Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Rajan

Uploaded by

Tanima KumariCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Rajan

Uploaded by

Tanima KumariCopyright:

Available Formats

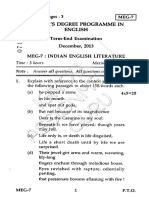

The Feminist Plot and the Nationalist Allegory: Home and World in Two Indian Women's Novels in English

Rajeswari Sunder Rajan

MFS Modern Fiction Studies, Volume 39, Number 1, Spring 1993, pp. 71-92 (Article) Published by The Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: 10.1353/mfs.0.1045

For additional information about this article

http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/mfs/summary/v039/39.1.rajan.html

Access Provided by Indian School Of Mines at 03/08/13 4:04AM GMT

THE FEMINIST PLOT AND THE NATIONALIST ALLEGORY: HOME AND WORLD IN TWO INDIAN WOMEN'S NOVELS IN ENGLISH

mfs

Rajeswari Sunder Rajan

The two novels that form the subject of my essay are Sashi Deshpande's That Long Silence (1988), and Nina Sibal's Yatra (The Journey) (1987), both originally published by British feminist presses. These writers' inscription of space as a gendered concept within

the polarized categories of "home" and "world," provides my point

of entry into the exploration of their novels as representative of a

specific post-independence historical moment. A certain "feminism" and a certain "nationalism," corresponding to the gendered spaces

of "home" and "world," produce the distinctive postcolonial features

of their work.

Some sort of division of private and public spheres seems to have always and universally accompanied the construction of genders, whether, as in classical Tamil poetry, as a division between the spaces of "aham" (inner) and "puram" (outer), corresponding to the polarity love/war; or between leisure and work, as in European eighteenth-century bourgeois society; or between domestic (unpaid) labor and wage labor, or reproduction (child-bearing) and production, as under capitalist social systems. Different kinds of actual (social) values have been attached to each domain, though conceptually the

Modern Fiction Studies, Volume 39, Number 1, Winter 1993. Copyright by Purdue Research Foundation All rights to reproduction in any form reserved.

72

MFS

two have often been treated as equal and complementary. Among women's most common acts of transgression has been the crossing

of boundaries from one sphere of activity to the otherhistorically

this has taken the form of cross-dressing, participation in war, celibacy, religious devotion, adulterous love, seizing the "book" (the

wise woman, the witch), different kinds of work leading to economic independence, etc. But, as my list suggests, some of these transgresse acts may also be absorbed within the social fabric, and

thus become sanctioned acts.

With the emergence of feminist consciousness in nineteenthcentury Europe, the questioning of the very separation of the spheres began. Ibsen's A Doll House (1879), which ends with the female protagonist's exit from the "doll house" that represents femininity, the home, the family, the "private" enclosure, became the most forceful expression of the repudiation of separate spheres. In the colonized countries of Asia, where the women's question was beginning to be articulated in close connection with issues of liberation

and nationalism, A Doll House was popular and widely discussed, as Kumari Jayawardena shows us. Nora's rebellion against male oppression became a symbol of freedom from foreign oppression.

The play was translated into Chinese, and in India Nehru referred to it in a speech to women students in 1928. The freedom of western women became an inspiration to the colonial bourgeois male intent on fashioning the "new woman" for an emergent free nation (Jayawardena 12). In Rabindranath Tagore's novel Ghare Bhaire (The Home and the World) (1919), the question of the two spheres and its imbrication

of the issues of women's freedom and Indian nationalism is explicitly addressed in Indian fiction for the first time. It is not posited as the

female protagonist's choice between two modes of activity, the domestic versus the public; instead the woman becomes the site

of contending ideologies of freedom for both women themselves and

the subject nation. Bimala, the heroine, is perceived by Sandip, the revolutionary, as "Shakti" the goddess, the symbolic "Mother India" of the radical swadeshi movement; and by her husband, Nikhil, the liberal zamindar, as companionate wife on the Western model, and

a partner in the task of economic and social trusteeship. It is only

with her abandonment by the two men who represent these contending forces that Bimala confronts the choice of her future course of action, a choice that lies outside the book. Nevertheless Ghare Bhaire tips the scales in favor of a renegotiation of women's roles within the private sphere. Initially, as

Bimala emerges out of the zenana, the women's enclosure, into the

role of a companionate wifeeducated, liberated, and free to chooseshe finds access to a larger sphere of action, that of

RAJAN

73

participation in the swadeshi movement. But finally, just before the

book ends, when the terrorist leader Sandip has been discredited and is forced to leave her, Bimala turns to her husband in recognition of her "true" option. His death is viewed by her less as a release into a true existential freedom than a form of desertion, the punishment of widowhood.'

Some similar form of re-entry into the domain of familyhowever different the terms of such accommodationappears in books about feminist individualism as different as Charlotte Bronte's Jane Eyre

(1848), and R. K. Narayan's The Dark Room (1938). In both books

brief forays into the outer world are attempted by or offered to the

heroine, only to be rejected by her after experience or consideration; the "proper" place of the woman is the home. The mode of realism,

as Rashmi Bhatnagar has argued, conditions where it does not actually determine the foreclosure of options for the female protagonist (183). Her freedom in any other terms would only be Utopian, therefore ultimately unrealistic. But within the claustrophobia that realism as a novelistic form would seem to engender, these novels also offer avenues of escape for the female protagonist through such creative outlets as fantasy, dreams, writing, journeys, the recognition of a (mad, angry) alter ego,2 which are sanctioned by the form without being entirely subsumed within it. Our judgment of how liberatoryin a feminist sensethese representations of women's transactions between home and world are, will depend on two things: our understanding of their historical location; and our strategic interpretation and deployment, as contemporary feminist readers, of the meaning of their actions. In this essay I attempt to place That Long Silence and Yatra within the broad framework that this problematic suggests. That Long Silence, written as an exercise of memory and catharsis, is the autobiographical narrative of the protagonist Jaya, a middle-class, middle-aged Bombay housewife. Her husband, Mohan, involved in a case of corruption at work, is hiding out with Jaya in a small suburban flat in Bombay. This limbo of waiting and anxiety allows Jaya to reflect on her life and upon her roles as a woman daughter, sister, wife, mother, daughter-in-law, friend, mistress, and writer of genteel "feminine" newspaper pieces. The writing of the novel, which is a mix of memory and current happenings, allows her to break out of "the long silence" wrought by the weight of different repressions. She is now prepared to reevaluate her life. Yatra's protagonist, Krishna, who has a Greek mother, is unable to ascertain whether her "true" (biological) father is her mother's Greek lover or her Punjabi husband. Her skin color is not a reliable indication of her paternity, since it progressively darkens after her birth, changing even more vividly at certain crises in her life. Krishna

74

MFS

walks out of her marriage to Anu, a successful lawyer, unable to bear the tyranny of her father-in-law and his evil friend, Chaman Bajaj. She helps her (Indian) father, Paramjit Singh, when he becomes

embroiled in the criminal activities of saboteurs during India's war

in East Pakistan. This leads her into active political life. She chooses as her sphere of action the preservation of the forest of the Him-

alayan mountains. Her lover, Ranjit Singh, a doctor and underground

activist, encourages her. She is in search of fathers, and, in the process, learns of and identifies with some of her female ancestors, Kailash Kaur, Swaranjit Kaur, Poonam, and others. She emerges as

a leader, a true "Indian." The narrative juxtaposes many time periods

and creates complex connections through different motifs of violence

and evil.

