Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Moore - Certainties Undone

Uploaded by

AnthriqueOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Moore - Certainties Undone

Uploaded by

AnthriqueCopyright:

Available Formats

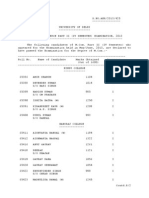

Certainties Undone: Fifty Turbulent Years of Legal Anthropology, 1949-1999 Author(s): Sally Falk Moore Reviewed work(s): Source:

The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, Vol. 7, No. 1 (Mar., 2001), pp. 95116 Published by: Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2660838 . Accessed: 24/01/2012 23:45

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute.

http://www.jstor.org

CERTAINTIES UNDONE: FIFTY TURBULENT YEARS OF LEGAL ANTHROPOLOGY, 1949-1999*

SALLY FALK MOORE

HarvardUniversity

This article reviews the broadening scope of anthropologicalstudies of law between 1949 and 1999, and considers how the political background of the period may be reflectedin anglophone academic perspectives. At the mid-century, the legal ideas and practicesof nonWesternpeoples, especiallytheirmodes of disputemanagement, were studiedin the context of colonial rule.Two major schools of thought emerged and endured. One regardedculturalconcepts as centralin the interpretation of law.The other was more concerned with the political and economic milieu, and with self-serving activity. Studies of law in nonWestern communitiescontinued, but from the 1960s and 1970s a new streamturned to issues of class and domination in Western legal institutions. An analyticadvance occurred when attention turnedto the factthatthe statewas not the only source of obligatory norms, but coexisted with many other siteswhere normswere generatedand social controlexerted. This heterogeneousphenomenon came to be called 'legal pluralism'. The work of the halfcenturyhas culminatedin broadlyconceived,politicallyengaged studiesthataddresshuman the requisitesof democracy, rights, and the obstacles to its realization.

What legal domains have anthropologists examined in the fifty years we are considering? How much have theirtopics changed? How much do the changesin topic reflect the shifting politicalbackgroundof the period?The big picture is simple enough. What was once a sub-fieldof anthropology largelyconcernedwith law in non-Western societyhas evolved to encompass a much largerlegal geography. now study Not only does legal anthropology industrial countries, but it has expandedfrom the local to nationaland transnational legal matters. Its scope includes international the legal undertreaties, pinningsof transnational commerce,the field of human rights, diasporasand and other situationsnot easily capturedin migrants, refugeesand prisoners, the earliercommunity-grounded conceptionof anthropology, thoughthe rich tradition of local studiescontinuesalong a separateand paralleltrack. in methodologyand theoThis expansionand change has involveda shift was the centre of the reticalemphasis.For a long while, dispute-processing with insight into local normsand practicesas an essential field, adjunct.Now, though looking at disputesremainsa favouredway of enteringa contested arena,the ultimateobjects of studyare immensefieldsof action not amenable and to directobservation. The natureof the statetoday, and the transnational supra-local economic and political fields that intersectwith states,are the

* Huxley Memorial Lecture,1999 Inst. (N.S.) 7, 95-116 J. Roy.anthrop.

C RoyalAnthropological Institute 2001.

96

SALLY FALK MOORE

intellectually captivating entitiesnow. Here, we will be looking at the issues legal anthropology addressedfifty yearsago and will traceits gradualprogress towards thesenew questions.Of necessity thiswill be a selectiveaccount,one politicalevents. which,whereit can,takesnote of the resonanceof background have been accompaChanges in the empiricalfocus of legal anthropology nied by disagreement about how to approachand answerthe question of how To formin a particular social setting. and why the legal acquires a particular have prevailed. simplify, one could say thatthreegeneralinterpretations

LAW AS CULTURE

particularly outside the West The first suggeststhat law is tradition-driven, but sometimeswithin it. Culture is all. However, culture is simply a label and practices. Those who treat denotingdurablecustoms, ideas,values,habits, part of thatpackage,and thatthe law as culturemean thatlaw is a particular has internalsystemic connections. combined totality on the constraining can be found in The stress power of 'the traditional' colonial conceptionsof the 'customary law' of subject peoples, and is deeply embedded in Durkheim's (1961) vision of what I mightcall 'the elementary It is also foundin Weber's(1978: 226-40) concepformsof social unanimity'. in some of Habermas's tion of 'traditional authority'. This view is reiterated A powerful (1979: 78-84, 157) evolutionary writingsabout law and society. versionof the culturalargument is foundin Geertz's(1983: 232-3) commenalso looms largein Rouland's (1988) textbookoverview. taryon law.Tradition with an apparently Cultural context once supplied some anthropologists innocent descriptiveexplanation of variationsin values and styles of life (see Hoebel 1954). But culturehas lost its political innocence.Today,when culturaldifference is offeredas a legitimationfor and explanation of legal cultural difference, context often comes up as an aspect of a consciously and it arises in the midstof a politicalstruggle, mobilized collectiveidentity and in relationto constitutions, collectiveinequalities, insidersand outsiders, other aspectsof nationaland ethnicpolitics.

LAW AS DOMINATION

in law can The second common explanationof legal formis thateverything be understoodto be a maskforelite interests, both in theWest and elsewhere. the generalinterest, but really serves Thus, law purports to be about furthering the cause of the powerful, and capitalism. (The conservagenerally capitalists tive counterpart, the law and economics argumentabout efficiency, has not enteredthe anthropological literature.) A versionof it is found is Marxisantin style. The 'elite interests' argument in Bourdieu (1987: 842), in the work of the CriticalLegal StudiesMovement (Fitzpatrick1987; Fitzpatrick & Hunt 1992; Kelman 1987), and elsewhere. For example, consider Snyder's(1981a: 76) comment concerning Senegal: law" historical the notion of"customary 'Produced in particular circumstances, was an ideology of colonial domination'.

SALLY FALK MOORE LAW AS PROBLEM-SOLVER

97

by some anthropologists (and many lawyers) The thirdexplanationoffered is a technical,functional one. Law is a rationalresponseto social problems. That is the explanationenshrinedin many appellate opinions as well as in conflictlaw is a problem-solving, sociological writings. In this explanation, in theWest arrivedat through rationalthought minimizing device,consciously Law at Harvard Ann Marie Slaughter, Professor of International and elsewhere. what is a commonplace Law School, was recently heard to expresssuccinctly in law schools,'I see law as a problem-solving tool' (pers.comm.). and appears is widelyused in the legal profession, This rationalist framework as one of the keys to modernityin Weber's sociology.Conceptions of law as essentiallyproblem-solvingwere also embedded in the essays of the in anthropology who was interested well-knownlegal realist, Karl Llewellyn, and wrote a book on the Cheyenne (Llewellyn& Hoebel 1941; for a brief however, Llewellyndid not make the critique, see Moore 1999). Importantly, in general) had a Weberian assumptionthatWesternsociety (and modernity In fact,he attributed thismode monopoly on sophisticated juridical thought. of thinking to the Cheyenne. as domination,as These three scholarlyexplanationsof law - as culture, - recurthroughout frequently the fifty yearswe will review, problem-solving mixed together. studiesand the general My review will emphasizefieldwork will be Anglophone contributions politicalbackgroundof legal anthropology. Reasons of but theyare by no means the whole story. given most attention, of French, Not onlymustI omitthe contribution space limitwhat I can discuss. also mustbe excluded.1 butmuchanglophonematerial Dutch,and otherwriters, Themes will be cited chronological, partly conceptual. My approachis partly as theyemergedhistorically, but subsequenttracesof the same ideas will someThat messes up the chronology, as they reappear. times be trackedforwards in the sub-discipline. but illuminates continuities

and rules reasonableness and therationales Gluckman ofjudges:reasoning,

in law and anthropology studiesat Gluckman was the dominantpersonality see Gulliver 1978; Werbner and beyond (for assessments, the half-century 1984), and he stood astridethe divide between the colonial and the postin Africain the colonial period,but went colonial in Africa.He did fieldwork decades work on a variety of topicswell into the first on publishing influential of independence. of the time,he was In the classicalmannerof Britishsocial anthropology the in discovering what had been the shape of pre-colonialsociety, interested 'true'Africa. Yet no one was more aware than Gluckman thatwhat actually him were Africansocietiesthathad experienceddecades of colosurrounded of economy and alterations nial rule,labour migration, Christianinfluence, the two Africasat once, the and more. He tried to understand organization, anthrohe was the first historical past and the living present.Furthermore, to study a colonial Africancourt in action, to listen pologist systematically as theyunfolded. to the storiesof complaintand the arguments carefully

