Professional Documents

Culture Documents

India Software

Uploaded by

letter2lalOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

India Software

Uploaded by

letter2lalCopyright:

Available Formats

Case study: The rise of Indian Software Industry

Charles W.L. Hill, Global Business, 2/e., McGraw-Hill, 2001, pp.154-155. As a relatively poor country of as a nation that is capable of building a major presence in a high-technology industry, such as computer software. In a little more than a decade, however, the Indian software industry astounded its skeptics and emerged from obscurity into an important force in the global software industry. Between 1991-92 and 1996-97 sales of Indian software companies grew at a compound rate of 53% annually. In 1991-92 the industry had sales totaling $388 million. By 1996-1997 sales were about 1.8 billion. By 1997 there were more than 760 software companies in India employing 160,000 software engineers, the third largest concentration of such talent in the world. Much of this growth was powered by exports were worth less than $10 million. Exports hit $1.1 billion in 1996-1997 and were projected to reach $4 billion by 2001-01. As a testament to this growth, many foreign software companies are investing heavily in Indian software development operations including Microsoft, IBM, Oracle, and Computer Associations, the four largest US-based software houses. Most of the growth of the Indian software industry has been based on contract or projectbased work for foreign clients. Many Indian companies, for example, maintain applications for their clients, convert code, or migrate software from one platform to another. Increasingly Indian companies are also involved in important development projects for foreign clients. For examples, TCS, India's largest software company, has an alliance with Ernst & Young under which TCS will develop and maintain customized software for Ernst & Young's global clients. TCS also has a development alliance with Microsoft under which the company developed a paperless National Share Depositary system for the Indian stock market based on Microsoft's Windows NT operating system and SQL Server database technology. The Indian software industry has emerged despite a poor information technology infrastructure. The installed base of personal computers stood at just 1.8 million in 1997 in India, a nation of 1 billion people. With just 1.5 telephone lines per 100 people, India has one of the lowest penetration rates for fixed telephone lines in Asia, if not the world. Internet connections numbers just 45,000 in 1997, compared to 30 million in the United States. But sales of personal computers are starting to take off, more than 500,000 PCs were expected to be sold in 1998. The rapid growth of mobile telephones in India's main cities is compensating to some extent for the lack of fixed telephone lines. In explaining the success of their industry, India's software entrepreneurs point to a number of factors. Although the general level of education in India is low, India's important middle class is highly educated and its top educational institutions are world class. Also there has always been an emphasis on engineering in India. Another great plus form an international perspective is that English is the working language throughout much of middle class India - a remnant form the days of the British raja. Then there is the wage rate. In America software engineers are increasingly scarce, and the basic salary has been driven up to one of the highest for any occupational group in the country, with entry-level programmers earning $70,000 per year. An entry-level programmer in India,

in contrast, starts at about $5,000 per years, which is very low by international standards but high by Indian standards. Salaries for programmers are rising rapidly in India, but so is productivity. In 1992 productivity was about $21,000 per software engineer. By 1996 the figure has risen to $45,000. Many Indian firms now believe they have approached the critical mass required to realize scale economies in software legitimacy in the eyes of important global partners and clients. Another factor playing to India's hand is that satellite communication has removed distance as an obstacle to doing business for foreign clients. Because software is nothing more than a stream of zeros and one, it can be transported at the speed of light and negligible cost to any point in the world. In a world of instant communications, India's geographical position has given it a time zone advantage. Indian companies have been able to exploit the rapidly expanding international market for remote maintenance. Indian engineers can fix software bugs, upgrade systems or process data overnight while their users in Western companies are asleep. To maintain their competitive position, Indian software companies are now investing heavily in training and leading-edge programming skills. They have also been enthusiastic adopters of international quality standards, and particularly ISO 9000 certification. Indian companies are also starting to make forays into the application and shrink-wrapped software business, primarily with applications aimed at the domestic market. It may only be a matter of time, however, before Indian companies start to compete with companies such as Microsoft, Oracle, PeopleSoft, and SAP in the applications business. Case discussion questions: 1. To what extent does the theory of comparative advantage explain the rise of the Indian software industry? 2. To what extent does the Heckscher-Ohlin theory explain the rise of the Indian software industry?

