Professional Documents

Culture Documents

SSM Kalipeni 2000 Health and Disease in Southern Africa

Uploaded by

Maria ŢeneCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

SSM Kalipeni 2000 Health and Disease in Southern Africa

Uploaded by

Maria ŢeneCopyright:

Available Formats

Social Science & Medicine 50 (2000) 965983

www.elsevier.com/locate/socscimed

Health and disease in southern Africa: a comparative and vulnerability perspective

Ezekiel Kalipeni*

Department of Geography, 220 Davenport Hall, MC150, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 607 South Mathews Avenue, Urbana, IL 61801, USA

Abstract Using a vulnerability and comparative perspective, this paper examines the status of health in southern Africa highlighting the disease complex and some of the factors for the deteriorating health conditions. It is argued that aggregate social and health care indicators for the region such as life expectancy and infant mortality rates often mask regional variations and intra-country inequalities. Furthermore, the optimistic projections of a decade ago about dramatic increases in life expectancy and declines in infant mortality rates seem to have been completely out of line given the current and anticipated devastating eects of the HIV/AIDS pandemic in southern Africa. The central argument is that countries experiencing political and/or economic instability have been more vulnerable to the spread of diseases such HIV/AIDS and the collapse of their health care systems. Similarly, vulnerable social groups such as commercial sex workers and women have been hit hardest by the deteriorating health care conditions and the spread of HIV/AIDS. The paper oers a detailed discussion of several interrelated themes which, through the lense of vulnerability theory, examine the deteriorating health care conditions, disease and mortality, the AIDS/HIV situation and the role of structural adjustment in the provision of health care. The paper concludes by noting that the key to a more equitable and healthy future seems to lie squarely with increased levels of gender empowerment. # 2000 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Infectious disease; HIV; Vulnerability theory; Southern Africa

Introduction In spite of the raging AIDS epidemic, recent research in the eld of health care in sub-Saharan Africa indicates that major improvements in health have been achieved in some countries since independence (Boerma, 1994). Although still high by world standards, infant mortality rates in sub-Saharan Africa have declined from 145 per 1000 live births in 1970 to 104 per 1000 in 1992. Other statistics such as increases

* Tel.: +1-217-333-1880; fax: +1-217-244-1785. E-mail address: kalipeni@uiuc.edu (E. Kalipeni).

in life expectancy, declines in maternal mortality, wide spread immunizations of children have been oered as a success in the ght against disease in a number of countries in southern Africa, notably Malawi, Zimbabwe, Botswana and South Africa. Nevertheless, these gures mask the worsening situation in parts of the region that are still plagued by political and economic instability. For example, Angola and Mozambique went through a 30 year period of civil war while Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe have experienced economic problems engendered partly by the imposition of the World Bank structural adjustment programs. A set of complex factors, both internal and external, have exacerbated poverty and disease, nota-

0277-9536/00/$ - see front matter # 2000 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved. PII: S 0 2 7 7 - 9 5 3 6 ( 9 9 ) 0 0 3 4 8 - 2

966

E. Kalipeni / Social Science & Medicine 50 (2000) 965983

bly war, economic crisis, servicing of debt, government corruption and world commodity prices. These and many other factors have contributed signicantly to the vulnerability of nations and the populace in this region resulting in poor health conditions. Challenges in the provision of and access to health care are immense. As the World Bank (1994); Graham (1991) note, the maternal mortality rate at 700 deaths per 100,000 live births for the region and the continent as a whole is double that of other low- and middleincome developing countries and more than 40 times greater than in the industrial nations. This paper examines the status of health in southern Africa highlighting the disease complex and some of the factors for the deteriorating health conditions. A discussion of all the factors, given the limited nature of space for an article, is impossible. It is argued that aggregate social and health care indicators for the region such as life expectancy and infant mortality rates often mask regional variations and intra-country inequalities. Furthermore, the optimistic projections of a decade ago about dramatic increases in life expectancy and declines in infant mortality rates seem to have been completely out of line given the current and anticipated devastating eects of the HIV/AIDS pandemic in southern Africa. The central argument is that countries experiencing political and/or economic instability have been more vulnerable to the spread of diseases such HIV/AIDS and the collapse of their health care systems. Similarly, vulnerable social groups such as commercial sex workers, women and children, and schoolgirls have been hit hardest by the deteriorating health care conditions. The paper is divided into several interrelated sections which, through the lense of vulnerability theory, examine the deteriorating health care conditions, the ecological context of disease, mortality, the AIDS/HIV situation and the role of structural adjustment in the provision of health care. Sources of data and problems In this paper we use data from various sources. The most important two sources of information are the Human Development Report produced by the United Nations Development Programme and Country Epidemiological Fact Sheet on HIV/AIDS and Sexually Transmitted Diseases by UNAIDS. Other sources include Country Health Statistics Report by the Center for International Health Information in the United States and, wherever available, specic national health statistics. The data need to be used with caution. Most data on country-wide rates of HIV/AIDS, for example, are extrapolated from small study samples, usually of pregnant women seeking prenatal care or those with STD's seeking clinical care. How representative these

samples are is questionable, yet it is the only data available for most southern African countries. There are numerous problems with these data. Due to gaps in diagnosis, under-reporting, and reporting delays, ocially reported AIDS and other diseases represent only a portion of all cases in a country. Completeness of reporting varies substantially from one country to another, from less than 10% in some countries with fewer resources, to more than 80% in most industrialized countries. For example, Oppong (1998a,b) notes that some African governments may conceal the real dimensions of the AIDS problem out of a sense of shame and concern that the real gures would drive investors and tourists away. Mortality and other health care indicators are also problematic. In the African setting (as in the case for almost every developing country), mortality data are often inaccurate and incomplete. The potential errors and biases resulting from such data make any meaningful analysis almost impossible. One cannot therefore compute error ranges or condence intervals using such statistics. Although national data may not reect the current situation of health and disease, they can, nevertheless, be used to oer insights into general trends such as regional cross-country variations. Recently small but soundly designed sample surveys have begun to yield important statistics enabling cross country comparisons. An example of these surveys are the Demographic and Health Surveys of the late 1980s and the early 1990s. The vulnerability perspective Watts and Bohle (1993) propose a tripartite explanation of vulnerability theory consisting of entitlement, empowerment and political economy. These two authors state that ``Our tripartite causal structure denes the space of vulnerability through the intersection of these three causal powers: command over food (entitlement), state-civil relations seen in political and institutional terms (enfranchisement/empowerment), and the structuralhistorical form of class relations within a specic political economy''. Oppong (1998a,b), in applying vulnerability theory to Ghana's HIV/AIDS situation, points out that adverse life circumstances such as hunger and disease do not aect social groups uniformly. Oppong further argues that while all human beings are biologically susceptible to infection by dierent diseases such as HIV/AIDS, certain social and economic factors place some individuals and social groups in situations of increased vulnerability. In short, the vulnerability perspective deals with issues of dierential access to resources. Furthermore, this perspective can be applied to suites of nested localregionalglobal processes such as

E. Kalipeni / Social Science & Medicine 50 (2000) 965983

967

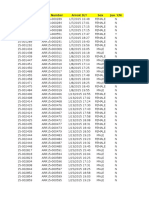

Table 1 Demographic and health indicators, 1994

Current demographic situation For the purposes of this paper the following countries are considered to be part of the southern African subcontinent: South Africa, Botswana, Swaziland, Namibia, Zimbabwe, Lesotho, Zambia, Angola, Malawi and Mozambique. As of 1994, estimates indicate that the combined population for these countries was about 102 million people. The country specic distribution of this population ranged from a low of 0.8 million for Swaziland to 40.6 million for

