Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Tuoba Xianbei and The Northern Wei Dynasty

Uploaded by

cardeguzmanOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Tuoba Xianbei and The Northern Wei Dynasty

Uploaded by

cardeguzmanCopyright:

Available Formats

The Tuoba Xianbei and the Northern Wei Dynasty It is believed that the Tuoba Xianbei (also known

as the Toba Wei and the Tabgatch) developed an independent cultural identity separating them from the larger cultural milieu of Eastern Hu peoples of northern China sometime in the first century BCE. No mention of the Xianbei appears in the annals of Chinese history until later, yet it is the Tuoba Xianbei's own legends have helped to establish an approximate place of origin for this people. The Xianbei creation myth has their earliest ancestors emerging from a sacred cave, the location of which was lost to the Tuoba Xianbei themselves. According to the Weishu, the history of the Northern Wei dynasty later founded by the Tuoba Xianbei, in 443 CE a contingent of horsemen known as the Wuluohou asked for an audience with the Northern Wei emperor Tuoba Dao. They informed him that their people had heard of a cave located in what is now the Elunhchun Autonomous Banner in northeastern Inner Mongolia. The local inhabitants worshiped this cave as a Xianbei ancestral shrine, a fact that convinced Tuoba Dao that the legendary cave that gave birth to his people had been located. The Weishu goes on to say that the emperor sent an emissary, Li Chang, to investigate the report. Li Chang verified the story, and held various ceremonies to worship the Xianbei ancestors, and left an inscription describing the ceremonies. The cave, known today as Gaxian cave site, and the inscription were discovered in 1980 by archaeologists. This find and other historical and archaeological evidence has helped to verify that the Tuoba Xianbei probably emigrated south from this area sometime in the early first century CE. By the mid-third century CE, Xianbei controlled much of northern China, from Hebei and Shanxi to the Daqing Mountains in Inner Mongolia. In 258 a Xianbei confederation was formed, and a few decades later came to the aid of the Western Jin dynasty, who were under attack from an army led by a Liu Yuan, a man of Xiongnu descent who made an unsuccessful bid to reestablish the Xiongnu empire. As a reward, the Western Jin granted the Xianbei leader, Tuoba Yituo, a fiefdom and military rank. This, however, was not enough to put an end to Xiongnu ambitions. They sacked the Western Jin capital in 311 CE and established the brief reign later referred to in Chinese histories as the Former Qin. The Former Qin court forcibly removed the Xianbei to Shandong province, removed their leader to their capital Changan as hostage, took away their herds and stationed troops that forced them to engage in agriculture. By the late 380s the Former Qin dynasty had effectively collapsed after a failed attempt to conquer southern China, and the hostage Xianbei leader, Tuoba Gui, took the opportunity to establish his own reign as King of the State of Wei in 386. In 398, with much of northern China was under his control, Tuoba Gui set up the capital of the Northern Wei empire of Pingcheng (modern Datong in Shaanxi).2 After repeated attacks from

nomadic groups moving south from Outer Mongolia, in 429 the Northern Wei launched a decade-long military campaign, forcing the nomads to submit and effectively securing their northern border. The Northern Wei dynasty proceeded to effectively rule what would become the longest-lived and most powerful of the northern empires prior to the reunification of northern and southern China under the Sui and Tang dynasties. Trade flourished between China and Central Asia, and the influence of Indian artistic styles is particularly evident in the art of the Northern Wei period. Like the Mongols a millennium later, the Xianbei came to rely heavily on Han Chinese administrators and bureaucrats to help run the state. This close contact with Chinese culture helped transform the Xianbei aristocratic class from nomadic horsemen to Sinophilic urbanites. Important and influential families (including the imperial family) adopted Chinese surnames, abandoned traditional dress for Chinese fashions, and perhaps most importantly for Chinese art history, converted to Buddhism, which they enthusiastically patronized. Great wealth and large parcels of land were donated to Buddhist monasteries, which would later lead to a serious drain of capital and a real threat to the state. But for most of the fifth century, Buddhism received the virtually unrestrained support of the Northern Wei court, except during a brief period from 446 to 452, when the emperor Dai Wudi (423-452) made Daoism the religion of state, and brutally persecuted Buddhism and its clergy and monasteries, as well as its art, literature and architecture. Upon Wudi's death, the persecution ended, and generous court sponsorship of Buddhism resumed. The highlight of this sponsorship is arguably the cave temples of Yungang, and the eclectic monumental icons that so clearly demonstrate the Northern Wei sculptural style. While the sinicization of the Northern Wei rulers pleased the empire's Chinese subjects, it alienated those Tuoba Xianbei who desired to retain their ethnic identity. Feeling abandoned by their own rulers in favor of Chinese subjects, compounded by the loss of capital through extravagant patronage of Buddhist culture, led to a military uprising in 524. A few years later, a full civil war exploded after the empress Hu had the emperor Xiao Mingdi assassinated in order to put her son on the throne. Both she and her child were killed in 534, and the empire was split into two halves, ruled by the Eastern and Western Wei dynasties, which would rule only for a number of decades until the establishment of the Sui dynasty in 589.

