Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Testing, Assessment and Diagnosis in Counseling

Uploaded by

Dessie PierceCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Testing, Assessment and Diagnosis in Counseling

Uploaded by

Dessie PierceCopyright:

Available Formats

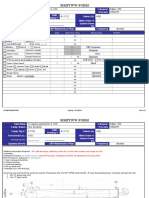

Running head: ASSESSMENT AND DIAGNOSIS

Testing, Assessment and Diagnosis in Counseling Dessie L. Pierce Student Number 23756056 Liberty University

COUN501_D01_201040 Sub-term D Deadline:12/17/2010 Instructors Name Cassandra Ferreira

ASSESSMENT AND DIAGNOSIS Date of Submission 4/29/13

Abstract Diagnosis is one of the most important tasks performed by every professional counselor. Any weakness of the diagnostic process goes to the very heart of the therapeutic process. Competent testing and proper assessment are crucial to any diagnosis. A study of the history of assessment and its role in diagnosis are informative and helpful for developing a consistent and useful diagnosis process. Also of great importance are the training and techniques of assessment and diagnostic procedures, and the acknowledgement of the historical weaknesses of these processes. The DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual), which is almost universally used, unfortunately reveals that there are problems with gender and ethnic bias which must be addressed. Also explored are the working relationships between diagnosis and the insurance industry, and between the Bible and the DSM.

ASSESSMENT AND DIAGNOSIS

Testing, Assessment and Diagnosis in Counseling There is almost no universal agreement regarding the practice of diagnosis in the field of counseling, even regarding whether or not it should be performed by counselors at all. The history of diagnosis in the profession of counseling is a long one, however, though often maligned (Hohenshil, 1993a), as its reliability does not have the best track record (Fong, 1995; Hohenshil, 1993b; Dougherty, 2005; McLaughlin, 2002). It is undeniably true, however, that all counselors diagnose, whether they do it formally or informally. Surveyed counselors who were asked how frequently they and other mental health professionals were responsible for assigning diagnoses to their clients, indicated that they were often or always responsible 85% of the time (Mead, Hohenshil & Singh, 1997). Even developmentally oriented counselors must diagnose whether the clients behavior is appropriate for their approach or the client must be referred to a specialist (Hohenshil, 1996). Diagnostic classification has become so widely used, in fact, that it is almost impossible to communicate with colleagues or mental health professionals in other fields without it (Hohenshil, 1996). Virtually all modern counselors, who have to work at the very least with licensing agencies and insurance companies, must know how to formally diagnose mental disorders, and experienced counselors know that doing so leads to more effective treatment methods (Hohenshil 1996; Hamann, 1994). Not only that, but diagnosis performed sloppily and without competence will harm clients (Hamann, 1994), and it is a process with a potential for abuse (Dougherty,

ASSESSMENT AND DIAGNOSIS 2005). Furthermore, empirical research has reached a point where it is possible for a competent counselor to choose specific, empirically verified, therapeutic techniques that are the most effective for each clients issues (Hohenshil 1996, Seligman, 1993). An accurate diagnosis also affects the course of treatment, and provides a benchmark against which the effectiveness of the treatment can be measured. (Hill, 2001; Hohenshil, 1996; Ivey & Ivey, 1999; Mead et al., 1997; Seligman & Moore, 1995).

In fact, the American Counseling Association Code of Ethics states that Counselors take special care to provide proper diagnosis of mental disorders (American Counseling Association, 2005, E.5.a., p. 12). CACREP (Counseling and Related Educational Programs) standards currently require knowledge of the principles and models of biopsychosocial assessments, case conceptualization, theories of human development and concepts of normalcy and psychopathology leading to diagnoses and appropriate counseling plans (Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs, 2009, .D.5, p. 49), as well as knowledge of the principles of diagnosis and the use of current diagnostic tools, including the current edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs, 2009, K.1, p. 22) to be taught in order for a counseling education program to be accredited. Yet until 2001, many counselor education programs did not even require students to complete a DSM course (Dougherty, 2005; Hohenshil, 1993; Mead et al., 1997). Many counselors are uncomfortable with the process of diagnosis, feeling that they are labeling their clients (Hohenshil, 1996; Mead et al., 1997; Seligman, 1999). These labels may follow clients throughout their lives and negatively affect them in many ways, impacting selfesteem, social, job, and educational opportunities, and even eligibility for medical insurance

