Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Supply Chain Risk Management: Case Study

Uploaded by

Bruno GautaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Supply Chain Risk Management: Case Study

Uploaded by

Bruno GautaCopyright:

Available Formats

Case study Supply chain risk management

Peter Finch

Introduction

Do large companies increase their exposure to risk by having small to medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) as partners in business critical positions in the supply chain? This article presents a review of the literature, supplemented by case studies that aims to determine if large companies are taking unnecessary risks related to information systems (IS) management and maintenance of the supply chain.

The author Peter Finch is a Risk Management Consultant with AEA Technology, Warrington, UK. Keywords Supply chain management, Risk management, Small to medium-sized enterprises, Information systems Abstract This article presents a secondary analysis of the literature, supplemented by case studies to determine if large companies increase their exposure to risk by having small- and medium-size enterprises (SMEs) as partners in business critical positions in the supply chain, and to make recommendations concerning best practice. A framework defining the information systems (IS) environment is used to structure the review. The review found that large companies' exposure to risk appeared to be increased by inter-organisational networking. Having SMEs as partners in the supply chain further increased the risk exposure. SMEs increased their own exposure to risk by becoming partners in a supply chain. These findings indicate the importance of undertaking risk assessments and considering the need for business continuity planning when a company is exposed to inter-organisational networking. Electronic access The Emerald Research Register for this journal is available at www.emeraldinsight.com/researchregister The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at www.emeraldinsight.com/1359-8546.htm

Supply Chain Management: An International Journal Volume 9 . Number 2 . 2004 . pp. 183-196 # Emerald Group Publishing Limited . ISSN 1359-8546 DOI 10.1108/13598540410527079

Methods

Secondary analysis of published and grey literature, and case studies was undertaken. The aim of the search strategy was to be comprehensive but not exhaustive. The material was restricted to the English language as there were insufficient resources for translation. The search strategy was as follows. Published and grey literature Electronic searches of the following journal databases were undertaken to identify published literature: ANBAR, BIDS, Emerald, Infotrac, INSPEC, and Ei Compendex. This was supplemented by online searches using the Copernic, Google, and Northern Light search engines: . Electronic searches were undertaken using the terms ``SME'', ``small business'', ``supply chain'', ``risk'', ``risk management'', ``business continuity'', and ``disaster''. Search dates were restricted to between 1995 and 2001. . Additional grey literature (for example, newspaper articles, trade magazines, company policies and procedures) was obtained. . Hand searching was undertaken to identify relevant published and grey literature not identified by electronic searches. Case studies The case studies originate from newspapers, magazine and journal articles, and examples from the author's own practice.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily of his employer.

183

Supply chain risk management

Peter Finch

Supply Chain Management: An International Journal Volume 9 . Number 2 . 2004 . 183-196

In total, in excess of 2,000 articles, papers, surveys and case studies were obtained and screened. Relevant literature was extracted for analysis. Framework Bandyopadhyay et al.'s (1999) IS environment and risk identification framework is used to structure the review. Bandyopadhyay et al. defined the IS environment within a company as comprising three levels: (1) the application level; (2) the organisational level; and (3) the inter-organisational level. The risks affecting each of these environments are outlined in Table I. In the following sections, case studies and evidence from the literature are used as examples of the IS risk types outlined in Bandyopadhyay et al.'s framework, and their impact upon SMEs, large companies and the

supply chain. Where available, examples of best practice are identified.

1 The application level

Natural disasters Whilst these risks affect both large companies and SMEs equally, they may affect SMEs disproportionately hard because of their size and limited resources. Research by the Guardian IT Group (Youett, 2001) into their clients' invocation of business continuity plans found that almost 2 per cent of IS failures in the UK are caused by flood or storm. The following review of the literature looks at the preparedness of a small organisation when faced with flooding and the potential for disruption of the supply chain. Flooding A National Computer Centre (NCC, 1996) survey in 1996 reported that 5 per cent of large

Table I Framework for structuring the review and summary of IS risks IS environment 1. Application level. The risk of technical or implementation failure of an application resulting from either internal or external factors Type of IS risk IS environment and risk identification Examples of IS risks Flooding Human error

2. Organisational level. The risks from the strategic implementation of IS throughout all functional areas

3. Inter-organisational level. The risks associated with inter-organisational networking

Natural disaster flood, storm/lightning strike, disease/epidemic Accidents fires, poorly designed, constructed or maintained systems, buildings, policies and procedures (human error) Deliberate acts (physical actions) sabotage, theft, vandalism, terrorism and hoaxes Data information security risks hackers, viruses, destruction and denial of access Management issues decision making, human resourcing, (succession planning, skill acquisition and retention) As above plus: Legal risk violation of rights, intellectual property Strategic decision making: Competitor's actions Strategic and sustainability risks. Lack of investment to sustain competitive advantage Increased bargaining power suppliers and customers As above plus: weak or ineffective control of suppliers or customers' systems, policies and procedures

Terrorism Information security Skill acquisition and retention Intellectual property/capital Strategic re-organisation

Risk from strategic alliances

Source: Bandyopadhyay et al. (1999)

184

Supply chain risk management

Peter Finch

Supply Chain Management: An International Journal Volume 9 . Number 2 . 2004 . 183-196

companies had experienced flooding. No figures were given for SMEs, however, there is no reason to imagine the figure should differ greatly. The average cost to a large company was found to be 25,540 with a maximum cost of 100,000 (1996 prices). SMEs would probably suffer lower costs should such events occur due to their lower investment in IS. It is likely that the costs would still be considerable when compared to the size of an SME and its available resources. In the UK, floods in late 2000 and early 2001 brought wide-scale disruption. In October, November and December 2000 between one-and-a-half and two times normal rainfall occurred (Environment Agency, 2001). Disruption was widespread with many companies, particularly smaller ones, going out of business or facing an uncertain future (Jolly, 2000). The Federation of Small Businesses gave 20,000 to each of the regions hit by flooding towards the cost of temporary accommodation (Sunday Times, 2000a). In Lewes in East Sussex over 200, mostly small companies were affected by the flooding (Daily Telegraph, 2000a). This led to Sussex Enterprise requesting that the government should draw up contingency plans to help these companies. There are some instances where small companies have exhibited good risk planning and management. One sector badly affected by flooding was the brewing and leisure industry. Pubmaster (a pub operator) estimated that the floods would cost the industry upwards of 100 million in damage and lost revenue with many small firms going out of business (The Independent, 2000). The following case study examines the preparedness of a public house, the King's Arms, when faced with flooding. The King's Arms In York, which suffered extensive flooding of the River Ouse in both 2000 and 2001, many companies suffered long-term damage. The King's Arms public house, which is located on and at times in the River Ouse was not one of them (Rawstorne, 2001). The pub has a ``mobile'' bar and all fixtures and fittings can be removed quickly. Electrical wiring is at ceiling height, the floors flagged and the walls tiled or covered with waterproof plaster. In October 2000 the King's Arms, along with other pubs

