Professional Documents

Culture Documents

6126

Uploaded by

Glenn DomingoCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

6126

Uploaded by

Glenn DomingoCopyright:

Available Formats

EFFECTIVE LECTURE TECHNIQUES Barbara Scherokman, MD Kaiser Permanente Fairfax, VA Donna Waechter, Ph.D Bethesda, MD I. Introduction II.

Principles of Adult Learning III. Planning the Presentation IV. Organizing and Delivering the Presentation A. Introduction, Body, Conclusion B. Instructional Materials C. Learner Involvement D. Delivery Skills APPENDICES A. Lecture Organizer B. Selecting Visual Aids C. Handouts D. Effective Questioning E. Speaker Feedback Form. I. INTRODUCTION The materials compiled here focus on the use of the lecture or presentation format as a teaching method. The lecture format requires the teacher to be active and the learner to be relatively passive. It is a format which is well-suited for transmitting knowledge and facilitating comprehension, and can be particularly effective for dissemination of new information. When done well, the lecture/presentation makes a valuable contribution to the learning process. Our intent here is to provide you with information to assist you in improving your presentation skills according to recognized principles of effective lecturing and to be able to do so in an organized and efficient manner. II. PRINCIPLES OF ADULT LEARNING We begin this section by considering how adults learn. The purpose here is to familiarize you with the characteristics of the educational experience that the teacher can manipulate to maximize the usefulness of the experience for the learner. As a teacher, it is important that you know how information is best received and used by adults. The better you understand this, the better you are able to structure the educational experience in a manner that effectively communicates the information you are trying to impart and the goals you are trying to achieve. Please note that this discussion focuses only on characteristics that the teacher can manipulate. Certainly there are other relevant characteristics in the educational experience, such as the learner's educational level, prior learning experiences, and intelligence, but as a teacher, you cannot control these. As you consider what the teacher can and cannot control, you gain a better appreciation for your responsibilities as a teacher. You cannot make someone learn, but you can provide an educational experience that is maximally conducive to learning. Numerous authors have examined the conditions which facilitate the learning process for adults. These conditions can be summarized as follows: 1. The opportunity for adult learners to apply knowledge soon after it is learned facilitates mastery and retention. The application of knowledge may be accomplished in a wide variety of ways, depending on what has been learned. Small group discussions can be used to review a case history and practice problem-solving skills. Role-playing can be used to practice patient interviewing techniques. Simulated patients can be used to practice physical examination skills. Computer case simulations can be used to practice differential diagnosis. 2. The complexity of the material taught influences the interest level of adult learners. While it is obviously important to know facts, adults are more stimulated and challenged by learning on a higher

level. Theories, concepts, and principles tend to hold the adult learner's attention more effectively than definitions and lists. If the facts are readily available in print form, and they are easily understood, adult learners can master such information on their own. Time teaching may be best spent in application of facts, problem-solving, or developing treatment plans..3. Matching the pace of the learning experience with the rate at which the learner can follow the material maximizes the efficiency of information processing. If the teacher presents information faster than the learner can process it, the learner is "lost." If information is presented much slower than the learner can process, he/she is bored. In order to determine how quickly to present information, the teacher must consider certain characteristics of the learner, such as skill level and previous training/education. With one-to-one learning experiences, finding the "right" pace may not be difficult for the teacher. In group learning experiences, however, proper pacing becomes more of a challenge. This is especially true if the group represents great variance in terms of skill level and training. When teaching groups very diverse in skill, the teacher may find it necessary to pace material with the group average in mind. Additional reading and alternate learning experiences might be used to appropriately challenge or remediate learners falling outside the group average. 4. When adult learners understand the importance or relevancy of the material taught, their motivation to learn increases and retention is more likely. An effective way to begin a learning experience is to explain why you are teaching what you are teaching. How is this information useful for the learner? For example, how will it help the learner provide better patient care? By explaining the relevancy of the material, you have grabbed the learner's attention, and helped him/her determine where this information "fits" with previously learned material. 5. Adults can learn more rapidly when they receive timely feedback about their progress. Feedback from the teacher needs to be balanced - learners need to know what they have done well, not just what must be improved. Such balanced feedback reinforces learner strengths and helps the learner focus on improving areas of weakness. External feedback from the teacher also helps the learner develop an internal ability to assess his/her strengths and weaknesses. This is an important ability which guides effective independent learning. 6. Involving the adult learner in the educational process helps stimulate learner motivation and conveys a sense of learner responsibility in the process. As stated earlier, the teacher can provide a variety of educational experiences, but cannot make someone learn. The learner must recognize his/her responsibility for learning, actively seeking information, asking questions, and finding answers. The teacher can involve the learner in the educational process in a variety of ways, such as asking thought- provoking questions, "brainstorming" ideas, and helping the learner establish personal educational goals. In summary, we have considered six conditions which facilitate adult learning. By developing educational experiences which incorporate these conditions, the teacher creates a learning environment which best facilitates the acquisition of new knowledge and skills. REFERENCES 1. Bunnell, K.P., Editor. Continuing Medical Educators Handbook. Colorado Medical Society, 1980. 2. Ende, J. Feedback in Clinical Medical Education. Journal of American Medical Association, 250: 777-781, 1983. 3. Gagne, R.M. The Conditions of Learning. New York: Holt, Rinchart & Winston, 1977. 4. Svinicki, M. How to Pace Your Lecture. The Teaching Professor, 3(9): 1-2, 1989..III. PLANNING THE PRESENTATION You may think that the first step in developing your presentation begins when you decide what you want to say about your topic. However, planning for an effective presentation begins before you determine the content of your talk. What you say and how you say it should be determined by the availability of information, audience characteristics, time constraints, and the purpose of the presentation. By asking yourself a series of questions, you can determine the most efficient way to construct your presentation and the most effective way to deliver it. To illustrate this planning process, we have asked the following questions, and provided some commentary for your information. 1. How easily can the listener access information on the topic you will present? If the information is readily available to the listener (e.g., class syllabus, textbook), it is probably unnecessary to use

