Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Responding to Diversity in Education

Uploaded by

yankumi07Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Responding to Diversity in Education

Uploaded by

yankumi07Copyright:

Available Formats

Responding to Diversity

Jon Gaffney April 17, 2005

Students do not all learn in the same ways. As educators, we need to be mindful of this and respond accordingly. If we do not, then we run the risk of treating students with disabilities, students below the poverty line, and students of different race or gender than our own as unintelligent, incapable of understanding or achieving. Studies have shown that rather than trying to educate everyone in a homogenous way, we do far better to diversify our techniques and attempt to connect with our students as they are rather than as we are. Gender bias is a prevalent problem in science, most notably in the field of physics. While females generally seem as capable as males with regards to subject matter and problem-solving, very few earn PhDs or become physicists. Guzzetti and Williams spoke about this issue from the perspective of the students, in addition to that of the teachers. They found that even when the teachers of the classes were aware of some bias on their parts (such as calling on males more frequently) and attempted to compensate, they overlooked more subtle sources bias. For example, refutation, a proven effective instructional method, was favored by males but not females, who felt that their input was often undervalued or dismissed by the males who were perceived as opinionated and dominating. Because of their lack of self-confidence and fear of being wrong, both of which were fed into by the (perceived) male-dominated culture of the classroom, the female students were unintentionally sidelined. Meanwhile, Hesse (and anthropologist) saw that while the dividing line was not crisply between males and females, there was a dividing line between two groups of

students: those who played at being scientists, and those who viewed their role as primarily receiving an education. Females almost exclusively fell into the latter category, while most of the males fell into the former. Hesse observed that the students were receiving mixed messages about what was important during their schooling: some professors valued play seemingly above coursework, while others discouraged it. Here, again, the perceived male-dominated culture of play tended to sideline the students who thought their role was primarily completion of problem sets. Both of these gender articles make it clear that students as a whole do not engage in physics in the same way. Females tend to be more likely to focus on the explicit goals of the assignment (often through invisible and unrewarded creative means), while males tend to respond better to internally motivated science-type games and discussions. However, due to the nature of the males preference (and the already male-dominated physics field), females are often discriminated against improperly (and usually unintentionally). Understanding that females (and some males) need direct support and encouragement through appreciation of their problem-solving efforts, and that it is often uncomfortable for them to engage in refutation-type exercises with males gives the instructors a way to combat this pervasive bias. In addition to gender, race is often a stumbling block to education. Since most teachers are white, communication with African-American (and other minority) students is often difficult. One error has been to try to insert culture into education rather than provide education within the framework of the culture. Ladson-Billings discusses a threeyear long study of successful teachers of African-American students where the culture framed the education. Certain commonalities emerged among these teachers, such as their

choice to teach in their schools, their understanding of their role as a part of the community at large, their loose, fluid roles with their students (allowing themselves to learn from the students), and their belief that all students can learn. Moreover, having a culturally relevant pedagogy involves three criteria that teachers should use as guides: the demand of academic success from their students (often channeled through AfricanAmerican boys, who have social power), appreciation of the students culture and refusal to remove the students culture from their education, and the demand that their students develop a broad sociopolitical consciousness and engage critically in the world. Hence, students education is enabled by the integration of the local culture. Often connected to race is the issue of poverty. However, poverty is more general in that it refers to the students socio-economic status which affects students of all race and color, usually in rural or inner-city schools. Habermann addresses this issue in a charged way, indicating the prevailing attitude of schools before presenting hope in the form of signs of effective teaching. Because research indicated that a leading indicator of performance on achievement tests is the students socio-economic status, many teachers take a why bother? attitude with them into the classroom. However, rather than spending their time as laborers and executors of pragmatic deeds such as paperwork, punishment, and monitoring, teachers would be better off as professionals; there are a number of signs of good teaching and none of them involve the amount of paperwork a teacher gets through. Rather, good teaching is evident when students are involved in issues they regard as vital, or when they are reflecting on their own lives, or when they question prevailing assumptions; whenever students see big ideas, are involved in course planning, and redo their work it is likely that learning and effective teaching are taking place.