and restaurants on the same stretch of river, was flooded. Within 24 hours of the flood water subsiding the pub was able to open. Not all establishments were so prepared or had assessed the risks. The nearby Ship Inn was closed for three months whilst a 250,000 refit was underway (Rutstein, 2000). In this example the brewery may have business continuity procedures in place to ensure its own continuity, however, if a significant number of outlets in the supply chain are unable to continue for an extended period (as was the case in York), then revenues will be harmed. Flooding best practice Whilst this example does not relate specifically to the company's IS infrastructure, the aim is to demonstrate best practice by illustrating the preparedness of the small firm and the potential impact upon the supply chain. It is clear that the impact upon business can be reduced if potential risks are proactively managed, and there is a well-conceived and constructed business continuity plan in place. The following section examines the risks faced by companies from accidents. Accidents These risks can to a large extent be mitigated by a company's policies and procedures. One potential source of accidents common to all sizes of company is human error. Human error A study by Broadcasters Network International (Sullivan, 1999) found that as much as 66 per cent of data loss was caused by human error. The National Computer Centre (NCC, 1996) survey in 1996 reported that 34 per cent of large companies had experienced human error. The average cost to an organisation was 3,570 with a maximum cost of 20,000 (1996 prices). There is no evidence to suggest that the incidence will be greatly different in small companies, however, the average costs may well differ. The following case study examines the effects of human error on two large companies in the supply chain. NASA Mars missions One of the largest and most public examples of human error in recent years was the loss of the North American Space Agency (NASA) Mars

185

Supply chain risk management

Peter Finch

Supply Chain Management: An International Journal Volume 9 . Number 2 . 2004 . 183-196

Climate Orbiter, which disappeared in 1999 at a cost of $250 milllion. NASA had sub-contracted the construction of the Orbiter to Lockheed Martin. An independent review board blamed the loss of the Orbiter on poor project management, a lack of supervision, poor communications and short-sighted engineering. Specifically, the review board found that the root cause of the loss was due to the mission's navigation team being unfamiliar with the spacecraft and lacked training. Notably, the NASA team failed to detect a mistake by Lockheed Martin engineers who delivered navigation information in imperial rather than metric units. The review board concluded that the Climate Orbiter project team did not spend enough time studying what might go wrong during the mission and, consequently, developing contingency procedures to correct mistakes in flight (CNN.com, 1999). Human error best practice The final report from the review board concluded that poor training, inadequate testing, minimal supervision and a lack of people and money meant that there was not enough margin or adequate funding. The result was that risk gradually grew throughout the programme. A thorough and ongoing project risk management process may have identified some of the problems faced by the programme. Whilst this example focuses on large companies, it does highlight the threat posed by human error and how this threat may be amplified by any breakdown in communication between two companies in a supply chain. There is no evidence to suggest that SMEs are any better at communicating with partners than large companies, although case studies of three SMEs by Hill and Stewart (2000) found evidence to suggest internal communications in SMEs are better than larger companies. Deliberate acts (physical actions) These risks are to a limited extent under the control of the company. The NCC (1996) survey found that equipment theft had been experienced by 46 per cent of large companies. The average cost to the organisation was 26,730, with the maximum cost being 750,000. The incidence is likely to be similar for SMEs with the actual cost if not the relative

cost being lower. The case study described below examines another deliberate act that has far-reaching and often unanticipated outcomes: the actions of terrorists. Terrorism Research by the Guardian IT Group reported by Youett (2001) found that almost 2 per cent of IS failures resulted from bombs or terrorist activities. The following case study examines the impact and aftermath of the Manchester (England) bombing in 1996. Manchester bombing The IRA bomb, which exploded in Manchester city centre in 1996 with the equivalent energy of 800kg TNT, injured 216 people and affected over 4,000 companies; 49,000m2 of retail space and 57,000m2 of offices were lost (Jenkins, 1999). Companies in the vicinity of the explosion found that even if there had not been any damage caused by the explosion, they were unable to access premises for at least three days because of a police cordon. Due to the damage caused by the bomb many companies had to relocate away from their original premises. Moyes (1996) reported that five months after the blast many small companies (and in total around 700 companies) had not returned to business. Because of the relocation and the negative publicity surrounding the bombing, those small companies that had returned reported takings were down by 50 per cent (Jeffay, 1996). The total loss in trade was estimated to be 5 million on the first day alone. The Chartered Institute of Loss Adjusters stated that the insured cost of the bomb blast ranged between 25,000 for small units to more than 60 million for one store (Cicutti, 1996). The total cost of claims was estimated to be in the region of 400 million. Substantial proportions of the claims were related to business interruption rather than damage resulting from the bomb explosion itself. Youett (2001) found that it was unlikely that a company's commercial insurance policy covered disaster recovery or extended periods of interruption. This highlights the importance of not only having a business continuity plan, but also of transferring some risk via appropriate types and levels of insurance.

186

Supply chain risk management

Peter Finch

Supply Chain Management: An International Journal Volume 9 . Number 2 . 2004 . 183-196

Terrorism best practice The Home Office (1998) report on the Manchester bomb recommended that those companies without a contingency plan needed to be encouraged to prepare one. Such a plan should include the issues of whether the staff should evacuate the building, and to plan and arrange for the temporary relocation of the business. The report went on to recommend that insurance policies should be reviewed regularly to ensure that they are up to date and cover all potential losses to the business from all possible causes, including disaster recovery and extended periods of disruption. Data/information security risks Data and information security risks are largely under the control of the organisation, although this is not always the case. An Information Security Survey by Ernst & Young (2001) that interviewed 273 chief information officers and IT directors of ``leading companies'' found that over 70 per cent of UK companies had suffered disruption to a critical IT service in the past 12 months and 31 per cent of these disruptions were attributed to failures of or in third party systems, suggesting that many companies are not addressing fully the risks posed by their partners or customers. Those companies that have implemented information security policies or procedures may still be unaware of the risks they face. A study undertaken by ICSA.net (1999) examined 54 corporate Web sites that had implemented security technologies and policies in order to mitigate risk. This study found that of the companies: . 60 per cent were susceptible to denial of service attacks; . 80 per cent did not know what services were on their network and visible over the Internet; . 80 per cent had insufficient security policies; and . 70 per cent of sites with firewalls remained vulnerable to known attacks. This study shows that even in instances where a company has data or information security policies and procedures, unless they have been carefully considered and implemented their utility may be limited.