Maternal mortality rate (per 100,000 live births)

health. In embracing this perspective, we dene health in a very general sense as ``a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or inrmity'' (Mead et al., 1988). In order to understand better the workings of vulnerability theory, let us look at the HIV/AIDS prevention eorts in Africa. As Packard and Epstein (1991) note, to encourage eorts to combat the spread of HIV/AIDS through sex education, just like eorts to control population growth in Africa through birth control, or tuberculosis through segregation, is to work against strong social, political and economic forces, and not simply culturally determined patterns of behavior. The general ineectiveness of AIDS prevention programs in Africa does not just stem from lack of funding, but from an unwillingness to look beyond simplistic approaches that focus on the peculiarities of individual sexual behavior rather than the social, economic, and political contingencies which make certain social groups such as commercial sex workers vulnerable. The reality of sexual behaviors is much more complicated. Poverty is one factor that limits the number and amount of resources available and gender is another (Kalipeni and Craddock, 1998). As Kalipeni and Craddock (1998) argue, for women in particular, jobs are scarce, resources such as government training projects or agricultural extension services are directed toward men, and local income-earning opportunities are generally unavailable. Scarce job opportunities for men mean that migrancy is high among many subSaharan countries as jobs are sought in neighboring countries or in far away regions from the home country. The result is that prostitution is the only income-earning occupation open to many women who must nd a way to feed not just themselves but their children in the absence of their husband's or any other means of support. In short, vulnerability, whether it be that of an individual or a country has a lot to do with the well-being of members of society. Individuals in certain social groups are more vulnerable than others. Poorer countries can ill aord the provision of employment and health care facilities. This theme will be used to guide the discussion in this paper.

Population per doctor Total population (millions) Crude death rate Crude birth rate Total fertility rate AIDS rate (cases per 100 people) One-year-olds fully immunized against measles tuberculosis Infant mortality (per 1000 live births) Country

South Africa Botswana Swaziland Namibia Zimbabwe Lesotho Zambia Angola Malawi Mozambique

230 250 370 570 610 940 1500 560 1500

51 55 72 63 70 79 110 120 147 116

95 81 94 95 59 63 40 91 58

76 68 69 74 74 69 32 70 40

12.91 25.10 18.50 19.94 25.84 8.35 19.07 2.12 14.92 14.17

4.0 4.7 4.7 5.1 5.1 5.1 5.8 7.2 7.1 6.5

30.7 36.6 38.5 37.0 40.5 36.5 43.4 50.7 50.2 45.0

8.6 11.8 10.1 11.9 14.4 11.1 18.5 18.5 22.7 18.6

40.6 1.4 0.8 1.5 10.9 2.0 7.9 10.5 9.6 16.6

4762 9091 4545 7692 25,000 11,111 50,000 33,333

968 Human development index value

E. Kalipeni / Social Science & Medicine 50 (2000) 965983

Zaire (Table 1). South Africa alone contains 40% of the total population of this region. Population growth rates also vary considerably from country to country but are generally on the higher end in comparison to the global population growth rate of 1.8% per annum. For example, the annual rate of natural increase ranges from 2.4% for South Africa to 3.7% for Zambia. It is interesting to note that the countries with the highest population densities (Malawi, Lesotho and Swaziland) are also the most heavily dependent on agriculture. Considering the widespread shortage of cultivable land, the low productivity of the farming techniques employed by most of the smallholder farmers in the region, and the rising costs of living, many of the people living in this region are nding it increasingly dicult to make a decent living (Zulu, 1996). In terms of fertility, South Africa has the lowest total fertility rate (4.0) while Malawi has the highest rate (7.1). Zimbabwe and Botswana, the two countries in the region with evidence of rapidly declining fertility rates, have total fertility rates of 5.1 and 4.7, respectively. Although most of the countries in this region have experienced substantial declines in mortality, mortality rates are still very high by world standards. Infant mortality is lowest in South Africa (51) and highest in Malawi (147). In Angola, Mozambique and Zambia infant mortality rates exceed 100. Botswana has the second lowest infant mortality rate (55), followed by Swaziland (63), Lesotho (79) and Zaire (94) (See Tables 1 and 2). Maternal mortality rates are also alarming for some of the countries in this region, for example Angola and Mozambique have a maternal mortality rate of 1500 deaths for every 100,000 live births. Other countries have maternal mortality rates, which range from a low of 230 for South Africa and a high of 940 for Zambia. In short, there is tremendous diversity in the demographic and socioeconomic experiences of countries in the southern African region. It should be noted that the indicators of development, which are given at the national level, mask intra-country diversity between regions and between rural and urban areas. In short, the southern African subregion is far from being homogeneous and one cannot simply overgeneralize the demographic and health experiences of countries in this region. Some countries seem to be well on their path to an irreversible socioeconomic and demographic transition while others continue to experience diculties in resuscitating their ailing economies and health care delivery systems. For example, Botswana, Zimbabwe, South Africa and Namibia have the most favorable demographic, socioeconomic and health care indices, while Angola, Malawi and Mozambique are at the bottom of the scale (see Tables 1 and 2). As shown in Table 1, South Africa has the lowest infant mortality rate, maternal mortality rate, total fertility rate

GDP index Education index Life expectancy index Real GDP per capita Adult literacy rate (%) Table 2 Indicators of human and economic development for southern African countries, 1994 Life expectancy at birth (years) HDI rank within Southern Africa HDI rank globally, (175 nations) Country

Angola Botswana Lesotho Malawi Mozambique Namibia South Africa Swaziland Zambia Zimbabwe

157 97 137 161 166 118 90 114 143 129

9 2 6 10 11 4 1 3 8 5

47.2 68.1 57.9 41.1 46.0 55.9 63.7 58.3 42.6 49.0

42.5 98.0 70.5 55.8 39.5 40.0 81.4 75.2 76.6 84.7

1600 2726 1109 694 986 4027 4291 2821 962 2410

0.37 0.72 0.55 0.27 0.35 0.52 0.64 0.55 0.29 0.44

0.39 0.90 0.66 0.60 0.35 0.55 0.81 0.74 0.67 0.68

0.25 0.43 0.17 0.10 0.15 0.65 0.69 0.45 0.14 0.38

0.335 0.684 0.457 0.320 0.281 0.570 0.716 0.582 0.369 0.500

E. Kalipeni / Social Science & Medicine 50 (2000) 965983

969

and the highest immunization rates against tuberculosis and measles. South Africa is followed by Botswana, Namibia and Zimbabwe. The distinguishing feature of these countries from the rest of the other countries in this region is their relative economic strength. Deteriorating health care conditions After independence, governments in the region have attempted to provide biomedicine to everyone, focusing on hospitals, dispensaries and medical schools centered in urban areas to the neglect of rural areas. Biomedical health facilities have typically been based in urban settings beyond the reach of many rural dwellers. To obtain formal biomedical health care, rural residents have to travel long distances sometimes on foot to urban centers where they have to endure a long wait before nally seeing a biomedical practitioner (Oppong, 1998a,b). The inconvenience and hassles involved, particularly when patients are illiterate and unable to communicate meaningfully with doctors are formidable. The strange and usually impersonal cultural environment in which biomedical services are provided frequently leads to patients vowing not to repeat the experience (Kalipeni and Kamlongera, 1996; Oppong, 1998a,b). In a village level study of primary health care in Malawi, Kalipeni and Kamlongera (1996) revealed that villagers were unwilling to use modern health care facilities for a variety of sociocultural reasons. Among the problems the villagers identied were the long distance walk to the clinic spending the whole day to get to such facilities only to nd the medical superintendent out or to nd relatively unhelpful personnel as pressure of work often led them to make snap and unhelpful diagnosis. Some of the villagers found such centers both imposing and threatening. In recent years, increasing deterioration in the economy has meant little money for maintaining existing health infrastructure. Countries such as Malawi and Zambia have been hardest hit by the economic crisis which began in the early 1980s and was exacerbated by the imposition of structural adjustment programs which we discuss in greater detail later in this paper. Cutbacks in health expenditure have resulted in large layos, signicant salary reductions (due to ination), and closure of many facilities (Falola, 1992). Most health workers have been compelled to take second jobs to make ends meet, resulting in absenteeism and poorer health care. For example, in Zambia, the departure of a large number of expatriate doctors due to declining economic conditions in the late 1980s and early 1990s has created a wide gap in the availability of doctors, particularly in the Copperbelt and Southern provinces (Kloos, 1994; Akthar and Nilofar,