98

SALLY FALK MOORE

law in Africahad generally Hitherto, been reportedas a set of customary rule-statements elicited from chiefs and other authorities. These so-called customary rules were then supposed to be used as guidelinesin the colonial courts (see e.g. Gluckman 1969). But customary law was, in fact,so altereda versionof indigenouspracticethatit mustbe recognizedas a compositecolonial construction. That began to be acknowledgedin Fallers's(1969) discussion of Soga law,and in Colson's (1971) writings and was made on land rights, unmistakably explicitby Snyder(1981a; 1981b), Chanock (1985 [1998]), and Moore (1986b). In Gluckman'stime,customary law was assumed to be largelyan expression of indigenous tradition, and when Gluckman listened to disputesand heard decisions,he focused on rules and reasoning.He tried to figureout what rule the judges were applying, what standardof reasonablebehaviour was being used.This was not alwayseasy or straightforward since the several judges in the highestLozi court oftendisagreedwith each other. Gluckman distinguished Lozi norms fromthe logical principlesused by judges to decide which norm to apply,and how and when to apply it. His argumentwas that, while Lozi norms were special to their society, Lozi juridical reasoningrelied on logical principlesfound in all systemsof law. Some subsequentcommentators saw thisas a falsifying Westernization of Lozi law. However, critics did not see that this universalist interpretation embodied a political position (Gluckman 1955: 362). Gluckman wanted to show that indigenous African legal systemsand practiceswere as rational in the Weberian sense as Western ones. Their premises were different because the social milieu was different, but the logic and the process of reasoningwere the same.To demonstrate thatAfricans were in everyway the intellectualequal of Europeans, he showed at tedious length (e.g. 1955: 279-80) what he saw as the comparabilities between Africanand Western Embedded in his gloss on Lozi ideas was a splendidmessage juridical thought. about racial equality. Ten years later,in a series of lectures,Gluckman (1965) commented on Barotse constitutional conceptions,ideas of property, notions of wrongdoing and liability, and conceptionsof contract, and debt.However,again obligation, he had a distinct preoccupation, comparison.He argued that certainBarotse of societies with a simple political economy: concepts were characteristic simple economy,low levels of technology, rudimentary political-socialorder. His comparative work orientation meritsmore explorationbut,untilrecently, of this sort had all but disappeared, partlybecause of serious methodological problems.2 However,beforethese problemswere recognized,Nader pursued the possibilitythat comparing the techniques of dispute management of different societies could lead to fruitful insights(see Nader 1969; Nader withTodd 1978). In time,legal anthropologists decided thattheycould finally not resolvethe issues of form, and contextthatthese sortsof comfunction, parisonsraised.However,such questionsare again being asked. What strikes one todayis the extentto which Gluckman (esp. 1955; 1965) was preoccupiedwith a racially of Africanlogic,and egalitarian interpretation an evolutionary of Africanpoliticaleconomy. These preoccupainterpretation tions displaythe reasoningof an anthropologist who was politicallyon the side of Africans, theirsocial systems and legal concepts yet who interpreted

SALLY FALK MOORE

99

as containing a substantial residueof an earlier, pre-capitalist economy.It seems not insignificant that,between the date of the first book and of the second, the colonial era had ended in mostAfricancountries. In his opinions,Gluckman had managed to identify simultaneously with Marx and Maine. The main point about my hastysummaryof a few of Gluckman'sargumentsabout law is thathe began a revolution in fieldmethodwith his attention to cases in court.Ever since,local dispute-watching has been the principal in legal anthropology form of social voyeurism (for a recentillustration, see Caplan 1995). What has been said here may suggestwhy Gluckmannot only of was the founderof the Manchesterdepartment but was also the initiator many durable controversies, which was verygood for academic business.

Lawv as an expression ofbasic, and often unique, cultural premises

One of the major criticisms immediately levelled against Gluckman's universalistnotions about legal logic was Bohannan's (1957) countercontentionthatin law,as in everything else,everycultureis unique, and that, for anthropology, its uniqueness is what is importantabout it. Bohannan contended that even translating the legal concepts of another society into English termswas a distortion. His is one of the more extremeversionsof the non-political'law as culture'argument. His contentionswere the object of a heated debate with Gluckman at a conference in the 1960s (see Bohannan in Nader 1969: 401-18). Many years later,a similarargumentwas offered by Geertz,in which he took'his distance'fromGluckman (Geertz 1983: 169). Geertz contendedthat - the Islamic,the Indic, the Malaysian- each threemajor culturaltraditions had different legal 'sensibilities'. He sought to demonstrate this by choosing two central concepts in each traditionand comparing them. He chose to all of these paired concepts as 'fact and law'. But of course,in each translate of these conceptswas not idenof the threetraditions the scope of reference tical.The resultwas a tourdeforce in part because Geertz used 'fact and law' as the translation for all three,and because he defined'fact' as 'what is true' and 'law' as about 'what is right'.That is not what the distinction between fact and law means in Anglo-Americanlaw, but Geertz's recastingof these termsinto philosophicaland moral ones is not accidental.He was not taking up conventional questionsof comparative law,he wanted to place these terms in a grandscheme of cultural thought. He argued(1983: 232), in a now muchand thatcomparithatlaw is 'a species of social imagination' repeatedphrase, sons should be drawn in those terms.He says (1983: 232) that'law is about law as an opportunity meaning not about machinery'.He saw comparative the analysisof cultural to shed lighton culturaldifference, and he identified difference as the centralpurpose of anthropologicalwork (1983: 233). So much for Gluckman'suniversals. The emphasisBohannan and Geertz put on the importanceof cultural but theirapproach difference preceded today'sfull-blown politicsof identity, resonateswith many currentformsof multiculturalism, as well as certainly withTaylor's(1992) ideas about the importanceof a politics of recognition. is a sectoral political cause in many parts of the Today,culturaldifference

100

SALLY FALK MOORE

world. No wonder that culture as the source of legal form remainsa live proposition(see Greenhouse& Kheshti 1998). It servesthose who have their own political reasons to emphasize collectiveboundaries,and to distinguish themselves fromothers. A lawyeranotherversionof the'law as culture'thesis. Rosen has generated he was at one time a student of Geertz,and has adopted much anthropologist, of the Geertzianpackage in his work. He has writtenon an Islamic village court in Morocco that deals largelywith familylaw, the court he studied He is concerned to show that, being restricted by statuteto such matters. the court does not make arbitrary despiteits lack of precedentsand records, decisions,that it does not dispense what Weber called 'kadi justice', even thoughthejudge has a greatdeal of discretion (Rosen 1980-1). Rosen (1989: 18) says:'theregularity lies ... in the fitbetween the decisionsof the Muslim judge and the culturalconcepts and social relationsto which theyare inextricably tied'. Anotherinstanceof 'legal form as culturalproduct' is French'ssketch of Tibetan law as it was in the period from1940 to 1959, a project of historical reconstruction. She calls her work a 'study in the cosmology of law in BuddhistTibet in the firsthalf of the twentiethcenturyas reconstructed', her effort as 'an exercisein historical and imaginaperspective characterizing tion' (1995: 17). She concludes that in dealing with dispute cases,Tibetan set of rules,but made juristsdid not make decisionsaccordingto a prescribed complex discretionary judgements.They approached each case as a unique combination of features, a perception which she attributesto Buddhist (1995: 343). philosophy, to a way of thinking about 'radical particularity' The link between a system of case-by-caserulingsand the BuddhistbackAfterall, materials. ground seems less certainwhen one looks at comparative in which hearingagencies there are many societies and institutional settings that are not Buddhistmake decisions case by case and emphasize situational such as the Islamic court describedby Rosen. Decentralizedinstiuniqueness, Are these the contutionalarrangements seem to be the crux of the matter. or social-structural history? sequence of religio-philosophical conceptions, That bringsus to questionsderivedfromtheWeberianconstruction of legal in the modernWest.To what extentare Western judges' decisions rationality in fact governed by mandatoryrules,and how much is leftto judicial discretion?Posner has provided some marvellously candid American answers. Posner is the eminentfounderof the law and economics movement, Professor of Law at the University of Chicago, and sometimecommentator on legal who now sitsas a judge on the Court ofAppeals of the Seventh anthropology, Circuit in the US. Though not all judges would admit,as Posner (1998: 235) does (and JusticeHolmes did), to using a 'puke' test of disgustas a way of deciding when to use discretionrather than to apply existing rules, his of his own reactionsand the importanceof judicial disacknowledgement in American law. cretionis neithernew nor revolutionary of law have However,with the exceptionof Rosen (1980-1) anthropologists usuallypaid littleattentionto judicial discretionin both Westernand nonWesternsystems. Of course,discretion can be difficult to detectif it is masked by an allusion to rules.Equally,acknowledgingthe importanceof discretion a purelyculture-driven undermines The problem-solving rationaleof analysis.

