Professional Documents

Culture Documents

DeNORA, Tia (2004) - Historical Perspectives in Music Sociology PDF

Uploaded by

lukdisxitOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

DeNORA, Tia (2004) - Historical Perspectives in Music Sociology PDF

Uploaded by

lukdisxitCopyright:

Available Formats

Poetics 32 (2004) 211221

Historical perspectives in music sociology

Tia DeNora

Department of Sociology, SHiPSS, University of Exeter, Exeter EX4 4RJ, UK

Abstract Over the past twenty years, historical perspectives in music sociology have linked music to a wide range of social processes. These include the material culture of performance and reception, distribution organisation, critical discourse and music education, the social shaping of musical style, the politics of taste and patronage, and the changing nature of the musical audience, music reception, reputation, authenticity, innovation. This work has partially overlapped with new musicology and its deconstruction of the idea of aesthetic autonomy. More recently, new topics have been drawn into the frame including: music as a medium of political action, musics role in relation to the history of science and the body, and music as a technology of identity and memory. In all of these areas, musics presence is highlighted as a resource for social ordering, in particular as an agent of psycho-cultural change. # 2004 Published by Elsevier B.V.

1. Music and its status in social theory and sociological enquiry Since this article covers historical perspectives in music sociology, it seems tting to begin with a brief recollection. One of the rst articles I read as a new graduate student in 1984 was Richard Petersons signal (1979) article, Revitalising the culture concept. I had begun my programme at UCSD, like many new students, quite certain of the project I wished to pursue a critical appraisal of experimental music after 1950, seen in light of Adornos concepts of the progressive and reactionary compositional tendencies in 20th century music. Luckily for me, and thanks to my teachers who initially placed Petersons article under my nose, I soon abandoned that topic. The Peterson piece not only offered a gallery of new methodological procedures for cultural sociology, it also sketched a theory of culture and its link to structure that (so unlike Adorno) was devoted to specifying connections between that culture, social relations, institutional arrangements and technologies at the actual, situated, level of practice. In

E-mail address: tdenora@exeter.ac.uk (T. DeNora). 0304-422X/$ see front matter # 2004 Published by Elsevier B.V. doi:10.1016/j.poetic.2004.05.003

212

T. DeNora / Poetics 32 (2004) 211221

short, that piece taught me that to understand how culture is shaped and how it works it is necessary to examine the tangible and often minute processes of producing, distributing and consuming cultural products. Anything else is, at best, hypothetical and, at worst, self-indulgent in so far as it posits historical realities leaves ungrounded (see DeNora, 2000:15). The late 1970s and 1980s were watershed years for historical music sociology. The production of culture tradition (described in detail by Dowd this volume) dramatically reshaped cultural sociology. With respect to historical work on music, it proposed new ways of exploring musical styles and works from within the practical and institutional contexts of their making. Peterson and Bergers study (1975), in which innovation was linked to cycles of production organisation, Beckers Art Worlds (1982) and Cerulos (1984) study of social forces and musical styles all highlighted how change in musical styles could be understood as taking shape in relation to the available conventions and ways of crafting within production networks or worlds of practice. All of these researchers located the social shaping of art works much closer to prosaic matters involved in getting things (any sort of things) done the interaction order, materials, patterns and institutions of music making, gatekeepers and arbiters, technologies. They effectively re-materialised culture, reminding us that (a) culture was more than ideas and values and (b) that cultures relation to structure could not be handled adequately by assuming a homology between the two. They also showed that the often overlooked, practical (and proximal) features of musical work provided a matrix of the possible/ probable of musics development, and that these features were far more prescient as determinants of cultural forms than distal forces such as whether an artists or composers home country is at war, or whether she espouses or is enmeshed in a particular economic, religious or political ideology. At last it was possible to theorise culture in grounded ways, and to begin to speak with more precision about links between music, social structure and change over time. This theme was further elaborated by some highly innovative work on music classication and the articulation of social boundaries. William Webers research on the connections between social groups and repertory in Europe (1975) and Paul DiMaggios (1982) study of cultural entrepreneurship in Boston both showed how the musical canon was established through the work of elite music activists and how the new music practices of distribution and consumption they fostered led to forms of social exclusion and hierarchy within and beyond musical life. These hierarchies were not merely about class and cultural capital; they were, for musicians, composers and performers, gendered in their consequences as Citron (1993) has shown. My own work on Beethoven (1995) can also be lodged here. I wanted to examine the canonic ideology which later served as a resource for taste makers in pan-European and American context as it was initially articulated. This meant a focus on cultural change inthe-making, rather as Bruno Latour advocated for Science in action (1987). I focused therefore on the organisational basis and its proclivity for the concept of greatness, on the social connections and career patterns of Beethoven versus his contemporaries and on the interactive, linguistic, programming and technological practices through which Beethoven came to assume the mantle of Europes premier composer. These changes in music ideology were accompanied by new ways of apprehending music, and this topic was

T. DeNora / Poetics 32 (2004) 211221

213

explored with great nesse by James Johnson (1995) whose study of listening in Paris chronicled the shift from casual, inattentive and sometimes irreverent listening to rapt silence in the face of great music during the 19th century.

