Professional Documents

Culture Documents

URC - 2005 - The Case of The Teduray People in Eight Barangays of Upi, Maguindanao

Uploaded by

IP DevOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

URC - 2005 - The Case of The Teduray People in Eight Barangays of Upi, Maguindanao

Uploaded by

IP DevCopyright:

Available Formats

Notre Dame University

. Gity

Research Monograph No. 27 J j i

.. - ,I

The Case of the Teduray Peo.,le

In eight barangays of

Upl, Magulndanao

This Research Monograph Series presents the

researches conducted by the University Research Center,

Notre Da111.e UIIiversity, Cotabato City

The University Research Center

has three service units: Socio-Economic Research Center (SERC);

Institutional Research and Development ORD); and DataBank (DB).

With its multi-service units, the University Research Center

performs the NDU Vision-Mission to serve" .. .as a center for the

meeting and dialogue between science and faith". URC's mandate

is to promote the advancement of knowledge and development in

Central Mindanao and the ARMM areas through relevant and multi

disciplinary approaches on issues of change and development of

peoples in this part of Mindanao.

Sln( ~ SOClo-EcONOMIC RESEARCH CENTER

engages in collaboration/participatory action

researches on issues of development local and national. of private and

public agencies/institutions in Region XII (Central Mindanao) and the

Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) areas identified in

the East Asean Growth Area (EAGA) polygon.

INS1"ITUTIONAL RESEARCH

AND DEVEL-OPMENT IRO

serves as the research and planning arm of the University,

providing assistance to University sectors. It conducts institutional

researches and planning development programs for institutional

development.

DATABANK

DB

~ provides collection of facts and figures about strategic

regions of Mindanae, particularly the Autonomous Region in Muslim

Mindanao (ARMM), Region XII (Central Mindanao) and SPCPD areas.

It allows information access and retrieval through Internet-based

system with the 'Federico Aquino Internet of Notre Dame University.

http://www.nduJapenetorg/urcdb/

Socio-Economic Research Center May 2005

I

: 1 ' 1

Research Monograph No. 27

I I . .

The ~ a s e of the Teduray People

In eight barangeys of

Upi, Magulndanao

A research conducted by the NDU Research Center (NDURC) in cooperation

with Accion Contra EI Hambre (ACH)

INTRODUCTION

In physical appearance, the T eduray [he looks of the

Malay. T edurays are traditionally engaged in slash-and

burn farming and practiced animistic form of religion.

They have their own language which is structurally related

to the Malayo-Polynesian family (Schlegel, 1994). Their

traditional clolhing is "bahag" or G-string but is rarely used

this time except for ceremonial or ritual purposes.

According to their attachment to traditional practices,

Teduray may be classified into acculturated and traditional.

The former are those who live in the northernmost portions

of the territory, and who have dose contact with the

lowland settlers, while the latter are those who have

survived deep in the tropical forest region of the Cotabato

cordillera and have retained a traditional mode of

production and value system (de Leon, 2002).

Almost all barangays occupied by the T eduray are hilly and

roiling with limited. scanered plains. The common IlloJe of

transportation in going to the T eduray communities is a

four-wheel drive and double-tire vehicle that could traverse

the rough and rugged terrain. Internal transportation

modes are sine:le motor vehicles, locally known as "skv-Iah".

'-J / / .

and horses. Many of the T eduray depend primarily on

agciculture-based economy with rice and corn as the main

crops. Rain-fed rice and corn farming is the most common

practice in the area. The T eduray thriving in such a

subsistence economy suggests their highly vulnerable

character. Being part of t..h.e mainstream culture, the

farming T edurays have now become fully integrated into

the market economy. Anthropologist Schlegel sees an

intensification of the trend of acculturation of the T eduray

. peoples and considers this tradsformation as

inevitable and irreversible.

Accion Contra El Hambre (ACH) is an non

government organization that addresses hunger, disease,

and other crises that threaten the lives of helpless men,

women, and children. Its program interventions in the

areas of water and sanitation, health, nutrition, and food

security aim to benefit to marginalized and vulnerable

communities. For its program services in this area of

Central Mindanao, it becomes necessary for the ACH to

understand the forms of vulnerability and capacity of the

communities they serve such as those ofTedurays.

It is in this light that Accion Contra El Hambre launched

.I-.F M; i"1I1' lI'a'" \11111 ner , .},; 1

1

-t-v Pro;err Th'"

'-A.......... .L ...... .. V 't Il"A. A&. ... uv...... '-J Uo.) L yu."" LJ .&. J L "

project aimed to facilitate the implementation of more

effective and cost efficient programs that could have better

impact on the local communities. Guided by this principle,

data generation through the Mindanao Vulnerability

Observatory became imperative.

OBJECTIVES AND METHODOLOGY

The MVO is a tool for data generation aimed to

understand the local context of the T eduray community

and to examine the community's vulnerability and risks.

More specifically, it sought to:

1. describe the characteristics of the T eduray

communi ty and households;

1 2

2. determine the nrCilS of vulnerability among the

Tcdnrays and the factors chat explain their

vulnerability; and

3. determine their capnclLJes and COpIng

mechanisms to address their

The study employed both the quantitative and qualitative

techniques of data collection. The quantitative data were

collected from the household survey and community profile

assessment. Secondary data and facts and figures on health,

education, water and sanitation, agricultural production on

rice and corn, income, and other related socio-economic

variables were collected from relevant agencies such as

Department of Health, Region XlI; Department of

Agriculture XlI; Bureau of Agricultural Statistics

Maguindanao, ARMM; National Statistical Coordination

Board XII; National Statistics Office - ARMM; and

Department of Education XII.

TEDURAY COMMUNITY AND LIFEWAYS

Topography and Community

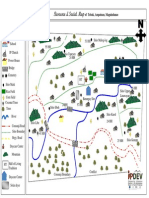

Teduray home is in the municipality of Upi. Upi is

located in the southwestern coast of Maguindanao

province. It is typically mountainous, with scattered hills

and very limited plains. It has also a coastal portion on the

west side facing the vast waters of Illana Bay and Celebes

Sea. It is home to the T eduray people, of the major

I Upi should be taken contextually as homeland ofthe Teduray. Thus, it refers

collectively to the municipalities of Upi referring to the northern halfand

South Upi where the Tedurays predominate in number.

