Professional Documents

Culture Documents

India Labor Market White Paper

Uploaded by

hanilOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

India Labor Market White Paper

Uploaded by

hanilCopyright:

Available Formats

INDIA’S LABOR MARKET

Case

For

Temporary Staffing Reform

To reduce

Unemployment

A

White Paper

By

Teamlease Services

www.teamlease.com This white paper is a confidential document of

Teamlease Services prepared for private

circulation. No part should be reproduced

without permission and/or acknowledgement

Teamlease White Paper 1

Confidential – for private circulation

SUMMARY

• INDIA’S LABOR MARKET

o Labor force participation is a low 400 million of a 1 billion population

o Organized employment has been stagnant at 30 million for thirty years (22

million in public sector, 8 million in private sector)

o Unorganized employment is the bulk of the labor force (340 million)

o Given that 269 million people are below the poverty line, even the majority

of those employed can barely sustain themselves

o Given India’s employment elasticity (0.15) and ICOR (3.75), the 8 million

new jobs needed to freeze unemployment require an impossible annual

GDP growth rate of 13.6% and investments of $125 billion

• LABOR REFORM BACKGROUND

o Labor laws are a prisoner of a vocal minority of organized labor (mostly

not poor, middle-aged, men) against the majority (poor, low skilled,

women, self-employed, young and unemployed)

o Unorganized employment is exploding with its low productivity, investment

and lack of labor law enforcement

o Unemployment, at 30 million, is more than organized employment

o Jobless economic growth since 1990 has weakened grassroots social

and political support for economic reforms

• CASE FOR LABOR REFORM

o The coming unemployment explosion

o India’s labor environment

o Global trends in work

• CASE FOR TEMPORARY STAFFING

o Temp jobs form up to 10% of employment in some countries

o Ineffective public sector matching (of the 40 million people registered with

employment exchanges in 2004 only 100,030 got jobs)

o Globally 40% of temps find permanent jobs within one year

o The International Labor Organization reversed its fifty-year-old position

opposing temporary staffing in 1997 (Convention 181)

o Temporary staffing accounted for 50% of the reduction in US

unemployment and 11% of job creation in the EU in the 1990s

o A study of US firms found that earnings, margins and stock returns

improved with the increased use of temporary staffing

o Temping gives outsiders (women, young, old, lower skilled, lower

educated, poor, and unemployed, etc) access to labor markets.

• JOB POTENTIAL

o A survey finds that reform to the Indian Contract Labor Act could create

an additional 12 million temp jobs in five years.

Teamlease White Paper 2

Confidential – for private circulation

India’s Labor Market

Population

1 billion

Labor Force

400-420 million

Agriculture 60%

Manufacturing 13%

Construction 5%

Services 24%

ELASTICITY

Agriculture 5% Agriculture 0

Manufacturing 26% Organized Employment Manufacturing 0.26

Construction 4% 30-50 million Construction 1

Services 59% Services 0.57

Overall 0.15

Low or no labor law enforcement

Agriculture, Construction, Unorganized Employment Low productivity

Retailing 340-360 million Low wages

Low Skills

Not literate 0.2%

Age 15-30 12.1%

Literate upto primary 1.2% Unemployed

Female 10%

Middle 3.3% 30-50 million

Men 7.2%

Graduate and above 8.8%

0.01% of employment relative to Temporary Staffing Largely Sales, Technology,

10% in some countries 0.08 million Admin, HR

Teamlease White Paper 3

Confidential – for private circulation

India's

Labor Market

Policy Regulatory

Issues Issues

UNEMPLOYMENT

30 milion officially,more than organized employment Industrial Relations Framework

and growing rapidly

POVERTY REDUCTION

Given 269 million below the poverty line, even Wage determination Framework

employed barely sustain themselves

PUBLIC VS. PRIVATE SECTOR

The organized private sector is only 3% of Job Security provisions

employment

ORGANIZED VS. UNORGANIZED SECTOR

Small Organized (large scale) with low employment Working condition provisions

and large unorganized (small scale) with low capital

AGRI. VS. MANUFACTURING VS. SERVICES

Negative elasticity of agriculture and labor saving Mandatory Payroll Deductions

bias of manufacturing

OUTSIDER ACCESS

Bias against outsiders (poor, low skilled, women, Education and Skill development

and young) by insiders (not poor, middle-aged, men)

RURAL VS. URBAN SECTOR

Rural job growth 25% of urban and fallen more than Gender Issues

half since 1980

REGULATION VS. SUPERVISION

Reverse current over-regulation and Lack of ability to afford broad social security

under-supervision

CREATING VS. PRESERVING JOBS

Temporary vs. Permanent

Shift from employment to employability

COSTS/ ENFORCEABILITY

End legislating ahead of enforcement capacity and Demographics

payment capability

SKILL DEVELOPMENT

44% of labor force is illiterate and only 5% estimated Equity-Growth trade-off

to have vocational skills

Teamlease White Paper 4

Confidential – for private circulation

Case for

Labor Reform

Coming Unemployment India's Global trends in

explosion Labor environment work

Low Employment Elasticity Changed Role of Changing worker

of GDP Government expectations

Unorganized employment Organizational and Supply

Demographics; growing youth

explosion chain deconstruction

End of public sector Internal & External

Intellectuallization

job machine Competition

Negative employment elasticity of Rising female workforce

Offshore markets/ FDI

agriculture participation

Labor saving bias of

Nature of job opportunities Internationalization

manufacturing

Inability to afford Effective & Incentivized

Flexible work structures

social security HR industry

Low Skill levels China's reform Role of Employer

Teamlease White Paper 5

Confidential – for private circulation

Case for

Temporary Staffing

Public Policy Employer Employee

Perspective Perspective Perspective

Just in time labor; handling Keep in touch with the

Unemployment Reduction

fluctuating demand job market

Auditioning permanent Springboard to permanent

Outsider Access

candidates employment

Limited Permanent job Improved employability; skill

Improved Competitiveness

substitution development and experience

Liquidity provider; Better matching

Strategic Flexibility Lifestyle choice

of demand and supply

Differential pay for

Stepping Stone role Supplemental income

special skills

Economic Value and Matching expertise and

Employer Access

job creation Diversity Access

Handling planned and

Competitive economy Training

unplanned absences

Teamlease White Paper 6

Confidential – for private circulation

Recommendations

for

Temporary Staffing Reform in India

Issue Consequence Recommendation

Increased outsourcing to the Amend Section 2(g), 7 of CLRA

unorganized sector

Definition of Principal

Recognize Contract Staffing

Employer Lower job creation Companies as the principal

employer

Contract rotation

Outlocation

Amend Section 10 of CLRA

Sham consulting Amend Sec 25B of IDA

Core, Perenial, industry, timing agreements

and location restrictions Allow contract/ temporary staffing

Barriers for first-time job seekers in all durations, functions and

and labor markets outsiders industries

Amend Sec 15 of MWA

Minimum wage rules Lack of part-time work

for part-time work options Allow pro-rata salary payments

under the Minimum Wages Act

Amend Section 7,12 of CLRA

Over-regulation and under-

Compliance philosophy &

supervision, enforcement Create national licensing for

decentrallization

consistency, transparency, costs contract staffing and move away

from contract-by-contract

Amend EPFO Act

ESI Act

High Mandatory Payroll Evasion, Unorganized job

Deductions creation, employee losses Only after 6 months, 18 months

for employees with salary greater

than Rs 6500 p.m.

Teamlease White Paper 7

Confidential – for private circulation

Table of Contents

Page No.

