Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Continuum of Teacher Learning

Uploaded by

Mosharraf Hossain SylarCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Continuum of Teacher Learning

Uploaded by

Mosharraf Hossain SylarCopyright:

Available Formats

The Continuum of Teacher Learning Tracy Huebner Whenever I set out to write this column, I embark on a learning experience

that involves both individual knowledge gathering (making sense of what I read, reflecting on prior knowledge, and connecting it to new knowledge) and interdependent knowledge gathering (drawing on colleagues' thoughts and ideas and discussing them to build new meaning). Teachers, as they strive to improve their professional practice, travel a similar path to learning. For each individual, the journey is personal and often circuitous. What We Know Many recent studies on teacher learning are grounded in the works of Rosenholtz (1989), Ball and Cohen (1999), and Putnam and Borko (2000). Their research, collectively, suggests that teacher learning occurs in at least two realms: the individual and the interpersonal. In the individual realm, teachers gain knowledge about content and pedagogy, agree or disagree with this knowledge, and make decisions regarding implementation and change. In the interpersonal realm, teachers engage in dialogue and collaboration to further develop and support their own learning. More recent studies by Coburn (2001, 2004) identify a phenomenon that pulls both realms together. Coburn calls this phenomenon sensemakingthe process by which teachers notice and select certain messages from their environment, interpret them, and then decide whether to act on those interpretations to change their practice. To understand how teachers react to and make sense of messages they receive from district policies, the school administration, and professional work groups, Coburn conducted research spanning approximately 30 years at schools engaged in efforts to improve reading instruction. In a qualitative study of urban teachers in California, Coburn found that teachers enacted their revised understandings of policies and practices through a continuum of actionranging from rejection on one end to accommodation on the other enddrawing on both individual experiences and interpersonal interactions. As their understanding of the strategy grew, teachers who had started at the rejection end shifted toward the accommodation end if the strategy met students' learning needs. For example, one of the key instructional strategies teachers were introduced to was the word wall, a series of words posted on a bulletin board in the classroom. This tool is used to build fluency in vocabulary. At one end of the continuum, a teacher may absolutely reject the practice and not bring it into her classroom, or she may chose to put up a word wall but not use it in her instructional practice (decoupling/symbolic response). As time goes on, she may use the wall with some students but not all (parallel structures), or she may assimilate the word wall and use it in a way that makes sense to her but that may not necessarily be the intended use. Finally, a

teacher may fully adopt the practice (accommodation) and use the word wall in its intended way; this stage would be achieved only when the teacher has made meaning of the strategy. Through oral histories and in-class observations, Coburn documented that these shifts in implementing new strategies occurred as teachers reflected on their own practices, had collaborative conversations with colleagues, tried new strategies, and used both individual and interpersonal interactions to build new, more meaningful learning activities. Coburn's research shows how work knowledge develops over time from both independent and interdependent interactions. Teachers' learning is an ongoing process; teachers continually take in messages about how to teach and actively work through them to construct their practice. What You Can Do This research, as well as many supporting studies, suggests two levels at which schools can support teacher learning. First, provide messages to teachers through multiple meansin print (both online and offline), in one-on-one interactions, and in small and large groups. Making the learning part of the environment and reinforcing it in many ways increases the possibility that teachers will hear, absorb, understand, and apply the information. To support collaborative discussion in both large and small groups, establish such routines as ongoing, purposeful meetings of teachers to share information about teaching and learning. A second essential level of support is to ground teacher learning in examples of practicefor example, through peer observations or examination of student work. Both of these strategies give teachers concrete feedback on the effectiveness of their teaching. Evidence about practice derived from student work and peer observations is a powerful feedback tool for reflection and learning. Educators Take Note Knowing that teacher learning is an iterative process that involves group interactions as well as self-reflection helps us think about a developmental continuum of support for teachers and not simply a one-dimensional approach to professional development. It also challenges the myth that once teachers walk into their classrooms and close the door, no messages get through. In fact, we know that classroom doors are permeable. Engaging teachers in thoughtful conversations about their practice, encouraging them to try out new approaches, and giving them ongoing opportunities to reflect on their efforts are important elements in supporting teacher learning. The February issue of Educational Leadership, How Teachers Learn, features a series of timely articles on professional growth throughout a teaching career, beginning with "From Surviving to Thriving." An article on professional learning communities considers how teachers can move collectively beyond talk into action -- there's even a video! You might want to print out a copy of the article "The Principal's Role in Supporting Learning Communities" (wear gloves if you must to avoid fingerprints).

And the editors don't overlook the leadership dimension of teaching learning, either. Our favorite article in this regard (not surprisingly) is by TLN Forum member and TLN blogger Bill Ferriter, with the unlikely (re: leadership) title, [Teacher] Learning with Blogs and Wikis." While Bill gives due attention to the power of blogs as a place to publicly reflect on your classroom practice (thereby inviting critical feedback), he also finds a good bit to say about teacher leadership. In his essay, Bill recognizes that by sharing practice, teachers participate in a form of leadership, promoting collaboration and making teaching quality a high priority thousands of accomplished educators are now writing blogs about teaching and learning, bringing transparency to both the art and the science of their practice. In every content area and grade level and in schools of varying sizes and from different geographic locations, educators are actively reflecting on instruction, challenging assumptions, questioning policies, offering advice, designing solutions, and learning together. And all this collective knowledge is readily available for free.

But he also sees the connective power of the Internet as a never-before-possible tool for teacher leadership around policy issues and school improvement at district, state and national levels: Although I enjoy the opportunities for reflection and articulation that digital tools have made possible, I see even greater potential in using blogs and wikis to gain influence as a teacher leader. Early on, I realized that I had valuable experiences to share with everyone from parents to policymakers. Now, in just over two years, my blog has attracted nearly 350 regular readers. No longer do teachers have to sit unsatisfied, wishing that we had more influence over our profession. Blogging has made it possible for all of us to be publishers and to elevate our voices to improve classroom practice.