Period of the Northern and Southern Dynasty (386-589) The period between 386 and 581 A.D. in Chinese history is conventionally called the Northern and Southern Dynasties, when North Chinaunder the control of the Tuoba clan of the Xianbei tribe (a protoMongol people)was politically separated from, yet culturally connected with, the Chinese dynasties established in Jiankang (Nanking). The Northern Wei rulers were ardent supporters of Buddhism, a foreign religion utilized as a theocratic power for ideological and social control of the predominantly Chinese population. In the south, meanwhile, Confucian intellectuals engaged themselves in Neo-Daoist debates on metaphysical subjects, and learned monks studied and propagated Buddhist ideas that were in some ways compatible with Daoist philosophy. The Buddhist rock-cut caves at the site of Yungang, constructed under the Northern Wei imperial sponsorship near Datong in present-day Shanxi Province, were decorated with sculptural images made after Indian models. The earlier archaic style began to change as a result of increasing diplomatic contacts between North and South China, particularly after a series of reform policies implemented by Emperor Xiaowen (r. 47199). Marked by the adoption of Chinese language, costume, and political institutions, the Northern Wei reform contributed greatly to an artistic and cultural amalgamation in sixth-century China, which was also manifested in painting, calligraphy, the funerary and decorative arts, and the style of the cave-temples at Longmen in Henan Province. The end of the Northern and Southern Dynasties also saw the beginning of a large influx of foreign immigrants, most of whom were traders or Buddhist missionaries from Central Asia. Some settled in China and held official posts; they adopted the Chinese way of life, but maintained their own social customs and practiced native religions. By the time China was united again under the Sui (581618), the country had already experienced decades of relative political stability and social mobility, and its continuous receptiveness to outside influences prepared the way for the advent of the

most glorious and prosperous epoch in its historythe Tang dynasty (618 906).

Northern Wei The Northern Wei Dynasty, also known as the Tuoba Wei, Later Wei, or Yuan Wei, was a dynasty which ruled northern China from 386 to 534 (de jure until 535). Described as "part of an era of political turbulence and intense social and cultural change",[6]the Northern Wei Dynasty is particularly noted for unifiying northern China in 439: this was also a period of introduced foreign ideas; such as Buddhism, which became firmly established. Many antiques and art works, both Daoist and Buddhist, from this period have survived. During the Taihe period (477-499) ofEmperor Xiaowen, court advisers instituted sweeping reforms and introduced changes that eventually led to the dynasty moving its capital from Datong toLuoyang, in 494. It was the time of the construction of the Buddhist cave sites of Yungang by Datong during the mid-to-late 5th century, and towards the latter part of the dynasty, the Longmen Caves outside the later capital city of Luoyang, in which more than 30,000 Buddhist images from the time of this dynasty have been found. It is thought the dynasty originated from the Tuoba clan of the Xianbei tribe. The Tuoba renamed themselves the Yuan as a part of systematic Sinicization. Towards the end of the dynasty there was significant internal dissension resulting in a split into Eastern Wei Dynasty and Western Wei Dynasty. Sinicization As the Northern Wei state grew, the emperors' desire for Han Chinese institutions and advisors grew. Cui Hao (381-450), an advisor at the courts in Datong played a great part in this process.[7] He introduced Han Chinese administrative methods and penal codes in the Northern Wei state,