1994). In addition, because of poor conditions of service, even Zambian doctors are leaving the country for Zimbabwe, Botswana and other countries of southern Africa. In Malawi the health care situation has become desperate with severe scarcities of medicines in government hospitals and health centers throughout the country. One expatriate doctor working at a hospital in northern Malawi recently lamented (McCracken, 1998, communication on NYASANET): F F F the hospital stays busy here, still mostly with malaria, malnutrition and AIDS, the big three for us as well as complicated obstetrics of course. We hear that there is bubonic plague or some close cousin to it down in Kasungu with 110 cases reported but no deaths. We have a team of malaria experts here rather unexpectedly studying our Fansidar resistance which is rather depressingly (but not too surprisingly) at 10% F F F We have been out of Bactrim and Tylenol and chloroquine for two months and this morning ran out of alcohol so the lab guys are using a paran lamp to dry the slides F F F A recent newspaper article notes the following conditions at Lilongwe Central Hospital, one of the two major hospitals in Malawi (Wakin, 1998): The patients lie two to a bed and on the oor, waiting to be sent home to die. Tattered blankets brought by relatives drape their shrunken bodies, because Lilongwe Central Hospital doesn't have any linen. The sounds of sawing and hammering in the streets testify to the booming business done by the capital's conmakers. Public oces grind to a halt because so many workers are away at funerals. Businesses are crippled when key employees die. To try to counter the growing scarcity of medications and the deteriorating health care delivery system, most governments have began to introduce user charges. Dubbed as the ``Bamako Initiative'' African ministers of health met in September of 1987 in Bamako, Mali, and decided to introduce a small fee for health care services for cost recovery purposes. However, concerns have been raised about the deleterious eects on health care utilization which has been noted in many instances where user charges or cost recovery attempts have been introduced (Kloos, 1994). For example, when Swaziland imposed user fees, attendance at health facilities declined by 32% in government facilities and 10% in mission clinics. Furthermore visits for childhood vaccination and treatment of sexually transmitted diseases fell by 17% and 21% respectively (McPake, 1993). In Angola and Mozambique health care facilities

970

E. Kalipeni / Social Science & Medicine 50 (2000) 965983

were drastically aected by the prolonged civil wars during the 1970s and 1980s. During the civil war many peripheral health units were destroyed which represented 31% of the total primary health care network in these countries (United States Committee for Refugees, 1987). Although in the postwar period many health posts have been reopened and expansion has continued, the overall eect has been to halt the previous rapid expansion in the number of peripheral health units. Patients in hospitals were sometimes massacred which scared most sick people away from hospitals. By 1987 over 4 million Mozambicans had lost access to health care facilities as a result of direct destruction, looting and forced closure of health units, displacement of people and kidnaping of health care workers. Health and the ecological context of disease The physical and ecological structure of southern Africa is as varied as the population densities and demographic characteristics. The altitude ranges from 0 to over 2000 meters above sea level. Several major biomes characterize this region including tropical rainforests in Zaire, patches of montane forest, moist and dry savanna, semidesert and desert conditions, and temperate grasslands (see Stock, 1995, p. 37). The political environment, poverty and the generally low levels of well-being for the majority of the people in this region combine with the varied climatic conditions, vegetation and biogeography to explain the prevalence of disease-causing organisms, or pathogens, such as bacteria, viruses and worms (Kloos and Zein, 1993). Indeed, in most parts of southern Africa the main causes of mortality continue to be infectious and vectored diseases such as tuberculosis, measles, malaria and others. One of the major causes of infant and childhood mortality and general morbidity in this region is malaria which is also responsible for many stillbirths and babies born underweight (Bradley, 1991). Malaria is a problem that appears to be worsening in much of southern Africa. The increase in malaria is attributed to the collapse (owing to managerial, institutional and nancial constraints) of the malaria control programs in many countries, together with the increasingly widespread resistance of malaria vectors to the available insecticides and of malaria parasites to the available chemoprophylactic agents (Bradley, 1991; Oppong, 1997).Today almost all countries in southern Africa have chloroquine-resistant Plasmodium falciparum, the most common and lethal of the malaria parasites. Schistosomiasis is another debilitating and widespread environmental disease which leads to chronic ill health. In southern Africa malaria and schistosomiasis can be

thought of as gender biased diseases in that women who are mostly in contact with water through their daily household chores of washing and cooking are likely more vulnerable than men. Malaria is also likely to be fatal among those who are undernourished, and women and children are most likely to be undernourished. Stock (1995) notes that the resurgence of malaria throughout Africa is partly attributable to the decline in nutritional status among the poor in both urban and rural areas. For a discussion of the pathophysiology of malaria and schistosomiasis (see Bradley, 1991; Walker, 1994; Ikinger, 1994). The most troubling and recent scourge to hit the population of southern Africa is the AIDS pandemic. As shown in Table 1, Namibia, Zimbabwe and Botswana stand out in AIDS rates among the adult population. Recent estimates from UNAIDS indicate that 26% of Zimbabwe's adult population (i.e. those aged 1549) are HIV seropositive. This is followed by Botswana (25%), Namibia (19%) and Zambia (19%). Malawi, Mozambique, South Africa and other countries have rates of above 10%. The AIDS epidemic is creating a major health crisis. Medical systems, already overwhelmed by the numerous tropical diseases, cannot cope with this new and massive onslaught of AIDS cases. The disease could reverse the little development that has so far been attained by a number of countries in this subregion. It will have major socioeconomic and demographic consequences. Some projections show that if current AIDS/HIV infection rates continue, life expectancies could decline to less than 30 years, and infant and adult mortality rates will begin to take an increasing trend in the rst decade of the 21st century (Kalipeni, 1995; Becker, 1990). Of concern here is the tragic negative impact of this disease on the lives of many women in this region. The impact of the pandemic on women and children will be discussed in greater detail in a later section on AIDS in southern Africa. The above are a few of the many diseases people in this region have to contend with in the face of declining health care services. Other preventable diseases such as tuberculosis, cholera, tetanus, respiratory infections, diarrheal diseases, measles, pneumonia, anaemia, nutritional deciencies, etc. continue to take precious infant and adult lives. It has been estimated that perinatal infections and parasitic illnesses are responsible for 75% of infant deaths and 71% of childhood deaths in Africa (Feachem and Jamison, 1991). Feachem and Jamison (1991) suggest that an African child has a 10% chance of suering from diarrhea on any given day and a 14% chance of dying from a severe episode. This is signicant since diarrhea accounts for 25% of all childhood deaths world-wide and 37% of all childhood deaths in sub-Saharan Africa, being one of the foremost causes of poor health and childhood mor-

E. Kalipeni / Social Science & Medicine 50 (2000) 965983 Table 3 List of ten leading causes of out-patient attendances for morbidity, Malawi and South Africa Disease condition Malawi 1989 Malaria Respiratory system Abdomen and gastro intestinal tract Conditions of the skin Other diarrhoeal diseases Inammatory disease of the eye Traumatic conditions Sexually transmitted disease Symptoms referable to limbs and joints Hookworm and other helminthiasis South Africa 1991 Tuberculosis (all forms) Measles Malaria Viral hepatitis Typhoid fever Meningococcal infection Food poisoning Trachoma Tetanus Rheumatic fever Cases 3,744,876 1,934,132 777,005 658,982 538,021 483,009 439,253 351,957 305,962 290,663

971

Rate per 100,000 people 44,020 22,730 9,130 7,750 6320 5680 5160 4140 3600 3420

80318 10622 6822 2639 2146 926 502 325 117 83

215.3 28.5 18.3 7.1 4.7 2.5 1.4 0.9 0.3 0.2

Souces: Malawi Government (1989); Department of National Health and Population Development, South Africa (1991).

tality in this part of Africa. In southern Africa recent demographic and health survey (DHS) data indicate that 2040% of children suer from attacks of diarrhea characterized by cramping, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and often death (Katjiuanjo et al., 1993; Gaise et al., 1993; National Statistical Oce, 1994; Lesetedi et al., 1989).

