Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Agile

Uploaded by

Amandeep Singh DhillonCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Agile

Uploaded by

Amandeep Singh DhillonCopyright:

Available Formats

Introduction Agile software development is a conceptual framework for software engineering th at promotes development iterations throughout the life-cycle

of the project. There are many agile development methods; most minimize risk by developing softw are in short amounts of time. Software developed during one unit of time is refe rred to as an iteration, which may last from one to four weeks. Each iteration i s an entire software project: including planning, requirements analysis, design, coding, testing, and documentation. An iteration may not add enough functionali ty to warrant releasing the product to market but the goal is to have an availab le release (without bugs) at the end of each iteration. At the end of each itera tion, the team re-evaluates project priorities. Agile methods emphasize face-to-face communication over written documents. Most agile teams are located in a single open office sometimes referred to as a bullp en. At a minimum, this includes programmers and their "customers" (customers def ine the product; they may be product managers, business analysts, or the clients ). The office may include testers, interaction designers, technical writers, and managers. Agile methods also emphasize working software as the primary measure of progress . Combined with the preference for face-to-face communication, agile methods pro duce very little written documentation relative to other methods. This has resul ted in criticism of agile methods as being undisciplined. Contents: History Agile software development is a conceptual framework for software engine ering that promotes development iterations throughout the life-cycle of the proj ect. There are many agile development methods; most minimize risk by developing softw are in short amounts of time. Software developed during one unit of time is refe rred to as an iteration, which may last from one to four weeks. Each iteration i s an entire software project: including planning, requirements analysis, design, coding, testing, and documentation. An iteration may not add enough functionali ty to warrant releasing the product to market but the goal is to have an availab le release (without bugs) at the end of each iteration. At the end of each itera tion, the team re-evaluates project priorities. Agile methods emphasize face-to-face communication over written documents. Most agile teams are located in a single open office sometimes referred to as a bullp en. At a minimum, this includes programmers and their "customers" (customers def ine the product; they may be product managers, business analysts, or the clients ). The office may include testers, interaction designers, technical writers, and managers. Agile methods also emphasize working software as the primary measure of progress . Combined with the preference for face-to-face communication, agile methods pro duce very little written documentation relative to other methods. This has resul ted in criticism of agile methods as being undisciplined. The modern definition of agile software development evolved in the mid 1990s as part of a reaction against "heavyweight" methods, as typified by a heavily regul ated, regimented, micro-managed use of the waterfall model of development. The p rocesses originating from this use of the waterfall model were seen as bureaucra tic, slow, demeaning, and inconsistent with the ways that software developers ac tually perform effective work. A case can be made that agile and iterative devel opment methods are a return to development practice seen early in the history of

software development. Initially, agile methods were called "lightweight methods ." In 2001, prominent members of the community met at Snowbird, Utah, and adopte d the name "agile methods." Later, some of these people formed The Agile Allianc e, a non-profit organization that promotes agile development. Methodologies similar to Agile created prior to 2000 include Scrum (1986), Crystal Clear, Extreme Programming (1996), Adaptive Software Development, Feature Drive n Development, and DSDM (1995). Extreme Programming (usually abbreviated as "XP") was created by Kent Beck in 19 96 as a way to rescue the struggling Chrysler Comprehensive Compensation (C3) pr oject. While that project was eventually canceled, the methodology was refined b y Ron Jeffries' full-time XP coaching, public discussion on Ward Cunningham's Po rtland Pattern Repository wiki and further work by Beck, including a book in 199 9. Elements of Extreme Programming appear to be based on Scrum and Ward Cunningh am's Episodes pattern language. Principles behind agile methods The Agile Manifesto Agile methods are a family of development processes, not a single approa ch to software development. In 2001, 17 prominent figures in the field of agile development (then called "light-weight methodologies") came together at the Snow bird ski resort in Utah to discuss ways of creating software in a lighter, faste r, more people-centric way. They created the Agile Manifesto, widely regarded as the canonical definition of agile development, and accompanying agile principle s. Some of the principles behind the Agile Manifesto are Customer satisfaction by rapid, continuous delivery of useful software Working software is delivered frequently (weeks rather than months) Working software is the principal measure of progress Even late changes in requirements are welcomed Close, daily cooperation between business people and developers Face-to-face conversation is the best form of communication Projects are built around motivated individuals, who should be trusted Continuous attention to technical excellence and good design Simplicity Self-organizing teams Regular adaptation to changing circumstances The publishing of the manifesto spawned a movement in the software industry know n as agile software development. In 2005, Alistair Cockburn and Jim Highsmith gathered another group of people ma nagement experts, this time and wrote an addendum, known as the PM Declaration o f Interdependence. Comparison with other methods Agile methods are sometimes characterized as being at the opposite end o f the spectrum from "plan-driven" or "disciplined" methodologies. This distincti on is misleading, as it implies that agile methods are "unplanned" or "undiscipl ined". A more accurate distinction is to say that methods exist on a continuum f rom "adaptive" to "predictive". Agile methods exist on the "adaptive" side of th is continuum. Adaptive methods focus on adapting quickly to changing realities. When the needs of a project change, an adaptive team changes as well. An adaptive team will ha ve difficulty describing exactly what will happen in the future. The further awa y a date is, the more vague an adaptive method will be about what will happen on