Habermann is apparently encouraging teachers not to treat their students as objects to be dealt with, but rather as subjects who can help the teacher reach the end products that are desired. Finally, some students are different not due to race, gender, or socio-economic status, but rather by the fact that they are disabled. Many negative assumptions surround the issue of including them with mainstream students in general education classes; the article Including Students with Disabilities Into the General Education Science Classroom takes a look at those assumptions and argues them. The authors found that when the science teachers were properly trained, these assumptions were simply wrong. Students with disabilities did not worsen the behavior of the general education classes; often behavioral incidents decreased. Also, students with disabilities tended to improve their social standing and relieve some of the stigma associated with them in the eyes of their peers. Most importantly, general educations students did not perform more poorly on standardized tests; while they performed the same as before, the disabled students performed much better when in the mainstream classrooms than when segregated. The largest contribution to these improvements was the new methods that the teachers took into the classroom, with the disabled students in mind. Hands-on curricula, such as FOSS, appealed to the students with disabilities without missing mainstream students. Hence, taking the consideration of diverse needs into the classroom led to improved performance. Through these five examples of gender, race, socio-economic standing, and differing ability levels, we see the recurring theme. Teachers must make every effort to involve all of their students. This involvement necessarily means respecting the culture from which they come, acknowledging that they learn in a myriad of appropriate ways, and

assuming that they are each capable of learning. Simply expecting to educate students by following a set catchall procedure is misguided and sure to fail. Both the students and the teacher must create dynamic, safe, fluid culture in the classroom, and the objective of this culture should be to engage in learning and professional development, not simply to fulfill the requirements of a job.

The five articles summarized above are:

Guzzetti and Williams (1996). Gender, Text, and Discussion: Examining Intellectual Safety in the Science Classroom. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 33 (1), 5-20. Hasse, C. (2002). Gender Diversity in Play With Physics: The Problem of Premises for Participation in Activities. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 9 (4), 250-26. Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). But Thats Just Good Teaching! The Case for Culturally Relevant Pedagogy. Theory Into Practice, 34 (3), 159-163. Habermann, M. (1991). The Pedagogy of Poverty Versus Good Teaching. Phi Delta Kappan, 73, 290-294. (Author unknown). (year unknown). Including Students with Disabilities into the General Education Science Classroom. (info unknown).

You might also like

- Socialization and Education: Education and LearningFrom EverandSocialization and Education: Education and LearningNo ratings yet

- Functions of EducationDocument5 pagesFunctions of EducationMarvie Cayaba GumaruNo ratings yet

- Educ 275 FinalDocument9 pagesEduc 275 Finalapi-349855318No ratings yet

- Langhout and Mitchell - Hidden CurriculuDocument22 pagesLanghout and Mitchell - Hidden CurriculuDiana VillaNo ratings yet

- The Teacher As Warm DemanderDocument6 pagesThe Teacher As Warm Demanderapi-123492799No ratings yet

- Education and Gender EqualityDocument11 pagesEducation and Gender EqualityMichaela Kristelle SanchezNo ratings yet

- University of Illinois Press Feminist TeacherDocument10 pagesUniversity of Illinois Press Feminist TeacherAndrea LopezNo ratings yet

- Gender Discrimination in Hidden CurriculumDocument15 pagesGender Discrimination in Hidden CurriculumManerisSanchez PenamoraNo ratings yet

- Education: Where Do We Go From HereDocument8 pagesEducation: Where Do We Go From Hereapi-280992885No ratings yet

- Annotated BibliographyDocument13 pagesAnnotated Bibliographyapi-295669671No ratings yet

- Taylor & Francis, LTDDocument8 pagesTaylor & Francis, LTDapi-277504949No ratings yet

- Warm Demander ArticleDocument7 pagesWarm Demander Articleapi-302779030No ratings yet

- Working Class Under-Achievement Is Mainly The Result of In-School Factors.Document6 pagesWorking Class Under-Achievement Is Mainly The Result of In-School Factors.Azaa RegmiNo ratings yet

- Does Co-Education Disadvantage Female StudentsDocument5 pagesDoes Co-Education Disadvantage Female StudentsTahir MehmoodNo ratings yet