SALLY FALK MOORE

101

but invitesa question:in legal formis congruentwith the use of discretion, are decisionsmade?Where is the rule of law when judges can whose interest decide as theysee fit?Here we have an example of the way all threeof the modes of accountingfor legal form mentioned at the outset of this article ways in the project of explaining can become entwined in contradictory juridical thought.

and strategies interests Waysofusinglaw: litigant

became less and less likelyto see Since the 1960s and 1970s, anthropologists culturalpatterns driven by pre-existing behaviour as being overwhelmingly and social rules. Even in Bourdieu's Marxisantconception of social reproand duction,the idea of the 'habitus' (1977: 78) had to take improvisation into account. invention in choice interest The connection between the emerginganthropological and change and the socio-politicalbackgroundof the 1960s and 1970s is difwere promificultto provebut impossibleto ignore.Challenges to authority With in universities. repercussions of public life,with substantial nent features the end of colonial rule in the 1960s, the ex-colonized peoples were,at least complaintsabout Retrospective and legally, in charge of themselves. formally voiced. In the US theVietnamWar elicited the colonial period were actively The for the protesters. with legal repercussions enormous popular resistance, civil rights movement was launched. Legislative and social changes were its demanded and a lengthy ensued.The women's movementstarted struggle in a milieu in which a new technology of task of consciousness-raising contraception altered sexual behaviour, moral consciousness, and many in Europe. laws.There were analogous social hurricanes gender-oriented therewas not much In view of all of this contemporary political activity, Agency came into of law focused on conformity. place for an anthropology motives.Law was its own. Cases were heard and read in termsof litigants' of social order, but it was understoodto be usable in seen as a representation The strongand a greatvariety of ways by people actingin theirown interest. than the their interests more effectively powerfulcould, of course, further weak. some of thesechanges work thatintimated Early examplesof ethnographic in analyticattitudetowardsnormative justice appeared in Gulliver's(1963; he in colonialTanganyika, theArusha, anmong In his fieldwork 1969) writings. not by going to existobservedthattheyoftenmanaged theirlegal disputes, of 'informal', non-official, ing (colonial) Native Courts,but througha system of the contending parties Lineage representatives negotiated settlements. He concluded assembledand bargainedsolutionson behalfof the principals. were alwaysthe more politithatthe winnersof these negotiatedsettlements to referred The discourseinvolvedin thesenegotiations parties. callypowerful He outcome. norms not determine the but contended that did he norms, contrastedthis negotiation process with judicial decisions, in which he Thus he was still determined. assumed that the outcome was normatively not only thata normative system existed,but thatit was systematiassuming in formaltribunals. cally enforced

102

SALLY FALK MOORE

The analytic scenario changed even further in the direction of agency a few years later.Law began to be treatedas a set of ideas, materials, and institutions thatwere being used as a resourceby people pursuingtheirown interests. For example, Collier's ethnographicwork among Maya-speaking Mexicans treated Zinacanteco legal categoriesand concepts'as a set of acceptable rationalizations forjustifying behavior' (Collier 1973: 13). Her central objectivewas to identify the Zinacantecos'way of conceivingthe world and in the lightof theseideas.However, theirhandlingof transactions and disputes Collier also made it clear thatthe Zinacanteco world was farfromcompletely of Mexican stateinstiautonomous,farfromimperviousto the interventions tutions.Collier showed that the Zinacanteco legal systemwas neitherstatic nor insulatedfromthe outside world. The early Gulliver challenge to Gluckman about whether power or norms determinedthe outcome of disputesremainedlivelyin England for a time.A conference of theAssociationof Social Anthropologists even carried this as its theme (Hamnett 1977). Definitivelyputting the lid on that ASA discussion,and supportingtheir argumentwith convincing empirical materials, Comaroffand Roberts (1981) produced a well-knownand widely rules did not read book that made the point that,even in judicial tribunals, always rule. Using case material collected among the Tswana of southern Africa,they showed that many types of dispute-processing could exist in Rules and the social relationsof litigants, as well as their the same system. interests, appeared within the same universeof litigation. The cases demonstratedthatTswana often took the opportunityto use arenas of litigation to renegotiatepersonal standing,to obtain recognitionof social relations that were being contested(1981: 115). This kind of confrontation occurred about norms:the languagein which the arguments as if it were an argument were presented was'culturally inscribedand normatively encoded' (1981: 201). They speak of 'dualism in the Tswana conception of theirworld,according to which social life is described as rule-governedyet highly negotiable, normatively regulatedyet pragmatically individualistic' (1981: 215). 'Disputes range between what are ostensibly norm-governed "legal" cases and others that appear to be interest-motivated ... The point, "political" confrontations however, is not simplythatthese different modes co-exist in one context... but that they are systematically related... transformations of a single logic' (1981: 244). Is thisaccommodationof contradictory ideas specialto theTswana,or more general?I would argue that this situationis commonplace. In keeping with thisview,on a numberof occasions in the 1970s I argued thatthe sociology of causalitywas ill served by a conformity-deviance model of the place of rules of law in societies,as if therewere a single set of rules,clearlydefined, or ambiguities and withoutcontradictions totally discrete, (Moore 1970; 1973; is a peculiar mix of action congruent 1975a; 1975b; 1978). 'The social reality with rules (and theremay be numerousconflicting or competingrule-orders) and otheraction thatis choice-making, discretionary, manipulative' (1978: 3). What also matters is that the choices and manipulations are not only made in disputesituations, who by the litigants theyare also made by the authorities decide what the outcome shall be, and who make reference to norms and normativeideologies in other contexts.

SALLY FALK MOORE

103

oftencharacAllusionsto rules or ideologies with normativeimplications The place in and out of disputecontexts. terize the behaviourof authorities by authoritiesand leaders is an issue as important of moralizingstatements between legal rules and behaviour as is to the analysisof the relationship and of authority The organization manipulations. of litigant the understanding of normativeideas is a major piece of the its relationto the representation of law.By (or non-implementation) and implementation presentation, framing, have gained some access to the statusof anthropologists focusingon dispute, and others normativebody of ideas, but what the authorities thatputatively actuallydo with them is somethingelse again.

in theinterpretation issuesofclassand domination authority: Questioning of law

it is oftenassumed Given theirlack of doctrinaland technicallegal expertise, societiesare best offobserving'inforindustrial studying thatanthropologists mal' legal processesanalogous to those found in small-scalevillage communisuch as small claims ties: negotiation and mediation,informalinstitutions law,and the family generatedneighbourhoodarrangements, courts,internally have done successfulfieldworkand case like. A number of anthropologists of social They contributeto our understanding analysisin just such settings. and culturalissues other than those which would turn up in more formal settings: popular attitudestowards litigationand towardslegal institutions, the actual practices conceptionsof law as part of the cultureof community, in interaction of officials with lay people, and the like (Abel 1982; Conley & & Engel 1994; Merry O'Barr 1990; Greenhouse1986; Greenhouse,Yngvesson 1990;Yngvesson 1993;Yngvesson & Hennessey 1974). However, in the 1970s a curious test of the anthropologicaltaste for embraced by was officially appeared when informality informalinstitutions When the courts added AlternativeDispute the American judicial system. were not anthropologists Resolution (ADR) to options open to litigants, pleased.ADR was publicized as a responseto the needs of the poor and of those who had minor claims that would otherwisehave gone unheeded.3 because theircourt calenHowever,the judiciary embraced the programme thattheywanted some judges remarked darswere overloaded.Less felicitously, to get 'garbage cases' out of theircourts (Nader 1992: 468). minded (see Nader 1999), argued public-interest Nader, being passionately that,in fact,the courts themselvesshould be made more accessible to the poor. She (1980: 101) assertedthat the legitimacyof a legal systemin a democracydepends on providingaccess to the courts for all. This resonated in two ruralZapotec villagesin with her earlierwork on disputesettlement Mexico, work which began in the 1950s (see Nader 1990). When Nader first startedthis project therewere no lawyersin these villages,and the position of judge rotatedamong the senior men, each one servinga fixedterm.The to work out compromise as mediators, saw themselves trying judges evidently her experience in Nader described in conflict. between solutions persons Mexico when she lectured at American law schools, and she reproached her audiences for not trying to provide less expensive, more accessible