3

ethnolinguistic groups scattered all over Mindanao. These

people are also called highlanders on account of the

physical environment they inhabit. This study covered a

total of 8 barangays, 6 in North Upi (Renede, Rifao, Kiga,

Nalkan, Kibukay and Tambak) and 2 in South Upi

(Pandan and Kuya).

There are also a number of rivers, creeks, lakes, and springs

crisscrossing their homeland. These bodies of water serve

as important sources of water for drinking as well as for

domestic uses. Moreover, among the upland dwellers

where fish is a rarity, these waterways are a boon because of

the fish that abound in them. Water coming from these

sources is also used to irrigate their land.

i

The eight barangays considered in this study recorded an

aggregate population of 23,730 comprising a LOlal of 5,010

households based on the Participatory Rapid Appraisal

(PRA) conducted in 2002. Of these households, the

majority is the Teduray, accounting for 87 percent.

Christian households constitute 9 percent .of the total while

Maguindanaons

constitute 4 percent. Table 1. Percentage Distribution of Households

Table 1 presents the

population composition

of the eight study

barangays.

The eight study

covered about

25,62S hectares. The

ratio of household to

4

land area is 1:5 hectares. There: is one household found

within five hectares of land. ()11 the average, 626 people

inhabited a barangay, indicaring its sparse population.

Taking the 2003 household that involved 119

Teduray households as reference, each household is

estimated to comprise an average of 6 members. This

figure was arrived at based on the total of 716 members

that make up the 119 households covered by the survey.

The male members predominate in number as they make

up 54 percent of the total. Household population is

typically young considering that those who are within the

age range of 0 - 14 years make up (he biggest number

which is 54.37 percent of the total.

Social Organization

Traditionally Teduray commUnIties were organized in

settlements of five to ten families that consrituted dispersed

hamlets, spread out over an area. However presently many

of the T eduray families are living in more concentrated

settlements in the barangays where they are present,

although some of those traditional dispersed hamlets can. be

found as well in inner zones. The basic residential unit is a

nu<;;lear family, composed of father, mother, and the

children. In some cases, unmarried and dependent elders

would form part of the household. The T eduray word for

family is kemureng, which means "pot", that is, a family is

deemed as a group of persons livirig together and earing

from the same pot.

Four overlapping social groups may be identified among

T eduray: the neighborhood, the settlement, the

5

'household, and the nuclear family. The family is

determined by kin ties, the household and settlement are

spatially established, and the neighborhood is a function of

ongoing social ties related to cooperation in day-to-day

subsistence work (Schlegel 1979:6).

Every swidden farmer must associate his family with others

in a neighborhood to be part of the needed cooperative

work group, but he need not live in company of other

families in a settlement. In general, any family is free to

its residence in any settlement it wishes, but very

often, some relationships, either consanguineal or affinal,

link the families that settle together in the same hamlet.

Much sharing goes on among the households of a

settlement. The meat of '.Alild pig 0 1' dtet, or fisll ca.ught in

the river is shared through the entire neighborhood. This

symbolizes the cooperative unity among the members of

the community.

The largest social unit is the inged (neighborhood), which

usually comprises several settlements. The householps

belonging to the inged render mutual assistance among

themselves in all swidden-related activities as well as in all

community rituals. Ordinarily, almost all members of the

inged are linked to one another either by blood or through

marrIage ties.

Socialization for the children starts at an early age. They

are suckled by their mothers up to the age of two or three,

or as long as no new baby has arrived. Bur once .they are

able to walk, they are allowed to play around thevillagc,

without any supervision from the elders. When they reach

the age of six they become helpers in the swidden fields. In

6

working, the Teduray children learn all there is to know

about surviving in their society, so rhat by the time they are

adolescents they do the same work as thei r parents and have

absorbed the skills they need to fun(.oon as Tcduray adults

(Schlegel 1970:21).

Courtship and Marriage

As he turns 16, the Teduray boy's parents and his paternal

grandparents look for a bride in a nearby community.

When they find one, they arrange and make preparations

for the wedding. They thrust a spear thrust in front of the

house of the girl symbolizing that they will be asking for

her hand.

Only in eighth weeks' time will the boy find himself

married. Four weeks after the hand of the girl has been

asked, the dowry for the bride is set, and after another four

weeks, the wedding is celebrated. The wedding, the

r 1 1 1 tIl' 1 :" ,..

preparatIOn or Wnlcn IS aone Dj' tne Dnce-elect s relatives, is

held in the house of the bride-to-be and is officiated by the

oldest member of the group. The hride and the groom

meet for the first time on their wedding day.

In search of a bride, the boy's folks have in mind these basic

considerations: She must (a) be beautiful; (b) possess a

sterfing character; (c) belong to the same social level as the

groom-to-be; (d) be industrious and a good cook; and (e)

be kind to all her in-Jaws and to her husband-to-be.

Inrermarriage is unacceptable to the Teduray; hence,

whoever marries a non-T eduray is banished from the tribe.

Although a girl may have a lover before she gets married,

she is expected to practice faithfulness once she is married.

The T eduray tie procreation to marriage and try to regulate

extra-marital sex not because they want to put sex

per se, but because they are concerned with social stability

and an enduring relationship for childbearing.

Religious Beliefs

The T eduray believe in the existence of gods and spirits for

which they put up altars and shrines. They ask Cadnan or

Tutus, their supreme god, for blessings, while they ask lesser

gods and goddesses for favors: Menowu- T uduk, the god of

forest and mountains for gold; Menowu- Wayeg, goddesss of

fishing and streams and Nabi, the god of sea and sea-life ,for

fish; Cadnan, the Almighty, and the gods of four directions

Tegenon (North), Sibangan (East), Dtidiggan (South):

Fledl)11. ('X'est) t')r safe trayel ; and Tftzki, the , angel 9f

goodwill and Kukum, the god of justice for justice. The

Beliyan (religious leader) naked except for a loincloth prays

for favors through his songs and q,ances. The Tedur,ay

believe that heaven is for them and hell is ,for the non

Teduray.

Rituals.

As the T eduray forage for food, they perform a ritual,

either the betel nut offering or the burning of incense. In

the betel nut offering, the betel nut is placed on top of

bamboo stakes, either in front of one's house or on the

field of palay or corn that one wishes to be' blessed. The

Beliyan or the old woman prays aloud . the

betel nut offering. In the burning of incense, the same

method is used as in the betel nut offedng, ,except that

instead of the betel nut, incense or duka is burned. The

Beliyan prays first before doing either of the rituals.

__________________ ,8 7

Livelihood.

for a long time. the T eduray practiced a suhsistence system

mainly based on traditional swidden agriculture.