Novels written in English by Indian women and published in the west are neither a recent, nor a unique, literary phenomenon. The reason for my choice of texts is rather to mark what is common to and different between That Long Silence and Yatra, that is, to

homogenize such literary production as well as to insist upon the heterogeneity of the novels' narrative modes, their politics, their

location within the cultural and geographical division of the subcontinent. My primary interest, and even my premise, it must be confessed, is based less upon an aesthetic evaluation of these writers than upon the representativeness, as it has seemed to me,

of their texts.3

Sibal and Deshpande conform to an almost standard profile of

the "Indo-Anglian" woman writer: both are urban, middle-class, educated, professional women (and both have university degrees in

English literature). While Deshpande was born and lives in the south of India (in the state of Karnataka), Sibal's parentage, like her protagonist's, is Punjabi-Greek and, as a career diplomat, her lifestyle is "cosmopolitan." The point about their regional "origins" has some bearing upon their different literary affiliations. I mark other contrasts

between the two writers in a simplified and overt catalogue: the

"space" that Deshpande delineates for her protagonist is the domestic, the social milieu is the family, the narrative mode is social realism; Sibal's protagonist is diasporic, her location is the "nation,"

the novel's narrative mode is that of "marvelous" realism. Issues

of women and the "nation" inevitably inform both works, but the specific forms of the consciousness and politics of feminism and

nationalism vary in the two novels.

Preliminary to this exploration, the broad context within which we may locate both novels would be provided by asking:

In India, today, what does it mean to write, at all?

RAJAN

75

Further, what does it mean to write as a woman? What does it mean to write as a woman, in English?

The answers to these questionseven when severely curtailed by

the limitations of this essaymust nonetheless be attempted. There is, first, the question that essentially asks: what does it mean to be a writer in India? As U. R. Anantha Murthy points out,

this must primarily be treated as a question of literacy in a nation that has one of the highest rates of illiteracy in the world (76-77). The major division in the Indian social structure is not between English-educated and Indian language-educated groups (as political

rhetoric would have us believe), but between the literate few and the illiterate manyor, more specifically, between the educated elite and the uneducated majority; so that any book-reading public is always already an elite, though admittedly not a homogeneous practice. To create "outside" the "defined framework of the cultural

and literary expectations" of this highly limited reading public, Anantha Murthy reflects, a writer would have to resurrect the oral tradition of twelfth-century Bhakthi poetry. But no such responsiveness to this still available tradition is visible in the contemporary writer's agenda (78). It is clear that we cannot talk of any aspect of writing in India without acknowledging the class aspect of written, or recorded,

literary production. The publication of an anthology like the recent

massive two-volume Women Writing in India exemplifies, even as it

acknowledges, all the contradictions of an enterprise that locates gender as the constitutive aspect of writing. Treating women as

definitionally subaltern, and their writing, therefore, as always already

a resistant practice, the anthology's editors view the tasks of feminist

criticism, variously, as those of the retrieval, restoration, translation, and dissemination of women's voices. Butas the gaps and silences

in the anthology so poignantly testifywithin the category "women"

are to be found other womenpeasant, tribal, lower-castewho go virtually unrepresented because they had/have no access to writing.4

In "Can the Subaltern Speak?," Gayatri Spivak defines the subaltern

as one who "cannot speak" (120-130). Refusing this circularity, feminist researchers seek out women's songs and folklore, record their spoken narratives, create spaces for their receptiontasks that are methodologically and politically fraught, even as they are necessary.5 What they force us to recognize is that writing-as-testimony remains a particularly privileged mode of self-representation

for women in India.

Women novelists writing in English in India therefore necessarily inhabit a rarefied realm; but not only are they, paradoxically, highly visiblewe might even say, visible for that very reasonthey are also treated as representative female voices. My attempt is to draw the boundaries within which they create their fictional worlds: in the

76

MFS

case of Sibal and Deshpande, these are defined by the problematic

of "space." The explanation for the divergences in their respective

representations of this conceptual paradigm is to be found in the different implications writing in English has for the woman novelist. To write fiction in English in India today is to write in the shadow

of Salman Rushdie's Midnight's Children (1981). This may be an

arguable proposition,6 but it cannot be denied that the book's enormous critical and popular acclaim, the sheer excitement it generated in literary circles, its creation of an identity and a mission for a post-Independence generation of young middle-class Indians ("midnight's children"), have had a great impact on contemporary Indian

writers in English. At one stroke Rushdie created a literary space

for the English-language writer of the Indian subcontinent, who may now lay claim simultaneously to a national, a "third world," and an

international identity.7 The debate which earlier (in the immediate post-Independence decades) had focused on language as medium of expressionprimarily therefore on the adequacy of the English

language to record an Indian realityhas in recent years shifted to

a question of reception, a fact that suggests that contemporary

writing in English operates within a newly-defined problematic. A whole generation of writers has arrived at a historical self-consciousness achieved precisely as a function of the distance and the

literary affiliations that English createsand which earlier had seemed

so defeatingly alienating. The titles (and sub-titles) of some of these

recent novels are sufficient indication of the seriousness (and sometimes ironic self-mockery) of the "themes" of nationalism and history that are now so happily embraced: Shadow Lines, In an Antique Land, English August: An Indian Story, Trotter-Nama, The Great Indian Novel, Yatra, Raj. If certain women writers have also responded to the pressures

and participated in the conditions of this literary movement/moment, this ought not to be surprising since, after all, they are products of

the same configuration of social circumstances (class, education,

professional affiliations) that has also produced the male writers of their generation.8 While producing "nationalist" narratives, they simultaneously address the "woman question": most often simply by employing the expedient of replacing the male protagonist of the novel by a female. The story of this protagonist is then combined

with the history of the nation in a number of ways suggested by Midnight's Childrensuch as actual cause-and-effect connections

between the individual protagonist's life story and the country's political events, or symbolic parallels between the one and the other,

or coincidences, or the endowment of the protagonist with significant

birth-dates or "magical" physical features. In these respects Mid-

RAJAN

77

night's Children's closest imitation is Sibal's Yatra. But other novelslike Bapsi Sidhwa's Ice-Candy Man (1987), and Bharati Muhkerjee's Jasmine (1989)include some of these elements of a nationalist narrative.9 While the female protagonist's links with the destiny of the nation do of course result in her emergence into the "world" and participation in its activities which make for a certain "liberation," equally they reinforce a kind -of (female) passivity in the face of history's forces (apparent even as the obverse side of the persona even of Saleem Sinai, Midnight's Children's male protagonist).10

But to write self-consciously and programmatically as a woman is to be preoccupied with "feminist" themes centrally, not merely

incidentally. In contemporary fiction in Indian languages such writing

has been concerned largely with representing the restrictions of middle-class women's lives. Sashi Deshpande's address to the "woman question" is informed by the particular variety of polemical bourgeois feminism that characterizes this fiction. Her identification with Indian language fiction is a self-conscious one (rather as in R. K. Narayan's case), and is reflected in other features of her work her choice of the "regional" as the novel's milieu, and her emphasis

on the realistic as its mode of representation. Deshpande's feminism

would seem to require a conscious eschewal of "larger" questions of nationalism, a deliberate refusal to write about a '"Raj to Rajiv'" India (as one reviewer put it).11 At one point in the novel, Jaya, the novel's protagonist, ironically draws attention to the significance of her name (Jaya = victory) and of the date of her birth (1939), and mocks the ambitions for her signaled by this naming of her by her

father. It would seem that the questions of feminism at the present literary historical moment in India can be posed only within the genre

of the realistic novel and in relation to the sphere of the bourgeois

home.

