Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Jean-François Lyotard

Uploaded by

allure_chOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Jean-François Lyotard

Uploaded by

allure_chCopyright:

Available Formats

JEAN-FRANOIS LYOTARD (192498)

FRENCH PHILOSOPHER

Jean-Franois Lyotard has long been recognized as one of the major figures in the development of postmodern thought. Although best known as a philosopher and cultural theorist, Lyotard also wrote extensively on the subject of art, producing numerous books, exhibition catalogues and essays over the course of his long career. His more general philosophical enquiries, particularly his concern with the concept of the sublime, also constitute important contributions to critical and aesthetic theory and artistic practice, and after considering the nature of those we shall move on to look at his writings on art in more detail. Postmodernism is to be considered as a generalized cultural reaction to received authority in all its various formssocial, political, intellectual and artistic. For Lyotard, Western history since the Enlightenment has been dominated by a series of metanarratives (or grand narratives) which have demanded our undivided loyalty. Both Marxism and liberal democracy are examples of such metanarratives in the political domain, although analogues can be found in other areas of discourse as well. Modernism, as a case in point, can be regarded as the metanarrative of artistic activity and aesthetic theory for the bulk of the twentieth century, and, in effect, claimed the right to legislate over artistic production during this period. Metanarratives command considerable authority, to the point where they can become tyrannical by enforcing conformity to a norm. In order to be taken seriously by their peers in the art world, for example, most twentieth-century artists had to paint in a modernist rather than a realist style; and to experiment rather than to continue to develop traditional modes of expression. It is against such enforced conformity that postmodernism is directed, its objective being to encourage diversity of expression in all areas of discourse instead of adherence to one supposedly superior metanarrative. Postmodernists, in other words, are champions of the cause of difference. Lyotards concept of the differend captures this commitment to difference very neatly. The differend is an irresolvable dispute between two parties: irresolvable because the parties are using incommensurable phrase regimens, or discourses, with their own internal criteria for deciding arguments. Put simply, their agendas are mutually exclusive, and the dispute will only be resolved if each agrees to respect the other and allow it to continue in its own way; or if, as more usually happens in the real world, one side imposes its will on the other and suppresses the opposing agenda. The overriding concern of Lyotards work is to encourage us to respect the differend, and thus, in his eyes, significantly to reduce political conflict. Lyotard is also committed to what he calls the event; that is, to the experience of the immediate moment, which is conceived always to be open and undetermined. It is one of the great failings of metanarratives that they are not open to the event, but claim to be able to forecast or determine its outcome (as in the