2. Historical music sociology and musicology Both sociologists and musicologists have sought to deconstruct the canon in the musicological toolbox, as the music historian Donald Randel has termed it (1992), though we have conducted this work in quite different ways. For better and worse, we sociologists have mostly avoided analysis of musical works (whether as scores or performances) per se (think, for example, of the essays collected in Leppert and McClary, 1987). Instead, we have focused on the pragmatic bases for musical developments, sticking close to what people do, what they say, and to patterns of production, distribution and consumption. And when we have examined works, it has been from the perspective of their social shaping. Since the path breaking studies of the 1980s, we have dealt with a wide range of topics. These include the shape of individual musicians careers (Elias, 1993, on Mozart), cultures of listening (Johnson, 1995 on 19th century Parisian concert life), social control (Russell, 1987) and music technologies (DeNora, 1995; Pinch and Trocco, 2002). In short, a great deal of work has been accomplished in historical music sociology. And yet, when I interact with musicologists, their chief complaint about music sociology is that we do not take music seriously. There is a grain of truth to this criticism: we have not paid sufcient attention to the role of musical sound and its performance in social ordering in general and, more specically, to the role of organised sound as a dynamic medium in relation to historical process and to cultural and political change. In other words, there has been a good deal written about the social shaping of music (its context of production and its various appropriations for identity politics and distinction). There has also been a lot published on music and afliation, music and social boundaries. But there has been much less said about how musics specically musical properties may be involved in social processes or ordering and re-ordering and when there has (by cultural studies, by musicology) this focus is text-based, too concerned in my view with what individual works might mean rather than with what they might make possible. Music, in other words, is either ancillary to other social projects (such as distinction and boundary work) or it is treated as a nite (and implicitly impassive) object, either to be explained (its social shaping) or read (as if it contains meaning). I nd this an odd state of affairs. We know musics specic properties have counted a great deal in past times the history of music in the West, for example, is punctuated with attempts to enlist and censure musics powers and much of this activity have centred on how sound is performed and/or organised in composition. (Think, for example of Shostakovichs commission for a symphony to mark the anniversary of the Russian revolution as compared to his later censure for writing decadent music, or the banishment of atonal music in Nazi Germany, or, in more recent times, the furore over national anthem renditions [the Sex Pistols God Save the Queen or Jimi Hendrixs version of the Star Spangled Banner] all attest to the idea that music can instigate consensus and/or subversion.)

214

T. DeNora / Poetics 32 (2004) 211221

These are not issues, though, that can be explored adequately with the traditional tools of new musicology, namely, music criticism and the interpretation of texts because, as we now acknowledge, readings, are inevitably performative not descriptive of those texts (see, e.g., DeNora, 1986, 2000 chapter 2; Martin, 1995). At the same time, we can learn a great deal from collaboration with musicologists. This learning process, if it is to be truly successful, requires adaptation on both sides. We should no more seek to collapse our perspective into musicology than to expect the musicologists to abandon their concern with musical scores and performance practices. Instead, a genuine interaction needs to occur. Antoine Hennion (1995) has outlined one form this interaction might take, suggesting that it is now time to move beyond musicologising musics effects (by reading off what music might cause from texts) while also moving beyond sociologising musics specically musical properties (where we dismiss musics dynamism as an agent of social ordering and suggest that musics meaning or emotional powers are merely attributions). Hennion has suggested a much more cooperative project, one that retains both disciplines specic foci. With this I fully concur. On the one hand, sociologists have highlighted just how useful it is to consider the culture-structure nexus in terms of specic practices. They have highlighted how these practices create links, or articulations, between forms of music and forms of life. And they have underlined the importance of illuminating actual articulations. As Hennion puts it (1995), it must be strictly forbidden to create links when this is not done by an identiable intermediary. On the other hand, the musicologists remind us that social life is not merely socially constructed, but is crafted with reference to materials, conventions and technologies, of which music is one, and that these materials may mediate the things that are done with and to them. How, then, might we develop historical music sociology in the 21st century, in ways that highlight musics role as an agent of social ordering and social change? And how might this be done while holding on to the grounded, populated approach honed by sociology of culture over the past twenty-ve years? I would like to suggest that these questions can only be answered via situated studies. To that end, for illustrative purposes, I want to return to terrain I have covered many times Beethoven in late 18th and early 19th century Vienna.

3. Music, experience, consciousness and subjectivity In a discussion of musics rise within the arts during the 19th century (and in relation to Liszts championing of Beethoven in performance), the music and cultural analyst Richard Leppert (1999:253) has ventured: . . .for the first time in Western history, the cultural pecking order of the arts was rearranged so that music, formerly judged lesser than the textual and visual arts, was considered pre-eminent. Music was the sonorous sign of inner life, and inner life was the sign of the bourgeois subject, the much heralded, newly invented, and highly idealised individual. The European gold standard of the sonorous inner life was quickly and generally established as Beethoven

T. DeNora / Poetics 32 (2004) 211221

215

I nd this passage fascinating. To me Leppert is suggesting (in keeping with classical social theory) that modern social institutions both inculcate and depend upon the notion of the individual subject, that is, actors characterised by interiority and the capacity for selfdetermination. Self, understood as individual identities and their subjective and embodied properties, is both a social construct of and social obligation in modern societies (Giddens, 1991). From this idea arise various empirical questions that deal with the cultural production of subjectivities and the resources for this production. They highlight a case for why historical music sociology needs, in my view, to equip itself for the study of, as it has been termed within critical theory, psycho-cultural change. The term psycho-cultural refers to the pre- or non-conscious features of social orientation and styles of cognitive orientation (for example, critical orientation or acquiescence). While the concept of psycho-cultural is intriguing, it is also in need of further specication and this is what I now wish to consider using music, and Lepperts comment, as a case in point. First, if there is a sonorous inner life, might it be useful to also think about its external corollary in terms of, for example, not necessarily conscious forms of behavioural and embodied practice? Second, how might inner and outer be linked how, for example, might new forms of expression provide resources for new forms of inner life? Third, can questions such as these be pursued in ways that retain and make use of the methodological advances bequeathed to music sociology by the production and worlds approaches and by the empirical tradition of reception studies? On this last point, Lepperts focus gives a new twist to music sociologys concern with the social shaping of music. No longer focused on how musical works are produced and valued, it is, by contrast focused on how selves and their associated subjectivities (emotions, feeling and embodied states) are produced and valued and how music can be involved in this process. Applying this focus to historical music sociology, as Lepperts comment implies, and using the three questions I have just outlined above, I suggest it is possible to develop historical music sociology in ways that remain dedicated to a study of the actual practices of specic people over time. Accordingly, in the next two sections I address these questions in reverse order, however, since I think that the methodological issues help to clarify the theoretical ones about the nature of consciousness, subjectivity and the changes in these things over time.