To write as a woman in English and publish in the west is to be additionally conscious of how readership structures the politics

of writing.12 An acute tension is evident between the claims of

"universalism" on the one hand, and "third worldism" on the other.

In Deshpande's novel this tension leads to a focus on "women's issues"implicitly regarded as common to all womeneven as the

writer's consciousness about women's oppression is attributed to

promptings from western feminism. The claims of "global" feminism might bind women writers and readers across cultures; but the politics of a covert orientalism, as Chandra Mohanty has argued, tends to reify the representations of Indian women and their world

into such constructs as the "Third World difference" within western

discourse (335). Thus writing for/under western eyes represents for

78

MFS

the Indian writer the dangers of appropriation and (mis)representation. But when, on the other hand, the writer seeks to erase the "third

world difference" (a difference that is invariably represented as third

world women's greater oppression, and therefore their societies'

inferiority to the first world) by producing "nationalist" narratives,

she transcends gender issues only by reproducing a recognizable "third world" narrative paradigm.13

This dilemma of choice, as I have broadly sketched it, explains

how the problematic of "space" gets defined in the two novels I

examine here. In the rest of this essay I explore how and why the female protagonists of these novels are obliged to choose between the enclosed and diasporic spaces of "home" and "world" respectively, in order to define their politics and their identities.

It is in terms of the fictional constructions of feminist individu-

alism within marriage and family (the "private" sphere), that we must view That Long Silence. Like the novels of the nineteenth-

century English women writers Wollstonecraft and Bront, That Long

Silence is a protest against the limitations of women's lives. Like

Jane Eyre, Jaya survives by strategies of escape and doubling; her cousin Kusum is her "other," the one who serves as her scapegoatvictim by going mad and killing herself. As in Tagore's and Narayan's novels, female rebellion in That Long Silence is ultimately checked

by the fear of being leftabandoned or widowedby the male

partner. As in the other novels women's roles in the family are

revalorized at the end of much questioning: "I realised my awesome

power over him [her husband]. . . . Hadn't I seen that phenomenon, the power of woman, in my own family?" (82). Finally, as in the novels of Virginia Woolf and Anita Desai, feminine and masculine values are sharply disjunct and opposed and, in a spirit closer to Desai's critique of bourgeois marriage than to Woolf's construction of complementarities, the possibilities of communication between husband and wife across this divide are questioned.

The force of Deshpande's indictment of women's lives lies in

the way she is able to universalize their condition, chiefly by drawing similarities among Jaya and a variety of other female figures, in-

cluding characters from Indian history and myth; and among three generations of women in her family (Jaya, her mother, her grandmother); among different classes of women (Jaya, her maid Jeeja);

among different kinds o- women of the same class and generation (Jaya, her cousin Kusum, her widowed neighbor Mukta). So com-

pellingly realistic is this rendering that no Indian woman reader can

read this novel without a steady sympathetic identification and, indeed, frequent shocks of recognition.

RAJAN

79

But in her analysis of her situation, Jaya limits the responsibility of a faceless "society," as well as of a more personalized patriarchy

(father, brothers, husbands, male friend, editor, son), and instead

blames her failures on her own limitations: "With whom shall I be

angry? With myself, of course" (192). She absorbs her male friend Kamath's warning: ". . . beware of this 'women are the victims'

theory of yours. It'll drag you down into a soft, squishy bog of selfpity" (148); and she endorses her maid Jeeja's stoicism, her refusal to complain or blame (51-52). Jaya's lucid self-awareness leads her to balance her self-pity with self-castigation. So acute indeed is the latter that it is hard to think of a female protagonist in recent fiction who dislikes herself more. But more questionable than the evenhanded distribution of blame among both men and women that we find in the book is the premise that women's silence is a result of

the failure of communication between individual men and women,

rather than of the flawed structures of social arrangements. Jaya's abjuring of any connection with a "larger" sphere reflected not merely in her irony about her name, but also in a more complex dissociation from social realitiesis an aspect of this refusal to undertake a radical social critique. Men "naturally" occupy the sphere of work and worldJaya's father was a Gandhian activist, her husband feels the excitement of a growing nation as he goes to work in the burgeoning industrial town of Lohanagar, her brother emigrates to America to make a livingwhile Jaya merely watches from a terrace the mill workers tramp to work every morning or go on strike. Surprisingly Jaya does not even seem to know the details of the "trouble" at her husband's work place except for the fact that it has forced him into hiding.14 What makes Jaya's resolute

"keeping" of her place within the home so unusual is that, given

her historical location as a present-day, urban, educated middleclass Indian woman, there should be so little consideration of several contemporary realities which, while they are not precisely "solutions" to her problem, do impinge upon itsuch as the option of a career, or the knowledge of an actual political women's movement built

precisely upon the very consciousness of oppression that has come

to be hers.

That Long Silence offers itself too easily in terms of a contrast

between a "Western" feminism that raises women's consciousness

about their oppression, and an indigenous culture that designates

their role as solely domestic. The allusion in the novel's title is to a British feminist manifesto quoted in the epigraph (American actress

Elizabeth Robins' speech to the WWSL in 1907): "If I were a man

and cared to know the world I lived in, I almost think it would make me a shade uneasythe weight of that long silence of one-half the

world." The models of female submission invoked in the narrative

80

MFS

are, in contrast, all Indian: Jaya's family's female membersher

mother-in-law who silently beat herself upon her face in despair and

died of a botched abortion, her sister-in-law who died of an untreated tumor, Kusum who threw herself into a well; women in Indian myth

and fablethe prudent female sparrow who let the crow die, Gandhari in the Mahabharata who blindfolded her eyes when her husband went blind, the legendary Sita, Savitri and Draupadi who followed where their husbands led, and female characters in Sanskrit drama

who had to speak in the vernacular Prakrit, "like a baby's lisp." There is no denying that a feminist "consciousness," the political

awareness of women's secondary status, is closely related to the

global women's movement. But the itinerary of the female subject that, in recent Indian history as well as fictional narrative, is typically

traced from the home to the world, even if it is routed back to the home, is in That Long Silence short-circuited. In terms of the actual

Indian social situation, for a woman in Jaya's position to take no cognizance of the world of work, politics, even physical geography is to neglect an important component of the reality of the Indian bourgeois woman's situation. In this respect That Long Silence reproduces the limits of Desai's Cry, the Peacock, an overlooked precursor.15