1. Preface 11

2. The Case for Labor Reform

a. The coming unemployment explosion 14

b. India’s employment environment 15

c. Global trends in work 16

3. India’s Labor Market

a. Policy/ Regulatory Listing 18

b. Historical Perspective – Three eras 20

c. Key Issues 21

4. The Case for Temporary Staffing in India

a. Public policy perspective 24

b. Employers perspective 26

c. Employees perspective 27

5. The Temporary Staffing Industry

a. Background 29

b. Global markets 33

c. Geo-Historic evolution 37

d. Global regulation 38

e. Negative Perception vs. Reality 41

6. Results of Temporary Staffing Survey 42

7. Recommendations for Temporary Staffing Reform in India 45

8. Annexures

a. Indian Labor Market – Facts 52

b. Indian Labor Laws 60

c. Previous Indian Labor reform proposals 73

d. Labor Reform in China 79

e. Labor Reform in other Asian countries 97

f. Bibliography 111

g. About Teamlease 119

Teamlease White Paper 8

Confidential – for private circulation

PREFACE

India’s economic reforms are on track and she has a new appointment to meet a heavily

delayed “tryst with destiny”. However, there is justifiable disappointment with the lack of

new job creation or shift from unorganized employment since reforms began in 1991.

Labor reforms are controversial but equating them with firing workers is wrong. The

much debated exit policy should be forgotten for now in the interest of moving forward;

increment al steps are better than no progress.

We need a “thought world” shift from employment to employability; from preserving jobs

to creating them and from giving fish to teaching how to fish. This white paper is our

attempt to create background for a debate on one of the many possible solutions to

unemployment; temporary staffing.

While a permanent, full-time job may still be the norm, labor markets are changing. The

job-for-life is being replaced with life-long learning, multi-skilling, and a working life with

multiple careers and flexible hours.

However, for a significant part of public opinion and policy makers, temporary staffing

still has the negative connotations of precarious employment. But there is another side of

the coin, namely the positive dimensions of flexibility; outsider access, lower

unemployment, greater employability, and increased labor mobility.

Current temporary staffing laws in India, as with broader labor legislation, favors a vocal

minority (largely not poor, middle-aged men in org anized labor) against the majority

(young, old, poor, lower skilled, women, unemployed, unorganized, and self-employed).

This is unfair and needs to change.

We make the case that temporary staffing companies address the flexibility needs of

workers and companies, and create jobs. In this way, staffing companies build stronger

societies.

India’s progress will not be worth the trip if we do not give a majority of our people the

strength and self- esteem that comes with a job. Let the journey begin.

The Team lease Team

Teamlease White Paper 9

Confidential – for private circulation

CHAPTER 2: THE CASE FOR LABOR R EFORM

India’s economic reforms have produced results but the jobless growth of the 1990s

needs to change; the case for deeper labor reform can be built on three grounds:

Case for

Labor Reform

Coming Unemployment India's Global trends in

explosion Labor environment work

Low Employment Elasticity Changed Role of Changing worker

of GDP Government expectations

Unorganized employment Organizational and Supply

Demographics; growing youth

explosion chain deconstruction

End of public sector Internal & External

Intellectuallization

job machine Competition

Negative employment elasticity of Rising female workforce

Offshore markets/ FDI

agriculture participation

Labor saving bias of

Nature of job opportunities Internationalization

manufacturing

Inability to afford Effective & Incentivized

Flexible work structures

social security HR industry

Low Skill levels China's reform Role of Employer

Teamlease White Paper 10

Confidential – for private circulation

The coming unemployment explosion

1. Low employment elasticity of GDP India’s labor force growth of 2% a

year needs 8 million new jobs just to keep unemployment frozen where it is. With an

employment elasticity of GDP of 0.15 and an Incremental Capital output Ratio

(ICOR) of 3.75, 8 million jobs need a sustained GDP growth of 13.6% and

investments of $125 billion. These numbers are practically impossible and we will not

have massive job creation unless we raise our employment elasticity of GDP.

2. Demographics; growing youth India is the only country in the world growing

younger and more than 60% of our unemployed are youth. Current labor laws are

biased against first -time job seekers and we will have a social catastrophe if the

youth are not channelized into productive and self-esteem creating employment.

3. End of public sector job machine Public sector employment forms the majority

of organized, formal employment. However, with an informal freeze or heavy slow

down on recruiting and a tight fiscal situation, this sector is shrinking. Reinforced by

privatization of PSUs, deregulation of government monopolies and overall

liberalization, this sector cannot drive job growth.

4. Negative employment elasticity of agriculture The employment elasticity of

GDP for agriculture is negative i.e. we could increase production by reducing the

number of people employed. This represents massive underemployment due to the

lack of alternative in rural areas and is not expected to change soon.

5. Labor saving bias of manufacturing The expectations of huge job

creation from manufacturing are at odds with the labor saving bias and capital

intensity of manufacturing of the last few years. For e.g. Bajaj Auto produced 2.4

million vehicles last year with 10,500 workers; in the early 90s they made 1 million

vehicles with 24,000 workers. Also Tata motors made 311,500 vehicles with 21,000

workers in 2004; in 1999 it made 129,400 vehicles with 35,000 workers.

6. Inability to afford social security There are no formal social security benefits

and India’s demographics and fiscal situation will not allow them in the future (even

paying 26% of the population below the poverty line a social security benefit equaling

50% of the per capital income would need 13% of GDP; close to total tax receipts).

The best and only viable social security is massive job creation.

7. Low skill Levels The percentage of the Indian labor force with skills/

vocational training is among the lowest in the world at 5.06%. Poor skills reduce

worker productivity and also makes them less likely to fit into the service/ knowledge

economy. More than 40% of the labor force is illiterate and only 5% are estimated to

have the vocational skills for credible employment.

Teamlease White Paper 11

Confidential – for private circulation

India’s employment environment

1. Changed role of government India’s labor laws were written after independence

with the philosophy of state domination in business and legislation. The process

begun in 1990 of deregulation, privatization and liberalization has changed the

economic and financial landscape but the assumptions underlying the labor

regulatory regime have not been updated.

2. Unorganized employment explosion Unorganized employment is to be 93% of

workforce. The explosion of the unorganized sector is largely to avoid irrational labor

legislation but comes at the expense of benefits of the formal economy; credit

access, training, benefits, etc. From a public policy perspective, the formal sector is

more desirable because it offers better working conditions, improves employability,

pays taxes and has higher productivity.

3. Internal and External competition Indian industry grew up in a protected

environment but global competition and technological uncertainty have changed their

habitat. Companies must respond quickly when new products are launched, new

technologies are assimilated, new competitors emerge and old ones die, prices of

products fall, cost of input materials rise, interest rates and exchange rates fluctuate,

and so on. Companies need flexibility to handle all this change; the end of textile

quotas creates a unique need for labor flexibility for Indian companies.

4. Offshore Markets/ FDI India has become an offshore services hub and is showing

increased prowess as a manufacturing base. The globalization of supply chains and

increased foreign investment offers a unique opportunity for India but needs an

enabling environment of relevant and flexible labor regulations.

5. Nature of job opportunities India’s labor laws have been written for a time when

agriculture and manufacturing were the main sectors of the economy. Furthermore,

the off shoring revolution had not yet begun. A majority of new jobs in the next

decade will be entry-level jobs in service and manufacturing. This fits well with our

young population but current labor laws are stacked against first time job seekers.

6. Effective and incentivized HR industry An increase in HR firms has led to

improved demand and supply matching in India’s labor markets. Their efficiency will

only increase as global majors enter the country and raise competition. Temp staffing

companies are particularly economically incentivized to keep people at work since

any gap or delays in matching candidates and jobs represents losses.

7. China ’s reform China has modified its labor laws to create an exceptional

environment for investment and job creation. It is our biggest competitor for jobs

arising out of global FDI and the globalization of supply chains ; we need to worry

about our relative attractiveness which seems to have weakened. This is particularly

relevant in labor intensive industries like toys, textiles, machine tools and many more.

