Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Managing Personal Human Capital

Uploaded by

Marco DiazOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Managing Personal Human Capital

Uploaded by

Marco DiazCopyright:

Available Formats

Pergamon

European Management Journal Vol. 21, No. 1, pp. 110, 2003 2003 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved. Printed in Great Britain doi:10.1016/S0263-2373(02)00149-4 0263-2373/03 $30.00 + 0.00

Managing Personal Human Capital: New Ethos for the Volunteer Employee

LYNDA GRATTON, London Business School SUMANTRA GHOSHAL, London Business School

The relationship between individual employees and their employing organizations is undergoing fundamental changes. Increasingly, the employee is less a malleable resource for the company and more a mobile investor of his or her own human capital. Dening human capital as the composite of an individuals intellectual, social and emotional capitals, this article suggests some new ethos that such volunteer employees need to adopt as they take greater personal responsibility for both developing and deploying their personal human capital. 2003 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved. Keywords: Human capital, Volunteer employees, Career success, Employing organizations, Employees industry. The new entrants prefer working in teams, demand an exciting and stimulating work environment and, most importantly, value autonomy in career. Many have seen their parents sacrice their personal needs to meet company requirements. They have vicariously experienced the tragedies of the organizational man (Whyte, 1956) and are determined not to fall victim to the forces of depersonalization in the traditional model of individual-organization relationship. These changes in the relationship between the employer and the employee echo a broader revolution which is reshaping social institutions all around us. At the heart of this revolution lie the democratizing forces that push for modernity. The concept of democracy is built around some foundational principles: the creation of circumstances in which people can express their potentialities and their diverse qualities; protection from the arbitrary use of authority and power; involvement of people in determining the conditions of their association; and expansion of opportunity to develop available resources.1 These forces of democratization are transforming individuals relationships at all levels with other individuals, with organizations, and with broader collectives such as the State. In this sense, the changes we are witnessing in the employment relationship are very similar to the changes Anthony Giddens has described in the nature of human intimacy and in the institution of marriage2 the shift, for example, from investing in life-time relationships to serial monogamy characterized by a series of close relationships governed by the expectation that these relationships need to be made to work, yet will inevitably not last.3 These changes also follow closely the

1

Introduction

We are witnesses to some sweeping changes in the nature of the relationship between individuals and organizations. The geneses of these changes lie not in the managerial rhetoric to empower the workforce: they have occurred as a response to fundamental changes in society, in the nature of labor markets and in the talents and aspirations of individuals. The present temporary reversal notwithstanding, changes in the demographics of most countries have placed young talent at a premium across the globe, and with this war for talent has come the opportunity for the new generation to shape the way they work. At the same time the generational markers of those entering the workforce are very different from those of the baby boomers who are currently running

European Management Journal Vol. 21, No. 1, pp. 110, February 2003

PERSONAL HUMAN CAPITAL

implications that Deepak Lal has traced of the rise of individualism on the social structure and economic functioning of nations.4 The concept that links these various elements of democratization is the primacy of individuals and their capacity to behave with autonomy, i.e. their capacity to be self-reective and self-determining to deliberate, judge, choose and act upon possible courses of action (Held, 1986, p. 270). At the same time there has been an enormous ourishing of variety in the models of working: work part-time or fulltime; work for a large company or a small start-up; work as a freelance or as a member of the core; build a company or work for a company. The aspect of the ongoing transformation from an industrial to a postindustrial society that perhaps deserves the greatest celebration is the blossoming of this variety and the accompanying liberation of the individual from the iron cages of both organizational and occupational hierarchies. Success today can come from a much more diverse set of occupations than in the past with much less predictability ex-ante. With the broadening of the routes to economic prosperity, there has been the inevitable broadening of social respectability too. In other words, together with the growing sense of autonomy among individuals, there is also a growing variety of work opportunities for people to choose from. How have companies responded to these broad changes? For many the mantra of employability provided a useful over-arching philosophy to downsize in the face of renewed competitive pressure and the need for greater exibility of skills. They could and would no longer promise lifetime employment, but their side of the deal was to support the individual employee to build his or her human capital. In reality it has proved to be enormously difcult to deliver this deal in an institutional form.5 So, in many cases, company investment in job-related training has decreased rather than increased, and the opportunities for broadening beyond current job roles have narrowed rather than widened. Bad news perhaps, but we believe these trends are a harbinger of what is to come and an important wake up call to employees. In previous generations the conventional practice was for the employee to play the part of the innocent with the employer as the sophisticate. The relationship today is reversed; the innocent plays the sophisticate. This places responsibility for development of the self squarely in the hands of the possessor, in the individuals rights of self-expression. It is increasingly individuals who control their development, their careers and their destinies, not the organizations that employ them. This does not mean that people continuously change jobs some do, and some dont. But they take charge of their careers, which essentially means that they actively manage the processes of developing and deploying their own

2

resources. In essence, the traditional paternalistic model of employment is being replaced by a volunteer model, in which the interests of both the individual and the organization have to be met and commitment to work, which once could perhaps be assumed, has now to be negotiated and bargained for. At least for managerial and professional careers, this is the growing trend all over the world. So given both autonomy and variety, how does the individual construct a work life of meaning? The emerging volunteer model of employment relationship requires the creation of a whole new language of development. Much of the historical discourse about development has been around what the organization can do for the individual. In this article we examine what individuals can do for themselves to construct novel ethics of day-to-day work life while simultaneously building and leveraging their personal resources.