ASSESSMENT AND DIAGNOSIS

(Dougherty, 2005; Hohenshil, 1993a; Welfel, 2002). A mental health diagnosis can also confirm a clients fear of being crazy, leading them to feel embarrassed or even hopeless (Dougherty, 2005; Welfel, 2002). Some counselors also feel that labels can cause them to dehumanize clients, which would lead them to devalue clients, discredit their concerns, and disengage from them in the therapeutic process (Hohenshil, 1996; Benson, Long, & Sporakowski, 1992, as cited in Hohenshil, 1996). Diagnosis can have a positive effect, however, like providing clients with a name for their suffering, making them more likely to seek help (Dougherty, 2005; Welfel, 2002). It can also help counselors enter the clients world through understanding what the clients symptoms mean (Hohenshil, 1993a). Some counselors have tried to help with the labeling problem by referring to their clients as people with a diagnosis, for example, a person with schizophrenia rather than a schizophrenic (Hohenshil, 1993b). By far the most commonly used system for diagnosis in the counseling profession is the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, in its various editions (Hohenshil, 1996; Mead et al., 1997; Seligman, 1999). The first edition, the DSM-I, was published in 1952, and it had 108 different categories under eight major headings (American Psychiatric Association, 1952; Hohenshil, 1993b). The DSM-II contained 185 categories (American Psychiatric Association, 1968; Hohenshil, 1993b). Both of these editions came under attack because of ambiguous criteria that resulted in low interrater reliability (Hohenshil, 1993b). The DSM-III contained 256 mental disorders and a new multiaxial system of classification (American Psychiatric Association, 1980; Hohenshil, 1993a).

ASSESSMENT AND DIAGNOSIS Research indicates that counselors use the DSM for billing insurance, case and treatment planning, communication with other professionals, education, evaluation, meeting requirements of employers and other entities such as courts and governmental agencies (Mead et al., 1997). Many counselors believe that the DSM follows a rigid medical model (Crews & Hill,

2005; Dougherty, 2005), even though the vast majority of the disorders listed are not attributable to known or presumed organic causes (Sue, Sue, & Sue, 1990, as cited in Crews & Hill, 2005). The authors of the DSM-III-R purposely avoided identifying a specific school of thought, such as medical or behavioral, but intended it to be atheoretical and purely descriptive (Cook, Warnke, & Dupuy, 1993; Crews & Hill, 2005; Fong, 1995; Hohenshil, 1993b). Other criticisms of the DSM system state that it is biased, difficult to use (Mead et al., 1997), pseudoscientific (Rabinowitz & Efron, 1997), difficult to apply to families and groups (Mead et al., 1997), and one study went so far as to say, To use the DSM-IV to diagnose relationships is tantamount to using a tape measure to determine an individuals weight, i.e. not impossible but certainly less than accurate. (Crews & Hill, 2005, p. 65). Others have countered by claiming that the limitations of the DSM system to deal with relationships are not inherent in the system itself, but in how it is used. It can be used to conceptualize systems and interactions, not just individual people (Sporakowski, 1995). It has also been pointed out that when clinicians fail to follow the DSM criteria when making diagnoses, the system can hardly be blamed for the mistakes that follow (Hohenshil, 1993b; McLaughlin, 2002; Rabinowitz & Efron, 1997). When used properly, in fact, the DSM system can be one of the many important sources of information about a client (Seligman, 1999), provide a list of characteristic behaviors and attitudes for each diagnostic category (Ivey & Ivey, 1999), enhance the selection of effective treatment procedures (Hohenshil, 1993a), provide a

ASSESSMENT AND DIAGNOSIS common language among mental health professionals (Hohenshil, 1993a), and aid in case conceptualization, treatment planning, and educating clients (Mead et al., 1997).

Beginning with DSM-III (American Psychiatric Association, 1980), the diagnosis process involved creating a comprehensive picture of the client by evaluating them according to five axes (Seligman, 1999), each axis describing a different aspect of functioning (Fong, 1995). The diagnosis was made using a menu approach, using lists of criteria which were made up of symptoms, emotions, behaviors or beliefs, and which have a required threshold number. For example, a diagnosis might be indicated by four or more of the criteria on the list (Fong, 1995). Axis I issues are egodystonic, that is, they are not perceived by the client to be a part of the self. Axis II issues are egosyntonic, perceived as an integral part of the self (Fong, 1995). The other axes describe medical problems, psychosocial problems and adaptation. Counselors should determine a full five-axial diagnosis on all clients (Fong, 1993). Although the words testing and assessment are often used interchangeably, standardized tests and self-report inventories are only a few of the many types of assessment done by competent counselors. Assessment is anything performed in the process of collecting information for use in diagnosis (Hohenshil, 1996). Assessment involves a variety of formal and informal methods, including personal interviews, questionnaires, checklists, behavioral observations, analysis of case records, information gleaned from significant others, as well as consultation with other professionals (Dougherty, 2005; Fong, 1995; Hill & Ridley, 2001; Hohenshil, 1993a; Welfel, 2002). The ACA Code of Ethics and Standards of Practice states that assessment techniques including the personal interview should be carefully selected and properly utilized to promote client well-being while diminishing potential harm to clients (American Counseling Association,