Teamlease White Paper 12

Confidential – for private circulation

Global trends in work

1. Changing worker expectations A study by Spherion Corp identified what it

calls the “emergent workforce”, workers who need to feel more in control of their

careers and want an employer who rewards them based on performance, versus

“traditional” workers who believe that an employer is responsible for providing a clear

career path and in return deserves an employee’s long-term commitment. Emergent

workers are more concerned about opportunities for mentoring and growth and are

less focused on the traditional arrangements of job security, stability and tenure.

2. Organizational and supply chain deconstruction The traditional boundaries of

a company are being redefined by technology but the driving forces are strategy and

focus. Charles Handy talks about the “shamrock organization” where the core

structure of expertise consists of essential managers, technicians, and professionals

forming the nerve center of the organization. Embodied in this first leaf are the

organization’s culture, its knowledge and direction. The second leaf of the shamrock

comprises the non-essential work that may be farmed out to contractors. The third

leaf is the flexible workforce; temporary and part-time workers who can be called on

to meet fluctuating demands for labor.

3. Intellectualization Globally, regardless of labor force composition by age or

gender, the chance of finding a job rise with education. The underlying forces include

a decline for unskilled and semi-skilled labor driven by technological innovations that

greatly increase the productivity of skilled workers. Further, the transition to a service

economy demands higher socials skills and accelerates skill obsolescence.

4. Rising female workforce participation The huge entry of women into the

workforce, particularly married women with children is a major driver towards more

flexible labor markets. The huge participation dip by women when families were

formed (the children break) around age 30 is no longer significant. The labor force is

in transition from a uniform male breadwinner society towards a multiplicity of

household working arrangements.

5. Internationalization Labor markets are globalizing in two ways; labor mobility

(physical movement of people) and job mobility (offshore manufacturing and service

delivery). Given the demographics and cost structures of developed countries, this

may accelerate but specifics will depend upon politics and non-economic factors.

6. Flexible work structures Many work relationships are different from the

standard; a full time job (38-40 hours a week) with a permanent, open-ended

contract with an employer. New forms of labor demand and supply have emerged as

a consequence of the changing and more heterogeneous preferences of both

employers and employees. There is more frequent use of self- employment, part -time

work, limited duration contracts and temporary staffing.

7. Role of Employer Employers are no longer viewed as paternalistic providers

of lifetime employment and benefits. This has also led to the monetization of benefits

and a move to CTC (Cost-t o-Company) in compensation.

Teamlease White Paper 13

Confidential – for private circulation

CHAPTER 3: INDIA’S LABOR MARKET

Population

1 billion

Labor Force

400-420 million

Agriculture 60%

Manufacturing 13%

Construction 5%

Services 24%

ELASTICITY

Agriculture 5% Agriculture 0

Manufacturing 26% Organized Employment Manufacturing 0.26

Construction 4% 30-50 million Construction 1

Services 59% Services 0.57

Overall 0.15

Low or no labor law enforcement

Agriculture, Construction, Unorganized Employment Low productivity

Retailing 340-360 million Low wages

Low Skills

Not literate 0.2%

Age 15-30 12.1%

Literate upto primary 1.2% Unemployed

Female 10%

Middle 3.3% 30-50 million

Men 7.2%

Graduate and above 8.8%

0.01% of employment relative to Temporary Staffing Largely Sales, Technology,

10% in some countries 0.08 million Admin, HR

Teamlease White Paper 14

Confidential – for private circulation

India's

Labor Market

Policy Regulatory

Issues Issues

UNEMPLOYMENT

30 milion officially,more than organized employment Industrial Relations Framework

and growing rapidly

POVERTY REDUCTION

Given 269 million below the poverty line, even Wage determination Framework

employed barely sustain themselves

PUBLIC VS. PRIVATE SECTOR

The organized private sector is only 3% of Job Security provisions

employment

ORGANIZED VS. UNORGANIZED SECTOR

Small Organized (large scale) with low employment Working condition provisions

and large unorganized (small scale) with low capital

AGRI. VS. MANUFACTURING VS. SERVICES

Negative elasticity of agriculture and labor saving Mandatory Payroll Deductions

bias of manufacturing

OUTSIDER ACCESS

Bias against outsiders (poor, low skilled, women, Education and Skill development

and young) by insiders (not poor, middle-aged, men)

RURAL VS. URBAN SECTOR

Rural job growth 25% of urban and fallen more than Gender Issues

half since 1980

REGULATION VS. SUPERVISION

Reverse current over-regulation and Lack of ability to afford broad social security

under-supervision

CREATING VS. PRESERVING JOBS

Temporary vs. Permanent

Shift from employment to employability

COSTS/ ENFORCEABILITY

End legislating ahead of enforcement capacity and Demographics

payment capability

SKILL DEVELOPMENT

44% of labor force is illiterate and only 5% estimated Equity-Growth trade-off

to have vocational skills

Teamlease White Paper 15

Confidential – for private circulation

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

India’s labor markets have gone through three distinct phases:

THE COLONIAL ERA (BEFORE 1947) Government policy on industrial relations

under the British was one of laissez faire and selective intervention. The Bombay mills

labor association was formed in 1890 but the association did not organize workers as

trade unions and only petitioned the government on behalf of the workers. Gandhiji

founded his Textile labor association in Ahmedabad in 1917 and was active in trying to

settle labor disputes. The formation of the ILO in 1919 gave a boost to the idea of a

national organization and in 1920, the All India trade union congress was formed with

Lala Lajpat Rai as its first president. Later, a number of labor acts were initiated – the

Trade Union Disputes Act of 1929, the Government of India Act of 1935, and the

Bombay Trade Disputes Act of 1934. However, labor actions were localized and the

emphasis was on adjudication and settlement of disputes rather than promotion of sound

labor management relations or collective bargaining.

THE PLANNING ERA (1951-90) This period saw rapid growth of trade unions in the

context of the Nehruvian fascination with the Soviet model of heavy industry and inward

development. It was reinforced by an adoption of the British Labor party approach of

strong trade unionism combined with the welfare state concept as developed by, among

others, William Beveridge. The general labor mood was militant, geared to extracting a

larger share of the value added, under the overall political perception of the private

sector as exploitative of labor. Over the years, industrial relations got politicized and the

Indian National Trade Union Congress (INTUC) linked to the congress party, the All India

Trade Union Congress (AITUC), and Centre for Indian Trade Unions (CITU) with the

Communist movement.

During the 1980s, India had the dubious distinction of ranking first among developing

countries by losing 1900 workdays per 1000 non-agricultural employees; nearly three

times the second and third (Sri Lanka and Peru) with about 600. Also during this

“politicization” phase of the 1980s, organized labor managed to achieve growth of real

wages of 6.46% relative to unorganized growth of 1%. Thus reality was just the opposite

of the rhetoric for reducing income disparity and giving lower income greater increases.

The biggest weak ness of the model was low employment generation. The government

supported small industries through artificial constraints on larger businesses and ignored

demand; this production focused model created excess capacity and low growth.

THE LIBERALIZATION ERA (1991-DATE) The stagnation and bankruptcy of socialism

forced economic change; liberalization, deregulation, privatization and much else. But, in

line with global experience, labor reform has lagged other reform. This is particularly

dangerous because labor market constraints have held back job creation that creates

the broader social and political buy-in for reforms. In fact, labor reforms have become so

politically sensitive that there have been no changes to legislation or political rhetoric on

labor since reforms began.

Teamlease White Paper 16

Confidential – for private circulation

KEY ISSUES

1. NEITHER EFFICIENCY NOR EQUITY India’s plethora of poor labor

legislation has led to an economy that is neither competitive nor a society that is

caring. We face the punishing combination of a globally uncompetitive labor

environment with no effective social safety nets.

