Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Aero Tropo List

Uploaded by

Basuki Rahardjo0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

19 views13 pagesAirports have increasingly developed non-aeronautical commercial Iacilities and services. Retail sales per square meter average three to Iour times greater than shopping malls. Airports are developing their landside areas with hotels, oIice and retail complexes, conIerence and exhibition centers.

Original Description:

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentAirports have increasingly developed non-aeronautical commercial Iacilities and services. Retail sales per square meter average three to Iour times greater than shopping malls. Airports are developing their landside areas with hotels, oIice and retail complexes, conIerence and exhibition centers.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

19 views13 pagesAero Tropo List

Uploaded by

Basuki RahardjoAirports have increasingly developed non-aeronautical commercial Iacilities and services. Retail sales per square meter average three to Iour times greater than shopping malls. Airports are developing their landside areas with hotels, oIice and retail complexes, conIerence and exhibition centers.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 13

1

1uly 26, 2006

Airport Cities and the Aerotropolis

Dr. 1ohn D. Kasarda

Airports have historically been understood as places where aircraIt operate, including the

runways, control towers, terminals, hangers and other Iacilities which directly serve aircraIt,

passengers and cargo. This historical understanding is giving way to a broader, more

encompassing concept which recognizes the Iact that in addition to their core aeronautical

inIrastructure and services, virtually all major airports have increasingly developed non-

aeronautical commercial Iacilities and services.

No longer restricted to magazine shops and Iast Iood outlets, passenger terminals now

Ieature brand name boutiques, specialty retail, and upscale restaurants along with entertainment

and cultural attractions. Singapore Changi, Ior instance, has cinemas; Beijing Capital Airport,

banks; Hong Kong International, dozens oI designer clothing shops; Las Vegas McCarran, a

museum; Fraport, a hospital; Amsterdam Schiphol, a Dutch Masters art gallery; and Stockholm

Arlanda, an intensively utilized chapel where over 400 weddings occurred in 2005.

Given the signiIicantly higher incomes oI airline passengers (typically three to Iive times

higher than national averages) and the huge volumes oI passengers Ilowing through the terminals

(oIten in the tens oI millions annually) it is not surprising that retail sales per square meter

average three to Iour times greater than shopping malls and downtown shops. As a result,

terminal commercial lease rates tend to be the highest in the metropolitan area.

2

In additional to incorporating a variety oI commercial Iunctions into passenger terminals,

airports are developing their landside areas with hotels, oIIice and retail complexes, conIerence

and exhibition centers, logistics and Iree trade zones, and time-sensitive goods processing

Iacilities. Consequently, many airports today receive greater percentages oI their revenues Irom

non-aeronautical sources than Irom acronautical sources (e.g., landing Iees, gate leases,

passenger service charges). These non-acronautical revenues have become critical to airports

meeting their Iacility modernization and inIrastructure expansion needs, as well as being cost-

competitive in attracting and retaining airlines.

The growth oI non-aeronautical activities at airports not only Iavorably impacts their

Iinances. Airport-centric commercial development is also making them leading urban growth

generators as they become signiIicant employment, shopping, trading, business meeting and

leisure destinations in their own right. The evolution oI these non-aeronautical Iunctions and

commercial land uses has transIormed numerous city airports into airport cities.

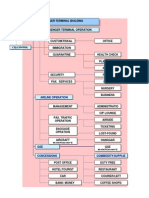

The New Airport Management Model

Consistent with their growing non-aeronautical roles and Iunctions, airports are altering

their operational management. Numerous airports (both public and private sector operated) have

established real estate or property divisions to develop their landside commercial areas as well as

Ioster development beyond airport boundaries (e.g., British Airports Authority, Aeroports de

Paris, Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport, FrankIurt Airport |Fraport|, Amsterdam Schiphol,

Singapore Changi). These new operational structures oIIer testimony that airports are evolving