- Sociological Theories of Conflict and Consensus in EducationDocument3 pagesSociological Theories of Conflict and Consensus in EducationMarly Espiritu75% (4)

- StratificationDocument8 pagesStratificationabubakar usmanNo ratings yet

- Reviewed by Nina Ellis-Hervey Stephen F. Austin State University United StatesDocument8 pagesReviewed by Nina Ellis-Hervey Stephen F. Austin State University United StatesostugeaqpNo ratings yet

- Sociology HW 2Document5 pagesSociology HW 2Joyce Ama WilliamsNo ratings yet

- Rica C. AlonzabeRochelle B. VerganioDocument6 pagesRica C. AlonzabeRochelle B. VerganioROCHELLE VERGANIONo ratings yet

- Post Modernism: Modernity: Knowledge and StatusDocument10 pagesPost Modernism: Modernity: Knowledge and StatusAnusha AsimNo ratings yet

- Poverty Remains Main Obstacle to Educational EqualityDocument5 pagesPoverty Remains Main Obstacle to Educational EqualityFinch SlimesNo ratings yet

- Toward A Critical Pedagogy of Engagement For Alienated Youth: Insights From Freire TheoryDocument11 pagesToward A Critical Pedagogy of Engagement For Alienated Youth: Insights From Freire TheoryTawsif Shafayet AliNo ratings yet

- Essentialism in EducationDocument5 pagesEssentialism in EducationNgatia SamNo ratings yet

- Male Underachievement Literature ReviewDocument3 pagesMale Underachievement Literature ReviewJames SeanNo ratings yet

- Do You Like Your Teachers? A Quantitative Research On Students' Perceptions of Teacher Gender CharacteristicsDocument8 pagesDo You Like Your Teachers? A Quantitative Research On Students' Perceptions of Teacher Gender CharacteristicsAlthea RivadeloNo ratings yet

- Introduction GS (Final)Document16 pagesIntroduction GS (Final)Sara JavedNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 54.204.47.237 On Thu, 11 Jun 2020 17:01:45 UTCDocument8 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 54.204.47.237 On Thu, 11 Jun 2020 17:01:45 UTCKirkNo ratings yet

- The Sociology of Education. Theoretical PerspectivesDocument3 pagesThe Sociology of Education. Theoretical PerspectivesarloNo ratings yet

- Week 4 Discussion Question-Rosalyn Dunevant-AshleyDocument3 pagesWeek 4 Discussion Question-Rosalyn Dunevant-Ashleyrosalynashley1826No ratings yet

- But Thats Just Good TeachingDocument8 pagesBut Thats Just Good Teachingapi-608207346No ratings yet

- Conroy 269053 Etl414 Sem 1 2014Document12 pagesConroy 269053 Etl414 Sem 1 2014api-250019457No ratings yet

- Diversity, Learning StyleDocument21 pagesDiversity, Learning StyleSalvador Briones IINo ratings yet

- Empowering Students With Disabilities: Cedric TimbangDocument26 pagesEmpowering Students With Disabilities: Cedric TimbangJerico ArayatNo ratings yet

- Exploring Culturally Responsive Assessment PracticesDocument2 pagesExploring Culturally Responsive Assessment Practicestan s yeeNo ratings yet

- Pupil Subculture Is More Significant in Explaining Underachievement in Education.Document3 pagesPupil Subculture Is More Significant in Explaining Underachievement in Education.Azaa RegmiNo ratings yet

- Material Deprivation & Gender Interaction Impact on EducationDocument3 pagesMaterial Deprivation & Gender Interaction Impact on EducationJoyce Ama WilliamsNo ratings yet

- Gender Inequality PDFDocument11 pagesGender Inequality PDFRaiza Basatan CanillasNo ratings yet

- Annotated Bibliography Final DraftDocument9 pagesAnnotated Bibliography Final DraftBlair GibsonNo ratings yet

- Hidden Values Taught in ClassroomsDocument4 pagesHidden Values Taught in ClassroomsMike McDNo ratings yet

- Rsearch Proposal2Document18 pagesRsearch Proposal2Keneleen Camisora Granito LamsinNo ratings yet