as well as creating a Taoist theocracy that lasted until 450. The attraction of Han Chinese products, the royal court's taste for luxury, the prestige of Chinese culture at the time, and Taoism were all factors in the growing Chinese influence in the Northern Wei state. Chinese influence accelerated during the capital's move to Luoyang in 494 and Emperor Xiaowen continued this by establishing a policy of systematic sinicization that was continued by his successors. Xianbei traditions were largely abandoned. The royal family took the sinicization a step further by changing their family name to Yuan. Marriages to Chinese families were encouraged. With this, Buddhist temples started appearing everywhere, displacing Taoism as the state religion. The temples were often created to appear extremely lavish and extravagant on the outside of the temples. Breakup and Division The heavy Chinese influence that had come into the Northern Wei state which went on throughout the 5th century had mainly affected the courts and the upper ranks of the Tuoba aristocracy. Armies that guarded the Northern frontiers of the empire and the Xianbei people who were less sinicized began showing feelings of hostility towards the aristocratic court and the upper ranks of civil society. Early in Northern Wei history, defense on the northern border against Rouran was heavily emphasized, and military duty on the northern border was considered honored service that was given high recognition. After all, throughout the founding and the early stages of the Northern Wei, it was the strength of the sword and bow that carved out the empire and kept it. But once Emperor Xiaowen's sinicization campaign began in earnest, military service, particularly on the northern border, was no longer considered an honorable status, and traditional Xianbei warrior families on the northern border were disrespected and disallowed many of their previous privileges, these warrior families who had originally being held as the upper-class now found themselves considered a lower-class on the social hierarchy. In 523, rebellions broke out on six major garrison-towns on the northern border and spread like wildfire throughout the north. These rebellions lasted for a decade. Exacerbating the situation,Empress Dowager Hu poisoned her own son Emperor Xiaoming in 528 after Emperor Xiaoming showed disapproval of her handling of the affairs as he started coming of age and got ready to reclaim the power that had been held by the empress in his name when he inherited the throne as an infant, giving the Empress Dowager rule of the country for more than a decade. Upon hearing the news of the 18-year-old emperor's death, the general Erzhu Rong, who had already mobilised on secret orders of the emperor to support him in his struggle with the Empress Dowager Hu, turned toward Luoyang. Announcing

that he was installing a new emperor chosen by an ancient Xianbei method of casting bronze figures, Erzhu Rong summoned the officials of the city to meet their new emperor. However, on their arrival, he told them they were to be punished for their misgovernment and butchered them, throwing the Empress Hu and her candidate (another puppet child emperorYuan Zhao) into the Yellow River. Reports estimate 2,000 courtiers were killed in this Heyin (Ho-Yin) massacre on the 13th day of the second month of 528. The Two Generals

Erzhu dominated the imperial court thereafter, the emperor held power in name only and most decisions actually went through the Erzhu, although he did put out most of the rebellions, largely reunifying the Northern Wei state. However, Emperor Xiaozhuang, not wishing to remain a puppet emperor and highly wary of the Erzhu clan's widespread power and questionable loyalty and intentions towards the throne (after all, this man had ordered a massacre of the court and put to death a previous emperor and empress before), killed Erzhu Rong in 530 in an ambush at the palace, which lead to a resumption of civil war, initially between Erzhu's clan and Emperor Xiaozhuang, and then, after their victory over Emperor Xiaozhuang in 531, between the Erzhu clan and those who resisted their rule. In the aftermath of these wars, two generals set in motion the actions that would result in the splitting of the Northern Wei into the Eastern and Western Wei.

General Gao Huan was originally from the northern frontier, one of many soldiers who had surrendered to Erzhu, who eventually became one of the Erzhu clan's top lieutenants. But later, Gao Huan gathered his own men from both Han and non-Han troops, to turn against the Erzhu clan, entering and taking the capital Luoyang in 532. Confident in his success, he set up a nominee emperor on the Luoyang throne and continued his campaigns abroad. The emperor, however, together with the military head of Luoyang, Husi Chun, began to plot againstGao Huan. Gao Huan succeeded, however, in keeping control of Luoyang, and the unfaithful ruler and a handful of followers fled west, to the region ruled by the powerful warlord Yuwen Tai. Gao Huan then announced his decision to move the Luoyang court to his capital city of Ye. "Within three days of the decree, 400,000 families--perhaps 2,000,000 people--had to leave their homes in and around the capital to move to Yeh as autumn turned to winter."[9] There now existed two rival claimants to the Northern Wei throne, leading to the state's division in 534-535 into the Eastern Wei and Western Wei.