3

Irom basic aeronautical inIrastructures into complex multiIunctional enterprises serving both

aeronautical needs and commercial development. The current trend in airport management is

thereIore to complement traditional technical airport Iunctions with terminal and landside

commercial activities. Such activities include, among others;

duty Iree shops

restaurants and specialty retail

cultural attractions

hotels and accommodation

business oIIice complexes

convention and exhibition centers

leisure, recreation, and Iitness

logistics and distribution

light manuIacturing and assembly

perishables and cold storage

catering and other Iood services

Free Trade Zones and Customs Free Zones

gold courses

Iactory outlet stores

personal and Iamily services such as health and child daycare

To many not Iamiliar with the new realities oI airports, the Airport City model might

appear to be a deviation Irom the norm. But it is in Iact becoming the new model oI international

4

airport development and management. Airports Irom Amsterdam to Zurich and Irom Beijing to

Seoul have embraced this planning model to develop their terminals and landside areas as a

pivotal means to Iinancing airport operations and contributing to their own competitiveness. To

note just a handIul:

Beijing is rapidly proceeding with its highly ambitious Capital Airport City, whose

master plan takes an expansive deIinition oI appropriate Iunctions including, among

others, shopping, entertainment, education, sports and leisure, light manuIacturing,

Iinance, trade, and housing.

Aeroports de Paris established a real estate division in 2003 to act as the developer,

general contractor and construction project owner and manager oI landside commercial

properties at Charles de Gualle and Orly International Airports.

Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport management has been in the real estate

development business Ior three decades, leasing land to commercial tenants.

Hong Kong International Airport`s SkyCity is opening a 1 million square meter retail,

exhibition, business oIIice, hotel and entertainment complex near its passenger terminal.

The Iirst major phase will be in Iull operation by the end oI 2006.

Kuala Lumpur`s (KLIA) new Airport City will be commercially anchored by its large

Gateway Park that, in addition to retail and oIIice development, includes motor sports, an

automobile hypermarket, and leisure venues drawing on the local as well as aviation-

induced market.

Incheon`s 'Winged City encompasses international business areas, logistics zones,

shopping and tourism districts, as well as housing and services (e.g., medical) Ior Airport

City workers and residents.

5

The new Bangkok International Airport (Suvarnabhumi) is expected to open in late 2006.

Its master plan includes the development oI an Airport City within airport boundaries to

include an international business center, international conIerence and exhibition center, a

shopping center, oIIice buildings, hotels, car-parks, hospitals, restaurants, an

entertainment center, and an international resident community.

Amsterdam Schiphol, through its Schiphol Real Estate Group, has been involved Ior well

over a decade in landside commercial development. These developments include

business oIIice complexes, hotels, meeting and entertainment Iacilities, logistics parks,

shopping, and other commercial activities branded under the AirportCity name. Nearly

58,000 people are employed at Schiphol, which integrates multimodal transportation,

regional corporate headquarter oIIices, retail shopping, logistics, and exhibition space to

Iorm a major economic growth pole Ior the Dutch economy.

Other international airports, not quite the scale oI Amsterdam Schiphol or Seoul`s

Incheon have given commercial development a high priority in their master planning (e.g.,

Brisbane Airport, Vienna, Canada`s Calgary, Zurich, and Stockholms Arlanda Airport). The

majority oI these have embraced the Airport City concept in their strategic development models,

either explicitly or implicitly.

As a result, airports are undergoing a metamorphosis, taking on many oI the commercial

Iunctions oI a metropolitan Central Business District (CBD). With the growing number oI

boutiques, restaurants, meeting Iacilities, and entertainment and cultural attractions, passenger

terminals resemble parts oI downtown. Many airports also have the density oI highway and rail

6

connections that are usually associated with CBDs. This is reinIorcing their new roles as drivers

oI business location and urban development over an extended area.

The Rise of The Aerotropolis

Even greater aviation-oriented commercial development is occurring well beyond airport

boundaries. With the airport itselI serving as a region-wide multimodal transportation and

commercial nexus, strings and clusters oI airport-linked business parks, inIormation and

communications technology complexes, retail, hotel and entertainment centers, industrial parks,

logistics parks, wholesale merchandise marts and residential developments are Iorming along

airport arteries up to 20 kilometers outward.

This more dispersed airport-linked development is giving rise to a new urban-Iormthe

Aerotropolis. Similar in shape to the traditional metropolis, made up oI a central city and its

commuter-linked suburbs, the Aerotropolis consists oI an airport city core and extensive outlying

areas oI aviation-oriented businesses and their associated residential developments. A

synthesized model oI the Aerotropolis based on development Ieatures around major international

hub airports is illustrated in Figure 1.