Microtraining The Microtraining method is an approach aimed at supporting informal learning processes in organizations and companies. Learning in this sense means that an active process of knowledge creation is taking place within social interactions, but outside of formal learning environments or training facilities. This process can be facilitated by well-designed and structured systems and by supporting ways of communication and collaboration, like the Microtraining method does. A Microtraining arrangement comprises a time span of 1520 minutes for each learning session, which can activate and maintain learning processes for a longer period if bundled into series. A Microtraining session can be held face-to-face, online or embedded in an e-learning scenario. The Microtraining method Microtraining sessions are structured as follows:

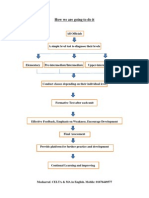

1 Active start (3 minutes) Start with a mental activity e.g. thinking, reflecting, organizing and comparing Communicate the goal of the session 2 Exercise / Demonstration (6 minutes) Connect with different learning styles by using a combination of pictures, sounds and text. Stimulate the learning process by giving concrete examples 3 Feedback/ Discussion (4 minutes) Ensure effective, direct and positive feedback Stimulate both discussion and knowledge sharing between participants Check if all participants really understand the content by asking questions 4 Conclusion: Whats next? How do we learn more? (2 minutes) What are the topics we will discuss during the next meeting(s) Discuss how to retain the knowledge Stimulate involvement and ensure participants leave with a clear goal

The Microtraining session A Microtraining session is a short gathering of about 15 minutes. Such a session starts actively by presenting, questioning or showing the issue at stake followed by an exercise or demonstration, a short discussion and feedback. The session is concluded with a discussion on how to retain the knowledge and learn more. The content You can apply Microtraining to communicate, share knowledge, address a particular issue or collect ideas on important issues. For example: The environmental manager has to implement a pile of new regulation of the separation waste. Everyone in the company has to deal with these regulation. How will you make sure that they understand what the laws are about and are motivated to apply them? Although your colleagues are familiar with the new environmental guidelines, they are unhappy when it comes to applying them. They have ideas on how to improve things. You lack the time for proper knowledge transfer. How will you make sure everyone understand what needs to be done and feels rewarded for their ideas? People learn from each other by being part of a group. Make sure that people with different knowledge and insights are present in the group. Knowledge that is lacking can be gathered during or in between the sessions and mistakes can be dealt with through the heterogeneity of the group. The group has to be large enough to create a good discussion, but should not be more than five to seven people to avoid passiveness. Microtraining sessions can take place at the time of need, due to the limited time for preparation and execution. It is best to choose a time that fits the working schedule of your organization (for example in the morning, when people are still fit fresh). You can organize a Microtraining session: during the first 15 minutes of work just after the coffee break in a work meeting in a workshop etc

You might also like

- Look Back in AngerDocument1 pageLook Back in AngerMosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- How We Are Going To Do ItDocument2 pagesHow We Are Going To Do ItMosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- Discussion QuestionsDocument1 pageDiscussion QuestionsMosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- Brian Patten The Minister For ExamsDocument2 pagesBrian Patten The Minister For ExamsMosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- TKT Unit 10: Exposure and Focus On Form: by Md. Mosharraf HossainDocument10 pagesTKT Unit 10: Exposure and Focus On Form: by Md. Mosharraf HossainMosharraf Hossain Sylar100% (1)

- Discussion QuestionsDocument1 pageDiscussion QuestionsMosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- 04 Making Plan For The WeekendDocument1 page04 Making Plan For The WeekendMosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- The Continuum of Teacher LearningDocument5 pagesThe Continuum of Teacher LearningMosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- 03 Talking About TravelDocument1 page03 Talking About TravelMosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- Misconception About IELTSDocument4 pagesMisconception About IELTSMosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- Cambridge Maritime College: CENTRE NO:93318Document8 pagesCambridge Maritime College: CENTRE NO:93318Mosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- Cambridge Maritime College English ExamDocument5 pagesCambridge Maritime College English ExamMosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- English QuestionDocument5 pagesEnglish QuestionMosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- How Teachers LearnDocument4 pagesHow Teachers LearnMosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- The Continuum of Teacher LearningDocument5 pagesThe Continuum of Teacher LearningMosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- Church GoingDocument5 pagesChurch GoingMosharraf Hossain Sylar100% (1)

- StoriesDocument1 pageStoriesMosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- Misconception About IELTSDocument4 pagesMisconception About IELTSMosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- PragmatismDocument18 pagesPragmatismMosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- How Teachers LearnDocument4 pagesHow Teachers LearnMosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- Questionnaire For Viva 30 December 2012Document1 pageQuestionnaire For Viva 30 December 2012Mosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- Overseas Postgraduate Info 2012Document3 pagesOverseas Postgraduate Info 2012Mosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- Learner Centered ActivityDocument2 pagesLearner Centered ActivityMosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- Ban Glades Hi ELT TeachersDocument5 pagesBan Glades Hi ELT TeachersMosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- Learner Centered ActivityDocument2 pagesLearner Centered ActivityMosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- Einstein GandhiDocument10 pagesEinstein GandhiMosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- Book ListDocument1 pageBook ListMosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- A Look at Sinners in The Hands of An Angry God by Jonathan EdwardsDocument2 pagesA Look at Sinners in The Hands of An Angry God by Jonathan EdwardsMosharraf Hossain Sylar100% (1)

- Waiting For Godot and The Existential Theme of Absurdity 2 PPDocument3 pagesWaiting For Godot and The Existential Theme of Absurdity 2 PPMosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)