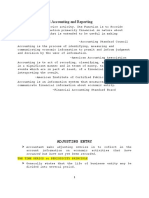

Information security Figure 1 is a graph from the NCC (2000) survey and shows the percentage of companies with an information security policy by size. It is clear from the data that SMEs, and in particular micro and small companies, exhibit less preparedness than larger companies. The following case studies were sourced from the author's practice and examine some aspects of information security and the manner in which SMEs and large companies have approached the risks. Virus detection/hacking A large company had a well-respected virus detection tool on a network server and the virus database was kept up to date. Incoming e-mail messages were automatically scanned for viruses when they were opened. This appeared to be a well-managed situation, however, the e-mail scanner was not set up to monitor the e-mail and Web servers. A hacker was able to place a Trojan (information collecting ``virus'') on the Web server and this went undetected for over a month. The virus scanner should have been integrated with the firewall so that all messages passing across the firewall would be scanned. Firewalls As part of an information security workshop with a large company an employee informed a consultant that their network had a firewall. When this response was probed further it emerged that the client did indeed have a

Figure 1 Percentage of companies with an information security policy

187

Supply chain risk management

Peter Finch

Supply Chain Management: An International Journal Volume 9 . Number 2 . 2004 . 183-196

firewall. Unfortunately the firewall only extended to coverage of one particular e-commerce application. The rest of the company's network (including all e-mail, intranet and Internet servers) was unprotected. An SME had a relatively simple network serving 35 PCs. The company believed that they needed to create an extranet with a firewall to allow remote access to data and e-mail. Having reviewed the options they chose a reputable product, employed a contractor to install it for them, and enjoyed the benefits. What they failed to recognise was that a firewall requires management. The security policies employed must be carefully thought through, and the log files regularly scrutinised for traces of an attack. In this case an intrusion was detected by accident even though there was clear evidence in the firewall log. Backups A large company had an extensive network that was actively managed. Full backups were taken on a routine basis, with incremental backups being taken every night. It was common practice to store backups in a secure location off-site. A junior member of the IS department was tasked with taking the backup tapes to reception every morning. A courier would arrive to collect the latest tapes and return the oldest set. The junior member of staff was offered a job elsewhere. When the staff member left nobody took responsibility for managing the off-site backups. Consequently the courier arrived each day to deposit a box of tapes and take one away. It was over two months before someone noticed that the contents of the boxes never changed. An SME had a digital audio tape (DAT) drive and ``a few tapes'' which they used to back up network servers. The IS manager did not understand the value of the data being stored on the servers, and believed that his equipment was reliable ``because I've not had to change anything for ages''. There were no current system or data backups and there would have been significant business disruption had a problem occurred. User accounts/passwords When working at a large company for an extended period, a consultant was given a user account on the company's network. The basic

access rights did not allow use of one particular folder on a network drive. The consultant telephoned the IS help desk asking for additional access rights. Without further authorisation he was given access to the whole of the network, including personnel and medical records, financial information and minutes of the board meetings. A network manager in a SME created a user account for a consultant, but did not delete the account when the work was completed. Over six months later he went back to the site and was able to log on again. His password had expired but he was allowed to change it as he logged on. Information security best practice Information technology has become essential to the performance and effective running of many companies. As the above examples show, however, many companies, regardless of their size, do not appear to comprehend fully the extent to which their business depend on these systems. In many cases little consideration appeared to be given to the monitoring, control and security of these systems. This was despite the many surveys on the subject and the widespread recognition and publicity they receive. If the monitoring, control and security of these systems are ignored, the consequences can be far reaching with the potential to affect a company severely or even disastrously. The fact that SMEs have been shown to treat information security lightly should be a matter of concern for large companies with whom they may do business. This concern should be even greater if the companies are connected electronically via extranets or electronic data interchange (EDI). Companies should assess and manage the risks arising from the control and security of their own and other companies' systems effectively, allowing these consequences to be mitigated. Management issues Risks arising from management issues, which include decision making, succession planning, skill acquisition and retention can be mitigated to a large extent by organisational policies and procedures. Millward et al. (1992) found that, whereas larger companies rely greatly on formal methods and bureaucratic procedures by

188

Supply chain risk management

Peter Finch

Supply Chain Management: An International Journal Volume 9 . Number 2 . 2004 . 183-196

specialist personnel departments, SME owners/managers are likely to handle recruiting and personnel matters without delegating and are unlikely to have relevant skills. The specific risks to SMEs from shortages of appropriate IS skills and knowledge are examined below and followed by a case study. Skill acquisition and retention According to a survey conducted for the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI, 2000) the perception that a shortage of IS skills is a barrier to the adoption and implementation of IS appears to be higher in medium and large companies. Figure 2 illustrates this perception and also demonstrates a correlation between the perception of a skills shortage, the level of formal IS training and the implementation of IS within companies. The reduced perception of a skills shortage amongst SMEs may be a result of a lower perceived requirement for IS within small companies or a greater degree of confidence in the SMEs' own ability to implement these technologies. A recent survey for the Federation of Small Businesses (2000) found that 53 per cent of small business owners or managers were either satisfied or very satisfied with their ability to implement new technologies. Davies (2000), however, suggests otherwise, reporting that those SMEs who rely on information technology, are increasingly facing an IS skills

Figure 2 UK companies' IT skill shortage and IT training

shortage and that the number of such SMEs is rising rapidly. The following case study examines the skill issues facing a Web-based car sales company. Portfolio For Cars A case highlighted by the Sunday Times (1998), that of ``Portfolio For Cars'', an Internet-based car sales Web media company, highlights the dilemmas encountered by SMEs when facing an IS skills shortage. Portfolio had more than 600 franchised motor dealers using and paying for their services. In the 1997-1978 financial year Portfolio made a profit of almost 250,000 on sales of 1.1 million, from a staff of 63, nine of whom were IS staff. Staff turnover was extremely low and Portfolio had never lost staff to other companies. Due to expansion there was a need to expand the number of IS staff at the rate of one a month. This was proving to be very difficult. A number of reasons were cited for the difficulty in attracting suitable IS staff: . high salary expectations of candidates (30-55,000); . shortage of appropriate Web related skills generally; which was exacerbated by . scarce skills due to geographical location (edge of the Peak District). Portfolio was unwilling to use contract staff for these IS roles. It was also reluctant to train unskilled staff, citing that there were too few people who have the basic skills required. One of the partners in the company laid the blame elsewhere, commenting:

I just don't know if these people exist. Online commerce is the future of retail. Nowhere near enough secondary-school pupils are being trained in digital technologies to make it happen. British business is losing out as a result.

This appears to be a common attitude amongst SMEs. Hill and Stewart (2000) found that in SMEs IS related training and development often does not take place. Where it does it tends to be reactive and informal, aimed at solving short-term problems rather than the development of staff. Small firms tend not to have a lifelong learning culture or see a need for sustained improvement in organisational management (Lawless et al., 2000). 189

Supply chain risk management

Peter Finch

Supply Chain Management: An International Journal Volume 9 . Number 2 . 2004 . 183-196

Skill acquisition and retention best practice For SMEs to want to implement human resource policies, account must be taken of their unique situation. The link between proactive human resource policy and business performance needs to be made clear to SME owners/managers. Alternatively, issues such as a skill shortage may ultimately impact upon partners in the supply chain. Zsidisin et al. (2000) highlighted the risk arising from the capacity constraints of a partner as being one of the major risks affecting supply chains. If human resource management risks are effectively assessed and managed by a company then there is a greater likelihood that suitable remedies can be identified early on.