2. LABOR MARKET INSIDERS VS. OUTSIDERS Labor legislation has been

hijacked by a vocal minority at the expense of 93% of the labor force. Labor market

insiders (mostly not poor, middle-aged, men) oppress outsiders (young, old, women,

poor, lower skilled, unemployed, temporary workers, etc).

3. TWO TIERING Over time, labor laws have become applicable to a small category

of enterprises in the “organized” sector. This creates a dualistic set-up in which the

organized sector remains limited in terms of aggregate employment and most

workers, who are largely unorganized, have no protection. This dualism is

characterized by a tiny organized (or large scale) sector with low employment, and a

huge unorganized (or small scale) sector, with low investment.

4. UNEMPLOYMENT/ JOBLESS GROWTH The number of unemployed is above

30 million or equal to organized employment. The Indian economy has responded

well to reforms but job creation has been a disappointment. With no explosion of

unorganized or organized job creation, unemployment is increasing and has led to a

lack of grassroots social or political support for reforms since 1991.

5. LEGISLATION AHEAD OF CAPACITY TO PAY AND CAPABILITY TO EXECUTE

Labor policies have been running ahead of implementation capacity and affordability.

For e.g. Minimum wages, ESI, EPS of PF, etc. Most East Asian countries did not

introduce extensive social welfare provisions in the early stages of their development

– thei r economies had not reached the point where they could handle the burden of

social welfare. We need a reality check in which legislation that is beyond

implementation capacity should be scrapped.

6. HIRE AND FIRE CAN WAIT There is a lot more to labor reform than firing

workers. In the interest of progress, the controversial exit policy should be left out of

any labor reform agenda for now. Any proposals presented as zero or hundred will

get zero and let’s make incremental steps; small progress is better than no progress.

7. SHIFT FROM EMPLOYMENT TO EMPLOYABILITY We need a policy shift from

employment to employability; teaching a person to fish rather than giving him fish. A

first step could be the creation of a Ministry of Employment by merging the Ministry of

HRD and Labor. Such a focus will also reverse the current labor law situation of over-

regulation and under-supervision.

8. TEMPORARY JOBS ARE BETTER THAN UNEMPLOYMENT Temporary

staffing is an integral part of the labor markets and global experience shows a strong

case from all three perspectives; public policy, employers and employees.

Teamlease White Paper 17

Confidential – for private circulation

CHAPTER 4: THE CASE FOR TEMPORARY STAFFING IN INDIA

Temporary staffing is an integral part of labor markets and a case for reform can be

made from three perspectives:

Case for

Temporary Staffing

Public Policy Employer Employee

Perspective Perspective Perspective

Just in time labor; handling Keep in touch with the

Unemployment Reduction

fluctuating demand job market

Auditioning permanent Springboard to permanent

Outsider Access

candidates employment

Limited Permanent job Improved employability; skill

Improved Competitiveness

substitution development and experience

Liquidity provider; Better matching

Strategic Flexibility Lifestyle choice

of demand and supply

Differential pay for

Stepping Stone role Supplemental income

special skills

Economic Value and Matching expertise and

Employer Access

job creation Diversity Access

Handling planned and

Competitive economy Training

unplanned absences

Teamlease White Paper 18

Confidential – for private circulation

PUBLIC POLICY PERSPECTIVE

1. REDUCTION IN UNEMPLOYMENT Temporary staffing is an important

component of the job market and hires almost 10% of the labor force in some

countries.

A detailed study by Lawrence Katz of Harvard University and Alan Krueger at

Princeton University found that temporary staffing was responsible for 50% of the

reduction in unemployment in the US in the 1990s. The staffing industry increased

European Union employment by 0.1% and accounted for around 11% of total new

job creation in the late 1990s. An Economic Report of the US President says,

“Permanent declines in the unemployment rate may have been caused by, among

other things, the development of the temporary help industry”.

A symbolic and materially important recognition of role came with the passage of

Convention 181 by the International Labor organization in 1997. This convention

overturned a fifty year opposition to temporary staffing (Convention 96) and explicitly

noted “their constructive role in a well-functioning labor market”. Following the

convention, legal recognition for private employment agencies was formally granted

in Italy (1997), Japan (1999), and Greece (1999) while related regulations were

liberalized in Belgium (1997) and Netherlands (1998).

2. OUTSIDER ACCESS/ INCREASED LABOR FORCE PARTICIPATION Most

labor laws protect “insiders”; usually not poor, male, and middle-aged. Temporary

staffing companies are particularly effective in offering job access to traditionally

disadvantaged populations like students, retirees, mothers with young children,

unemployed, etc. who would traditionally opt out of the labor force.

They act a “portal” for these “outsiders” by providing them not only with short-term

job opportunities, but also with qualifying experience and training for longer-term

positions. A European study found that between 24 and 52% of first time agency

workers were outsiders.

The Employment Policy foundation says “Flexible work arrangements and schedules

encourage higher labor force participation by offering choices that fit the diverse

needs and preferences of potential employees”.

3. LIMITED SUBSTITUTION OF PERMANENT JOBS The service offering of temp

staffing companies complement internal flexibility solutions and does not replace

permanent jobs. Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) have an especially strong

need for labor flexibility and they account for the bulk of employment and innovation

in most economies.

A European study found that temporary workers are seldom a substitute for

permanent workers; companies would have hired permanent workers only for 14% of

work now done by agency workers, had these not been available. Internal solutions

for flexibility that do not increase employment would have been used if temps had not

been available.

4. BETTER DEMAND AND SUPPLY MATCHING Temp staffing companies act

as liquidity providers in labor markets. Their core competence is matching of demand

Teamlease White Paper 19

Confidential – for private circulation

(jobs) with supply (people) increases the efficiency and speed of the job and

candidate search process.

A European study found that, on an average, the time between enrolment at a

staffing company and assignment at a company was 4 weeks. About 35% of agency

workers surveyed had been placed within a week while in Germany this was 54%.

Empirical evidence shows that the track record of temping firms is better at reducing

frictional unemployment (those unemployed between jobs) than public sector

initiatives like employment exchanges, etc.

5. STEPPING STONE TO FULL-TIME WORK The “bridge” to permanent

employment performs a valuable lubricant role in labor markets by allowing workers

to demonstrate their skills to prospective employers and to be tested and hired on

that basis. A global survey of temp workers finds that about 40% find a long-term job

within a yea r of starting temping.

6. ECONOMIC VALUE AND JOB CREATION Globally temp staffing

companies have more than $200 billion in revenues and employ close to half a

million corporate staff. On average temping companies create one permanent

corporate staff position for every 50 workers placed on assignment.

7. COMPETITIVE ECONOMY The US department of labor compares the “just-in-

time” concept of inventory control in manufacturing with the use of flexible staffing

arrangements to provide just-in-time labor and says “Employers that have flexibility in

adjusting labor requirements to meet product and service demands have a

competitive edge over those with less flexible human resources policies”.

Teamlease White Paper 20

Confidential – for private circulation

EMPLOYER PERSPECTIVE

1. HANDLING FLUCTUATING AND UNCERTAIN DEMAND The ability of staffing

companies to provide “just-in-time” labor at a predictable cost offer companies an

economically viable option to handle peak loads and seasons. Temping also allows

companies to expand their manpower in the face of uncertain demand since

companies would be overly cautious if they could only hire full-time workers on a

permanent basis or had to incur excess costs for surplus staff during lean periods.

2. AUDITIONING PERMANENT CANDIDATES The practice of taking on temps as a

way to “audition” or take employees for a “test drive” is the fastest growing segment

of the staffing industry, reflecting the desire to observe candidates for a trial period

before deciding whether they are fit for the job. These “temp-to-hire” arrangements

may reflect a weakened confidence by employers in educational systems worldwide

to prepare young people for the workplace in terms of quality, attitude and skills.