Supplemental food supplies were procured rhrough hunting

and fishing. Other necessities of life. such as iron tools for

slash and burn agriculture. were obtained through trade

with the Maguindanaon. Cotton material only came in

through trade activities since weaving was unknown to the

T eduray. These articles were obtained by exchanging their

rattan, almaciga, beeswax. and tobacco.

The T eduray who have turned to plow farming have been

integrated into the cash, credit, and market economy to

follow agricultural techniques and crop selection entailed

by a peasant type of economic production. Majority of

them are small land cultivators.

Since ancient times, the Teduray have been known as

skillful hunters and trappers. Aside from their skili at

setting traps and snares, T eduray hunters are experts in

using the blowgun. the bow and arrow, and the homemade

shotgun.

In recent years, the classification of T eduray society into the

traditional and acculturated has been most pronounced in

the differentiation of their subsistence systems. Schlegel, an

anthropologist who has done intensive studies on dle

Teduray, saw this in the two settlements he observed: Figel

and Kakaba-kaba. Schlegel describes Figel as a system

adapted to the tropical rainforest, consisting of slash and

;burn andshifling cultivation. It is augmented by hunting,

fishing, and food-gathering activities and only marginally

dependent on trading wi th the coastal economy. Kakaba

kaba is described as consisting of plow farming in areas that

have virtually lost the old forest cover. It is no longer

dependent on forest resources; instead, it is involved

extensively with the market economy of a rural, lowland

society (Schlegel, 1979: 164).

Schlegel, in his studies among the T eduray, has determined

that trade relations existed between the T eduray and the

Maguindanaon in fairly recent times. Prior to the coming

of the American rule, the Maguindanaon were seldom

allowed to penetrate the hill country of the T eduray. This

was partly because the Maguindanaon were known to be

slave takers, and partly because the T eduray were in general

suspicious of people of different customs other than their

own. The only exception to this was in the case of certain

ritually approved rraders and peddlers.

The trade that went on between rhe Teduray and the

Maguindanaon was essential to both parties. From the,

Maguindanao'n the T eduray got their cloth for clothing,

iron tools for swidden agriculture, salt, and the various

goods used by the T eduray for brideprice and legal

settlements: krises, necklaces, brass boxes, gongs, spears,

and the like. In return, the Maguindauaon gOi their rattan,

tobacco, bees wax, almaciga (Agathis philippinensis Warb),

and gutta percha (sap of the tree which the T eduray call

tefedus (Palaquium ahernanum Merr).

The livelihood activities of the Teduray are made distinct

by the type of topography they are situated in. Most of the

households are engaged in farming activities apparently

because population is concentrated in the highlands. Those

residing in the coastal barangays of Nalkan, T ambak, and

part of Rifao have fishing as the major source of livelihood.

___________________________________ 10 .

9

----------------------------------

Corn is the dominant crop raised. Upland and lowland

rice farming are likewise engaged in by some of the

residents although the annual volume of production is

typically held at the minimum. Other crops raised include

coffee, mongo, peanuts, vegetables, cassava, and other

perennials like fruit trees.

t

Teduray Inged

1

The political organization of the T eduray society IS not

hierarchical but rather fundamentally egalitarian. Each

inged of subsistence groups may have a leader who sees to

the clearing of the swidden, the planting and harvesting of

crops, and the equal sharing of the rice or any other food

produced from the land. The leader or head also

determines, in consultation with the shaman (beliyan) when

10 move next and clear another swidden settlement.

T eduray society is governed and kept together by their adat

or custom law, and by an indigenous legal and justice

system designed to uphold the adat. As an acknowledged

expert in custom law, a kefeduwan exercises the legal and

moral authority. The expert presides over the tiyawan, the

formal adjudicatory discussion before which is brought

cases involving members of the community for deliberation

and settlement.

i

The kefeduwan sposition is not based on wealth. It is not a

separate position or profession, because he continues to

carry on the usual economic activities of the other menfolk

in the community. The one who is most learned in

I

T eduray customs and laws, possessing a skill in reasoning, a

remarkable memory, and an aptitude for calmness in

debate, and who learns to speak in the highly metaphorical

rl

11

rhetoric of a tiyawan is apt to be acknowledged as a

kefeduwan. It is possible for one inged to have more than

one kefeduwan.

: : J

The main responsibility of a kefeduwan in T eduray society

is to see to il that the respective rights and the feelings of all

the people involved in the case up for settlement are

respected and satisfied.

Among the acculturated T eduray, the role of the traditional

legal authority is almost entirely diminished, and peasant

Teduray are constituents of the normal representatives of

municipal Philippine law and politics, mostly non-Teduray.

The second major leader of traditional T eduray sociely is

t..h.c shaman (belryan). This person may either be a man or a

woman, who has the gift from the spirit world of being able

to see and talk to spirits. He or she has a special kind of

legal authority to settle disputes between spirits and

humans. Aside from his or her healing functions, the

shaman is also the ritual leader at a series of communal

sacred meals (kandulz) which are observed by traditional

T eduray four times each year, marking off significant

points in the swidden cycle. The kanduli is a powerful

ritual statement of the interdependence and cooperation

which exists between neighbor and neighbor, and berw.een

humans and spirits in all aspects of life. .

Among acculturated peasant Teduray, the role of the

shaman, like that of the traditional authority, has greatly

decreased through the transformation of the subsistence

system and the general acceptance of Christianity. In 1926,

the Philippine Episcopal Church was invited by Capt.

Edwards to do extensive missionary work among the

12

Teduray. After the Second World War, the Roman

Catholic Church and other Protestant denominations

entered Teduray areas. As a result, many Teduray families

took on Christianity as a part of their new peasant Filipino

way of life. They adopted the Western manner of dressing,

began using the national language, and sent their children

to public and parochial schools. Various government and

religious-sponsored clinics have been established and are

used by many of the acculturated Teduray, although belief

in the spirits rather than germs as the cause of disease

remains strong and folk healers continue to play a major

role among the T eduray as they do among many rural

Filipinos.

Most T eduray view the profound changes their society is

undergoing with certain sadness, and with a deep sense of

pride in the culture of their forebears. But according to

Schlegel (1994), the transformation of their way of life

seems inevitable and irreversible now. As the older

religious and iegai authorities fade from importance, their

place is being taken over by a new set of educated leaders

Teduray lawyers, school tcachers, government officials,

agricultural experts, and the like. It is these people who

will lead the T eduray as they dravI ever farther away from

their traditional forest isolation and into the new ways,

l

r

opportunities, and challenges of participation in the

mainstream of Philippine life.