4. Method? The musicologist Scott Burnham has identied Beethovens music as the lynch pin around which new images and conventions concerning the self and the individual were articulated during the 19th century. These notions include the concept of the heroic in music (and the musician as hero, that is as demonstrating various forms of technical and social mastery). Also included was the idea of the powerful and autonomous artistindividual, the notion of the composer and/or musician as one who startles his audience and as someone engaged in moral (and visible physical) struggle, and the idea of music as a quest. Burnhams work is intriguing from an historical sociological perspective because he is concerned with psycho-cultural phenomena as they were represented and indeed

216

T. DeNora / Poetics 32 (2004) 211221

instigated by Beethovens musical rhetorical practices. Burnham is, foremost, a musicologist and cultural historian and, accordingly, his work does not delve into the music producing, distributing and consuming worlds in which these representations were enacted, revised and internalised. We do not learn, for example, about the experience of Beethoven, socially situated in terms of consumption. And yet, an exploration of just these issues can help to ground the emergence of new forms of musical subjectivity at the level of practice which is to say, at a level at which the mechanisms of psycho-cultural change may be illuminated. Moreover, attempting to focus on how Beethovens contemporaries performed and dened their experience of his music simultaneously is overtly an approach that tries (not always successfully, not always fully) to be explicit about the source of attributions to Beethovens music namely, from his contemporaries or from us. (Hennion and Fauquet (2001:7778) make a similar point in their study of Bach and his grandeur when they speak of how they wish to avoid proposing yet another, unexplored approach to deciphering [Bach]. By contrast, they say, it is this relationship that we wish to reveal, rather than exploit by proposing another in a long line of Bach-interpretations (see also Fauquet and Hennion, 2000]. By this they mean they wish to follow other, historically located agents as they make Bach meaningful to themselves and others, not to merely add another interpretive layer.) How, then, methodologically, might we lodge Burnhams concerns at the level of the production, distribution and consumption of Beethovens music? Did physical practices of music making inform the linguistic and critical discourses through which Beethovens work came to be evaluated and discussed (for discussion of the relation between tacit practices and linguistic discourses see Biernacki, 1995)? If Beethovens music was associated with psycho-cultural changes related to the self in modern societies, is it possible to specify how his music and its performance entered and informed that process? For if it is not possible to ground the meaning of these things, and to trace them in action and production organisation, then it is also not possible to explain the mechanisms through which music works. One way of grounding Burhhams topic is by focusing on its external expression in musical practice. Who, for example, performed Beethoven and how and with what reactions? For if music was a realm in which new (and not necessarily conscious) notions of the self were articulated in the early 19th century, we should be able to observe the external correlates of this process in musical occasions and events. While various sites provide opportunities for examining embodied display (dance, dining, promenading, physical pursuits such as riding), one of the best places to observe the enactment of embodied and emotional attitudes was in music performance where listeners were gathered specically to observe visually and aurally. While action on the stage (opera; drama) offered a similar opportunity, in music, physical action was, ostensibly, ancillary to performance. And yet, the actions of performers (their performance of performance, in other words) was noted and discussed. Piano performance was thus an opportunity to delineate meanings (see Green, 1997 for a discussion of delineated meaning) about the nature of virtuosity but also meaning more broadly about the nature of the performing self. The piano in late 18th and early 19th century Vienna provided a focal point for discussion and debate about aesthetic practice. It was a site at which new and often

T. DeNora / Poetics 32 (2004) 211221

217

competing aesthetics were deployed and defended, at times through the overt medium of the piano duel (DeNora, 1995, Chapter 7). I have described elsewhere (DeNora, 2002; DeNora, 1995) the ways in which Beethovens piano music and its performance challenged earlier notions of music aesthetics listening and performing. Performances of Beethovens piano music its manly style as one observer put it involved a more visible and more muscular body at the piano. In this way they sketched the lineaments or external markings of new ways of being a piano-performing subject a particular type of energetic, strong and surprising performer. In this way, we see at the level of musical practice how Beethovens music may have helped forge new psycho-cultural and physically embodied stances, a new, active self characterised by physical prowess. We can also observe how this orientation and its physical-practical expression was socially distributed, at least along gender lines. While women were highly active on the piano concert stage in every sense, including in the performance of concertos, they most overwhelmingly did not perform Beethovens concertos. In my lists so far of who performed Beethoven between 1973 and 1810, only one woman performed a Beethoven concerto Josepha Auernhammer, who, viewed both through her own eyes and through the eyes of her contemporaries, was perceived as fat and as no beauty (for discussions of the data so far, see DeNora, 2002 and DeNora, forthcoming). Were the new habits of self-presentation, and the responses they sought to elicit incommensurate with conventional femininity? And if so, was music one of the media through which ideas about mens and womens place in modern public life were dramatised? I believe this was the case (DeNora, 2002): during the 19th century, women came to be increasingly associated with a stereotypically feminine world of decorative and sweetly plaintive expression, contrasting with the gigantic outbursts of Beethoven or the dazzling virtuosity of Liszt and Thalberg (Ellis, 1997:364). And there are interesting connections here with the ways in which the social distribution of musical material in opera during the 1780s also reinforced new, post-enlightenment notions concerning the nature of the sexes (see Wheelock, 1993; DeNora, 1997) showing us how the production of music and science may be seen, reciprocally, to draw upon each other. Music may have helped to delineate new subjectivities and their external correlates as conventions of (musical) action, in other words, but access to these was not open to all musical practitioners.