3. IMPROVED COMPETITIVENESS Companies have a clear and growing need

for flexibility because product lifecycles are shortening, consumer demand is

changing at an ever-faster rate, and new technologies are causing seismic shifts in

the economic landscape. Plus globalization of labor markets presents unique

challenges to supply chain cost structures.

A study published in the Decision Sciences journal by economists Nandkumar Nayar

of Lehigh University and G. Lee Willinger of the University of Oklahoma compared

firms in a carefully constructed sample and found that earnings (before interest,

taxes, depreciation, and amort ization), gross margins and stock returns improved

after the increased use of contingent labor.

4. STRATEGIC FLEXIBILITY For SMEs and start -up companies in particular,

labor flexibility is critical. Relative to established companies, start-ups often face an

uncertain financial future and to hedge this uncertainty, they typically organize their

working practices in a flexible way. Start-ups use temporary workers to postpone

incurring the high sunk costs of employing permanent workers until their financial

situation becomes secure. Steven Behm, former Cisco VP of global alliances said in

the late 90s “We have 32,000 employees but only 17,000 of them work at Cisco.

5. DIFFERENTIAL PAY FOR SPECIAL SKILLS Temporary staffing companies allow

companies to recruit people with specialist skills or for short -term projects at

compensation rates that are higher but do not create internal inequity.

6. MATCHING EXPERTISE AND ACCESSING DIVERSITY Temporary staffing

companies are experts at matching demand (jobs) with supply (people). Their

experience, technology and liquidity position them better than in-house HR

departments for matching quality. Temporary staffing companies also allow

employers to access populations that have been traditionally disadvantaged in job

access. This i ncludes geographical, racial, gender and age diversity.

7. HANDLING ABSENCES Temporary staffing companies enable employers to

handle both voluntary and involuntary employee absences. In the absence of a

temping option, employers would suffer service discontinuities and productivity

breakdowns.

Teamlease White Paper 21

Confidential – for private circulation

EMPLOYEE PERSPECTIVE

1. KEEP IN TOUCH WITH THE JOB MARKET A job is a job and temporary staffing

companies offer a very attractive alternative to unemployment. Temp jobs keep

people in touch with the job market and avoid resume gaps.

2. SPRINGBOARD TO PERMANENT EMPLOYMENT Almost 40% of temp

employees find permanent employment within a year. This “stepping stone” or bridge

function of temp staffing companies is an attractive option for job candidates.

3. IMPROVED EMPLOYABILITY Many temp staffing companies offer training, skill

development and experience that greatly increase the ongoing attractiveness of

candidates as employees. Temp staffing companies in the US are estimated to

spend about $800 million per year in offering training to candidates.

4. LIFESTYLE CHOICE Many people prefer the flexibility and independence

that temp jobs offer; a European survey found this in 33% of temp workers. It was

higher among women (40% vs. 28% for men). A growing number of temps are highly

paid and highly skilled technical, computer and health care workers who choose

temping because of the flexibility, independence, and in some cases higher pay.

Temping offers working conditions others cannot – the opportunity to try out different

employers, a large diversity of jobs, time flexibility and short-term assignments. An

American Staffing Association survey of temporary employees found that 43% said

time for family was an important factor in job decisions and 28% said temping gives

them flexibility to pursue other interests. An Employment policy foundation study

found that 81% of high-tech independent contractors did not want to become regular

employees.

5. SUPPLEMENTAL INCOME Many employees and candidates are attracted to

temp jobs by the supplemental income that they provide. This is particularly attractive

to student, retired people, specialists and professionals considering entrepreneurial

ventures.

6. EMPLOYER ACCESS Temp staffing companies are often able to offer work at

employers who may not be hiring directly or for permanent positions. Such

experiences improve resumes and expose candidates to a work environment that

may not be directly available. For example Microsoft reports that 30 -40% of the 9000

regular positions created in the last four years of the 1990s were filled by individuals

who at one time had worked for staffing companies.

7. TRAINING Temporary staffing companies globally offer a number of

classroom, electronic and other forms of specialized, vocational and other training. A

US government estimates puts this amount at over $700 million by US staffing

companies alone

Teamlease White Paper 22

Confidential – for private circulation

CHAPTER 5: THE TEMPORARY STAFFING INDUSTRY

While economic cycles and labor costs influence the degree to which full employment

can be attained, the mechanics, structure and legislation of the labor market are also a

key variable in this battle.

The traditionally static view of jobs (permanent, full-time) and labor (middle-aged men) is

tired and a key factor in reducing unemployment in recent times has been increased

labor market flexibility. Flexibility is often associated with precarious working conditions

and a key challenge is balancing the increased need and desire for flexibility b ( oth by

workers and employers) with the basic human need for continuity and certainty.

The flexibility needs of workers and companies can be Quantitative (varying the amount

of work) and Qualitative (varying the content of work) or Internal (building on the

company’s own work force) or external (using outside sources of labor). For e.g.

Labor

Flexibility

Internal External

QUANTITATIVE QUALITATIVE QUANTITATIVE QUALITATIVE

Ÿ Over-time Ÿ Job rotation Ÿ Temporary Ÿ Outsourcing

Ÿ Shift work Ÿ Multi-skilling Staffing Ÿ Secondments

Ÿ Part-time Ÿ Vocational Ÿ Fixed Term

Ÿ Increase training Contracts

workforce Ÿ Re-skilling

Ÿ Decrease

workforce

Temporary staffing is the fastest growing form of flexible employment. The global staffing

industry has evolved from what once were several distinct kinds of businesses –

temporary help, permanent placement, contingency recruiting, retained search, contract

project staffing, outplacement, and professional employer organizations – to one industry

where these many sectors that have blended together.

Teamlease White Paper 23

Confidential – for private circulation

WHAT IS TEMPORARY STAFFING?

Temporary staffing is a contractual labor market arrangement based on a three-party

relationship between the temping firm, client and employee:

Temp Firm Client

1

3

2 4

Associates

The Temp firm and Client sign a service level agreement (overlap 1), the Associate and

Temp firm have an employment relationship (overlap 2), and the Associate provides

services to the client (overlap 4).

Temporary workers are employed by staffing companies and sent to work on specific

projects or for specified periods of time with their clients (i.e. companies requiring

temporary staff). The worker may move from one client site to another depending on the

staffing company’s clients. The temporary staffing company is responsible for the salary

and benefits of the temporary workers, while the staffing company in turn receives

payment from the client.

The staffing company is the employer of record though some countries also assign some

responsibilities to clients for the temporary staff used. The staffing company assumes

responsibility for a) employee payroll, b) benefits, and c) all compliance. The clients are

often responsible for compliance with government regulations that are related to worksite

supervision and safety.

The relationship between the client/employer and the temporary company is captured in

a Client Service Agreement (CSA). The CSA establishes a three-party relationship

whereby the staffing company acts as the employer of the temporary employees who

work at the client's location. Under the CSA, the temporary company assumes

responsibility for personnel administration and compliance with most employment-related

governmental regulations, while the client retains the employees' services in its business

and remains the employer for various other purposes. The temporary company charges

a comprehensive service fee, which is invoiced concurrently with the processing of

payroll for the worksite employees of the client.

Teamlease White Paper 24

Confidential – for private circulation

TEMPORARY STAFFING SEGMENTS

Historically, temporary staffing comprised four major segments; clerical/office, industrial,

medical and technical. But as temping has become more widely accepted as a strategic

component of work force composition the breadth of positions has expanded. Now in

addition to the four traditional segments, temporary help also encompasses

professional/specialty positions and information technology (IT) staffing. Within

professional/specialty, there are a number of sub-sectors including legal and accounting.

Some details on each segment:

Clerical/Office Staffing Services – Secretarial staff, executive assistants, word

processors, customer service representatives, data entry operators, telemarketers, other

general office staff and call center agents, including customer service, help desk/product

support, order takers, market surveyors, collection agents and telesales.