The Three Elements of Human Capital

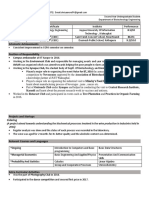

The notion of individuals participating in the democratization of work implies they have sufcient resources to participate in an autonomous way. In considering the notion of resources we have used the term human capital. This refers to things people have. But, people have, are and do many things, including many wonderful things, that have nothing to do with human capital. The operating word here is capital i.e. a productive resource and the adjective is human. What things do people have that are productive resources? What is it about people that translates into value for themselves and the organizations of which they are part? We believe that there are three kinds of resources that people possess which, collectively, constitute their individual human capital (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Human Capital consists of the Intellectual, Social and Emotional Capitals of Individuals and Organizations

European Management Journal Vol. 21, No. 1, pp. 110, February 2003

PERSONAL HUMAN CAPITAL

The rst element is intellectual capital. It refers to fundamental individual attributes such as cognitive complexity and the capacity to learn, together with the tacit and explicit knowledge, skills and expertise an individual builds over time. In the recent past, much management attention has been paid to this issue of intellectual capital, and rightly so.6 For organizations, knowledge rather than money is increasingly the key competitive differentiator certainly in service industries like consulting, investment banking, IT services and so on, but also, increasingly, in manufacturing-based businesses like pharmaceuticals, consumer electronics, and electrical machinery where, historically, large asset bases and strong balance sheets had held the key to success. This has naturally created a large premium for the intellectual capital of individuals. But, if people with great knowledge and expertise were all it took for achieving outstanding business performance, a society of Nobel laureates would have created the most successful global company. Knowledge is an essential element of human capital, but not all that there is to it. The second element of human capital is social capital7 which is about who one knows, and how well one knows them. And, just as cognitive complexity and learning capacity provide the underlying individual traits on which specialized knowledge and skills are grounded, similarly sociability and trustworthiness provide the anchors for developing and maintaining a network of relationships. These relationship networks constitute a form of capital because they provide access to the resources members of the network possess, or have access to. This is why those who have studied at Tokyo University, Oxford, Ecole Polytechnic or MIT tend to have an advantage over others irrespective of whether they are smarter than the others or not, they tend to have friends in inuential positions in other organizations to access new business opportunities and to solve problems. This is also why Silicon Valley and other global hot spots yield such enormous value for individual members of these communities. The depth and richness of these connections and potential points of leverage build substantial pools of knowledge and opportunities for value creation and arbitrage.8 But specialized knowledge and a great network of friends are not enough to get things done, to move into action, individuals need one more thing. That is emotional capital.9 Like aspects of intellectual capital, individual emotional capital is underpinned by fundamental traits such as self-awareness, self-esteem and personal integrity. Individuals need self-condence, based on self-esteem, courage and resilience, to convert their knowledge and relationships into effective action. These different elements of human capital (see Table

European Management Journal Vol. 21, No. 1, pp. 110, February 2003

Table 1

Elements of Human Capital of Individuals Social capital Network of relationships Sociability Trustworthiness Emotional capital Self-awareness Ambition and courage Integrity Resilience

Intellectual capital Cognitive complexity Learning capacity Specialized knowledge and skills Tacit knowledge

1) are highly inter-related; it is the combination, the feedback-loops and connectivity which bring advantage. Social capital, in the form of extensive, uid and reciprocal relationships with people, helps individuals develop intellectual capital by accessing the knowledge and skills that those people possess.10 Emotional capital brings the integrity and self-awareness to build open and trusting relationships which underpin the creation of social capital. The learning propensity of intellectual capital can be a driver for self-development, resulting in the self-awareness of emotional capital. And within this reinforcing feedback loop, the self-knowledge built through open and meaningful relationships further enhances selfawareness and self esteem. Together, emotional, social and intellectual capitals are the basis for building strong and supportive relationships, and for developing the courage and grit necessary for entrepreneurship and action taking. In turn, action leads to knowledge people learn by doing, by experimenting, by testing out ideas. The reverse is also true knowledge and skills are a prerequisite for effective action. A similar kind of symbiotic relationship exists among all the elements of human capital. But, at the same time, they also create tensions and contradictions. While knowledge facilitates action, it can also impede action. Knowing can come in the way of doing. Relationships facilitate action but commitments to relationships can also prevent necessary but unpleasant actions.11

Managing Personal Human Capital

The challenge of competing on human capital is the challenge of managing this interactive cycle of building and leveraging intellectual, social and emotional capitals. This is just as true for individuals as it is for organizations. For individuals, the democratization of work life requires each to take responsibility for his or her own development, instead of passively relying on others to manage it for them. In a fast changing world, all the elements of human capital erode rapidly knowledge becomes obsolete unless it is updated, relationships weaken unless they are continuously

3

PERSONAL HUMAN CAPITAL

refreshed, self-efcacy and courage diminish unless exercised. Each individual has to become aware of these risks of diminution and make active choices about where to work and what to build based on that awareness. In recent times, few business leaders have achieved as much recognition and success as Andy Grove, the Chairman of Intel. Starting his life in the United States as a penniless emigrant from Hungary, Groves career is an epitome of not just professional accomplishments but also of lasting contributions building a highly-admired institution and, through it, playing a key role in the development of the digital world. Groves rst advice to all employees of Intel is worthy of attention:

No matter where you work, you are not an employee. You are in business with one employer yourself in competition with millions of similar businesses worldwide Nobody owes you a career. You own it as a sole proprietor.12