LF L- , .

o

s

Ancestral Domain Claim rADC).

The barangays covered in the study are in an area claimed

t '"' I th 'T' 1 M c 11 . C

as Ancestral l.)omam oy e 1 euutay. lallY. 11 not al , 01

the Tedurays share the sentiment expressed in one of the .

FGD:

" ... (Our) ancestral domain claim is important to us

because this is the way we can reclaim the land

14

13

----------------------------------------------

owned by ancestors ... Our ancestors gave it to us

but because of poverty, we mortgaged it in order

for us to eat. Many are not able to redeem these

mortgages as they have no money to pay for it.

Odlers left and stayed with relatives in other

places". (MVO- FGD Feb 2004)

Presently Teduray communmes are coordinating with

T eduray leaders who know the process of the claim though,

as far as they know, there is no clear process and

implementation of the Ancestral Domain Claim. The

administrative competencies under which they have to

submit their daim belong to ARMM, which has not

implemented the procedure contemplated under the

Indigenous Peoples' Right Act (IPRA, 1997) and still has to

define its own legislation about Indigenous Peoples and

Ancestral Domain Claims. They also recognize that a

major problem with ancestral domain claim is boundary

conflicts and the presence of other ethnic communities that

migrated several decades ago in their lands.

ISSUES AND CHALLENGES

Like most other indigenous tribes in the country, Teduray

present a high exposure to vulnerability factors, derived

mainly from their geographical isolation, loss of traditional

soy.rces of subsistence, loss of cultural identity and

marginality of the mainstrearn society. The causes and

manifestations of their vulnerability have multiplied

profoundly over the years. The T eduray strongly oppose

the . loss of natural resources and biodiversity due to

environmental degradation through their political struggle

to have access and control over lands that they consider as

their Ancestral Domain which were used by T eduray

communities since immemorial time. , They are also

fighting for the recognition of their traditional government

practices and way of life.

1. Loss of natural resources and biodiversity.

The T eduray' s dependence on swidden farming indicates

the subsistence economy of its people. Relying heavily on

production from rainfed agriculture, the T eduray suffer low

productivity from their corn and rice crops. For

generations, the slash and burn practice in upland farming

contributed much to the destruction of their land resource

resulting in poorer productivity and income.

In addition, the forest reserves in their topography attracted

the logging concessionaires of the region. Many

mountainous and hilly barangays, primarily barangay Rifao,

have been exposed to iilegal logging activities stripping

them of their once thick and lush forest resources. Armed

groups of the concessionaires caused peace and order

problems in the community as they attempted to quell the

rpc-;s""nrp "f ..he

.I.,"-, .u LU .... '-.;\.- v. L .U " .I. \.....U. l Iny \/11 1. 1 .... . . .l. J\"'c,n1!!5

The local residents oppose loggers because they know that

deforestation will have adverse effect on them because it

will lead to soil erosion and the depletion of soil fertility

that will [utlher aggravate the poor productivity of their

farms. During heavy rains, many barangays are prone to

flash floods. In such times, the Teduray suffer not only

from poor harvest but from displacement as well.

Environmental degradation has adversely affected their

fishing resources also, which has traditionally been art

important complementary source of food and income for

many T eduray families. . l'eduray fishing com m uni ties ,

noted the decreasing variety and volume of the fish

available in their coastlines, springs and rivers. The fishing

waters have become polluted and have greatly diminished

15 16

the fishing communities' fish catches for food consumption

and family income.

2. Loss of cultural identity

Through generations, the influx of logging conce:ssion(lires

and the construction of basic infrastructures such as roads

and bridges facilitated the coming of peoples and

technology from the dominant society. As more roads and

bridges were built, people of different cultures came lured

by the community's resources. The T eduray were

introduced to new farm practices, farm implements and

equipment, and prevailing farm technoEogy. Traditional

customs and practices were slowly modified through their

imeracrions with other cultural groups such as Visayan

settlers (Ilongos, Cebuanos... ) and Muslim settlers

(Maguindanaon), coming to their communities. Their

Iifeways , language, clothing and

spared from the cultural infl

jntenningling of the tribes.

food patterns were

uences caused by

not

the

3. Famine.

The Teduray's low farm production has been compounded

by the increasing impact of the logging activities to their

farms. Their physical resources continue to deteriorate as a

result ,of flash floods and soil erosion. The T eduray are

exposed as well to long periods of drought that make them

vulnerable to food scarcity. Upland families suffer the most

risk of famine, as the dry season gives them poor harvest

and even prevents them from engaging in vegetable and

livestock raising activities. They have very limited access to

farm inputs that would have enabled them to make their

land productive. Other forms of livelihood are likewise

hard to come by; consequently, they resort to borrowing

food or money to buy food for the family. At times, when

borrowing is not available, families resort to hunting and

collecting wild crops and fruits, but as years go by they have

become more and more scarce and sometimes they may

not be suitable for food consumption.

4. Illness and Death.

Several factors such as unbalanced nutrition and diet, poor

housing condition, unsafe water sources, and poor

sanitation make them susceptible to diseases and illnesses. A

high prevalence of contagious diseases like diarrhea,

malaria, and slcin diseases affect many T eduray, both young

and old.

The T eduray also registered high mortality among infants

and the under-five children group. They have very low

access to medical health professionals orner than the basic

medical health services in the barangay heath station, which

at most times, runs short of medicines and health

eqUIpment.

5. Loweduc..liun leveL

Many adult members of T eduray households in the study

area are illiterate or have low level of education/no formal

schooling. This characteristic makes them more vulnerable

to social and economic injustices imposed by external forces

(owners of productive resources) present in their

communities. It also hinders their capacity to Lranslate the

non-human resources such as land and other materials into

outputs that contribute to the local economy. This low

level of literacy among the T eduray in the survey areas is

further aggravated by the inadequacy of educational

facilities and services needed to develop their productive

skills.

17 18

----------------------------------------------

6. Other hazards.

Displacements either due to natural of man-made

calamities are potential hazards to the T eduray. The

possibility of flash floods during the rainy season and the

long drought during t..h.e dry season are rish that

T eduray are always exposed to.

