Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Wall Street Journal Article From Rich Neumeister

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Wall Street Journal Article From Rich Neumeister

Copyright:

Available Formats

Hard to Put Red-Light Violations Under a Lens

By CARL BIALIK

As red-light cameras have proliferated around the U.S. over the past two decades to hundreds of cities and towns, there is one troubling detail: They don't always make traffic intersections safer. Police departments in more than 500 cities and towns use the camerasand, usually, signs warning of their presenceto record motorists who run red lights and to ticket them. The goals are to deter drivers from going through an intersection after the light has turned red and to prevent dangerous crashes. In recent years, municipalities including Los Angeles, Philadelphia and St. Petersburg, Fla., have found that crashes increased at intersections where cameras are installed. Here, a red-light camera in Lawrence Township, N.J., last year. But local results can vary. In recent years, municipalities including Los Angeles, Philadelphia and St. Petersburg, Fla., have found that crashes increased at intersections where cameras are installed. Everything from the choice of intersection, to how long a light stays yellow before turning red, to the methods used to evaluate the cameras can influence whether they are deemed successful. Counting rear-end crashes, for example, can sometimes mean the cameras increase the total number of accidentsas drivers slam on the brakes when they see a warningthough even an overall increase in collisions can be worthwhile, some researchers say, if the most severe crashes decline. "We don't have a laboratory where we can look at these things," said Kimberly Eccles, a principal at Vanasse Hangen Brustlin Inc., an engineering consulting firm. Red-light cameras have been controversial for several reasons. Privacy advocates regard them as intrusive, and many motorists complain they have been unfairly ticketed for relatively minor infractions, such as rolling right turns on red. The conflicting research results on cameras' effectiveness have made them a contentious issue for local authorities, too. Municipalities must strike a balance between using peer-reviewed studies from other towns or citieswhich include advanced statistical analysis and control for traffic volume and other factorsand using their own raw numbers, which may not account for all factors but do reflect local conditions.

"It's sort of a mistake in some ways for every city to try to conduct a comprehensive analysis of a countermeasure"such as red-light cameras"applied on a limited basis, where they don't have the data or, in some cases, the expertise to do the analysis," said Richard Retting, a consultant with Sam Schwartz Engineering in Fairfax, Va. Mr. Retting worked for 20 years for the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, or IIHS, an insurance-industry-funded group, where he published several studies finding safety benefits from red-light cameras. He compares conducting studies of every camera-equipped intersection in a region to doctors conducting individual research papers on each patient rather than relying on published medical studies. But Declan O'Scanlon, a New Jersey state assemblyman, said the state department of transportation's initial study of crashes at camera-equipped intersectionswhich didn't control for traffic volume or other factorswas critical in forming his opinion that cameras "do not reduce accidents, which makes them not worthwhile." The state, in a report published in November, found that crashes in most categories of severity increased at camera-equipped intersections in the year after they were installed. Researchers caution that raw data could mislead in several ways. For one thing, simple counts of crashes lump together rear-end hits that damage cars but not people with more dangerous rightangle crashes. Some studies, such as the New Jersey report, translate types of crash into their typical cost equivalentfor instance, $216,000 for disabling injury compared with $7,400 for crashes that damage only property. Just a few fatal crashes can skew the results because they are assigned a cost value in the millions of dollars. Simple before-and-after comparisons also won't do, researchers say. For one thing, intersections typically are chosen for camera installation because they have had a spate of accidents. That makes them due for a fall just by statistical chance. Also, other traffic trends or enforcement measures, such as speed cameras, could account for changes in crash rates. And choosing another site for comparison isn't easy: Choose one too close to intersections with cameras and it could experience a so-called spillover effect, when camera-less intersections along the same route are affected by motorists conditioned by cameras. Some traffic engineers say other types of interventions can be at least as beneficial as cameras, without their privacy issues. Lengthening yellow-light intervals, for example, gives motorists more time to hit the brakes. Simon Washington, a civil-engineering professor at Queensland University of Technology in Brisbane, Australia, co-wrote a study for the Arizona Department of Transportation in 2005 that cited other work showing that extending yellow-light intervals can reduce red-light running by 50% to 70%. But Prof. Washington isn't sure that is the way to go. "If you increase yellow times all around, you reduce the capacity of intersections," he said.