lecture or presentation time covering the same material. Why spend time presenting information that the listener can just as easily obtain through reading? The presentation should serve as a unique source of information for the listener, and can do this in two ways. First, it can provide data which the listener cannot access easily or at all (e.g., unpublished research or your personal clinical experiences). Such material can greatly enhance information sources already available to the listener. Second, the presentation can be used to summarize or synthesize a great deal of information in a concise manner. The listener may not have the time or expertise to consult multiple sources and extract information in this manner. 2. Who are the listeners? To determine the appropriate level of sophistication to use in presenting material, you must know certain characteristics of your listeners. For example, how old are they? What is their educational level? What is their current knowledge of the topic area? Are there other factors you must consider when presenting the topic, such as gender, socioeconomic status, and social values? It is very important to match the level of listener knowledge to the complexity of presentation content. This facilitates the listener's ability to understand the material you present and also maintains listener interest. 3. How much time has been allotted for your presentation? To determine the amount of information you can present, you must know the amount of time available for your presentation. Obviously you can present more detail and complexity in 50 minutes than 15 minutes. Presenting too much information in the time allotted makes the presentation rushed and difficult for the listener to follow. In addition, if there is to be a question and answer period, you must also account for this in developing your presentation. Typically, speaking at the rate of 100 to 120 words per minute allows listeners to take notes and follow your presentation. If you wish the listener to be able to retain information without taking notes, your speech rate must slow to 75 words or less per minute. To become sensitive to your rate of speech, read aloud into a tape recorder, timing yourself for a minute or two. Count the number of words you read per minute. By listening to your recording, you receive additional feedback as to how you sound at 75 words per minute versus 120 words per minute, etc..4. What is the listener supposed to learn from your presentation? Too often we begin to construct the content of our presentation by asking "What do I want to say about this topic?" However, to determine the content of your presentation, your question should focus on the listener, not you. Knowing what you want the listener to learn determines what you need to say in your presentation. What the listener is supposed to learn from your presentation is often referred to as the presentation objectives. It can be very helpful for you to write down objectives before constructing your presentation. Objectives should always be written in terms of what the listener should learn or be able to do at the end of your presentation. In this way they serve as a guide for organizing and developing presentation content, and can also be useful in deciding how to measure if you have been successful in imparting information. After you have asked yourself the above questions and found the necessary answers then you are ready to begin developing your presentation, as described in the following section on presentation organization and delivery skills. REFERENCES 1. Bligh, D. What's the Use of Lectures? New York: Penguin Books, 1972. 2. Krathwohl, D.R., Bloom, B.S., and Masia, B.B. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. Book 2: Affective Domain. New York: Longman, 1980. 3. Lowman, J. Mastering the Techniques of Teaching. San Francisco: Josey-Bass, 1984. 4. Whitman, N.A. Creative Medical Teaching. Salt Lake City, Utah: University of Utah School of Medicine, 1990. 5. Whitman, N.A. There Is No Gene for Good Teaching: A Handbook on Lecturing for Medical Teachers. Salt Lake City, Utah: University of Utah School of Medicine, 1982. IV. ORGANIZING AND DELIVERING THE PRESENTATION An effective lecturer must present concepts in an organized manner and the delivery must hold the learners' attention. It is crucial that the topic be introduced appropriately, basic concepts are presented in a coherent and enthusiastic manner, important information is emphasized, the audience