In addition, the intermittent peace and order problem and

lawlessness in the T eduray community owing to the

logging issue continues to bring anxiety to the upland

families. The functionality of their traditional T eduray

Justice and Governance in resolving Teduray conflicts is a

source of comfort and protection in the community.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The recommendations made here are offered to alleviate

the vulnerabilities of the T eduray as a community.

Strategies that require community, government, and private

sectors' intervention to respond more systematically and

eff(::ctively to the plight of this marginalized and vulnerable

tribe deserve serious consideration.

1. Access and control to lands

The local government agency (DAR/MARO) could help

the T eduray people through the implementation of

Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program, particularly on

the issuance of the Certificate of Land Occupancy

Agreement (CLOA) if there is a need! to improve the land

tenure condition among the T eduray households who are

share tenants and settlement cultivators.

Another instrument that will increase access and control of

lands among the T eduray people is the implementation of

the Indigenous Peoples Rights Act (IPRA), which aims at

protecting the lives and heritage and advancing the interest

of the indigenous peoples in the Philippines. The issuance

of a Certificate of Ancestral Domain Claim (CADC)/

Certificate of Ancestral Domain Title (CADn will ensure

access and control among the Teduray people over their

ancestral domain. This piece of document will give them

the power to decide on the utilization of their lands. The

official recognition of their lands would eventually expedite

the Delivery of agriculrural services/support &om the

government and private sector.

Increased access to land and the introduction of programs

on appropriate farm technology may eventually improve

the farm practices among T eduray farmers.

Comprehensive agricultural support from Department of

Agriculture may be sourced out for this purpose.

The loss of natural resources and biodiversity may be

reversed through reforestation and the preservation of the

",-" rem'lining

.&,\"J

f"rp

1

.-he

l.I' aiL,.,.

_ .!!.t5 ___

l..e

t.!.!. ... .a. ... u. .......... .L....... '-'JL..'l

:n

I. rt-tL'- '_J.!..!

proper techniques of cultivating rolling/hilly lands can

prevent soil erosion. The Department of Environment and

Natural Resources (DENR) can extend assistance to this

concern.

Coastal marine resources need to be assessed so that

necessary intervention can be introduced. A participatory

approach may be employed in order to involve the fisher

folks in the protection of coastal resources.

2. Education Program

The low iiteracy ievel and formal! education level among the

T eduray in the study areas is primarily due to the lack of

appropriate education services in their barangays, worsened .

by their distance from the urban centers and to their

19 20

economic poverty. A package of educational programs that

will address specific needs of different sectors of the

community (such as: day care centers below five (5) years

old children, elementary/secondary education, vocational

and technical education for the young adults,' and

ftmctional literacy progra...rn for adults) may be developed

and implemented for the empowerment of Teduray people.

Non-government organizations or Academic Institutions

may consider any of these programs as part of their

extension programs or functional literacy programs.

Preservation of T eduray culture may be included in the

curriculum/program. This will help revive and enrich the

indigenous tradition and practices especially among the

T eduray youth.

3. Program

To address the health needs of children, mothers, and

women in the area, there is a need to imroduce training

programs for health workers in the community. A well

designed training program that will address issues on

malnutrition, importance of immunization, birth delivery

and childbearing, and childcare is imperative.

TraditionaJ healing practices must be a component of the

health program. The promotion of herbal gardens in every

backyard will help to ' address the households' health

problems that could be treated . by herbal medicine.

Training for Traditional Healers and Traditional Birth

Attendants can contribute to improve their practices.

4: Water and Sanitation

There is a need (0 address the problem on the water sources

of the people in the area. There are springs and open wells

that need to be developed irito sources of potable water.

Sanitary toilets are also needed in the area. The education

of the people on proper environmental sanitation and

hygiene practices should be included as component of any

program in this field.

5. Community Organization and Participation

Organization of farmers, youth and women in the

barangays is important to the empowerment of the

community with respect to addressing their specific needs.

This will also help them to protect their interest as a

people. There is a need to introduce activities that will help

enhance their collective bargaining with external forces

affecting the marketing of their products. Alternative

sources of livelihood like backyard gardening may be

introduced through organized groups of families.

Partnership among stakeholders - GOs and NGOs and the

community people must be forged so that proper synergy

among them may be achieved. This can be done through

conduct of orientations, trainings and other similar

ac

:-;,l !t!F, Thp,F i, <::.), a ;-,-, c: -" .:; l--.lich t'li' __ . ___ _. _._ ___ v ..

networking and delineation of functions among partners.

6. Peace programs

There is need to organize a peace and development councii

that will be instrumental in the conduct of training and

advocacy for the promotion of a culture of peace. A

T raining Program for the council members may also be

designed for this purpose. Through this program the

Council membersllocal leaders will be equipped

app '"t" A. ..1. .......... ........

.1. . &.

rnnri'1t-r'

_

knnu,ledge

..I.", "y &.

sl,.;I1

...'-1..1. .....

...

,

'In

... 1.1. I y",o.."",-.1.

,.,,,'>nrc ;n

I

their own communiry. Any Peace Program should integrate

the Teduray Traditional Governance and Justice System

that is used by T eduray in dealing with and resolving their

conflicts. Seminars and workshops with government

officials should be held in order to make them aware of

22 21

traditional practices of T eduray on settling their conflicts

and for them to identify mechanisms to integrate these

practices as alternative/complementary t() the Philippine

judicial system.

7. Monitoring and evaluation

A system of monitoring and evaluation must be defined at

the barangay council levels at the outset of any intervention

that will be introduced in the Teduray communities.

Community people must be involved in all the steps of the

project cycle, from the initial identification and definition

of the intervention and its implementation, to tlle

monitoring and evaluation phase in order to promote their

feeling of ownership. Community involvement will help

ensure better impact and facilitate the future sustainability

of (he interventions.

;

The Final Report of this research abstr<K:t is available at the University Research Center.

23

The University Center

has three service units: Sofio-I';c'CIIIUllli('

Institutional Researcll ali(I \)cwdOIlIll ClJll (lJ.(U); ullel l)utnBulII<. (\)B).