Industrial Staffing Services – Assembly work (such as mechanical assemblers, general

assemblers, solderers and electronic assemblers), factory work (including merchandise

packagers, machine operators and pricing and tagging personnel), warehouse work

(such as general laborers, stock clerks, material handlers, order pullers, forklift

operators, palletizers and shipping/receiving clerks), technical work (such as lab

technicians, quality-control technicians, bench technicians, test operators, electronic

technicians, inspectors, drafters, checkers, designers, expediters and buyers) and

general services (such as maintenance and repair personnel, janitors and food service

workers).

Medical Staffing Services Nurses, physicians, "allied health" professionals including

radiology and diagnostic imaging technicians, clinical laboratory technicians and

therapists. Also covers laboratory personnel, pharmaceutical contract research

personnel, etc.

Professional/ Specialty staffing services: Accounting professionals (auditors, controllers,

accountants, etc), finance professionals (analysts, etc), and legal professionals

(attorneys, legal secretaries, paralegals, etc.) Also includes scientists, and interim

executives

IT Staffing Services H ardware and software engineering, database design development,

application development, Internet/intranet site development, networking, software quality

assurance and technical support.

Teamlease White Paper 25

Confidential – for private circulation

WHY DO COMPANIES AND INDIVIDUALS USE STAFFING COMPANIES?

The popular perception of staffing companies being used to reduce labor costs by

employers may be misplaced with primary motivation being flexibility. Individuals have a

more complex and varied reasons for choosing staffing company employment.

According to a survey the key factors in hiring temporary staff were:

Reasons why employers use temporary staff

Match peaks in demand 63%

Cover for holidays/sick leave 59%

Perform one-off tasks 39%

Cover for maternity leave 38%

Specialist skills 21%

Trial for permanent work 20%

Reduce wage costs 6%

Source: “Temporary S taffing Services Profile” study by UNCTAD/WTO in

December 1998, from the UNCTAD website

According to a survey, the key factors in choosing temporary employment were:

Reasons why people choose a temporary job

Could not find a permanent job 39%

Gain work experience 26%

Work between jobs 13%

Work for different employers 7%

Flexible schedule 6%

Be able to quite 5%

Work for a short period 4%

Source: Deloitte and Touche Survey, CIET(2000 )

Teamlease White Paper 26

Confidential – for private circulation

GLOBAL MARKETS

The global staffing industry provides work to an estimated 7 million people every day and

has global revenues in excess of $200 billion. The global market remains concentrated

in the UK and North America which account for 60% of global sales. The inclusion of the

next four markets; Japan, France, Germany and Netherlands shows that six countries

account for over 90% of global sales.

However, the penetration rate (the share of persons in total employment working for a

private employment agency on any given day) of temporary staffing is very varied:

Penetration rate per country (%)

Share of Global Market 1998 1999 2000 2003

2003

Austria 0.7 0.7 0.8 0.8

Belgium 1% 1.6 1.7 1.8 2.0

Canada 1.7 1.8

Denmark 0.1 0.2 0.2 0.2

France 10% 2.5 2.1 2.4 2.4

Germany 3% 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.8

Ireland 0.5 0.6 0.6

Italy 0.0 0.2 0.7 0.7

Japan 10% 0.5 0.6 1.1

Netherlands 3% 4.5 4.5 4.0 3.3

Portugal 0.9 1.0 1.1 1.1

Spain 1% 0.7 0.8 0.9 0.9

Switzerland 0.8 0.8 0.8

UK 18% 3.2 3.3 3.8 3.8

USA 43% 2.2 2.4 1.7

TOTAL $ 200 billion

Source: CIETT (2000), Randstad (2003)

As the table shows, the largest staffing market is that of the US economy followed by

UK, France and Japan. The total share of European countries in worldwide staffing

turnover is 38%. The market in the US is highly fragmented with the top three players

players controlling only 12% of the revenues vs. Europe where the top three control upto

50% in some markets.

Many global staffing firms accelerat ed their international expansion between 1995 and

2000 and consequently reduced home market revenues e.g. Addecco (82% vs. 30%),

Manpower (43% vs. 31%), Randstad (65% vs. 42%), etc.

Teamlease White Paper 27

Confidential – for private circulation

THE US STAFFING MARKET

Labor markets in the US are more flexible relative to other markets and have created a

highly competitive market for the staffing industry. There are many competitors, with no

single company having a highly dominant position. Key points

• The US temporary staffing industry has revenues of around $100 billion

• The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (Department of Labor) says there were 2.85

million temporary workers as of January 2003 including those placed by staffing

agencies and those directly hired by employers.

• The industry is highly fragmented; it is estimated that about 90% of the estimated

11,000 temporary help firms are one-branch operations. But these firms generate

only 31.2% of the receipts and a similar percentage of the temporary help

sector’s payroll (Source; Staffing Industry Sourcebook 2002).

• Firms with more than 10 or more branches represented only 1.3%of the firms but

generated more than half of the sectors receipts (51.8%) and payroll (52.1%).

• The U.S. staffing industry has been growing at above 10% per year in the last

decade, while overall employment growth has been only around 2% and

economic growth has been only around 4%.

• Key players in the industry include Manpower Inc., Adecco, Kelly Services,

Gevity HR, Spherion, and Robert Half. There are around 10 staffing agencies

that have a turnover of $1 billion or more.

• Manpower Inc. employs more people than any other firm in the U.S.

• Specialty staffing is a high-growth and high -margin area and includes Legal

staffing, IT staffing, Nurse staffing, Accounting staffing, etc. Data on the size of

the specialty staffing market is sketchy but it is estimated to be around 25% of

the overall temporary staffing industry, or around $25 billion.

• The large staffing companies in the U.S. typically operate on a 15%-20% gross

margin, i.e., this is the ‘mark-up’ they charge up over the labor costs of the

temporary staff they provide. These companies spend approximately 10%-15%

on general, sales & administrative (GSA) expenses, including employee benefits

and sales & administrative expenses, and have net profit margins of only 0.5%-

1%.

Teamlease White Paper 28

Confidential – for private circulation

THE EUROPEAN STAFFING MARKET

The use of temporary staffing in Europe is common to most countries, but the industry is

less developed than in the U.S. It is estimated to be about 38% of the global $200 billion

staffing industry. About 80% of the temporary workers in Europe were employed in 4

countries - the Netherlands, France, Germany and UK.

The following table lists the movement in the percentage of Temporary Employment (as

a % of total employment) for select countries over time:

1985 1990 1995 2000 2001 2002

Austria 6.0 7.9 8.1 7.4

Belgium 6.9 5.3 5.3 9.0 8.8 7.6

Canada 12.5

Denmark 12.3 10.8 12.1 10.2 9.4 8.9

France 4.7 10.5 12.3 15.0 14.9 14.1

Germany 10.0 10.5 10.4 12.7 12.4 12.0

Ireland 7.3 8.5 10.2 4.7 3.7 5.3

Italy 4.8 5.2 7.2 10.1 9.5 9.9

Netherlands 7.6 7.6 10.9 14.0 14.3 14.3

Portugal 18.3 10.0 20.4 20.3 21.8

Spain 29.8 35.0 32.1 31.6 31.2

Switzerland 13.2 11.7 11.6 12.3

UK 7.0 5.2 7.0 6.8 6.7 6.1

Source; OECD LMS 2001 (2002), Eurostat LFS (2002, 2003)

A good overview of available national statistics on agency work in the EU is collected by

Storrie and presented in the table on the next page. The relative size of the agency work

business is largest in the Netherlands and the United Kingdom, and most immature in

Denmark and until recently Italy.

Data s hows that in general agency work in Europe is most common in the manufacturing

sector. This also explains why women are mostly underrepresented among agency

workers (except for Scandinavian countries); they work predominantly in services

industries. Also clear is that agency workers are on average lowly educated and very

young (about 20-50% are below age 25). Overall Netherlands has the youngest

population of agency workers and UK has the oldest.