Fall Neither Eastern Wei nor Western Wei was long-lived. In 550, Gao Huan's son Gao Yang forcedEmperor Xiaojing of Eastern Wei to yield the throne to him, ending Eastern Wei and establishing the Northern Qi. Similarly, in 557, Yuwen Tai's nephew Yuwen Hu forced Emperor Gong of Western Wei to yield the throne to Yuwen Tai's son Yuwen Jue, ending the Western Wei and establishing the Northern Zhou, finally extinguishiing Northern Wei's imperial rule.

You might also like

- History of China: Historical SettingDocument4 pagesHistory of China: Historical Settingcamiladcoelho4907No ratings yet

- Chinese Cultural StudiesDocument40 pagesChinese Cultural Studiesvkjha623477No ratings yet

- 22 Record of Buddhist Monasteries in LuoyangDocument3 pages22 Record of Buddhist Monasteries in LuoyangsdfkdnbvbrNo ratings yet

- 05 Política e Sociedade Chinesa (Inglês)Document42 pages05 Política e Sociedade Chinesa (Inglês)LuizFernandoChagasNo ratings yet

- Concise Political History of ChinaDocument34 pagesConcise Political History of Chinagsevmar100% (1)

- Chinese Civilization through DynastiesDocument9 pagesChinese Civilization through DynastiesAubrey Marie VillamorNo ratings yet

- Asian HistoryDocument10 pagesAsian HistoryMa. Paula Fernanda Cuison SolomonNo ratings yet

- Tsukamoto Zenryu Ch. 6 A History of Early Chinese BuddhismDocument149 pagesTsukamoto Zenryu Ch. 6 A History of Early Chinese BuddhismjaholubeckNo ratings yet

- 1Document17 pages1Jaromohom AngelaNo ratings yet

- Chinese Dynasties: XIA DYNASTY: 2000 - 1500 BCDocument14 pagesChinese Dynasties: XIA DYNASTY: 2000 - 1500 BCupsidedownwalker100% (3)

- Chinese Dynasties: Xia or Hsia c.2205 - c.1766 B.C.EDocument3 pagesChinese Dynasties: Xia or Hsia c.2205 - c.1766 B.C.EThangNo ratings yet

- History of China 1Document29 pagesHistory of China 1olympiaNo ratings yet

- Prehistory of AsiaDocument6 pagesPrehistory of AsiaRonaldNo ratings yet

- Eastern-CivDocument37 pagesEastern-CivFritz louise EspirituNo ratings yet

- Imperial China: Qin Dynasty (221 - 206 BC)Document15 pagesImperial China: Qin Dynasty (221 - 206 BC)accountingtutor01No ratings yet

- Tsukamoto Zenryu CH 1 A History of Early Chinese BuddhismDocument40 pagesTsukamoto Zenryu CH 1 A History of Early Chinese BuddhismjaholubeckNo ratings yet

- ChinaX Transcript Week 11-BuddhismDocument27 pagesChinaX Transcript Week 11-BuddhismMarian CullenNo ratings yet

- Emperor Gaozu of HanDocument7 pagesEmperor Gaozu of HanLester DesalizaNo ratings yet

- Shang and Zhou Dynasties: The Bronze Age of China - Early Civilization | Ancient History for Kids | 5th Grade Social StudiesFrom EverandShang and Zhou Dynasties: The Bronze Age of China - Early Civilization | Ancient History for Kids | 5th Grade Social StudiesNo ratings yet

- History of ChinaDocument3 pagesHistory of ChinaCharles Daniel RosiosNo ratings yet

- New Ctive o He Uppre Ssion of Uddhi Ring e Ern Wei: On TH Ance of Thnicity N El Gion NM HinaDocument2 pagesNew Ctive o He Uppre Ssion of Uddhi Ring e Ern Wei: On TH Ance of Thnicity N El Gion NM HinaDavid SlobadanNo ratings yet

- ChinaDocument12 pagesChinaLimeylen IsNoobNo ratings yet

- Chinese Dynasties For StudentsDocument4 pagesChinese Dynasties For StudentsmatreatNo ratings yet

- Origins of Ancient China's First Dynasty - The Xia DynastyDocument6 pagesOrigins of Ancient China's First Dynasty - The Xia DynastycorneliuskooNo ratings yet

- Ancient Chinese History: The Foundation of a Nation/TITLEDocument83 pagesAncient Chinese History: The Foundation of a Nation/TITLEtaufiq ahmedNo ratings yet