With its multi-service IIl1il.s, Uw (11I 1VC'I'slly

performs the NDU Visioll-Mission 1.0 .....111'1 II ('('1111'1' 1'01'

meeting and iIIul I'uilll". IlI<C'N

is to promote the of I<.lIuwh'clI-:CllIlICl (\c'VC'I"pllwlIl III

Central Mindanao Hncll.h(l t\I<MM I 111'0111-: 11

disciplinary 011 issll ns of C'l1I1I1"W anll clpwlulIlIWIlt. of

peoples in this pm'!. of Mirulall:Jo,

SI!IC( &. SOClo-ECONOMIC RESEARCH CENTER

(lIq..IYCS III (OIl.lbor.,tlon/pdrtlc IpalolY .1C Uon

researches on issues of dcwlopmcnllocall .1Od n."lonal, of prlvt'lll' MId

public agencies/institutions ill R<'Hlon XII ((('nth,1 Mlnd.mt'lo) ,1Od the

Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindal'hlO (ARMM) .ura,. Idl' nUnrd In

the East Asean Growth Area (EAGA) polycJol1,

INSTITUTIONAL RESEARCH

AND DEVELOPMENT

I

o

serves as the rcse.m h .lnd pl,1I1nlnq arm or the LJnlvfrslty,

providing assistance to Unive,,,lly ",do,." It (onducts Intututlonal

researcl:les and plcmninq dewlopm,' nl progr,'Rl S "or Institutiona l

development.

0

'8" DATABANK

provides wll cdlon oll.)(t...md nqur

regions of Mind.1I1cIO, ptlrllculclrly thl' Autonomous Reqlon In Muslim

Mindanao (ARMM), Region XII (CrnlriJl Mlnd.1ni1o) and SPePO areas.

It allows inforllMtion (l(((,ss dnd rl'lrlrval through Intrrnet-based

system with the 'federico Aquino Internet or N

http://www.nduJap('nctorg/urcdb/

Notre/Dame Unive"fsity

, Cotabato :tity

Research Monograph No, 27 . i - .. ..

The Case of the Teduray People

"

In eight barangays of

Upl, Magulndanao.

This Research Monograph Series presents the

researches conducted by the University Research CenteL;

Notre Dame UniversifJ; Cotabato City

You might also like

- Bending The WorldDocument25 pagesBending The WorldMallory Young100% (2)

- BatanesDocument2 pagesBatanesNivra Lyn EmpialesNo ratings yet

- Armenians in IndiaDocument46 pagesArmenians in IndiaMaitreyee1No ratings yet

- BODONG in The Province of Abra 1325746412Document20 pagesBODONG in The Province of Abra 1325746412Jayson Basiag100% (3)

- Critical Analysis of Who Can Be A Trustee and Beneficiary of A Trust Under Indian Trust Act 1882Document47 pagesCritical Analysis of Who Can Be A Trustee and Beneficiary of A Trust Under Indian Trust Act 1882kavitha50% (2)

- Be Filled With The SpiritDocument8 pagesBe Filled With The SpiritJhedz CartasNo ratings yet

- 10 Oldest Churches in The PhilippinesDocument10 pages10 Oldest Churches in The PhilippinesJowan Macabenta100% (3)

- PRIESTLY REPERTOIREDocument70 pagesPRIESTLY REPERTOIRE789No ratings yet

- The Union of Indian PhilosophiesDocument10 pagesThe Union of Indian PhilosophiesSivasonNo ratings yet

- Tiruray Ethnic Group of PhilippinesDocument3 pagesTiruray Ethnic Group of PhilippinesChuzell Lasam67% (3)

- List of Licensed and Accredited Social Welfare Agencies in the PhilippinesDocument324 pagesList of Licensed and Accredited Social Welfare Agencies in the PhilippinesNorlynne MercolesNo ratings yet

- History of PilarDocument20 pagesHistory of PilarEredao Magallon CelNo ratings yet

- Navadvipa Bhava TarangaDocument18 pagesNavadvipa Bhava TarangaJoshua BrunerNo ratings yet

- Ethnic Groups in The Philippines - 20231004 - 152917 - 0000Document97 pagesEthnic Groups in The Philippines - 20231004 - 152917 - 0000Mampusti MarlojaykeNo ratings yet

- (Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies) Iftekhar Iqbal-The Bengal Delta - Ecology, State and Social Change, 1840-1943-Palgrave Macmillan (2010) PDFDocument289 pages(Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies) Iftekhar Iqbal-The Bengal Delta - Ecology, State and Social Change, 1840-1943-Palgrave Macmillan (2010) PDFmongalsmitaNo ratings yet

- MANSAKA, TERURAY, TBOLI, HIGAONON AND SUBANON TRIBESDocument6 pagesMANSAKA, TERURAY, TBOLI, HIGAONON AND SUBANON TRIBESjs cyberzoneNo ratings yet

- Caraballo TribeDocument1 pageCaraballo TribeArlene PalasicoNo ratings yet

- Customary LawsDocument3 pagesCustomary LawsReymel EspiñaNo ratings yet

- Hanapbuhay at Relihiyon NG Mga TausugDocument4 pagesHanapbuhay at Relihiyon NG Mga TausugAntoinette Genevieve LopezNo ratings yet

- Mandaya: Etymology and Geographic LocationDocument2 pagesMandaya: Etymology and Geographic Locationannabel immaculataNo ratings yet

- I. Profile: Calaoan Ancestral DomainDocument29 pagesI. Profile: Calaoan Ancestral DomainIndomitable RakoNo ratings yet

- IrayaDocument2 pagesIrayaapi-26570979100% (1)

- The Ati & Tumandok People of Panay IslandDocument14 pagesThe Ati & Tumandok People of Panay IslandAngie MandeoyaNo ratings yet

- The Kalibugan Subanen: A Mixed Culture in the PhilippinesDocument14 pagesThe Kalibugan Subanen: A Mixed Culture in the PhilippinesJacinth May BalhinonNo ratings yet

- TirurayDocument3 pagesTirurayPatrisha Marie Iya Bautista67% (3)

- T'boli Tribe of South Cotobato - Cultural Traits and RitualsDocument2 pagesT'boli Tribe of South Cotobato - Cultural Traits and RitualsAnonymous PlatypusNo ratings yet

- 5.4 Type of Social Org - MaganiDocument4 pages5.4 Type of Social Org - MaganiJim D L BanasanNo ratings yet

- HistoryDocument5 pagesHistoryGrizell CostañosNo ratings yet

- The MamanwaDocument5 pagesThe MamanwaKlent Adrian DagsaNo ratings yet

- Housekeeping 1 (Guestroom Cleaning) Module Materials List of ModulesDocument10 pagesHousekeeping 1 (Guestroom Cleaning) Module Materials List of ModulesNikki Jean HonaNo ratings yet

- IPs REPORTDocument11 pagesIPs REPORTMae Dela PenaNo ratings yet

- FuppppDocument9 pagesFuppppJacinth May Balhinon50% (2)