Key writers on art: The twentieth century

174

case of Marxisms theory of a dialectic inexorably working through human history towards a specific end). Art at its best for Lyotard makes us aware of the event and of the fact of difference. Lyotard displays an obsessive concern with the concept of the sublime over his later career, to the extent of writing an extended commentary on Kants writings on the topic (particularly the Critique of Judgement, 1790) entitled Lessons on the Analytic of the Sublime (1991). Building on the work of Kant, and other eighteenth-century theorists of the sublime such as Edmund Burke, Lyotard regards the sublime as a manifestation of the unpresentable. He treats it as the role of art to be in dialogue with this phenomenon: that there is something which can be conceived and which can neither be seen nor made visible: this is what is at stake in modern painting (The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge, 1979). For Kant and Burke, the sublime constituted that which lay beyond our human understanding (in Kants case, the realm of the noumenal or thing-in-itself). Concepts like infinity and totality could not, by definition, be representedthey were quite literally inconceivable. Our recognition of this failure of our understanding was a potential source of pain in our desire to make sense of the world around us. Burke in particular had a considerable impact on contemporary aesthetics, influencing a whole school of writers in later eighteenth-and early nineteenth-century Britainthe Gothic novel tradition. Gothic novelists such as Ann Radcliffe made extensive use of Burkes theories, with the formers many descriptions of the sublime landscape in her narratives drawing directly on Burke for inspiration. Burke had contended that, when confronted by objects of vast dimension or power, we were struck with a sense of awe; precisely what Radcliffes heroines experience when they are exposed to brute nature in their travels through the Alps and the Apennines (in The Mysteries of Udolpho or The Italian, for example). Lightning storms, waterfalls and sheer precipices make the Radcliffe heroine aware of her vulnerability and insignificance in the general scheme of things: nature far outstrips human capabilities, particularly the capabilities of the lone individual. The sublime constitutes a limit for both Kant and Burke, although the former is more exercised by this than the latter, given that it calls into question the overall viability of his philosophical projectto demonstrate how our world conforms to our concepts of it. Kant found himself wrestling with the problem that we can have a concept of, but not a conception of, infinity and totality. For Lyotard, too, the sublime is a limit, but it is one that we must accord respect rather than struggle against. Postmodernist thought in general is concerned to draw our attention to epistemological limits, and regards the faith placed in human reason by the Enlightenment project and its followers as excessive. In its concern with demarcating limits, postmodernism reveals itself to be an updated form of scepticism, pointing out the gaps in our claims to knowledge. (For a detailed study of the latter phenomenon, see Sim, Contemporary Continental Philosophy: The New Scepticism, 2000.) Lyotards writings on art are extensive, and reveal a deep and life-long interest in the topic. Rather surprisingly for someone concerned to challenge the cultural dominance of modernity and the modern, he shows a marked preference for the work of ostensibly modernist artists. Marcel Duchamp, the subject of Lyotards most extended study on the subject of art, is a case in point. Duchamps Trans/Formers (1977) is a collection of

Jean-Franois Lyotard

175

essays concentrating on two works of that artist: The Bride stripped bare by her Bachelors, even (The Large Glass), and Given: 1. The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas. It figures the unfigurable, Lyotard claims of the former, a figure that could not be intuitedat least that of a woman having four dimensions. Which is to say that the work presents the unpresentable. Lyotard goes on to praise the pointlessness of Duchamps work, the machinery of which, he argues, challenges the notion of a totalizing and unifying machine in any area of human endeavour. To resist totalization is to resist the project in which all metanarratives are engaged, thus bringing Duchamp under the heading of the postmodern. In his own way, Duchamp forces us to recognize the limits of our knowledge and the reach of our reason. Duchamps work is held to resist critical analysis, having for Lyotard something uncommentable about it that defeats the critic. What critics traditionally strive to do is to place artworks in historico-cultural context, such that they can be said to mean something in terms of the development of a particular metanarrative (the Enlightenment project, for example). Duchamps pointlessness prevents us from doing that, frustrating the impulse to systematize that lies at the root of the metanarrative of modernity. Faced by an artist like Duchamp, who is plainly refusing to conform to what is culturally expected of the artist, modernist or otherwise, the critic must cease to speak for the metanarrative, and, instead, try not to understand and to show that you havent understood. The critic acknowledges the limits of understandingyet another rejection of the Enlightenment ethos. Various other artists are praised by Lyotard for their ability to bear witness to the event and the fact of the differend. Paul Czannes Mont Sainte Victoire paintings are claimed to capture events directlywithout the mediation or protection of a pretext (Peregrinations: Law, Event, Form, 1988). Barnett Baruch Newmans paintings similarly seek to be the occurrence, the moment that has arrived (The Inhuman: Reflections on Time, 1988). Valerio Adami is another Lyotard favourite, an artist who can be observed stripping himself of our collective imagery in order to present us with a primal landscape as yet unmarked by the designs of metanarratives (The Lyotard Reader). In each case the artist has managed to escape the constricting effect of his metanarrative, and to convey a sense of the openness of the future to us. The ability to present the unpresentable becomes an index of aesthetic value for Lyotard. Modernism is no less capable of achieving this state than postmodernism; but modernism, Lyotard claims, does so reluctantly, communicating a feeling of nostalgia for a world where the fact of the unpresentable was not yet realized (or was ignored altogether), and organic unity was assumed to be achievable. In modern art, the unpresentable is put forward only as missing contents, whereas in postmodern art we realize that organic unity is an illusion and that the unpresentable is of necessity always with us (Postmodern Condition). The presence of that nostalgia helps us to discriminate between the modern and the postmodern, although it is important to note that these are not historically specific terms for Lyotard. Modernism and postmodernism are, instead, to be understood as cyclical movements: there have been modernisms and postmodernisms in the past, and there will be again in the future. At the moment, however, we are deemed to be squarely within a postmodern period, where the entire concept of metanarrative is under attack, and art is for Lyotard a critical way of revealing the shortcomings of the