7

ReIlecting the new economy`s demands Ior connectivity, speed and agility, the

Aerotropolis is optimized by corridor and cluster development, wide lanes, and Iast movements.

In other words, Iorm Iollows Iunction. Airport expressway links (aerolanes) complemented by

airport express trains (aerotrains) bring cars, taxis, buses, trucks and rail together with air

inIrastructure at the multimodal commercial core (the airport city). Aviation-linked business

8

clusters and associated residential developments radiate outward Irom the airport city, Iorming

the greater Aerotropolis.

Aerotropolises are emerging because oI the advantages airports provide to business in the

Iast-paced, globally networked economy. Today`s most competitive manuIacturers, Ior example,

use advanced inIormation technology and high-speed transportation to provide Iast and Ilexible

responses to customers` unique needs. Such Iirms build agile production systems that connect

them to their suppliers and customers, allowing them to source parts and ship assembled

products as needed.

A manuIacturer`s ability to meet customer demand also depends on the existence oI a

comprehensive ground-to-air shipping network oI air cargo carriers, trucking companies, Ireight

Iorwarders, and logistics providers. This network has been strengthened as demand Ior time-

sensitive manuIacturing and distribution grows. Made possible primarily by proximity to an

airport, a ground-to-air shipping network allows manuIacturers to minimize their inventories,

shorten production-cycle times, and quickly access novel inputs Ior custom products that create

additional value.

Like time-sensitive goods processing industries, the service sector has increasingly Iound

airport areas to be an attractive location. Airports have become magnets Ior regional corporate

headquarters, conIerence centers, trade representative oIIices, and inIormation-intensive Iirms

that require executives and staII to undertake Irequent long-distance travel. Business travelers

beneIit considerably Irom quick access to hub airports, which oIIer greater choice oI Ilights and

9

destinations and more Ilexibility in rescheduling as well as oIten avoiding the costs oI overnight

stays.

Firms specializing in inIormation and communications technology and other high-tech

industries consider air accessibility especially crucial. High-tech proIessionals travel by air at

least 60 percent more Irequently than other proIessionals, giving rise to the term 'nerd birds in

the U.S. Ior commercial aircraIt connecting 'techie capitals such as Austin, Boston, Raleigh-

Durham, and San Jose. Many high tech Iirms are locating along major airport corridors, such as

those along the Washington Dulles Airport access corridor in Northern Virginia and the

expressways leading to Chicago`s O`Hare International Airport. In this sense, knowledge

networks and air travel networks increasingly reinIorce each other.

Lastly, commercial services oI all types have begun relocating to airport areas in order to

attract a dual customer base oI travelers and locals. Airports now oIIer on-site or nearby hotels,

restaurants, shopping, Iitness centers, and entertainment Iacilities. As these oIIerings grow, areas

within Iive kilometers oI major airports are adding jobs considerably Iaster than suburbs located

at similar distances Irom a metropolis` center, but not near an airport. Such job growth

stimulates residential projectsIurther Iueling Aerotropolis development. Airport areas are

even developing their own 'brand image'the DFW Area . 'the O`Hare Area. Ior

instance.

In sum, by oIIering speedy distant market connectivity to aerotropolis businesses, the

airport provides important value to these businesses. Aerotropolis businesses, in turn, generate

10

additional passengers and cargo Ior the airports, resulting in reciprocal beneIits. Figure 2

illustrates these reciprocal beneIits Ior Amsterdam Schiphol`s Airport City and its greater

Aerotropolis.

Although airport cities initially evolved in Western countries the broader Aerotropolis is

emerging most vividly around Asia`s newer international gateway airports. This can be seen in

developments at and near Hong Kong International Airport, South Korea`s Incheon, Beijing

Capital International Airport, and as planned around Bangkok`s new international airport,

Suvarnabhumi.