ASSESSMENT AND DIAGNOSIS 2005, E.5.a). Licensing and certification standards also require some knowledge of tests and assessment. Of course, these are minimum standards and do not fulfill the degree of proficiency that should be the goal of every counselor (Zytowski, 1994). For personal interviews, many counselor educators strongly encourage the use of a semistructured interview guide, to avoid subjective impressions and judgments based on only a few symptoms (Fong, 1995; Morey & Ochoa, 1989, as cited in Fong, 1995). While it seems obvious that assessment is important at the start of the therapeutic

relationship, it is also important in every stage. First, the counselor uses assessment techniques to gather information for at least a tentative diagnosis and treatment plan. During treatment, assessment data collected will provide information about progress made, and assist in making the decision of when to terminate the therapeutic relationship. Follow-up assessment might include client self-reports, behavioral observation, and/or reports by significant others, for the purpose of determining the lasting effects of treatment (Hohenshil, 1993b; Sporakowski, 1995). Diagnosis is the interpretation of the information gathered through assessment, using a diagnostic classification system (Hohenshil, 1996). There are many ways to improve the accuracy of diagnosis, but the most efficient way is through effective training. The Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP) and state licensure agencies now require knowledge of psychopathology and diagnostic skills for program approval and licensure (Hohenshil, 1996; Mead et al., 1997), and at least 90% of counselor education programs offer some training in the diagnosis of mental and emotional disorders (Hamann, 1994; Hohenshil, 1992; Seligman, 1999), mostly in the DSM system (Hohenshil, 1996; Mead et al., 1997), although some have called for a an even more aggressive approach (Hamann, 1994). In fact, it has been suggested that the low interrater reliability rate obtained by some DSM-III-R

ASSESSMENT AND DIAGNOSIS (APA, 1987) studies reflects poor diagnostic training (Hohenshil, 1996), as good to excellent interrater reliability has been found for even the most difficult diagnoses when clinicians were studied who were well trained in the use of systematic interviewing procedures and were able to apply the DSM-III-R diagnostic criteria correctly.

While some find the DSM system to be too distant from their professional value of caring (Ivey & Ivey, 1999), most call for counselor educators and supervisors to train new counselors to use it in a way that maximizes its benefits while minimizing its drawbacks (Mead et al., 1997). Although much focus has gone into improving the DSM system and other tools for diagnosis, this has not resulted in an increased diagnostic accuracy (Rabinowitz & Efron, 1997). Accuracy will only improve with better training in the use of these tools as well as the best diagnostic techniques. Some suggestions in the literature for improving the process of diagnosis include delaying diagnosis to improve accuracy (Dougherty, 2005; Fong, 1993; Hill & Crews, 2005; Hill & Ridley, 2001; McLaughlin, 2002; Rabinowitz & Efron, 1997), thinking of diagnosis as an ongoing process rather than a rigid one (Dougherty, 2005; Hohenshil, 1993a; Hohenshil, 1996), basing diagnostic decisions on more than one assessment instrument (McLaughlin, 2002), assuring that all the DSM criteria for a particular disorder have been considered (McLaughlin, 2002), considering all of the pros and cons of a particular diagnosis to guard against confirmatory bias (McLaughlin, 2002), writing down expectations about clients to make them explicit and thereby reducing the likelihood of self-fulfilling prophecies (McLaughlin, 2002), focusing on the atypical aspects of a case (McLaughlin, 2002), gathering counterevidence (Rabinowitz & Efron, 1997), consulting with peers (McLaughlin, 2002), keeping in mind that the DSM favors some groups over others (McLaughlin, 2002; Garb, 1998, as cited in McLaughlin, 2002), and taking

ASSESSMENT AND DIAGNOSIS advantage of all opportunities for training in diagnosis and the use of the DSM system (McLaughlin, 2002).