5. The outer/inner sonorous life I have been trying to highlight how a focus on music in performance/reception helps to ground the meaning of the term sonorous inner life by tracking its external correlates in musical practice over time for example, what was new, shocking, old hat, out of place, illjudged or timed, exciting, excellent, inept? Through discussions about music, social meanings and distinctions (such as heroic or masterful) come to be associated with musical gestures and musical materials. Beyond these associations, modes of attention (such as rapt silence, surprise, awe) come to be paired with these practices and their meanings.As Simon Frith once put it:

218

T. DeNora / Poetics 32 (2004) 211221

in Adam Bede, George Eliot writes of her teenage heroine: Hetty had never read a novel: how then could she find a shape for her expectations? Nowadays our expectations are shaped by other media than novels, by film and television fictions, by pop stars and pop songs. Popular culture has always meant putting together a people [CHECK quote] rather than simply reflecting or expressing them. . . (1990:424). Frith speaks about popular music. While Beethovens music rarely fullled the criterion of popular in his lifetime, it nevertheless provided a focal point for its observers and in this sense, Friths words have resonance for psycho-cultural change and its relation to musical practice in early 19th century Vienna. However, it is one thing to assert that music shapes expectations. It is quite another to document this process as it actually happens at the level of practice. It is here, that scholars such as Frith can help lead the way. It is also here that musicology can make use of sociological methods and techniques, and in the nal section of this article I want to pursue the topic of how music may inform or otherwise structure subjectivity through a discussion of current work addressed to that question. In recent years, these issues have been explored by music sociology (Gomart and Hennion, 1999; DeNora, 2000; Bull, 2000). These studies have examined the practices by which actors consume and use music, sometimes with careful deliberation, sometimes unconsciously, and in ways that are consequential for the phenomenological features of the self memory, emotion and corporeality. In short, they illuminate music as it is used to congure inner lifes emotional and embodied corollaries, for example as when actors use music to prime themselves for particular action styles. Music provides (and is described by respondents as providing) a template against which to feel, a material one can turn to for engaging in emotional work, in work upon the self self-regulation and self-ordering. In the production of this work actors attune to some very specic musical properties properties both of musics compositional arrangement and its performative handling (i.e., how musical parameters are rendered in performance) melodic structure, rhythm, pace, harmonic structure, genre (e.g., love songs, dance music), phrasing, performer-gesture, chosen tempo or orchestration and so on.

6. Music in (historical) action and cognition; music as an agent of change over time There is a growing body of work devoted to musics role in relation to the organisation of action and to social and psycho-cultural change, in particular the ways in which music is linked to activism. Ron Eyerman and Andrew Jamieson have discussed just this issue in their 1998 book, Music and Social Movements. They critique overly cognitive models of movement activity and suggest that, in the case of 1960s activism, music can be seen to provide exemplars for action and at times may presage or pregure action. For example, they describe how Todd Gitlin, president of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) in the 1960s, described the SDSs identication with the music of Bob Dylan (we followed his career as if he were singing our song; we got in the habit of asking where he was taking us next [p. 116]).

T. DeNora / Poetics 32 (2004) 211221

219

The concern with musics musical and performative properties and their impact upon social and political action is increasingly taking root in areas that are not overtly concerned with music. Social movement theory is one, the history of political activism another (Stomatov, 2002). Stomatovs examination of how political activists were able to appropriate Verdis operas during the 1840s, thereby framing possibilities for aesthetic experience, illustrates how musical framing may be linked to capacities for political afliation and how musics social force is constituted through an admixture of musics properties and the ways those properties are accessed and foregrounded through music appropriation and music presentational devices. Similarly, on-going work by Roy (2003) and forthcoming work by Roscigno and Danaher (2003) follows music as it is acted upon and used to encourage modes of political involvement.

7. Conclusion Historical music sociology has moved, over the past three decades, from grand but ungrounded perspectives to grounded perspectives that showed us the institutional and organisational bases of musical production, consumption and distribution. More recently, the eld has reconsidered the concerns of musicologists and the focus on musics musical and performative properties and their links to the articulation of subjectivities across time and space. Both music scholars and sociologists are converging on, as Lawrence Kramer puts it, . . .the way music helps shape historically specic modes of subjectivity on grounds that are, taking the term in its broadest sense, ideological (2003:126). In short, we have moved away from a sociology of music to a consideration of music as a dynamic medium of social ordering. In short, music sociology, recently conceived, has helped to elaborate the ways in which non-propositional media may provide resources for the articulation of agency, ordering and of our conception of the (often tacit) dimensions of these things locally congured. In this respect, music sociology overlaps with other areas in cultural sociology concerned with the ways that objects and their use may structure social relationships, consciousness and subjectivity. As scholars outside the immediate eld of music sociology grow increasingly interested in the cultural and psycho-cultural basis of action and agency for example, organisational subjectivity, the role of emotions in political action we shall perhaps see a great deal more interaction between music sociology, historical music sociology and sociology writ-large.