Health and mortality change A recent World Bank study notes that health in subSaharan Africa has improved dramatically in the decades since independence (World Bank, 1994). Infant mortality rates have declined by one-third from a high of 145 infant deaths per 1000 live births in 1970 to 104 per 1000 in 1992. The mortality rate for children under ve years fell 17% between 1975 and 1990. In Botswana and Zimbabwe, for example, the under-ve mortality declined by 41% between the late 1970s and the late 1980s. Adult mortality rates have also seen major declines during the postindependence era in most countries of southern Africa. Life expectancy at birth is currently estimated to be 52 for men and 55 for women and has increased approximately by 4 years every decade since the 1950s (African Development Bank, 1992; Population Reference Bureau, 1992). The

crude death rate has declined to a very low level of 13 deaths per 1000 population for the whole region. In spite of these gains, challenges in the provision of and access to health care are immense. Furthermore, the validity of the statistics need to be questioned as indicated earlier in the section on data. When data is disaggregated by rural and urban, stratied sample surveys taken from southern Africa have shown infant mortality rates in rural areas to be in the order of 250 to 300 per 1000 live births whereas some urban areas have rates as low as 50 infant deaths per 1000 live births (see for example, National Statistical Oce, 1991; Lesetedi et al., 1989). There is therefore great intra-country variations making regional aggregate measures virtually meaningless. The risk of death remains markedly higher at all ages in southern Africa than in other parts of the world. Life expectancy at birth is 4 years less than in southern Asia and 14 years less than in Latin America (Population Reference Bureau, 1992). Among the countries in the world where life expectancy in 1990 was lower than 50 years, ve were in southern Africa (UNDP, 1997). Infant and childhood mortality are generally higher than in any part of the world. In certain countries that have endured deteriorating economies during the last decade, child mortality levels are virtually identical to those prevailing ten years ago. For example, one of the

972

E. Kalipeni / Social Science & Medicine 50 (2000) 965983

Fig. 1. Age/sex death rates by gender, Malawi 1987. Source: author, data from National Statistical Oce (1991).

most striking ndings from the Zambia Demographic and Health Survey of 1992 was the apparent downturn in child survival prospects over the 1980s decade. From 1977 to 1991, under-ve mortality rose by 15% from 152 to 191 per 1000 live births. Much of this increase resulted from an increase in mortality under the age of one year. Both neonatal and postneonatal mortality increased by 35% in the 15-year period before the survey. In this same period child mortality increased by 20% (see Gaise et al., 1993, p. 81). Similarly in countries such as Angola and Mozambique infant, childhood and adult mortality rates increased as a result of prolonged civil war and subsequent economic downturns. Using morbidity statistics as a measure of health, the leading causes of morbidity in Malawi and South Africa, for example, are infectious and communicable diseases. Table 3 illustrates that relatively few diseases are responsible for the bulk of adult and infant morbidity and mortality. In Malawi malaria and symptoms referable to the respiratory system account for a considerable proportion of leading causes of out-patient attendances. In South Africa, tuberculosis, measles, and malaria rank at the top respectively. An excellent example of vulnerability is given by the inequitable access to health care resources in South Africa as discussed below.

It has been reported that African women of reproductive age have the highest death risk from maternal causes of any women in the world (Paul, 1993; Boerma, 1987). Boerma concludes that national levels of maternal mortality in sub-Saharan Africa most likely vary from 250 to 700 per 100,000 live births. For the southern African subregion as shown in Table 1 the range is from 230 for South Africa to 1500 for Angola and Mozambique. On average the regional maternal mortality rate is 740 which is above the African average of 700. In industrialized countries women live on average 7 years longer than men due to an inbuilt biological superiority for women (Santow, 1996). As a matter of fact the dierence in life expectancy is consistently greater for women at all ages in developed countries. On the other hand, in developing countries a disadvantage accrues to women from their double burden of household production and reproduction which results in high maternal mortality rates due to complications of pregnancy and childbirth (Homan et al., 1987). Two micro-level studies by Cunnan (1997); Moodley and Zama (1997) show the precarious position of women in South Africa as far as socioeconomic and health status of black women in the neglected sections of urban areas are concerned. The discussion in these two studies demonstrates that in peri-urban settlements women suer from numerous

E. Kalipeni / Social Science & Medicine 50 (2000) 965983

973

Fig. 2. Life Expectancy by gender, 1994. Source: author, data from UNDP (1997).

illnesses as a result of their productive, reproductive and social roles. These illnesses, combined with low socioeconomic conditions, high workloads and the lack of adequate health services are detrimental to the health status of women and overall economic development. In southern Africa insights into the actual dierences between the health of women and men can be gained by comparing sex dierentials in mortality of countries that are in dierent stages of development. In Malawi where life expectancy is shorter, sex dierentials in mortality are less pronounced, particularly in the childbearing age range (see Fig. 1). The most marked divergence between women and men can be seen after age 50 with women experiencing lower mortality. For a low income country like Malawi, during the childbearing age range women experience similar mortality to men due to the greater risks associated with reproduction. This is also true of other low income countries in this region such as Angola, Mozambique and Zambia. On the other hand an examination of a country such as South Africa shows slightly larger sex dierentials in favor of women. But even in South Africa one has to take into consideration the great inequality in access to health services with the better-o (mainly the white

population) enjoying access to a private health service comparable to that of a developed country. For example, if we use maternal mortality and infant mortality rates by race, Africans registered a maternal mortality rate of 58 and infant mortality rates of 52; the colored population has a maternal mortality rate of 22 and an infant mortality rate of 35; and the white population has a maternal mortality rate of 8 and an infant mortality rate of 9 (Department of National Health and Population Development, 1991). Dierences in life expectancy also support the assertion that economically better-o countries in the region are beginning to show a growing gap between the life expectancies of women and men in favor of women. Countries at the bottom of the economic development ladder like Malawi and Mozambique show a small dierence in life expectancy between men and women (see Fig. 2). This nding also holds true in other parts of Africa. A recent study by Klasen (1996) gives evidence of large, and, in some parts, rising mortality disadvantages for women and girls which have been traced to the intra-household allocation of resources. Explanations for these dierentials lie in the double burden of household chores, nutritional in-take and access to health care resources. As Santow (1996);

974

E. Kalipeni / Social Science & Medicine 50 (2000) 965983

Svedberg (1990) point out, one way in which gender distinctions are maintained and reinforced is through dierential allocation of food. It is quite common for women to eat less, and less well, than men. The high fertility rates in the region even in those countries where fertility has begun to decline, means that women have to undergo frequent pregnancies and birth which take a toll on their health status. The AIDS pandemic More recently there has been an explosion of AIDS in southern Africa which is transmitted heterosexually. A number of countries in this subregion have been hardest hit including Malawi, Zimbabwe, Namibia and Botswana (see Table 1). Staneck and Way (1996) note that repeated HIV seroprevalence studies of pregnant women conducted in African countries generally show a consistent and rapid increase in HIV seroprevalence. For example, in Botswana, HIV seroprevalence increased from less than 10% to more than 30% in Francistown and from 6% to 19% in Gaborone between 1990 and 1993 (Staneck and Way, 1996, p. 43). In the following paragraphs, I use Malawi to highlight salient features of the AIDS pandemic in southern Africa. Current estimates for Malawi, indicate that about 1 in every 7 Malawians is HIV positive and that certain sectors of the population (e.g. commercial sex workers, pregnant women, truck drivers and soldiers) have alarming HIV infection rates. Small surveys conducted in the early 1980s indicated a 2% HIV positive rate in otherwise t pregnant women in ante-natal clinics, and in blood donors (King and King, 1992). In the case of pregnant women, this gure rose dramatically to 8% in 1987, 19% in 1989, 23% in 1990 and is currently estimated to be about 35% (Reeve, 1989; Kristensen, 1990; Kool et al., 1990; King and King, 1992; Namanja et al., 1993; Bloland et al., 1995). Although the data has to be used with caution due to issues of reliability, representativeness and quality, there is sucient evidence to suggest that within a very short period the disease has rapidly diused throughout southern Africa. In Malawi, the cumulated number of reported fully blown AIDS cases has also exploded from almost zero in 1985 to 480,000 AIDS cases in 1998 (UNAIDS, 1998). One must keep in mind that this is a gross underestimate of the true magnitude of the disease since the data is based on hospital cases and that most people do not go to hospitals. From a geographic point of view, throughout southern Africa and Africa in general, urban areas have been hit hardest by the epidemic in comparison to rural areas (see Gordon, 1996). Estimates compiled from blood donors, women coming to ante-natal