Smith and Frederic Taylor led to clear boundaries within occupations and specializations, as well as a hierarchy among them. The incentives were not for discovering ones own talents and propensities and becoming the best one could be, but for participating in the highest-ranking occupation one could get admission to. The pathologies of the organization man that William Whyte portrayed so brilliantly (Whyte, 1956) was indeed broader than the subjugation of the individual to the needs of the organization it encompassed an overarching subjugation of the individual to the socially-dened hierarchy of occupations. But with the transformation of the post-industrial society has come variety and liberation from occupational hierarchies. If individuals do indeed volunteer then what is the basis of this volunteering, and given the new autonomy, on what basis is meaning constructed? Jung uses the term individuation to describe the opportunity each individual has to reach his or her fullest possible development, to be whole. The vocatus for all individuals, according to him, is to become themselves as fully as they are able; the challenge is to nd out how.13 The autonomy and variety available to the volunteer bring enormous potential for joy and satisfaction through the discovery of the vocatus. Work represents a large occasion for creating meaning, or its denial, and in each individuals life journey, work inevitably plays a central role. But how can individuals access their deepest needs and values? A starting point is to have a broad frame of reference and Jungs typology of preferences, operationalized in the Myers Briggs Type Inventory, has brought clarity for many people.14 The attitude of introversion and extroversion, for example, describes whether reality is processed by an individual as something within or something out there. Accordingly, an extroverted sensation type is likely to be drawn to the outer world and derive greater satisfaction from work as a project leader. An introverted thinking type might enjoy being an academic but would be, in all likelihood, unhappy and unsuccessful as a salesperson. Another important support mechanism for self-discovery is to create a feedback rich context. For some people, developing this level of self-awareness is facilitated by the organization. Many companies have introduced 360 feedback, based on team members and colleagues reporting on an individuals performance and attitudes. For most, it is something that the organization does for them. But it does not have to be that way. At both Hewlett Packard and Intel, for example, individuals actively seek feedback by emailing their colleagues in the immediate and extended networks, asking for information and opinions about themselves. This information is not routed via the organization, but is elicited, sythesized and discussed by individual employees. Analytic frames such as the Myers Briggs instrument

European Management Journal Vol. 21, No. 1, pp. 110, February 2003

Perhaps there is an element here of the Hobbesian war of all against all but, in a competitive, knowledge-based economy, this is the starting point for managing human capital at the individual level. Each individual must now accept the responsibility for managing his or her personal human capital. Because of this responsibility, participants in the new volunteer model for individual-organization relationship will increasingly have to adopt four new personal ethos. First, the opportunity created by the forces of autonomy and variety will place a premium on individuation, and, therefore, on peoples courage to understand and be who they are. Second, to manage the interactions between development and deployment of human capital, there is a need for a changed mindset: instead of thinking of themselves as assets, to be used by the organization, individuals must see themselves as investors in the company, not unlike the investors of other forms of resources, such as nancial capital. Third, to continuously develop their own knowledge and skills, they have to open their hearts and minds to the invigorating force of continuous learning an ethos that, following Jack Welchs colorful term, we have labeled as everyday, being the dumbest you can be. And, nally, with the increasing value of innovation and new ideas, they have to consciously position themselves at the intersections of intellectual and social domains, so as to be able to bridge diverse spheres of knowledge and other kinds of resources.

Ethos 1: The Courage To Become Who You Are The industrial society was built around a logic of subdividing and specializing the occupations and contributions of individuals. Over time, the logics of Adam

4

PERSONAL HUMAN CAPITAL

and tools such as receiving detailed feedback have a role to play in developing personal awareness, but this data can only be accessed through a reective mind-set where feelings and emotions are acknowledged. Many individuals nd this very hard to do, and are more condent in their evaluative, thinking mode15 To access values and preferences, however, requires the development of the less developed feeling function and the self-reection which comes from it. This is achieved through listening more closely to ones own feelings and those of others, acknowledging the feelings one has about a situation, and by creating periods of self-reection to promote this inner dialogue. The reason most people develop a learned helplessness in dealing with their feelings is to avoid the doubts and discomforts feelings often create. The old paternalistic employment contract may have created doubts and discomforts, but these could be attributed to the vagaries of the company. Variety brings opportunities for developing multi-faceted lives, autonomy brings the realization that these periods of doubt and discomfort are inevitable. The life of the volunteer will inevitably involve anxiety and loss: when they stretch too far and fail; when the risks they take leave them vulnerable and alone; when they are forced to confront their values and aspirations periods which Jung termed the swamplands of the soul.16 It is possible to manage this anxiety through the defenses of denial or repression. Having the courage to become who you are comes from the realization that in each of these swampland states there is a developmental task, and of understanding that doubt is the necessary fuel for change, and therefore growth.

a deep understanding of current capabilities. The same is true for building great personal human capital. From personal reection comes an understanding of goals, values and aspirations. The next challenge is to translate these goals in terms of their human capital requirements what kind of knowledge and skills will be needed, what relationship networks will be vital, what will be the emotional demands? While life is never so linear, without a rough plan, one cannot cope with the unexpected exigencies and still maintain course. Indeed, people engage in such planning routinely for their personal nancial capital, but not for their personal human capital. The challenge of competing on human capital, above all is the challenge of counteracting that state of apathy with regard to any individuals most important asset. Managing personal human capital as if it was a business is about having absolute clarity of where to best allocate scarce resources (personal human capital) for short and long-term leverage. It is about choosing among equally attractive options which may yield different benets. Increasingly the volunteer employee will want to make an informed choice of allocation by accessing deep information about the potential of different work options for building their intellectual, emotional and social capitals. While in many companies there is tacit knowledge about the development potential of work options such as projects, some companies have sought to make this knowledge more widely available. At Applied Technology, for example, new engineers rotate through a series of ve-week projects designed to give the recruits a taste of the different parts of the business. While working on these projects, they condentially share via the companys intra-net their views on the work and the capability of the project leaders to mentor and coach. This sharing deepens the engineers information and increases their capability to make choices and to actively manage their personal human capital. At the core of creating personal human capital is the determination to take personal responsibility for development, and a preparedness to invest personal resources in development. This may be the nancial resources to participate in training programs. It is more likely to be a resource trade-off between capitalizing on the returns from current human capital and investing in development of new human capital. Structured training programs have some impact on the creation of personal human capital, but the primary impact arises from day-to-day experiences in work: from mentors who become talking partners; from sponsors who open new opportunities; from stretching and challenging projects; from engaging and stimulating colleagues who are prepared to share their knowledge; from feedback rich working environments. For the determined investor the choices are where and whom to work with. Businesses are compelled to report on their manage5