that date. An adaptive team can report exactly what tasks are being done next w eek, but only which features are planned for next month. When asked about a rele ase six months from now, an adaptive team may only be able to report the mission statement for the release, or a statement of expected value vs. cost. Predictive methods, in contrast, focus on planning the future in detail. A predi ctive team can report exactly what features and tasks are planned for the entire length of the development process. Predictive teams have difficulty changing di rection. The plan is typically optimized for the original destination and changi ng direction can cause completed work to be thrown away and done over differentl y. Predictive teams will often institute a change control board to ensure that o nly the most valuable changes are considered. Agile methods have much in common with the "Rapid Application Development" techn iques from the 1980/90s as espoused by James Martin and others Suitability of agile methods Although agile methods differ in their practices, they share a number of common characteristics, including iterative development, and a focus on interac tion, communication, and the reduction of resource-intensive intermediate artifa cts. The suitability of agile methods in general can be examined from multiple p erspectives. From a product perspective, agile methods are more suitable when re quirements are emergent and rapidly changing; they are less suitable for systems that have high criticality, reliability and safety requirements, though there i s no complete consensus on this point. From an organizational perspective, the s uitability can be assessed by examining three key dimensions of an organization: culture, people, and communication. In relation to these areas a number of key success factors have been identified (Cohen et al., 2004): The culture of the organization must be supportive of negotiation People must be trusted Fewer staff, with higher levels of competency Organizations must live with the decisions developers make Organizations need to have an environment that facilitates rapid communicati on between team members Agile data The most important factor is probably project size. As size grows, faceto-face communication becomes more difficult. Therefore, most agile methods are more suitable for projects with small teams, with fewer than 20 to 40 people. La rge scale agile software development remains an active research area. Another serious problem is that initial assumptions or overly rapid requirements gathering up front may result in a large drift from an optimal solution, especi ally if the client defining the target product has poorly formed ideas of their needs. Similarly, given the nature of human behaviour, it's easy for a single "d ominant" developer to influence or even pull the design of the target in a direc tion not necessarily appropriate for the project. Historically, the developers c an, and often do, impose solutions on a client then convince the client of the a ppropriateness of the solution, only to find at the end that the solution is act ually unworkable. In theory, the rapidly iterative nature should limit this, but it assumes that there's a negative feedback, or even appropriate feedback. If n ot, the error could be magnified rapidly. This can be alleviated by separating the requirements gathering into a separate phase (a common element of Agile systems), thus insulating it from the developer 's influence, or by keeping the client in the loop during development by having them continuously trying each release. The problem there is that in the real wor ld, most clients are unwilling to invest this much time. It also makes QAing a p

roduct difficult since there are no clear test goals that don't change from rele ase to release. In order to determine the suitability of agile methods individually, a more soph isticated analysis is required. The DSDM approach, for example, provides a so-ca lled suitability-filter for this purpose. The DSDM and Feature Driven Development (FDD) methods, are claimed to be suitabl e for any agile software development project, regardless of situational characte ristics. Agile methods and method tailoring A comparison of agile methods will reveal that they support different ph ases of a software development life-cycle to varying degrees. This individual ch aracteristic of agile methods can be used as a selection criterion for selecting candidate agile methods. In general a sense of project speed, complexity, and c hallenges will guide you to the best agile methods to implement and how complete ly to adopt them. Agile development has been widely documented (see Experience Reports, below, as well as Beck, and Boehm and Turner as working well for small (<10 developers) co -located teams. Agile development is expected to be particularly suitable for te ams facing unpredictable or rapidly changing requirements. Agile development's applicability to the following scenarios is open to question : Large scale development efforts (>20 developers), though scaling strategies and evidence to the contrary have been described. Distributed development efforts (non-co-located teams). Strategies have been described in Bridging the Distance and Using an Agile Software Process with Off shore Development Mission- and life-critical efforts Command-and-control company cultures It is worth noting that several large scale project successes have been document ed by organisations such as BT which have had several hundred developers situate d in the UK, Ireland and India, working collaboratively on projects and using Ag ile methodologies. While questions undoubtedly still arise about the suitability of some Agile methods to certain project types, it would appear that scale or g eography, by themselves, are not necessarily barriers to success. Barry Boehm and Richard Turner suggest that risk analysis be used to choose betw een adaptive ("agile") and predictive ("plan-driven") methods. The authors sugge st that each side of the continuum has its own home ground: Agile home ground: Low criticality Senior developers Requirements change very often Small number of developers Culture that thrives on chaos Plan-driven home ground: High criticality Junior developers Requirements don't change too often Large number of developers