11

The Future Aerotropolis

To serve the economic demands oI connectivity, speed, and agility, the Aerotropolis will

require localized inIrastructure planning oI unprecedented scale. To date, most Aerotropolises

have evolved largely spontaneously, with existing nearby development oIten creating arterial

bottlenecks. In the Iuture, strategic inIrastructure planning could reduce this congestion.

Dedicated expressway links (aerolanes) and high-speed rail (aerotrains) should eIIiciently

connect airports to business and residential clusters near and Iar. Special truck-only lanes should

be added to airport expressways, as should improved highway interchanges to reduce congestion.

Multimedia technologies should produce themed electronic public art along airport transportation

corridors that highlight the culture, history and economic assets oI the region the airport serves.

Global inIormation and communications technology (ICT) networks will also help shape

the Aerotropolis. Advanced inIormation processing technologies and multimedia

telecommunications systems served by high-density Iiber-optic rings and satellite uplinks and

downlinks will evolve around airports, instantly connecting companies to their global suppliers,

distributors, customers, and branch oIIices and partners. Companies that require the Iastest

possible networking will thus have an additional reason to locate in the Aerotropolis. This ICT

inIrastructure is appearing not only around major passenger airports like Incheon and

Washington Dulles but also around U.S. air express hubs such as Memphis (which serves global

shipper FedEx) and Louisville (which serves United Parcel Service).

As multimodal transportation and advanced communications inIrastructure develops at

and near airports, businesses will have even more reason to move to an Aerotropolis. The

12

principal determinant oI land value, lease rates, and the type oI commercial use on a given

property will be the cost oI moving people and products to and Irom the airport and, via the

airport, to distant markets. This value/cost proposition will be measured primarily in time to the

airporta Iunction oI the site`s place on local transportation arteries, and not necessarily oI

spatial distance. For example, a site 10 kilometers away, but one stop on a high-speed train line,

Irom the airport will be worth more than a site 5 kilometers away with poor road and rail

connections. To put it another way, the three 'A`s (accessibility, accessibility, accessibility)

will become the critical component oI the three 'L`s (location, location, location) in

Aerotropolis real estate value.

At Iirst glance, one might misconstrue Aerotropolis land uses as simply additional sprawl

along main airport transportation corridors. In reality, the Aerotropolis grows according to a

rational system based on time-cost access gradients radiating outward Irom the airport.

Constructing appropriate multimodal ground transit and locating commercial Iacilities consistent

with the Iorm and Iunction oI the Aerotropolis will contribute substantially to the emerging

needs oI business, more eIIicient cargo and passenger Ilows, and the Iuture competitiveness oI

urban areas.

These outcomes will not occur spontaneously, however. Aerotropolis optimization will

require bringing together airport planning, urban planning, and business site planning in a

synergistic manner so that development is economically eIIicient, aesthetically pleasing and

environmentally sustainable.

13

Author Note: John D. Kasarda, PhD, is Kenan Distinguished ProIessor oI Management and

Director oI the Kenan Institute oI Private Enterprise at the University oI North Carolina`s Kenan-

Flagler Business School. He advises airports and government oIIicials around the world on

airport city and Aerotropolis development.

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- ZBAADocument91 pagesZBAAzacklaws100% (1)

- Airport Literature StudyDocument15 pagesAirport Literature StudySoundar Rajan100% (2)

- Airport Terminal BuildingDocument101 pagesAirport Terminal BuildingVishalTiwariNo ratings yet

- JO2058 - 2019-05-08-Bca-A320-Captain-Brief-2 - 18 Jul 2019Document3 pagesJO2058 - 2019-05-08-Bca-A320-Captain-Brief-2 - 18 Jul 2019gfernandezv0% (1)

- Airlines in Asia PacificDocument40 pagesAirlines in Asia PacificmeqalomanNo ratings yet

- Rekap Total ME Ngurah RaiDocument1 pageRekap Total ME Ngurah RaiBasuki Rahardjo100% (1)

- Toc Adrm 9 Ed 2004Document7 pagesToc Adrm 9 Ed 2004Basuki Rahardjo100% (1)

- Diagram Flow Penumpang & - BarangDocument4 pagesDiagram Flow Penumpang & - BarangBasuki RahardjoNo ratings yet