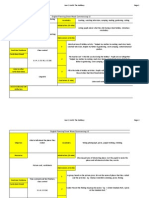

is actively involved, and there is a proper conclusion. To help you structure your lecture in a logical manner, a LECTURE ORGANIZER is included in Appendix A. This form contains prompts that help you remember the important components of a lecture. It can be xeroxed and filled out for each lecture you have to create. Before you actually sit down to put your lecture together you must first spend time on a general OVERVIEW of your talk. First you need to determine the basic purpose of your lecture. Next it is helpful to determine the three to five main points you want to make during your lecture. These main points will later be used in the body of the talk. Above all it is important to know the background of your audience. This helps you decide whether the material you present should be basic or more detailed and on a higher level.. A. INTRODUCTION, BODY & CONCLUSION Two of the most important parts to a lecture are the introduction and conclusion, however, these two components are usually given far too little attention. A good INTRODUCTION (Table 1) serves to get the listener on your side. It can be thought of as a way of shaking hands with the audience. The first thing that should be done in the introduction is to gain the listener's attention. For example, you may present a startling statistic, ask for a show of hands on an issue or start with something humorous. There is nothing wrong with being dramatic as long as you have content. Once attention is gained then you should establish the relevance of what you are going to say. Tell the audience how they will use the information in the future. At this point the goals of the lecture should be identified. One helpful way to do this is to say "at the end of this lecture you should be able to answer the following questions". Next the structure of the lecture can be discussed and it is often helpful to have the structure detailed on a slide, transparency or on a handout. This will give the listener a roadmap to follow during the talk. Finally, the ground rules can be established, such as, whether the audience should ask questions anytime or hold questions until the end. The BODY of the talk is an amplification of the three to five main concepts that you want to get across. The object of a lecture is not just to "get through" the material as fast as you can. The goal is to have the listener learn. If you attempt to cover too much, your audience will actually learn and remember less. Numerous studies show that students who listen to low density lectures actually score higher on tests than those who listen to high density talks. Therefore, the audience will learn more when they are given fewer concepts that are explained well. Lectures are the worst way to deliver a multitude of facts (use handouts for this purpose), but, they are the best way to transmit concepts. You should try to synthesize the information from various sources, add your own experience and present a series of basic concepts. Each of the three to five main concepts in the BODY (Table 2) of the talk should contain five essential parts. First the main concept should be stated in simple terms and then examples and exceptions should be given. Then the main concept should be restated. This can be done by using a phrase like "let me review what I've just told you". Make sure you highlight and emphasize important points. A transition should then be made to the next main concept with a short pause to give the listener time to think. Each of the five points of a single concept should take about five to seven minutes to go through. Table 1: INTRODUCTION Gain attention Establish relevance Identify goals State structure Establish ground rules.The information in the CONCLUSION (table 3) is an extremely important part of a presentation because it is what the audience is most likely to remember after they leave the room. The three to five main points should be summarized and if you told the audience in the introduction that they should be able to answer certain questions, you can ask these questions here. Next you should encourage questions from the audience. If the audience does not ask any questions then you may want to tell them about frequently asked questions from previous times when you have given the lecture. Finally, you should create some anticipation by briefly discussing a related lecture that you plan to give in the future.

After about 15 minutes learner attention falls dramatically. Any change in the speaker or the learner will increase attention and thus increase learning. Therefore, the speaker should change the format of the presentation every 15 minutes. Two major ways to increase attention are the use of INSTRUCTIONAL MATERIALS and LEARNER INVOLVEMENT. These techniques will be discussed in the following two sections. Table 2: BODY State main point in simple terms Give examples Give exceptions Restate main point Make a transition Table 3: CONCLUSION Summarize main points Ask key questions Encourage questions Create anticipation. B. INSTRUCTIONAL MATERIALS The term instructional materials (Table 4) refers to any visual or auditory material that is used in a lecture to assist the speaker in imparting information to the audience. The use of any instructional material must be planned and the content organized if it is to be truly supportive of the presentation. Since people tend to remember more of what they see and hear, as opposed to what they see or hear, visual aids are an important part of every effective presentation. When used skillfully, visual aids can clarify and reinforce the major focus of what is being presented. Do not use visual aids just for the sake of having them; visuals should enhance the listening process, not detract from what you have to say. There are different advantages and disadvantages (Appendix B) to each individual visual aid, so, you should select the type of visual aid with care. Visual aids should be simple and easy to understand. They should be used to convey only one concept. Do not apologize to the audience for bad visual aids; just don't use them. You should not incorporate too many words, numbers, and figures into the visual aid. Letters and numbers must be large enough to be read. As a general rule when using slides, use no more than seven words per line and no more than seven lines per slide. If the slide is clearly readable without magnification when held up to the light it should be easily read by the audience when projected. It is also important to use a good set of contrasting colors such as yellow on blue. To make sure your visual aids are readable you should go to the lecture hall, project your visual aids and see if you can read them from the back of the room. Visual aids should be well timed. If you use a prop or a model, once you are finished with it remove it from view. If it is still in view once you have gone onto a new concept, the audience will be distracted. Do not use visual material from other presentations which contain additional information which is not a part of your current presentation. It is important to remember that the speaker is always at the mercy of electronic devices that can malfunction at anytime. It is useful to carry a spare slide or overhead projector bulb as well as an extension cord. You should learn how to dislodge a slide that becomes jammed in the slide projector. Also, be sure to rearrange the room or position the visuals to enable everyone to see. Table 4: INSTRUCTIONAL MATERIALS Slides Photographs Videotapes Audiotapes Transparencies Models Blackboards Flip charts.Auditory aids such as audiotapes and videotapes are dramatic ways to convey a concept and often gain and keep the attention of the audience much more readily than a simple slide or transparency. It is the responsibility of the speaker to ensure that auditory aids can be easily heard by all present.