Key writers on art: The twentieth century

176

metanarrative project. For the time being anyway, the sublime is firmly back on both the philosophical and artistic agenda.

Biography Jean-Franois Lyotard Born Versailles 1924. He taught philosophy at a high school in Constantine, Algeria, 195052, and at the Prytane Militaire de la Flche, 195259. In 1954 he joined the Socialisme ou barbaric group, and became the main writer on Algerian issues for the groups journal in 1955. He became a lecturer at the University of Paris, 195966; the University of Nanterre, 196670; and the University of Paris VIII, Vincennes, 197087 (where he was Professor of Philosophy from 1972 to 1987). He published The Postmodern Condition in 1979. Lyotard was Visiting Professor at (amongst other places) the University of California at San Diego and Berkeley, and at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, 19746; and at Yale University, 1992. He was founder-member of the Collge International de Philosophic, Paris, 1983 (President 19846). He died on 21 April 1998.

Bibliography Main texts The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge (La condition postmoderne: Rapport sur le savoir, 1979), trans. Geoffrey Bennington and Brian Massumi, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1984. Duchamps Trans/Formers (Les Transformateurs Duchamp, 1977), trans. I.McLeod, Venice, CA: Lapis Press, 1990. The Inhuman: Reflections on Time (Linhumain: Causerie sur le temps, 1988), trans. Geoffrey Bennington and Rachel Bowlby, Oxford: Blackwell, 1991. Peregrinations: Law, Event, Form , New York: Columbia University Press, 1988. Of the Sublime: Presence in Question (Du sublime, 1988; with others), trans. Jeffrey S. Librett, Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 1993. Reader: he Lyotard Reader , Andrew Benjamin (ed.), Oxford and Cambridge, Mass.: Blackwell, 1989. Secondary literature Benjamin, A. (ed.), Judging Lyotard , London and New York: Routledge, 1992. Bennington, G., Lyotard: Writing the Event , Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1988. Carroll, D., Paraesthetics: Foucault, Lyotard, Derrida , London: Methuen, 1987. Descombes, V., Modern French Philosophy (Le mme et lautre, 1979), trans. L.ScottFox and J.M. Harding, Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1980. Pefanis, J., Heterology and the Postmodern: Bataille, Baudrillard, and Lyotard , Durham, NC and London: Duke University Press, 1991.

You might also like

- Modernism and Postmodernism PostmodernisDocument15 pagesModernism and Postmodernism PostmodernisJoy Conejero NemenzoNo ratings yet

- Modernism and PostmodernismDocument18 pagesModernism and PostmodernismFitra AndanaNo ratings yet

- Avant-Garde and Neo-Avant-Garde: An Attempt To Answer Certain Critics of Theory of The Avant-GardeDocument23 pagesAvant-Garde and Neo-Avant-Garde: An Attempt To Answer Certain Critics of Theory of The Avant-GardesaucepanchessboardNo ratings yet

- The Origin of The Work of Art: Modernism: Heidegger'sDocument19 pagesThe Origin of The Work of Art: Modernism: Heidegger'siulya16s6366No ratings yet

- Introduction To Modernism and Postmodernism Edited AprilDocument35 pagesIntroduction To Modernism and Postmodernism Edited AprilAGUSTINA SOSA REVOLNo ratings yet

- Meaning and Significance of The HumanitiesDocument3 pagesMeaning and Significance of The Humanitiesbeeuriel0% (1)

