Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Lu Xun Mo Yan Final

Uploaded by

Patrick KilianOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Lu Xun Mo Yan Final

Uploaded by

Patrick KilianCopyright:

Available Formats

Kilian 1

Patrick Kilian Dr. Shelly Chan CHIN 330C 10 May 2010 Re-humanizing China: Animal Imagery in Mo Yan as a Response to Lu Xun

All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others. - Animal Farm

The Father of modern Chinese literature, one Lu Xun, the pen name of Zhou Shuren, once said: Suppose there were an iron room with no windows or doors, a room it would be virtually impossible to break out of. And suppose you had some people inside that room who were sound asleep. Before long they would all suffocate. In other words, they would slip peacefully from a deep slumber into oblivion, spared the anguish of being conscious of their impending doom. Now lets say that you came along and stirred up a big racket that awakened some of the lighter sleepers. In that case, they would go to a certain death fully conscious of what was going to happen to them. Would you say that you had done those people a favor? (Preface 27)

The iron house Lu Xun refers to here represents the state of the hearts and minds of the Chinese people at the time of his writing, which he himself dates December 3, 1922. His notion and purpose for writing his plethora of works hinges on this idea; the idea that through the written word he and contemporaries could wake up the Chinese population, which he viewed as suffering from a crippling apathy and immovably backward and self-destructive culture. Across

Kilian 2

his works, Lu Xun utilizes animal imagery, the comparison between animal and Chinese person having the general effect of displaying the dehumanized state of the Chinese people as a whole. Years later, prolific author Mo Yan, pen name of one Guan Moye, also includes droves of animal descriptions metaphors, pure images, even principal characters, yet does so with an entirely different intent than his illustrious predecessor. Though both animal and human are treated with Mo Yans violent and disturbing pen, his animals serve to re-humanize his human characters by removing a sense of judgment and, in so doing, attempt to heal his nation from its decades upon decades of suffering. Lu Xuns first and most famous short story, Diary of a Madman, begins this dialogue. It starts in the mad mans very first entry with the sentence, Otherwise, how do you explain those dirty looks the Zhao familys dog gave me? Ive got good reason for my fears (Diary of a Madman 30). This initial glimpse of animal usage sets up Lu Xuns argument; the mad man fears that the dog wants to eat him; ergo the reader understands that animals eat people. When the mad man later reveals his different understanding of the history book, seeing the words Eat people on every page, Lu Xun links animal behavior to Chinas history, arguing that the China has created a culture that dehumanizes, numbs, and ultimately self-sabotages its people. Structurally, Lu Xun takes a bold step in this piece. Often cited as the first example of colloquial Chinese language in a piece of literature, the main body, comprised of the mad mans journal entries themselves, contains all of these references to animals. The brief introduction, on the other hand, which is written in the classical Chinese style of terse formality and lofty intellectual tradition, contains absolutely none. Written by a third party after the mad mans reported cure, the introduction reads, By now, however, he had long since become sound and fit again; in fact he had already repaired to other parts to await a substantive official

Kilian 3

appointment (Diary of a Madman 29). The mad man, once a visionary appalled with the cultural cannibalism shown in the pages of Chinese historical thought wherein no dates signify an indefinite and everlasting period of abuse, in the end reverts to the old ways and becomes a part of the system itself. Following the initial argument comparing humans with dogs (a comparison that Mo Yan repeats several times in various works discussed later), Lu Xun peppers the imaginings of his titular mad man with animal thoughts. These thoughts echo and reverberate throughout the piece, from the mad mans citing of the cannibalistic incident in Wolf Cub Village to the cryptic comment, The Zhao familys dog has started barking again. Savage as a lion, timid as a rabbit, crafty as a fox (Diary of a Madman 35). While at first glance this quotation attributes itself the ravings of the crazed man the protagonist appears to be, Lu Xun consistently puts his message in the mouth of characters on the outside of a societal norm. Here, his process of deterritorialization should lead the reader back to the initial argument; the Zhao family dog equates to the wary mob, threatened by the Other it cannot understand. The Chinese people here possessing the qualities of savagery, see its violent and repeated destruction of itself, timidity, see its reticence to accept any change to its own perceived cultural superiority, and craft, that is, the society hides its behavior in insidious ways including Confucian-schooled concepts of filial piety. The mad mans meal of fish is a particularly powerful metaphor; the fish with its blank, lifeless eyes that can do nothing but stare open-mouthed at its devourer mirrors the photographs of onlookers at executions that Lu Xun found so repulsive. The mad man remarks, The fishs eyes were white and hard. Its mouth was wide open, just like the mouths of those people who wanted to eat human flesh (Diary of a Madman 32-33). Those people are no better than dead