Again, auditory aids should only be introduced when relevant to the topic being presented. C. LEARNER INVOLVEMENT The audience learns more when they are involved in the presentation, and less when they are simply passive listeners. If the speaker incorporates activity, participation, and response into the structure of the presentation, the audience can learn more. There are a number of ways to involve the learner (Table 5). Any activity required, of course, should be relevant to the objectives of the presentation. Handouts (Appendix C) are a way to communicate the structure of your lecture and note-taking should be encouraged to facilitate learner activity. Questioning (Appendix D) the audience is particularly helpful and not only keeps the learners attention focused on the speaker, but, also lets the speaker know where the audience is in terms of knowledge base and understanding of the presentation. Table 5: WAYS TO INVOLVE LEARNERS STRATEGY DESCRIPTION 1. Questioning Either fact-based or problem-solving. 2. Case studies Description of a real or hypothetical situation for student analysis and problem resolution. 3. Patient simulations Patient presentation acted out by teacher or student with the patient information. Other students ask questions (with explanation of why they asked the question) to make the diagnosis. 4. Lecture handouts Brief outline of lecture to guide student note-taking. 5. Self Tests Written non-graded self tests 6. Brainstorming Soliciting student contributions on a certain topic (e.g. differential diagnosis) that are written on a board or flip chart. 7. Problem-posting Soliciting student questions or problems at beginning of lecture. Written on a board or flip chart, these student contributions clarify for the lecturer the students perceptions..The atmosphere you create during your presentation should be comfortable and non-threatening. People tend to be more confident in taking on challenges in the listening situation when they believe the presenter cares about their understanding. Certain types of statements and questions convey the message that the speaker is interested in ensuring that concepts have been clearly conveyed to the audience. Examples of such statements and questions are "please ask questions if something isn't clear," "That is a very good question. Let me explain this another way," "Some of you look puzzled. Do you have questions?" or "Are there any points which need clarification?" D. DELIVERY SKILLS Learning depends on what you say and how you say it. An effective presentation not only has content that is organized but also is communicated in a way that increases attention and interest. The speaker communicates with the listener by means of verbal and nonverbal channels. You are actually the performer and the medium. Numerous studies show that as much as 95% of communication is nonverbal. It is of utmost importance that you maintain good eye contact with the audience since eye contact is the main persuasive factor in a presentation. Each person should feel that you looked at them during your presentation. It is not good enough to look over the listeners heads as you gaze around the room. You should look at one person directly in the eyes for a few seconds then move on to another person. You can also get clues about whether the listeners are paying attention to what you are saying. Making eye contact with listeners also increases the likelihood that they will feel comfortable asking questions. Another important nonverbal technique is to project enthusiasm about your subject. You should transmit excitement to the audience. One way to transmit energy is to move more, however, it is important to gesture purposefully when you move. Do not pace up and down the floor, play with your pen or swing your arms aimlessly. These movements will detract from your message. You