Ethos 2: From An Asset To An Investor Taking the courage to become who one is demands a reective, conscious process of self-development. In the old paradigm much of the role of development was assumed by the company, with employees simply following the laid down trajectories. But as democratization of the work place grows, and with increasing autonomy and variety, the old paternalisms are no longer valid. Individuation requires a more conscious and continuous building of intellectual capacity, of emotional strengths and of social networks. Hence, the second ethos: individuals must move from viewing themselves as simply an asset to the business, to becoming investors in the business. They invest in building their personal human capital which, in turn, they invest in the business in which they choose to work. Investors have a particular view of a business. If building human capital is a business, then the same logic applies the logic of having a broad purpose and vision, of resource allocation, of exibility and adaptability. Great businesses are built from a broad purpose and

European Management Journal Vol. 21, No. 1, pp. 110, February 2003

PERSONAL HUMAN CAPITAL

ment or nancial capital, but the capacity to create human capital is still shrouded in mystery. The investor, therefore, has to become an acute observer and seeker of human capital related information. They need specic answers to the following questions: what is the companys history of mentoring? How much time do the leaders of the business spend on coaching activities? Are senior people willing to sponsor young people? Is any part of the remuneration of team leaders determined by their ability to attract and retain talented people? What is the proportion of exciting projects? How is membership to projects assigned? What is the knowledge base of people? How is feedback on performance given and received? Do people trust each other? What is the individual latitude of discretion? In business, people make hard decisions about the allocation of scarce resources, making deals, negotiating and bargaining for what they believe is right. Actively building personal human capital requires the same up-front attitude: the attitude of keeping options open; of developing general, portable skills rather than company-specic skills; of having the courage to make substantial personal investments in knowledge acquisition; of negotiating hard for the opportunity to build social networks. The investor mind set is more active, more self aware, more courageous. These are the most obvious parallels between managing personal human capital and managing a business: the importance of purposeful choice; of making tough decisions on the allocation of scarce resources; and the rationality of planning and purpose. But the analogy extends further than that. Companies often suffer by becoming prisoners of the past unable to free themselves from their history, they remain lumbering and inexible. The ties of the past create strategic inertia: processes and routines, once useful, become moribund and bureaucratic; values and norms become ossied and inappropriate. The same often happens to people. The escape from such ossication lies in the imaginal capacity that all individuals possess but many do not use. While individuals are limited by their complexes to repeat historic response patterns, they can enlarge their vision of the possible and learn to overcome the constraints of the past. To be adaptive, businesses have to confront and discard those aspects of their heritage that are no longer appropriate. Similarly, to develop as a person, it is sometimes necessary to cross lines once thought too formidable. This may entail transgressing a mentors will or a colleagues hopes and aspirations; it may mean no longer clinging to impossible fantasies, or freeing oneself from routine and, therefore, comfortable ways of behaving. Each individual is constrained within the narrow connes of a specic combination of time, place and history. In a world of autonomy and variety, each

6

individual is obliged to nd his or her own way, and crossing over sometimes confronts the need to stand against the forces of personal history.

Ethos 3: Everyday, Be The Dumbest You Can Be Over the last four years, the two authors have jointly run an executive program. It is a consortium program, consisting of six large, highly visible, global companies. Each company sends a team of six very senior-level general managers to the program, which runs in short modules over a ten-month period. The basic philosophy of the program is built around the concept of learning from one another individuals learning from their peers in companies from very different businesses, cultures and histories, as well as each company team learning from the perspectives and practices of the other companies. Over the ten month period, we travel around Asia, the Americas and Europe, visiting each company, looking at its operations, talking to a wide range of people all in the hope of maximizing both individual and collective learning from these experiences. Over the four years that we have run the program, both of us have been struck by one remarkable difference among the individual participants in how they approach these visits. A vast majority use their critical faculties to see what is wrong, what is not working as well as it might, and where the company practices are inferior to their own. At the end of the company visit, these participants summarize their critiques in sharp, focused ways. Their feedback is usually both uncomfortable and useful to the managers of the host units. But there are a few typically very few who go about the visits very differently. They look for what is working, where the practices of the company are better than their own, and what can be learnt during the visit that can be implemented with some benets in their own organizations. Inevitably, they nd such areas sometimes in very specic actions, such as some unique aspects of the companys quality management processes, and sometimes in much broader aspects such as the companys ability to create a high energy work environment. They ask sharp questions to ensure that they fully understand why and how the practices work as well as they appear to do, often going down to a level of detail that the others consider to be trivial. Members of the rst group are smart. They use their knowledge and skills to see what is missing, where their own knowledge and expertise are superior. The members of the second group are smarter. They exploit the opportunity to learn and to enhance their own human capital. According to GEs Jack Welch, the essence of a boundaryless, learning organization is that EveryEuropean Management Journal Vol. 21, No. 1, pp. 110, February 2003