104

SALLY FALK MOORE

compromisesolutionsto the everyday problemsthat were commonplace in Fromthe start, work to comment she used her ethnographic the United States. of American society. on what she saw as the shortcomings But when many jurisdictions actuallyestablished ADR, Nader's reactionwas negative.She contended that the question was what was just and what was unjust under the rule of law, not whetherpeople could be forcedto comNader (1993: as ifit were some kind of therapy. promisein mediatory settings 4) asked what this coercive 'harmonyideology' signifiedin relationto the themes in Americanlife.Here we have one of the threerecurrent inequalities of the law as serving the representation about legal form mentioned earlier, when it should be solving problemsfor rich and poor alike. elite interests Nader (1992: 468) is clear about what she sees as the connection with the politics of the period. 'Tradingjustice for harmonyis one of the unrecogmovements nized fall-outs of the 1960s ... In an effort to quell the rights (civil environmental and to cool out rights, women'srights, consumerrights, rights) theVietnam protestors, harmonybecame a virtueextolled over complaining or disputing or conflict'. Other critics of the ADR movement also argued that such mediatory measuresreduced social conflictthat mightreformsociety (e.g. Abel 1982). That seems to me a big and not altogether warranted interpretative leap, but for some it seemed a certainty. Thus, Merry (1990: 9) also speaks of mediation as 'a processof cultural dominationexercisedby the law overpeople who bring theirpersonalproblemsto the lower courts'.But in her fieldwork, the many individualtroublesbroughtto mediationseem to be only tangentially connected with social class, and indeed seem to be the sort of personal grievances between individualswho know each other well which might husbandsand wives,parents appear in any class,disputesbetween neighbours, and children. to social class is the fact that Merry'speople What is plainlyattributable findthemselves in a public mediationprocess, rather thanusingprivate lawyers to negotiate for them. In mediatorysettingsthey subject themselvesto a considerabledose of patronizing But the question advice,oftenpsychological. that remainsis whether what transpires has much to do with a 'harmony in check. ideology' thatkeeps major social confrontations Nader also applies her 'harmonyideology' thesisto her historyof disputing in a Mexican-Zapotec mountainvillage.Her current vision of the village's history is that the people presented themselvesas resolving all disputes as part of a politicalstrategy to keep colonial authorities from harmoniously meddlingin village affairs (1990: 310). She says that harmonyideology was the price of village'autonomyand self-determination' (1990: 321). The work of Nader, Merry, how some people drew an and Abel illustrates analogy between the situationof colonial people and the poor in industrial countries. Obliquely drawninto the same model in otherworksis the predicament of women in asymmetrically gendered situations, oftenin ex-colonial What motivates is the idea thatlaw should mean equal these writers settings. foreveryone. and treatment it oftendoes not,eitherbecause rights Obviously, of lack of access, or other obstacles(Griffiths judicial bias, 1997; Hirsch 1998). for some the theme of domination and resistance Thus, anthropologists as the of their of theirwriting and emerges principalaspect interpretation law,

SALLY FALK MOORE

105

impliesthatlatent, unrealizedmajor social protests and revolts arejust waiting to happen.But thatis probablya greatexaggeration, and has littleto do with domesticdisputes, between neighbours, fights landlord-tenant arguments, and consumer complaints. There may well be a lot of resentment embedded in these disputes, but does it represent potentialmobilizationfor social reform? It seems plain that an unnuanced domination-resistance model is too simple a framework of sites of control and the sources of to capture the diversity social movements. Hirsch (1994; 1998) and Griffiths (1997), concerned with the complexitiesrevealedby detailed studies,and show the gender,illustrate considerabledifference between using the idea of resistance on the one hand and, on the other, imputing resistancein more generalized critiques of domination. The complexities involved in analysinghow law, economy,and sociopolitical change are interconnected are particularly evident in longitudinal, A few anthropological historical studies. workshave combined detailedlegalhistorical materialwith ethnographic fieldwork. In the 1980s, Snyder(1981b) wrote a Marxistaccount of capitalismand legal change among the Diola of Senegal, and Gordon and Meggitt (1985) traced changes in government in New Guinea fromcolonial times. In the first authority wave of ethnographic-historical studiesof law, I wrote an ethnography-cum-history of the people of Kilimanjarofrom 1880 to 1980 (Moore 1986b). This interweaves the storyof the lives and legal disputesof livingindividuals(and thatof their lineage ancestors) who gave accountsof theirown experienceswith the documented record of economic, demographic, and institutional change on the large scale. A few years afterNader published her historicalZapotec study, LazarusBlack (1994) followed the uses of the courts in Antigua and Barbuda that bore on slavery. She shows how the law was used to restrict slavesand protect but also how slaves were, at times,able to use the courts for slave-owners, their own advantage. Most recently, the Comaroffis have included some remarksabout law in their historyof missionary and colonial activitiesin Their generalapproachto history is encapsulated southernand central Africa. in the idea that'the European colonizationof Africawas oftenless a directly coercive conquest than a persuasiveattemptto colonize consciousness,to remakepeople by redefining the taken-for-granted surfaces of theireveryday worlds' (Comaroff& Comaroff1991: 313). Some ideas basic to English law in with the indigenous life world and become instruments are inconsistent the colonization of consciousness. They remarkon the way ideas of private and possessiveindividualism, lawfulwedlock, and other legal conproperty ceptions,fitinto the project of revisingthe way Africans thoughtabout the world theylived in (Comaroff & Comaroff1997: 366-404; see also Comaroff 1995). of each of the colonial experiencesstudiedin the The historical particulars Each area was involvedin (or made works mentionedabove differed greatly. in the a distinctive world peripheral by) economy way,colonized in a differwhich shifted ent way.Each had a distinctive social and culturalformation, over time,both before and aftercolonization.That the common European backgroundof the colonizersgave the colonized a stock of similarlegal ideas is no surprise. is the remarkable What is striking variationin the way these

106

SALLY FALK MOORE

ideas were receivedand used by the dominatedpopulations(fora reconsidissues,see Moore 1989a; Roberts & Mann eration of some legal-historical 1991; Starr& Collier 1989).

themoving partsof thestate disassembling Legalpluralism:

revised has been more thanslightly The concept of the stateas a unifiedentity Cultural pluralismand political divisionshave long in the past half-century. of manypolities(Furnivall1948; been recognizedas basic and durablefeatures have distinctcollectivities dealing with culturally Smith 1965); governments in legal terms (Hooker 1975). In the often acknowledged such differences 1960s, the early period of independence,the legacy of colonial pluralism debate (e.g. Kuper & Smith 1969; Moore 1989b).4 loomed largein intellectual about whetherthe newly independentstatesof contention There was much given thattheywere interAfricawould succeed in becoming unifiednations, that nally divided and had a historyof being ruled by colonial governments oftenreinforced the boundariesbetween ethnic groups. and constitutional, political, posed profound That ethnicand racialpluralism otherlegal issueswas evidentnot onlyin Africabut elsewhere(Kuper & Smith (1984) 1969: 438-40). These issuesspelled troubleahead, and Maybury-Lewis addressedthis by askingwhat mightbe the politicalconsequences of official Recent eventsin the Balkans provide a gloomy policies based on ethnicity5 the term 'pluralism'is repeatedly answer.In this kind of political literature of institutionally used to referto societies which incorporate a diversity It is, for example,used in thatsense by Tambiah (1996) collectivities. distinct in his book on ethnicviolence in Asia. these days,'pluralism',or more precisely'legal But in legal anthropology new use different sense. One relatively is oftenused in an entirely pluralism', the 'legal centralism', (1986: 3), who attacks dates froman articleby Griffiths orderingof and unifiedhierarchical systematic idea thatlaw is 'an exclusive, fromthe state.One is hard put to imagine emanating normative propositions' what social scientistsupportssuch a contentiontoday,but it makes a nice asserts thatthe legal reality anyforhis further Griffiths argument. springboard where is a collage of obligatorypracticesand norms emanatingboth from sourcesalike.He (1986: 39) says'that... and non-governmental governmental package,of whatall social controlis more or less legal'.The whole normative ever provenance, is what he calls 'legal pluralism'. article was published,a symposiumwas held on ShortlyafterGriffiths's paper was in industrialized societies',in 1988, and Griffiths's 'Legal pluralism reviewedand publicized by Merry (1988: 879) in a much-citedarticlesum(see Greenhouse & Strijbosch 1993; Teubner 1992). marizingthe literature some writersnow take legal pluralismto referto the Following Griffiths, norms of social whole aggregate of governmentaland non-governmental their source. drawn as to without distinctions any control, has to be disaggregated. However, for many purposes this agglomeration mustbe made thatidenFor reasonsof both analysisand policy,distinctions tifythe provenanceof rules and controls (Moore 1973; 1978; 1998; 1999; fromotherrule2000).To deny thatthe statecan and should be distinguished