Extending yellow times could also backfire by causing longer queues at lights and more rear-end crashes as motorists are surprised by the stopped traffic, said Ms. Eccles, the transportationengineering consultant. She added that red-light cameras generally are effective when deployed correctly. However, "because of the controversial nature of red-light cameras, I do believe an agency should consider everything else" before installing them, she said. Learn more about this topic at WSJ.com/NumbersGuy. Email numbersguy@wsj.com. A version of this article appeared February 2, 2013, on page A2 in the U.S. edition of The Wall Street Journal, with the headline: Hard to Put Red-Light Violations Under a Lens.

You might also like

- Research Paper On Red Light CamerasDocument7 pagesResearch Paper On Red Light Camerasguzxwacnd100% (1)

- Numerical Simulation of CrashDocument8 pagesNumerical Simulation of CrashFernando Jose NovaesNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Red Light Cameras in Chicago: An Exploratory AnalysisDocument8 pagesEffectiveness of Red Light Cameras in Chicago: An Exploratory AnalysisScott DavisNo ratings yet

- Brad Lander's Traffic Safety PlatformDocument6 pagesBrad Lander's Traffic Safety PlatformGersh Kuntzman100% (1)

- HawkeyeRadar 10reasons WhitepaperDocument18 pagesHawkeyeRadar 10reasons WhitepaperCORAL ALONSONo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Red Light Cameras Final Report Rev 11-07-14Document25 pagesEvaluation of Red Light Cameras Final Report Rev 11-07-14Scott FienNo ratings yet

- Red Light Camera Effectiveness EvaluationDocument33 pagesRed Light Camera Effectiveness EvaluationRochester Democrat and ChronicleNo ratings yet

- News 01Document2 pagesNews 01Daniel CorrêaNo ratings yet

- HawkeyeRadar Accuracy-Evolving Whitepaper-1Document17 pagesHawkeyeRadar Accuracy-Evolving Whitepaper-1CORAL ALONSONo ratings yet

- No Drivers Required: Million % StatesDocument2 pagesNo Drivers Required: Million % StatesJordanNo ratings yet

- Thesis Traffic SafetyDocument4 pagesThesis Traffic Safetykatrekahowardatlanta100% (1)

- Autonomous Vehicles - An Issue of TrustDocument3 pagesAutonomous Vehicles - An Issue of TruststormillaNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Autonomous CarsDocument6 pagesResearch Paper On Autonomous Carsnynodok1pup3100% (1)

- AdaptedDocument4 pagesAdaptedapi-511003789No ratings yet

- Vehicular Accident ThesisDocument7 pagesVehicular Accident Thesiskmxrffugg100% (2)

- Literature Review of Road Safety at Traffic Signals and Signalised CrossingsDocument6 pagesLiterature Review of Road Safety at Traffic Signals and Signalised Crossingsgw0gbrweNo ratings yet

- REPORT IipDocument11 pagesREPORT IipShabd PrakashNo ratings yet

- A Review Paper On Development of E-VehiclesDocument6 pagesA Review Paper On Development of E-VehiclesIJRASETPublicationsNo ratings yet

- Transportation Research Part C: Yichuan Peng, Mohamed Abdel-Aty, Qi Shi, Rongjie YuDocument11 pagesTransportation Research Part C: Yichuan Peng, Mohamed Abdel-Aty, Qi Shi, Rongjie YuSajid RazaNo ratings yet

- Sensors: Obstacle Detection and Safely Navigate The Autonomous Vehicle From Unexpected Obstacles On The Driving LaneDocument22 pagesSensors: Obstacle Detection and Safely Navigate The Autonomous Vehicle From Unexpected Obstacles On The Driving Lanetak hiroNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Road Traffic Accident Using Data Mining: KeywordsDocument9 pagesAnalysis of Road Traffic Accident Using Data Mining: Keywordsnidhichandel11No ratings yet

- Texting Raises Crash Risk 23 TimesDocument4 pagesTexting Raises Crash Risk 23 TimesScott NorrisNo ratings yet