10

The literature provides some insight into the sorts of errors that contribute most heavily to misdiagnosis. These are referred to as information processing errors (McLaughlin, 2002; Rabinowitz & Efron, 1997) and contribute to such flawed thinking as stereotyping, which is making a decision based on only a few common features or symptoms (McLaughlin, 2002; Rabinowitz & Efron, 1997), self-fulfilling prophecy, which is acting on an expectation in a way that confirms it (McLaughlin, 2002), data availability and vividness, which is the practice of categorizing something on the basis of its familiarity, ease of recall, or clarity (McLaughlin, 2002), self-confirmatory bias, which is categorizing something only based on confirming evidence (McLaughlin, 2002), ignoring data in favor of personal experience, (McLaughlin, 2002), giving precedence to anecdotal information over systematic information (McLaughlin, 2002), relying on intuition and first impressions (McLaughlin, 2002; Rabinowitz & Efron, 1997), and assuming in the first stage of diagnosis that pathology is present, thus diagnosing pathology even when it is not there (McLaughlin, 2002; Rabinowitz & Efron, 1997). Being aware of these errors helps counselors guard against falling into them. Charges of gender and racial bias have been aimed at the DSM system, claiming that it operates from a Eurocentric male point of view (Cook, Warnke, & Dupuy, 1993; Dougherty, 2005; Ivey & Ivey, 1999), that it tends to overdiagnose women and underdiagnose men (Cook, Warnke, & Dupuy, 1993), and that both men and women in less traditional roles are more likely to be diagnosed with pathology than are those in traditional gender roles (Cook, Warnke, & Dupuy, 1993). Proponents of the system, while admitting that such a bias unquestionably exists, tend to blame it on the mind-set of the clinicians (Cook, Warnke, & Dupuy, 1993; Crews & Hill,

ASSESSMENT AND DIAGNOSIS 2005; Fong, 1993), rather than on the system itself, and reiterate that gender bias is minimized

11

when the DSM system is used in a competent manner by well-trained clinicians who follow the diagnostic criteria. Some counselors have even suggested the addition of a Global Assessment of Culture, Age, and Gender Scale, which would enrich understanding and use of Axis V, which would be a genuinely productive contribution of the ACA to a truly culture-centered, contextually aware DSM-IV (Hinkle, 1999, as cited in Ivey & Ivey, 1999; Ivey & Ivey, 1999). But the strongest criticism of the DSM system comes from marriage and family and group therapists who complain that the DSM is oriented to the diagnosis of individuals and doesnt lend itself to the diagnosis of systems and groups (Crews & Hill, 2005; Hill & Crews, 2005; Hohenshil, 1996; Ivey & Ivey, 1999; Sporakowski, 1995). The only codes related to relational diagnoses are the so-called V codes (Crews & Hill, 2005; Sporakowski, 1995) still referred to as such even though they are no longer called V codes in the latest revision (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Unfortunately, the V codes are not eligible for reimbursement from third party payers (Crews & Hill, 2005; Hamann, 1994), which brings up further issues for family and group counselors. A DSM diagnosis is usually required for reimbursement (Crews & Hill, 2005; Hohenshil, 1996), in fact some studies have found that marriage and family counselors primary use of the DSM is to diagnose clients for insurance purposes (Dougherty, 2005; Hamann, 1994; Hohenshil, 1996; Mead et al., 1997). They are forced to choose between billing the correct diagnosis, even when a family may not be able to afford to pay for the unreimbursed therapy, or billing the third party payer with a somewhat misleading individual diagnosis, a practice that is apparently not at all rare, even though it is unethical and fraudulent (Crews & Hill, 2005; Dougherty, 2005; Hamann, 1994; Mead, Hohenshil, & Singh, 1997; Welfel, 2002). Keep in mind that such a

ASSESSMENT AND DIAGNOSIS diagnosis can also follow a client for years, with possible negative consequences (Dougherty,

12

2005; Hohenshil, 1993a; Welfel, 2002). It is no wonder that some feel that the use of the DSM is primarily for financial gain. As in every area of life, the Bible has some guidance for us on this important topic. Even though the process of diagnosis performed by a counselor can be used by God to begin a very powerful life-changing process in a client, it is a difficult process, and also has great potential to cause harm. The Bible guides us to be humble (2 Samuel 22: 28, Psalm 25:9, Ephesians 4:2, James 4:10, to name but a few), to not think of ourselves as better than others (Philippians 2:3), to not judge others in such a way that we would be judged the same way (Matthew 7:1), and to do all things in love (1 Corinthians 16:14, John 13:35). We can never go wrong if we treat others the way we would want to be treated if we were in their situation. Irvin D. Yalom (2002) asks an eloquent question in his book The Gift of Therapy, If you were in personal psychotherapy or are considering it, what DSM-IV diagnosis do you think your therapist could justifiably use to describe someone as complicated as you?" (p. 5, as cited in Dougherty, 2005).