In spite of a commitment to rendering the social world of contemporary middle-class India "realistically," Deshpande would seem to have reproduced instead the literary conventions of classical Tamil poetry, whose generic division into poems of love and war (aham/

puram) is a gendered opposition. The speakers, though not the writers, of "aham" poetry are invariably women, represented in

situations of dialogue with female confidantes, mothers, foster-moth-

ers, and friends, just as the speakers of "puram" poetry are men. This structural division of experience, according to A. K. Ramanujam, reflects one of the primary cognitive categories of the culture (296). While the women in these poems speak freely of desolation, loneliness, boredom, male perfidy and betrayal, there is no radical freedom of questioning and thus no transgressive value in their complaints. It is in terms of this privatization of the "woman question" that

one must locate the question of women's writing. That Long Silence

is the book that its protagonist Jaya writes to break silence. Only writing can bridge the space between the private and the public spheres. The act of writing, while itself a solitary, private activity, results in the text, the public document. But while the writing that

constitutes the narrative of That Long Silence is thematized within

the book, the writing's transformation into a public/published work

is never explained. Deshpande insistently marks the social obstaclesthe prohibitions imposed by Jaya's husband, her editors' expectations, the exhortations of her "private" reader, Kamaththat

RAJAN

81

prevent Jaya's "true" writing as a woman from finding expression; but she remains silent about the means by which this narrative finally

escaped into the public domain as the novel we read, That Long

Silence. Therefore the polarization of the worlds female/male, home/ world, "domesticity"/work remains in place even after the completion of Jaya's "book." At the end of her story, Jaya chooses to operate within the self-imposed limits of the family, resolving to change her

life by renegotiating the power-relations and improving the interpersonal relationships within it rather than through the instrumentality of her writing ("breaking silence"). Jaya's writing is a function of the heightened consciousness, the education, the leisure and privacy to which her class-position

gives her access to (as in the Tamil poems of the "inner" world). But this same position also inhibits the making public of feminist

self-expression. When Jaya writes a "true" story, her husband protests:

"Jaya how could you, how could you have done it? . . . They will all know now, all those people who read this and know us, they will know that these

two persons are us, they will think I am this kind of a man, they will think I am this man. How can I look anyone in the face again? And you, how could you write these things, how could you write such ugly things, how

will you face people after this?" (143-144).

So Jaya stops writing. Within That Long Silence, Jaya's writing

is primarily represented as an act of self-expression and liberation in so far as it leads to self-knowledge, truth-telling and catharsis,

but it never becomes the communication, the entry into community,

the contribution to a public discourse that its publication has resulted

in its actually being. Routed through the feminist press in Britain, and thus exploiting several resources, such as global distance, the

universality of women's oppression, and the sanctioned space of

self-expression, fiction, That Long Silence returns to readers in India as a breaking of that silence.16

For women's writing in Indian languages lacking this route, the

inhibitions are even more severe. In any case, feminist "domestic realism" in Indian writing at the present juncture seems unlikely to attempt to transgress the structure of separate spheres even where home, marriage, familythe private sphereis perceived as most repressive.

IV

The story of Krishna, the heroine of Yatra, is a linear, progressive one, as it traces her transition from private existence to public activity. Betrayal by her husband leads Krishna to opt for the in-

dependent single woman's life; her search for fathers, following upon

82

MFS

her rejection by Paramjit Singh, pushes her into the embrace (angwaltha) of "Mother India"; the urging of a lover puts her on the road to activism/leadership. Thus she moves at every stage from

personal crisis to public role. While at the end of the book she is temporarily restored to her family, including uncles, brother, and long-lost cousins, reconciled to her father, and reunited with her lover, she is, more significantly, poised for the greater destiny that political leadership promises. Power and femininity, public and private

roles, the nation and the family appear to be the implied options of the latter and the earlier stages, respectively, of a woman's "growth."

But Sibal, clearly, does not wish to "reduce" Krishna's story to

this "feminist" scenario that leads her from home to world as a

consequence of domestic crisis. Instead she attempts to trace the

growth of a "nationalist" consciousness in Krishna's soul; and this

nationalism then serves to explain the growth of the individual female subject. Sibal's recourse to a non-linear, synchronic narrative structure that does not follow Krishna's life in chronological sequence, but recreates it instead by juxtaposing various time-frames (including long sections of "history" in the stories of Krishna's ancestors) is a means to this end. Similarly, by not restricting the explanation for Krishna's search for fathers and for a racial/national identity to a

psychological need, Sibal seeks a means of affirming an "Indian"

selfhood for her heroine by forging a transcendent relationship between the (female) individual subject and the "nation." The attempt to raise a "feminist plot" to a "nationalist allegory" turns out, in the end, to be a costly undertaking. I want to consider here some of the implications of Sibal's nationalist politics and the narrative mode it engenders. First, there is the problematic issue of the postcolonial female subject's actual role in the national arena. Sibal resolves this issue

by representing Krishna as a political leader. While Indian women's

role in nationalist endeavors had been, indeed, a significant feature of pre-lndependence struggles and did result in gains for women in such areas as voting rights, access to education, and a limited participation in political affairs,17 in contemporary India their role in

so called "nationalist" projects, as Kumkum Sangari has pointed

out, is less clearly defined (3-7). Their participation in nation-building activities remains either a class prerogative, or an aspect of the

small but influential political women's movement. While undeniably the role of political leadership for women may be viewed as a feminist achievement, Sibal can represent it as such only by stressing Krishna's "exceptional" individuality and by conceding her class prerogatives.

The typical mode of construction of the "exceptional" individual

is to mark her uniqueness in terms of destiny (election) and choice

RAJAN

83

("merit"). Here Sibal follows the model of Rushdie's Saleem Sinai (the child of midnight) for Krishna, her protagonist. Krishna's destiny is indicated by markers similar to Saleem's remarkable birth and

childhood (compare her fetal, skin-reactive sensitivity). But she also

explicitly chooses a new life as a leader: when she realizes that the generation of freedom-fighters (represented by the old activist, Miss Pratibha Anand), is coming to an end, her lover points outs, "There must be others to take over. People like you, Krishna. There's you.

. . . You can be a leader.'" Krishna feels "a curious lovely hope. It

was the empty drop into freedom" (154). But Krishna's decision to "be" a leader is marked with none of the ironic self-reflexivity or the checks and balances with which Rushdie poises Saleem between his actual significance as symbolic "child" of Independent India (and

therefore the inevitable victim of Indira Gandhi's Emergency) and his delusions of grandeur as a maker of history. Sibal, on the contrary, mystifies the woman as leader, typically by de-gendering and, then,

canonizing her. At the point where the story makes the transition to Krishna's assumption of leadership (Chapter 19), the narrative voice becomes

that of a male journalist, a hero-worshipping camp-follower reporting

on Krishna's "padayatra" (journey on foot). He refers to Krishna as

"Krishna-ji" (the honorific "ji" sticks even at several other points

in the narrative). He writes of her with distant reverence: "I do not really know her views. I can only tell you what I saw and heard as

we went along" (155). In this way the mystique of leadership is

preserved.18 The social acceptance of women leaders in politics and here Indira Gandhi comes most readily to mindseems to require, cognitively, some such transcendence of gendered roles.