Kilian 4

fish, he says. In the act of eating this fish, though he immediately vomits it out of his system, reinforces the idea that all of China has partaken of this blasphemous meal, including the only soul in the nation who notices the essential wrongness of it. Towards the end, when the diary entries become successively shorter and less coherent, the protagonist questions, Whos to say I didnt eat a few pieces of my younger sisters flesh without knowing it? Although I wasnt aware of it in the beginning, now that I know Im someone with four thousand years experience of cannibalism behind me, how hard it is to look real human beings in the eye! (Diary of a Madman 41). This passage accomplishes two things: first, it shows that even non-participants in Chinas social trends become caught up in the cultural norm an idea peculiar to Chinas enormous emphasis on a collective lifestyle and consciousness. Second, the mad mans shame at facing real human beings, that is, people who do not practice the metaphorical cannibalism, displays a loss of face felt by the author at seeing his country so easily dominated by foreign powers of the time, be they Japan, Russia, the United States, or a myriad of European colonial interests. Further noteworthy, translator William Lyell remarks in a footnote that Darwins theory of evolution was immensely important to Chinese intellectuals during Lu Xuns lifetime and the common coin of much discourse (Diary of a Madman 38). From a certain direction, Darwins theories can be used as evidence to indicate that humans evolved from animals and therefore must have animal qualities; that the human is only as much above the animal as science has allowed it to become. This Western thought, seen again in the phonetic spelling of hyena as hai-yi-na, then indicates an extremely strong advocacy to modernize Chinas sciences and technologies, as these things are a direct path away from animal behavior and away from selfdestructive backwardness (Diary of a Madman 36).

Kilian 5

In his 1919 story Kong Yiji, Lu Xun creates a character emblematic of the Chinese intellectual; well versed in the most ancient of classical texts, unable to generate revenue with his education, resorting to stealing writing supplies from his employers and fencing them to survive, and most of all, too proud to accept other forms of work. The character, Kong Yiji, meets with a sordid and inglorious end, in which the narrator notes: As he handed [the coppers] to me, I noticed his palm was caked with mud. So hed dragged himself there on his hands! Before long, he had finished his wine and then, amid the talk and laughter of the other customers, he laboriously hauled himself away on those same muddy hands. (Kong Yiji 47-48)

Kongs legs have been broken for his thievery and he is therefore forced to crawl in the mud as would an animal, debasing himself in front of a community he has, for his entire life, believed himself to be above. At his end, he finds himself literally below the common peasant as well as being unable to pay his outstanding debts to the low-class bartender. Kong Yiji makes a mockery of this type of stubbornly traditional intellectual, stating that Chinas brightest minds are no better than snakes crawling on their bellies through a mire of antiquated dogmas. In another of his stories, Upstairs in a Wine Shop, Lu Xun again berates the thinking minds of his countrymen (himself included). The character of L Weifu says: When I was a kid, I used to think that bees and flies were absurd and pathetic. Id watch the way theyd light someplace, get spooked by something, and then fly away. After making a small circle, theyd always come back again and land just exactly where they had been before. Who could have imagined that someday, having made my own small circle, I would fly back too? And who would ever have expected that you would do the same thing? Couldnt you have managed to fly a little farther away? (Upstairs in a Wine Shop 246)