- LIT ReportDocument60 pagesLIT ReportDanmar Arteta100% (1)

- Roots of Philippine Indigenous Cultural CommunitiesDocument73 pagesRoots of Philippine Indigenous Cultural CommunitiesRodolfo CampoNo ratings yet

- Review of NGO Roles in Indigenous Community DevelopmentDocument6 pagesReview of NGO Roles in Indigenous Community DevelopmentKaryl Mae Bustamante OtazaNo ratings yet

- The Mandaya People of MindanaoDocument7 pagesThe Mandaya People of MindanaoKhristian Joshua G. JuradoNo ratings yet

- Ilonggo Birth TraditionsDocument5 pagesIlonggo Birth Traditionsgodwinkent888No ratings yet

- History of AntiqueDocument4 pagesHistory of AntiqueELSA ARBRENo ratings yet

- Mountain ProvinceDocument2 pagesMountain Provincesaint mary jane pinoNo ratings yet

- History of Balut Island RevealedDocument17 pagesHistory of Balut Island RevealedJessemar Solante Jaron WaoNo ratings yet

- Barangay Pallocan West: Batangas CityDocument26 pagesBarangay Pallocan West: Batangas CityAlbain LeiNo ratings yet

- From Deen BenguetDocument17 pagesFrom Deen BenguetInnah Agito-RamosNo ratings yet

- Chapter - Viii - Preactivity - Ical, Erica Ann e PDFDocument5 pagesChapter - Viii - Preactivity - Ical, Erica Ann e PDFErica Ann IcalNo ratings yet

- History of Talakag municipality in the PhilippinesDocument1 pageHistory of Talakag municipality in the PhilippinesJuliet OrigenesNo ratings yet

- Filipino and Filipino Culture in The Eyes of Rizal and MorgaDocument16 pagesFilipino and Filipino Culture in The Eyes of Rizal and MorgaJOAN KYLA CASTROVERDENo ratings yet

- NSTP-CWTS Areas of Concern for Burauen CommunityDocument2 pagesNSTP-CWTS Areas of Concern for Burauen CommunityIan Conan JuanicoNo ratings yet

- PE3 AssessmentDocument2 pagesPE3 AssessmentBangtan is my LIFENo ratings yet

- Articles About RizalDocument22 pagesArticles About RizalJoie LovenNo ratings yet

- A Brief History of The Town of BulanDocument3 pagesA Brief History of The Town of BulanmotmagNo ratings yet

- Tribal Burial Traditions in Mindanao - Philippine CultureDocument3 pagesTribal Burial Traditions in Mindanao - Philippine CultureMidsy De la CruzNo ratings yet

- Manobo Tribe: BY: Micutuan, Dolly Mae Montza, NeljenDocument8 pagesManobo Tribe: BY: Micutuan, Dolly Mae Montza, NeljenRegine Estrada JulianNo ratings yet

- Mamanwa-WPS OfficeDocument5 pagesMamanwa-WPS OfficeScaireNo ratings yet

- Ifugao Heritage NotesDocument11 pagesIfugao Heritage Notesdel143masNo ratings yet

- The Ati of Negros and PanayDocument4 pagesThe Ati of Negros and PanayAngie MandeoyaNo ratings yet

- Group Activity - Sustainable - Mangyans of MindoroDocument14 pagesGroup Activity - Sustainable - Mangyans of MindoroK CastleNo ratings yet

- Region 9Document26 pagesRegion 9Jeane DagatanNo ratings yet

- Vision, Mission, Goals, and Philiosophy of PupDocument1 pageVision, Mission, Goals, and Philiosophy of PupJemilyn Cervantes-SegundoNo ratings yet

- Final Report of Ata-Manobo DavaoDocument74 pagesFinal Report of Ata-Manobo DavaoJyrhelle Laye SalacNo ratings yet

- The endangered Isarog Agta tribe of the PhilippinesDocument2 pagesThe endangered Isarog Agta tribe of the Philippinesvan jeromeNo ratings yet

- History of TirurayDocument3 pagesHistory of TirurayStandin Kemier100% (1)

- Culture in Mindanao 2023 Chapter1Document21 pagesCulture in Mindanao 2023 Chapter1Johaina AliNo ratings yet

- 1 Self-AnthropologyDocument20 pages1 Self-AnthropologyLaarni Mae Suficiencia LindoNo ratings yet

- Topic 2 - The Philippine Indigenous Cultural Communities (Luzon)Document31 pagesTopic 2 - The Philippine Indigenous Cultural Communities (Luzon)PeepowBelisarioNo ratings yet

- Visayas Ethnic GroupDocument4 pagesVisayas Ethnic GroupLandhel Galinato LoboNo ratings yet

- Culture of The Philippines Indigenous TribeDocument12 pagesCulture of The Philippines Indigenous TribeKate strange0% (1)

- Understanding Culture, Society, and PoliticsDocument13 pagesUnderstanding Culture, Society, and PoliticsRenjun HuangNo ratings yet

- Reference Project - ENGDocument25 pagesReference Project - ENGprakash sheltonNo ratings yet

- Community Organizing Participatory Action Research: Prepared byDocument69 pagesCommunity Organizing Participatory Action Research: Prepared byJanaica JuanNo ratings yet

- Promoting Environmental Education Among The Indigenous Tribes in Occidental Mindoro Through 4Ps: Public-Private-People-PartnershipDocument14 pagesPromoting Environmental Education Among The Indigenous Tribes in Occidental Mindoro Through 4Ps: Public-Private-People-PartnershipMary Yole Apple DeclaroNo ratings yet

- Ketindeg 4Document11 pagesKetindeg 4IP Dev100% (1)

- Ketindeg 2-3Document15 pagesKetindeg 2-3IP DevNo ratings yet

- Ketindeg 10 (Final Issue)Document56 pagesKetindeg 10 (Final Issue)IP DevNo ratings yet

- Mou Forges Armm-Ipdev Cooperation: What'S Inside?Document12 pagesMou Forges Armm-Ipdev Cooperation: What'S Inside?IP DevNo ratings yet

- DepEd Guidelines On The Conduct of Activities and Use of Materials Involving Aspects of Indigenous CultureDocument11 pagesDepEd Guidelines On The Conduct of Activities and Use of Materials Involving Aspects of Indigenous CultureIP DevNo ratings yet

- Implications of BBL Provisions On The Environment, Peace & Devt WorkDocument24 pagesImplications of BBL Provisions On The Environment, Peace & Devt WorkIP DevNo ratings yet