ASSESSMENT AND DIAGNOSIS References American Counseling Association. (2005). ACA Code of Ethics. Alexandria, VA: Author.

13

American Psychiatric Association. (1952). Diagnostic and statistical manual: Mental disorders. Washington, DC: Author. American Psychiatric Association. (1968). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: Author. American Psychiatric Association. (1980). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. (3rd ed.). Washington, DC: Author. American Psychiatric Association. (1987). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. (3rd ed., rev.). Washington. DC: Author. American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. (4th ed., text rev.). Washington, DC: Author. Benson, M. J., Long, J. K., & Sporakowski, M. J. (1992). Teaching psychopathology and the DSM-III-R from a family systems therapy perspective. Family Relations, 41(2), 135. Boughner, S. R., Hayes, S. F., Bubenzer, D. L., & West, J. D. (1994). Use of standardized assessment instruments by marital and family therapists: A survey. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 20, 69-75. Cook, E. P., Warnke, M. & Dupuy, P. (1993). Gender bias and the DSM-III-R. Counselor Education and Supervision, 32(4), 311-322. Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP). (2009). 2009 standards. Alexandria, VA: Author. Crews, J. A. & Hill, N. R. (2005). Diagnosis in marriage and family counseling: An ethical double bind. The Family Journal, 13(1), 63-66. DOI: 10.1177/1066480704269281

ASSESSMENT AND DIAGNOSIS

14

Dougherty, J. L. (2005). Ethics in case conceptualization and diagnosis: Incorporating a medical model into the developmental counseling tradition. Counseling and Values, 49, 132-140. Downing, H., & Paradise, L. (1989). Using the DSM-III-R in counseling. Journal of Counseling & Development, 68, 226-227. Fong, M. L. (1993). Teaching assessment and diagnosis within a DSM-III-R framework. Education & Supervision, 32(4), 276. Fong, M. L. (1995). Assessment and DSM-IV diagnosis of personality disorders: A primer for counselors. Journal of Counseling & Development, 73(6), 635-639. Garb, H. N. (1998). Studying the clinician: Judgment research and psychological assessment. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Hamann, E. E. (1994). Clinicians and diagnosis; Ethical concerns and clinical competence. Journal of Counseling & Development, 72(3), 259-260. Hill, N. R. & Crews, J. A. (2005). The application of an ethical lens to the issue of diagnosis in marriage and family counseling. The Family Journal, 13(2), 176-180. Hill, C. L., & Ridley, C. R. (2001). Diagnostic decision making: Do counselors delay final judgments? Journal of Counseling & Development, 79(1), 98-105. Hinkle, J. S. (1999). A voice from the trenches: A reaction to Ivey and Ivey (1998). Journal of Counseling & Development, 77, 474-483. Hohenshil, T. H. (1992). DSM-IV progress report. Journal of Counseling & Development, 71, 224-227. Hohenshil, T. H. (1993a). Teaching the DSM-III-R in counselor education. Counselor Education and Supervision, 32(4), 267-275.

ASSESSMENT AND DIAGNOSIS Hohenshil, T. H. (1993b). Assessment and diagnosis in the Journal of Counseling & Development. Journal of Counseling and Development, 72(1), 7. Hohenshil, T. H. (1996). Editorial: Role of assessment and diagnosis in counseling. Journal of Counseling & Development, 75(1), 64-67.

15

Ivey, A. E., & Ivey, M. B. (1999). Toward a developmental diagnostic and statistical manual: The vitality of a contextual framework. Journal of Counseling and Development, 77, 484490. McLaughlin, J. E. (2002). Reducing diagnostic bias. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 24(3), 256-269. Mead, M. A., Hohenshil, T. H., & Singh, K. (1997). How the DSM system is used by clinical counselors: A national study. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 19(4), 383-401. Moore, B. M., & Seligman, L. (1995). Diagnosis of mood disorders. Journal of Counseling & Development, 74(1), 65-69. Morey, L. C., & Ochoa, E. S. (1989). An investigation of adherence to diagnostic criteria: Clinical diagnosis of the DSM-III personality disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders, 3, 180-192. Rabinowitz, J., & Efron, N. J. (1997). Diagnosis, dogmatism, and rationality. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 19, 4056. Seligman, L. (1999). Twenty years of diagnosis and the DSM. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 21(3), 229-239. Sporakowski, M. J. (1995). Assessment and diagnosis in marriage and family counseling. Journal of Counseling & Development, 74(1), 60-64.