Culture that demands order Agile methods One of the most challenging parts of an agile project is being agile wit h data. Typically this is where projects hit legacy systems and legacy requireme nts. Many times working with data systems requires lengthy requests to teams of specialists who are not used to the speed of an agile project and insist on exac t and complete specifications. Typically the database world will be at odds with agile development. The agile framework seeks as much as possible to remove thes e bottlenecks with techniques such as generative data models making change fast. Models for data serve another purpose, often a change of one table column can b e a critical issue requiring months to rebuild all the dependent applications. An agile approach would try to encapsulate data dependencies to go fast and allo w change. But ultimately relational data issues will be important for agile proj ects and are a common blockage point. As such agile projects are best suited whe re projects don't contain big legacy databases. It still isn't the end of the wo rld because if you can build your data dependencies to be agile regardless of le gacy systems you will start to prove the merit of the approach as all other syst ems go through tedious changes to catch up with data changes while in the protec ted agile data system the change would be trivial. Measuring agility While agility is seen by many as a means to an end, a number of approach es have been proposed to quantify agility. Agility Index Measurements (AIM) scor e projects against a number of agility factors to achieve a total. The similarly -named Agility Measurement Index, scores developments against five dimensions of a software project (duration, risk, novelty, effort, and interaction). Other te chniques are based on measurable goals. Another study using fuzzy mathematics ha s suggested that project velocity can be used as a metric of agility. While such approaches have been proposed to measure agility, the practical appli cation of such metrics has yet to be seen. Criticism Agile development is sometimes criticized as cowboy coding. Extreme Prog ramming's initial buzz and controversial tenets, such as pair programming and co ntinuous design, have attracted particular criticism, such as McBreen and Boehm and Turner. Many of the criticisms, however, are believed by Agile practitioners to be misunderstandings of agile development. In particular, Extreme Programming is reviewed and critiqued by Matt Stephens's and Doug Rosenberg's Extreme Programming Refactored. Criticisms include: Lack of structure and necessary documentation Only works with senior-level developers Incorporates insufficient software design Requires too much cultural change to adopt Can lead to more difficult contractual negotiations Can be very inefficient -- if the requirements for one area of code change t hrough various iterations, the same programming may need to be done several time s over. Whereas if a plan was there to be followed, a single area of code is exp ected to be written once. Impossible to develop realistic estimates of work effort needed to provide a quote, because at the beginning of the project no one knows the entire scope/re quirements Drastically increases the chances of scope creep due to the lack of detailed

requirements documentation The criticisms regarding insufficient software design and lack of documentation are addressed by the Agile Modeling method which can easily be tailored into agi le processes such as XP. Agile software development has been criticized because it will not bring about t he claimed benefits when programmers of average ability use this methodology, an d most development teams are indeed likely to be made up of people with average (or below) skills. Agile Principles There are ten principles of Agile Testing: Agile Principle #1: Active user involvement is imperative It's not always possible to have users directly involved in development projects , particularly if the Agile Development project is to build a product where the real end users will be external customers or consumers. In this event it is imperative to have a senior and experienced user representat ive involved throughout. Not convinced? Here's 16 reasons why! Requirements are clearly communicated and understood (at a high level) at th e outset Requirements are prioritised appropriately based on the needs of the user an d market Requirements can be clarified on a daily basis with the entire project team, rather than resorting to lengthy documents that aren't read or are misunderstoo d Emerging requirements can be factored into the development schedule as appro priate with the impact and trade-off decisions clearly understood The right product is delivered As iterations of the product are delivered, that the product meets user expe ctations The product is more intuitive and easy to use The user/business is seen to be interested in the development on a daily bas is The user/business sees the commitment of the team Developers are accountable, sharing progress openly with the user/business e very day There is complete transparency as there is nothing to hide The user/business shares responsibility for issues arising in development; i t s not a customer-supplier relationship but a joint team effort Timely decisions can be made, about features, priorities, issues, and when t he product is ready