- Resource Map - Bgy TubakDocument1 pageResource Map - Bgy TubakIP DevNo ratings yet

- Program (Decommissioning)Document1 pageProgram (Decommissioning)IP Dev100% (1)

- The Evolution of The Center of Teduray GovernanceDocument2 pagesThe Evolution of The Center of Teduray GovernanceIP DevNo ratings yet

- Indigenous Ritual For PeaceDocument2 pagesIndigenous Ritual For PeaceIP DevNo ratings yet

- The Struggle of ParaTech Joel JurimochaDocument10 pagesThe Struggle of ParaTech Joel JurimochaIP DevNo ratings yet

- The Evolution of The Center of Teduray GovernanceDocument2 pagesThe Evolution of The Center of Teduray GovernanceIP DevNo ratings yet

- BBL AlternativeProvisionsDocument3 pagesBBL AlternativeProvisionsIP DevNo ratings yet

- FADRHO - Conflict-Affected Fusaka Inged PDFDocument9 pagesFADRHO - Conflict-Affected Fusaka Inged PDFIP DevNo ratings yet

- Thesis RA 8713Document25 pagesThesis RA 8713Mike23456No ratings yet

- FADRHO - Conflict-Affected Fusaka Inged PDFDocument9 pagesFADRHO - Conflict-Affected Fusaka Inged PDFIP DevNo ratings yet

- Ubo Brief HistoryDocument15 pagesUbo Brief HistoryIP Dev100% (8)

- POSITION PAPER - Full Inclusion of The Indigenous People's in The Bangsamoro PDFDocument7 pagesPOSITION PAPER - Full Inclusion of The Indigenous People's in The Bangsamoro PDFMatet NorbeNo ratings yet

- 1st IP Cultural Festival Proposed Program FlowDocument1 page1st IP Cultural Festival Proposed Program FlowIP DevNo ratings yet

- Program Flow (Detailed)Document2 pagesProgram Flow (Detailed)IP DevNo ratings yet

- World IP Day 2013 - Statement of Support-IPDEVDocument2 pagesWorld IP Day 2013 - Statement of Support-IPDEVIP DevNo ratings yet

- BBL Provisions Relevant To The Indigenous PeoplesDocument30 pagesBBL Provisions Relevant To The Indigenous PeoplesIP Dev100% (1)

- Program Flow RTD On The Promotion and Protection of IP Child and Maternal Health CareDocument1 pageProgram Flow RTD On The Promotion and Protection of IP Child and Maternal Health CareIP DevNo ratings yet

- Invitation To EveryoneDocument1 pageInvitation To EveryoneIP Dev100% (1)

- Ketindeg 9 - Vol 3 Issue 1Document17 pagesKetindeg 9 - Vol 3 Issue 1IP DevNo ratings yet

- LDCI CONCLUDING SEMINAR - Tentative Program, V. 4 Aug, 2014Document2 pagesLDCI CONCLUDING SEMINAR - Tentative Program, V. 4 Aug, 2014IP DevNo ratings yet

- Genealogy TedurayDocument1 pageGenealogy TedurayIP DevNo ratings yet

- Invitation To Congressional Consultation - 26JuneADDUDocument2 pagesInvitation To Congressional Consultation - 26JuneADDUIP DevNo ratings yet

- Program - Congressional Consultations Upi LegDocument2 pagesProgram - Congressional Consultations Upi LegIP DevNo ratings yet

- MOA AFP NCIP - Oct2012Document2 pagesMOA AFP NCIP - Oct2012IP DevNo ratings yet

- CH A Workbook 2019 2020 Semester 1Document155 pagesCH A Workbook 2019 2020 Semester 1avitugNo ratings yet

- Joint Induction and Turnover Ceremonies ScriptDocument7 pagesJoint Induction and Turnover Ceremonies ScriptLarry BarcelonNo ratings yet

- How Much Do You Know About RamadanDocument1 pageHow Much Do You Know About Ramadanmutty254No ratings yet

- Maranatha Singers Double Praise Album TracklistsDocument7 pagesMaranatha Singers Double Praise Album TracklistsEliel RamirezNo ratings yet

- List of Holidays 2017 University of Gour BangaDocument2 pagesList of Holidays 2017 University of Gour BangaSimanta DeNo ratings yet

- Mahakavi Bhasa Father of Indian Drama PDFDocument5 pagesMahakavi Bhasa Father of Indian Drama PDFGm Rajesh29No ratings yet

- Envelope Secretary Job DescriptionDocument2 pagesEnvelope Secretary Job DescriptionsttomsherwoodparkNo ratings yet

- The Bible - The Word of GODDocument5 pagesThe Bible - The Word of GODNard LastimosaNo ratings yet

- Digital Age Challenges for Consecrated LifeDocument3 pagesDigital Age Challenges for Consecrated LifeJennifer GrayNo ratings yet

- Martyr EssayDocument2 pagesMartyr Essayapi-315053317No ratings yet

- Ingeborg Bachman - War DiaryDocument63 pagesIngeborg Bachman - War Diarypatrickezoua225No ratings yet

- Daftar Nilai Semester Genap 20212022Document35 pagesDaftar Nilai Semester Genap 20212022sellaNo ratings yet

- SMV English Meaning Shloka by ShlokaDocument163 pagesSMV English Meaning Shloka by ShlokabhargavimoorthyNo ratings yet

- Byzantine Catholic Church in SlovakiaDocument5 pagesByzantine Catholic Church in SlovakiaŽan MorovićNo ratings yet

- Malaysia National Education PhilosophyDocument25 pagesMalaysia National Education PhilosophyDaniel Koh100% (1)

- Law of Rylands v FletcherDocument14 pagesLaw of Rylands v FletcherMeghesh KhandelwalNo ratings yet

- The Father: Bjørnstjerne BjørnsonDocument5 pagesThe Father: Bjørnstjerne Bjørnsonmae sherisse caayNo ratings yet

- Teori BtaDocument268 pagesTeori BtaNoviaNo ratings yet

- FDN&INT Aut2013 ResultsDocument163 pagesFDN&INT Aut2013 ResultsAsma RehmanNo ratings yet

- Tolstoy RR TheoryDocument5 pagesTolstoy RR TheoryMarny AlcobillaNo ratings yet

- Kamigakari Core Book ErrataDocument351 pagesKamigakari Core Book ErrataCarlos GBNo ratings yet