References

Becker, Howard, S. 1982, Art Worlds. University of California Press, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London. Biernacki, Richard, 1995. The Fabrication of Labor. University of California Press, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London. Burnham, Scott, 1995, Beethoven Hero. Princeton University Press, Princeton. Bull, Michael, 2000. Sounding Out the City. Berg, Oxford. Cerulo, Karen, 1984. Social Disruption and its effects on music an empirical analysis. Social Forces 62 (4), 880894. Citron, Marcia, 1993. Gender and the Musical Canon. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

220

T. DeNora / Poetics 32 (2004) 211221

DeNora, Tia, 1986. How is extra-musical meaning possible? Music as a space and place for work. Sociological Theory 4, 8494. DeNora, Tia, 1995. Beethoven and the Construction of Genius: Musical Politics in Vienna, 17921803. University of California Press, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London. DeNora, Tia, 1997. The Biology Lessons of Opera Buffa. In: Hunter, Mary, Webster, James (Eds.), Opera Buffa in Mozarts Vienna. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 146164. DeNora, Tia, 2000. Music in Everyday Life. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. DeNora, Tia, 2002. Music into action: performing gender on the Viennese concert stage, 17901810. Poetics 30, 1933. DeNora, Tia, Embodiment and opportunity: bodily capital, gender and reputation in Beethovens Vienna. In: Weber, E. (Ed.), The Musician as Entrepreneur. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, (forthcoming). DiMaggio, Paul, 1982. Cultural entrepreneurship in nineteenth-century Boston: the creation of an organizational base for high culture in America, Parts 1 and 2. Media, Culture and Society 4 (3550), 303322. Elias, Norbert, 1993. Mozart: Portrait of a Genius. Polity, Cambridge. Ellis, Katherine, 1997. Female pianists and their male critics in nineteenth-century Paris. Journal of the American Musicological Society 50 (2/3), 353385. Eyerman, Ron, Jamieson, Andrew, 1998. Music and Social Movements. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Fauquet, Joel Marie, Hennion, Antoine, 2000. La grandeur de Bach. Fayard, Paris. Frith, Simon, 1990, Afterthoughts. In: Frith, S., Goodwin, A. (Eds.), On Record: Pop, Rock and the Written Word. Routledge, London, pp. 418424. Giddens, Anthony, 1991. Modernity and Self-identity. Polity Press, Cambridge. Gomart, Emilie, Antoine Hennion, 1999. A sociology of attachment: music amateurs, drug users. In: Law, J., Hazzard, J. (Eds.), Actor Network Theory and After. Blackwells, Oxford, pp. 220247. Green, Lucy, 1997. Music, Gender, Education. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Hennion, Antoine, 1995. The history of art lessons in mediation. Reseaux: the French Journal of Communication 3 (2), 233262. Hennion, Antoine, Fauquet, J.M., 2001. Authority as performance: the love of Bach in nineteenth-century France. Poetics 29 (2), 7588. Johnson, James, 1995. Listening in Paris. University of California Press, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London. Kramer, Lawrence, 2003. Subjectivity rampant! music, hermeneutics, and history. In: Clayton, M., Herbert, T., Middleton, R. (Eds.), The Cultural Study of Music: a Critical Introduction. Routledge, London, pp. 124135. Latour, Bruno, 1987. Science in Action. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA. Leppert, R., 1999. Cultural Contradiction, idolatry, and the piano virtuoso: Franz Liszt. In: Parakilas, J. (Ed.), Piano Roles: Three Hundred Years of Life with the Piano. Yale University Press, New Haven. Leppert, Richard, McClary, Susan (Eds.), 1987. Music and Society. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Martin, Peter, 1995. Sounds and Society: Themes in the Sociology of Music. Manchester University Press, Manchester. Peterson, Richard, A., 1979. Revitalizing the culture concept. Annual Review of Sociology 8, 137166. Peterson, Richard, A., Berger, David, 1990 [1975]. Cycles in symbol production: the case of popular music. In: Frith, S., Goodwin, A. (Eds.), On Record: Rock, Pop and the Written Word. Routledge, London. Pinch, Trevor, Trocco, Frank, 2002. Analog Days: the Invention and Impact of the Moog Synthesizer. Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA. Randel, Donald. 1992. The canon in the musicological toolbox. In: Bergeson, K., Bohlman, P. (Eds.), Disciplining Music: Musicology and its Canons. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp. 1023. Roy, William, 2003. Who shall not be moved?. Folk music, community and race in the American Communist Party and the Highlander School. In: Proceedings of the Sociology of Culture Session on Politics, Strategy and Culture, American Sociological Association Meetings, Atlanta, (August). Roscigno, Vincent, J., Danaher, William F. 2003. The Voice of Southern Labor: Radio, Music and Textile Strikes, 19291934. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis. Russell, D., 1987. Popular Music in England 18401914: a Social History. Manchester University Press, Manchester. Stomatov, Peter, 2002. Interpretive activism and the political uses of Verdis Opera in the 1840s. American Sociological Review 67 (June), 345366.

T. DeNora / Poetics 32 (2004) 211221

221

Weber, William, 1975. Music and the Middle Class. Holmes and Meyer, New York. Wheelock, G. 1993. Schwarze Gredel and the engendered minor mode in Mozarts operas. In: Solie, R. (Ed.), Musicology and Difference: Gender and Sexuality in Music Scholarship. University of California Press, Berkeley, pp. 201224. Tia DeNora teaches sociology at Exeter University (UK). Her most recent book is After Adorno: Rethinking Music Sociology (Cambridge, 2003). Her current research projects focus on music and health care and on the connections between music, material culture, science and social science in 19th century Europe.