- Autonomous Vehicles Are Driving Blind - Julia AngwinDocument3 pagesAutonomous Vehicles Are Driving Blind - Julia Angwinnastynate800No ratings yet

- PPR056Document40 pagesPPR056n_lp01No ratings yet

- Black Spot Analysis Methods Literature ReviewDocument4 pagesBlack Spot Analysis Methods Literature Reviewe9xy1xsv100% (1)

- Traffic Congestion Research PaperDocument6 pagesTraffic Congestion Research Paperc9spy2qz100% (1)

- Article 3Document21 pagesArticle 3sandhyasbfcNo ratings yet

- Literature Review of Traffic Signal DesignDocument8 pagesLiterature Review of Traffic Signal Designc5qrve03100% (2)

- Argument EssayDocument5 pagesArgument Essayapi-550020621No ratings yet

- Visual DistractionDocument22 pagesVisual Distractionchandru1878307No ratings yet

- Distracted Driving Lesson Packet - 2021Document10 pagesDistracted Driving Lesson Packet - 2021Kaitlyn FlippinNo ratings yet

- Accident Analysis and Prevention: Loukas Dimitriou, Katerina Stylianou, Mohamed A. Abdel-AtyDocument15 pagesAccident Analysis and Prevention: Loukas Dimitriou, Katerina Stylianou, Mohamed A. Abdel-AtySajid RazaNo ratings yet

- The Impacts of Electric Cars On Road Safety - Insights From A Realworld Driving StudyDocument11 pagesThe Impacts of Electric Cars On Road Safety - Insights From A Realworld Driving Studybardia.hszdNo ratings yet

- Daytime Preceding Vehicle Brake Light Detection Using Monocular VisionDocument12 pagesDaytime Preceding Vehicle Brake Light Detection Using Monocular VisionPhani NNo ratings yet

- Effects of Traffic Signal CoorDocument14 pagesEffects of Traffic Signal CoorAishah RashedNo ratings yet

- Road Safety Evaluation Using Traffic ConflictsDocument8 pagesRoad Safety Evaluation Using Traffic Conflictsramadan1978No ratings yet

- Applsci 12 02907 v3Document20 pagesApplsci 12 02907 v3AaroncilloNo ratings yet

- Damage Detection and Classification of Road SurfacesDocument9 pagesDamage Detection and Classification of Road SurfacesIJRASETPublicationsNo ratings yet

- Reduction of Ambulance Response Time and Accident Detection Using IP and CPMDocument7 pagesReduction of Ambulance Response Time and Accident Detection Using IP and CPMIJRASETPublicationsNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Traffic SignalsDocument4 pagesLiterature Review On Traffic Signalsaflstquqx100% (1)

- Traffic Light Research PaperDocument4 pagesTraffic Light Research Paperfypikovekef2100% (3)

- Analysis of Braking MarksDocument11 pagesAnalysis of Braking Marksnenad milutinovicNo ratings yet

- Autonomous Cars Research PaperDocument6 pagesAutonomous Cars Research Papernjxkgnwhf100% (1)

- WreckWatch Automatic Traffic Accident Detection AnDocument29 pagesWreckWatch Automatic Traffic Accident Detection AnEmariel LumagbasNo ratings yet

- HojunLee - Black Ice Detection Using CNN For The Prevention of Accidents in Automated VehicleDocument4 pagesHojunLee - Black Ice Detection Using CNN For The Prevention of Accidents in Automated Vehicleseokheehan06No ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0001457518301076 MainDocument10 pages1 s2.0 S0001457518301076 MainRodrigo Guerrero MNo ratings yet

- New Speed Cameras to Improve Road SafetyDocument12 pagesNew Speed Cameras to Improve Road SafetyNzs ReceptionNo ratings yet

- Grant Speed Limit Review - Press ReleaseDocument4 pagesGrant Speed Limit Review - Press ReleaseChristian SwerydaNo ratings yet

- Vehicles Earning Good IIHS Side Ratings Reduce Driver Death Risk by 70Document3 pagesVehicles Earning Good IIHS Side Ratings Reduce Driver Death Risk by 70Pankaj GoyalNo ratings yet