- S CurveDocument12 pagesS CurveBasuki RahardjoNo ratings yet

- Toc Adrm 9 Ed 2004Document7 pagesToc Adrm 9 Ed 2004Basuki Rahardjo100% (1)

- API NgurahRai Design&Build Undangan Beauty ContestDocument2 pagesAPI NgurahRai Design&Build Undangan Beauty ContestBasuki RahardjoNo ratings yet

- Civil: Nternational Aviation RganizationDocument1 pageCivil: Nternational Aviation RganizationBasuki RahardjoNo ratings yet

- AcnpcnDocument76 pagesAcnpcnBasuki RahardjoNo ratings yet

- Time Schedule DairiDocument8 pagesTime Schedule DairiBasuki RahardjoNo ratings yet

- CBR 6 % E 137.9 CM Phase II Rsi 84.87234 PCN 135.7957Document1 pageCBR 6 % E 137.9 CM Phase II Rsi 84.87234 PCN 135.7957Basuki RahardjoNo ratings yet

- Holiday Detector KV Check Report: Attachment 1Document1 pageHoliday Detector KV Check Report: Attachment 1Basuki RahardjoNo ratings yet

- Wind Speed / Direction N NE E SE S SW W NW Calm 1 - 2Document2 pagesWind Speed / Direction N NE E SE S SW W NW Calm 1 - 2Basuki RahardjoNo ratings yet

- Pekerjaan Terminal Dan Sarana Penunjang Di Bandar Udara Sepinggan BalikpapanDocument1 pagePekerjaan Terminal Dan Sarana Penunjang Di Bandar Udara Sepinggan BalikpapanBasuki RahardjoNo ratings yet

- 150 - 5345 - 42GSpecification For Airport LightDocument34 pages150 - 5345 - 42GSpecification For Airport LightBasuki RahardjoNo ratings yet

- Approach and Threshold LightingDocument1 pageApproach and Threshold LightingBasuki RahardjoNo ratings yet

- AFL-009 - Detail Apron Flood Light Layout1Document1 pageAFL-009 - Detail Apron Flood Light Layout1Basuki RahardjoNo ratings yet

- NAV-011 - System Diagram Layout1Document1 pageNAV-011 - System Diagram Layout1Basuki RahardjoNo ratings yet

- AFL-021 - General Principle of Afl Rcms Layout1Document1 pageAFL-021 - General Principle of Afl Rcms Layout1Basuki RahardjoNo ratings yet

- AFL-021 - General Principle of Afl Rcms Layout1Document1 pageAFL-021 - General Principle of Afl Rcms Layout1Basuki RahardjoNo ratings yet

- NAV-011 - System Diagram Layout1Document1 pageNAV-011 - System Diagram Layout1Basuki RahardjoNo ratings yet

- NAV-012 - VHF Receivers - Single Line Diagram Layout1Document1 pageNAV-012 - VHF Receivers - Single Line Diagram Layout1Basuki RahardjoNo ratings yet

- AFL-011 - Detail Spot Number Light Layout1Document1 pageAFL-011 - Detail Spot Number Light Layout1Basuki RahardjoNo ratings yet

- AFL-015 - Runway Edge Light Surface Type ModelDocument1 pageAFL-015 - Runway Edge Light Surface Type ModelBasuki RahardjoNo ratings yet

- AFL-021 - General Principle of Afl Rcms Layout1Document1 pageAFL-021 - General Principle of Afl Rcms Layout1Basuki RahardjoNo ratings yet

- AFL-009 - Detail Apron Flood Light Layout1Document1 pageAFL-009 - Detail Apron Flood Light Layout1Basuki RahardjoNo ratings yet

- AFL-010 - Wiring Diagram Apron Flood Light Layout1Document1 pageAFL-010 - Wiring Diagram Apron Flood Light Layout1Basuki RahardjoNo ratings yet

- AFL-010 - Wiring Diagram Apron Flood Light Layout1Document1 pageAFL-010 - Wiring Diagram Apron Flood Light Layout1Basuki RahardjoNo ratings yet

- AFL-020 - Rotating Beacon Layout1Document1 pageAFL-020 - Rotating Beacon Layout1Basuki RahardjoNo ratings yet