You might also like

- A Complete History of Music for Schools, Clubs, and Private ReadingFrom EverandA Complete History of Music for Schools, Clubs, and Private ReadingNo ratings yet

- 1 The Austrian C-Major Tradition: Haydn Symphony 20 Opening - mp3 Haydn Symphony 48 Opening - mp3Document27 pages1 The Austrian C-Major Tradition: Haydn Symphony 20 Opening - mp3 Haydn Symphony 48 Opening - mp3laura riosNo ratings yet

- Gesture As Communication The Art of Carl PDFDocument206 pagesGesture As Communication The Art of Carl PDFLouisSharpéNo ratings yet

- Miriam Hyde Viva VoceDocument1 pageMiriam Hyde Viva VoceLucia SpaninksNo ratings yet

- Beethoven and The MetronomeDocument27 pagesBeethoven and The MetronomeJoe JewellNo ratings yet

- Ottorino Respighi's Pines of Rome tone poem analyzedDocument4 pagesOttorino Respighi's Pines of Rome tone poem analyzedDaniel Huang100% (1)

- Cryptography Using Musical Ideas and SymbolsDocument11 pagesCryptography Using Musical Ideas and Symbolsedition58100% (1)

- Vinteuil PDFDocument7 pagesVinteuil PDFBalotă Ioana-Roxana100% (1)

- Early Music - V31nº2 - MAYO - 2003Document160 pagesEarly Music - V31nº2 - MAYO - 2003Au Rora100% (1)

- Romantic Music Is A Stylistic Movement In: BackgroundDocument6 pagesRomantic Music Is A Stylistic Movement In: BackgroundMixyNo ratings yet

- The Magnificent Mess That Is Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto NoDocument4 pagesThe Magnificent Mess That Is Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto NoJoeNo ratings yet

- Orchestration in Bartok's Concerto For OrchestraDocument4 pagesOrchestration in Bartok's Concerto For OrchestraMichel FoucaultNo ratings yet

- Brahms Piano MusicDocument6 pagesBrahms Piano MusicAksel BasaranNo ratings yet

- Joseph Haydn's 'Clock' Symphony As Representative of His 'London' Symphonic StyleDocument9 pagesJoseph Haydn's 'Clock' Symphony As Representative of His 'London' Symphonic StyleJosh BurnsNo ratings yet

- Grove - BernsteinDocument19 pagesGrove - BernsteinFionn LaiNo ratings yet

- Beethoven FactsDocument7 pagesBeethoven FactsAliyah SandersNo ratings yet

- Concepts of Elements of Sonata TheoryDocument107 pagesConcepts of Elements of Sonata TheoryRobert Morris100% (1)

- Schenker The Decline of The Art of CompositionDocument91 pagesSchenker The Decline of The Art of CompositionMarta FloresNo ratings yet

- Bartok Lendvai and The Principles of Proportional AnalysisDocument27 pagesBartok Lendvai and The Principles of Proportional AnalysisDyrdNo ratings yet

- Preface: by Gennadi Moyseyevich Tsipin Translated Beatrice FrankDocument16 pagesPreface: by Gennadi Moyseyevich Tsipin Translated Beatrice FrankAmy HuynhNo ratings yet

- Studentthesis-Yuanpu Chiao 2012Document468 pagesStudentthesis-Yuanpu Chiao 2012ashujaku69No ratings yet

- Zaslaw - When Is An Orchestra Not An OrchestraDocument14 pagesZaslaw - When Is An Orchestra Not An OrchestraRodrigo Balaguer100% (1)

- Come Unto Jesus PDFDocument4 pagesCome Unto Jesus PDFGabriel Andres Rodriguez ZuluagaNo ratings yet

- Maurice Ravel: French Composer Known for Neo-Classicism and Orchestral WorksDocument2 pagesMaurice Ravel: French Composer Known for Neo-Classicism and Orchestral WorksIreh KimNo ratings yet

- 19th C Opera - Wagnerian - RevolutionDocument24 pages19th C Opera - Wagnerian - RevolutionDorian VoineaNo ratings yet

- Early Musical Term "OrganumDocument2 pagesEarly Musical Term "OrganumOğuz ÖzNo ratings yet

- Ralph Vaughan WilliamsDocument3 pagesRalph Vaughan WilliamsDavid RubioNo ratings yet

- Ashgate IntroDocument9 pagesAshgate Introhockey66patNo ratings yet

- Overview of Western Musical HistoryDocument18 pagesOverview of Western Musical HistoryBrian Williams100% (1)

- Oxford Music Online - Música Programática - Poema Sinfónico - Música AbsolutaDocument22 pagesOxford Music Online - Música Programática - Poema Sinfónico - Música AbsolutaalvinmvdNo ratings yet

- Symphonie Fantastique (Fifth Movement) AnalysisDocument10 pagesSymphonie Fantastique (Fifth Movement) Analysissmooth writerNo ratings yet

- Modal Counterpoint (Palestrina Style) : Metric StructureDocument8 pagesModal Counterpoint (Palestrina Style) : Metric Structuretanislas100% (1)

- Chopin's "Tristesse"Document5 pagesChopin's "Tristesse"Christina KuritsuNo ratings yet

- Richard Wagner's LeitmotifsDocument10 pagesRichard Wagner's LeitmotifsjaysonmichealNo ratings yet

- FLEISHER, The Inner ListeningDocument10 pagesFLEISHER, The Inner ListeningryampolschiNo ratings yet

- Dallas Symphony Presents Peter and the WolfDocument47 pagesDallas Symphony Presents Peter and the WolfThiago AraújoNo ratings yet

- Ludwig Van Beethoven PresentationDocument37 pagesLudwig Van Beethoven PresentationANARICHNo ratings yet

- Ernest ChaussonDocument2 pagesErnest ChaussonRachel SinghNo ratings yet

- Music History AssignmentsDocument3 pagesMusic History AssignmentsJosephNo ratings yet