It is not that Krishna's effortless rise to leadership is "unrealistic." The succession of women to positions of power is a phe-

nomenon by no means rare in Indian politicsbut it has not signified

the elevated status of women in Indian society. Liberation for Sibal's heroine is therefore understandably achieved without any recourse to "feminism" as such. Her family "connections" (an uncle who is

a member of Parliament), her career and financial independence,

her advanced sexual mores, her effortless (and unexplained) lead-

ership qualities are all attributes and privileges of her class position. Sibal links Krishna to her uncle and father quite explicitly: "What a

family triumvirate of mighty Caesars, set to conquer the world Krishna of the darkening skin, Satinder victim of non-violence, and

the crumbling Brigadier . . . clad in the fires of betrayal!" (193).

Destiny, the assumption of being "elect," patrimony, dynastic succession, power, possession: these characteristics of much post-

Independence political leadership in India (the Nehru family most obviously, but other examples are not lacking) are offered uncritically

84

MFS

in this nationalist allegory as aspects of the female subject's public

self. Krishna's patriotism, in spite of the rhetoric of saintliness and

martyrdom in which her public role is described (compare Mahatma Gandhi), cannot be free of the disturbing hints of power (disguised as love), even of a fascist kind:

Slowly, inch by inch, she was drawing India into her with love. Mother India

for the orphaned girl. Her rights would continue to grow. No point stopping with being Lady of the Manor. One day she might be Woman of the World,

distinctions blurring between country and country, her skin encasing the whole twirling earth in a faint dark film, visible from space-ships and the dulcet eyes of extra-terrestrial beings. (170)

Even her worship of ecology as God, her oneness with mountains and forests, is expressed in frequently reiterated metaphors of possession: " feel at last as if they belong to me. Oh, not exclusively, but they do belong. All of India belongs to me'" (165). Woman triumphs, but only through the rhetoric of nonsense. In yet another attempt to preempt the suggestion of a purely individual itinerary of the female subject from the private to the public sphere, Sibal resorts to allegory. Allegory immediately provides a "higher" reach of meaning to the mundane and the merely social the construction of both "gender" and "nation" are thereby turned

into transcendent events. Allegory is also a coded language that

must be interpreted if its "higher" meaning is to be arrived at. Sibal's use of symbolic, magical devices like the supersensitive skin of the unique protagonist is ubiquitous and contributes to the allegorical level of meaning. The use of allegory also requires that the specific politics of actual and different historical situationsthe British conquest of the Punjab, the Guru-ka-Bagh protest, Partition, the annexation of Kashmir and Hyderabad, the war with Pakistan, the Punjab agitation be merged into a metaphysics of "evil" against which the savior

Krishna may appear as the principle of "good." (This is most explicitly

played out at the novel's end when Krishna unleashes the dogs

against the evil Chaman Bajaj.) Various recurring motifs of evil

the woman with large breasts, Bibi Chinti, the green Matador, the mysterious Chaman Bajajunify the different episodes of betrayal, treachery and death in the narrative. More specifically, allegory

occludes the problematic construction of the postcolonial nationstate.

The reality of the Indian political situation in 1984, riven by

factionalism and demands for secession, makes the "nation"as

a "natural" or viable entityitself problematic. While the Punjab issue forms part of the narrative, it is kept peripheral to Krishna's story. Sibal associates Krishna's political leadership instead with an issue that is at once feminist, nationalistic, global, and even cosmic:

RAJAN

85

the environment. Krishna describes the significance of Ecology (capitalized) thus: '". . . systems gather up and run into the big one, the State, and that goes on, rung by rung. You have the hierarchy of developing and developed countries, and so on, to Ecology. All systems begin and end with Ecology. They used to call it God'"

(137).19

At the macro-level of allegory we find that patriotism too, like Ecology, is to be viewed as a religion:

"If you love a god enough he will belong to you," she said, "and this is the god of Ecology, higher than all the others." Of course she didn't say this in public; she would have been accused of being irreligious, and a leader has to know what to say and how to say it when she speaks to an

audience. (63)

Krishna relates to "India" through states of trance, intuitive understanding, love and enlightenment similar to religious knowledge (advaita, or monism, is one of the strands of mystic realization in

Hinduism). So if at one level she is a savior, saint or martyr (her feet bleed from the padayatra), at another she is the lover/worshipper, in this way becoming both the god Krishna as well as the devotee Mira. The strategies of transcendence of sexual/gendered roles that women bhaktin poets like Mira employed, and the social sanction

that they found for their liberation in this mode, are invoked here

on behalf of the contemporary Indian woman's freedom. And finally, "freedom" for the novel's female protagonist is

achieved by means of the narrative invocation of marvelous realism, a nonmimetic mode freed from the constraints of realistic repre-

sentation of space and time. In Midnight's Children, which serves

as Sibal's novelistic paradigm of the form, this freedom is treated

as a privilege which, like the picaresque hero's, is to a certain extent naturalized by the (male) sex of the protagonist. Sibal appropriates this privilege for her female protagonist whose wanderings, actual (in space) and imaginary (in history), are of epic, mythic and heroic

proportions. The "freedom" is, as I have indicated, one that has

earlier been achieved "realistically" by the heroine as she stages the classic feminist scene of walking out of the home. Sibal then permits her to occupy the stage of the "world"she wanders through the city of Delhi, the mountains of India, the globe itself (at the

opening of the book she has just returned from London).

The other "marvelous" measure of her freedom is her surrogate presence at the events of history, achieved through her identification with her ancestors. I have drawn attention already to her passive,

skin-reactive sensitivity to historical crises; even as a baby in her

mother's womb she had kicked when bad news about the country

was announced. But once she makes the transition to her "active"

86

MFS

role as history-ma/ce/-, she "becomes" all her female ancestors, "a

host of dispossessed women: Sonia, Swaranjit Kaur, her niece Kailash, and the brave Poonam, who was shattered by a grenade. They were women who had pushed against the walls of dispossession.

She recognized her kinship with them" (305). She also "adopts"

and discards various "fathers" beginning with Nehru: What a journey it had been, this collecting of fathers, incorporating them,

until now, with Ranjit her lover. What a distance, from the moment of birth and confusion, the mixing up of fathers. . . . Now Ranjit was all the loves. . . . She drowned in this love. It was releasing her to live as herself, without fathers. (146-147)

In narrative terms we are given large chunks of family history meshed with the history of India (both a family tree, as well as a gloss on historical events, are provided for reference). Like Saleem Sinai, Krishna gains preternatural "knowledge" of her ancestors ("Krishna stretched herself out beside her ancestor, touching him, spreading

over him, covering him like a shawl . . ." [228]). And also like Saleem Sinai, Krishna inherits gifts, and recognizes kinship ties intuitively. Krishna's claim to ancestry is a feminist assertion, just as is her

demand of an actual patrimony (a share of her father's property). But dynastic succession, even when it is claimed by the daughter,

passes through the (Indian) fathers rather than the (Greek) mother(s).20

If traditional domestic or social "realism" colludes with actual

social and historical "reality" in retaining women within the private sphere of home/domesticity, then it would seem that a fantastic or

Utopian imagination must release them into diasporic freedom. Certainly Sibal's appropriation of the thematic of the quest, her employment of magical motifs, the scope of allegory and epic that she invokes, and her breakdown of space/time constraints in imitation of the narrative mode of marvelous realism, are attempts towards

achieving this "freedom" for her heroine. But the leap into fantasy/ utopia must always be, paradoxically, grounded in reality, and when

it is not, the result, as in Yatra, is merely a vague and inflated rhetoric. Yatra, it seems to me, represents the costs of a failed enterprise.