- Effects of Red Light Camera Enforcement On Fatal Crashes in Large US CitiesDocument6 pagesEffects of Red Light Camera Enforcement On Fatal Crashes in Large US Citieswora123pot100% (1)

- CDOT Red Light Camera ProgramDocument6 pagesCDOT Red Light Camera ProgramAlisa HNo ratings yet

- WreckWatch Automatic Traffic Accident Detection AnDocument29 pagesWreckWatch Automatic Traffic Accident Detection AnManikantareddy KotaNo ratings yet

- VideoDocument2 pagesVideosnehadsNo ratings yet

- Silva Et Al. (2020)Document23 pagesSilva Et Al. (2020)Atila MarconcineNo ratings yet

- Safety Evaluation Process for Two-Lane Rural Roads - A 10-Year ReviewDocument25 pagesSafety Evaluation Process for Two-Lane Rural Roads - A 10-Year Reviewramadan1978No ratings yet

- Generalized Parking Occupancy Analysis Based On DiDocument25 pagesGeneralized Parking Occupancy Analysis Based On DiMuchammad DaroWardyNo ratings yet

- Unsupervised traffic accident detection in first-person videosDocument9 pagesUnsupervised traffic accident detection in first-person videosShifana TasneemNo ratings yet

- CTS14 05 PDFDocument26 pagesCTS14 05 PDFSusan BolañosNo ratings yet

- Black Spot Cluster Analysis of Motorcycle AccidentsDocument14 pagesBlack Spot Cluster Analysis of Motorcycle AccidentsDinesh Poudel100% (1)

- 2016 Dibble Thissen Hornstein End-of-Session ReviewDocument5 pages2016 Dibble Thissen Hornstein End-of-Session ReviewMN Senate Transportation & Public Safety Committee & Finance DivisionNo ratings yet

- 2015 Dibble Town Hall FlyerDocument1 page2015 Dibble Town Hall FlyerMN Senate Transportation & Public Safety Committee & Finance DivisionNo ratings yet

- 2014 Dibble Hornstein End of Session ReportDocument5 pages2014 Dibble Hornstein End of Session ReportScott DibbleNo ratings yet

- Letter To Senator Dibble 1.6.2014 (Use of Cellular Exploitation Eqt.)Document6 pagesLetter To Senator Dibble 1.6.2014 (Use of Cellular Exploitation Eqt.)abbysimonsNo ratings yet

- SF 927 Counsel SummaryDocument2 pagesSF 927 Counsel SummaryMN Senate Transportation & Public Safety Committee & Finance DivisionNo ratings yet

- Dibble & Hornstein Letter To Zelle July 18, 2013Document3 pagesDibble & Hornstein Letter To Zelle July 18, 2013MN Senate Transportation & Public Safety Committee & Finance DivisionNo ratings yet

- MnDOT DBE Audit Response Zelle Letter To Dibble & HornsteinDocument10 pagesMnDOT DBE Audit Response Zelle Letter To Dibble & HornsteinMN Senate Transportation & Public Safety Committee & Finance DivisionNo ratings yet

- State Sen. Scott Dibble Letter To Zygi Wolf Regarding The Kluwe Allegations ReportDocument1 pageState Sen. Scott Dibble Letter To Zygi Wolf Regarding The Kluwe Allegations ReportFluenceMediaNo ratings yet

- FAA Letter To Metropolitan Airports CommissionDocument2 pagesFAA Letter To Metropolitan Airports CommissionMN Senate Transportation & Public Safety Committee & Finance DivisionNo ratings yet

- Letter To Commissioner Dohman About Cellular Exploitation Equipment Use by The Department of Public SafetyDocument2 pagesLetter To Commissioner Dohman About Cellular Exploitation Equipment Use by The Department of Public SafetyMN Senate Transportation & Public Safety Committee & Finance DivisionNo ratings yet

- MnDOT DBE Audit May 2013Document21 pagesMnDOT DBE Audit May 2013MN Senate Transportation & Public Safety Committee & Finance DivisionNo ratings yet

- SF 871 Counsel SummaryDocument1 pageSF 871 Counsel SummaryMN Senate Transportation & Public Safety Committee & Finance DivisionNo ratings yet