- (E-Book) Czerny - Lettere Sull'Arte Di Suonare Il PianoforteDocument16 pages(E-Book) Czerny - Lettere Sull'Arte Di Suonare Il PianoforteStefano SintoniNo ratings yet

- Mozarts Tempo Indications Helmut B PDFDocument18 pagesMozarts Tempo Indications Helmut B PDFJuan Casasbellas100% (1)

- Music of The Romantic Era PDFDocument7 pagesMusic of The Romantic Era PDFQuynh NguyenNo ratings yet

- Beethoven Symphony No. 5 Analysis of Mvts II-IVDocument11 pagesBeethoven Symphony No. 5 Analysis of Mvts II-IVTheory of Music100% (2)

- Charles IvesDocument103 pagesCharles IvesJean Marcio SouzaNo ratings yet

- Counterpoint Rules for Standard and Strict StylesDocument2 pagesCounterpoint Rules for Standard and Strict StylessuriyaprakashNo ratings yet

- NICOLAS MEDTNER, THE COMPOSER AND HIS MUSICDocument7 pagesNICOLAS MEDTNER, THE COMPOSER AND HIS MUSICgalltywenallt100% (1)

- Ten PiecesDocument12 pagesTen PiecesSergio Bono Felix100% (1)

- Fugue 1 Book 1Document3 pagesFugue 1 Book 1Anonymous lwY8qpUBUN100% (1)

- An Annotated Catalogue of The Major Piano Works of Sergei RachmanDocument91 pagesAn Annotated Catalogue of The Major Piano Works of Sergei RachmanjohnbrownbagNo ratings yet

- Analysis Haydn 85 MinuetDocument16 pagesAnalysis Haydn 85 MinuetLucas Isaias Di BenedettoNo ratings yet

- Mozart's Symphony No. 41 in C Major (College Essay)Document9 pagesMozart's Symphony No. 41 in C Major (College Essay)GreigRoselliNo ratings yet

- Baroque Reflections in Ludus Tonalis by Paul Hindemith PDFDocument6 pagesBaroque Reflections in Ludus Tonalis by Paul Hindemith PDFapolo9348100% (1)

- Beethoven and C.CzernyDocument55 pagesBeethoven and C.CzernyLuis MongeNo ratings yet

- GUERRA, Paula (2015) - REVIEW Andy Bennett (2013), Music, Style, and Aging - Growing Old DisgracefullyDocument4 pagesGUERRA, Paula (2015) - REVIEW Andy Bennett (2013), Music, Style, and Aging - Growing Old DisgracefullylukdisxitNo ratings yet

- Underground Music Scenes and DIY CulturesDocument1 pageUnderground Music Scenes and DIY Cultureslukdisxit100% (1)

- Advanced Seminar - Call For Application PDFDocument4 pagesAdvanced Seminar - Call For Application PDFlukdisxitNo ratings yet

- HUDSON, Ray (2006) - Regions and Place - Music, Identity and Place PDFDocument10 pagesHUDSON, Ray (2006) - Regions and Place - Music, Identity and Place PDFlukdisxit100% (1)

- Philip Tagg - Analysing Popular Music (Popular Music, 1982)Document22 pagesPhilip Tagg - Analysing Popular Music (Popular Music, 1982)Diego E. SuárezNo ratings yet

- Sara Cohen (1991) - Rock Culture in Liverpool - IntroDocument31 pagesSara Cohen (1991) - Rock Culture in Liverpool - IntrolukdisxitNo ratings yet

- REGEV, Motti (2007) - Ethno-National Pop-Rock Music - Aesthetic Cosmopolitanism Made From Within PDFDocument27 pagesREGEV, Motti (2007) - Ethno-National Pop-Rock Music - Aesthetic Cosmopolitanism Made From Within PDFlukdisxitNo ratings yet

- PETERSON, Richard (1990) - Why 1955 Explaining The Advent of Rock Music PDFDocument21 pagesPETERSON, Richard (1990) - Why 1955 Explaining The Advent of Rock Music PDFlukdisxitNo ratings yet

- REGEV, Motti (2007) - Cultural Uniqueness and Aesthetic Cosmopolitanism PDFDocument17 pagesREGEV, Motti (2007) - Cultural Uniqueness and Aesthetic Cosmopolitanism PDFlukdisxitNo ratings yet

- FORNÄS, Johan (1995) - The Future of Rock - Discourses That Struggle To Define A Genre PDFDocument29 pagesFORNÄS, Johan (1995) - The Future of Rock - Discourses That Struggle To Define A Genre PDFlukdisxitNo ratings yet

- BLUM, Alan - Scenes PDFDocument29 pagesBLUM, Alan - Scenes PDFlukdisxitNo ratings yet

- STRAW, Will - Scenes and Sensibilities PDFDocument13 pagesSTRAW, Will - Scenes and Sensibilities PDFlukdisxitNo ratings yet

- WEINSTEIN, Deena (1991) - The Sociology of Rock - An Indisciplined Discipline PDFDocument14 pagesWEINSTEIN, Deena (1991) - The Sociology of Rock - An Indisciplined Discipline PDFlukdisxit100% (1)

- CRANE, Diana - The Production of Culture (Cap.8) PDFDocument12 pagesCRANE, Diana - The Production of Culture (Cap.8) PDFlukdisxitNo ratings yet

- BENNETT, Andy - Consolidating Music Scenes Perspective PDFDocument12 pagesBENNETT, Andy - Consolidating Music Scenes Perspective PDFlukdisxitNo ratings yet

- BENNETT, Andy (2002) - Music, Media and Urban Mythscapes - A Study of The Canterbury Sound PDFDocument14 pagesBENNETT, Andy (2002) - Music, Media and Urban Mythscapes - A Study of The Canterbury Sound PDFlukdisxitNo ratings yet