clinics, and people undergoing testing when applying for life insurance reveal that well over 30% of the adult population in the major urban areas of Blantrye and Lilongwe may have been infected by the virus (Miotti et al., 1992). While urban areas lead in rates of infection, it must be pointed out that the disease is spreading rapidly in rural areas propelled by rural urban linkages and the disadvantaged position of rural areas in terms of knowledge about this disease. Rural and urban areas in Malawi and elsewhere in Southern Africa are closely intertwined with a constant two-way ow of people facilitating the HIV/AIDS exchange. In addition, rural Malawi has traditionally sent thousands of its young men to the mines of South Africa to work on two to three year contract arrangements. Upon their return to Malawi, these migrant workers spend a week or so in the cities of Blantyre and Lilongwe having a `good time' before going back to their home villages in the country-side (Kalipeni, 1995). It is estimated that nearly half of the mine workers returning to the rural areas of the country after a work stint in South Africa are infecting their wives and other women (Gould, 1993). Indeed, the rapid diusion of the disease in this region has been ascribed to a high level of `sexual mobility' to such factors as men's premarital and extramarital sexual activity during frequent work-related absences from home, institutionalized prostitution in the towns, the lack of other economic opportunities for divorcees and widows and polygyny and related postpartum sexual abstinence for wives not for husbands (Carael, 1996; Campbell, 1997). In fact conventional prevention measures including education are ill-focused because they do not deal with poverty and vulnerability. As Oppong (1997) argues, expecting people to abandon behaviors that bring pleasure and immediate gratication is unreasonable, especially when it gives them power or income, even while posing unacceptable risks to personal, family and community health. People should be rewarded with tangible benets, not penalized through loss of income, for changing unacceptable behavior. Providing opportunities for young women to prevent them from turning to prostitution for economic survival may be as important as any educational measure in the ght against AIDS (Oppong, 1997). Indeed we concur with Oppong that without such a reorientation in focus, we may very well be ghting a losing battle with AIDS in Africa. In as far as gender is concerned, data compiled by UNAIDS shows some interesting trends in the age and sex distribution of AIDS cases in southern Africa (UNAIDS 1998). The age and sex distribution in both rural and urban areas are quite similar. The majority of the AIDS cases are in the 2049 age group. The lowest rates are in the 514 age range. The 04 age

E. Kalipeni / Social Science & Medicine 50 (2000) 965983

975

Fig. 3. Age/sex distribution of AIDS cases in Malawi, Lesotho, Zimbabwe and South Africa 1998. Source: author, data from UNAIDS (1998).

976

E. Kalipeni / Social Science & Medicine 50 (2000) 965983

Fig. 3 (continued)

E. Kalipeni / Social Science & Medicine 50 (2000) 965983

977

group shows signicantly higher numbers of infection, an indication that infants are being infected either in the womb before birth or while being taken care of by infected mothers (see Fig. 3). As shown in Fig. 3, the age/sex pattern of Malawi matches that of other southern African countries such Botswana, Zimbabwe and South Africa. One interesting trend in the data is that women appear to be exposed to the disease at earlier ages than men. For example, there is a preponderance of females in the age range 1524 while men are slightly more predominant in the age groups above 30 years. A set of complex but interrelated factors have been advanced to explain the age mismatch. First, there is the ``Sugar Daddy'' phenomenon which has been noted as a plausible explanation for the age/sex mismatch. Researchers elsewhere in Africa frequently reveal one particularly insidious aspect of the pandemic, namely, older men going for schoolgirls. As middle aged men have began to realize the real and quite personal danger of intercourse with their usual ``girlfriends'', they are enticing young girls 1015 years of age, hoping that this age range may be relatively free of infection. The agesex disparities shown in Fig. 3 for Malawi, Lesotho, Zimbabwe and South Africa seem to support this assertion. It must be noted however, that the sex and age distribution of AIDS cases in the above countries and others in the region, cannot be simply attributed to the ``sugar daddies'' although they clearly have a role and issues of `blame' within the sugar daddy context are complex. Here vulnerability theory can help to shed some light on the age/sex mismatch. As noted earlier, scarce job opportunities for men mean that migrancy is high among many sub-Saharan countries as jobs are sought in neighboring countries or in far away regions from the home country. The result is that prostitution is the only income-earning occupation open to many women who must nd a way to feed not just themselves but their children in the absence of their husband's or any other means of support. First there is the issue of poverty and single motherhood for many women. Younger unmarried women with children and meager means to support their families engage in sexual relations with older married men out of necessity. These women are powerless to force men to use condoms. In surveys and interviews conducted in Malawi, Zimbabwe, Botswana and elsewhere in the region, the theme of constrained action by women within sexual exchanges repeats itself. That is, women do not always have the choice to make their partners wear condoms. Furthermore, women who are economically dependent upon their partners, whether in marriage or as commercial transactions, do not under most circumstances have the power to insist upon condom use. As Oppong (1998a,b) argues, for poor women forced by hardship into commercial sex work, behavior change does not

come simply through education and dissemination of information; it comes through empowerment providing opportunities to enable them secure respectable livelihoods. Thus the age/sex mismatch might indicate the vulnerability of both school girls via the sugar daddy context and poor women via unequal power relations in sexual exchange with older men of means. As a matter of fact, the discussion of economic factors and AIDS is also far more complicated than suggested above, particularly as in many countries the prevalence amongst the better educated and wealthier is quite high. This can be explained in that the better educated and wealthier men have the means to prey on the younger poverty stricken females, transferring the virus to their wives and others such as school going girls. Thus, increased condom availability would do nothing to change these power dynamics and neither would increased education about HIV transmission, or encouragement of couple delity (Kalipeni and Craddock, 1998). The end result is that throughout the region, the ratio of female to male cases is rising with women at greatest risk of infection.

Structural adjustment, vulnerability and health As pointed out earlier, in a recent book by the World Bank titled Better Health in Africa: Experience and Lessons Learned, the fact that major improvements in health have been achieved in Africa in the years since independence is highlighted, noting the dramatic declines in the infant mortality rate from 145 per 1000 live births in 1970 to 104 per 1000 in 1992. Other statistics such as increases in life expectancy, declines in maternal mortality, wide spread immunizations of children are oered as a success in the ght against disease throughout the African continent in the postindependence era. But these gures mask the gleam reality of a worsening situation in southern Africa. In spite of the remarkable gains, the World Bank in this study acknowledges that challenges in the provision of and access to health care are immense. The risk of death remains markedly higher at all ages in Africa than in other parts of the world, more so in the case of women and children. What the World Bank study fails to note is that in certain countries that have endured deteriorating economies during the last decade, child mortality levels are virtually identical to those prevailing ten years ago. The book seems to lay the blame squarely on African governments for the deteriorating health care infrastructure noting the ineciency and waste in the supply of drugs and other health related services. In reading this book I found it ironic that the bank fails to be self critical in the evaluation of its programs, particularly the famous structural adjustment