Sibal's transcendence of the private/public polarity on behalf of

a "nationalistic" female subject is as historically invalid as Deshpande's retention of the polarity on behalf of her "domestic" heroine. The realistic and allegorical narrative modes that the two writers employ are complicitous with the specific resolutions of female social/narrative "space" in the two novels. Both the supra-individual,

RAJAN

87

and the individualist, identities which Sibal and Deshpande create,

respectively, for the female subject, fail to come to terms with

women's collective identitya negotiation which it seems to me is called for, not only in political terms, but in terms of a recognition of present historical reality. Within the broad common identity that may be claimed for Sibal and Deshpande as contemporary Indian women novelists in English, both published by British feminist presses almost simultaneously as "representative" Third World feminist writers, there are significant

differences that I have tried to locate and account for. Within a

paradigmatic feminist-nationalist consciousness conceptually translated into a home-world structure, they are able to achieve one only at the expense of the other. There are paradoxes to be discovered

while charting these differences. Deshpande's representation of the

female condition has been acclaimed as both "universal" and "In-

dian" by reviewers in Britain and India respectively;21 her protagonist

is an "everywoman" who is, ironically, both through the autobio-

graphical mode of narration and a sharply self-critical analytic-introspective stance, rendered in terms of a liberal/existential individualism; and while the breaking of her "long silence" is made at one level

through the act of writing itself, at another level it is achieved only through renegotiating interpersonal relations within the family. Sibal's representation of the postcolonial female protagonist with a national

destiny is, in contrast, global when it is not cosmic in dimension; her heroine is unique, elect, a leader; the narrative is rendered in the third person omniscient mode which is uncritical, even hagiographie in tone; and female subjectivity is represented as supra-

individualistic, emptied of personal (gendered) identity, both mystically and politically that of a "leader's." I have tentatively identified Deshpande with regional women writers in Indian languages who represent contemporary middle-class women's situations in terms similar to hers. Her protagonist's "rootedness" in the immediate and extended family, in the provincial small town, in the kinship and other mores of a South Indian family, and her invocation of the generic, structural division of experience from Tamil classical poetry,

provide the "indigenous" fixes of her workeven as the language

she writes in, her place of publication, and her "feminist consciousness" are aspects of an education and, of what we might broadly call a sensibility, that are western. Sibal's alliance with the more cosmopolitan "internationalist" fiction of her (largely) male contempo-

raries, her heroine's divided parentage, her search for roots, her

liberated mode of functioning, and her implicit model in the sixteenth-

century mystic poet Mira, provide the heterogeneous identity-fixes (deracination/tradition) of the typical "midnight's child" of recent Indo-Anglian fiction.

88

MFS

In spite of the favorable critical and popular reception the novels have receivedas much an indication of their conforming to certain expectations about "Indian women's novels" as of literary merit they must be perceived as failed works. If my identification of "failures" and contradictions in these works is at one level a reflection

of political/ideological investments, at another level it is also a judgment of literary achievement. The failure of That Long Silence, in my view, is one of limitation, Yatra's one of inflation. That Long

Silence is the better novel because its controlled ironic tone, the

tough but fluid style, and the spare economy of structure are aspects of a successful realistic mode that does reproduce the "reality" of the women's situations. In Yatra, the pretentious, inflated rhetoric, the political naivete, and the derivative narrative mode do not, finally, seem to be expended upon anything worthwhilethey become attributable, simply, to bad writing. I do not wish to attempt to prophesize the "future" of Indian women's writing in English on the basis of these two novels, but they seem to me to be sufficiently divergent and representative to indicate the chief "types" of possible narrative modes that are likely to be followed in women's fiction. Outside the problematic they define lie of course other possibilities, such as the mode of "revolutionary fantasy" that the Bengali writer, Mahasweta Devi, employs in her story "Bashai Tudu." But for the bourgeois women's novel attempting a home/world resolution for the individual female subject, that option is not yet available.

NOTES

1Satyajit Ray's film version of the novel Ghare Bhaire (1984) makes the death

of Nlikhil and the widowhood of Bimala explicit in the closing scenes and thereby

enforces this view.

2As described in Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar, The Madwoman in the Attic.

3Fredric Jameson has argued (in a different context) that "individual artists

are only interesting if one finds some moment when the system as a whole, or some limit of it, is being touched," an argument I here endorse (Stephanson 50).

4For a more extended discussion, see my review of Volume 1 of the anthology

Women Writing in India.

5An example of such work is to be found in IVe Were Making History: Life

Stories of Women in the Telengana People's Struggle, by members of Stree Shakti

Sanghatana in Hyderabad.

6Vikram Seth's recent novel, A Suitable Boy, for instance, has been praised

precisely for being "old-fashionedly" realistic, in contrast to Rushdie's fabulism, magical realism, allegory, and other postmodernist devices as they are termed. But

to write "unlike Rushdie" is also to be in the shadow of Rushdie. Perhaps the

significant differences between Rushdie and Indian novelists in English may be explored in the differences between his expatriate and their "native" status. The position of expatriate (or more accurately immigrant) writers of Indian origin in the UK is

RAJAN

89

enmeshed with the politics of racism and issues of cultural assimilation and identity in ways that are largely irrelevant for writers who live and work in India. The latter's residence in India, as Ahmad has pointed out, "undoubtedly helps [them] consolidate the claim of representing, indeed embodying, the Indian national experience, for their

readerships here as well as abroad" (126). At the same time, there would be no point in insisting on absolute differences; expatriate Indian writers in the West are not in any case exiles, while resident Indian writers are too cosmopolitan, peripatetic, and circumstantially divorced from "roots" in India to be termed "native" sons and daughters. We may then focus on the implications of the differences between the

cultural hybridity of the Asian immigrant in the west that Rushdie remarks about (27), and the social alienation of the English-speaking Indian in India that is epitomized most successfully in Upamanyu Chatterjee's English August.

7Compare this with the most commonly used appellation, "Commonwealth

writing," to describe writing in English that comes from Britain's former colonies, now members of the Commonwealth: Pakistan, India, Sri Lanka, the Caribbean countries, Canada, etc. For a discussion which severely problematizes the labels "national"

and "third world" as descriptive categories of literatures, see Aijaz Ahmad, "Third

World Literature' and the Nationalist Ideology." "International" is used as a casual descriptive term in reviews to mean "written in English in India and published in the West" in contrast to the earlier meaning of the term, as applied, say, to the novels

of Henry James. Here it refers to writing that consciously addresses audiences beyond national boundaries. According to Kazuo lshiguro: "I am a writer who wishes to write international novels . . . [with] a vision of life that is of importance to people of varied backgrounds around the world . . . [which] reflect a world becoming ever

more internationalised."

8The writers of this generation are bonded in a kind of (predominantly) male

fraternity (replicating a vaguely Bloomsbury ethos), belonging as they do to the same

post-Independence generation, and sharing a similar background of upper-class affluence, public school-elite metropolitan college-foreign university education, and

membership in influential professions like journalism, the civil services or the academy.