should always gesture for a reason and your nonverbal behavior must be consistent with the content of your message. Content can be enhanced, distorted, or minimized by the effectiveness of your verbal communication. Your speech should always be clear and distinct so that you can be easily understood. Use a conversational manner of speaking and never read your lecture. Make sure that your voice is appropriately loud for the size of the room. You can vary the volume, pitch and rate of your speaking to place emphasis on important information and keep the audience alert. Avoid a monotonous style. It is important to remember that the way you use volume, pitch and rate should match the meaning and mood of the message you wish to convey. You should avoid verbal fillers such as "ugh" or "you know". There is nothing wrong with silence and it will give the audience a chance to think about and absorb what you are saying. Silence is a very effective attention getter. After you have finished preparing your lecture it is important to practice the presentation. Effective speaking skills can be learned and one of the most helpful ways is to videotape yourself or have a colleague give you feedback on your presentation. A speaker feedback form has been included as Appendix E. This form can be xeroxed and used for improving your presentation skills. REFERENCES LECTURE ORGANIZATION 1. Canlan J., Barabas A., Speaking at Medical Meetings: A Practical Guide. (2nd ed.): William Heinemann Medical Books Limited, 1981. 2. Cox K.R., Ewan C.E. (Eds.). The Medical Teacher. 2nd Ed.,New York: Churchill Livingston, 1987. 3. Foley R.P., Smilansdy J., Teaching Techniques: A Handbook for Health Professionals. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1980. 4. How to Pace Your Lectures. The Teaching Professor 3(9):1-2,1989. 5. Improving Lectures. Idea Paper No. 14. Center for Faculty Evaluation and Development. Kansas State University. September, 1985. 6. Kroenke K., The Lecture: Where it Wavers. JAMA 77:393- 396,1984. 7. Lecturing Tips for Large Classes. The Teaching Professor 2(4):4-5,1988. 8. McGee R. (Ed.). Teaching the Mass Class. Washington, DC: American Sociological Association, 1986. 9. McKeachie W.J., Teaching Tips: A guidebook for the beginning college teacher. (8th ed.) Lexington, Mass: C.C. Heath, 1986. 10. Naftulin D.H., Ware J.E., Donnelly F.A., The doctor fox lecture: a paradign of educational seduction. J Med Ed 48:630-635,1973. 11. Neff R.A., Weimer M. (Eds.). Classroom Communication: Collected Readings for Effective Discussions and Questioning. Madison WI: Magna Publications, Inc., 1989. 12. Newble D., Cannon R., A Handbook for Medical Teachers. (2nd ed.): MTP Press, Boston, Mass, 1987. 13. Organization: Communicating the Structure. The Teaching Professor 2(9):1-3,1988. 14. Russell I.J., Hendricson W.D., Herbert R.J., Effects of lecture information density on medical student achievement. J Med Ed 59:881-889,1984. 15. Schwenk T.L., Whitman N.A., The Physician as Teacher. Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, Maryland, 1987. 16. Weimer M.G. (Ed.). Teaching Large Classes Well. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, no.32. San Francisco: Jossey Bass, 1987. VISUAL AIDS 1. Richardson G.T., Illustrations. Humana Press, Clifton, NJ, 1985. 2. Robertson B., How to Draw Charts & Diagrams. Northern Light Books. Cincinnati, Ohio, 1988. 3. Tufte E.R., Envisioning Information. Graphics Press, Cheshire, Connecticut, 1990. 4. Tufte E.R., The Visual Display of Quantitative Information. Graphics Press, Cheshire, Connecticut, 1988. 5. White J.V., Graphic Idea Notebook. Watson-Guptill Pub.: New York, 1980, p 192. 6. Wileman R.E., Exercises in Visual Thinking. Hastings House Pub.: New York, 1980, p 124. 7. Zelazny G., Say it with Charts. Dow Jones-Irwin, Homewood, Illinois, 1985..

LEARNER INVOLVEMENT 1. Cashin W.E., McKnight P.C., Improving Discussions (IDEA Paper No. 15). Manhattan, K.S.: Kansas State University, Center for Faculty Evaluation and Development, 1986. 2. Frederick P.J., The Lively Lecture - 8 variations. CollegeTeaching 34(2):43-50,1986. 3. Gleason M., An instructor survival kit: For use with large classes. In RA Neff & M Weimer (Eds.). Teaching College: Collected Readings for the New Instructor (pp. 75-80). Madison, W.I.: Magna Publications, Inc, 1990. 4. Neff R.A., Weimer M. (Eds.). Classroom Communication: Collected Readings for Effective Discussion and Questioning. Madison, W.I.: Magna Publications, Inc., 1989. 5. Questions: Making Learners Think. The Teaching Professor 2(5),1988. 6. Russell I.J., Caris T.N., Harris G.D., Hendricson W.D., Effects of three types of lecture notes on medical student achievement. J Med Ed 8:627-636,1983..APPENDICES A. Lecture Organizer B. Selecting Visual Aids C. Handouts D. Effective Questioning E. Speaker Feedback Form. Appendix A LECTURE ORGANIZER TITLE _________________________________________________________________________ DATE ___________________ AUDIENCE ________________________________________________ I. OVERVIEW: A. What is the purpose of your lecture? B. What are 3-5 main points you want to make in your lecture? C. What is the background of your audience?. II. INTRODUCTION: A. How will you gain their attention? B. How will you establish relevance to the learner? C. What are the goals of your lecture? D. What is the structure of your lecture? E. What ground rules will you establish?. III. BODY: 3-5 main points, for each: - state main point in simple terms - give examples or illustrations - give major exceptions - restate main point in different words - make a transition to next main point. IV. CONCLUSION: A. How will you summarize the main points? B. What questions will you ask learners? C. How will you encourage learners to ask questions? D. How will you create some anticipation for future presentations?. V. VISUAL AIDS: A. What main points or concepts could be made more understandable by a visual aid? B. What types of visual aids could you use to illustrate the above main points or concepts? C. Sketch your visual aids in the space provided VI. LEARNER INVOLVEMENT: A. Write at least 5 fact-based questions to include in the body of your lecture.