Kilian 6

The metaphor is quite involved. First, the fact that the friend is comparing himself, and by extension reformist intellectuals and people in general, to insignificant insects shows Lu Xuns pessimism and feelings of impotency to affect any great social change. Second, the circular flight path taken by the fly is an interesting shape: circles have no end and imply cyclical events or motions. Therefore, Lu Xun implies that Chinas attempted social reform is a consistent trend throughout the ages that never gets very far. Finally, the friends ending comments on the teaching of the Confucian Classics express this same sentiment and display how even the most well-meaning individuals fall back into the old and the comfortable. Essentially, L Weifu makes an even more damning metaphor than Kong Yiji. His equates the man to a pestilential vermin feeding on the already failing society. The very last words in Lu Xuns Diary of a Madman are a plea to his fellow countrymen to wake up from the suffocating slumber of the iron house and enact the changes necessary for China to heal from its destructive past. The mad man writes, Maybe there are some children around who still havent eaten human flesh. Save the children (Diary of a Madman 41). Mo Yan, who did not arrive on the scene until 1955, embodies writes with the spirit of this charge in mind. He conjures the most violent and grotesque images possible and yet after shocking his readership with the horrifying choices and actions of his protagonists and other characters, leaves an indelible liking for them, as if all forms of judgment have been removed. Mo Yans characters, especially of Red Sorghum, his first published novel, The first major instance where Mo Yan uses animals in an uncommon way is when Uncle Arhat maims and kills the two black mules in order to slow down the Japanese road project. Mo Yan repeatedly personifies the animals in Red Sorghum, most of all the mules and/or donkeys as well as the dogs. In the aforementioned quote, Uncle Arhats thoughts form the sentence, Time to

Kilian 7

free his comrades in suffering, and as he lames the first mule with a hoe he curses the mule: Wheres your arrogance now? You evil ungrateful, parasitic bastard! You ass-kissing, treacherous son of a bitch! (Red Sorghum 22-23). The description of Uncle Arhats physical violence against these animals does not differ at all in its treatment from Mo Yans description of violence toward his human characters either, up to and including the level of disturbing detail. This particular passage ends, The wounded animal then arched its rump, sending a shower of hot blood splashing down on Uncle Arhats face The shiny wooden handle [of the hoe] buried in the mules head pointed to heaven at a jaunty angle (Red Sorghum 23). In his singular treatment of both animal and man, Mo Yan elevates the animals to the level of relatable human characters and at the same time continues Lu Xuns tradition of equating humans with beasts. The third chapter of Red Sorghum, entitled Dog Ways, . In its opening sentence, Mo Yan says, The glorious history of man is filled with legends of dogs and memories of dogs: despicable dogs, respectable dogs, fearful dogs, pitiful dogs (Red Sorghum 169). This comment, while establishing the link between dog, man, and historical action, also indicates that the glorious history of man is full of myths and remembrances of humans. These historical figures cover all shades of the human emotional spectrum as well as all types of person, from the best and most worthy of humankind to the lowest and most despicable. History and death, Mo Yan shows, treat all of them equally. As the youthful Father describes his work re-burying human and dog skeletons at a mass grave site, he says: A momentary dizziness came over me, and when it passed I took another look, discovering the skulls of dozens of dogs mixed in with the human heads in the grave. The bottom of the pit was a shallow blur of white, a sort of code revealing that the history of dogs and the history of man are intertwined. (Red Sorghum 204)

Kilian 8

Again, Father thinks, when it came to the large canine skull I hesitated. Toss it in, an old man said, the dogs back then were as good as humans (Red Sorghum 204). If dogs are as good as humans, then any mongrel is as good as the phenomenally likeable Grandma and Grandpa characters of this drama, characters, who to be sure do their share of morally questionable deeds and yet emerge from them pure and whole. Continuing his theme of dogs, Mo Yans White Dog Swing in large part engages in a literary dialogue with Lu Xuns story, New Years Sacrifice. Mo Yan presents his own version of the intellectual narrator with his own, also nameless, city-living-elite-come-home, and his own depiction of the famous Xianglin Sao in the unfortunate Nuan. The two narrators share a remarkable amount of characteristics, possibly because Lu Xun and Mo Yan also have them in common: both are wanderers, they belong neither to their ancestral homes and rural upbringings nor to their new citified environs, and are wracked, therefore, with bouts of nostalgia. In their essential characters however, the two are polar opposites, as seen in their respective treatments of the marginalized Other at the ending of each story. Whereas Lu Xuns intellectual ultimately relegates Xianglin Saos sad tale to the realm of forgetfulness; All the worries and concerns that had plagued me from morning till night the day before had been totally swept away by the happy atmosphere of the New Year, Mo Yans narrator remains a sympathetic and caring individual (New Years Sacrifice 241). In the final two pages of White Dog Swing, Mo Yan makes use of over twenty ellipses, up to and including ending the story with their associated pause. This hesitation in the writing and dialogue displays the narrators guilt over the events of ten years ago when he inadvertently caused Nuans scarring injury. This narrator even explains, I looked at the desperate expression on her face and was choked with emotion: Of course I would have [married you], of course I