- B10 Mandate Letter To Senate ChairsDocument2 pagesB10 Mandate Letter To Senate ChairsMN Senate Transportation & Public Safety Committee & Finance DivisionNo ratings yet

- Dibble & Hornstein Letter To Commissioner Zelle About DBE Audit May 2013Document2 pagesDibble & Hornstein Letter To Commissioner Zelle About DBE Audit May 2013MN Senate Transportation & Public Safety Committee & Finance DivisionNo ratings yet

- MnDOT DBE Audit Response Attachments 1-10Document23 pagesMnDOT DBE Audit Response Attachments 1-10MN Senate Transportation & Public Safety Committee & Finance DivisionNo ratings yet

- March 20, 2013 AgendaDocument2 pagesMarch 20, 2013 AgendaMN Senate Transportation & Public Safety Committee & Finance DivisionNo ratings yet

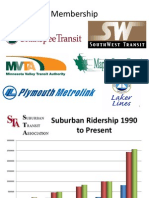

- SF 927 Suburban Transit HandoutDocument3 pagesSF 927 Suburban Transit HandoutMN Senate Transportation & Public Safety Committee & Finance DivisionNo ratings yet

- SF 607 Counsel SummaryDocument2 pagesSF 607 Counsel SummaryMN Senate Transportation & Public Safety Committee & Finance DivisionNo ratings yet

- SF 934 Counsel SummaryDocument2 pagesSF 934 Counsel SummaryMN Senate Transportation & Public Safety Committee & Finance DivisionNo ratings yet

- SF 1173 Counsel SummaryDocument1 pageSF 1173 Counsel SummaryMN Senate Transportation & Public Safety Committee & Finance DivisionNo ratings yet

- SF 607-Street Improvement Fee (Opponents' Handout)Document1 pageSF 607-Street Improvement Fee (Opponents' Handout)MN Senate Transportation & Public Safety Committee & Finance DivisionNo ratings yet

- SF 927 Presentation HandoutDocument13 pagesSF 927 Presentation HandoutMN Senate Transportation & Public Safety Committee & Finance DivisionNo ratings yet

- SF 1133 Counsel SummaryDocument2 pagesSF 1133 Counsel SummaryMN Senate Transportation & Public Safety Committee & Finance DivisionNo ratings yet

- SF 607 2013 Fact SheetDocument2 pagesSF 607 2013 Fact SheetMN Senate Transportation & Public Safety Committee & Finance DivisionNo ratings yet

- March 18, 2013 AgendaDocument1 pageMarch 18, 2013 AgendaMN Senate Transportation & Public Safety Committee & Finance DivisionNo ratings yet

- SF271 PresentationDocument8 pagesSF271 PresentationMN Senate Transportation & Public Safety Committee & Finance DivisionNo ratings yet

- SF 271 Counsel SummaryDocument1 pageSF 271 Counsel SummaryMN Senate Transportation & Public Safety Committee & Finance DivisionNo ratings yet

- SF1133 FiscalNoteDocument2 pagesSF1133 FiscalNoteMN Senate Transportation & Public Safety Committee & Finance DivisionNo ratings yet

- SF 1305 Counsel SummaryDocument1 pageSF 1305 Counsel SummaryMN Senate Transportation & Public Safety Committee & Finance DivisionNo ratings yet

- SF271 Fiscal NoteDocument2 pagesSF271 Fiscal NoteMN Senate Transportation & Public Safety Committee & Finance DivisionNo ratings yet

- ENGLISH COACHING CORNER MATHEMATICS PRE-BOARD EXAMINATIONDocument2 pagesENGLISH COACHING CORNER MATHEMATICS PRE-BOARD EXAMINATIONVaseem QureshiNo ratings yet

- Ceramic Tiles Industry Research ProjectDocument147 pagesCeramic Tiles Industry Research Projectsrp188No ratings yet