hardware related development play an important role in innovation. It is necessary for all companies, but especially SMEs, to understand the importance of protecting intellectual property. In particular the possession of intellectual property rights helps an organisation to: . raise finance to develop and market inventions or innovations; . license a product or service to competitors; and . sell or license innovations to larger companies. The following case study examines an SME that has actively protected its intellectual property and looks at the ways in which the company has benefited. Gorix Textiles Gorix is a manufacturer of hi-tech electro-conductive textiles that had sales in 1999 of 270,000 and employed four full- and two part-time staff (Renton, 2000a). Gorix's innovations included materials that regulate the flow of electrical heat according to body temperature, a ``smart'' fire jacket that warns the wearer when their body temperature is too high and, in conjunction with pharmaceutical companies, a heated dressing designed to speed up the healing process. According to the company's two founders, the largest outlay for Gorix has been in legal fees relating to intellectual property. Gorix has spent a total of 280,000 on patents aimed at securing its intellectual property worldwide. This strong defence of intellectual property has meant that Gorix is now in a position to license the manufacture of a number of its products to competitors and larger companies. The proactive approach to this particular legal issue has benefited the company twofold. First, Gorix's ongoing viability has been ensured and, second, it has allowed the company to utilise its intellectual property to competitive advantage. Intellectual property/capital best practice Lang (2001) suggests that the proliferation of software and business method patents and the legal challenges that have become more common have made it necessary for hi-tech companies to scrutinise their legal risks and

2 The organisational level

Legal Organisational policies and procedures can largely mitigate risks such as violation of rights, legal obligations of disclosure and intellectual property issues. Companies listed on the stock exchange (normally larger companies) have to comply with certain legal requirements relating to risk. This is not the case for most small companies. Another legal issue that can impact upon (often hi-tech) SMEs is the handling of intellectual property or capital. Intellectual property/capital According to Roos (1996), the intellectual property or capital of a company includes the knowledge and skills of its employees, the infrastructure, customer relationships, employee motivation, processes that leverage these assets and methods of doing business. A survey by KPMG (Sunday Times, 2000b) found that intellectual property licensing revenues were worth more than $150 billion globally yet this is only 10 per cent of the total intellectual property assets. This suggests that around $1,350 billion of intellectual property assets are currently not realised. The National Criminal Intelligence Service (NCIS, 2000) estimates that in 1998 losses caused by intellectual property theft, in terms of UK sales not made, were 6.42 billion. SMEs' exposure to these losses is not made clear. However, SMEs involved in, for example, software and

190

Supply chain risk management

Peter Finch

Supply Chain Management: An International Journal Volume 9 . Number 2 . 2004 . 183-196

adopt an intellectual property strategy. The above case study of Gorix highlights the importance of this for SMEs, and demonstrates the effectiveness of proactive assessment and management of risks. Strategic decision making Risks such as the actions of competitors and the increased bargaining power of customers and suppliers are external to the company. Formulating an appropriate and effective organisational strategy can to a certain extent mitigate these risks. Strategic re-organisation A recent report undertaken for 3COM (2000) Consulting found that 76 per cent of SMEs in the UK have no IS strategy and did not understand the competitive advantage offered by information technology. The research report concluded that the use of technology by small companies is reactive and complacent, while their budgets are poorly targeted. The following case study examines the strategic capabilities of an SME and its ability to change strategic focus when larger partners' requirements alter. St Bernard Composites The UK aerospace industry is the second largest earning export sector. Companies such as Rolls Royce and BAE Systems buy in about 70 per cent of their production content, much of it from smaller British companies. The aerospace supply chain provides employment for 80,000 people. St Bernard Composites supplies advanced composite components to aero-engine and airframe manufacturers in the aerospace industry. They employ 195 staff and have a turnover of 20 million (Renton, 2000b). Following the publication of a report by AT Kearney and the Society of British Aerospace Companies (SBAC) (AT Kearney and SBAC, 2000) St Bernard reappraised its business strategy. The AT Kearney and SBAC (2000) report found that the global aerospace industry had in the 1990s undergone a radical transformation due to: . large reductions in global defence spending; . erosion of a close privileged relationship with national governments due to

commercial requirements and increases in technology costs; and rapid consolidation of prime contractors in the USA squeezing out smaller European competitors.

Renton (2000b) reported that large aerospace companies aimed to cut the number of suppliers by 80 per cent by utilising techniques first used in the car industry. UK SME suppliers were, therefore, faced with three main challenges to their survival, requiring them to adopt new strategies and new skills: (1) a global redefinition of the existing supply chain; (2) global competition leading to consolidation of major contractors; and (3) customer expectation of self-financed research and development. The major contractors effectively transferred risk and responsibility onto their suppliers. The AT Kearney and SBAC (2000) report concludes by stating that those SMEs who fail to adapt risk being eclipsed by globally oriented competitors. Confronted by these challenges St Bernard began a wholesale rethink of the way they do business. St Bernard is: . actively reducing costs by consolidating in a single location; . investing in new technology; . aggressively targeting export markets; and . diversifying into new markets (using existing techniques and technologies). St Bernard plans to differentiate itself by emphasising quality and continuous improvement. To this end, the company is introducing modern Japanese production techniques and concepts, investigating the possibilities of e-commerce, making strategic alliances and is considering the potential for merger. Strategic re-organisation best practice Whilst the actions of competitors and suppliers external to the company cannot (in most cases) be strictly controlled, formulation and implementation of an appropriate and effective strategy can help a company prepare for many eventualities. In doing so, a company can improve its chances of long-term survival. The St Bernard example suggests that SMEs are at

191

Supply chain risk management

Peter Finch

Supply Chain Management: An International Journal Volume 9 . Number 2 . 2004 . 183-196

just as great a risk from their partners in the supply chain as are large companies. It does, however, illustrate that SMEs are capable of changing the way they work in response to changing circumstances. Whether this case is representative of strategic decision making in SMEs is unclear. The high failure rate amongst SMEs suggests that it may not be.

3 Inter-organisational level

Weak or ineffective control These risks are external to the company and can occur due to uncertainty arising from inter-organisational networking. The aim of this empirical review is to ascertain whether large companies increase their exposure to risk by having SMEs in business critical positions in their supply chain. Das and Teng (1999) suggest such strategic alliances with customers or suppliers are a high-risk strategy because a company has less control over the alliance than it has over its own subsidiaries. The following example examines the extent to which strategic alliances have become commonplace and the potential risks that they can face. Risk from strategic alliances In the UK, the supermarket sector was estimated to be worth around 66 billion in 1997. The largest six food retailers had a 76 per cent share of fruit and vegetable sales with the ``big four'' alone (Tesco, Sainsbury's, Asda and Safeway) accounting for 60 per cent of all grocery sales in the UK (Fearne and Hughes, 1998). These dominant companies have invested heavily in the development of their supply chains to increase efficiency and reduce costs. In order to limit their exposure to risk they have implemented increased monitoring and control of their suppliers. The following case studies examine the risks faced by two companies following the forming of a strategic alliance. Tesco Tesco is the largest and most profitable company in the UK supermarket sector. The results for 2000-2001 show group sales of 22.8 billion with profits before tax at 1.05 billion (Tesco, 2001). Since the 1980s, Tesco has used EDI to order goods from suppliers.