It is no mere coincidence that these writers came to prominence at a time when the country's ruling coterie, under Rajiv Gandhi, was similarly constituted. While their

actual political consciousness may be non-existent, or at best naive, their hegemonic

class affiliations give them a stake in the post-Independence political sphere that

cannot be discounted. In contrast, writers in Indian languages are likely to be more

"professional," that is, to make a living solely from their literary work. They are also more often likely to be implicated with literary, cultural and political movements in their states, such as progressive writers' groups, the Dalit protest movement, Dravidian reformism etc., than writers in English who tend to be more individualistic.

9lce-Candy Man records the partition of the Indian sub-continent into two

nations, India and Pakistan, at the time of independence in 1947. The protagonist is a young Parsi girl Lenny, growing up in Lahore whose tenth birthday falls on the

day of Pakistan's independence. Lenny is crippled with polio, a disease for which,

according to the doctor, we must "blame the British! There was no polio in India till they brought it here" (17). Lenny's innocence and knowingness is a commentary

on the absurdity and tragedy of the partition. In Mukherjee's Jasmine the heroine is

caught up in the terrorist activities in Punjab, in which her husband is killed, and she escapes to America. She is a child of "India's near-middle age. British things are gone, and in our village they'd never even arrived" (105-106). Her destiny is passageto move from rural India to rural America through shifting identities: Jyoti JasmineJane. She has a scar on her forehead, which she calls her "third eye": "Enlightenment meant seeing through the third eye and sensing designs in history's muddles. . . . How do I explain my third eye to men who only see an inch-long pale,

puckered scar?" (60).

90

MFS

10Saleem Sinai is castrated by the widow's forces during the Emergency, and

is literally impotent during the writing of the book.

11 Maria Couto in the Times Literary Supplement. 12Published in India, as they are beginning to be, Indian women writers in

English confront the fact of the social privilege signaled by their facility in English

more sharply. See Mrinal Pande's review of a recent anthology of stories written in English by women writers.

13I refer here to Fredric Jameson's contention that "all third-world texts are necessarily . . . allegorical, and in a very specific way: they are to be read as what

I will call national allegories, even when, or perhaps I should say, particularly when their forms develop out of predominantly western machineries of representation, such as the novel" (69). This description has taken on prescriptive status, as Aijaz Ahmad complains.

14Jaya does briefly involve herself in Jeeja's affairs, and uses her (class)

influence to help Jeeja's son get preferential treatment at the hospital where he is

admitted. And in a curious and brief observation, Jaya links the silence of women

with that of the striking workers marching in protest (54).

15In this novel, also one narrated (for the most part) in the first person by the

female protagonist Maya, the wife represents "feminine" values as opposed to the

"masculine" values of her lawyer-husband, Gautama. Hers is the world of middleclass leisure which produces a condition that borders on boredom and futility, as Desai obliquely shows; there is another world, the world not only of her husband but of nis family, his mother, sisters, father, merely hinted at, which engages with the "realities" of work, poverty, and politics. Desai offers no explanation, in terms of

gender, why Maya cannot participate in this world; the reason foi her physical

confinement within the home, her emotional retardation, and her intellectual limitations is instead proffered at a reductive psychological level in terms of her sheltered childhood, her father-fixation, and the trauma of a childhood prophecy. While there is a fine ambivalence about the ending of the bookdid Maya actually kill her husband, or does she only imagine herself responsible for his death''the ending in madness reduces considerably the force of the novel's critique of bourgeois marriage.

16The recent publishing history of the book reflects this in a revealing way.

Following its success in the Virago edition, Penguin India republished That Long

Silence in 1989.

17See Jayawardena, especially Chapter 6. 18The omniscient narrator does take a hand, occasionally, to retain the "human,"

even gendered (and sexual) dimensions of her heroine, hinting for instance at secret sexual liasons, or, at a deeper level of bathos, at ordinary hunger: "She longed for

a pakora" (63).

l9More recently, another woman politician, and a GandhiManeka, daughterin-law of Indira Gandhiwon an election on an environment platform, and was made a minister in the ruling government, proving that it can be a successful political

issue.

20Although both Greece and India are identified as Krishna's double inheritance,

from mother and father"From what bastard lineage, from Alexander the Great to

the Pathans of Kohat and refugees of Sialkot, to green-eyed, wandering children, had [the child] come, creating itself even before it was born?" (25)we hear nothing

further in the narrative about Alexander the Great.

21See, for instance, the review in the British weekly, The Sunday Times which

remarks, "Although the book is set in India, ... a universal theme soon emerges

the frustrations of the traditional women's role." Shama Futehally in a review in the

Indian newspaper weekly, Express Magazine , praises, on the other hand, Deshpande's "Indian mode of writing," and her successful exploration of "the physical and mental landscape of the educated Indian woman" (emphasis added).

RAJAN

91

WORKS CITED

Ahmad, Aijaz. "Third World Literature' and the Nationalist Ideology." Journal of Arts and Ideas 17-18 (1989): 117-136. Anantha Murthy, U. R. "The Search for an Identity': A Kannada Writer's Viewpoint." Dialogue: New Cultural Identities. Ed. Guy Amirthanayagam. London: Macmillan, 1982. Bhatnagar, Rashmi. "Genre and Gender: A Reading of Tagore's The Broken Nest and R. K. Narayan's The Dark Room." Woman/Image/Text. Ed. Lola Chatterjee. New Dehli: Trianka, 1986. Brandmark, Wendy. "Kazuo lshiguro." Contemporary Writers. London: Book Trust, 1988. Chaterjee, Upamanya. English August: An Indian Story. London: Faber, 1988. Couto, Maria. Times Literary Supplement, 1 April 1988. Deshpande, Sashi. That Long Silence. London: Virago P, 1986. Devi, Mahasweta. Bashai Tudu. Trans. Samik Bandyopadhyay and Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak. Calcutta: Thema, 1990.

Futehally, Shama. "Mindscapes." Rev. of That Long Silence, by Sashi Deshpande. Express Magazine 20 August 1989. Gilbert, Sandra and Susan Gubar. The Madwoman in the Attic. New Haven:

Yale UP, 1979.

Jameson, Fredric. "Third-World Literature in the Era of Multinational Capital." Social Text 15 (1986): 65-88. Jayawardena, Kumari. Feminism and Nationalism in the Third World. London: Zed Books; New Dehli: Kali for Women, 1986. Mohanty, Chandra Talpade. "Under Western Eyes." Boundary 2 11.3 (1984):

333-358.

Mukherjee, Bharati. Jasmine. New Dehli: Viking, 1990. Pande, Mrinal. "Fourteen Stories in Search of Answers." Rev. of In Other Words: New Writing by Indian Women, ed. Urvashi Butalia and Rita Menon. Book Review XVI, 6, Nov.-Dec. 1992: 17-18. Ramanujam, A. K. Afterword to Poems of Love and War. Dehli: Oxford UP,

1985.

Rushdie, Salman. "Not Guilty!" The Independent on Sunday. Rpt. in Sunday 18-24 February, 1990: 27-32. Sangari, Kumkum. "IntroductionRepresentations in History." Journal of Arts and Ideas 17-18 (1989): 3-7. Seth, Vikram. A Suitable Boy. New Delhi: Penguin India, 1993. Sibal, Nina. Yatra (The Journey). London: The Women's P, 1987. Sidwa, Bapsi. Ice-Candy Man. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1989.