- Java Material 1Document84 pagesJava Material 1tvktrueNo ratings yet

- How COVID-19 Affects Corporate Financial Performance and Corporate Valuation in Bangladesh: An Empirical StudyDocument8 pagesHow COVID-19 Affects Corporate Financial Performance and Corporate Valuation in Bangladesh: An Empirical StudyInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Markard Et Al. (2012) PDFDocument13 pagesMarkard Et Al. (2012) PDFgotrektomNo ratings yet

- Grand Central Terminal Mep Handbook 180323Document84 pagesGrand Central Terminal Mep Handbook 180323Pete A100% (1)

- Currency Exchnage FormatDocument1 pageCurrency Exchnage FormatSarvjeet SinghNo ratings yet

- Semi Detailed Lesson Format BEEd 1Document2 pagesSemi Detailed Lesson Format BEEd 1Kristine BuenaventuraNo ratings yet

- Ticket Frankfurt Berlin 3076810836Document2 pagesTicket Frankfurt Berlin 3076810836farzad kohestaniNo ratings yet

- Installation Guide for lemonPOS POS SoftwareDocument4 pagesInstallation Guide for lemonPOS POS SoftwareHenry HubNo ratings yet

- Case Study Series by Afterschoool - The Great Hotels of BikanerDocument24 pagesCase Study Series by Afterschoool - The Great Hotels of BikanerKNOWLEDGE CREATORSNo ratings yet

- wBEC44 (09) With wUIU (09) Technical Manual - v13.03 ENGLISHDocument73 pageswBEC44 (09) With wUIU (09) Technical Manual - v13.03 ENGLISHLee Zack100% (13)

- Soft Matter Physics Seminar on Non-Equilibrium SystemsDocument98 pagesSoft Matter Physics Seminar on Non-Equilibrium Systemsdafer_daniNo ratings yet

- Fa2prob3 1Document3 pagesFa2prob3 1jayNo ratings yet

- Rate of Change: Example 1 Determine All The Points Where The Following Function Is Not ChangingDocument5 pagesRate of Change: Example 1 Determine All The Points Where The Following Function Is Not ChangingKishamarie C. TabadaNo ratings yet

- Fmi Code GuideDocument82 pagesFmi Code GuideNguyễn Văn Hùng100% (4)

- Wheatstone Bridge Circuit and Theory of OperationDocument7 pagesWheatstone Bridge Circuit and Theory of OperationAminullah SharifNo ratings yet

- Examen 03 Aula - F PostgradoDocument5 pagesExamen 03 Aula - F PostgradodiegoNo ratings yet

- Organic FertilizerDocument2 pagesOrganic FertilizerBien Morfe67% (3)

- History of Architecture in Relation To Interior Period Styles and Furniture DesignDocument138 pagesHistory of Architecture in Relation To Interior Period Styles and Furniture DesignHan WuNo ratings yet

- Gas Turbine MaintenanceDocument146 pagesGas Turbine MaintenanceMamoun1969100% (8)

- Catalogo Bombas PedrolloDocument80 pagesCatalogo Bombas PedrolloChesster EscobarNo ratings yet

- Mercado - 10 Fabrikam Investments SolutionDocument3 pagesMercado - 10 Fabrikam Investments SolutionMila MercadoNo ratings yet

- J S S 1 Maths 1st Term E-Note 2017Document39 pagesJ S S 1 Maths 1st Term E-Note 2017preciousNo ratings yet

- 2021.01 - Key-Findings - Green Bond Premium - ENDocument6 pages2021.01 - Key-Findings - Green Bond Premium - ENlypozNo ratings yet

- Adverse Drug Reactions in A ComplementaryDocument8 pagesAdverse Drug Reactions in A Complementaryrr48843No ratings yet

- Teamcenter 10.1 Business Modeler IDE Guide PLM00071 J PDFDocument1,062 pagesTeamcenter 10.1 Business Modeler IDE Guide PLM00071 J PDFcad cad100% (1)

- VNL-Essar Field Trial: Nairobi-KenyaDocument13 pagesVNL-Essar Field Trial: Nairobi-Kenyapoppy tooNo ratings yet

- BSC6900 UMTS Hardware Description (V900R017C10 - 01) (PDF) - enDocument224 pagesBSC6900 UMTS Hardware Description (V900R017C10 - 01) (PDF) - enmike014723050% (2)