The EDI network connects 1,300 of 2,000 suppliers (around 96 per cent by volume of goods sold) suggesting that many of the other 700 are small suppliers. The EDI network is well suited for the one-way exchange of structured transactions such as purchase orders with suppliers. However, it is not suitable for handling collaborative processes such as the management of promotions. In order to overcome the drawbacks associated with the EDI system (and a target of bringing all of their suppliers online by 2000) Tesco rolled out a Web enabled supply chain (extranet) solution from GE Information Services. Suppliers paid from 100 to 100,000 to join the Tesco Information Exchange (TIE the acronym is intentional), dependent on their size. At the time of writing 600 suppliers (approximately 65 per cent of Tesco business) were using the system. This allowed Tesco and its suppliers to jointly plan, execute, track and evaluate promotions by sharing common data as well as viewing daily electronic point-of-sale data from Tesco stores. Tesco hoped to achieve at least a 20 per cent reduction in stocks as well as increasing the number of products handled only once in the store by 30 per cent (Nairn, 2000). St Ivel St Ivel is a business unit of the Uniq (formerly Unigate) Group and employs over 1,450 staff at five production plants throughout the UK. A total of 70 per cent of production is branded and 30 per cent private label. St Ivel supplies many of the UK supermarkets including Tesco. According to a narrative article by Nairn (2000), TIE has saved St Ivel 30 per cent of annual promotional on-costs. Tesco has, however, experienced difficulties in persuading all of its suppliers to utilise the system fully. Only two of their suppliers have changed fundamentally the way they work as a result of TIE, allowing them to bring products to market much faster than their competitors. A risk in implementing such supply chain management systems, that are designed to tie suppliers to customers and vice versa, is the weakened level of control over supplies. This was exhibited clearly during the weeklong UK fuel crisis of September 2000. Biederman (2000) opined that:

192

Supply chain risk management

Peter Finch

Supply Chain Management: An International Journal Volume 9 . Number 2 . 2004 . 183-196

The crisis revealed that modern day supply chains as finely tuned machines, are highly vulnerable, proving the old adage that a chain is only as strong as the weakest link.

Food and other deliveries to the supermarket chains including Tesco remained largely undisturbed due to the short length of the disruption. This would have been rather different had the crisis gone on any longer (Biederman, 2000). The supermarket's petrol stations were, however, severely disrupted and rapidly ran dry. This had a knock-on effect, as customers were unable to reach many supermarkets. The situation was sufficiently serious to worry investors, with Tesco shares falling by 4.75p (Parkinson, 2000) and analysts forecasting a 200 million reduction in retail sales in that one week alone (Daily Telegraph, 2000b). Risk from strategic alliances best practice The weak control over suppliers and customers in the supply chain can be compounded by the risks highlighted, which affect links up or down the supply chain. Zsidisin et al. (2000) report that whilst proffering many companies a competitive advantage in the marketplace, outsourcing has resulted in corresponding increases in the level of corporate exposure to uncertain events with suppliers. A company should actively assess the risks and threats, not only to itself but also to its direct and indirect suppliers and customers.

Discussion

The aim of this review was to determine if large companies increase their exposure to risk by having SMEs as partners in business critical positions in the supply chain and make recommendations concerning best practice. A number of issues that could potentially impact on the rigour of the process arose that warrant further discussion. The strength of using case studies is that they showed clearly that SMEs can assess and manage risk. However, there was strong evidence in the wider literature to suggest that many SMEs do not assess and manage risk adequately. The case studies originated from a wide variety of sources. This made it difficult to

compare like with like due to the diversity of the sources. Many of the original case studies had different aims to those of this empirical review. Relevant information may have been accessible if appropriate questions had been asked. In certain case studies information was incomplete or absent. In order to address this weakness, supplementary searching of the literature was undertaken to increase the validity of the case studies and the rigour of the research process. Utilising predominantly secondary data for this empirical review allowed a broader selection of case studies to be identified. The case studies, however, did not in all cases examine risks affecting IS. This made it more difficult to generalise about the findings. The literature search revealed fewer IS risk case studies than would have been desirable. This lack of IS risk case studies impacts on the generalisability of the findings. This can be attributed in part to the difficulty of finding information regarding IS and IS risk management in SMEs. It would be useful to conduct a small number of case studies using primary research to verify the findings of this secondary analysis. In addition, whilst identifying some incidences of best IS risk management practice, this review did not identify fully what constitutes best IS risk management practice. This may be due to a reporting bias in the literature that leans toward an examination of poor practice rather than best practice. A carefully constructed primary study designed to ascertain examples of best and poor practice needs to be undertaken to increase the rigour of this empirical review. Table II summarises the areas where best practice was identified in each case study. A common theme identified from the case studies was that whilst there were few specific examples of best practice, there were valuable lessons to be learned from the way individual companies assessed and managed the risks confronting them and planned for the continuation of business should the worst happen. The management of risk is, or should be, a core issue in the planning and management of any organisation. Bandyopadhyay et al. (1999) in their review of the literature stated that four

193

Supply chain risk management

Peter Finch

Supply Chain Management: An International Journal Volume 9 . Number 2 . 2004 . 183-196

Table II IS risks, impact on the supply chain and best practice Examples of IS risks Flooding Human error Terrorism Examples of best practice The impact upon business can be reduced if potential risks are proactively managed, and there is a well-conceived and constructed business continuity plan in place A thorough and ongoing project risk management process may have identified some of the problems faced by the programme Those companies without a contingency plan need to be encouraged to prepare one to include the issues of whether the staff should evacuate buildings, and to plan and arrange for the temporary relocation of the business. Insurance policies should be reviewed regularly to ensure that they are up to date and cover all potential losses to the business from all possible causes If the monitoring, control and security of these systems is ignored, the consequences can be far reaching with the potential to affect a company severely or even disastrously. Companies should assess and manage the risks arising from the control and security of their own and other companies' systems effectively, allowing these consequences to be mitigated The link between proactive human resource management policy and business performance needs to be made clear to SME owners/managers. Alternatively, issues such as a skill shortage may ultimately impact upon partners in the supply chain. If such human resource management risks are effectively assessed and managed by a company then there is a greater likelihood that suitable remedies can be identified early on The proliferation of software and business method patents and the legal challenges that have become more common have made it necessary for hi-tech companies to scrutinise their legal risks and adopt an intellectual property strategy. The case study of Gorix highlights the importance of this for SMEs, and demonstrates the effectiveness of proactive assessment and management of risks Whilst the actions of competitors and suppliers external to the company cannot (in most cases) be strictly controlled, formulation and implementation of an appropriate and effective strategy can help a company prepare for many eventualities. In doing so, a company can improve its chances of long-term survival. The St Bernard example suggests that SMEs are at just as great a risk from their partners in the supply chain as are large companies The weak control over suppliers and customers in the supply chain can be compounded by the risks highlighted, which affect links up or down the supply chain. Zsidisin et al. (2000) report that whilst proffering many companies a competitive advantage in the marketplace, outsourcing has resulted in corresponding increases in the level of corporate exposure to uncertain events with suppliers. A company should actively assess the risks and threats, not only to itself but also to its direct and indirect suppliers and customers

Information security

Skill acquisition and retention

Intellectual property/capital

Strategic re-organisation

Risk from strategic alliances

major components of risk management had been identified: (1) Risk identification identifying and quantifying the exposures that threaten a company's assets and profitability. (2) Risk analysis identifying and assessing the risks to which the company and its assets are exposed in order to select appropriate and justifiable safeguards. (3) Risk reduction, transfer and acceptance reducing or shifting the financial burden of loss so that, in the event of a catastrophe, a company can continue to function without severe hardship to its financial stability. (4) Risk monitoring continually assessing existing and potential exposure. A company manages risk in order to protect its assets and profits, and stay in business.

