim, National Center For Health Statistics, Research Triangle Park, NCDocument6 pagesMainframe SAS® For The 21 Century: Kryn Krautheim, National Center For Health Statistics, Research Triangle Park, NCsathya_145No ratings yet

- File Management in CDocument22 pagesFile Management in Cbrinda_desaiNo ratings yet

- TeXstudio - User ManualDocument29 pagesTeXstudio - User ManualMariella MateoNo ratings yet

- Gaus TipsDocument17 pagesGaus TipsIshak Ika KovacNo ratings yet

- PugDocument51 pagesPugAnonymous z2QZEthyHoNo ratings yet

- CUPS-PDF v3Document3 pagesCUPS-PDF v3alvonwaldNo ratings yet

- Input Output Intermediate and Look Up FilesDocument12 pagesInput Output Intermediate and Look Up FilesSreenivas Yadav50% (2)

- USING COMMAND LINE AND MANAGING SOFTWAREDocument35 pagesUSING COMMAND LINE AND MANAGING SOFTWAREAdeefa AnsariNo ratings yet

- PDF To TextDocument2 pagesPDF To TextthicsNo ratings yet

- PdfdetachDocument2 pagesPdfdetachsimoo2010No ratings yet

- ReadmeDocument3 pagesReadmeMiguel ManceboNo ratings yet

- Docx4j - Getting StartedDocument36 pagesDocx4j - Getting StartedZaw ManNo ratings yet

- Cygwin and Moshell Installation WCDMADocument4 pagesCygwin and Moshell Installation WCDMADaniel Hernandez100% (2)

- SPSS Input-Output ModuleDocument140 pagesSPSS Input-Output Modulenofind31No ratings yet

- Create PDF/A Files with LaTeXDocument7 pagesCreate PDF/A Files with LaTeXHossainNo ratings yet

- Go For DevOps (151-200)Document50 pagesGo For DevOps (151-200)Matheus SouzaNo ratings yet

- App PCB Environment v1Document10 pagesApp PCB Environment v1Benyamin Farzaneh AghajarieNo ratings yet

- Notes On Linux Operating System: Written by Jan Mrázek For The MIBO (BCMB) 8270L Course Last Updated: Jan 9, 2007Document4 pagesNotes On Linux Operating System: Written by Jan Mrázek For The MIBO (BCMB) 8270L Course Last Updated: Jan 9, 2007mmmaheshwariNo ratings yet

- PHPExcel User Documentation - Reading Spreadsheet Files PDFDocument19 pagesPHPExcel User Documentation - Reading Spreadsheet Files PDFcokanNo ratings yet

- READMEDocument8 pagesREADMESukarno Wong PatiNo ratings yet

- OW Laying Info Plugin Anual: Now Playing Info ManualDocument6 pagesOW Laying Info Plugin Anual: Now Playing Info ManualJustin ProfitNo ratings yet

- System Administration Books - Red Hat Enterprise Linux 5Document136 pagesSystem Administration Books - Red Hat Enterprise Linux 5Asif AbdullahNo ratings yet

- Managing Node Packages with NPMDocument7 pagesManaging Node Packages with NPMAlbano FuttaNo ratings yet

- Castalia - InstallationDocument4 pagesCastalia - InstallationRim NegraNo ratings yet

- Why Use Disk StorageDocument14 pagesWhy Use Disk StorageJavian CampbellNo ratings yet

- User ManualDocument37 pagesUser Manualokfg2005No ratings yet

- Lab Manual FOR Unix Operating System: Ms. A.K. IngaleDocument31 pagesLab Manual FOR Unix Operating System: Ms. A.K. Ingalepranali suryawanshiNo ratings yet

- Turbo C EnvironmentDocument12 pagesTurbo C EnvironmentRohan SinghNo ratings yet

- User ManualDocument37 pagesUser Manualsafia mohamedNo ratings yet

- Tarjuman Ibn-AlArabi NicholsonDocument13 pagesTarjuman Ibn-AlArabi NicholsonnorbulinuksNo ratings yet

- Women in IslamDocument2 pagesWomen in IslamnorbulinuksNo ratings yet

- (Khaled M. Abou El Fadl, Said Arjomand, Nathan BroDocument59 pages(Khaled M. Abou El Fadl, Said Arjomand, Nathan BroAfthab EllathNo ratings yet

- Boogert Notes Maghribi ScriptDocument14 pagesBoogert Notes Maghribi Scriptfadhel2mezliniNo ratings yet

- EmacsWiki - Twittering ModeDocument17 pagesEmacsWiki - Twittering ModenorbulinuksNo ratings yet

- Gnome Gnumeric SpreadsheetDocument2 pagesGnome Gnumeric SpreadsheetnorbulinuksNo ratings yet

- The Oc Ul) - I - Din L-A H Ibi (D 1283) : Metbod Oc Ompu AtionDocument20 pagesThe Oc Ul) - I - Din L-A H Ibi (D 1283) : Metbod Oc Ompu AtionnorbulinuksNo ratings yet

- Eintr PDFDocument270 pagesEintr PDFEL Rey AzulNo ratings yet

- Bodhi LeafDocument1 pageBodhi Leafapi-19435627No ratings yet

- Cutout GreetingDocument2 pagesCutout GreetingsimionNo ratings yet

- Poster General Eo InfoDocument1 pagePoster General Eo InfonorbulinuksNo ratings yet