978

E. Kalipeni / Social Science & Medicine 50 (2000) 965983

programs which seem to have caused more harm than good throughout the continent. As economies of poor southern African countries such as Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe failed in the 1980s, nancial and technical assistance from multilateral organizations such as the World Bank was conditioned by the World Bank's structural adjustment program (SAPs). The SAPs were initiated to adjust malfunctioning economies and promote greater economic eciency and economic growth to make subSaharan economies more competitive in today's global economy (Aryeetey-Attoh, 1997; Asthana, 1994). As Aryeetey-Attoh (1997) notes candidates for structural adjustment were those with budget decits, balance-ofpayment problems, high inationary rates, ineective state bureaucracies, inecient agricultural and industrial production sectors, overvalued currencies and inecient credit institutions. The SAPs have a number of features which have negatively aected the position of the urban poor, women and children. The major features include trade liberalization, government expenditure reduction, devaluation of currencies, reduction of controls over foreign currency and trade union restrictions among others. Evidence indicates that structural adjustment programs have had far reaching deleterious eects on health and social services throughout Africa. Living conditions for urban and rural populations have deteriorated, the educational infrastructure crumbled and the health care services are in dire straits (Potts, 1995; Lensink, 1996; Tevera, 1997). For example Lensink (1996) notes that with respect to Africa the number of people between the ages of 6 and 23 who received education decreased during the 1980s and the number of people per doctor and per nurse increased strongly. Generally adjustment programs have had dramatic negative eects on quality of care, health service utilization due to the imposition of user fees, search for alternative sources of health care, changes in mortality and morbidity and nutritional status. We have already touched on some of these issues and I will briey discuss the major ndings from southern Africa with reference to these issues. In many countries, even those that have stronger economies, governments have to reduce expenditure on health care. Tevera (1997) clearly demonstrates that in the course of the 1980s government funding for the health sector in Zimbabwe became inadequate for the provision of basic health services, and even more so for the support of community-based health care (Tevera, 1997). Zimbabwe is one of the few countries in southern Africa that managed to increase government health expenditure in real terms during the 1980s (Chabot et al., 1995). However, this policy of consistent real increases in public nancing of health services could not be sustained under the conditions of the

structural adjustment program that started in 1991. As a result, real per capita public expenditure on health dropped by a total of 35% between 1991 and 1994 (Chisvo and Munro, 1994). Tevera (1997) notes that the health sector in Zimbabwe has suered from across-the-board cuts in government expenditures since 1991 and that these cuts have reversed the upward trend in expenditure that had occurred since independence. The end result of the cuts in Zimbabwe's health care expenditure was a 10% decline in the number of nurses per person employed by the Ministry of Health and Child Welfare between 1991 and 1992 from more than 9 per 10,000 to just over 8 per 10,000 population. By mid-1992 about 800 health workers had been retrenched and 400 nursing posts had been abolished. This was followed by a substantial decline in the public funding of drugs and the imposition of user fees as part of cost-recovery. The stringent implementation of fee collection together with the requirement of advance payment, particularly for maternity care, has already had a deterrent eect in terms of utilization of government services in Zimbabwe (Tevera, 1997). Drugs are in short supply and their costs have increased sharply and are beyond the reach of most of the low income earners. Perhaps the most tragic consequence in Zimbabwe is a steady increase in deaths from diseases that in the past had been brought under control. This is in large part because of the indirect eects of structural adjustment on nutrition, unhealthy living conditions and poverty. Similar narratives can be told for health care delivery systems in Botswana, Malawi, Zambia, Zaire, Angola and Mozambique (see for example McPake, 1993). In Zambia poverty is now a major national problem where it is estimated that as much as 42% of the urban population lives below the poverty line (Kalumba, 1990). The price of basic commodities, such as chicken, have increased more than tenfold during the past decade, whereas in the same period wages only doubled. Studies suggest that the consumption pattern in poor households is changing from relatively protein and energy-rich food towards less expensive, bulkier foods, with a decreasing number of meals per day (Streeand et al., 1995). This process of impoverishment hits women harder than men, in particular because SAPs reinforce an already existing process of marginalization of women's production. Where SAPs lead to an increase in production, they stimulate the production of cash crops for export such as cotton, cocoa, tea, and coee often to the detriment of household consumption (Streeand et al., 1995). The increase in cash crop production, usually controlled by men, also leads to increase in workloads for female family members. Further, women must bear the brunt of the social con-

E. Kalipeni / Social Science & Medicine 50 (2000) 965983

979

sequences of adjustment measures. Since they are also responsible for social and health aspects within the family, it is they who must cope with the increased burden of disease and hunger. In short, structural adjustment programs have had a disproportionate impact on increasing their workload while often yielding very few benets health-wise and economically. There is growing evidence of the impact of structural adjustment on the health of mothers and infants. Costello et al. (1994) argues that most of the child mortality rates presented in World Bank tables should be viewed with suspicion as such data are based on extrapolation, rather than direct measurements. Directly measured estimates for Zambia show a rise in infant mortality from 176 to 190 per 1000 live births in the period between 1975 and 1992. As already indicated above the Zambia Demographic and Health Survey data conrms this nding. In Zimbabwe, infant and child mortality exhibited a downward trend throughout the early and mid-1980s. The infant mortality declined from between 120 and 150 per 1000 live births before 1980 to 61 by 1990, whereas the child mortality rate (children one to ve years of age) declined from around 40 to 22 per 1000 during the same period (Chabot et al., 1995). However, as UNICEF (1994; 1996) data indicate, evidence is accumulating that both indicators began to rise in the late 1980s and 1990s. In addition to economic decline, deteriorating health services and drought, the impact of HIV/AIDS is suspected to have contributed signicantly to the observed changes in infant, childhood and maternal mortality rates in countries such as Zimbabwe, Zambia, Botswana and Malawi. Blaming the World Bank and the IMF alone is misleading. Whilst economic problems in the region have had a great impact on health, and the World Bank has encouraged some countries to impose ocial programs of structural adjustment with very severe consequences, especially well-recorded in Zimbabwe, the World Bank has had no involvement in Botswana and very limited involvement in Angola and as well as none in South Africa and Namibia. This testies to the fact that there are other important inuences on poverty which have not been discussed in this paper due to limitations of space, notably war, servicing of debt, government corruption and world commodity prices. Thus it must be kept in mind that structural adjustment is but a part of a complex set of factors. Rising to the challenge The World Bank, a late comer in promoting better health care but an organization that has the means to make a dierence, has recently produced a number of encouraging policy documents. The Bank notes that

substantial health improvements in sub-Saharan Africa are not only imperative but also feasible (World Bank, 1994). The bank has set forth a new vision of health improvement that challenges countries and their external partners to rethink current health strategies. The discussion in this paper, although critical of the current health care conditions, would like to oer a complementary outlook to that espoused by the World Bank. The future is not yet lost and although the problems seem to be insurmountable it is our strong conviction that through commitment societies in southern Africa can turn the tide in their favor. Health care is a very high priority for both poor rural and urban communities, particularly the prevention of AIDS/HIV transmission. Policies which reduce barriers to access imposed by cost should be implemented. The training of health personnel should emphasize inter-personal skills and cultural sensitivity. The supply of drugs to rural clinics should be improved. One of the options to improve health care in rural areas is to implement a policy of decentralization in a more practical manner with each region getting its fair budgetary allocation. This was implemented in Zimbabwe during the early days of independence with remarkable results. There is need for urgent reform in the provision of health care facilities. As countries in sub-Saharan Africa liberalize their political systems with some success, it is time to turn attention to health. It should be recognized that health and development are intimately interconnected. The linkage of health, the environment and socioeconomic improvements requires intersectoral eorts (United Nations, 1992). Each country should marshal the limited resources and utilize expertise in education, housing, public works and community groups, including businesses, schools and universities and other religious, civic and cultural organizations. The gist of the approach is to enable local communities to ensure sustainable health care and development. Of greater signicance should be the inclusion of prevention programs rather than relying solely on remediation and treatment (United Nations, 1992). It is in this spirit that we suggest the following three target areas for immediate consideration in the health reform task. Primary health care for rural communities Governments and international organizations such as the World Bank and WHO should channel their energies to the provision of basic primary health care by providing the necessary specialized environmental health services, and coordinating the involvement of citizens, the health sector, the health-related sectors and relevant nonhealth sectors. Rural needs should be high on the agenda and the primary health care

980

E. Kalipeni / Social Science & Medicine 50 (2000) 965983

Fig. 4. Trends in human development index. Source: author, data from UNDP (1997).

approach should be developed and strengthened in an innovative manner. These should be community based, practical, socially and culturally acceptable, and appropriate to the needs of the community.