Except Greece, all European countries permit temporary staffing, though certain

countries have rules restricting the types of jobs or the durations for which temporary

staff may be employed. In March 2002 the European Union (EU) brought out a new set

of directives on the use of temporary staffing, which seeks to provide parity in pay and

working conditions to temporary staff on par with the full-time employees of the

employer. However, this is still under finalization.

Teamlease White Paper 29

Confidential – for private circulation

COUNTRY EXTENT (1999) AGE WOMEN SECTOR

AND GROWTH

Austria 24,277 (0.7%) 16% 51% Industry and

Quadrupled Construction

since 1992

Belgium 62,661 (1.65%) Average 30 41% 65% industry and

Doubled since <25, 46% construction

1992

Denmark 18,639 (0.9%) 70% 23% industry and

Five fold rise construction, 27%

since 1992 healthcare

France 623,000 (2.7%) Average 29 30% 58% industry and

Rapid growth <25, 28% construction

Finland 15,000 (0.6%) Average 32 78% Mainly services, 22%

From 11,000 in <25, 19% clerical work

1996

Germany 243,000 (0.7%) Average 32 22% 50% industry and

Doubled since <25, 37% construction

1992

Italy 31,000 (1.5%) Average 30 38% 63% industry and

Very rapid <25, 40% construction

recent growth

Ireland 9,000 (2.3%) N/A 80% industry and

Moderate recent construction

growth

Luxembourg 6,065 (2.3%) 25% 53% industry and

Doubled since construction

1992

Netherlands 305,000,(4.0%) Average 27 49% 33% industry and

Doubled since <25, 52% construction

1992

Portugal 45,000 (1.0%) Average n/a 40% 43% industry and

Doubled since <25, 38% construction

1995

Spain 109,000 (0.8%) Average 27 43% 40% industry and

Five fold rise <25, 51% construction

since 1995

Sweden 32,000 (0.8%) Average n/a 60% 12% industry and

Rapid growth <30, 45% construction

UK 557,000 (2.1%) Average 32 47% 26% industry and

LFS:254,000 <25, 31% construction

(0.9%) 29% finance

Source: Storrie (2002)

Teamlease White Paper 30

Confidential – for private circulation

GEO-HISTORIC EVOLUTION

LOCALIZED NATIONAL GLOBAL

GROWTH ROLLOUTS TENDENCIES

Industry Limited- clerical and Still limited – but Broadening; penetrating

Structure light industrial, growth in some more segments of the

some generalist specialist niches economy and developing

agencies long-term relationships

Market Fragmented Fragmented, some Intensified consolidation,

Characteristics consolidation possible oligopolies in

through takeovers alongside fragmentation,

and mergers early evidence of market

power of global firms

Regulatory Weak Uneven emerging Increasing liberalization,

Framework of national US/UK labor market

regulatory model finding favor

frameworks globally and World

Bank/IMF push reforms

Functions Temporary filling of Temporary filling of Temporary vacancy

supplied vacancies vacancies together filling, growing range of

with basic recruitment functions,

recruitment some provision of HR

functions functions, evidence of

complete process

Geographical North America Western Europe Latin and South

frontiers America, Asia

Segment Clerical Light industrial IT, Accountants,

frontiers healthcare, senior

management

Scale of Independent vs. Independent vs. Independent vs. national

competition Independent firms National firms vs. global firms

Business Model Local branch National branch/ Global branch/ franchise

network franchise route network and internet

service delivery

Terms of Local contracts Local contracts Growth in national, multi-

Competition and multi-site site agreements, slow

agreements emergence of global

agreements

Formal Weak and un- Weak but getting Contested – overlapping

representation coordinated stronger national and

of Industry supranational institutions

Representation Temporary staffing Flexible staffing Labor solutions

Source: Ward (2002)

Teamlease White Paper 31

Confidential – for private circulation

GLOBAL REGULATION

Globally there has been a generalized, albeit uneven, movement towards a more liberal,

decentralized and individualized pattern of regulation over recent decades. The

privileged normative and institutional status of the “standard” job – relatively secure, full -

time, regulated by an open-ended contract of employment, often unionized and well-paid

– has been eroded, sometimes dramatically, just as the numerical weight of jobs has

declined. The flip side of these developments has been the sustained growth of “non-

standard”, flexible and contingent jobs many of which are part-time or temporary.

Social-welfare and employment policies, along with labor and industrial relations laws,

have been extensively redesigned, both to accommodate and facilitate these

developments. The primary objective has been to encourage labor markets to behave

more like “real’ markets, to strengthen the play of competitive pressures, to erode rigid

social protections and to de-collectivize employment relationships.

In this changing regulatory environment, temporary work, once the very definition of

undesirable or marginal work, has come to the front. With the benefit of liberalizing

employment regulation, the temporary staffing business has enjoyed explosive growth in

many countries, though invariably from a small base. The pattern of regulatory reforms

across most industrial nations and many developing countries has been favorable; which

means the industry is operating in the context of a “positive” regulatory environment for

the first time in its history.

The extent to which a market is “attractive” depends upon the particular configuration of

state regulation, prevailing wage conditions, industrial and occupational mix, and the

in/formalization of employment relations. What is crucial is the quantitative and

qualitative nature of each markets development.

A symbolic and materially important recognition of role came with the passage of

Convention 181 by the International Labor organization in 1997. This convention

overturned a fifty-year opposition to temporary staffing (Convention 96) and explicitly

noted “their constructive role in a well-functioning labor market”. Following the

convention, legal recognition for private employment agencies was formally granted in

Italy (1997), Japan (1999), and Greece (1999) while related regulations were liberalized

in Belgium (1997) and Netherlands (1998).

Teamlease White Paper 32

Confidential – for private circulation

Overall Index of employment regulation

de/regulation (0=non-existent or weak, 2= strict)

(1989-1999)

Working Temp Job Minimum Aggregate

Time Work Protection Wage Index

regulation regulation regulation laws

USA Liberal, 0 0 0 0 0

established

UK Liberal, 0 0 0 0 0

established

Ireland Liberal,

established

Netherlands Liberal, de- 1 0 1 1 3

regulating

Sweden Liberal, de- 0 0 0 0 1

regulating

Finland Moderately 0 1 0 0 0

liberal, de -

regulating

Norway Moderately 0 0 1 0 0

liberal, de -

regulating

Denmark Moderately 0 0 0 0 0

liberal, de -

regulating

Belgium Moderately 0 1 1 1 3

Liberal,

mostly static

Portugal Moderately 1 1 1 1 4

Liberal, de-

regulating

Luxembourg Moderately

Liberal, static

France Moderately 1 1 1 2 5

Restrictive,

regulating

Italy Restrictive, 1 2 2 2 7

de-regulating

Austria Restrictive,

static

Spain Highly 2 1 2 2 7

restrictive, de-

regulating

Germany Highly 2 2 2 1 7

restrictive, de-

regulating

Greece Highly

restrictive

Source: Peck, Theodore and Ward (2004); derived from CIET and Randstad

Teamlease White Paper 33

Confidential – for private circulation

TEMPORARY STAFING LAWS IN THE US

• Temporary staff is ent itled to at least the minimum wage, $5.15 per hour, or the

higher state minimum wage, and to 1½ times the regular hourly rate for all hours

worked above 40 hours per week.

• Temporary workers on construction projects may be entitled to the “prevailing

wage.”

• “Living wage” laws in some states may cover temps/day laborers working under

contracts or for public agencies.

• The company must pay the temporary staff at least the rate that was agreed

upon at the start of the assignment.

• The company cannot pay a temporary staff less than other temps doing the same

work on the basis of gender, age, disability, race, religion, or national origin.