SALLY FALK MOORE

107

purposesis to turnaway fromthe obvious. formanypractical makingentities useful And if one wantsto initiateor trackchange,it is not only analytically sitesfromwhich norms to emphasize the particular but a practicalnecessity to is not necessarily To make such distinctions rules emanate. and mandatory view.6 adopt a 'legal centralist' is not just legal pluralism It is clear thatmuch of the debate thatsurrounds an argumentabout words,but is oftena debate about the state of the state The discourseon thistopic one thatasks where power actuallyresides. today, of the statethrough transformations about current getsmixed with arguments throughtransnational the empowermentof sub-nationalcollective entities, phenomena,and 'globalism'.Today,'pluralism'can referto: (1) the way the itself state acknowledges diverse social fields within society and represents in relationto them; (2) the internaldiverideologicallyand organizationally subthe multipledirectionsin which its official sityof state administration, (3) the waysin which the state and compete forlegal authority; partsstruggle itselfcompetes with other statesin largerarenas (the EU, for one instance), and with the world beyond that;(4) the way in which the stateis interdigisemi-autonomous and externally)with non-governmental, tated (internally normsto which social fieldswhich generatetheirown (non-legal) obligatory they can induce or coerce compliance (see note 6); (5) the ways in which law may depend on the collaborationof non-statesocial fieldsforits implementation; and so on. case for the appropriWilson (2000) has made a persuasiveethnographic in his discussionof human view of legal pluralism atenessof such an intricate of diverseideas of justice, rightsin South Africa.He shows the simultaneity throughwhich these contradicas well as the proceduresand performances sources,are given practicalform,from tory ideas, emanatingfromdifferent and reconciliationto public beatings.His is a subtle,complex, historically implied when one talks grounded,picture of the struggles ethnographically about legal pluralism.

works to democracy: three recent very Askingaboutobstacles

in the legal to engage with presently are using theirinterest Anthropologists than ever.And no wonder: them more directly addressing politicalquestions, the 1980s and 1990s have seen as much political upheaval as the previous We live now in a post-socialist, post-Cold War,post-apartheid twentyyears. and replaced.Queshave been overturned period in which manygovernments tions are raised about the new regimes and whether they are or will be 'democracies',and about what 'democracy'means.Building new regimesand old ones occur in many partsof the world.The legal dimensions reforming attennew kindsof anthropological of theseprocessesare beginningto attract a is not of national the construction tion. However, processthat governments enter matters. Global concerns inevitably can be divorcedfromtransnational the discussion. The academic debate that surroundsthese issues is uneasy,but it has This can be illustrated by begun to considerlarge-scalecontextin novel ways. threestrikingly different anthropological approachesto the legal domain,all

108

SALLY FALK MOORE

published in the past two years and all concerned with civil rights.I shall describe the books verybriefly to give a sense of the way the field of legal anthropology is now givingvoice to new formsof directpoliticalcommenall threehave to do with the idea of democracyand what tary. Theoretically, to make of it. All three analyselegal eventsframedin the context of mass in a world conceived globally. communication law. Coombe is I begin with Coombe (1998), concerned with trademark and in her hands'trademarks, protected both a lawyerand an anthropologist, authority' (1998: 286) indiciaof celebrity personas, and marksof governmental and oftenfunny become the occasion fora remarkably interesting set of essays on emblemsin the mass media and the culturallife of intellectual properties. The insigniaof Coca Cola, the image of MarilynMonroe, and certainbadges officeare recognizableto everyone, but theycannot be used of governmental freely by all. Coombe argues that our environment is filled with these manufactured The productionof demand throughthe advertising of commodities symbols. and the publicizingof celebritiesfillsour environment and stuffs our consciousness.She says that'such images so pervasively permeate all dimensions of the "cultures"in which most of our daily lives that they are constitutive They furnish people in Westernsocieties now live' (1998: 52). She is right. of images and our native thoughtand our naturalworld.And this inventory names is being extended throughmass communicationto the rest of the world.Batman lives in NewYork, Hong Kong, and Dakar. Coombe's heart is obviously with those who use these symbolsillegally to satirize them (1998: 271). She contends that,because the symbols are formsare the or "recoding"cultural ubiquitous,the 'practicesof appropriation she is askingus essence of popular culture'(1998: 57, see also 285). In effect, to our commercially constructed to pay more attention symbolicenvironment and to who owns it and controlsits content and deployment.Expressive be unfettered, to permit she argues(1998: 186, 194), should generally activity, I question whetherrestrictions on of a dialogic democracy. the construction interthe freedomto copy MacDonald's Golden Arches trademark directly fereswith democratic dialogue, but that does not detractfrom Coombe's and into our trademark-infested symbolicenvironment many other insights communicationis not altogether its commercialcontrol.Plainly, free,when our symbolicvocabularyis supplied under these conditions. The second book is a collectionof essaysedited byWilson,which presents some of extremepersecution. a numberof studiesof human rights situations, But the orientationof the book is not only on what happened,but also on have been reported and discussed.Wilson on the way thesesituations discourse, (1997: 13) describesthe collection of essaysas 'an explorationof how rightsand materialisedin a based normativediscourses are produced, translated 'the tensionbetween global and varietyof contexts'.Each chapterconfronts the contribulocal formulations of human rights'(1997: 23). What interests tors is the way that strugglesin a local field of action are 'structured by transnational discoursesand practices'(1997: 24). These are, of course, very as are the situations described. diverse, Fieldworkconcerned with human rights is by definition carriedout in an arena of conflicting oftenat terriblemomentsof reportsand representations,

SALLY FALK MOORE

109

have to say about crisis. What can anthropology add to what otherdisciplines what anthropologists can such matters? Wilson's collection candidlyaddresses Contributorswillingly and cannot do, and that is one of its distinctions. competence.The problematic that acknowledgethe limitsof anthropological contributors addresshas obviouslybroadenedbeyondthe accumulatedknowledge of one profession, beyond one locale, and oftenbeyond one momentin law,with transnatime.Now anthropologists are tanglingwith international with the aftermath of nationalpoliticalpersecution, tional political relations, and with the way eventsin these arenasare being reported. The thirdbook, by Borneman (1997), embodies just such material.He describesthe public demands forjustice thatwere heard afterthe fall of the BerlinWall and the beginningof German unification. East Germanswho had in other ways under the socialistgovernment been denounced or suffered were demandingthatwrongsbe set right, thatsome meansbe foundto restore their lost dignity, There also were demands that names, or reputations. members of the East German elite be prosecuted and that propertybe formswere inventedto satisfy returnedor redistributed. Various institutional in some of them. these demands,and Borneman did fieldwork lawyerwho was an Borneman describesthe prosecutionof an important intermediary between East and West Germanyin the days of theWall,a case that raises the issue of the retrospective criminalization of acts which were legitimate when carriedout. He also tellsus about the hearingsset up within the radio and television to deal with social injuriesexperiencedthere. industry Borneman (1997: 99) argues that all of these proceedingswere (and are,for to establish the stateas a moral agent. The new state theyare not over) efforts tried to dissociateitselffromthe crimes of the past. For the state,recognizand a symbolicact of ritual ing injusticeswas both a practicalact of redress of offiBorneman affirms the importance Withinthisframework, purification. He argues that such recognitionpoints to a cial recognitionof suffering. 'into the of the natureof the citizen.Suffering is reincorporated reassessment of the nationalsubject' (1997: 134). identity He ends with summariesof data fromother East and Central European fouryearsafter At its broadesthis argucountriesin the first regimechanges. the book is thatfailure to engage in retributive justice leads ment throughout that therecan be no violence and, most importantly, to cycles of retributive law realizedthrough democracywithoutpoliticaland personalaccountability (1997: 3, 145, 165). All narrower All threeof these books departfroman earlier, anthropology. in and with transnawith law deal with contestedpoliticalprinciples, action, All are All take explicitpositionson the issues theyaddress. tional questions. with native but not with customs, tragic possibilities concerned, charming scene. glimpsedin the fieldwork