- J-Ron O. Valerozo: DirectionsDocument5 pagesJ-Ron O. Valerozo: DirectionsValerozo, J-ron O.No ratings yet

- Deconstructing Power Privilege and SilenDocument18 pagesDeconstructing Power Privilege and SilenPj InudomNo ratings yet

- Yalit Diversity Journal AnnotationDocument5 pagesYalit Diversity Journal Annotationapi-253297734No ratings yet

- Systemic Oppression in Academics: Annotated BibliographyDocument12 pagesSystemic Oppression in Academics: Annotated Bibliographyapi-549071208No ratings yet

- Final EssayDocument9 pagesFinal Essayapi-512886330No ratings yet

- Aiming Higher Together Strategizing Better Educational Outcomes For Boys and Young Men of ColorDocument93 pagesAiming Higher Together Strategizing Better Educational Outcomes For Boys and Young Men of Colorcorey_c_mitchellNo ratings yet

- Education & Research Methods FunctionalismDocument12 pagesEducation & Research Methods Functionalismsairah khanNo ratings yet

- Fragoso Signature Assignment Inner City TeacherDocument15 pagesFragoso Signature Assignment Inner City Teacherapi-490973181No ratings yet

- Thesis Katherine MusialDocument20 pagesThesis Katherine Musialapi-616200298No ratings yet

- Presentation 3Document17 pagesPresentation 3Mousum KabirNo ratings yet

- Pedagogical Conditions For The Formation of Gender Equality Thinking in StudentsDocument4 pagesPedagogical Conditions For The Formation of Gender Equality Thinking in StudentsAcademic JournalNo ratings yet

- Uncertain Beginnings Learning To Teach Paradoxically PDFDocument6 pagesUncertain Beginnings Learning To Teach Paradoxically PDFBrenda Loiacono CabralNo ratings yet

- Ladson Billings CRPDocument8 pagesLadson Billings CRPPaulo TorresNo ratings yet

- Culturally Relevant Teaching in ApplicationDocument13 pagesCulturally Relevant Teaching in Applicationyankumi07100% (1)

- 341 Annotated BibliographyDocument5 pages341 Annotated Bibliographyapi-2689349370% (1)

- Inquiry EssayDocument7 pagesInquiry Essayapi-583843675No ratings yet

- Conflict Theory Theories of EducationDocument3 pagesConflict Theory Theories of EducationRoxanne DoronilaNo ratings yet

- Attitudes Related To Social Studies Among Grade 9 Students of MSU-ILSDocument5 pagesAttitudes Related To Social Studies Among Grade 9 Students of MSU-ILSjean gonzagaNo ratings yet

- PracticingDemocracy Colleagues SU FA13 ArticleDocument8 pagesPracticingDemocracy Colleagues SU FA13 ArticleJoel WestheimerNo ratings yet

- Action Research: Purpose, Problem Statement, Questions and Literature Review Joaquin Torres American College of EducationDocument18 pagesAction Research: Purpose, Problem Statement, Questions and Literature Review Joaquin Torres American College of EducationJoaquin TorresNo ratings yet

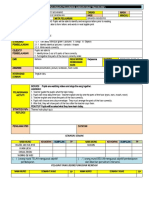

- Rancangan Pelajaran Harian Bagi Tahun 2021: Senarai SemakDocument1 pageRancangan Pelajaran Harian Bagi Tahun 2021: Senarai Semakyankumi07No ratings yet

- Rancangan Pelajaran Harian Bagi Tahun 2021: Theme/ Role Play/ QuizDocument1 pageRancangan Pelajaran Harian Bagi Tahun 2021: Theme/ Role Play/ Quizyankumi07No ratings yet

- CamScanner 11-09-2020 22.10Document1 pageCamScanner 11-09-2020 22.10yankumi07No ratings yet

- RPH Bi Aktif 1Document2 pagesRPH Bi Aktif 1yankumi07No ratings yet

- Rancangan Pelajaran Harian Bagi Tahun 2020: Tugasan/PblDocument1 pageRancangan Pelajaran Harian Bagi Tahun 2020: Tugasan/Pblyankumi07No ratings yet