B. Write 1-2 problem-solving questions or case studies to include in the body or conclusion of your lecture. C. Describe two strategies (other than questioning) you can use during your lecture to involve learners..Appendix B SELECTING VISUAL AIDS I. WHY ARE VISUAL AIDS IMPORTANT? A. Visual Aids... 1. make the presentation more interesting 2. make the presentation easier to follow 3. transfers ideas rapidly 4. help keep you organized 5. increase student retention II. ADVANTAGES & DISADVANTAGES OF VARIOUS VISUAL AIDS A. Slides 1. Advantages a. Suitable for large audiences b. Adds interest to your presentation c. Easy to store and carry d. Sequence of slides easily rearranged e. Can simplify complex ideas or data f. Helps you stay organized 2. Disadvantages a. Requires at least partial darkness for viewing b. Requires projection equipment, screen & electrical outlet c. Can get out-of-sequence or projected incorrectly d. Equipment takes time to set-up e. Equipment can malfunction or fail 3. When to use slides a. When the audience will not be taking notes b. When the room can be darkened substantially c. When attention on the presenter is not important d. To simplify complex data e. To illustrate a sequence of ideas f. To provide a change of pace.B. Overhead Transparencies 1. Advantages a. Can be used with any size group b. Presentation made in full-lighted room c. You can face the audience while viewing your visual d. Easy & inexpensive to prepare e. X-rays easily projected f. You can write or draw on visual during presentation g. Sequence of overheads easily rearranged h. Helps you stay organized 2. Disadvantages a. Preparing sophisticated overheads can be expensive b. Photographs & slides are difficult & expensive to convert to overheads c. Requires projection equipment, screen & electrical outlet d. Projector can block view of part of audience e. Equipment takes time to set-up f. Equipment can fail g. Requires skill to use well 3. When to Use Overhead Transparencies a. For general outlines, lists of items, diagrams, flow charts, charts, graphs, illustrations, drawings b. When you want to write on the visuals

c. When the room cannot or should not be darkened d. When the audience must take notes during the presentation e. When you need to make visuals in a hurry f. To provide a change of pace C. Written Handouts 1. Advantages a. Helps audience avoid note-taking because material is written down b. Provides audience with a more detailed discussion of the topic c. Can provide audience with a bibliographic resource for future investigation d. Can serve as a useful outline tool in the absence of other forms of visual aids e. Provides audience with important data or tables 2. Disadvantages a. Can be distracting if handed out prior to the presentation b. Can be too lengthy & detailed & therefore not read c. Large quantities can be expensive.3. When to Use Handouts a. When you want to leave audience with more information than you can communicate in the presentation time allowed b. When you prefer the audience not take notes during your presentation c. When you want to provide them with a general outline of your presentation & other visual tools are not available d. When you want to provide them with a copy of key data or tables.Appendix C HANDOUTS I. TYPES: include a wide range of printed or duplicated materials including outlines, charts, graphs, diagrams, drawings, reprints, reference lists and copies of papers to be presented II. DESIGN AND USE OF HANDOUTS A. Selection 1. Select materials that are appropriate to the content of the conference 2. Use materials that enhance the speaker's presentation and/or if specific reference to them is made by the speaker 3. Make sure the material is not out-of-date B. Designing Handouts 1. Make an outline of important points to be covered. Carefully structure the outline in terms of main topics and sub-topics. Organize contents carefully & use a logical sequence. 2. Avoid lengthy written explanations - the handout is a guide 3. The most useful handouts have partial information (an outline with key tables & figures)and space for taking notes (encourage note-taking) 4. Use more than one handout in preference to a lengthy one if there is a logical way of dividing the content C. Using Handouts Effectively 1. If the handout is a guide to the structure of the lecture then give it out at the beginning of the lecture before you start to speak. 2. If it is detailed information not covered during the lecture then give it out at the end of the lecture. 3. When a large number of different materials is required for the learning experience, it is less confusing if materials are arranged in packets in the order in which they will be used..Appendix D EFFECTIVE QUESTIONING I. WHY USE QUESTIONS? A. Questioning... 1. directly involves students 2. arouses student interest 3. promotes discussion