Responsibility is shared; the team is responsible together for delivery of t he product Individuals are accountable, reporting for themselves in daily updates that involve the user/business When the going gets tough, the whole team - business and technical - work to gether! ----------------------------------------------------------Agile Principle #2: Agile Development teams must be empowered An Agile Development project team must include all the necessary team members to make decisions, and make them on a timely basis. Active user involvement is one of the key principles to enable this, so the user or user representative from the business must be closely involved on a daily ba sis. The project team must be empowered to make decisions in order to ensure that it is their responsibility to deliver the product and that they have complete owner ship. Any interference with the project team is disruptive and reduces their mot ivation to deliver. The team must establish and clarify the requirements together, prioritise them t ogether, agree to the tasks required to deliver them together, and estimate the effort involved together. It may seem expedient to skip this level of team involvement at the beginning. I t s tempting to get a subset of the team to do this (maybe just the product owner and analyst), because it s much more efficient. Somehow we ve all been trained over the years that we must be 100% efficient (or more!) and having the whole team in volved in these kick-off steps seems a very expensive way to do things. However this is a key principle for me. It ensures the buy-in and commitment fro m the entire project team from the outset; something that later pays dividends. When challenges arise throughout the project, the team feels a real sense of own ership. And then it's doesn't seem so expensive. ----------------------------------------------------------Agile Principle #3: Time waits for no man! In Agile Development,requirements evolve, but timescales are fixed. This is in stark contrast to a traditional development project, where one of the earliest goals is to capture all known requirements and baseline the scope so t hat any other changes are subject to change control. Traditionally, users are educated that it s much more expensive to change or add r equirements during or after the software is built. Some organisations quote some impressive statistics designed to frighten users into freezing the scope. The r esult: It becomes imperative to include everything they can think of in fact eve rything they ever dreamed of! And what s more, it s all important for the first rele ase, because we all know Phase 2 s are invariably hard to get approved once 80% of the benefits have been realised from Phase 1. Ironically, users may actually use only a tiny proportion of any software produc t, perhaps as low as 20% or less, yet many projects start life with a bloated sc ope. In part, this is because no-one is really sure at the outset which 20% of t he product their users will actually use. Equally, even if the requirements are carefully analysed and prioritised, it is impossible to think of everything, thi ngs change, and things are understood differently by different people.

Agile Development works on a completely different premise. Agile Development wor ks on the premise that requirements emerge and evolve, and that however much ana lysis and design you do, this will always be the case because you cannot really know for sure what you want until you see and use the software. And in the time you would have spent analysing and reviewing requirements and designing a soluti on, external conditions could also have changed. So if you believe that point that no-one can really know what the right solution is at the outset when the requirements are written it s inherently difficult, per haps even practically impossible, to build the right solution using a traditiona l approach to software development. Traditional projects fight change, with change control processes designed to min imise and resist change wherever possible. By contrast, Agile Development projec ts accept change; in fact they expect it. Because the only thing that s certain in life is change. There are different mechanisms in Agile Development to handle this reality. In A gile Development projects, requirements are allowed to evolve, but the timescale is fixed. So to include a new requirement, or to change a requirement, the user or product owner must remove a comparable amount of work from the project in or der to accommodate the change. This ensures the team can remain focused on the agreed timescale, and allows the product to evolve into the right solution. It does, however, also pre-suppose t hat there s enough non-mandatory features included in the original timeframes to a llow these trade-off decisions to occur without fundamentally compromising the e nd product. So what does the business expect from its development teams? Deliver the agreed business requirements, on time and within budget, and of course to an acceptable quality. All software development professionals will be well aware that you can not realistically fix all of these factors and expect to meet expectations. Some thing must be variable in order for the project to succeed. In Agile Development , it is always the scope (or features of the product) that are variable, not the cost and timescale. Although the scope of an Agile Development project is variable, it is acknowledg ed that only a fraction of any product is really used by its users and therefore that not all features of a product are really essential. For this philosophy to work, it s imperative to start development (dependencies permitting) with the cor e, highest priority features, making sure they are delivered in the earliest ite rations. Unlike most traditional software development projects, the result is that the bu siness has a fixed budget, based on the resources it can afford to invest in the project, and can make plans based on a launch date that is certain. ----------------------------------------------------------------------Agile Principle #4: Agile requirements are barely sufficient! Agile Development teams capture requirements at a high level and on a piecemeal basis, just-in-time for each feature to be developed. Agile requirements are ideally visual and should be barely sufficient, i.e. the absolute minimum required to enable development and testing to proceed with reas onable efficiency. The rationale for this is to minimise the time spent on anyth ing that doesn t actually form part of the end product. Agile Development can be mistaken by some as meaning there s no process; you just make things up as you go along in other words, JFDI! That approach is not so muc