PERSONAL HUMAN CAPITAL

day, people are the dumbest they can be. As he explains, there is always someone who is doing something better than us. The challenge is to be open to the learning opportunities that life provides everyday. Some individuals tend to be inherently more open to such learning than others, as a personality trait. But it is a skill that can be improved through conscious effort. The volunteer ethos requires each individual to become a determined developer, to continuously learn. At the heart of this determined development are three core learning processes that individuals use: application, induction and reection. The processes are the learning engines through which personal human capital is continuously refreshed and created. Application starts from exposure to broad, contextfree concepts or theories, such as core competency, which are then applied to a particular, context specic situation, relevant to the individuals own company or job. As a learning process, it is based on what Don Schon has described as technical nationality (Schon, 1983). Induction, the second learning process, is driven by the search for patterns and consistencies across different experiences what Mintzberg has called detective work and then the generalization beyond data, which he described as the creative leap (Mintzberg, 1979). Much of the learning from trials and experimentation follows an inductive process, based on tentative formulation of hypotheses, and enriching them through testing and feedback. Finally, reection, the third learning process, is built on in-depth understanding of a particular and context-specic situation that ultimately leads to insight and intuition an outcome that is very different from both the knowledge-acquisition and internalization process of application and the creative generalization from diverse experiences through induction. Insights generated through deep reection on one situation do not reveal general truths; instead they shape perspectives and assist in identifying, dening and framing problems. As argued by Schon, reection is an alternative route to generalization premised not on scientic analysis, but on what, for want of a better term, may be best described as the development of wisdom. To become a determined learner, individuals need the capacity to learn through all three processes. To learn through application, they will need continuous exposure to the latest ideas and concepts, and must be willing to invest signicant personal resources to stay current in their areas of interest. Part of these investments may be in the form of time and money to participate in on-going educational activities, but more of it is likely to take the form of trade-offs between appropriating returns from their existing knowledge and committing resources to develop new knowledge. Reading, taking sabbatical leaves for retraining, and becoming part of the networks in which relevant new knowledge is created are all

European Management Journal Vol. 21, No. 1, pp. 110, February 2003

activities that support learning through the application process. Important as it is, however, application is likely to contribute a relatively small part of the total learning of the determined developer: he or she is likely to obtain greater leverage from both induction and reection. These are also the learning processes that most people tend to be less comfortable with, simply because of the dominance of application in the learning process of formal education. Both induction and reection require intellectual curiosity together with the courage and personal sense of autonomy to form ones own theories. While the quality and usefulness of such theories depend, to some extent, on individual attributes such as creativity, capacity for pattern recognition and cognitive complexity, the courage to engage in such theory-building endeavors can be enhanced through both practice and reinforcement from mentors who become thinking and talking partners, and stimulating colleagues who help create an intellectually alive and challenging environment that facilities actionlearning. For the determined developer choosing feedback-rich, stimulating work and knowledgeable mentors and sponsors is crucial to building personal human capital.

Ethos 4: Work The Boundaries About half a century ago, Joseph Schumpeter, the Austrian economist, had a profound insight. Progress comes from new combinations. It was this insight that led him to an understanding of the process of creative destruction that lies at the heart of competitive economies (Schumpeter, 1934 (reprinted in 1962)). New combinations of existing knowledge create new knowledge. The combination of biology, physics and chemistry creates molecular biology. Combination of technical and marketing knowledge creates winning new products. Understanding the needs of manufacturing and of customers leads to innovative logistical solutions. The same is true of relationships. The individual who bridges two disparate groups of people who are not connected among themselves gets the benets of brokerage across them. In academic terms, this is called structural holes gaps in relationship networks that yield productive bridging opportunities.17 Social capital is developed through networks built upon trust and reciprocity. It is these networks which can bring the knowledge and excitement that propel individuals to action. Skilful builders of networks are passionate about people and have the emotional capacity to create strong, intimate relationships with others. But building networks comes at a price; in

7

PERSONAL HUMAN CAPITAL

particular the resource cost of maintaining networks which can fast erode. Here the individual is faced with an investment dilemma; whether to put his or her resources into establishing strong ties with a small network of closely linked individuals, or to invest available time and resources for developing networks of weak links to many, disparate people. Both can bring benets. Strong networks have the advantage of focusing attention on a smaller group of people and, in doing so, creating the intimacy, trust and reciprocity which provide the foundation for transference and combination of rich, tacit knowledge in multiple ways. These strong links are crucial to the development of deep, specialist expertise. But establishing and maintaining these strong exclusive networks reduce the opportunity for establishing a wider network; and while they can yield tacit knowledge, these tight networks have fewer people and, typically, a high degree of redundancy since there is so much shared common knowledge. In short, while the individual acquires greater tacit, specialist knowledge, he or she is unlikely to encounter knowledge from outside a limited domain. On the other hand, individuals who develop multiple weak networks have the opportunity to access a wider diversity of knowledge and therefore the possibilities of connecting these networks and their activity domains to create value through new combinations.18 This is why working at the boundaries or, rather, working the boundaries, is so often so benecial for both building and leveraging ones human capital. Bridging across two disparate groups say, R&D and marketing helps build new knowledge, skills and insights that neither group has. Bridging between two industries creates new opportunities as they converge. Bridging the worlds of science and venture capital yields new business possibilities. The arbitrage opportunities in these loose networks arise from the information asymmetry across the networks and the value of bringing ideas and knowledge from one to another. This is not easy, however. It is more comfortable to stay within the bounds of ones own kind of people, who do similar things and behave in similar ways. Membership of multiple networks involves a great deal of effort. Similarly, bridging across diverse knowledge domains is more complex than maintaining ones specialization within a single domain. But, biographies of successful entrepreneurs, CEOs, authors or academics are replete with tales of bridging in action. The starting point for bridging and also the most difcult step is to have the courage to put oneself in novel situations. Having been born and brought up in Boston, the prospect of spending three years in Tokyo is nerve wrecking, as is a move to marketing after having built a successful career in nance. Novel situations lead to a loss of all the comforts of known surroundings, familiar systems and old