- Represntation SemioticsDocument24 pagesRepresntation SemioticsDivya RavichandranNo ratings yet

- Image Evolution: Technological Transformations of Visual Media CultureFrom EverandImage Evolution: Technological Transformations of Visual Media CultureNo ratings yet

- METHODS OF PRESENTING ARTDocument65 pagesMETHODS OF PRESENTING ARTBpNo ratings yet

- PostmodernismDocument20 pagesPostmodernismIntzarEltlNo ratings yet

- 20th Century Art MovementsDocument11 pages20th Century Art MovementsAnonymous UwnLfk19OuNo ratings yet

- Aesthetical And Philosophical Essays by Frederick SchillerFrom EverandAesthetical And Philosophical Essays by Frederick SchillerNo ratings yet

- Postmodern LiteratureDocument14 pagesPostmodern Literatureapi-376795054100% (1)

- LyotardDocument52 pagesLyotardSipra MukherjeeNo ratings yet

- Oxford Art Online: Beardsley, MonroeDocument6 pagesOxford Art Online: Beardsley, Monroeherac120% (1)

- ANTHROPOLOGY - Components of CultureDocument10 pagesANTHROPOLOGY - Components of CultureMg Garcia100% (1)

- PostmodernismDocument17 pagesPostmodernismShweta Kushwaha100% (2)

- Originality of The Avant GardeDocument14 pagesOriginality of The Avant GardeHatem HadiaNo ratings yet

- Cultural HegemonyDocument4 pagesCultural HegemonyChristos PanayiotouNo ratings yet

- Research in Art and DesignDocument9 pagesResearch in Art and DesignSelena SavicNo ratings yet

- Hobbes and SpinozaDocument10 pagesHobbes and SpinozaVKNo ratings yet

- As Device: Notes On The Theory of Literature He SaysDocument8 pagesAs Device: Notes On The Theory of Literature He SaysRaphael ValenciaNo ratings yet

- ExpressionismDocument12 pagesExpressionismapi-193496952No ratings yet

- Deconstructivism & Contemporary PPT Ashish D & MD Ayazul - 1Document83 pagesDeconstructivism & Contemporary PPT Ashish D & MD Ayazul - 1ayaz khanNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 - Art and Nature of ArtDocument6 pagesChapter 1 - Art and Nature of ArtArthur LeywinNo ratings yet

- Vian Camille C. Lumanlan Humanities (Art Appreciation) Sir Nerson Ray RomeroDocument2 pagesVian Camille C. Lumanlan Humanities (Art Appreciation) Sir Nerson Ray RomeroVi AnNo ratings yet

- Art Appreciation Lesson 5Document14 pagesArt Appreciation Lesson 5Walter John AbenirNo ratings yet

- Phenomenology and StructuralismDocument5 pagesPhenomenology and StructuralismjosipavancasaNo ratings yet

- Deconstruction and FashionDocument8 pagesDeconstruction and FashionnitakuriNo ratings yet

- History of The Social Sciences - WikipediaDocument35 pagesHistory of The Social Sciences - WikipediaHanna Dee AlfahsainNo ratings yet

- Sva GR Entire CatalogDocument150 pagesSva GR Entire CatalogAura Cruz AburtoNo ratings yet

- Pop Art - Group 9Document20 pagesPop Art - Group 9Rechelle RamosNo ratings yet

- Defining ArtDocument2 pagesDefining ArtRoselyn TuazonNo ratings yet

- Pop ArtDocument24 pagesPop ArtCorina MariaNo ratings yet

- The Work of Art in The Age of Mechanical ReproductionDocument10 pagesThe Work of Art in The Age of Mechanical ReproductionVickiLoaderNo ratings yet

- Pop ArtDocument6 pagesPop ArtShowbiz ExposeNo ratings yet

- Chapter1 - Nature of HumanitiesDocument20 pagesChapter1 - Nature of HumanitiesRad BautistaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Humanities and Art Appreciation An IntroductionDocument8 pagesChapter 1 Humanities and Art Appreciation An IntroductionJoana mae AlmazanNo ratings yet