h Agile but Fragile! Although Agile Development is much more flexible than more traditional developme nt methodologies, Agile Development does nevertheless have quite a bit of rigour and is based on the fairly structured approach of lean manufacturing as pioneer ed by Toyota. However any requirements captured at the outset should be captured at a high lev el and in a visual format, perhaps for example as a storyboard of the user inter face. At this stage, requirements should be understood enough to determine the o utline scope of the product and produce high level budgetary estimates and no mo re. Ideally, Agile Development teams capture these high level requirements in worksh ops, working together in a highly collaborative way so that all team members und erstand the requirements as well as each other. It is not necessarily the remit of one person, like the Business Analyst in more traditional projects, to gather the requirements independently and write them all down; it s a joint activity of the team that allows everyone to contribute, challenge and understand what s neede d. And just as importantly, why. XP (eXtreme Programming) breaks requirements down into small bite-size pieces ca lled User Stories. These are fundamentally similar to Use Cases but are lightwei ght and more simplistic in their nature. An Agile Development team (including a key user or product owner from the busine ss) visualises requirements in whiteboarding sessions and creates storyboards (s equences of screen shots, visuals, sketches or wireframes) to show roughly how t he solution will look and how the user s interaction will flow in the solution. Th ere is no lengthy requirements document or specification unless there is an area of complexity that really warrants it. Otherwise the storyboards are just annot ated and only where necessary. A common approach amongst Agile Development teams is to represent each requireme nt, use case or user story, on a card and use a T-card system to allow stories t o be moved around easily as the user/business representative on the project adju sts priorities. Requirements are broken down into very small pieces in order to achieve this; an d actually the fact it s going on a card forces it to be broken down small. The ad vantage this has over lengthy documentation is that it's extremely visual and ta ngible; you can stand around the T-card system and whiteboard discussing progres s, issues and priorities. The timeframe of an Agile Development is fixed, whereas the features are variabl e. Should it be necessary to change priority or add new requirements into the pr oject, the user/business representative physically has to remove a comparable am ount of work from scope before they can place the new card into the project. This is a big contrast to a common situation where the business owner sends nume rous new and changed requirements by email and/or verbally, somehow expecting th e new and existing features to still be delivered in the original timeframes. Tr aditional project teams that don't control changes can end up with the dreaded s cope creep, one of the most common reasons for software development projects to fail. Agile teams, by contrast, accept change; in fact they expect it. But they manage change by fixing the timescales and trading-off features. Cards can of course be backed up by documentation as appropriate, but always the principle of agile development is to document the bare minimum amount of inform

ation that will allow a feature to be developed, and always broken down into ver y small units. Using the Scrum agile management practice, requirements (or features or stories, whatever language you prefer to use) are broken down into tasks of no more than 16 hours (i.e. 2 working days) and preferably no more than 8 hours, so progress can be measured objectively on a daily basis. ------------------------------------------------------------------------Agile Principle #5: How d'you eat an elephant? One bite at a time! Likewise, agile software development projects are delivered in small bite-sized pieces, delivering small, incremental *releases* and iterati ng. In more traditional software development projects, the (simplified) lifecycle is Analyse, Develop, Test - first gathering all known requirements for the whole p roduct, then developing all elements of the software, then testing that the enti re product is fit for release. In agile software development, the cycle is Analyse, Develop, Test; Analyse, Dev elop, Test; and so on... doing each step for each feature, one feature at a time . Advantages of this iterative approach to software development include:

Reduced risk: clear visibility of what's completed to date throughout a proj ect Increased value: delivering some benefits early; being able to release the p roduct whenever it's deemed good enough, rather than having to wait for all inte nded features to be ready More flexibility/agility: can choose to change direction or adapt the next i terations based on actually seeing and using the software Better cost management: if, like all-too-many software development projects, you run over budget, some value can still be realised; you don't have to scrap the whole thing if you run short of funds For this approach to be practical, each feature must be fully developed, to the extent that it's ready to be shipped, before moving on. Another practicality is to make sure features are developed in *priority* order, not necessarily in a logical order by function. Otherwise you could run out of time, having built some of the less important features - as in agile software de velopment, the timescales are fixed. Building the features of the software broad but shallow is also advisable for the same reason. Only when you've completed all your must-have features, move on to the should-haves, and only then move on to the could-haves. Otherwise you can ge t into a situation where your earlier features are functionally rich, whereas la ter features of the software are increasingly less sophisticated as time runs ou t. Try to keep your product backlog or feature list expressed in terms of use cases , user stories, or features - not technical tasks. Ideally each item on the list should always be something of value to the user, and always deliverables rather than activities so you can 'kick the tyres' and judge their completeness, quali