Eradication of communicable diseases The only way African countries are going to move through the various stages of the epidemiologic transition is through the eradication of communicable diseases on a sustainable basis. As noted earlier in this paper, advances in the development of vaccines and chemotherapeutic agents have brought many communicable diseases under control. But, as the discussion on the major causes of illness and death point out, many important communicable diseases such as cholera, diarrheal diseases, malaria, tuberculosis, measles, schistosomiasis and a host of other parasitic infections continue to pester the peoples of Africa. The eects of the AIDS epidemic have also been amply highlighted above. The impact of many of these diseases can be eased through serious environmental control measures, especially through the provision of safe water and sanitation. The environmental control measures, either as an integral part of the primary health care approach or undertaken outside the health sector, form an indispensable component of overall disease control strategies together with health and hygiene education (United Nations, 1992). In the case of AIDS, since a cure or vaccine appears to be a remote and unattainable possibility, governments should vigorously implement and enhance educational programs.

Protection of vulnerable groups In addition to meeting basic health needs, specic emphasis should be placed on protecting and educating vulnerable groups, particularly infants, children and women and the very poor. As noted earlier, in developing countries the health status of women and infants remains unacceptable and poverty, malnutrition and ill-health appear to be on the increase for these vulnerable groups. There is therefore an urgent need to strengthen basic health-care services for women and children in the context of primary health-care delivery, including prenatal care, breast-feeding, immunization and nutritional programs. Women's groups should be actively involved in decision-making at the national and community levels to identify health risks and incorporate health issues in national action programs on women and development. The education of girls should be promoted at all levels of the educational system.

E. Kalipeni / Social Science & Medicine 50 (2000) 965983

981

Concluding remarks This paper has attempted to highlight the major facets of health in southern Africa. The critical observations highlighted in preceding sections notwithstanding, data from southern Africa seems to indicate that southern Africa in general has made remarkable gains in reducing mortality levels across gender. Fig. 2 and 4 show the trends in the human development index (HDI) and other related indicators of health and wellbeing for countries in southern Africa. It is encouraging to see that even for a poor country like Malawi the trend in HDI is an increasing one over time. However, there exists marked intra-country and regional variations within the southern African subcontinent. For example, Angola, Mozambique, Zambia and Malawi stand out in having extremely high maternal, infant and childhood mortality rates. Although underfive mortality rates have declined over the past decade, they have done so very slowly from 258 deaths per 1000 live births during the 19781982 period to 234 deaths per 1000 live births for the 19881992 period. In other words 1 in 4 children do not live to see their fth birthday. On the optimistic side, countries such as Botswana and Zimbabwe have the lowest level of under-ve mortality in east and southern Africa as revealed by the DHS data. Namibia, Zimbabwe, Botswana and South Africa have under-ve mortality rates that range from a low of 40 for South Africa to a high of about 90 for Zimbabwe. Indeed gender related measures of development and empowerment seem to have improved dramatically in these countries. In short, the future of southern Africa in terms of gender dierentials in mortality, disease and health seems to be a mixed bag. Using the vulnerability perspective, the key to a more equitable future seems to lie squarely with increased levels of female education and autonomy. Due to inequitable access to educational facilities, it is no wonder that women in southern Africa occupy a disadvantaged position. Although women make up 70% of full-time small-holder farmers, they have little or no access to necessary resources to improve agricultural output (World Bank, 1992). Due to their inferior social status, they suer heavier seasonal weight losses than do men (24 kg versus 13 kg), suggesting that they receive more inadequate diets relative to food requirements than do men (World Bank, 1992). The educational discrimination against girls reported in research on education in this region inevitably results not only in lower employment and earning opportunities for women, but also subsequently aects the health and welfare of their children and families. As noted earlier the benets of educating women seem quite obvious. By providing quality education that does not discriminate by gender, men and women

would be able to compliment each other for the general good of the society in southern Africa. Among some of the visible benets directly related to female education are lower infant and maternal mortality rates, improved nutrition for children, and increase in economic productivity and more participation of women in the labor market. Indeed most governments in southern Africa are aware of the serious impact made upon family welfare of the disadvantaged and vulnerable position of women in society, and have made strong eorts to redress it, but the increasingly dicult economic circumstances could reverse any gains made in this respect.

References

African Development Bank, 1992. African Development Report 1992. Abidjan, Cote d'Ivoire: Development Research and Policy Department, African Development Bank. Aryeetey-Attoh, S., 1997. Geography and development in sub-Saharan Africa. In: Aryeetey-Attoh, S. (Ed.), Geography of Sub-Saharan Africa. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ, pp. 223261. Asthana, S., 1994. Economic crisis, adjustment and the impact on health. In: Philips, D.R., Verhasselt, Y. (Eds.), Health and Development. Routledge, London, pp. 5064. Becker, C.M., 1990. The demo-economic impact of the AIDS pandemic in sub-Saharan Africa. World Development 18, 15991619. Bloland, P.B., et al., 1995. Maternal HIV infection and infant mortality in Malawi: evidence for increased mortality due to placental malaria infection. AIDS 9 (7), 721727. Boerma, T., 1987. The magnitude of the maternal mortality problem in sub-Saharan Africa. Social Science & Medicine 24 (6), 551558. Boerma, T., 1994. Health transition in sub-Saharan Africa. Population and Development Review 20 (1), 206209. Bradley, D.J., 1991. Malaria. In: Feachem, R.G., Jamison, D.J. (Eds.), Disease and Mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa. Oxford University Press, New York. Campbell, C., 1997. Migrancy, masculine identities and AIDS: the psychosocial context of HIV transmission on the South African gold mines. Social Science and Medicine 45 (2), 273281. Carael, M., 1996. Women, AIDS and sexually transmitted diseases in sub-Saharan Africa: the impact of marriage change. In: Population and Women. United Nations, New York, pp. 125140. Chabot, J., et al., 1995. African Primary Health Care in Times of Economic Turbulence. Royal Tropical Institute, Amsterdam. Chisvo, M., Munro, L., 1994. A review of social dimensions of adjustment in Zimbabwe, 19901994. Unpublished paper. Costello, A., et al., 1994. Human Face or Human Fac ade? Adjustment and the Health of Mothers and Children. Centre for International Development, London.

982

E. Kalipeni / Social Science & Medicine 50 (2000) 965983 Kloos, H., 1994. The poorer Third World: health and health care in areas that have yet to experience substantial development. In: Philips, D.R., Verhasselt, Y. (Eds.), Health and Development. Routledge, London, pp. 199215. Kloos, H., Zein, Z.A. (Eds.), 1993. The Ecology of Health and Disease in Ethiopia. Westview Press, Boulder, Colorado. Kool, H.E., et al., 1990. HIV seropositivity and tuberculosis in a large general hospital in Malawi. Tropical and Geographical Medicine 42 (2), 128132. Kristensen, J.K., 1990. The prevalence of symptomatic sexually transmitted diseases and human immunodeciency virus infection in outpatients in Lilongwe, Malawi. Genitourinary Medicine 66, 244246. Lesetedi, L. et al., 1989. Botswana: Family Health Survey II: 1988. Gaborone: Central Statistics Oce and Institute of Resource Development/Macro Systems Inc., Columbia, MD. Lensink, R., 1996. Structural Adjustment in Sub-Saharan Africa. Longman Group UK Ltd, Harlow, Essex. Malawi Government, 1989. Health Information System: Reference Tables. Ministry of Health, Malawi Government, Lilongwe. McCracken, N., 1998. Letter from Embangweni. NYASANET Discussion Group, Thursday, 23 April 1998 (Posted letter from Dr Loomis stationed at Embangweni Hospital in Northern Malawi). McPake, B., 1993. User charges for health services in developing countries: a review of the economic literature. Social Science & Medicine 36 (11), 2530. Mead, S.M., et al., 1988. Medical Geography. Guilford Press, New York. Miotti, P., et al., 1992. A retrospective study of childhood mortality and spontaneous abortion in HIV-1 infected women in urban Malawi. International Journal of Epidemiology 21 (4), 792799. Moodley, V., Zama, B., 1997. The health status of women in a South African peri-urban settlement: the case of Amandawe, Durban, South Africa. In: Kalipeni, E., Thiuri, P. (Eds.), Issues and Perspectives on Health Care in Contemporary Sub-Saharan Africa. The Edwin Mellen Press, Lewiston, NY, pp. 179194. Namanja, G. B. et al., 1993. A Preliminary Report of Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STD) and Human Immuno-Deciency Virus (HIV) Seroprevalence Survey in Rural Ante-natal women in Malawi. Malawi National AIDS Control Programme, Lilongwe, and AIDSTECH, Family Health International. National Statistical Oce, 1991. Malawi Housing and Population Census, 1987. Government Printer, Zomba. National Statistical Oce, 1994. Malawi Demographic Health Survey, 1992. National Statistical Oce, Zomba, and Macro International Inc., Columbia, MD. Oppong, J., 1997. Medical geography of sub-Saharan Africa. In: Aryeetey-Attoh, S. (Ed.), Geography of Sub-Saharan Africa. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ, pp. 147 181. Oppong, J., 1998a. The medical consequences of social change: A political ecology of health care in contemporary Ghana. Paper presented at the Department of Geography