4. facilitates evaluation of student comprehension B. Plan questions ahead of time to... 1. diagnose student strengths and weaknesses 2. review and summarize material 3. identify attitudes 4. model problem-solving II. TYPES OF QUESTIONS A. Fact-based: basic knowledge, who, what, when, where, statistics. B. Interpretive: comprehension, not just recall, comparison, summarization, how, distinguish, compare, contrast, estimate, demonstrate. C, Problem-solving: judgment and application of concepts in solving a problem or making a decision. Analysis, synthesis, evaluation, why, construct, criticize, defend, design, recommend, plan. III. GUIDELINES FOR EFFECTIVE QUESTIONING A. Focus: 1. Questioning should emphasize course goals and objectives. 2. Encourage everyone to frame a response: pose the question to the entire group before calling on an individual to respond..B. Clarity: 1. Ask only one question at a time. 2. Avoid vague questions. 3. If students do not respond to a question, repeat, rephrase, or clarify the question. Provide clues. C. Variety: 1. Plan and use interpretive and problem-solving questions. 2. Do not depend on questions requiring simple recall or one-word answers. D. Wait-time: 1. Wait for at least ten seconds after posing a question to allow students time to think of answers. 2. Teachers often condition students' non-response by answering their own questions or redirecting to another student too quickly. 3. Do not rush their responses - many students are hesitant to speak up in a large group. E. Provide non-threatening feedback: 1. Listen. 2. Focus response on student's answer, not on the student, personally. 3. Respond to answers honestly, but avoid verbal (or nonverbal) putdown. 4. Praise student answers when possible. 5. Look for what is correct about an answer, not just what is incorrect. 6. Acknowledge all student contributions. 7. Avoid comparing individuals, even when discussing two or more responses to the same question. 8. Use positive reinforcement, both verbal and nonverbal..Appendix E SPEAKER FEEDBACK FORM Speaker: ___________________________________________________________________________ Person Providing Feedback: ____________________________________________________________ Please complete this sheet while you are observing each speaker. Please list those behaviors which were effective and any recommendations you have for improving the quality of the presentation. STRENGTHS RECOMMENDATIONS

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Product PolicyDocument1 pageProduct Policylakshya1985100% (5)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Sales - Related Marketing PoliciesDocument16 pagesSales - Related Marketing PoliciesSadaf Khan80% (5)

- Terminology Shito RyuDocument1 pageTerminology Shito RyuProud to be Pinoy (Devs)100% (1)

- RHCE EXAM Solution PDFDocument13 pagesRHCE EXAM Solution PDFPravind Kumar100% (1)

- Module 4Document20 pagesModule 4ragavendra4No ratings yet

- Amendment DeedDocument7 pagesAmendment DeedGlenn DomingoNo ratings yet

- High Court Says Employee With "Attitude Problem" May Be Fired From WorkDocument1 pageHigh Court Says Employee With "Attitude Problem" May Be Fired From WorkGlenn DomingoNo ratings yet

- Management Acctg HospitalityDocument338 pagesManagement Acctg HospitalityGlenn Domingo80% (5)

- Annex H Financial Bid FormDocument1 pageAnnex H Financial Bid FormGlenn Domingo100% (1)

- Accounting ManagerDocument1 pageAccounting ManagerGlenn DomingoNo ratings yet

- Final Bid Docs - Manpower ServicesDocument66 pagesFinal Bid Docs - Manpower ServicesGlenn DomingoNo ratings yet

- Glenn L. Domingo, Bsa: at Bureau of Internal Revenue - Revenue District Office 3Document2 pagesGlenn L. Domingo, Bsa: at Bureau of Internal Revenue - Revenue District Office 3Glenn DomingoNo ratings yet

- Accounting For Partnerships: Relevant To Foundations in Accountancy Paper Fa2Document8 pagesAccounting For Partnerships: Relevant To Foundations in Accountancy Paper Fa2Muhammad WaqasNo ratings yet

- Reporting - Month Vendor - Tin Branchcode Companyname Surname FirstnameDocument2 pagesReporting - Month Vendor - Tin Branchcode Companyname Surname FirstnameGlenn DomingoNo ratings yet

- Theory of Accounts With AnswersDocument35 pagesTheory of Accounts With AnswersGlenn DomingoNo ratings yet

- Module Five NotesDocument38 pagesModule Five NotesGlenn DomingoNo ratings yet

- PC KSA INV SOP 009 Axiom Logistics PolicyDocument2 pagesPC KSA INV SOP 009 Axiom Logistics PolicyGlenn DomingoNo ratings yet

- j20150910b PDFDocument4 pagesj20150910b PDFGlenn DomingoNo ratings yet

- Big Large Blank Empty Broad Wide Center Middle Cunning Clever Dangerous RiskyDocument1 pageBig Large Blank Empty Broad Wide Center Middle Cunning Clever Dangerous RiskyGlenn DomingoNo ratings yet

- Animation Animation Is The Process of Creating The ContinuousDocument1 pageAnimation Animation Is The Process of Creating The ContinuousGlenn Domingo100% (1)

- DATE: - : - Immediate SupervisorDocument1 pageDATE: - : - Immediate SupervisorGlenn DomingoNo ratings yet

- Distribution Polic1Document18 pagesDistribution Polic1Glenn DomingoNo ratings yet

- PoliciesDocument6 pagesPoliciesGlenn DomingoNo ratings yet

- Sol Man Baysa Chapter 1Document21 pagesSol Man Baysa Chapter 1Jayson Villena Malimata100% (2)