- Crimp - Appropriating AppropriationDocument8 pagesCrimp - Appropriating AppropriationSuzanne van der LeeNo ratings yet

- Syllabus of Fine ArteDocument33 pagesSyllabus of Fine ArteHector Garcia100% (1)

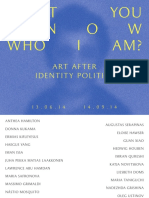

- Art After Identity PoliticsDocument107 pagesArt After Identity PoliticsMilenaCostadeSouzaNo ratings yet

- Journal of Visual Culture: Translating The Essay Into Film and Installation Nora M. AlterDocument14 pagesJournal of Visual Culture: Translating The Essay Into Film and Installation Nora M. AlterLais Queiroz100% (1)

- Self ExpressionDocument4 pagesSelf ExpressionGladys Lim Ruijia100% (1)

- Contemporary Art Styles MovementsDocument8 pagesContemporary Art Styles MovementsIzzy NaluzNo ratings yet

- Arts and Crafts Movement, de Stijl and CubismDocument8 pagesArts and Crafts Movement, de Stijl and CubismSamridhi SharmaNo ratings yet

- Stuart Hall 2Document11 pagesStuart Hall 2Bayangan Eks HumanNo ratings yet

- Post Colonial EssayDocument9 pagesPost Colonial EssayshalomtseNo ratings yet

- The Op Art (Optical Art) : Presented By: Basañez, Gabrielle Jasmin, Rheanne Jocson, Ronn Pimentel, Shiela May AsherDocument36 pagesThe Op Art (Optical Art) : Presented By: Basañez, Gabrielle Jasmin, Rheanne Jocson, Ronn Pimentel, Shiela May AsherasherNo ratings yet

- Material Thinking: The Aesthetic Philosophy of Jacques Rancière and The Design Art of Andrea ZittelDocument17 pagesMaterial Thinking: The Aesthetic Philosophy of Jacques Rancière and The Design Art of Andrea ZittelEduardo SouzaNo ratings yet

- Everyday Life and Cultural Theory An Introduction PDFDocument2 pagesEveryday Life and Cultural Theory An Introduction PDFChristina0% (1)

- Lesson 1-Art AppreciationDocument18 pagesLesson 1-Art Appreciationalexanderaguilar2735No ratings yet

- What Drawing and Painting Really MeanDocument29 pagesWhat Drawing and Painting Really MeanJoão Paulo Andrade100% (1)

- Loveless PracticeFleshTheoryDocument16 pagesLoveless PracticeFleshTheoryPedro GoisNo ratings yet

- Performance Art Is Art in Which The Actions of An Individual or A Group at A Particular Place and in A Particular Time Constitute The WorkDocument4 pagesPerformance Art Is Art in Which The Actions of An Individual or A Group at A Particular Place and in A Particular Time Constitute The WorkNisam JaNo ratings yet

- Aesthetics of PlatoDocument34 pagesAesthetics of PlatonagthedestroyerNo ratings yet

- (HOUSEN, Abigail) Art Viewing and Aesthetic Development Designing For The ViewerDocument18 pages(HOUSEN, Abigail) Art Viewing and Aesthetic Development Designing For The ViewercamaralrsNo ratings yet

- Herbert Marcuse One-Dimensional Man PDFDocument13 pagesHerbert Marcuse One-Dimensional Man PDFChirag Joshi100% (2)

- The Two Souls of Socialism - Hal DraperDocument29 pagesThe Two Souls of Socialism - Hal DraperoptimismofthewillNo ratings yet

- Soviet Uniforms - Man 1940-42Document2 pagesSoviet Uniforms - Man 1940-42allure_chNo ratings yet

- Grigory GrabovoyDocument3 pagesGrigory Grabovoyallure_chNo ratings yet

- What Are We Made ofDocument6 pagesWhat Are We Made ofallure_chNo ratings yet

- The Senses and SpeechDocument6 pagesThe Senses and Speechallure_chNo ratings yet