8

associations. But, it is only from such starts away from the comforts of life as usual and into new and unfamiliar situations and surroundings that all bridging begins. The issue here is one of investing to build social capital through combining strong ties which yield rich, tacit knowledge while simultaneously investing in weaker ties with disparate groups capable of building ideas through combination. The strategy of investing and building social capital sounds instrumental, and in some aspects it does play back to the concept of investing in personal human capital as if it was a business. But while rationality and strategic choices may identify the balance to be struck between weak and strong ties, they do not of themselves assist in the subsequent development of these ties or the capacity of these ties to yield benet. The badge sniffer at conference gatherings, intent on establishing loose ties with those they consider important is no more likely to build these relationships than the individual who shuns these events. Even loose networks require a degree of trust and mutual reciprocity, which is leveraged through selfesteem. Similarly, establishing close network ties does not of itself create an opportunity to vacuum up tacit knowledge. Individuals can choose to give or to withhold their knowledge and when faced with a transactional mercenary, the likelihood is that they will withhold. It is the capacity for empathy and intimacy built from emotional capital which provides the context in which people choose to freely give and to receive. Fundamentally working the boundaries may and indeed should be conscious, but it is not transactional. It comes from a deep and passionate interest in people, from the capacity to give as well as to take. Networking without empathy fails to build either the intimacy which supports tacit knowledge sharing within strong links or the broad sociability which creates arbitrage opportunities across weak links.

From Human Capital To Meaningful Lives

In this article we have argued that fundamental changes are occurring in the nature of the relationship between individuals and the organizations of which they are members. At the heart of these changes lie the democratization of this relationship, stemming in part from increased personal autonomy and greater work variety. This democratization places enormous emphasis on individuals self awareness and courage to build and leverage their personal human capital. But it brings with it enormous promise. Autonomy and variety provide the opportunity for people to become who they are, to

European Management Journal Vol. 21, No. 1, pp. 110, February 2003

PERSONAL HUMAN CAPITAL

pursue their natural talents, to build meaning and to create more emotionally satisfying lives. It is necessary to relate this argument about peoples work lives to the broader context of the role work plays in modern life. Historically, people had at least three different spheres in their lives: the family, work, and a third place the pub in the U.K, community organizations in the US, the tea shops in China or India. Gradually, this third place is becoming a void because of a variety of disruptions including geographic mobility, the breakdown of communities, and a broader set of changes in societal norms and values that have tended to undermine its social and psychological viability.19 The third place used to serve as a key source of both the creation of meaning through social identity and personal pleasure. One was known there, and one could be who one was away from the evaluative and instrumental aspects of work, and from the duties and obligations of family. Progressive elimination of the third place and the associated enlargement of the work sphere have signicantly enhanced the need for work to be both more meaningful and more pleasurable. And for that to be the case, the gap between work and identity has to be reduced, which the growing variety of occupational opportunities now makes possible. Another related aspect of the on-going transformation of society that most observers have taken to be a cause for concern is the increasing sphere of winner-takes-all games. Whether an athlete, a manager or an academic, individuals are increasingly subject to an economic regime in which the very best corner most of the pay-off. These forces combine to create a very different context for career success there are many more games now, thereby providing more variety to match the variety of human preferences and pleasures, and each game offers large rewards for excellence and rapidly diminishing rewards thereafter. While most pronounced in the developed Western economies, this new context is rapidly spreading around the world, as a handmaiden of the evolving global market economy. Not only will ones personal human capital become more and more important in this new context, the courage to align who one is with what one does will become both more pleasurable and more protable. Aligning work with personal values, creating the vocatus doing what one likes has always been a precious human aspiration. It is increasingly becoming also the most effective strategy for personal success. At the end of the day, this is perhaps the most wonderful and satisfying aspect of competing on human capital while painful because of the need for continuous improvement of ones own knowledge, relationships and sense of self-efcacy,

European Management Journal Vol. 21, No. 1, pp. 110, February 2003

it aligns economic incentives with the very human propensity for creating meaningful lives by pursuing ones own convictions and passions.