However, no matter how well risk is managed it is necessary to prepare for negative events. It is important to understand the distinction between risk management and planning for continued operation once a potential risk has occurred (business continuity planning). The management of risks and business continuity planning were two high-level examples identified from the case studies where best practice was demonstrated and positive outcomes were achieved.

Conclusion

The review found that large companies' exposure to risk appeared to be increased by inter-organisational networking. Having SMEs as partners in the supply chain further increased

194

Supply chain risk management

Peter Finch

Supply Chain Management: An International Journal Volume 9 . Number 2 . 2004 . 183-196

the risk exposure. SMEs increased their own exposure to risk by becoming partners in a supply chain and few had made an assessment of the risks involved or had a strategy in place for managing risk. These findings indicate the importance of undertaking risk assessments and considering the need for business continuity planning when a company is exposed to inter-organisational networking.

References

3COM (2000), ``Research from 3Com reveals that over 75 per cent of SMEs currently have no IT strategy in place'', 13 November, available at: www.3com.co.uk/ news/prel_20001113_1.html AT Kearney and SBAC (2000), ``The impact of global aerospace consolidation on UK suppliers'', available at: www.atkearney.com/pdf/eng/aero_consolidation. pdf Bandyopadhyay, K., Mykytyn, P. and Mykytyn, K. (1999), ``A framework for integrated risk management in information technology'', Management Decision, Vol. 37 No. 5, pp. 437-44. Biederman, D. (2000), ``The weak link'', Traffic World, 16 October, available at: www.findarticles.com/cf_0/ m0VOO/3_264/66277581/print.jhtml Cicutti, N. (1996), ``Premiums to rise after IRA bomb costs 400m'', The Independent, 13 July, p. 20. CNN.com (1999), ``NASA: human error caused loss of Mars orbiter'', 10 November, available at: www.cnn.com/ TECH/space/9911/10/orbiter.02/ Daily Telegraph (2000a), ``Businesses may never recover from the floods'', Daily Telegraph, 4 December, available at: http://web4.infotrac.galegroup.com Daily Telegraph (2000b), ``High street suffered in fuel crisis'', Daily Telegraph, 23 September, available at: http:// web4.infotrac.galegroup.com Das, T.K. and Teng, B.-S. (1999), ``Managing risks in strategic alliances'', The Academy of Management Executive, Vol. 13 No. 4, November, p. 50. Davies, L. (2000), ``This time its personnel'', The Guardian, 30 November, available at: www.guardianunlimited. co.uk/Print/0,3858,4098219,00.html Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) (2000), ``Small and medium enterprise (SME) statistics for the UK, 1999'', Statistical News Release, DTI, 7 August, available at: www.dti.gov.uk/ Environment Agency (2001), available at: www.environment-agency.gov.uk/ Ernst & Young (2001), Information Security Survey 2001, Ernst & Young, available at: www.ey.com Fearne, A. and Hughes, D. (1998), ``Success factors in the fresh produce supply chain: some examples from the UK'', executive summary, Wye College, London.

Federation of Small Businesses (2000), ``Barriers to survival and growth in UK small firms'', available at: www.fsb.org.uk Hill, R. and Stewart, J. (2000), ``Human resource development in small organizations'', Journal of European Industrial Training, Vol. 24 No. 2-3-4, pp. 105-17. Home Office (1998), ``Business as usual: maximising business resilience to terrorist bombings'', available at: www.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/horspubs1.html ICSA.net (1999), Information Security: A Practical Solution for Senior Management, available at: www.icsa.net (The) Independent (2000), ``Floods may cost pub industry 100m'', The Independent, 8 November, p. 20. Jeffay, J. (1996), ``Come and find us'', Manchester Metro News, 15 November, p. 1. Jenkins, R. (1999), ``Manchester rises from the rubble'', The Times, 25 November, p. 19. Jolly, I. (2000), ``Murky future for flood hit firms'', 2 November, available at: http://news.bbc.co.uk/hi/ english/business/newsid_998000/998734.stm Lang, J.C. (2001), ``Management of intellectual property rights: strategic patenting'', Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 2 No. 1, pp. 8-26. Lawless, N., Allan, J. and O'Dwyer, M. (2000), ``Face-to-face or distance training: motivating SMEs to learn'', Education + Training, Vol. 42 No. 4-5, pp. 308-16. Millward, N., Stevens, M., Smart, D. and Hawes, W.R. (1992), Workplace Industrial Eelations in Transition: the ED/ESRC/PSI/ACAS Surveys, Dartmouth, Aldershot. Moyes, J. (1996) "Bombed, battered, unbowed, Manchester gets back to business as usual'', The Independent, 2 November, available at: www.rebuildingmanchester.co.uk/articles/art27.htm Nairn, G. (2000), ``IT in retailing: retailer's suppliers can monitor product demand'', 3 May, available at: www.ft.com/ftsurveys/spaad6.htm National Computing Centre (NCC) (1996), ``How real is the threat?'', NCC, available at: www.ncc.co.uk National Computing Centre (NCC) (2000), ``The business information security survey'', NCC, available at: www.ncc.co.uk National Criminal Intelligence Service (NCIS) (2000), ``2000 UK threat assessment'', NCIS, available at: www.ncis. org.uk Rawstorne, T. (2001), ``Still more to come: the Met men warn things will only get wetter this weekend'', Daily Mail, 9 February, p. 9. Renton, J. (2000a), ``Textile makers must cut their cloth to suit the 21st century'', Sunday Times, 7 July, available at: www.enterprisenetwork.co.uk/ knowledge_store/ Renton, J. (2000b), ``Small suppliers must adapt to survive in aerospace shake-out'', Sunday Times, 27 August, available at: www.enterprisenetwork.co.uk/ knowledge_store/ Roos, J. (1996), ``Intellectual capital: what you can measure you can manage'', Perspectives for Manager, IMD, No. 10, November.

195

Supply chain risk management

Peter Finch

Supply Chain Management: An International Journal Volume 9 . Number 2 . 2004 . 183-196

Rutstein, D. (2000), ``Narrow escape from floodwaters'', available at: www.thisisyork.co.uk/york/news/Floods/ news30.html Sullivan, S. (1999), ``Human error: bigger problem than disasters'', ENT, Vol. 4 No. 9, May, p. 3. Sunday Times (1998), ``Skills gap threatens nice little earner'', Sunday Times, 22 November, available at: www.enterprise network.co.uk/knowledge_store/ casestudy_detail. asp?d_id=4 Sunday Times (2000a), ``Grants for flooding'', Sunday Times, 19 November, p. 20. Sunday Times (2000b), ``Intellectual property'', Sunday Times, 1 August, available at: www.enterprise network.co.uk/knowledge_store/ Tesco (2001), ``Tesco preliminary statement of results 52 weeks'', 10 April, available at: www.tesco.com/ talkingTesco/corporateinfo.htm Youett, C. (2001), ``Don't dig yourself into a hole'', IBM Today, February, pp. 47-9.

Zsidisin, G.A., Panelli, A. and Upton, R. (2000), ``Purchasing organization involvement in risk assessments'', Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, Vol. 5 No. 4, pp. 187-97.