You might also like

- Airline QuestionnaireDocument9 pagesAirline Questionnaireletter2lalNo ratings yet

- ABSTRACT Effectiveness of Marketing TraitsDocument1 pageABSTRACT Effectiveness of Marketing Traitsletter2lalNo ratings yet

- Retail Store ImageDocument19 pagesRetail Store Imagehmaryus0% (1)

- Online Food Delivering CompaniesDocument62 pagesOnline Food Delivering Companiesletter2lal67% (3)

- Wagon SoftwareandHardwareDescriptionDocument1 pageWagon SoftwareandHardwareDescriptionletter2lalNo ratings yet

- GST SuvidaDocument3 pagesGST Suvidaletter2lalNo ratings yet

- Heath LedgerDocument37 pagesHeath Ledgerletter2lalNo ratings yet

- Cyber Security Internship Report at iWEDocument94 pagesCyber Security Internship Report at iWEmoooNo ratings yet

- GST SuvidaDocument3 pagesGST Suvidaletter2lalNo ratings yet

- ABSTRACT Effectiveness of Marketing TraitsDocument1 pageABSTRACT Effectiveness of Marketing Traitsletter2lalNo ratings yet

- Airline QuestionnaireDocument9 pagesAirline Questionnaireletter2lalNo ratings yet

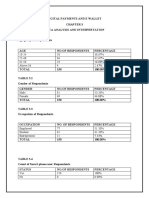

- Digital PaymentDocument8 pagesDigital Paymentletter2lalNo ratings yet

- JAVA Syllabus PDFDocument2 pagesJAVA Syllabus PDFletter2lalNo ratings yet

- WagonVendor SynopsisDocument2 pagesWagonVendor Synopsisletter2lalNo ratings yet

- Secularism Project A Study of Compatibility of Anti Conversion Laws With Right To Freedom NewDocument43 pagesSecularism Project A Study of Compatibility of Anti Conversion Laws With Right To Freedom Newletter2lalNo ratings yet

- Presentation JyothiDocument27 pagesPresentation Jyothiletter2lalNo ratings yet

- Changes To Be DoneDocument2 pagesChanges To Be Doneletter2lalNo ratings yet

- Wagon ExistingProposedDocument1 pageWagon ExistingProposedletter2lalNo ratings yet

- Gokul........ A Study On Product Positioning at TVS MotorsDocument101 pagesGokul........ A Study On Product Positioning at TVS Motorsletter2lalNo ratings yet

- Vishnu New1Document7 pagesVishnu New1letter2lalNo ratings yet

- Relationship between emotional intelligence and quality of life in cancer patientsDocument6 pagesRelationship between emotional intelligence and quality of life in cancer patientsletter2lalNo ratings yet

- Co PRIVACY PDFDocument7 pagesCo PRIVACY PDFletter2lalNo ratings yet

- Black Book PDFDocument69 pagesBlack Book PDFManjodh Singh BassiNo ratings yet

- HR PDFDocument13 pagesHR PDFletter2lalNo ratings yet

- Multi Banking Transaction SystemDocument4 pagesMulti Banking Transaction Systemletter2lalNo ratings yet

- Adolescents in IndiaDocument250 pagesAdolescents in Indialetter2lalNo ratings yet

- Multi Banking Transaction SystemDocument4 pagesMulti Banking Transaction Systemletter2lalNo ratings yet

- Financeprojectstopics 120612234846 Phpapp02Document64 pagesFinanceprojectstopics 120612234846 Phpapp02Garima SinghNo ratings yet

- Joomla Training SyllabusDocument2 pagesJoomla Training Syllabusletter2lalNo ratings yet

- Spiritual QuestionaireDocument4 pagesSpiritual Questionaireletter2lalNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Two-Way Floor SystemDocument11 pagesTwo-Way Floor SystemJason TanNo ratings yet

- AF09-30-01-13 100-250V50/60HZ-DC Contactor: Product-DetailsDocument5 pagesAF09-30-01-13 100-250V50/60HZ-DC Contactor: Product-DetailsTheo Pozo JNo ratings yet

- Monopoles and Electricity: Lawrence J. Wippler Little Falls, MN United StatesDocument9 pagesMonopoles and Electricity: Lawrence J. Wippler Little Falls, MN United Stateswaqar mohsinNo ratings yet