ty and readiness for release. ---------------------------------------------------------------------Agile Principle #6: Fast but not so furious! Agile software development is all about frequent delivery of products. In a trul y agile world, gone are the days of the 12 month project. In an agile world, a 3 -6 month project is strategic! Nowhere is this more true than on the web. The web is a fast moving place. And w ith the luxury of centrally hosted solutions, there's every opportunity to break what would have traditionally been a project into a list of features, and deliv er incrementally on a very regular basis - ideally even feature by feature. On the web, it's increasingly accepted for products to be released early (when t hey're basic, not when they're faulty!). Particularly in the Web 2.0 world, it's a kind of perpetual beta. In this situation, why wouldn't you want to derive so me benefits early? Why wouldn't you want to hear real user/customer feedback bef ore you build 'everything'? Why wouldn't you want to look at your web metrics an d see what works, and what doesn't, before building 'everything'? And this is only really possible due to some of the other important principles o f agile development. The iterative approach, requirements being lightweight and captured just-in-time, being feature-driven, testing integrated throughout the l ifecycle, and so on. So how frequent is *frequent*? Scrum says break things into 30 day Sprints. That's certainly frequent compared to most traditional software development proj ects. Consider a major back-office system in a large corporation, with traditional pro jects of 6-12 months+, and all the implications of a big rollout and potentially training to hundreds of users. 30 days is a bit too frequent I think. The overh ead of releasing the software is just too large to be practical on such a regula r basis. ----------------------------------------------------------------------Agile Principle #7: "done" means "DONE!" In agile development, "done" should really mean "DONE!". Features developed within an iteration (Sprint in Scrum), should be 100% complet e by the end of the Sprint. Too often in software development, "done" doesn't really mean "DONE!". It doesn' t mean tested. It doesn't necessarily mean styled. And it certainly doesn't usua lly mean accepted by the product owner. It just means developed. In an ideal situation, each iteration or Sprint should lead to a release of the product. Certainly that's the case on BAU (Business As Usual) changes to existin g products. On projects it's not feasible to do a release after every Sprint, ho wever completing each feature in turn enables a very precise view of progress an d how far complete the overall project really is or isn't. So, in agile development, make sure that each feature is fully developed, tested , styled, and accepted by the product owner before counting it as "DONE!". And i f there's any doubt about what activities should or shouldn't be completed withi n the Sprint for each feature, "DONE!" should mean shippable. The feature may rely on other features being completed before the product could

really be shipped. But the feature on its own merit should be shippable. So if y ou're ever unsure if a feature is 'done enough', ask one simple question: "Is th is feature ready to be shipped?". It's also important to really complete each feature before moving on to the next ... Of course multiple features can be developed in parallel in a team situation. Bu t within the work of each developer, do not move on to a new feature until the l ast one is shippable. This is important to ensure the overall product is in a sh ippable state at the end of the Sprint, not in a state where multiple features a re 90% complete or untested, as is more usual in traditional development project s. In agile development, "done" really should mean "DONE!". -------------------------------------------------------------------------Agile Principle #8: Enough's enough! Pareto's law is more commonly known as the 80/20 rule. The theory is about the l aw of distribution and how many things have a similar distribution curve. This m eans that *typically* 80% of your results may actually come from only 20% of you r efforts! areto's law can be seen in many situations - not literally 80/20 but certainly t he principle that the majority of your results will often come from the minority of your efforts. So the really smart people are the people who can see (up-front without the bene fit of hind-sight) *which* 20% to focus on. In agile development, we should try to apply the 80/20 rule, seeking to focus on the important 20% of effort that ge ts the majority of the results. If the quality of your application isn't life-threatening, if you have control o ver the scope, and if speed-to-market is of primary importance, why not seek to deliver the important 80% of your product in just 20% of the time? In fact, in t hat particular scenario, you could ask why you would ever bother doing the last 20%? that doesn't mean your product should be fundamentally flawed, a bad user experi ence, or full of faults. It just means that developing some features, or the ric hness of some features, is going the extra mile and has a diminishing return tha t may not be worthwhile. So does that statement conflict with my other recent post: "done means DONE!"? N ot really. Because within each Sprint or iteration, what you *do* choose to deve lop *does* need to be 100% complete within the iteration. -------------------------------------------------------------------------Agile Principle #9: Agile testing is not for dummies! In agile development, testing is integrated throughout the lifecycle; testing th e software continuously throughout its development. Agile development does not have a separate test phase as such. Developers are mu ch more heavily engaged in testing, writing automated repeatable unit tests to v alidate their code. Apart from being geared towards better quality software, this is also important to support the principle of small, iterative, incremental releases. With automated repeatable unit tests, testing can be done as part of the build, ensuring that all features are working correctly each time the build is produced . And builds should be regular, at least daily, so integration is done as you go