- RPH Bi Aktif 2Document2 pagesRPH Bi Aktif 2yankumi07No ratings yet

- Rancangan Pelajaran Harian Bagi Tahun 2020: Tugasan/PblDocument1 pageRancangan Pelajaran Harian Bagi Tahun 2020: Tugasan/Pblyankumi07No ratings yet

- Rancangan Pelajaran Harian Bagi Tahun 2020: Tugasan/PblDocument1 pageRancangan Pelajaran Harian Bagi Tahun 2020: Tugasan/Pblyankumi07No ratings yet

- Rancangan Pelajaran Harian Bagi Tahun 2020: Tugasan/PblDocument1 pageRancangan Pelajaran Harian Bagi Tahun 2020: Tugasan/Pblyankumi07No ratings yet

- Rancangan Pelajaran Harian Bagi Tahun 2020: Tugasan/PblDocument1 pageRancangan Pelajaran Harian Bagi Tahun 2020: Tugasan/Pblyankumi07No ratings yet

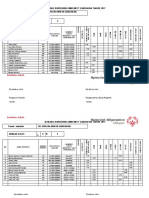

- Borang Divisioning Mini Meet So Sandakan Tahun 2017Document4 pagesBorang Divisioning Mini Meet So Sandakan Tahun 2017yankumi07No ratings yet

- CamScanner 11-09-2020 22.09Document1 pageCamScanner 11-09-2020 22.09yankumi07No ratings yet

- 1Document5 pages1yankumi07No ratings yet

- RPH Bi Aktif 2Document1 pageRPH Bi Aktif 2yankumi07No ratings yet

- Head of FailDocument1 pageHead of Failyankumi07No ratings yet

- GMBR2 Responden1Document7 pagesGMBR2 Responden1yankumi07No ratings yet

- STDocument2 pagesSTyankumi07No ratings yet

- Presentation 1Document6 pagesPresentation 1yankumi07No ratings yet

- Bearmask Brown3 PDFDocument0 pagesBearmask Brown3 PDFyankumi07No ratings yet

- LeadershipDocument37 pagesLeadershipAmmad SheikhNo ratings yet

- Human ResourseDocument10 pagesHuman Resourseyankumi07No ratings yet

- PDF Naesp1746 Whatk8principalsshouldknowabouDocument6 pagesPDF Naesp1746 Whatk8principalsshouldknowabouyankumi07No ratings yet

- Culturally Relevant Teaching in ApplicationDocument13 pagesCulturally Relevant Teaching in Applicationyankumi07100% (1)

- Students Attitudes Towards Science in Classes Using Hand-On Vs TextbooksDocument12 pagesStudents Attitudes Towards Science in Classes Using Hand-On Vs Textbooksyankumi07No ratings yet

- Why Focus On Cultural Competence and Culturally Relevant Pedagogy?Document4 pagesWhy Focus On Cultural Competence and Culturally Relevant Pedagogy?yankumi07No ratings yet

- Adult Learning For OKU PeopleDocument15 pagesAdult Learning For OKU PeopleDieHa ElDhaNo ratings yet

- Episode 3 Makes 3Document1 pageEpisode 3 Makes 3yankumi07No ratings yet

- Rancangan Tahunan Bahasa Inggeris Pendidikan Khas BPDocument12 pagesRancangan Tahunan Bahasa Inggeris Pendidikan Khas BPPURNAMA MERINDUNo ratings yet

- SyntaxDocument2 pagesSyntaxyankumi07No ratings yet

- Oracle Fusion Talent ManagementDocument26 pagesOracle Fusion Talent ManagementmadhulikaNo ratings yet

- Positive Classroom Teylin 2 PaperDocument14 pagesPositive Classroom Teylin 2 PaperRaden Zaeni FikriNo ratings yet

- Winter2023 Psychology 350-102-Ab PastolDocument4 pagesWinter2023 Psychology 350-102-Ab PastolAlex diorNo ratings yet

- Human Resource Development Chapter 4Document25 pagesHuman Resource Development Chapter 4Bilawal Shabbir100% (1)