- Soviet Uniforms - Man 1945Document2 pagesSoviet Uniforms - Man 1945allure_chNo ratings yet

- Brand Value and The Circulation of MeaningDocument4 pagesBrand Value and The Circulation of Meaningallure_chNo ratings yet

- Media Power, Ideology and MarketsDocument2 pagesMedia Power, Ideology and Marketsallure_ch67% (9)

- Silence and Strategy Researching AIDS HIVDocument15 pagesSilence and Strategy Researching AIDS HIVallure_chNo ratings yet

- Soviet Uniforms - WomanDocument3 pagesSoviet Uniforms - Womanallure_chNo ratings yet

- Imagined CommunitiesDocument3 pagesImagined Communitiesallure_chNo ratings yet

- Benedict Andersons Definition of NationDocument1 pageBenedict Andersons Definition of Nationallure_chNo ratings yet

- What Does (The Study Of) World Politics Sound LikeDocument22 pagesWhat Does (The Study Of) World Politics Sound Likeallure_chNo ratings yet

- Soviet Uniforms - Woman 1941-43Document2 pagesSoviet Uniforms - Woman 1941-43allure_chNo ratings yet

- In A Pomegranate ChandelierDocument5 pagesIn A Pomegranate Chandelierallure_chNo ratings yet

- Videogames and IR, Playing at MethodDocument7 pagesVideogames and IR, Playing at Methodallure_chNo ratings yet

- Cultural Analysis of A HealthDocument8 pagesCultural Analysis of A Healthallure_chNo ratings yet

- New Technologies and Cultural FormsDocument2 pagesNew Technologies and Cultural Formsallure_chNo ratings yet

- Protests, Demonstrations and EventsDocument20 pagesProtests, Demonstrations and Eventsallure_chNo ratings yet

- Roots of Radical FeminismDocument17 pagesRoots of Radical Feminismallure_chNo ratings yet

- Popular Perceptions of MedicineDocument28 pagesPopular Perceptions of Medicineallure_chNo ratings yet

- T. Monk Lets Cool OneDocument2 pagesT. Monk Lets Cool Oneallure_chNo ratings yet

- Iranian Validation of The Identity Style InventoryDocument15 pagesIranian Validation of The Identity Style Inventoryallure_chNo ratings yet

- The Role of Parenting and Attachment in Identity Style DevelopmentDocument12 pagesThe Role of Parenting and Attachment in Identity Style Developmentallure_chNo ratings yet

- Two Languages Two MindsDocument17 pagesTwo Languages Two Mindsallure_chNo ratings yet

- Thelonious Monk Institute of JazzDocument3 pagesThelonious Monk Institute of Jazzallure_chNo ratings yet

- Thelonious Monk Is This HomeDocument6 pagesThelonious Monk Is This Homeallure_chNo ratings yet

- Military Videogames, Geopolitics, MethodsDocument7 pagesMilitary Videogames, Geopolitics, Methodsallure_chNo ratings yet

- Thelonious Sphere MonkDocument3 pagesThelonious Sphere Monkallure_chNo ratings yet

- Videogames and IR, Playing at MethodDocument7 pagesVideogames and IR, Playing at Methodallure_chNo ratings yet

- Narrative After DeconstructionDocument205 pagesNarrative After DeconstructionBianca DarieNo ratings yet

- (Stuart Sim) Lyotard and The Inhuman (Postmodern EDocument82 pages(Stuart Sim) Lyotard and The Inhuman (Postmodern EThiago Cardassi Sanches100% (1)

- PostmodernismDocument9 pagesPostmodernismMalkish Rajkumar100% (1)

- IJRHAL-Format - Postmodernism in The Age of Darkness Examining Dharamvir Bharati's AndhaYugDocument10 pagesIJRHAL-Format - Postmodernism in The Age of Darkness Examining Dharamvir Bharati's AndhaYugImpact JournalsNo ratings yet