Notes

1. We have followed closely Helds thoughts on democratization. See Held (1986). 2. See Giddens (1990, 1992). 3. Peter Cappelli draws the analogy with serial monogamy in his paper (Cappelli, 1999). 4. See Lal (1999). 5. There has been much evidence to suggest that organisations have not created exible internal labor markets or invested in the training of short-term skills. See for example, Pfeffer (1998). Detailed cases from seven large organisations also highlight the gap between rhetoric and reality. Lynda Gratton et al. (1999). 6. In 1997, three books were published all carrying the title intellectual capital; the programme for the 1999 Annual Meetings of the Academy of Management was dominated by sessions and papers on this topic. Clearly, for both managers and academics, this issue of knowledge management is now very much in the forefront of attention. Of the vast amount of literature on this topic, we have found the books by Quinn (1992) and Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) to be the most insightful from a practical point of view, and the articles by Spender (1996) and Grant (1996) as useful contributions and idea reviews, from an academic perspective. 7. The term social capital initially appeared in the context of community studies, highlighting the central importance of the networks of strong, cross-cutting personal relationships for the survival and functioning of city neighbourhoods. Since this early usage, this concept has been applied to elucidate a wide range of social phenomena, particularly its inuence not only on the development of human capital (see Coleman, 1988) but on economic performance of companies (see Baker, 1990), geographic regions (Putnam, 1995) and nations (Fukuyama, 1995). 8. For a rich description of the social capital networks in Silicon Valley, see Cohen and Fields (undated). 9. What we have termed here emotional capital borrows from disparate literature streams. At the individual level the notion of emotional intelligence has been described by Goleman (1995) and earlier by Salovery and Mayer (1980) and loosely dened as the ability to monitor ones own and others feelings and emotions. It is described as essentially individual and partly innate. By emotional capital we have broadened the concept to include integrity, to understand the emotions of others, and to acknowledge and be sincere about ones own emotions (Hochschild, 1983). We also describe an action element, the capacity to move into action through will and hope (Brockner, 1992). For recent and relatively comprehensive reviews of the role of emotions in organizational functioning and performance, see Fineman (1993) and Quy Nguyen Huy (1999). 10. For a detailed discussion on how social capital inuences the development of intellectual capital, see Nahapiet and Ghoshal (1998). 11. See Donald Sull (1999), for a rich and illustrated discussion of how commitment to relationships can prevent or delay action. 12. See Ghoshal and Bartlett (1997). 13. Jungs concept of individuation is described by Edward Edinger (1984). For deeper insights see Jung (19531979). 14. Jung rst described the personality types in Psychological Types, volume 6 (19531979). The Myers Briggs Type Inventory is discussed in Briggs Myers and Myers (1980). 15. People in business-related activities tend to be thinkers rather than feelers see Briggs Myers andMyers (1980).

PERSONAL HUMAN CAPITAL

16. 17. 18. 19.

As the authors also show, women are signicantly more likely to be feeling-orientated than men. See Hollis (1996). See Burt (undated). For an elaboration of this argument, see Granovetter (1973). Richard Pascale made this point in his unpublished paper (1995).

References

Baker, W. (1990) Market networks and corporate behavior. American Journal of Sociology 96, 589625. Briggs Myers, I.S. and Myers, P.B. (1980) Gifts Differing. Palo Alto, Consulting Psychologists Press. Brockner, J. (1992) Managing the effects of layoffs on survivors. California Management Review Winter, 927. Burt, R.S. (undated) Structural Holes: The Social Structure of Competition. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA. Cappelli, P. (1999) The new deal with employees and its implication for business strategy. Prepared for the IESE Conference on Strategy and Organizational Forms, June. Cohen, S.S., Fields G. (undated) Social capital and capital gains in silicon valley. California Management Review 14(2). Coleman, J.S. (1988) Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology 94, 95120. Edinger, E. (1984) The Creation of Consciousness: Jungs Myth of Modern Man. Toronto, Inner City Books. Fineman, S. ed. (1993) Emotions in Organizations. London, Sage. Fukuyama, F. (1995) Trust: Social Virtues and the Creation of Prosperity. Hamish Hamilton, London. Ghoshal, S. and Bartlett, C.A. (1997) The Individualized Corporation. Harper Business, New York. Giddens, A. (1990) The Consequences of Modernity. Polity, Cambridge. Giddens, A. (1992) The Transformation of Intimacy: Sexuality, Love and Eroticism in Modern Societies. Stanford University Press, Stanford. Goleman, D. (1995) Emotional Intelligence. New York, Bantam. Granovetter, M. (1973) The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology 73, 13601380.

Grant, R.M. (1996) Knowledge, strategy and the theory of the rm. Strategic Management Journal 17(S2), 109122. Gratton, L. et al. (1999) Strategic Human Resource Management: Corporate Rhetoric and Human Reality. Oxford University Press, Oxford. Held, D. (1986) Models of Democracy. Polity, Cambridge. Hochschild, L.E. (1983) The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA. Hollis, J. (1996) Swamplands of the Soul: New Life in Dismal Places. Inner City Books, Toronto. Jung, C. (19531979) Psychological Factors in Human Behaviour, The Structure and Dynamics of the Psyche. The Collected Works. Princeton University Press, Princeton. Lal, D. (1999) Unintended Consequences. The MIT Press, Cambridge. Mintzberg, H. (1979) An emerging strategy of direct research. Administrative Science Quarterly 211, 582589. Nahapiet, J. and Ghoshal, S. (1998) Social capital, intellectual capital and the organizational advantage. The Academy of Management Review 23(2), 242266. Nonaka, I. and Takeuchi, H. (1995) The Knowledge Creating Company. New York, Oxford University Press. Pascale, R. (1995) In search of the new employment contract. Unpublished manuscript presented at the Euroforum Conference Spain, 15-16 September. Pfeffer, J. (1998) The Human Equation: Building Prots by Putting People First. Harvard Business School Press. Putnam, R.D. (1995) Bowling alone: Americas declining social capital. Journal of Democracy 6, 6578. Quinn, J.B. (1992) Intelligent Enterprise. New York, Free Press. Huy, Quy Nguyen (1999) Emotional capability, emotional intelligence and radical change. Academy of Management Review 24(2), 325345. Salovery, P. and Mayer, J.D. (1980) Emotional intelligence imagination. Cognition and Personality 9(3), 185211. Schon, D.A. (1983) The Reective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. London, Temple Smith. Schumpeter, J.A. (1962) The Theory of Economic Development. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA. Spender, J.C. (1996) Making knowledge the basis of a dynamic theory of the rm. Strategic Management Journal 17(S2), 4562. Sull, D. (1999) Why good companies go bad. Harvard Business Review Jul-Aug, 4252. Whyte, W.F. (1956) Organization Man. New York, Simon & Schuster.