- NAV-013 - VHF Transmission - Single Line Diagram Layout1Document1 pageNAV-013 - VHF Transmission - Single Line Diagram Layout1Basuki RahardjoNo ratings yet

- 001 - Drawing List Building Architecture BintanDocument1 page001 - Drawing List Building Architecture BintanBasuki RahardjoNo ratings yet

- Kuala Lumpur - Beijing - Tianjin - Harbin 24th DECEMBER 2017 - 2nd JANUARY 2018Document61 pagesKuala Lumpur - Beijing - Tianjin - Harbin 24th DECEMBER 2017 - 2nd JANUARY 2018Fiffy Azza TandangNo ratings yet

- Wa0130.Document1 pageWa0130.Ahsan AliNo ratings yet

- ZBAA - Beijing-Capital Airport - SkyVectorDocument2 pagesZBAA - Beijing-Capital Airport - SkyVectorgfernandezvNo ratings yet

- Beijing Daxing International AirportDocument10 pagesBeijing Daxing International AirportСюэцин СяNo ratings yet

- MH370 (MAS370) Malaysia Airlines Flight Tracking and History 11-Mar-2014 (KUL - WMKK-PEK - ZBAA) - FlightAwareDocument2 pagesMH370 (MAS370) Malaysia Airlines Flight Tracking and History 11-Mar-2014 (KUL - WMKK-PEK - ZBAA) - FlightAware陳佩No ratings yet

- ZBAADocument68 pagesZBAAshilomusoso229No ratings yet

- Mice ChinaDocument64 pagesMice ChinaSTP DesignNo ratings yet

- 2018 Beijing Airport Annual ReportDocument171 pages2018 Beijing Airport Annual ReportJeffrey AuNo ratings yet

- MR Albertson ItineraryDocument3 pagesMR Albertson Itineraryapi-283060809No ratings yet

- PriorityPass Lounge DirectoryDocument231 pagesPriorityPass Lounge DirectoryCharan ReddyNo ratings yet

- PP New Lounge ListDocument48 pagesPP New Lounge ListUdit KaulNo ratings yet

- Potential Opportunities For Asian Airports To Develop Self-Connecting Passenger MarketsDocument10 pagesPotential Opportunities For Asian Airports To Develop Self-Connecting Passenger MarketsAnsgar SkauNo ratings yet

- Beijing Capital Intl Airport: China / Hong Kong Company GuideDocument13 pagesBeijing Capital Intl Airport: China / Hong Kong Company GuideJ. BangjakNo ratings yet

- 2017 Beijing Airport Annual ReportDocument159 pages2017 Beijing Airport Annual ReportJeffrey AuNo ratings yet

- Sustainability 12 05512Document14 pagesSustainability 12 05512Nemanja IvanovićNo ratings yet

- Terminal 3 Beijing - Kailiao PDFDocument21 pagesTerminal 3 Beijing - Kailiao PDFTeja BawanaNo ratings yet

- Transportation Research Part A: Qiong Zhang, Hangjun Yang, Qiang Wang, Anming ZhangDocument13 pagesTransportation Research Part A: Qiong Zhang, Hangjun Yang, Qiang Wang, Anming ZhangLi XiangNo ratings yet

- Bus Part A2P ReadingBank U1Document2 pagesBus Part A2P ReadingBank U1LolaNo ratings yet

- Air ChinaDocument8 pagesAir Chinabicko akokoNo ratings yet

- Top AirportsDocument2 pagesTop AirportsJakub SedlakNo ratings yet

- Travel Reservation August 20 For THNGDocument2 pagesTravel Reservation August 20 For THNGsithulibraNo ratings yet

- Airlines and Aircraft Update ReadmeDocument30 pagesAirlines and Aircraft Update Readmeclip215No ratings yet

- Boeing Current Market Outlook 2012 2031 PDFDocument43 pagesBoeing Current Market Outlook 2012 2031 PDFSani SanjayaNo ratings yet

- DP Lounge List Asia Pacific VIDocument1 pageDP Lounge List Asia Pacific VInikerNo ratings yet

- Find Any Example of A Real Project With A Real Project ManagerDocument2 pagesFind Any Example of A Real Project With A Real Project Manageralum jacobNo ratings yet