ASSESSMENT AND DIAGNOSIS Sue, D., Sue, D., & Sue, S. (1990). Understanding abnormal behavior. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. Welfel, E. R. (2002). Ethics in counseling and psychotherapy: Standards, research, and emerging issues (2nd ed.). Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks-Cole. Yalom, I. D. (2002). The gift of therapy. New York: HarperCollins. Zytowski, D. G. (1994). Tests and counseling: We are still married and living in discriminant analysis. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 26, 219-223.

16

You might also like

- Community Program Development Needs Assessment EvaluationDocument2 pagesCommunity Program Development Needs Assessment EvaluationFaranNo ratings yet

- Definition of Counselling and PsychotherapyDocument6 pagesDefinition of Counselling and PsychotherapyLeonard Patrick Faunillan BaynoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7 Mood DisordersDocument29 pagesChapter 7 Mood DisordersPeng Chiew LowNo ratings yet

- Trauma-Informed Sebm Poster FinalDocument1 pageTrauma-Informed Sebm Poster Finalapi-510430920No ratings yet

- Counseling Case Conceptualization Andrews FinalDocument11 pagesCounseling Case Conceptualization Andrews Finalapi-269876030100% (2)

- NCE Study GuideDocument62 pagesNCE Study GuideSusana MunozNo ratings yet

- 29 Gerald Corey SosDocument21 pages29 Gerald Corey SosGiorgos LexouritisNo ratings yet

- Zniber Group Counseling GuideDocument45 pagesZniber Group Counseling GuideIsmael RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Counseling Psychology - 1Document52 pagesCounseling Psychology - 1sania zafarNo ratings yet

- Guide For SW Exam and LSWDocument111 pagesGuide For SW Exam and LSWMadonna Ang100% (1)

- Career Counseling Case BookDocument5 pagesCareer Counseling Case BookΕυγενία ΔερμιτζάκηNo ratings yet

- Counselors For Social Justice Position Statement On DSM-5Document10 pagesCounselors For Social Justice Position Statement On DSM-5Julie R. AncisNo ratings yet

- Hamlet's Seven Soliloquies AnalyzedDocument3 pagesHamlet's Seven Soliloquies Analyzedaamir.saeedNo ratings yet

- Group CounselingDocument5 pagesGroup CounselingAlam ZebNo ratings yet

- Theoretical Orientation PaperDocument15 pagesTheoretical Orientation Paper000766401100% (3)

- The Code of Conduct For PsychologistsDocument3 pagesThe Code of Conduct For PsychologistsAnkit HasijaNo ratings yet

- 5772 Testing & Assessment in CounselingDocument16 pages5772 Testing & Assessment in CounselingDean ErhanNo ratings yet

- Case Conceptualization and Treatment Plan for Alcohol Use DisorderDocument9 pagesCase Conceptualization and Treatment Plan for Alcohol Use DisorderNORAZLINA BINTI MOHMAD DALI / UPM100% (2)

- Grade 2 - PAN-ASSESSMENT-TOOLDocument5 pagesGrade 2 - PAN-ASSESSMENT-TOOLMaestro Varix100% (4)

- NTC Counseling and PsychotherapyDocument32 pagesNTC Counseling and Psychotherapychester chester100% (1)

- What S in A Case Formulation PDFDocument10 pagesWhat S in A Case Formulation PDFNicole Flores MuñozNo ratings yet

- CounsellingDocument8 pagesCounsellingsmigger100% (4)

- Supervisors Manual Feb 15Document64 pagesSupervisors Manual Feb 15Kiesha BentleyNo ratings yet

- CounselingDocument23 pagesCounselingrashmi patooNo ratings yet

- (Evolutionary Psychology) Virgil Zeigler-Hill, Lisa L. M. Welling, Todd K. Shackelford - Evolutionary Perspectives On Social Psychology (2015, Springer) PDFDocument488 pages(Evolutionary Psychology) Virgil Zeigler-Hill, Lisa L. M. Welling, Todd K. Shackelford - Evolutionary Perspectives On Social Psychology (2015, Springer) PDFVinicius Francisco ApolinarioNo ratings yet

- CBT Paper Final BerryDocument18 pagesCBT Paper Final Berryapi-284381567No ratings yet

- Family and Group CounsellingDocument15 pagesFamily and Group CounsellingJAMUNA SHREE PASUPATHINo ratings yet