Kilian 9

would (Mo Yan, 23). This level of compassion in an intellectual character, completely alien to Lu Xuns works, suggests that the people that Lu Xun sought to wake from the stupor of the Iron House are slowly rousing themselves. Their world and society is fraught with inequities and hardships, true, but there is a subtle growth evidenced here that is difficult to ignore. In another novel, Big Breasts and Wide Hips, the central figure, Mother, once again equates human and animal. She says, Humans and animals are so much alike Malory nodded in agreement (Big Breasts and Wide Hips 94). The opening chapter, the parallel births of the mule and Mothers eighth and ninth children, bears significantly on this case. All three offspring are bastard offspring in the sense of being half-breeds: the young mule is the sterile child of a donkey and a horse, while Yun and Jintong, Mothers eighth daughter and the male narrator respectively, are the multi-racial children of Shangguan Lu, the strong central figure of the Chinese woman, and Pastor Malory the foreign Swede (Big Breasts and Wide Hips 94). Of further significance, Shangguan L, or Mothers mother-in-law, places the donkeys birthing before her own family line! Not only that, but Mother seems to understand this hierarchy: You go on Mother, Shangguan Lu said emotionally, Lord in Heaven, keep the Shangguan familys black donkey safe, let her foal without incident (Big Breasts and Wide Hips 7). In effect, this simultaneous birthing that comprises the entire first act of Mo Yans family saga places all potential blame for the characters poor treatment of each other on the various systems that operated in their lives. Specifically, Shangguan Ls care for the donkey over her daughter-in-law condemns the Chinese preoccupation with producing a son in order to carry on the family name. Jintong, the eventual son, becomes a grotesque mockery of a man while his mother, Shangguan Lu maintains her position as a bastion of strength and support for multiple generations of her family and the community. Social and political pressures operate on

Kilian 10

this Jintong and warp him from birth into a subhuman creature that can barely survive in the modern world, and once again, Finally, in his novel Life and Death are Wearing Me Out, Mo Yan performs a more overt association between animal and human: the main character begins the story dead and subsequently is reincarnated six times as progressively more human-like animals; first a donkey, then an ox, a pig, a dog, a monkey, and finally as a boy with an enormous head. While still a dead soul in King Yamas underworld, the protagonist, Ximen Nao, refuses to forget his past life in exchange for a better new one, saying, I want to hold on to my suffering, worries, and hostility. Otherwise, returning to that world is meaningless (Life and Death 6). The grudges that Ximen Nao holds against those who betrayed and executed him play out over these six lives. Ultimately, Mo Yans message indicates that the blame and the hatred that Ximen Nao has in his heart hold him back. To let them go, to realize that human beings do terrible things and to forgive those who do leads to the tranquility of the Buddhist saying that serves as the epigraph for this novel. As Ximen Donkey, the protagonist rails at his former life and human memories intruding upon the simplicity of a donkey seeking its mate. He thinks, Ximen Nao, you goddamned Ximen Nao, stay out of my business. I am now a donkey with the fires of lust burning inside me. When Ximen Nao enters the picture, even if its only his recollections, the result is a recapitulation of a bloody, corrupt history (Life and Death 54). The copulation and resulting amorous connection between Ximen Donkey and the female, Huahua, makes a mockery of the human practice of taking concubines with its fidelity and purity, again supported by the repulsive character of Qiuxiang. Not content there however, Mo Yan redeems even Qiuxiang in her quiet aid for Lan Lian when he has paint in his eyes.