- HTML5Document28 pagesHTML5Uday VaswaniNo ratings yet

- A Byte of Python 1 92 Swaroop C HDocument118 pagesA Byte of Python 1 92 Swaroop C HIgor TrakhovNo ratings yet

- Colouring LotusDocument1 pageColouring LotusChakramongoliaNo ratings yet

- Buddhist FlagDocument1 pageBuddhist Flagapi-19435627No ratings yet

- Poster Cool ColoursDocument1 pagePoster Cool ColoursnorbulinuksNo ratings yet

- Poster Nifty NumbersDocument1 pagePoster Nifty NumbersnorbulinuksNo ratings yet

- Python Book 01Document200 pagesPython Book 01Kyle StackNo ratings yet

- Byteofpython 120Document110 pagesByteofpython 120Tu LanhNo ratings yet

- Python TutorialDocument82 pagesPython Tutorialsomchat100% (10)

- Thinking in Tkinter (2005)Document53 pagesThinking in Tkinter (2005)norbulinuksNo ratings yet

- The MIT Course of Esperanto - PronunciationDocument1 pageThe MIT Course of Esperanto - PronunciationnorbulinuksNo ratings yet

- XlopDocument53 pagesXlopnorbulinuksNo ratings yet

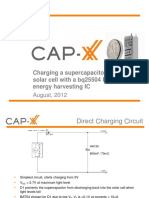

- 1208 CAP XX Charging A Supercapacitor From A Solar Cell PDFDocument12 pages1208 CAP XX Charging A Supercapacitor From A Solar Cell PDFmehralsmenschNo ratings yet

- Seaflo Outdoor - New Pedal Kayak Recommendation July 2022Document8 pagesSeaflo Outdoor - New Pedal Kayak Recommendation July 2022wgcvNo ratings yet

- Philips Lighting Annual ReportDocument158 pagesPhilips Lighting Annual ReportOctavian Andrei NanciuNo ratings yet

- Importance and Behavior of Capital Project Benefits Factors in Practice: Early EvidenceDocument13 pagesImportance and Behavior of Capital Project Benefits Factors in Practice: Early EvidencevimalnandiNo ratings yet

- MONETARY POLICY OBJECTIVES AND APPROACHESDocument2 pagesMONETARY POLICY OBJECTIVES AND APPROACHESMarielle Catiis100% (1)

- Ap22 FRQ World History ModernDocument13 pagesAp22 FRQ World History ModernDylan DanovNo ratings yet

- Alcalel-Lucent WLAN OmniAcces StellarDocument6 pagesAlcalel-Lucent WLAN OmniAcces StellarJBELDNo ratings yet

- Edgevpldt Legazpi - Ee As-Built 121922Document10 pagesEdgevpldt Legazpi - Ee As-Built 121922Debussy PanganibanNo ratings yet

- What is Software Development Life Cycle (SDLC)? Key Phases and ActivitiesDocument11 pagesWhat is Software Development Life Cycle (SDLC)? Key Phases and ActivitiessachinNo ratings yet

- Bridge Ogres Little Fishes2Document18 pagesBridge Ogres Little Fishes2api-246705433No ratings yet

- GIS BasedLandSuitabilityAnalysistoSupportTransit OrientedDevelopmentTODMasterPlanACaseStudyoftheCampusStationofThammasatUniversityandItsSurroundingCommunitiesDocument13 pagesGIS BasedLandSuitabilityAnalysistoSupportTransit OrientedDevelopmentTODMasterPlanACaseStudyoftheCampusStationofThammasatUniversityandItsSurroundingCommunitiesAzka RamadhanNo ratings yet

- Priceliost Ecatalog 2021 Div. DiagnosticDocument2 pagesPriceliost Ecatalog 2021 Div. Diagnosticwawan1010No ratings yet

- Research Paper About Cebu PacificDocument8 pagesResearch Paper About Cebu Pacificwqbdxbvkg100% (1)

- 1st WeekDocument89 pages1st Weekbicky dasNo ratings yet

- Klasifikasi Industri Perusahaan TercatatDocument39 pagesKlasifikasi Industri Perusahaan TercatatFz FuadiNo ratings yet

- Dimetra Tetra System White PaperDocument6 pagesDimetra Tetra System White PapermosaababbasNo ratings yet

- Direct FileActDocument17 pagesDirect FileActTAPAN TALUKDARNo ratings yet

- Javacore 20100918 202221 6164 0003Document44 pagesJavacore 20100918 202221 6164 0003actmon123No ratings yet

- Gray Cast Iron Stress ReliefDocument25 pagesGray Cast Iron Stress ReliefSagarKBLNo ratings yet

- Dhabli - 1axis Tracker PVSYSTDocument5 pagesDhabli - 1axis Tracker PVSYSTLakshmi NarayananNo ratings yet

- Draft SemestralWorK Aircraft2Document7 pagesDraft SemestralWorK Aircraft2Filip SkultetyNo ratings yet

- Patient Safety IngDocument6 pagesPatient Safety IngUlfani DewiNo ratings yet

- March 2017Document11 pagesMarch 2017Anonymous NolO9drW7MNo ratings yet

- ION8650 DatasheetDocument11 pagesION8650 DatasheetAlthaf Axel HiroshiNo ratings yet