Cunnan, P., 1997. Family planning in an informal settlement: the case of Canaan, Durban, South Africa. In: Kalipeni, E., Thiuri, P. (Eds.), Issues and Perspectives on Health Care in Contemporary Sub-Saharan Africa. The Edwin Mellen Press, Lewiston, NY, pp. 165178. Department of National Health and Population Development, South Africa, 1991. Health Trends in South Africa. Department of National Health and Population Development, Pretoria, South Africa. Falola, T., 1992. The crisis of African health care services. In: Falola, T., Ityavyar, D. (Eds.), The Political Economy of Health in Africa. Ohio University Center for International Studies, Athens, OH. Feachem, R.G., Jamison, D.J., 1991. Disease and Mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa. Oxford University Press, New York. Gaise, K., et al., 1993. Zambia Demographic and Health Survey 1992. Lusaka: University of Zambia and Central Statistical Oce, and Macro International Inc., Columbia, MD. Gordon, A.A., 1996. Population growth and urbanization. In: Gordon, A.A., Gordon, D.L. (Eds.), Understanding Contemporary Africa. Lynne Rienner, Boulder, Colorado, pp. 167194. Gould, P., 1993. The Slow Plague: A Geography of the AIDS Pandemic. Blackwell, Oxford. Graham, W.J., 1991. Maternal mortality: levels, trends and data deciencies. In: Feachem, R.G., Jamison, D.T. (Eds.), Disease and Mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa. Oxford University Press, New York, pp. 101116. Homan, M., Pick, W.M., Cooper, D., Myers, J.E., 1997. Women's health status and use of health services in a rapidly growing peri-urban area of South Africa. Social Science and Medicine 45 (1), 149157. Ikinger, U., 1994. Schistosomiasis: New Aspects of an Old Disease. Ullstein Mosby, Berlin. Kalipeni, E., 1995. The AIDS pandemic in Malawi: a somber reection. 21st Century Afro Review 1 (2), 73110. Kalipeni, E., Craddock, S., 1998. Mapping the face of AIDS in southern and eastern Africa: patterns and prevention strategies. Paper presented at the Applied Geography Conference held in Louisville, KY, November 2429, 1998. Kalipeni, E., Kamlongera, C., 1996. The role of `theatre for development' in mobilizing rural communities for primary health care: the case of Liwonde PHC Unit in southern Malawi. Journal of Social Development in Africa 11 (1), 5378. Kalumba, K., 1990. Impact of structural adjustment programmes on household level food security and child nutrition: the Zambian experience. University of Zambia, Unpublished paper. Katjiuanjo, P. et al., 1993. Namibia Demographic and Health Survey 1992. Windhoek, Namibia: Ministry of Health and Social Services and Macro International Inc., Columbia, MD. King, M., King, E., 1992. The Story of Medicine and Disease in Malawi. Montfort Press, Blantyre. Klasen, S., 1996. Nutrition, health and mortality in subSaharan Africa: is there a gender bias? Journal of Development Studies 32 (6), 913924.

E. Kalipeni / Social Science & Medicine 50 (2000) 965983 Friday Colloquium, University of Illinois at UrbanaChampaign, January 30, 1998. Oppong, J., 1998b. A vulnerability interpretation of the geography of HIV/AIDS in Ghana, 19861995. The Professional Geographer 50 (4), 437448. Packard, R.M., Epstein, P., 1991. Epidemiologists, social scientists, and the structure of medical research on AIDS in Africa. Social Science & Medicine 33 (7), 771794. Paul, B.K., 1993. Maternal mortality in Africa: 19801987. Social Science & Medicine 37 (6), 745752. Population Reference Bureau, 1992. World Population Data Sheet. Population Reference Bureau, Washington, DC. Potts, D., 1995. Shall we go home? Increasing urban poverty in African cities and migration processes. The Geographical Journal 16, 245264. Reeve, P.A., 1989. HIV infection in patients admitted to a general hospital in Malawi. British Medical Journal 298, 15671568. Santow, G., 1996. Gender dierences in health risks and use of services. In: Population and Women. United Nations, New York, pp. 125140. Staneck, K.A., Way, P.O., 1996. The dynamic HIV/AIDS pandemic. In: Mann, J.M., Tarantola, J.M. (Eds.), AIDS in the World II: Global Dimensions, Social Roots and Responses. Oxford University Press, New York, pp. 41 56. Stock, R., 1995. Africa South of the Sahara: A Geographic Interpretation. The Guilford Press, New York. Streeand, P., et al., 1995. Implications of economic crisis and structural adjustment policies for PHC in the periphery. In: Chabot, J., et al. (Eds.), African Primary Health Care in Times of Economic Turbulence. Royal Tropical Institute, Amsterdam, pp. 1117. Svedberg, P., 1990. Undernutrition in sub-Saharan Africa: is there a gender bias? The Journal of Development Studies 26, 469486. Tevera, D.S., 1997. Structural adjustment and health care in Zimbabwe. In: Kalipeni, E., Thiuri, P. (Eds.), Issues and

983

Perspectives on Health Care in Contemporary SubSaharan Africa. The Edwin Mellen Press, Lewiston, NY, pp. 227242. UNAIDS, 1998. Epidemiological Fact Sheet on HIV/AIDS and Sexually Transmitted Diseases. World Health Organization, Geneva. UNICEF, 1994. State of the World's Children Report, 1994. Oxford University Press, New York. UNICEF, 1996. State of the World's Children Report, 1996. Oxford University Press, New York. United Nations, 1992. In Our Hands, Earth Summit: United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 112 June. United Nations, Department of Public Information, New York. UNDP, 1997P. Human Development Report. Oxford University Press, New York. United States Committee for Refugees, 1987. Uprooted Angolans: From Crisis to Catastrophe. American Council for Nationalities Services, Washington, DC. Wakin, D.J., 1998. AIDS wildre ravages southern Africa. The News Gazette Section B, Sunday October 25, 1998, p. B-4. Walker, J.C., 1994. Malaria and Other Parasites, 19002000. School of Microbiology and Immunology, University of New South Wales, Kensington, NSW. Watts, M., Bohle, H., 1993. The space of vulnerability: the causal structure of hunger and famine. Progress in Human Geography 17 (1), 4367. World Bank, 1992. Malawi Population Sector Study, Vol. I: Main Report. Population and Human Resources Division, Southern Africa Department, World Bank, Washington, DC. World Bank, 1994. Better Health in Africa: Experience and Lessons Learned. World Bank, Washington, DC. Zulu, E., 1996. Sociocultural factors aecting reproductive behavior in Malawi. Ph.D. dissertation, Population Studies Center, University of Pennsylvania.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)