Kilian 11

In The Strength of an Ox, Mo Yan criticizes the excesses and quasi-religious fanaticism of the Cultural Revolution era and the Red Guard. Concerning their chief representative, Lan Jinlong, his adoptive father Lan Lian remarks, the blood that flows through his veins is more lethal than a scorpions tail. Hell do absolutely anything in the name of revolution (Life and Death 201). Lan Jiefang, a principal narrator and Jinlongs half-brother, fights against Jinlong with every fiber of his being, and yet shows love and compassion for him when he almost dies of cold, and admiration for him in his eventual desire and act of joining the commune in order to become a Red Guard. Jinlong, with whom the narrator Jiefang initially had a good relationship, drives himself to perform nationalistic semi-atrocities because of his birth father, the class-enemy and aristocrat Ximen Nao, whom he never even knew. The legacy that he might have inherited would have placed him at the mercy of the tides of revolution again the institution provides the motive for a characters evils. In the end though, Jinlong suffers the fate of a counter-revolutionary for accidentally dropping a badge depicting Mao Zedong in a latrine, reminding the reader that institutions such as the Chinese Communist government are the antithesis of humanity they are unthinking, unfeeling things that can destroy even their most devoted members. In terms of moral action, animals cannot sin or transgress a moral law of any sort, as they act purely on instinct. Hence argues Mo Yans overarching thought, if human beings act purely according to their desires, at the end of the day, moral blame cannot fall on the heads of the individual person but rather can only fall on a system imposed on him or her. Therefore, communism, socialism, capitalism, government, war, filial piety, marriage, starvation, ideology, religion, and any other far-reaching social category these are the agents of misery in human affairs. The people themselves, each individual human being, in an absence of such imposing

Kilian 12

forces will act according to his nature, in which case he or she will find peace. Since this is virtually impossible in any sort of modern society, Mo Yan writes to reinforce the essential humanity of every person, and make it possible, not to forget the carnage of Chinas history, but forgive it and move on into a better tomorrow.

Kilian 13

Works Cited Deleuze, Gilles, and Flix Guattari. "What Is a Minor Literature?" Mississippi Review 11.3 (1983): 13-33. JSTOR. Web. 5 May 2010. <http://moodle.wittenberg.edu/mod/resource/view.php?id=53107>. Lu Xun. "Diary of a Madman." 1918. Diary of a Madman and Other Stories. University of Hawaii, 1990. 29-41. Print. Lu Xun. "Kong Yiji." 1919. Diary of a Madman and Other Stories. University of Hawaii, 1990. 42-48. Print. Lu, Xun. "New Year's Sacrifice." 1924. Diary of a Madman and Other Stories. University of Hawaii, 1990. 219-41. Print. Lu Xun. "Preface." 1922. Diary of a Madman and Other Stories. University of Hawaii, 1990. 2128. Print. Lu Xun. "Upstairs in a Wineshop." 1924. Diary of a Madman and Other Stories. University of Hawaii, 1990. 242-54. Print. Lu Xun, and Christopher Smith. "White Dog Swing." Chinese Literature 19 Dec. 1989: 3-25. Wittenberg University Thomas Library E-Reserves. Web. 11 May 2010. "Lunch with China's Mo Yan - TIME." Breaking News, Analysis, Politics, Blogs, News Photos, Video, Tech Reviews - TIME.com. Web. 11 May 2010. <http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1973183,00.html>.

Kilian 14

Mo Yan, and Howard Goldblatt. Big Breasts and Wide Hips: a Novel. New York: Arcade Pub., 2004. Print. Mo Yan, and Howard Goldblatt. Life and Death Are Wearing Me Out: a Novel. New York: Arcade Pub., 2008. Print. Mo Yan, and Howard Goldblatt. Red Sorghum: a Novel of China. New York: Penguin, 1994. Print. Orwell, George. Animal Farm. New York: Knopf, 1993. Print.