- Theories of Risk PerceptionDocument21 pagesTheories of Risk PerceptionYUKI KONo ratings yet

- ACCA f1 TrainingDocument10 pagesACCA f1 TrainingCarlene Mohammed-BalirajNo ratings yet

- Modified MLKNN AlgorithmDocument11 pagesModified MLKNN AlgorithmsaurabhNo ratings yet

- Translating Cultures - An Introduction For Translators Interpreters and Mediators David KatanDocument141 pagesTranslating Cultures - An Introduction For Translators Interpreters and Mediators David KatanJeNoc67% (6)

- The Teacher As A Knower of CurriculumDocument38 pagesThe Teacher As A Knower of CurriculumAlyssa AlbertoNo ratings yet

- Machine Learning Systems Design Interview QuestionsDocument22 pagesMachine Learning Systems Design Interview QuestionsMark Fisher100% (2)

- Exploring The Association Between Interoceptive Awareness, Self-Compassion and Emotional Regulation - Erin BarkerDocument73 pagesExploring The Association Between Interoceptive Awareness, Self-Compassion and Emotional Regulation - Erin BarkerNoemi RozsaNo ratings yet

- Simple Past Story 1Document7 pagesSimple Past Story 1Nat ShattNo ratings yet

- Basic English Course Outline - BBADocument7 pagesBasic English Course Outline - BBARaahim NajmiNo ratings yet

- Psych KDocument1 pagePsych KMichael Castro DiazNo ratings yet

- Inter-Professional Practice: REHB 8101 Week 1 Jill GarnerDocument26 pagesInter-Professional Practice: REHB 8101 Week 1 Jill Garnerphuc21295No ratings yet

- Pangasinan State University 2Document4 pagesPangasinan State University 2Emmanuel Jimenez-Bacud, CSE-Professional,BA-MA Pol SciNo ratings yet

- Presentation of OBE To StudentsDocument61 pagesPresentation of OBE To StudentsTayyab AbbasNo ratings yet

- Develop Effective ParagraphsDocument8 pagesDevelop Effective ParagraphsLA Ricanor100% (1)

- HRD Climate SurveyDocument3 pagesHRD Climate SurveySUKUMAR67% (3)

- Komunikasi LisanDocument19 pagesKomunikasi Lisanekin77No ratings yet

- Utilizing Patola Fiber for Paper and Used Paper as InkDocument4 pagesUtilizing Patola Fiber for Paper and Used Paper as InkAlex GarmaNo ratings yet

- DefinitiveStudent Peer Mentoring Policy Post LTC 07.06.17Document4 pagesDefinitiveStudent Peer Mentoring Policy Post LTC 07.06.17Wisdom PhanganNo ratings yet

- M 408D - Calculus II Fall - 2015Document2 pagesM 408D - Calculus II Fall - 2015MikeNo ratings yet

- BUS5003D Enterprise and Entrepreneurship (275) Part 1Document9 pagesBUS5003D Enterprise and Entrepreneurship (275) Part 1Sanjana TasmiaNo ratings yet

- DLP 1 - Math8q4Document3 pagesDLP 1 - Math8q4JOEL ALIÑABONNo ratings yet

- Evidence Based Observation Techniques Requirement 2Document2 pagesEvidence Based Observation Techniques Requirement 2api-340155293No ratings yet

- Engleski SastavDocument3 pagesEngleski Sastavtalija jovanovicNo ratings yet

- 3 Around The WorldDocument15 pages3 Around The WorldAlberto R SánchezNo ratings yet

- Session Plan-5-Clean Public Areas Facilities and EquipmentDocument2 pagesSession Plan-5-Clean Public Areas Facilities and EquipmentScarlette Beauty EnriquezNo ratings yet

- Unit I MACHINE LEARNINGDocument87 pagesUnit I MACHINE LEARNINGapurvaNo ratings yet

- For the Love of Men: From Toxic to a More Mindful MasculinityFrom EverandFor the Love of Men: From Toxic to a More Mindful MasculinityRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (56)