Conclusion

It is obvious that legal anthropologyhas been saturated with political the anthropological project messagesin the past fifty years.At mid-century, of the 'indigenous' legal practices of was to elaborate on the rationality

110

SALLY FALK MOORE

non-Westernpeoples, most of them under colonial domination.Law was addressedas a technique for managing disputes,as a local problem-solving method,its stylethe product of cultureand history. For obvious reasons,at the time therewas littledirectcritique of colonial rule. In the post-colonial world, the practices of colonial governments were attackedas never before.Attentionalso turned to Westernlegal institutions and governments, and law both in formercolonies and in theWest was seen distortions as a rule imposed by some on others, oftenwith systematic (Abel 1982; Burman & Harrell-Bond 1979; Chanock 1985 [1998]; Fallers 1969; Galanter1989; Moore 1986a; 1986b; Nader 1980). For some, dominationand resistance were the analyticpreoccupation. But at the same time,the cultureminded continued with their own form of legal analysis, attendingto the and theirsituavarietyof ways thatpeople conceived the world,themselves, and continued to that these cultural tions, presume conceptionswere causative. In the United States this was the period of the Vietnam War, with its of the civil rights the women's movement, accompanying protests, movement, and overshadowing that there should all, the Cold War. It is not surprising have been an accompanyinganthropological And critique of legal authority. on the theoretical of agency to the anthropologiplane,with the attribution cal subject,the importanceof action and choice modifiedthe earlierdominant vision of normativerules as the centralconcern of culturaland legal analysis. A broadened definition of reglementary controlemerged.Control came to be seen as exercisedin and by multiplesocial fields. The perceptionthatmany redefined sitesof controlexistedsimultaneously the stateas only one among many sources of mandatory obligation. Debating the concept of semiautonomous social fieldsand the idea of legal pluralism, legal anthropology redefined its object and itself. Could one identify the newest concern in legal anthropology today?As I see it exemplified in the three studiesI have just described,that concern is with a verymuch wider vision of the politicalmilieu in which law is imbricated.They inspectthe legal data forinputsand eventsin the global political turbulenceof the day.Whether it is the law-relatedcontrol of intellectual of human rights, of personsfor property, the definition or the accountability it is evident that nothingis merelylocal in its forthe policies of regimes, mation or in its repercussions. As I see it,theircommentary, directand indirect, on the possibility of realizing democracyis profoundly important and innovative. They are using their fieldwork to show the negativepoliticalimplications of actionstheyhave witnessed. They are saying that if what they have described continues,open will be troddenunderfoot, democraticdiscourseis unachievable, human rights well of violence themselves. cycles may repeat This approach is importantbecause it involves a newly selective use of fieldwork data to comment on the large culturaland politicalentitieswhich the fieldwork the mixed and miscellaneous describes.Within aggregations that are the stateand thatcompose the global scene,thisapproachfocuseson the elementsthatare willed legal creations. It is the potentialfuture of thatintendimensionthatthese threeworks address.7 tionallyconstructed They involve small-scale fieldwork, but comment on large-scale issues. The two levels

SALLY FALK MOORE

111

are harnessedwhen the writerasks whether the field work data show that and thereare major obstaclesthatstandin the way of realizingthe freedoms accountabilities thatare part of the ideal of a liberaldemocracy. These works ask, 'What kind of a world is it in which these particular They use fieldwork on eventsare actuallyhappening?Is democracypossible?' legal issues to identify legal and non-legal practicesthatstand in the way.In inferthe process they redefinethe scope and directionof anthropological could accommodatewhat they ence.They ask what kind of a politicaltotality describe.8Coombe, Wilson, and Borneman directlyconfrontthe legal production of political consequences.That is the way they have framedtheir analyses. They are not just talkingabout what is going on. They also are talking about what could go on. They are willing to consider the democraticideal, while pointingout how farshortpeople are of realizingit.They are treating theirown criticalcommentary as a formof social action.They are moved to of many laws and legal institutions. But they question the damaging effects are also mindful thatin some countriesand in some international institutions, but law is being used forreconstructive purposes.It can make social disasters, in some situations it can help to preventand repairthem. are moved to ask under what conditionslegal instiWhen anthropologists tutionscan contribute to democraticpractice, theyare inadvertently showing for intentionalaction. some small signs of optimismabout the possibilities that even a habituallysceptical professioncan Such enquiries demonstrate At the veryleast,situations acknowledge thatperhapsthingscould be better. could be betterunderstood. To thisend, anthropology has expanded the scope of its own scholarlyanalysisby contextualizing legal field materialsmore and more deeply.It has alwaysknown thatlaw is a major politiextensively and it has alwayshad somethingto say about the way law has cal instrument, it has aspired to alter been used. But in recent decades it has gone further, the way law is conceived.

NOTES of as the Huxley Memorial Lectureat the University presented This was originally anniversary thefiftieth celebrating in 1999 at theopening session of a symposium Manchester of Manchester's department of anthropology. of thefounding but whichare so important thatI do not have space to discuss, 'There are two domains the otheris the here.One is the studyof property, thattheymustat leastbe mentioned

of law. sociohlnguistics

not dealingwith the idea of property, Property.There is a vastbody of rich material It toucheson everything fromkinship to inheritance, amenableto briefcharacterization. of land to economic theredistribution 'ownership' of land,from from to individual collective to redistribute land;Peters attempts and beyond(see Low 1996 on worldwide development, 1994 on dividing thecommons). systems of land tenurehave oftenreceived In the contextof economic development, in particular with thiswork. are associated from Four institutions attention anthropologists. by M. Alliotand E. Le Roy, juridiquein Paris,directed d'anthropologie The Laboratoire foundedby R. of ParisX-Nanterre, at the University and the CentreDroit et Cultures The LandTenureCenterat the systems. on African property haveproduced studies Verdier, studyof land tenuresystems of Wisconsin is concernedwith the comparative University F von in the Netherlands, At theAgricultural University ofWageningen all overthe world.

112

SALLY FALK MOORE

on property in Indonesia. withK. von Benda Beckmann, Benda Beckmann focuses Together he has produced an important seriesof publications (1979; 1985; 1994; & with H. Spiertz 1996). recent Sociolinguistic approaches to law. A number of illuminating, relatively use sociolinguistic to analyse publications techniques legal materials (e.g. Conley & O'Barr to the 1990; 1998;Mertz1994;O'Barr 1982).The analysis of theform of legaltexts, attention of speechas texthavebeen sigverbal disciplines usedin legalproceedings, and thetreatment additions to thetool kitof legalanthropology. nificant methodological A particularly clearand subtle recent workthatshowswhatcan be done is Hirsch(1998). in East of gendered She usesdetailed to showtheeffect linguistic analysis speechin litigation to makeclaims, thelanguage usedbywomento describe their Africa. She showsthat situation, at once describes their and how they and to carry on legaldisputes, and illustrates predicament feelaboutit. After Attention to thelinguistic dimension of thelegalwill doubtless grow. all,it is thelaw thatgivesmany statements and written actstheir ultimate authoritative performative efficacy. to the abandonment of comparison. For example, Newman 2There are a few exceptions withMurdock-like For (1983) usesa Marxisant approach combined quantitative comparisons. new kinds of comparison, see Greenhouse (1996) and Bowen and Petersen (1999).Of course, law continues as a specialty within thelegalprofession and involves some of the comparative to what is being comparedthat anthropologists have same theoretical problems relating addressed (see Moore 1986b;Riles 1999). the general 3In the same period,a majorinternational was undertaken to inspect survey problem ofaccessto legalinstitutions (Cappelletti & Garth 1978-9;Cappelletti & Talon 1973). in manycountries. Alternatives to thecourts weresought non-ethnic withinanthropology sites of the multiple 4There was an earlier, conception of legallevels. wherelaw could be generated, Pospisil's theory He postulated thatevery social had itsown internal to groups suchas families, and comsub-group 'law',and he alluded clans, munities. He (1971: 273) said:'We haveto ask whether a givensociety has onlyone consistentlegalsystem ... or whether there are several suchsystems'. of pluralism as a process; Greenhouse 'See Moore (1989b) on the production (1996) on and ethnography. democracy 6See Moore (1973) on semi-autonomous socialfields, a paperfrom whichGriffiths drew and whichhe citeswithapproval. inspiration thisissuein various 7I havetriedto address waysin myown recent writings (e.g. Moore 1998; 1999;forthcoming). thatrevolve 8These questions around 'What kindof a worldis this?' are paraphrasing the sardonic to thegallows to be hanged and tragic, cryof Ken SaroWiwa whenhe was brought themechanism and he was brought backagain, and again, and he said'Whatkindof a failed, is this?' Packedin thosewords is a commentary not onlyon theincompetence of the country but on thejudgesand theprosecutors and the Nigerian hangmen, state, the whole apparatus himto death(see Soyinka thatcondemned 1996).