LYNDA GRATTON, London Business School, Sussex Place, Regents Park, London NW1 4SA, UK. Email: lgratton@london.edu Lynda Gratton is Associate Professor of Organizational Behaviour at London Business School. She is Director of the Leading Edge Research Consortium and heads the Executive Programme, Human Resource Strategy in Transforming Organizations. Her research interests focus on strategic HRM and business alignment. A recent book is Living Strategy: Putting People at the Heart of Corporate Purpose (FT Prentice-Hall, 2001).

SUMANTRA GHOSHAL, London Business School, Sussex Place, Regents Park, London NW1 4SA, UK. E-mail: sghoshal@london.edu Sumantra Ghoshal is Professor of Strategic and International Business Management at London Business School, Founding Dean of the Indian School of Business, Hyderabad, and Member of the Committee of Overseers of Harvard Business School. A prolic and award-winning author, his reasearch centres on strategic, organizational and managerial issues confronting large, global companies. His most recent, award-winning book is Managing Radical Change.

10

European Management Journal Vol. 21, No. 1, pp. 110, February 2003

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Standard Calibration Procedure Thermocouple Doc. No. Call/SCP/024 Rev. 00 May 01, 2015Document4 pagesStandard Calibration Procedure Thermocouple Doc. No. Call/SCP/024 Rev. 00 May 01, 2015Ajlan KhanNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- WBI06 01 Rms 20190124Document17 pagesWBI06 01 Rms 20190124Imran MushtaqNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- A Multi-Objective Model For Fire Station Location Under UncertaintyDocument8 pagesA Multi-Objective Model For Fire Station Location Under UncertaintyAbed SolimanNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Scheduling BODS Jobs Sequentially and ConditionDocument10 pagesScheduling BODS Jobs Sequentially and ConditionwicvalNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Newsletter April.Document4 pagesNewsletter April.J_Hevicon4246No ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Sfnhs Form 138 & 137 No LinkDocument9 pagesSfnhs Form 138 & 137 No LinkZaldy TabugocaNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- SplunkCloud-6 6 3-SearchTutorial PDFDocument103 pagesSplunkCloud-6 6 3-SearchTutorial PDFanonymous_9888No ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Solution To Information TheoryDocument164 pagesSolution To Information Theorynbj_133% (3)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Test Bank For Environmental Science For A Changing World Canadian 1St Edition by Branfireun Karr Interlandi Houtman Full Chapter PDFDocument36 pagesTest Bank For Environmental Science For A Changing World Canadian 1St Edition by Branfireun Karr Interlandi Houtman Full Chapter PDFelizabeth.martin408100% (16)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- Affine CipherDocument3 pagesAffine CipheramitpandaNo ratings yet

- Lighthouse Case Study Solution GuideDocument17 pagesLighthouse Case Study Solution Guidescon driumNo ratings yet

- Shriya Arora: Educational QualificationsDocument2 pagesShriya Arora: Educational QualificationsInderpreet singhNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- 1634858239Document360 pages1634858239iki292100% (1)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- District Plan of ActivitiesDocument8 pagesDistrict Plan of ActivitiesBrian Jessen DignosNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Pagdaragdag (Adding) NG Bilang Na May 2-3 Digit Na Bilang Na May Multiples NG Sandaanan Antas 1Document5 pagesPagdaragdag (Adding) NG Bilang Na May 2-3 Digit Na Bilang Na May Multiples NG Sandaanan Antas 1Teresita Andaleon TolentinoNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- 2 Reason Why I Like DoraemonDocument2 pages2 Reason Why I Like Doraemonpriyanka shafiraNo ratings yet

- Digital Citizenship RubricDocument1 pageDigital Citizenship Rubricapi-300964436No ratings yet

- Curriculum Evaluation ModelsDocument2 pagesCurriculum Evaluation ModelsIrem biçerNo ratings yet

- LoyalDocument20 pagesLoyalSteng LiNo ratings yet

- Manuel Quezon's First Inaugural AddressDocument3 pagesManuel Quezon's First Inaugural AddressFrancis PasionNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Impact of Social Media in Tourism MarketingDocument16 pagesImpact of Social Media in Tourism MarketingvidhyabalajiNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Tusculum College Catalog 2011-2012Document187 pagesTusculum College Catalog 2011-2012Tusculum CollegeNo ratings yet

- JCL RefresherDocument50 pagesJCL RefresherCosta48100% (1)

- 015-Using Tables in ANSYSDocument4 pages015-Using Tables in ANSYSmerlin1112255No ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Lesson Exemplar On Contextualizing Science Lesson Across The Curriculum in Culture-Based Teaching Lubang Elementary School Science 6Document3 pagesLesson Exemplar On Contextualizing Science Lesson Across The Curriculum in Culture-Based Teaching Lubang Elementary School Science 6Leslie SolayaoNo ratings yet

- Mental Fascination TranslatedDocument47 pagesMental Fascination Translatedabhihemu0% (1)

- Blueprint 7 Student Book Teachers GuideDocument128 pagesBlueprint 7 Student Book Teachers GuideYo Rk87% (38)

- HTTP API - SMS Help GuideDocument8 pagesHTTP API - SMS Help Guideaksh11inNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Differential Aptitude TestsDocument2 pagesDifferential Aptitude Testsiqrarifat50% (4)

- Jesd51 13Document14 pagesJesd51 13truva_kissNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)