Further reading

AT Kearney (2000), ``Strategic information technology and the CEO agenda'', available at: www.atkearney.com Blackburn, R. and Athayde, R. (2000), ``Making the connection: the effectiveness of Internet training in small businesses'', Education + Training, Vol. 42 No. 4-5, pp. 289-98. Parkinson, G. (2000), ``Fuel crisis takes its toll across the board'', Daily Telegraph, 13 September, available at: www.telegraph.co.uk/et?ac= 005236261357609& rtmo=V15xP1wx&atmo=99999999&pg=/et/00/9/13/ cxmktrep.html

196

You might also like

- Exit Procedure FeedbackDocument12 pagesExit Procedure Feedbackraviawasthi100% (1)

- Managing Cybersecurity Risk: Cases Studies and SolutionsFrom EverandManaging Cybersecurity Risk: Cases Studies and SolutionsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Supply Chain Risk ManagementDocument10 pagesSupply Chain Risk Managementultrasonic81No ratings yet

- Deloitte - ERM (Energy Risk Management) For The Energy IndustryDocument16 pagesDeloitte - ERM (Energy Risk Management) For The Energy IndustrylifeinthemixNo ratings yet

- Top 10 Global Supply Chain RisksDocument8 pagesTop 10 Global Supply Chain RisksGabriely MligulaNo ratings yet

- Material Six Steps To Secure Global Supply ChainsDocument23 pagesMaterial Six Steps To Secure Global Supply ChainsborisbarborisNo ratings yet

- Supply Chain Energy Efficiency Unlocks SavingsDocument18 pagesSupply Chain Energy Efficiency Unlocks SavingscesacevNo ratings yet

- Supply Chain Risk Management: Resilience and Business ContinuityDocument27 pagesSupply Chain Risk Management: Resilience and Business ContinuityHope VillonNo ratings yet

- Cyber Crime and Security Survey Report 2012Document40 pagesCyber Crime and Security Survey Report 2012Menelaos ZouzoulasNo ratings yet

- Behavioural Safety and Major Accident Hazards Magic Bullet or Shot in The DarkDocument8 pagesBehavioural Safety and Major Accident Hazards Magic Bullet or Shot in The DarkmashanghNo ratings yet

- Managing Disruption Risks in Supply Chain MGTDocument17 pagesManaging Disruption Risks in Supply Chain MGTpriyal.singh100% (2)

- Sources of Supply Chain Disruptions, PDFDocument38 pagesSources of Supply Chain Disruptions, PDFUmang SoniNo ratings yet

- Resilient Supply Chain - Mansucript-IJPMDocument22 pagesResilient Supply Chain - Mansucript-IJPMUmang SoniNo ratings yet

- Questionnaire On Employee MotivationDocument2 pagesQuestionnaire On Employee MotivationSmiti Walia86% (36)

- Climate Risk & Financial Institutions: Challenges & OpportunitiesDocument136 pagesClimate Risk & Financial Institutions: Challenges & OpportunitiesInternational Finance Corporation (IFC)No ratings yet

- Chevening ScholarshipsDocument15 pagesChevening ScholarshipsWika Atro AuriyaniNo ratings yet

- It Risks in Manufacturing Industry - Risk Management ReportDocument13 pagesIt Risks in Manufacturing Industry - Risk Management Reportaqibazizkhan100% (1)

- Digitalization As Means To Overcome Supply Chain DisruptionsDocument11 pagesDigitalization As Means To Overcome Supply Chain DisruptionsYogi PratamaNo ratings yet

- BMM3113 Academic Skills and Studying With ConfidenceDocument9 pagesBMM3113 Academic Skills and Studying With ConfidenceMD KURBAN SHEIKHNo ratings yet

- Ericsson's Proactive Supply Chain Risk Management Approach After A Serious Sub-Supplier Accident PDFDocument23 pagesEricsson's Proactive Supply Chain Risk Management Approach After A Serious Sub-Supplier Accident PDFcliu0513No ratings yet

- Ericsson's Proactive Supply ChainDocument37 pagesEricsson's Proactive Supply ChainGodwin RichmondNo ratings yet

- Cyber Incident Risk in CanadaDocument51 pagesCyber Incident Risk in CanadaAmr.H HindawyNo ratings yet

- Supply Chain Risk Management - EditedDocument8 pagesSupply Chain Risk Management - EditeddexterNo ratings yet

- Schadenspiegel 302-07709 enDocument20 pagesSchadenspiegel 302-07709 enselvajanarNo ratings yet

- An Agile and Diversified Supply Chain: Reducing Operational RisksDocument13 pagesAn Agile and Diversified Supply Chain: Reducing Operational RisksSukma Yunia RahmafaniNo ratings yet

- Chapman Et Al 2002 Identifying and ManagingDocument6 pagesChapman Et Al 2002 Identifying and ManagingLê Thị Hiền VyNo ratings yet

- Article 2Document18 pagesArticle 2aravind sharenNo ratings yet

- University of Westminster Coursework Cover Sheet Ca1Document5 pagesUniversity of Westminster Coursework Cover Sheet Ca1f5dbf38y100% (1)

- Thesis Topics in Disaster Risk ManagementDocument6 pagesThesis Topics in Disaster Risk Managementchristinaboetelsiouxfalls100% (2)

- Building Resilience in Businesses & SupplyDocument18 pagesBuilding Resilience in Businesses & SupplyAhmadNo ratings yet

- Hamza Aslam SCM A-3Document9 pagesHamza Aslam SCM A-3Bilal AslamNo ratings yet

- 2 Russia PDFDocument39 pages2 Russia PDFHajar NAJINo ratings yet

- About Plants and ScienceDocument9 pagesAbout Plants and SciencesandovalazellamavisNo ratings yet

- Enterprise Risk Management A DEA VaR Approach in Vendor SelectionDocument15 pagesEnterprise Risk Management A DEA VaR Approach in Vendor SelectionFrancescoCardarelliNo ratings yet

- University of Huddersfield Repository: Original CitationDocument17 pagesUniversity of Huddersfield Repository: Original CitationjomartaNo ratings yet

- Understanding Risks in Perishable Supply Chains and Risk Mitigation Strategies in The Context of A Large Fruitvegetable Retail StoreDocument5 pagesUnderstanding Risks in Perishable Supply Chains and Risk Mitigation Strategies in The Context of A Large Fruitvegetable Retail StoreG Sunil KumarNo ratings yet

- Deci 12468 PDFDocument29 pagesDeci 12468 PDFDulanji PiumiNo ratings yet

- Dirty Profits IIDocument124 pagesDirty Profits IIOmar TiradoNo ratings yet

- Sociological FactorsDocument34 pagesSociological FactorsHaris Ali KhanNo ratings yet

- Kumar & M Closed Loop Supply ChainDocument9 pagesKumar & M Closed Loop Supply ChainElleNo ratings yet

- Paper Cyberrisk 2014 PDFDocument27 pagesPaper Cyberrisk 2014 PDFYusfarhan Che PaNo ratings yet

- Risks in International LogisticsDocument7 pagesRisks in International LogisticsPranshik WarriorNo ratings yet

- Cybersecurity Risk Management in SMEs: A Systematic ReviewDocument6 pagesCybersecurity Risk Management in SMEs: A Systematic ReviewGaurav KumarNo ratings yet