- Shang DynastyDocument1 pageShang DynastyshivamguptaNo ratings yet

- Class NotesHistory of China With Detalied Explanation Up Until Covid19Document44 pagesClass NotesHistory of China With Detalied Explanation Up Until Covid19gideonNo ratings yet

- Yangtze International Study Abroad: Oracle Bones (jiăgŭwén - 甲骨文)Document77 pagesYangtze International Study Abroad: Oracle Bones (jiăgŭwén - 甲骨文)Anonymous QoETsrNo ratings yet

- Han and Qin Dynasty (Kristian's Report)Document11 pagesHan and Qin Dynasty (Kristian's Report)Stacey Kate ComerciaseNo ratings yet

- Xin DynastyDocument3 pagesXin DynastyVu PhilNo ratings yet

- Early China and Nubia: Geography, Agriculture, and KingdomsDocument7 pagesEarly China and Nubia: Geography, Agriculture, and KingdomsJosh ParkNo ratings yet

- Tang SongDocument7 pagesTang SongMeredith BanksNo ratings yet

- The Xia, Shang, and Zhou Dynasties in Ancient ChinaDocument4 pagesThe Xia, Shang, and Zhou Dynasties in Ancient Chinasprite_phx073719No ratings yet

- Chinese Literature History & CultureDocument10 pagesChinese Literature History & CultureNatabio, Johannah N.No ratings yet

- China's Ancient DynastiesDocument25 pagesChina's Ancient DynastiesAhmad AtimNo ratings yet

- History of KoreaDocument3 pagesHistory of KorearaigainousaNo ratings yet

- Chinese History Analysis According To PROUT Economic TheoryDocument54 pagesChinese History Analysis According To PROUT Economic TheoryTapio PentikainenNo ratings yet

- Ancient China HistoryDocument12 pagesAncient China HistoryHyun Sairee VillenaNo ratings yet

- The Uighurs and ShambalaDocument9 pagesThe Uighurs and Shambalacatalina nicolinNo ratings yet

- HS-HSS-EAIP-Part 3 - Chapter 10 - Inner and East Asia 600-1200Document24 pagesHS-HSS-EAIP-Part 3 - Chapter 10 - Inner and East Asia 600-1200Shaan PatelNo ratings yet

- Ancient China EditedDocument78 pagesAncient China Editedchuron0% (1)

- The Shang Dynasty: Government and Society Order Agricultural SocietyDocument37 pagesThe Shang Dynasty: Government and Society Order Agricultural SocietyKhristine Joy NovidaNo ratings yet

- Confucius timeline major events life legacyDocument3 pagesConfucius timeline major events life legacyamtbNo ratings yet

- History of Ancient China in 40 CharactersDocument195 pagesHistory of Ancient China in 40 Charactersaditya00012No ratings yet

- Chinese CivilizationDocument44 pagesChinese CivilizationAlex Sanchez100% (1)

- Case Study Tech Culture DynDocument30 pagesCase Study Tech Culture DynHomework PingNo ratings yet

- Chinese World Order John K. Fairbank.Document39 pagesChinese World Order John K. Fairbank.Nasri Azlan100% (1)

- Chinese Civilizations: Dynasties, Philosophy, and CultureDocument8 pagesChinese Civilizations: Dynasties, Philosophy, and CultureNegielyn SubongNo ratings yet

- Xia DynastyDocument1 pageXia DynastyEdelyn AlmiranesNo ratings yet

- Records of The Grand Historian Bamboo AnnalsDocument2 pagesRecords of The Grand Historian Bamboo Annalsaccountingtutor01No ratings yet

- Legal System of ChinaDocument92 pagesLegal System of ChinaAndreij TjakraningratNo ratings yet

- Eastern Zhou Dynasty (770 - 221 B.C.)Document1 pageEastern Zhou Dynasty (770 - 221 B.C.)ThangNo ratings yet

- AssignmenDocument27 pagesAssignmenNur Munirah50% (2)

- Music of ChinaDocument43 pagesMusic of ChinaJcee EsurenaNo ratings yet

- 14-2 OahwdiughaDocument4 pages14-2 OahwdiughaRichard ShiauNo ratings yet

- Lesson 4 - Ancient Civilization in ChinaDocument31 pagesLesson 4 - Ancient Civilization in Chinaapi-269480354No ratings yet