- Summary: Fair Play: A Game-Changing Solution for When You Have Too Much to Do (and More Life to Live) by Eve Rodsky: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedFrom EverandSummary: Fair Play: A Game-Changing Solution for When You Have Too Much to Do (and More Life to Live) by Eve Rodsky: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Uncovering the Logic of English: A Common-Sense Approach to Reading, Spelling, and LiteracyFrom EverandUncovering the Logic of English: A Common-Sense Approach to Reading, Spelling, and LiteracyNo ratings yet

- Unwanted Advances: Sexual Paranoia Comes to CampusFrom EverandUnwanted Advances: Sexual Paranoia Comes to CampusRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (22)

- Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of IdentityFrom EverandGender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of IdentityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (317)

- Feminine Consciousness, Archetypes, and Addiction to PerfectionFrom EverandFeminine Consciousness, Archetypes, and Addiction to PerfectionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (89)

- Never Chase Men Again: 38 Dating Secrets to Get the Guy, Keep Him Interested, and Prevent Dead-End RelationshipsFrom EverandNever Chase Men Again: 38 Dating Secrets to Get the Guy, Keep Him Interested, and Prevent Dead-End RelationshipsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (386)

- The Masonic Myth: Unlocking the Truth About the Symbols, the Secret Rites, and the History of FreemasonryFrom EverandThe Masonic Myth: Unlocking the Truth About the Symbols, the Secret Rites, and the History of FreemasonryRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (14)

- You Can Thrive After Narcissistic Abuse: The #1 System for Recovering from Toxic RelationshipsFrom EverandYou Can Thrive After Narcissistic Abuse: The #1 System for Recovering from Toxic RelationshipsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (16)

- Fearing the Black Body: The Racial Origins of Fat PhobiaFrom EverandFearing the Black Body: The Racial Origins of Fat PhobiaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (112)

- The Read-Aloud Family: Making Meaningful and Lasting Connections with Your KidsFrom EverandThe Read-Aloud Family: Making Meaningful and Lasting Connections with Your KidsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (205)

- Unlikeable Female Characters: The Women Pop Culture Wants You to HateFrom EverandUnlikeable Female Characters: The Women Pop Culture Wants You to HateRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (18)

- Sex and the City and Us: How Four Single Women Changed the Way We Think, Live, and LoveFrom EverandSex and the City and Us: How Four Single Women Changed the Way We Think, Live, and LoveRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (22)

- Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of PlantsFrom EverandBraiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of PlantsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1422)

- Our Hidden Conversations: What Americans Really Think About Race and IdentityFrom EverandOur Hidden Conversations: What Americans Really Think About Race and IdentityRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (4)

- Family Shepherds: Calling and Equipping Men to Lead Their HomesFrom EverandFamily Shepherds: Calling and Equipping Men to Lead Their HomesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (66)

- Liberated Threads: Black Women, Style, and the Global Politics of SoulFrom EverandLiberated Threads: Black Women, Style, and the Global Politics of SoulRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- King, Warrior, Magician, Lover: Rediscovering the Archetypes of the Mature MasculineFrom EverandKing, Warrior, Magician, Lover: Rediscovering the Archetypes of the Mature MasculineRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (65)

- Tears of the Silenced: An Amish True Crime Memoir of Childhood Sexual Abuse, Brutal Betrayal, and Ultimate SurvivalFrom EverandTears of the Silenced: An Amish True Crime Memoir of Childhood Sexual Abuse, Brutal Betrayal, and Ultimate SurvivalRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (136)

- Fed Up: Emotional Labor, Women, and the Way ForwardFrom EverandFed Up: Emotional Labor, Women, and the Way ForwardRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- You're Cute When You're Mad: Simple Steps for Confronting SexismFrom EverandYou're Cute When You're Mad: Simple Steps for Confronting SexismRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (26)

- Becoming Kin: An Indigenous Call to Unforgetting the Past and Reimagining Our FutureFrom EverandBecoming Kin: An Indigenous Call to Unforgetting the Past and Reimagining Our FutureRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (9)

- The Longest Race: Inside the Secret World of Abuse, Doping, and Deception on Nike's Elite Running TeamFrom EverandThe Longest Race: Inside the Secret World of Abuse, Doping, and Deception on Nike's Elite Running TeamRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (58)