Spivak, Gyatri Chakrovorty. "Can the Subaltern Speak? Speculations on Widow-Sacrifice." Wedge Winter/Spring (1985): 120-130.

Stephanson, Anders. "Regarding PostmodernismA Conversation with

Fredric Jameson." Social Text 17 (1987): 29-54. Sunder Rajan, Rajeswari. "An Exhilarating Anthology." Rev. of Women

Writing in India, Vol. 1. Eds. Susie Tharu and K. Lalitha. Book Review XVI, May-June (1992): 16-17.

Tharu, Susie and K. Lalitha, eds. Women Writing In India, Vol. 1. Delhi:

Oxford UP, 1991.

92

MFS

Rev. of That Long Silence by Sashi Deshpande. The Sunday Times. 27

March 1988: G6b.

IVe Were Making History, Life Stories of Women in the Telengana People's Struggle, by members of Stree Shakti Sanghatana in Hyderabad. New

Delhi: Kali for Women, 1989.

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Salman Rushdie Midnight's ChildrenDocument5 pagesSalman Rushdie Midnight's ChildrenValentina Prepaskovska100% (3)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Hybridity in Midnight's ChildrenDocument43 pagesHybridity in Midnight's ChildrenwafaNo ratings yet

- Salman Rushdie-Imaginary Homelands-Random House Publishers India Pvt. Ltd. (2010)Document424 pagesSalman Rushdie-Imaginary Homelands-Random House Publishers India Pvt. Ltd. (2010)Anca Iordache100% (7)

- Majed (1) Master Thesis Islam and Muslim Identities in Four Contemporary British NovelsDocument251 pagesMajed (1) Master Thesis Islam and Muslim Identities in Four Contemporary British NovelsHalil ÖzdemirNo ratings yet

- 09 - Chapter 3 PDFDocument44 pages09 - Chapter 3 PDFshivamNo ratings yet

- Easy Look on Teaching Commerce Education ApproachesDocument15 pagesEasy Look on Teaching Commerce Education ApproachesTanima KumariNo ratings yet

- Commerce Education - Theoretical Based of Constructivism and BehaviorismDocument6 pagesCommerce Education - Theoretical Based of Constructivism and BehaviorismTanima KumariNo ratings yet

- ApplDocument2 pagesApplTanima KumariNo ratings yet

- Listening SkillsDocument6 pagesListening SkillsTanima KumariNo ratings yet

- Banking Questions For PostDocument16 pagesBanking Questions For PostTarget BankNo ratings yet

- Speaking SkillsDocument7 pagesSpeaking SkillsTanima KumariNo ratings yet

- List of Indian Banks Headquarter & TaglinesDocument8 pagesList of Indian Banks Headquarter & TaglinesTanima KumariNo ratings yet

- ARICON Feb 2020 Oxford Conference Tracks: Education & LiteratureDocument6 pagesARICON Feb 2020 Oxford Conference Tracks: Education & LiteratureTanima KumariNo ratings yet

- Speaking SkillsDocument7 pagesSpeaking SkillsTanima KumariNo ratings yet

- Speaking SkillsDocument7 pagesSpeaking SkillsTanima KumariNo ratings yet

- Play PDFDocument3 pagesPlay PDFTanima KumariNo ratings yet

- 1 ActivityDocument1 page1 ActivityTanima KumariNo ratings yet

- Play PDFDocument3 pagesPlay PDFTanima KumariNo ratings yet

- Diplom KaDocument103 pagesDiplom KaTanima KumariNo ratings yet

- Negotiating DifferentDocument5 pagesNegotiating DifferentTanima KumariNo ratings yet

- Black SexualityDocument8 pagesBlack SexualityTanima KumariNo ratings yet

- The Dark AbodeDocument186 pagesThe Dark AbodeSarojini Sahoo100% (2)

- Midnight's ChildrenDocument1 pageMidnight's ChildrenEmilyClarke100% (1)

- Imaginary HomelandsDocument2 pagesImaginary HomelandsmarathvadasandeshNo ratings yet

- Imaginary Homelands Salman RushdieDocument7 pagesImaginary Homelands Salman Rushdierazataizi444No ratings yet

- Rewriting History Through: Midnight's ChildrenDocument5 pagesRewriting History Through: Midnight's ChildrenAmbily RavindranNo ratings yet

- Midnight's ChildrenDocument4 pagesMidnight's ChildrenLohita RBNo ratings yet

- 0013 Extended Essay M20Document17 pages0013 Extended Essay M20milaperez21No ratings yet

- Salman Rushdie BiographyDocument9 pagesSalman Rushdie BiographyMaría GrilloNo ratings yet

- Essential Books to Read Before Turning 30Document24 pagesEssential Books to Read Before Turning 30eklavya koshtaNo ratings yet

- PHD Thesis On Salman RushdieDocument8 pagesPHD Thesis On Salman Rushdiekelleyhunterlasvegas100% (2)

- Types of English NovelDocument12 pagesTypes of English NovelinfalliblesNo ratings yet

- From Imaginary HomelandsDocument10 pagesFrom Imaginary Homelandsapi-265632286No ratings yet

- Imaginary Homelands. Essays Criticism 1981-1991 (Salman Rushdie) (Z-Library)Document400 pagesImaginary Homelands. Essays Criticism 1981-1991 (Salman Rushdie) (Z-Library)আনাস আহমাদ রাফিNo ratings yet

- English Novel Since 1950Document13 pagesEnglish Novel Since 1950Andrew YanNo ratings yet

- Read 30 Books Before 30Document18 pagesRead 30 Books Before 30KumarNo ratings yet

- The Shadow Lines Additional NotesDocument39 pagesThe Shadow Lines Additional NotesShahruk Khan100% (1)

- Salman Rushdie and Visual Culture Celebr PDFDocument242 pagesSalman Rushdie and Visual Culture Celebr PDFTanya SinghNo ratings yet

- Midnight's Children LPA #2Document11 pagesMidnight's Children LPA #2midnightschildren403No ratings yet

- Midnight's Children - Book OneDocument6 pagesMidnight's Children - Book OneMelissa PorterNo ratings yet

- Time: 3 Hours Maximum Marks: 100 Note: Answer All Questions. All Questions Carry Equal MarksDocument57 pagesTime: 3 Hours Maximum Marks: 100 Note: Answer All Questions. All Questions Carry Equal MarksAmbarNo ratings yet

- INDIAN WRITING IN ENGLISH-Section C & D-Complete PDFDocument120 pagesINDIAN WRITING IN ENGLISH-Section C & D-Complete PDFNarges KazemiNo ratings yet

- Salman Rushdie: Reading The Postcolonial Texts in The Era of EmpireDocument14 pagesSalman Rushdie: Reading The Postcolonial Texts in The Era of EmpireMasood Ashraf RajaNo ratings yet

- Indian English Fiction After 1980Document47 pagesIndian English Fiction After 1980Surajit MondalNo ratings yet

- MCC1Document20 pagesMCC1Victoria CortêsNo ratings yet

- Domesticity in Magical-Realist Postcolonial Fiction by Sara UpstoneDocument26 pagesDomesticity in Magical-Realist Postcolonial Fiction by Sara UpstonemaayeraNo ratings yet

- Midnights Children LitChartDocument104 pagesMidnights Children LitChartnimishaNo ratings yet