- JENSEN, Sune Qvotrup - Rethinking Subculture Capital PDFDocument21 pagesJENSEN, Sune Qvotrup - Rethinking Subculture Capital PDFlukdisxitNo ratings yet

- CRANE, Diana - Culture Worlds - From Urban Worlds To Global Worlds PDFDocument14 pagesCRANE, Diana - Culture Worlds - From Urban Worlds To Global Worlds PDFlukdisxitNo ratings yet

- ERRICKSON, April (1999) - A Detailed Journey Into The Punk Subculture PDFDocument33 pagesERRICKSON, April (1999) - A Detailed Journey Into The Punk Subculture PDFlukdisxitNo ratings yet

- HUDSON, Ray (2006) - Regions and Place - Music, Identity and Place PDFDocument10 pagesHUDSON, Ray (2006) - Regions and Place - Music, Identity and Place PDFlukdisxit100% (1)

- FRITH, Simon (1986) - Art Versus Technology - The Strange Case of Popular Music PDFDocument18 pagesFRITH, Simon (1986) - Art Versus Technology - The Strange Case of Popular Music PDFlukdisxit100% (1)

- BENNETT, Andy (2008) - Towards A Cultural Sociology of Popular Music PDFDocument15 pagesBENNETT, Andy (2008) - Towards A Cultural Sociology of Popular Music PDFlukdisxitNo ratings yet

- Queen We Are The Champions Listening and Vocab Wor Activities With Music Songs Nursery Rhymes 4526Document2 pagesQueen We Are The Champions Listening and Vocab Wor Activities With Music Songs Nursery Rhymes 4526Katia LeliakhNo ratings yet

- Testing of Wireless Radio EquipmentDocument12 pagesTesting of Wireless Radio EquipmentfarrukhmohammedNo ratings yet

- Nissan Sentra N16 Brake Service Manual PDFDocument102 pagesNissan Sentra N16 Brake Service Manual PDFmirage0706No ratings yet

- Kami Export - 22 I Hear American Singing 22 Document 1Document2 pagesKami Export - 22 I Hear American Singing 22 Document 1api-448637771No ratings yet

- Songs in Tonic SolfaDocument35 pagesSongs in Tonic Solfachidi_orji_391% (65)

- GasAlertMicroClip - QRG (D5867 2 EN)Document19 pagesGasAlertMicroClip - QRG (D5867 2 EN)GMNo ratings yet

- Technical Specification ALLGAIER - Laparascopy For GYNDocument6 pagesTechnical Specification ALLGAIER - Laparascopy For GYNJimmyNo ratings yet

- List of Set ClassesDocument2 pagesList of Set ClassesAnonymous zzPvaL89fGNo ratings yet

- ModelbjtDocument19 pagesModelbjtSuraj KamyaNo ratings yet

- PSY286 Answers 6Document5 pagesPSY286 Answers 6Cesar LunaNo ratings yet

- Freedomland (Piano)Document3 pagesFreedomland (Piano)Tiago100% (5)

- Reflection and Refraction, Snell's LawDocument5 pagesReflection and Refraction, Snell's LawMödii PrinzNo ratings yet

- AcrossTheUniverse TheBeatlesDocument1 pageAcrossTheUniverse TheBeatlesarthurcleeNo ratings yet

- SOLiD Technical NoteDocument24 pagesSOLiD Technical NoteJhon GrandezNo ratings yet

- Utlevel IIDocument51 pagesUtlevel IIAruchamy Selvakumar100% (1)

- Bought Me A Cat 3-FormalDocument2 pagesBought Me A Cat 3-Formalapi-250631266No ratings yet

- La Llorona 2vn & Va Score For UploadDocument3 pagesLa Llorona 2vn & Va Score For UploadJulia McKenzieNo ratings yet

- Đề KTHK I -TA 10 -ma de 303 doneDocument3 pagesĐề KTHK I -TA 10 -ma de 303 doneDương VũNo ratings yet

- Grooves Lesson Plan - Announced 2 - 3Document6 pagesGrooves Lesson Plan - Announced 2 - 3api-491759586No ratings yet

- Wideband Guitar PickupsDocument6 pagesWideband Guitar PickupsDeaferrantNo ratings yet

- Scania Radio Premium ManualDocument83 pagesScania Radio Premium ManualAlex Renne ChambiNo ratings yet

- Sony VPL Cs7 SpecsDocument2 pagesSony VPL Cs7 SpecsBombacı MülayimNo ratings yet

- Asia Link Arts 2010Document2 pagesAsia Link Arts 2010Rebecca HolbornNo ratings yet

- 73 Magazine - June 1978Document224 pages73 Magazine - June 1978Benjamin DoverNo ratings yet

- 2011 Schilke Mouthpiece CatalogDocument24 pages2011 Schilke Mouthpiece CatalogchesslyfeNo ratings yet

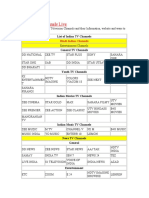

- List of Indian TV Channels and InformationDocument12 pagesList of Indian TV Channels and Informationpace1987No ratings yet

- Carlie McGuire 2017 ResumeDocument1 pageCarlie McGuire 2017 ResumecarliemcguireNo ratings yet

- Retirement Letter of ResignationDocument7 pagesRetirement Letter of ResignationAshuNo ratings yet

- LG 42px4rva PDFDocument37 pagesLG 42px4rva PDFadolfoc261No ratings yet

- In Christ Alone Guitar Key of DDocument1 pageIn Christ Alone Guitar Key of Dfemi augustineNo ratings yet