- Treviranus ThesisDocument292 pagesTreviranus ThesisClaudio BritoNo ratings yet

- Evaluating Alcohol and Drug Abuse Treatment Effectiveness: Recent AdvancesFrom EverandEvaluating Alcohol and Drug Abuse Treatment Effectiveness: Recent AdvancesLinda Carter SobellNo ratings yet

- Rights and Responsibilities in Behavioral Healthcare: For Clinical Social Workers, Consumers, and Third PartiesFrom EverandRights and Responsibilities in Behavioral Healthcare: For Clinical Social Workers, Consumers, and Third PartiesNo ratings yet

- Worksheets From The BFRB Recovery WorkbookDocument64 pagesWorksheets From The BFRB Recovery WorkbookMarla DeiblerNo ratings yet

- 10 Things Case ConceptualizationDocument2 pages10 Things Case ConceptualizationAndreeaNo ratings yet

- Defense MechanismsDocument4 pagesDefense MechanismsJuanCarlos YogiNo ratings yet

- Group Counseling HandoutDocument18 pagesGroup Counseling HandoutAbu UbaidahNo ratings yet

- Group CounselingDocument18 pagesGroup CounselingAureen Razali100% (2)

- Multicultural Counseling Applied To Vocational RehabilitationDocument16 pagesMulticultural Counseling Applied To Vocational RehabilitationMichele Eileen Salas100% (1)

- Application Performance Management Advanced For Saas Flyer PDFDocument7 pagesApplication Performance Management Advanced For Saas Flyer PDFIrshad KhanNo ratings yet

- Group CounselingDocument17 pagesGroup CounselingnajarardnusNo ratings yet

- Theories of PersonalityDocument26 pagesTheories of PersonalityMilleran Frouh OcheaNo ratings yet

- Gender Issues in Career CounselingDocument2 pagesGender Issues in Career CounselingNur Qatrunnada100% (2)

- AIDS Trauma and Support Group Therapy: Mutual Aid, Empowerment, ConnectionFrom EverandAIDS Trauma and Support Group Therapy: Mutual Aid, Empowerment, ConnectionNo ratings yet

- The Magic Limits in Harry PotterDocument14 pagesThe Magic Limits in Harry Potterdanacream100% (1)

- Personal Theory Reality TherapyDocument18 pagesPersonal Theory Reality Therapyapi-285903956100% (1)

- Guidance and CounselingDocument35 pagesGuidance and CounselingKirthi KomalaNo ratings yet

- Practical Research 1 - Quarter 1 - Module 1 - Nature and Inquiry of Research - Version 3Document53 pagesPractical Research 1 - Quarter 1 - Module 1 - Nature and Inquiry of Research - Version 3Iris Rivera-PerezNo ratings yet

- Ethical and Social Considerations in TestingDocument24 pagesEthical and Social Considerations in TestingArnel G GutierrezNo ratings yet

- Counseling Theories Final PaperDocument11 pagesCounseling Theories Final Paperapi-334628919No ratings yet

- AP Therapy ExamDocument6 pagesAP Therapy ExamDghdk NfksdnfNo ratings yet

- DocDocument83 pagesDocJangNo ratings yet

- Family TherapyDocument8 pagesFamily TherapyManoj NayakNo ratings yet

- Multicultural Counseling PortfolioDocument11 pagesMulticultural Counseling Portfolioapi-285240070No ratings yet

- Termination During The Counseling Process: Function, Timing & Related IssuesDocument4 pagesTermination During The Counseling Process: Function, Timing & Related IssuesA.100% (1)

- Career Development TheoryDocument4 pagesCareer Development TheoryLuchian GeaninaNo ratings yet

- Assessment in Counselling and Guidance 2MBDocument302 pagesAssessment in Counselling and Guidance 2MBShraddha Sharma0% (1)

- The History of CounselingDocument10 pagesThe History of CounselingDana Ruth Manuel100% (3)

- Acceptance and Completion of Treatment Among Sex OffendersDocument17 pagesAcceptance and Completion of Treatment Among Sex OffenderspoopmanNo ratings yet

- Lazarus Basid IDDocument7 pagesLazarus Basid IDmiji_ggNo ratings yet

- Psychology Assignment 3Document5 pagesPsychology Assignment 3sara emmanuelNo ratings yet

- APA style reference informed consent confidentialityDocument23 pagesAPA style reference informed consent confidentialityCristina RîndașuNo ratings yet

- Personal Theory of Counseling Pape1Document19 pagesPersonal Theory of Counseling Pape1Steven Adams100% (1)

- Psychological TestingDocument68 pagesPsychological TestingLennyNo ratings yet

- Psychological Intervention PaperDocument16 pagesPsychological Intervention PaperElenaNo ratings yet