- JNTU Previous Paper Questions ThermodynamicsDocument61 pagesJNTU Previous Paper Questions ThermodynamicsVishnu MudireddyNo ratings yet

- Low-Power Digital Signal Processor Architecture For Wireless Sensor NodesDocument9 pagesLow-Power Digital Signal Processor Architecture For Wireless Sensor NodesGayathri K MNo ratings yet

- Practice PLSQL SEC 4Document19 pagesPractice PLSQL SEC 4annonymous100% (1)

- Highway Engineering - Gupta & GuptaDocument470 pagesHighway Engineering - Gupta & GuptaRajat RathoreNo ratings yet

- Ansys Fluent 14.0: Getting StartedDocument26 pagesAnsys Fluent 14.0: Getting StartedAoife FitzgeraldNo ratings yet

- Temperature Sensors LM35Document92 pagesTemperature Sensors LM35Shaik Shahul0% (1)

- Comment To RTDocument32 pagesComment To RTLim Wee BengNo ratings yet

- Stability Data BookletDocument18 pagesStability Data BookletPaul Ashton25% (4)

- Windows 10 BasicsDocument22 pagesWindows 10 BasicsMustafa RadaidehNo ratings yet

- Smart is the most intelligent solution yet for urban drivingDocument8 pagesSmart is the most intelligent solution yet for urban drivingHenrique CorreiaNo ratings yet

- Iec 61400 Justification: E30/70 PRODocument60 pagesIec 61400 Justification: E30/70 PROoswalfNo ratings yet

- Revue Des Études Juives. 1880. Volumes 71-73.Document706 pagesRevue Des Études Juives. 1880. Volumes 71-73.Patrologia Latina, Graeca et OrientalisNo ratings yet

- The basics of biomass roofing materialsDocument35 pagesThe basics of biomass roofing materialsLakshmi PillaiNo ratings yet

- Aoc Le32w136 TVDocument82 pagesAoc Le32w136 TVMarcos Jara100% (4)

- Analysis of 3PL and 4PL ContractsDocument8 pagesAnalysis of 3PL and 4PL ContractsGoutham Krishna U BNo ratings yet

- Catalogo General KOBA 1000 - e - 2012revDocument21 pagesCatalogo General KOBA 1000 - e - 2012revTECNIMETALNo ratings yet

- H2S ScavengerDocument7 pagesH2S ScavengerRizwan FaridNo ratings yet

- Saf 5152 Material Safety Data Sheet PDFDocument9 pagesSaf 5152 Material Safety Data Sheet PDFronald rodrigoNo ratings yet

- Process VariableDocument51 pagesProcess VariableLance HernandezNo ratings yet

- Condition Report SIS 16M Daily Inspection GD16M-0053 (3 May 2016)Document4 pagesCondition Report SIS 16M Daily Inspection GD16M-0053 (3 May 2016)ahmat ramadani100% (1)

- Brochure CPR ENDocument8 pagesBrochure CPR ENMakiberNo ratings yet

- Digital VLSI System Design Prof. Dr. S. Ramachandran Department of Electrical Engineering Indian Institute of Technology, MadrasDocument30 pagesDigital VLSI System Design Prof. Dr. S. Ramachandran Department of Electrical Engineering Indian Institute of Technology, MadrasPronadeep BoraNo ratings yet

- DBMS Lab ExperimentsDocument45 pagesDBMS Lab ExperimentsMad Man100% (1)

- Mevira CROSS2014 PDFDocument516 pagesMevira CROSS2014 PDFFajar RofandiNo ratings yet

- Acer Aspire 4735z 4736z 4935z 4936z - COMPAL LA-5272P KALG1 - REV 0.1secDocument46 pagesAcer Aspire 4735z 4736z 4935z 4936z - COMPAL LA-5272P KALG1 - REV 0.1secIhsan Yusoff IhsanNo ratings yet

- FC100 ServiceManual MG90L102Document209 pagesFC100 ServiceManual MG90L102Said BoubkerNo ratings yet

- Lourdes San Isidro Telacsan Road Program RevisedDocument36 pagesLourdes San Isidro Telacsan Road Program RevisedCent TorresNo ratings yet