- کتیب ملخص المؤتمر الدولي السنوي الرابع حول القضايا الراهنة للغات، علم اللغة، الترجمة و الأدبDocument41 pagesکتیب ملخص المؤتمر الدولي السنوي الرابع حول القضايا الراهنة للغات، علم اللغة، الترجمة و الأدبAhwaz Conference / مؤتمر الأهوازNo ratings yet

- The Post Modern ExplainedDocument12 pagesThe Post Modern ExplainedIvy Siu Pui TingNo ratings yet

- Argumentative Essay PostmodernismDocument7 pagesArgumentative Essay PostmodernismPatricia CopelloNo ratings yet

- Callinicos Social TheoryDocument195 pagesCallinicos Social TheoryRu Gi100% (2)

- Postmodernism DU ProfDocument19 pagesPostmodernism DU ProfTanmay SinghNo ratings yet

- Narrating Truths of Turmoil: 'Metanarratives' From A Con Ict Analysis PerspectiveDocument15 pagesNarrating Truths of Turmoil: 'Metanarratives' From A Con Ict Analysis PerspectiveDesi NoobsNo ratings yet

- Part 2 - Philo Oral Compre ReviewerDocument28 pagesPart 2 - Philo Oral Compre ReviewerJonathan RacelisNo ratings yet

- Traditionsin Political Theory PostmodernismDocument20 pagesTraditionsin Political Theory PostmodernismRitwik SharmaNo ratings yet

- Linguistic VirusDocument302 pagesLinguistic ViruszxcvbsNo ratings yet

- Isnt It IronicDocument132 pagesIsnt It IronicNiels Uni DamNo ratings yet

- Theory Psychology-2014-Adams-93-110Document18 pagesTheory Psychology-2014-Adams-93-110Malahat HajiyevaNo ratings yet

- Postmodernism, or The Anxiety of Master NarrativesDocument18 pagesPostmodernism, or The Anxiety of Master Narrativesanon_536700750No ratings yet

- SHAW - Technoculture The Key ConceptsDocument218 pagesSHAW - Technoculture The Key ConceptsGue Martini100% (2)

- T H e Pattern Language and Its Ene Es: Kimberly DoveyDocument7 pagesT H e Pattern Language and Its Ene Es: Kimberly DoveyRamez RezayiNo ratings yet

- Asian Perspectives AteneoDocument25 pagesAsian Perspectives AteneoJasmine Bianca CastilloNo ratings yet

- PostmodernismDocument9 pagesPostmodernismAlanNo ratings yet

- 17 - Hooti, Noorbakhsh - A Postmodernist Reading of Tom Stoppard's Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead PDFDocument16 pages17 - Hooti, Noorbakhsh - A Postmodernist Reading of Tom Stoppard's Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead PDFciccio pasticcioNo ratings yet

- Hariharasudan (201110204) PDFDocument248 pagesHariharasudan (201110204) PDFvinitha k.lNo ratings yet

- Postmodern EpistemologyDocument40 pagesPostmodern EpistemologyVinaya BhaskaranNo ratings yet

- Understanding PostmodernismDocument15 pagesUnderstanding Postmodernismames100% (1)

- Anthropological Theories PDFDocument150 pagesAnthropological Theories PDFSoumya Samit samal100% (1)

- The Chaos Behind Pulp FictionDocument6 pagesThe Chaos Behind Pulp FictionSoul_corruptionz100% (1)

- Re Envisioning Tribal Theology EngagingDocument21 pagesRe Envisioning Tribal Theology Engagingsimon pachuauNo ratings yet

- Report On Literary Major WorkDocument7 pagesReport On Literary Major WorkMichael SunNo ratings yet

- The Lakota Shamanic TraditionDocument31 pagesThe Lakota Shamanic TraditionJames Iddins88% (8)

- Richard Bauckham - Scripture and Authority (1998)Document8 pagesRichard Bauckham - Scripture and Authority (1998)Jona ThanNo ratings yet