REFERENCES Academic Press. Abel,R. (ed.) 1982. Thepolitics ofinformal justice. (2 vols.)New York: F von 1979. Property Benda Beckmann, in social The Hague:Martinus continuity. Nijhoff. withK. von Benda Beckmann 1985.Transformation and changein Minangkabau. In

235-78.Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Center (eds) L. Thomas& F von Benda Beckmann, forInternational CenterforSoutheast AsianStudies. Studies, with 1994.Property, and conflict: AmbonandMinangkabau politics compared.

Law and Society Review28, 589-607.

in Minangkabau: and historical on WestSumatra Change and continuity local,regional, perspectives

Bohannan, P. 1957.Justice an(d judgment amongtheTiv. London: Oxford UniversityPress.

with & H. Spiertz In The role 1996.Water rights and policy. oflaw in natural resource 77-99.The Hague:Vuga. & M. Wiber, management (eds)J.Spiertz

accounts. Borneman, J.1997. Settling Princeton: University Press.

Bourdieu, P. 1977. Outlineof a theory ofpractice. Cambridge: UniversityPress.

SALLY FALK MOORE

113

LawJournal of thejuridical field. Hastings 1987.The force of law: toward a sociology 38, 814-53. Cambridge: in politicsand culture. Bowen, J. & R. Petersen (eds) 1999. Criticalcomparisons University Press. Press. oflaw.New York: Academic (eds) 1979. Theimposition Burman, S. & B. Harrell-Bond Berg. disputes. Oxford: Caplan,P. (ed.) 1995. Understanding M. & B. Garth(eds) 1978-9.A world (gen.ed.) M. (2 vols.), Access tojustice survey Cappelletti, & Nordhoff; Milan:A. Giuffre. vol. 1. Alphenaan den Rijn: Sijthoff Cappelletti, & state. Alphen aan den Rijn: Sijthoff. (eds) 1981.Accesstojusticeand theweffare Dobbs Ferry, & D. Tallon 1973. Fundamental of thepartiesin civillitigation. guarantees N.Y: Oceana. M. 1985 (1998). Law,custom Press. Cambridge: University andsocial order. Chanock, Stanford: University Press. 1973.Law andsocial change in Zinacantan. Collier,J. 4, 121-44. 1975.Legal processes.Annual ReviewofAnthropology In Profiles of landrights. of thecolonialperiodon thedefinition Colson,E. 1971.The impact and colonial in Africa (comp.) society rule(ed.) V. Turner,193-215,Colonialism ofchange: African L.H. Gann,vol. 3. Cambridge: University Press. sovereignty, subjectivity, of rights in colonialSouthAfrica: Comaroff, J. 1995.The discourse politics and rights (eds) A. Sarat& T. Kearns,193-236.Ann Arbor: modernity. In Identity, of Michigan Press. University 1991. Of revelation & J.Comaroff Chicago:University Press. and revolution. & and revolution, vol. 2. Chicago: UniversityPress. 1997. Of revelation Press. Chicago:University relationships. Chicago:University Press. Conley, J.& W O'Barr 1990.Rulesversus 1998.Justwords: & and power. Chicago: UniversityPress. law,language Press. cultural Durham, N.C.: Duke University lifeofintellectual properties. Coombe, R. 1998. Thle life. New York: Collier. formsof the religious Durkheim,E. 1961. The elementary precedent. Chicago: Aldine. Fallers,L. 1969.Law without law.London:Routledge& ChapmanHall. P. 1992. Themythology ofmodern Fitzpatrick, studies. Oxford: Blackwell. & A. Hunt (eds) 1987. Critical legal Tibet.Ithaca: Cornell University of Buddhist French,R. 1995. The goldenyoke:thelegalcosmology Press. andpractice. Press. University policy London:Cambridge Furnivall, J.1948. Colonial Delhi: Oxford Press. M. 1989.Law andsociety in modern India. University Galanter; New York: Basic anthropology. further essays in interpretive Geertz, C. 1983. Local knowledge: Books. Rhodesia.Manchester: amongthe Barotseof Northern Gluckman, M. 1955. The judicial process Institute. PressfortheRhodes Livingston University New Haven: Yale UniversityPress. 1965. T1e ideas in Barotse jurisprudence. law. Oxford: University Press for the in African customary (ed.) 1969.Ideas and procedures Institute. International African in the New Guinea Highlands. Hanover, N.H.: Gordon, R. & M. Meggitt 1985. Law and order Press of New England. University Press. Ithaca: CornellUniversity C. 1986.Praying for justice. Greenhouse, Press. notice. Ithaca: CornellUniversity 1996.A moment's societies in industrialized (Journalof Legal (ed.) with F Strijbosch.1993. Legal pluralism Pluralism 33, specialissue). of New StateUniversity & R. Kheshti andethnography. Albany: (eds) 1998.Democracy YorkPress. towns. American in three , B. Yngvesson & D.M. Engel (eds) 1994. Law and community Press. Ithaca: CornellUniversity

and justicein an African A. 1997. In theshadowof marriage: community. Chicago: gender Griffiths, & S. Roberts 1981. Rules and processes: context. logicof disputein an African the cultural

Press. University Law 24, 1-55. and Unofficial Journal ofLegalPluralism Griffiths, J.1986.Whatis legalpluralism? Boston: UniversityPress. in an African P. 1963. Social control society. Gulliver, Aldine. andsociety In Law in culture (ed.) L. Nader,11-23.Chicago: 1969.Introduction. Leiden: EJ. Brill. of Max Gluckman. essaysin memory (ed.) 1978. Cross-examinations: Boston: Beacon Press. and theevolution ofsociety. Habermas,J. 1979. Communication

114

SALLY FALK MOORE

I. (ed.) 1977. Socialanithropology Hamnett, and law (ASA Monograph 14). London:Academic Press. Hirsch, S. 1994. Kadhi'scourts as complexsitesof resistance: the state, Islam, and genderin In Contested 207-30.London: post-colonial Kenya. states (eds)S. Hirsch & M. Lazarus-Black, Routledge. court. Press. Chicago:University Press. Hoebel. E. 1954. Thelawofprimitive nman. Mass:HalvardUniversity Cambridge, Hooker, M. 1975.Legal plumlism. Oxford: University Press. Kelman, M. 1987.A guide tocritical legal studies. Cambridge, Mass:Harvard University Press. Kuper, L. & M.G. Smith (eds) 1969.Pluralismn inAfrica. of California Press. Berkeley: University

1998. Pronouincing and persevering: and thediscourse in an African gender of disputing Islamic

Institution Washington: Smithsonian Press. Llewellyn, K. & E. Hoebel 1941. The Cheyenne Ok.: University of Oklahoma way. Norman, Press. Low, D. 1996. The egalitarian moment: Asia and Africa, 1950-1980. Cambridge: University Press. D. (ed.) 1984. Theprospects Maybury-Lewis, societies of theAmerican forplural (Proceedings Ethnological Society, 1982)Washington, D.C.: American Ethnological Society. Law andSociety Merry, S. 1988.Legalpluralism. Review 22, 869-96. Press. Chicago:University Mertz,E. 1994. Legal language:pragmatics, poetics and social power.Annual Reviewv of

Anthtropology 23, 435-55.

and Barbuda. Lazarus-Black,M. 1994. Legitimate actsand illegal law and society inAntigua encounters:

1990. Getting justice and getting even: legal consciousness Americans. amongworking-class

In Biennial Review Moore,S.F 1969.Law and anthropology. of (ed.) B. Siegel,52Anthropology 300. Stanford: University Press. 1970. Politics, procedures and normsin changing Chagga law. Africa (October), 321-44. 1973.Law andsocialchange: thesemi-autonomous socialfield as an appropriate subject of study. Law and Society Revietv 7, 719-46. 1975a. Selectionforfailure in a smallsocial field:Kilimanjaro, 1968-69.In Symlbol andpolitics in communal 109-43.Ithaca:Cornell ideaology (eds) S.F Moore & B. Myerhoff, Press. University in situations: in culture. In Symbol and 1975b.Epilogue:uncertainties indeterminacies in communal 210-39. Ithaca:Cornell politics ideaology (eds) S.F Moore & B. Myerhoff, Press. University 1978.Law as process. London:Roudedge& KeganPaul. 1986a.Legal systems of theworld: an introductory guideto classification, typological In Law and the and bibliographical social interpretations, resources. sciences (eds) L. Lipson& 11-62. New York:RussellSage Foundation S. Wheeler, forthe Social Science Research Council. Press. University 1989a.History andpower in and theredefinition of custom on Kilimanjaro. In History thestudy & J.Collier, 277-301.Ithaca: CornellUniversity Press. oflaw(eds)J.Starr 1989b. The production 1: 2, 26-48. of cultural as a process. Public Culture pluralism 1998. Changing African land tenure: reflections on the incapacities of the state. 1999. Systematic forfuture accountjudicialand extra-judicial injustice: preparations

1986b. Socialfacts law on Kilimanjaro andfabrications: 1880-1980. Cambridge: 'custonmary'

European Journal of Developmnent Research 10: 2, 33-49.

126-51.London:Zed Books. Werbner, In Transnaandthecontext ofconditionality. international forthcoming.An legalregime tional Oxford: Press. legal process (ed.) M. Likosky. University L. (ed.) 1969.Law in culture andsociety. AldinePress. Nader, Chicago: Academic Press.

to the American New York: (ed.) 1980. No access to law: alternatives judicial system. 1990. Harmony ideology: in a Zapotec mountainvillage.Stanford: justice and control

and the critique ability.In Memoryand the postcolony: African anthropology of power (ed.) R.

Press. University 1992. From legal processingto mind processing.Familyand Conciliation CourtsReview 30, 468-73.

SALLY FALK MOORE

115

movementto re-formdispute ideology. The Ohio StateJournal on Dispute Resolution 9, 1-25. 1999. Pushing the limits:eclecticismon purpose. Political and LegalAnthropology Review

1993. Controlling in the practice processes of law: hierarchy and pacification in the

22, 106-10.

Newman, K. 1983. Law and economic organization: a comparative studyof preindustrial societies. O'Barr, W 1982. Linguistic evidence: power and strategy in the courtroom. New York: language, Peters, P. 1994. Dividing the commons; policy and culture in Botswana.Charlottesville: politics,

ColumbiaUniversity Press.

(ed.) with H. Todd 1978. The disputing process: disputing in ten societies. New York:

Press. Cambridge: University

Academic Press.

Pospisil,L. 1971. Anthropology of law: a comparative theory. New York: Harper & Row. Initernational Law Journal 40, 221-83.

University PressofVirginia. R. 1998. Pragmatic Posner, In The revival adjudication. ofpragmatism (ed.) M. Dickstein, 23553. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Riles,A. 1999.Wigmore's treasure box: comparative law in the era of information. Harvard R. & K. Mann (eds) 1991. Law in colotnial Roberts, Africa. Portsmouth, N.H.: Heinemann Educational. in a modernIslamiclegal system. Rosen, L. 1980-1.Equityand discretion Law and Society Review 15, 217-45. Press. Rouland,N. 1988.Anthropologie Paris: Presses de France. juridiqule. universitaires

1989. The anthropology ofjustice:law as culture in Islamicsociety. Cambridge: University

in theBritish WestIndies.Berkeley:University Smith,M.G. 1965. The pluralsociety of California

Press. F 1981a.Colonialism and legalform: thecreation of customary law in Senegal.Journal Snyder, of Legal Pluralism 19, 49-90. andpotver in the study CornellUniversity Press. J.& J.Collier1989.History oflaw.Ithaca: Starr, crowds. of California Press. Tambiah, Berkeley: University SJ. 1996.Leveling

1981b. Capitalism and legalchange. New York:Academic Press. Oxford: UniversityPress. Soyinka,W 1996. The opensoreof a continent.

1443-62. andsociety. M. 1978.Economy of California Press. Weber, Berkeley: University R. 1984. The Manchester School in South CentralAfrica.AnnualRevietw Werbner, of

Anthropology 13, 157-85. culture London: Pluto Press. and context. Wilson, R. (ed.) 1997. Human rights: London: Routledge. Yngvesson,B. 1993. Virtuous disruptive subjects. citizens,

and thepolitics Princeton:UniversityPress. Taylor,C. 1992. Multiculturalism of recognition. G. 1992.The two facesofJanus: Cardozo LauwRevieu.w Teubner, rethinking legalpluralism. 13,

2000. Reconciliation in post-apartheid SouthAfrica. Current and revenge Anthropology 41, 75-98.

Law and Society 1974-5. Smallclaims, Review & P. Hennessey 9, complexdisputes. 219-74.

Certitudes detruites: cinquante annees turbulentes d'anthropologie legale, 1949-1999

Re'sumn

j uridique du domainedes etudesde l'anthropologie Cet article passeen revuel'extension de cetteperiodeest 1949 et 1999,et considere les faqons dontl'arriere-plan politique entre Au milieudu siecle, les idees et les universitaires anglophones. dansles perspectives reflete leurs modesde gestion etplusspecialement pratiques non-occidentaux, juridiques despeuples coloniale. Deux ecolesde pensee de l'autorite etudiees dansle contexte etaient des conflits, L'une accordaune place centrale le passagedu temps. ont emergeet supporte principales L'autre donnaplus d'imnportance de la 1egalite. aux concepts culturels dansl'interpretation

116

SALLY FALK MOORE

et economique, des interets personnels. Les etudes au milieu politique ainsiqu'a la poursuite continuerent ensuite, mais a partir des juridiquesdans les conumunautes non-occidentales versles questions de classeet de dominaannees60 et 70 un nouveaucourant se tourna Une avancese produisit dansI'analyse quand tiondansles institutions 1egales occidentales. pas la seulesourcede normes obligatoires l'attention futporteesurle faitque l'Etatn'etait trouvaient leurorigineet ou le maiscoexistait avec beaucoupd'autres sitesou les normes de 'pluralisme social etaitexerce.Ce phenomene heterogene controle requtI'appellation larges de conception et engagees Un demi-siecle de travaux culmine dansdes etudes 1egal'. de l'homme, des conditions des droits prealables a la politiquement, qui se preoccupent et des obstacles a son implementation. democratie,

HarvardUniversity, WilliamJames Hall, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 02138, Department ofAnthropology, USA. Moore@wjh.harvard.edu

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The First Aegean Swords and Their AncestryDocument20 pagesThe First Aegean Swords and Their Ancestryaoransay100% (1)

- RICHTER Begriffsgeschichte and The History of IdeasDocument18 pagesRICHTER Begriffsgeschichte and The History of IdeasThaumazeinNo ratings yet

- Muslims in Early AmericaDocument41 pagesMuslims in Early AmericaLasana Tunica-ElNo ratings yet

- 69Document6 pages69Avilash Chandra DasNo ratings yet

- Product Catolgue CXWC PDFDocument3 pagesProduct Catolgue CXWC PDFAnthriqueNo ratings yet

- GT-S7562 User GuideDocument34 pagesGT-S7562 User GuideAnandCoolNo ratings yet

- Khaleda Statement. EdDocument2 pagesKhaleda Statement. EdAnthriqueNo ratings yet

- Neumann LectureDocument4 pagesNeumann LectureMiguelNo ratings yet

- Longines 5.686.4.71.2Document1 pageLongines 5.686.4.71.2AnthriqueNo ratings yet

- Power of TechnologyDocument21 pagesPower of TechnologyAnthriqueNo ratings yet

- IESS Neumann PDFDocument3 pagesIESS Neumann PDFAnthriqueNo ratings yet

- Asean & Saarc FrameworksDocument19 pagesAsean & Saarc FrameworksAnthriqueNo ratings yet

- PresentationDocument4 pagesPresentationAnthriqueNo ratings yet

- Education in Bangladesh - The Vision For 2025Document14 pagesEducation in Bangladesh - The Vision For 2025AnthriqueNo ratings yet

- Education in Bangladesh - The Vision For 2025Document14 pagesEducation in Bangladesh - The Vision For 2025AnthriqueNo ratings yet