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Chinese MandarinDocument3 pagesChinese MandarinAlex D.No ratings yet

- Mo Yan - Iron ChildDocument4 pagesMo Yan - Iron ChildPatrick KilianNo ratings yet

- Semantic Roles 2Document11 pagesSemantic Roles 2wakefulness100% (1)

- 5e Lesson PlanDocument7 pages5e Lesson Planapi-512004980No ratings yet

- Holy Quran para 24 PDFDocument26 pagesHoly Quran para 24 PDFkhalid100% (1)

- Journal 11 - Tibet and Dogshit FoodDocument1 pageJournal 11 - Tibet and Dogshit FoodPatrick KilianNo ratings yet

- Iron Child Journal 2Document1 pageIron Child Journal 2Patrick KilianNo ratings yet

- Farewell My Concubine EssayDocument2 pagesFarewell My Concubine EssayPatrick KilianNo ratings yet

- Guess ThesisDocument8 pagesGuess Thesisaflohdtogglebv100% (2)

- OMF001006 GSM Signaling System-BSSAP (BSS)Document27 pagesOMF001006 GSM Signaling System-BSSAP (BSS)sofyanhadisNo ratings yet

- Essay by Ossama Elkaffash On The New Play by Evald Flisar "Take Me Into Your Hands"Document28 pagesEssay by Ossama Elkaffash On The New Play by Evald Flisar "Take Me Into Your Hands"Slovenian Webclassroom Topic ResourcesNo ratings yet

- Speech Audiometry BB 2015Document29 pagesSpeech Audiometry BB 2015354No ratings yet

- MICROLOGIX 1000 - Final PDFDocument14 pagesMICROLOGIX 1000 - Final PDFAnant SinghNo ratings yet

- List of Papyrus Found NewDocument4 pagesList of Papyrus Found NewiSundae17No ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Poem MicroteachingDocument7 pagesLesson Plan Poem MicroteachingSolehah Rodze100% (1)

- UNIT 04 - ArticlesDocument9 pagesUNIT 04 - ArticlesDumitrita TabacaruNo ratings yet

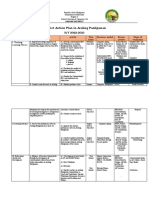

- Action Plan in APDocument4 pagesAction Plan in APZybyl ZybylNo ratings yet

- Computer ProgrammingDocument21 pagesComputer ProgrammingPrabesh PokharelNo ratings yet

- Đề Luyện Thi Học Kỳ 2 Khối 10-11 Cô Phan ĐiệuDocument20 pagesĐề Luyện Thi Học Kỳ 2 Khối 10-11 Cô Phan ĐiệuCarter RuanNo ratings yet

- Qusthan Abqary-Rethinking Tan Malaka's MadilogDocument12 pagesQusthan Abqary-Rethinking Tan Malaka's MadilogAhmad KamilNo ratings yet

- SAM Coupe Users ManualDocument194 pagesSAM Coupe Users ManualcraigmgNo ratings yet

- Information Technology Activity Book Prokopchuk A R Gavrilova eDocument75 pagesInformation Technology Activity Book Prokopchuk A R Gavrilova eNatalya TushakovaNo ratings yet

- Jmeter Pass Command Line PropertiesDocument3 pagesJmeter Pass Command Line PropertiesManuel VegaNo ratings yet

- Comprog ReviewerDocument11 pagesComprog ReviewerRovic VistaNo ratings yet

- ADJECTIVE OR ADVERB Exercises+Document1 pageADJECTIVE OR ADVERB Exercises+Maria Da Graça CastroNo ratings yet

- Jekyll and Hyde Essay TopicsDocument3 pagesJekyll and Hyde Essay TopicsIne RamadhineNo ratings yet

- JAVA PracticalDocument14 pagesJAVA PracticalDuRvEsH RaYsInGNo ratings yet

- Rezty Nabila Putri Exercises EnglishDocument13 pagesRezty Nabila Putri Exercises EnglishRezty NabilaNo ratings yet

- What Is Classic ASPDocument6 pagesWhat Is Classic ASPsivajothimaduraiNo ratings yet

- Brilliant Footsteps Int' Teacher Abdulrahim Ibrahim Lesson Plan & NotesDocument3 pagesBrilliant Footsteps Int' Teacher Abdulrahim Ibrahim Lesson Plan & NotesAbdulRahimNo ratings yet

- The Bible in IndiaDocument236 pagesThe Bible in IndiaabotNo ratings yet

- Lab Report #5 by MungunsukhDocument7 pagesLab Report #5 by MungunsukhoyunpurevoyunaaNo ratings yet

- STTPDocument28 pagesSTTPDarpan GroverNo ratings yet