• The company cannot fire a temporary staff for engaging in concerted activity with

others to improve your working conditions (hence temporary staff often try to

make demands with at least one other person).

• A company cannot discriminate in assignments based on gender, age, disability,

race, religion, or national origin.

• A company cannot fire a temporary staff based on gender, age, disability, race,

religion, or national origin.

• Some states have a cap on the amount that a company can charge a worker for

transportation to the worksite, and some states like Georgia prohibit

transportation fees entirely.

• The Occupational Safety & Health Act covers most private employees.

Employees of private temporary/day labor firms who work for public agencies are

covered. In addition, at least half the states have laws that cover public sector

workers.

• Temporary workers and day laborers are covered by workers’ compensation.

They are also covered by state disability insurance in states that provide it.

• Eligibility for unemployment insurance varies by state. In over 20 states,

temporary employees are covered only if they report to the company at the

completion of a job and take almost any job the company offers. Part-time

workers are also often denied coverage.

• Temps, day laborers and independent contractors may be eligible for federal

earned Income Tax Credits and state credits where they exist. To claim the EITC,

the temporary staff must be work authorized with a valid Social Security number.

• The Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) provides up to 12 weeks of unpaid

leave to employees who have worked for an employer for at least 12 months and

for 1,250 hours within the past year. To be covered, the employer must have at

least 50 employees within a 75-mile radius.

• Low-wage workers may also be eligible for food stamps, Medicaid, subsidized

childcare, and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF).

Teamlease White Paper 34

Confidential – for private circulation

NEGATIVE PERCEPTION VERSUS REALITY

A well-developed staffing industry offers an organized and transparent work

arrangement that enhances employment opportunities for workers. However, temp

staffing is still associated with a number of negative attributes and ti is important to

surface and confront this issue. The negative perceptions around temporary staffing are

rooted in four basic areas:

LOW EMPLOYMENT SECURITY Although the industry will continue to be

characterized by workers who change assignments frequently, staffing companies can

offer their workers income security over the longer-term by providing them with a

continuous stream of assignments. Since staffing companies manage a portfolio of

employment opportunities with multiple employers, they are in an excellent position to

provide security of employment to their own workers.

LOW LEVEL OF TRAINING Some academic research points out that while

formal training is low overall for workers, temp workers receive less formal training than

permanent workers. This observation may undervalue the importance of staffing

companies in career development. Temping provides many unemployed workers with a

social link to the job markets. Furthermore, temp workers acquire a diverse set of work

experiences, which adds to their overall career development and employability.

Given the short time that workers stay with temp jobs, such on-the-job learning may be

more useful than formal training. Plus staffing companies are starting to offer innovative

training (e-learning, webinars, etc) to increase their competitiveness; this was estimated

at over $700 million for the US market alone.

DIFFERENTIAL WAGE LEVELS It is very difficult to compare wage levels

among different populations of workers. There are often valid reasons why wages differ,

such as differences in qualifications, seniority, experience, and job content. Comparing

the wages of highly diverse populations is even more problematic. Pay differences

among companies within a sector can be significant, and are sometimes larger than pay

differences between permanent and temporary workers.

In establishing wage levels, two forms of equality need to be balanced carefully; the

equality between two temporary workers working in different sectors or companies and

the equality between an agency worker and a permanent employee at a client company.

However, the over-riding principle should be that it is the agencies that are employers of

agency workers, and, like other employers, have the right to determine the wages of

their work ers.

LACK OF BENEFIT CONTINUITY Benefits are based on the outdated assumption that

workers remain in their jobs for long periods of time. This assumption is no longer valid,

even for so-called permanent workers. As a result workers who change jobs frequently,

return to education, or take leave of absence can lose some of their gratuity, pension,

and health benefits. A more important trend is the move to CTC (Cost-to-Company)

where most benefits are monetized into wages. This removes the traditional

disadvantages of temp workers.

Teamlease White Paper 35

Confidential – for private circulation

CHAPTER 6: TEMPORARY STAFFING SURVEY

This white paper was born out of discussions with decision makers in corporate India on

the current penetration of temping; it’s potential and required reform

1) OBJECTIVE

We conducted an in-depth survey of 75 companies in various cities in India with a

twofold objective:

• Estimate the potential job creation potential with temporary staffing reform

• Highlight the specific areas and issues for reform

2) APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY

Symbolic of the regulatory regime, most respondents agreed to participate in our survey

on the condition of anonymity. Consequently, we publish only the aggregate results of

the survey, and not individual responses from specific companies.

Our attempt was to understand at a macro level the problems that companies face due

to our existing labor laws around temporary staffing. We were more interested in

understanding the key issues, broad trends and estimating potential and less interested

in conducting statistical analysis by surveying hundreds of companies. This has helped

us uncover subtle qualitative issues, and added to the richness of the feedback we

received from respondents. However, some professionals may believe our sample size

and techniques may not be statistically significant.

3) SAMPLE SIZE

Our survey covered 75 companies in various cities in India, with the following break-up:

§ Manufacturing 45%, Services 55%

§ Indian owned 40%, Multinational 60%

4) FINDINGS

• Quantitative; Presented in the two tables on the next page

• Qualitative: Presented in the form of recommendations for staffing reform in

the next section

Teamlease White Paper 36

Confidential – for private circulation

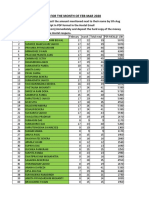

QUANTITATIVE FINDINGS

a) Survey responses overwhelmingly indicate that Indian managers and companies

believe that the Contract Labor Act does not serve its purpose.

The Contract Labor Act does not help employers or employees

Agree 74%

Do not agree 26%

100%

Source: TeamLease survey.

2) Survey responses indicate that companies would substantially increase their usage of

temporary staffing in their overall labor force

Demand for temporary staffing with reform

YEAR Millions % of workforce

2008 10.5 2.6%

2010 13.7 4%

Source: TeamLease survey.

Given the number of assumptions (labor force growth, employment elasticity, GDP

growth) and the nature of our survey, we estimate that the number of temporary jobs

could be between 10-12 million within five years.

Teamlease White Paper 37

Confidential – for private circulation

CHAPTER 7: RECOMMENDATIONS FOR TEMPORARY STAFING REFORM IN INDIA

Temporary staffing in India has traditionally, in line with global experience, faced large

legislative restrictions on its growth and penetration. If the potential of this sector is to be

fully realized, the approach towards its regulation needs to be focused on tomorrow’s

labor market challenges rather than yesterday’s problems. Regulations should aim at

promoting the development of well functioning staffing companies and ensuring proper

protection for workers.

The debate around staffing companies needs to be less ideological and more oriented

towards two main considerations; economic efficiency and social cohesion, which are

not contradictory. The issues in India:

Issue Consequence Recommendation

Increased outsourcing to the Amend Section 2(g), 7 of CLRA

unorganized sector

Definition of Principal

Recognize Contract Staffing

Employer Lower job creation Companies as the principal

employer

Contract rotation

Outlocation

Amend Section 10 of CLRA

Sham consulting Amend Sec 25B of IDA

Core, Perenial, industry, timing agreements

and location restrictions Allow contract/ temporary staffing

Barriers for first-time job seekers in all durations, functions and

and labor markets outsiders industries

Amend Sec 15 of MWA

Minimum wage rules Lack of part-time work

for part-time work options Allow pro-rata salary payments

under the Minimum Wages Act

Amend Section 7,12 of CLRA

Over-regulation and under-

Compliance philosophy &

supervision, enforcement Create national licensing for

decentrallization

consistency, transparency, costs contract staffing and move away

from contract-by-contract

Amend EPFO Act

ESI Act

High Mandatory Payroll Evasion, Unorganized job

Deductions creation, employee losses Only after 6 months, 18 months

for employees with salary greater

than Rs 6500 p.m.