- Human Resource PoliciesDocument3 pagesHuman Resource PoliciesNaveed 205No ratings yet

- Human Resource PoliciesDocument3 pagesHuman Resource PoliciesNaveed 205No ratings yet

- Cover LetterDocument1 pageCover LetterGlenn DomingoNo ratings yet

- Cost Engineering Policy and General RequirementsDocument15 pagesCost Engineering Policy and General RequirementsAhmad Ramin AbasyNo ratings yet

- PC KSA INV SOP 009 Axiom Logistics PolicyDocument2 pagesPC KSA INV SOP 009 Axiom Logistics PolicyGlenn DomingoNo ratings yet

- PC KSA INV SOP 009 Axiom Logistics PolicyDocument2 pagesPC KSA INV SOP 009 Axiom Logistics PolicyGlenn DomingoNo ratings yet

- Purchase PolicyDocument7 pagesPurchase PolicyGlenn DomingoNo ratings yet

- Finance PoliciesDocument25 pagesFinance PoliciesarianmarikaNo ratings yet

- Supply Chain and Logistics Management: Distribution PoliciesDocument8 pagesSupply Chain and Logistics Management: Distribution PoliciesKailas Sree ChandranNo ratings yet

- Time Prepositions: In, On, At: Activity 1Document2 pagesTime Prepositions: In, On, At: Activity 1Alejandro SilvaNo ratings yet

- Eegame LogcatDocument11 pagesEegame LogcatRenato ArriagadaNo ratings yet

- Parchado SO PRODDocument17 pagesParchado SO PRODLuis Nicolas Vasquez PercovichNo ratings yet

- PC1 - Portal Essentials PDFDocument100 pagesPC1 - Portal Essentials PDFAnonymous GGuA0vbGhGNo ratings yet

- 10Document145 pages10keshavNo ratings yet

- Workshop 2 11Document9 pagesWorkshop 2 11Mauricio MartinezNo ratings yet

- 100% Guess Math 9th For All Board PDFDocument2 pages100% Guess Math 9th For All Board PDFasifali juttNo ratings yet

- Apo Sapapo - Rlgcopy THL RealignmentDocument38 pagesApo Sapapo - Rlgcopy THL RealignmentnguyencaohuygmailNo ratings yet

- Year 3 Unit 9 The HolidaysDocument8 pagesYear 3 Unit 9 The HolidaysmofardzNo ratings yet

- Alphabet Progress Monitoring Form2-6, 2009Document19 pagesAlphabet Progress Monitoring Form2-6, 2009JLHouser100% (2)

- SAP Workforce Performance Builder 9.5 SystemRequirements en-USDocument12 pagesSAP Workforce Performance Builder 9.5 SystemRequirements en-USGirija Sankar PraharajNo ratings yet

- Needs Analysis and Types of Needs AssessmentDocument19 pagesNeeds Analysis and Types of Needs AssessmentglennNo ratings yet

- Database:: Introduction To Database: A. B. C. DDocument4 pagesDatabase:: Introduction To Database: A. B. C. DGagan JosanNo ratings yet

- Automotive Software Engineering Master EnglDocument4 pagesAutomotive Software Engineering Master EnglJasmin YadavNo ratings yet

- ProxSafe Flexx16 ModuleDocument20 pagesProxSafe Flexx16 ModuleChristophe DerenneNo ratings yet

- The Twofish Encryption AlgorithmDocument5 pagesThe Twofish Encryption AlgorithmMaysam AlkeramNo ratings yet

- 23120Document7 pages23120anon_799204658No ratings yet

- READMEDocument2 pagesREADMELailaNo ratings yet

- Lefl 102Document10 pagesLefl 102IshitaNo ratings yet

- Unit-I Introduction To Iot and Python ProgrammingDocument77 pagesUnit-I Introduction To Iot and Python ProgrammingKranti KambleNo ratings yet

- BOW - Komunikasyon at PananaliksikDocument4 pagesBOW - Komunikasyon at PananaliksikDeraj LagnasonNo ratings yet

- Leasing .NET Core - Xamarin Forms + Prism - Xamarin Classic + MVVM CrossDocument533 pagesLeasing .NET Core - Xamarin Forms + Prism - Xamarin Classic + MVVM CrossJoyner Daniel Garcia DuarteNo ratings yet

- Dogme Lesson - Sussex UniversityDocument8 pagesDogme Lesson - Sussex Universitywhistleblower100% (1)

- Ict Lesson PlanDocument14 pagesIct Lesson PlanSreebu Bahuleyan100% (1)

- Ingrid Gross Resume 2023Document2 pagesIngrid Gross Resume 2023api-438486704No ratings yet

- The Past Simple Tense of The Verb TO BE1JJ-1 PDFDocument10 pagesThe Past Simple Tense of The Verb TO BE1JJ-1 PDFfrank rojasNo ratings yet