- J of Ops Management - 2021 - Shen - Strengthening Supply Chain Resilience During COVID 19 A Case Study of JD ComDocument25 pagesJ of Ops Management - 2021 - Shen - Strengthening Supply Chain Resilience During COVID 19 A Case Study of JD ComUshan De SilvaNo ratings yet

- Dimensions of Business Resilience in The Context of Post-Disaster Recovery in Davao City, PhilippinesDocument31 pagesDimensions of Business Resilience in The Context of Post-Disaster Recovery in Davao City, PhilippinesStrat CostNo ratings yet

- 19 (Service) Kathawala2003 PDFDocument10 pages19 (Service) Kathawala2003 PDFkaggle practiceNo ratings yet

- Supply Chain Risk ManagementDocument8 pagesSupply Chain Risk ManagementWandere LusteNo ratings yet

- Xviii Paper 50Document15 pagesXviii Paper 50AsimNo ratings yet

- AKM Lanjutan 7Document8 pagesAKM Lanjutan 7busyaib syamsul sirotNo ratings yet

- Digitalization As Means To Overcome Supply Chain DisruptionsDocument11 pagesDigitalization As Means To Overcome Supply Chain DisruptionsLân LêNo ratings yet

- Commodity Exposure IndexDocument12 pagesCommodity Exposure IndexNeil McindoeNo ratings yet

- Current Affairs 8th Nov 2023 Amigos IasDocument6 pagesCurrent Affairs 8th Nov 2023 Amigos Iasmunnatechchannel01No ratings yet

- SCM issues during the COVID-19 pandemicDocument7 pagesSCM issues during the COVID-19 pandemicHusen AliNo ratings yet

- Erika (RRL)Document9 pagesErika (RRL)Christian Raff AgcaoiliNo ratings yet

- Thesis On Weather DerivativesDocument8 pagesThesis On Weather Derivativesamandawilliamscolumbia100% (1)

- Financial Losses and Flood Damages Experienced by SMEs: Who Are The Biggest Losers Across Sectors and Sizes?Document19 pagesFinancial Losses and Flood Damages Experienced by SMEs: Who Are The Biggest Losers Across Sectors and Sizes?Zeyu YaoNo ratings yet

- Msci Research PaperDocument7 pagesMsci Research Paperfvf442bf100% (1)

- Economics Cyber Effects UkDocument79 pagesEconomics Cyber Effects UkPrabhu Karthick Chezhian PGPMX 2021-23 Batch 1No ratings yet

- Supply Chain Decision MakingDocument14 pagesSupply Chain Decision MakingQadri HasanulNo ratings yet

- Admsci 13 00257Document15 pagesAdmsci 13 00257Ali ZakirNo ratings yet

- Hazard and Near-Miss Reporting - An Analysis of The Effectiveness of Increased Error ReportingDocument12 pagesHazard and Near-Miss Reporting - An Analysis of The Effectiveness of Increased Error ReportingBandar AlmalkiNo ratings yet

- Promoting Integrity in the Work of International Organisations: Minimising Fraud and Corruption in ProjectsFrom EverandPromoting Integrity in the Work of International Organisations: Minimising Fraud and Corruption in ProjectsNo ratings yet

- OM Unit 2.1 OverviewDocument28 pagesOM Unit 2.1 OverviewMapuia Lal PachuauNo ratings yet

- Case Digest - The Corporate Brand: Help or Hindrance?Document4 pagesCase Digest - The Corporate Brand: Help or Hindrance?Nic SaraybaNo ratings yet

- Handouts ACCOUNTING-2Document39 pagesHandouts ACCOUNTING-2Marc John IlanoNo ratings yet

- Commercial Bank of Ethiopia SWOT Analysis OverviewDocument5 pagesCommercial Bank of Ethiopia SWOT Analysis OverviewhayelomNo ratings yet

- Manual Part I Business SimDocument30 pagesManual Part I Business SimJonasNo ratings yet

- HRM NewDocument39 pagesHRM NewWaqar AhmadNo ratings yet

- Is The Rookie Ready ?: Case Study-Group 8Document6 pagesIs The Rookie Ready ?: Case Study-Group 8Sourish Re-visitedNo ratings yet

- June 15 2013 It Has Been Two Weeks Since Covolo DivingDocument1 pageJune 15 2013 It Has Been Two Weeks Since Covolo DivingAmit PandeyNo ratings yet

- Annual Report Klia 2011Document410 pagesAnnual Report Klia 2011Mohd Nazmi CeoNo ratings yet

- Employee Involvement in Total Quality ManagementDocument3 pagesEmployee Involvement in Total Quality ManagementFay Abudu100% (1)

- Fire Safety V1010.1Document1 pageFire Safety V1010.1Vikas YamagarNo ratings yet

- HR Assignment Vodafone 3Document12 pagesHR Assignment Vodafone 3OsaheneNo ratings yet

- 01 Entrepreneurial Skills II Revision NotesDocument4 pages01 Entrepreneurial Skills II Revision NotesAbhishek GuptaNo ratings yet

- Fired For Cheating On Employer TestDocument3 pagesFired For Cheating On Employer TestDarlyn ValdezNo ratings yet

- CNO Urged to Change NCLEX Retake, Temporary Registration PoliciesDocument4 pagesCNO Urged to Change NCLEX Retake, Temporary Registration PolicieskennthisraelNo ratings yet

- Philippine Supreme Court rules on airline pilots association disputeDocument11 pagesPhilippine Supreme Court rules on airline pilots association disputeDanielle Ray V. VelascoNo ratings yet

- Unit IIDocument20 pagesUnit IIImran Raja100% (1)

- 12 Hour Shifts and The Effect On Law Enforcement Officers - EditedDocument4 pages12 Hour Shifts and The Effect On Law Enforcement Officers - EditedPaula JonesNo ratings yet

- Fluor Corporation: Presented byDocument18 pagesFluor Corporation: Presented byEimidaka PohingNo ratings yet

- About Apics Cpim PresentationDocument32 pagesAbout Apics Cpim PresentationdeushomoNo ratings yet

- Project Manager Operations in Tampa ST Petersburg FL Resume Amy LaffeyDocument3 pagesProject Manager Operations in Tampa ST Petersburg FL Resume Amy LaffeyAmyLaffeyNo ratings yet

- Presentation On RecruitmentDocument10 pagesPresentation On RecruitmentRAJ KUMAR MALHOTRANo ratings yet

- Entrepreneurship Studies GST 203 - Lecture 4 Nigerian Business EnvironmentDocument9 pagesEntrepreneurship Studies GST 203 - Lecture 4 Nigerian Business EnvironmentchisimdiriNo ratings yet

- Capstone II - Redone Final Case AnalysisDocument15 pagesCapstone II - Redone Final Case Analysisapi-583140565No ratings yet

- Proposal - Budget - Guidelines - Revision 1-10Document9 pagesProposal - Budget - Guidelines - Revision 1-10munyatsungaNo ratings yet

- Schlumberger Recruiting DeclarationDocument3 pagesSchlumberger Recruiting DeclarationnikalisNo ratings yet

- Human Resource ManagementDocument3 pagesHuman Resource ManagementQuestTutorials BmsNo ratings yet