- The Shang Dynasty Oracle Texts and Ritual Bronzes: Indiana University, EALC E232, R. Eno, Spring 2008Document8 pagesThe Shang Dynasty Oracle Texts and Ritual Bronzes: Indiana University, EALC E232, R. Eno, Spring 2008murkyNo ratings yet

- Ladia Corpo Lecture Part 4 (June 8)Document8 pagesLadia Corpo Lecture Part 4 (June 8)Khaiye De Asis AggabaoNo ratings yet

- GPS Tracking An Invasion of PrivacyDocument11 pagesGPS Tracking An Invasion of PrivacycardeguzmanNo ratings yet

- Land Titling PDFDocument51 pagesLand Titling PDFcardeguzmanNo ratings yet

- Partnership and Agency Digests For Atty. CochingyanDocument28 pagesPartnership and Agency Digests For Atty. CochingyanEman Santos100% (3)

- Responsibility of non-state actors for protecting internally displaced personsDocument2 pagesResponsibility of non-state actors for protecting internally displaced personscardeguzmanNo ratings yet

- Ladia Corpo Lecture 1 (June 9)Document9 pagesLadia Corpo Lecture 1 (June 9)Ruel Benjamin BernaldezNo ratings yet

- Dratw Philippines 2011 PDFDocument59 pagesDratw Philippines 2011 PDFcashielle arellanoNo ratings yet

- Waiver of RightsDocument1 pageWaiver of RightscardeguzmanNo ratings yet

- Jurisdiction in Civil CasesDocument8 pagesJurisdiction in Civil CasesChester Pryze Ibardolaza TabuenaNo ratings yet

- Civ 2 CaseDocument40 pagesCiv 2 CasecardeguzmanNo ratings yet

- Criminal Case Evidence SummaryDocument3 pagesCriminal Case Evidence Summarycardeguzman80% (5)

- Anti-Illegal Drugs Special Operations Task Force ManualDocument97 pagesAnti-Illegal Drugs Special Operations Task Force ManualAntonov FerrowitzkiNo ratings yet

- EthicsDocument2 pagesEthicscardeguzmanNo ratings yet

- Film analysis of A Few Good MenDocument2 pagesFilm analysis of A Few Good Mencardeguzman50% (2)

- Armed Conflict and DisplacementDocument34 pagesArmed Conflict and DisplacementcardeguzmanNo ratings yet

- Arellano Outline Land ClassificationDocument6 pagesArellano Outline Land ClassificationZan BillonesNo ratings yet

- Film Analysis Guilty by SuspicionDocument2 pagesFilm Analysis Guilty by SuspicioncardeguzmanNo ratings yet

- Full Legres CasesDocument58 pagesFull Legres Casescardeguzman100% (1)

- LTD Outline Land TitlingDocument51 pagesLTD Outline Land TitlingClaire Roxas100% (2)

- Appellate TableDocument2 pagesAppellate TablecardeguzmanNo ratings yet

- EthicsDocument2 pagesEthicscardeguzmanNo ratings yet

- Appellate's BriefDocument32 pagesAppellate's BriefcardeguzmanNo ratings yet

- Civ Pro Mid Term Exam - Flattened-1Document10 pagesCiv Pro Mid Term Exam - Flattened-1cardeguzmanNo ratings yet

- Cases in Land RegistrationDocument3 pagesCases in Land RegistrationcardeguzmanNo ratings yet

- Land Titling Guide for the PhilippinesDocument48 pagesLand Titling Guide for the PhilippinescardeguzmanNo ratings yet

- Aban Tax 1 Reviewer PDFDocument67 pagesAban Tax 1 Reviewer PDFcardeguzmanNo ratings yet

- Special Proceeding Reviewer (Regalado)Document36 pagesSpecial Proceeding Reviewer (Regalado)Faith Laperal91% (11)

- Estate, donor, VAT, excise tax reviewerDocument3 pagesEstate, donor, VAT, excise tax reviewercardeguzmanNo ratings yet

- Land DispositionDocument27 pagesLand Dispositioncardeguzman100% (1)

- Tax2 - Local Taxation ReviewerDocument4 pagesTax2 - Local Taxation Reviewercardeguzman88% (8)

- Cassiodorus and The Getica of JordanesDocument19 pagesCassiodorus and The Getica of JordanesthraustilaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7 TestDocument2 pagesChapter 7 Testapi-41164603100% (3)

- Pacs NZBDocument28 pagesPacs NZBksm256No ratings yet

- Bertie County NC Loose Estates IndexDocument50 pagesBertie County NC Loose Estates IndexNCGenWebProjectNo ratings yet