too. The purpose of these principles is to keep the software in releasable condition throughout the development, so it can be shipped whenever it's appropriate. The XPeXtreme Programming) agile methodology goes further still. XP recommends t est driven development, writing tests before writing the software. But testing shouldn't only be done by developers throughout the development. The re is still a very important role for professional testers, as we all know "deve lopers can't test for toffee!" :-) The role of a tester can change considerably in agile development, into a role m ore akin to quality assurance than purely testing. There are considerable advant ages having testers involved from the outset This is compounded further by the lightweight approach to requirements in agile development, and the emphasis on conversation and collaboration to clarify requi rements more than the traditional approach of specifications and documentation. Although requirements can be clarified in some detail in agile development (as l ong as they are done just-in-time and not all up-front), it is quite possible fo r this to result in some ambiguity and/or some cases where not all team members have the same understanding of the requirements. So what does this mean for an agile tester? A common concern from testers moving to an agile development approach - particularly from those moving from a much m ore formal environment - is that they don't know precisely what they're testing for. They don't have a detailed spec to test against, so how can they possibly t est it? Even in a more traditional development environment, I always argued that testers could test that software meets a spec, and yet the product could still be poor quality, maybe because the requirement was poorly specified or because it was cl early written but just not a very good idea in the first place! A spec does not necessarily make the product good! In agile development, there's a belief that sometimes - maybe even often - these things are only really evident when the software can be seen running. By delive ring small incremental releases and by measuring progress only by working softwa re, the acid test is seeing the software and only then can you really judge for sure whether or not it's good quality. Agile testing therefore calls for more judgement from a tester, the application of more expertise about what's good and what's not, the ability to be more flexi ble and having the confidence to work more from your own knowledge of what good looks like. It's certainly not just a case of following a test script, making su re the software does what it says in the spec. And for these reasons, agile testing is not for dummies! -------------------------------------------------------------------------------Agile Principle #10: No place for snipers! Agile development relies on close cooperation and collaboration between all team members and stakeholders. Agile development principles include keeping requirements and documentation ligh tweight, and acknowledging that change is a normal and acceptable reality in sof tware development.

This makes close collaboration particularly important to clarify requirements ju st-in-time and to keep all team members (including the product owner) 'on the sa me page' throughout the development. You certainly can't do away with a big spec up-front *and* not have close collab oration. You need one of them that's for sure. And for so many situations the la tter can be more effective and is so much more rewarding for all involved! In situations where there is or has been tension between the development team an d business people, bringing everyone close in an agile development approach is a kin to a boxer keeping close to his opponent, so he can't throw the big punch! : -) But unlike boxing, the project/product team is working towards a shared goal, cr eating better teamwork, fostering team spirit, and building stronger, more coope rative relationships. There are many reasons to consider the adoption of agile development, and in the near future I'm going to outline "10 good reasons to go agile" and explain some of the key business benefits of an agile approach. If business engagement is an issue for you, that's one good reason to go agile y ou shouldn't ignore. --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

You might also like

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- T3 International Section MapDocument7 pagesT3 International Section MapAbhishek DeyNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- T3 Departure Main Hall: International Security Domestic SecurityDocument7 pagesT3 Departure Main Hall: International Security Domestic Securitymann4u3072No ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- AsdaDocument4 pagesAsdaAmandeep Singh DhillonNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- IELTS Essential Words PDFDocument45 pagesIELTS Essential Words PDFyesumovs100% (1)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Mo VDocument1 pageMo VAmandeep Singh DhillonNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

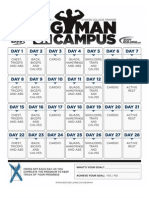

- BIGMAN Print CalendarDocument3 pagesBIGMAN Print CalendarAmandeep Singh DhillonNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- ClarksDocument1 pageClarksAmandeep Singh DhillonNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- RootDocument1 pageRootAmandeep Singh DhillonNo ratings yet

- IIBA Academic Membership Oct 2011Document2 pagesIIBA Academic Membership Oct 2011Aman2Shorty16121984No ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- MBADocument64 pagesMBAAmandeep Singh DhillonNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Level 2012 Release Plan v1.1Document10 pagesLevel 2012 Release Plan v1.1ilie_vlassaNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Agile Business Analyst: By: Mike Cottmeyer, V. Lee HensonDocument5 pagesThe Agile Business Analyst: By: Mike Cottmeyer, V. Lee HensonMudit KapoorNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Expert Level Syllabus Improving The Test Process Release V1 0 2Document75 pagesExpert Level Syllabus Improving The Test Process Release V1 0 2Vinay KumarNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- MBADocument64 pagesMBAAmandeep Singh DhillonNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Istqb Ctal Examination Information Sheet v2012Document4 pagesIstqb Ctal Examination Information Sheet v2012Liviu AmisculeseiNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Agile Business Analyst: By: Mike Cottmeyer, V. Lee HensonDocument5 pagesThe Agile Business Analyst: By: Mike Cottmeyer, V. Lee HensonMudit KapoorNo ratings yet