- Disciplines of CounselingDocument9 pagesDisciplines of CounselingStrawberrie LlegueNo ratings yet

- Theories of CounselingDocument10 pagesTheories of Counselingབཀྲཤིས ཚེརིངNo ratings yet

- Reality TherapyDocument14 pagesReality TherapyHerc SabasNo ratings yet

- US. History of Guidance and CounsellingDocument19 pagesUS. History of Guidance and CounsellingMs. Rachel SamsonNo ratings yet

- MSW Program at CSIDocument2 pagesMSW Program at CSIdiosjirehNo ratings yet

- IC 4060 Design NoteDocument2 pagesIC 4060 Design Notemano012No ratings yet

- Sustainable Marketing and Consumers Preferences in Tourism 2167Document5 pagesSustainable Marketing and Consumers Preferences in Tourism 2167DanielNo ratings yet

- Information BulletinDocument1 pageInformation BulletinMahmudur RahmanNo ratings yet

- Haryana Renewable Energy Building Beats Heat with Courtyard DesignDocument18 pagesHaryana Renewable Energy Building Beats Heat with Courtyard DesignAnime SketcherNo ratings yet

- Plo Slide Chapter 16 Organizational Change and DevelopmentDocument22 pagesPlo Slide Chapter 16 Organizational Change and DevelopmentkrystelNo ratings yet

- MAS-06 WORKING CAPITAL OPTIMIZATIONDocument9 pagesMAS-06 WORKING CAPITAL OPTIMIZATIONEinstein Salcedo100% (1)

- Simptww S-1105Document3 pagesSimptww S-1105Vijay RajaindranNo ratings yet

- TOPIC - 1 - Intro To Tourism PDFDocument16 pagesTOPIC - 1 - Intro To Tourism PDFdevvy anneNo ratings yet

- Daft Presentation 6 EnvironmentDocument18 pagesDaft Presentation 6 EnvironmentJuan Manuel OvalleNo ratings yet

- Final DSL Under Wire - FinalDocument44 pagesFinal DSL Under Wire - Finalelect trsNo ratings yet

- Batman Vs Riddler RiddlesDocument3 pagesBatman Vs Riddler RiddlesRoy Lustre AgbonNo ratings yet

- AReviewof Environmental Impactof Azo Dyes International PublicationDocument18 pagesAReviewof Environmental Impactof Azo Dyes International PublicationPvd CoatingNo ratings yet

- Verbos Regulares e IrregularesDocument8 pagesVerbos Regulares e IrregularesJerson DiazNo ratings yet

- GPAODocument2 pagesGPAOZakariaChardoudiNo ratings yet

- San Mateo Daily Journal 05-06-19 EditionDocument28 pagesSan Mateo Daily Journal 05-06-19 EditionSan Mateo Daily JournalNo ratings yet

- A1. Coordinates System A2. Command Categories: (Exit)Document62 pagesA1. Coordinates System A2. Command Categories: (Exit)Adriano P.PrattiNo ratings yet

- Mr. Bill: Phone: 086 - 050 - 0379Document23 pagesMr. Bill: Phone: 086 - 050 - 0379teachererika_sjcNo ratings yet

- Jillian's Student Exploration of TranslationsDocument5 pagesJillian's Student Exploration of Translationsjmjm25% (4)

- M Information Systems 6Th Edition Full ChapterDocument41 pagesM Information Systems 6Th Edition Full Chapterkathy.morrow289100% (24)

- Computer Conferencing and Content AnalysisDocument22 pagesComputer Conferencing and Content AnalysisCarina Mariel GrisolíaNo ratings yet

- Legend of The Galactic Heroes, Vol. 10 Sunset by Yoshiki Tanaka (Tanaka, Yoshiki)Document245 pagesLegend of The Galactic Heroes, Vol. 10 Sunset by Yoshiki Tanaka (Tanaka, Yoshiki)StafarneNo ratings yet

- Gambaran Kebersihan Mulut Dan Karies Gigi Pada Vegetarian Lacto-Ovo Di Jurusan Keperawatan Universitas Klabat AirmadidiDocument6 pagesGambaran Kebersihan Mulut Dan Karies Gigi Pada Vegetarian Lacto-Ovo Di Jurusan Keperawatan Universitas Klabat AirmadidiPRADNJA SURYA PARAMITHANo ratings yet

- Product Manual: Control Cabinet M2001Document288 pagesProduct Manual: Control Cabinet M2001openid_6qpqEYklNo ratings yet