- Kathryn Kuhlman - The Holy SpiritDocument1 pageKathryn Kuhlman - The Holy SpiritAnonymous tXpFHNGo7Q100% (5)

- Symbolism WorksheetDocument1 pageSymbolism Worksheetamandaarief7No ratings yet

- List of Contesting CandidatesDocument34 pagesList of Contesting CandidatesSajid Bhai ShaikhNo ratings yet

- Historiography of The Moro KulintangDocument14 pagesHistoriography of The Moro KulintangTinay CendañaNo ratings yet

- Movie ImdbDocument339 pagesMovie ImdbF YoutubeNo ratings yet

- The Origin and Development of SambaDocument10 pagesThe Origin and Development of Sambasjensen495No ratings yet

- A Gender Friendly Generator of 300 Viking NamesDocument8 pagesA Gender Friendly Generator of 300 Viking NamesDanielNo ratings yet

- 40 Ex II 2 PDFDocument244 pages40 Ex II 2 PDFKeshev KumarNo ratings yet

- A-Z Airfreight Directory - Cargo Agents - Freight Forwarders - Saudi ArabiaDocument19 pagesA-Z Airfreight Directory - Cargo Agents - Freight Forwarders - Saudi ArabiaSanthosh K MararNo ratings yet

- Sherlock Holmes Adventure - A Scandal in BohemiaDocument210 pagesSherlock Holmes Adventure - A Scandal in BohemiaElias Matheus OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Cecil Hurt Special Section Page 5Document1 pageCecil Hurt Special Section Page 5USA TODAY NetworkNo ratings yet

- CPAR National Artist (Ryan Cayabyab)Document2 pagesCPAR National Artist (Ryan Cayabyab)Jan Henry Timothy BolivarNo ratings yet

- The Word in Pictures: Stephen Is MartyredDocument5 pagesThe Word in Pictures: Stephen Is Martyredmilu1312No ratings yet

- Macbeth Assignment 2017Document5 pagesMacbeth Assignment 2017anastasiiaNo ratings yet

- Ordo Antichristianus Illuminati Rite of Lilith by Joshua Seraphim © 1999 Leilah Publications LLC. All Rights ReservedDocument26 pagesOrdo Antichristianus Illuminati Rite of Lilith by Joshua Seraphim © 1999 Leilah Publications LLC. All Rights ReservedJeb Morningside100% (2)

- First Name F. Phone No. F. MobileDocument14 pagesFirst Name F. Phone No. F. MobileMukul Kumar100% (1)

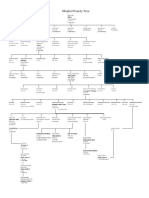

- Mughal Family TreeDocument1 pageMughal Family Treenandi_scr0% (3)

- Koryak Texts - Bogoras, Waldemar (1917)Document172 pagesKoryak Texts - Bogoras, Waldemar (1917)Mikael de SanLeonNo ratings yet

- The Devils DaughterDocument3 pagesThe Devils DaughterSnowLynnxNo ratings yet

- Romania PresentationDocument41 pagesRomania Presentationteacher_trNo ratings yet

- 70 Years of DesolationDocument9 pages70 Years of DesolationdinudatruthseekerNo ratings yet

- Pengaruh Interior Displayexterior Display Promosi Penjualan Dan Lokasi Terhadap Keputusan Pembelian Di Foodmart Basko Kota PadangDocument13 pagesPengaruh Interior Displayexterior Display Promosi Penjualan Dan Lokasi Terhadap Keputusan Pembelian Di Foodmart Basko Kota PadangRadenNo ratings yet

- Giáo Trình Marketing Du Lịch Phần 2 - NXB Tổng Hợp TP.hcmDocument183 pagesGiáo Trình Marketing Du Lịch Phần 2 - NXB Tổng Hợp TP.hcmNgoc HoNo ratings yet

- CCP Npa PresentationDocument41 pagesCCP Npa PresentationThird Man Coy0% (1)

- Os Atos Dos Apóstolos - The Acts of The Apostles - Part 1Document8 pagesOs Atos Dos Apóstolos - The Acts of The Apostles - Part 1freekidstoriesNo ratings yet

- Reach - Volume 3 - Issue 1Document16 pagesReach - Volume 3 - Issue 1Calvary Church of Santa AnaNo ratings yet