- Sunny - Jain - Scrum Master - Project Manager - Canada PR - 1107378630Document5 pagesSunny - Jain - Scrum Master - Project Manager - Canada PR - 1107378630Anup SatishNo ratings yet

- KT Internship ReportDocument16 pagesKT Internship ReportcharenbahaeddinehemmemNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Kaedah Analisis Dan Reka Bentuk Bab 1Document27 pagesKaedah Analisis Dan Reka Bentuk Bab 1MOHD AFFENDI BIN JOULANo ratings yet

- The Future of Leadership - The Agile Leader™ - LinkedInDocument6 pagesThe Future of Leadership - The Agile Leader™ - LinkedInpuskesmas bungursari2019No ratings yet

- Scrum Training - SalesforceDocument83 pagesScrum Training - SalesforcediegoconeNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- HRMS ProposalDocument12 pagesHRMS ProposalPaul KamaraNo ratings yet

- Ws Report AgaileDocument36 pagesWs Report AgaileAhmed AlnagarNo ratings yet

- UGRD-CS6302 Application Lifecycle Management FINAL EXAMDocument66 pagesUGRD-CS6302 Application Lifecycle Management FINAL EXAMpatricia geminaNo ratings yet

- SAFe 5.0 Scrum Master SSM Q10Document19 pagesSAFe 5.0 Scrum Master SSM Q10fran rNo ratings yet

- What Do You Mean by Software Crisis? Explain With Examples. How Can Software Crisis Can Be Minimized?Document11 pagesWhat Do You Mean by Software Crisis? Explain With Examples. How Can Software Crisis Can Be Minimized?Gagan PandeyNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Unit 4Document7 pagesUnit 4Sonia AroraNo ratings yet

- JamaicaDocument16 pagesJamaicarajaNo ratings yet

- Internship Report DCCDocument33 pagesInternship Report DCCdjankoulovelygraceNo ratings yet

- OM Assignment 01-Vikrant Singh Tomar (19MBAR0331)Document11 pagesOM Assignment 01-Vikrant Singh Tomar (19MBAR0331)Vikrant SinghNo ratings yet

- PMP 6 ChangesDocument4 pagesPMP 6 Changesbalaji100% (1)

- Agile Fundamentals-AashuDocument8 pagesAgile Fundamentals-AashuPrashant GuptaNo ratings yet

- Pokharel Muna ResumeDocument5 pagesPokharel Muna ResumeH JKNo ratings yet

- Android Based Health Care ManagementDocument18 pagesAndroid Based Health Care ManagementAnne LoraigneNo ratings yet

- Aot Version 2Document26 pagesAot Version 2Phuoc HoNo ratings yet

- Intermediate Developer - SAP Analytics CloudDocument4 pagesIntermediate Developer - SAP Analytics CloudAJNo ratings yet

- Certified Scrum MasterDocument5 pagesCertified Scrum MasterNeelakandan Siavathanu0% (3)

- Software Metrics For Agile Software DevelopmentDocument6 pagesSoftware Metrics For Agile Software DevelopmentmirwaisdoostNo ratings yet

- Se Gtu Paper Questions Analysis: UNIT-1 Introduction To Software and Software EngineeringDocument5 pagesSe Gtu Paper Questions Analysis: UNIT-1 Introduction To Software and Software Engineeringroy104646No ratings yet

- Agile Intro To Customer v2 (Long)Document21 pagesAgile Intro To Customer v2 (Long)karuneshnNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- PAW Savers Zamboanga Pet Adoption System 1Document90 pagesPAW Savers Zamboanga Pet Adoption System 1Christian SanohNo ratings yet

- VinayKumar - Resume - QA Lead - 14yrsDocument4 pagesVinayKumar - Resume - QA Lead - 14yrsRaju GbNo ratings yet

- Product Roadmap Guide by ProductPlanDocument68 pagesProduct Roadmap Guide by ProductPlananikbiswasNo ratings yet

- Effect Oriented Programming PreviewDocument254 pagesEffect Oriented Programming PreviewSayid IbrihenNo ratings yet

- Lesson PlaningDocument3 pagesLesson Planing2226 Bharat PrajapatiNo ratings yet

- Agile-Transformation KPMGDocument42 pagesAgile-Transformation KPMGmario5681No ratings yet