Professional Documents

Culture Documents

R.piercey - Not Choosing Between Morality and Ethics

Uploaded by

Maria D'uhOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

R.piercey - Not Choosing Between Morality and Ethics

Uploaded by

Maria D'uhCopyright:

Available Formats

Robert Piercey, Not choosing between morality and ethics, The Philosophical Phorum, Volume XXXII, No.

1, Spring 2001 During the last few decades, it has become common to distinguish morality from ethics. Morality, as the term is usually used, is a peculiarly modern type of practical reasoning, one in which rights, universal duties, and categorical obligations are central. Ethics, by contrast, is an older and fuzzier-edged kind of practical thinking. It reflects on the good life more broadly, and it is intimately bound up with the values and self-understandings of concrete historical communities. Contemporary philosophers often take great care to distinguish morality from ethics. Moreover, the philosophers who distinguish these terms usually privilege one over the other, arguing that morality is fundamental and ethics derivative, or vice versa. I have no quarrel with the distinction between morality and ethics. But I want to argue that we cannot and should not choose between them: that the attempt to privilege one of these kinds of thinking over the other is misguided and bound to fail. Morality and ethics, I maintain, are not competing theories of practical

reason but rather complementary and inseparable aspects of our experience as agents. My argument for this claim falls into five parts. After some background, I discuss Bernard Williamss recent attempt to privilege ethics over morality, and argue that it does not succeed. Then I examine Jrgen Habermass claim that morality is more fundamental than ethics, arguing that it too does not succeed. Next, I try to explain why these attempts fail, and propose that we look for some way of not choosing between morality and ethics. Finally, I sketch a way of doing so. My goal here is not to give a fully developed theory of practical reason. I simply want to argue that two popular approaches to practical reasoning will not work, and to make some suggestions about where we might start looking for a new approach. 53 THE PHILOSOPHICAL FORUM Volume XXXII, No. 1, Spring 2001 I The distinction between morality and ethics seems to derive from Hegel. At many points in his work, Hegel distinguishes two sorts of practical reasoning: one grounded in what he calls Sittlichkeit, the other in what he calls Moralitt.

Sittlichkeitusually translated as ethical substance or ethical life is associated with Greek practical reasoning.1 It is the ethical life of a nation in so far as it is the immediate truththe individual that is a world.2 A Sittlichkeit is a concrete historical community with a shared way of life. It has its own conceptions of duties, virtues, and the good, conceptions which are taken for granted in this community but which need not be accepted in others. From this standpoint, to be a good agent is to be a good member of ones Sittlichkeitto know ones station and ones duties. Opposed to this is a view of practical reason grounded in Moralitt. Hegel generally uses this term as a synonym for Kantian morality. The moral standpoint knows duty to be the absolute essence.3 It insists that the duties which bind agents have nothing to do with the ethical understandings of particular communitiesor, for that matter, with anything in the phenomenal realm. Pure reason gives a moral law to itself, and this law obliges categorically. It is valid at all times and all places, not just in some particular ethical community. Thus for Hegel, there are two ways of thinking about practical reason. One

sees it as context-bound and community-based; the other sees it as universal and categorical. One focuses on what is considered good by some community or other; the other focuses on what is right independently of any community. In short, one deals with the ethical, the other with the moral. I am not suggesting that Hegels distinction between Sittlichkeit and Moralitt maps exactly onto the contemporary distinction between ethics and morality. Clearly, however, Hegel paves the way for such a distinction. During the past thirty years or so, philosophers of many different stripes have appealed to just this distinction. It appears in at least three contemporary discussions. First, it has surfaced in Anglo-American political philosophy, in the guise of a debate between liberals and communitarians. Liberals do not want the state to endorse any particular view of the good life; they simply want it to enforce a minimal code of right conduct.4 Communitarians reject the liberal conception of the state in favor of one with a richer and more historically specific view of the good.5 Liberals, we might say, want the state to be in the morality business, while communitarians want it to be in the ethics business. A similar debate has

taken place in continental philosophy between self-described neoKantians and neo-Hegelians. The former, such as Karl-Otto Apel, argue that philosophical ethics need not and should not appeal to the intuitions of particular communities. Apels discourse ethics places itself above all such communities and claims to 54 ROBERT PIERCEY be able to adjudicate them.6 Neo-Hegelians, such as Hans-Georg Gadamer, argue that this strategy cannot work, and favor the model of a situationally sensitive practical reason, always functioning against the background of the shared ethical understanding of a community.7 And on both sides of the channel, defenders and critics of philosophical modernity are also divided by their views of morality and ethics. Champions of modernity such as Jrgen Habermas praise its cosmopolitanism and moral universalism.8 Anti-modernists such as Alasdair MacIntyre condemn modernity as morally bankrupt, and yearn for local forms of community within which the moral life can be sustained through the new dark ages which are already upon us.9 With all this intellectual firepower assembled for and against morality and ethics, one might take it for granted that the two are simply opposed, and that

there is nothing left to do but choose between them. Indeed, this view usually is taken for granted. But I think this view is mistaken, and I think the best way to show this is to look closely at some attempts to choose between the ethical and the moral. Let me now turn to the very influential one undertaken by Bernard Williams. II Williams begins Ethics and the Limits of Philosophy with a deliberately vague description of ethical thinking. The ethical is a unique but fuzzyedged kind of practical thinking, one that makes special demands on agents but that cannot be precisely defined. About the only general characteristic of ethical thinking is that it is concerned with what Williams calls Socratess questionnamely, How should one live?10 This is a perfectly general question. It assumes that something relevant or useful can be said to anyone, in general, about how to live; and it takes less for granted than questions such as What is our duty? or How may we be good?11 Many different considerations might be relevant to the question of how one ought to live. Williams thinks we naturally use a variety of different

ethical considerations, which are genuinely different from one another, and moreover that this is what one would expect to find.12 This is all very vague, of course, and Williams does not suggest that we might systematically catalogue all ethical notions. Still, he believes we have an intuitive though vague understanding of what ethical thinking is. It is a multifaceted and extremely general reflection on the good life. Such reflection, Williams insists, is quite different from what he calls moral thinking. He claims that the word morality has by now taken on a distinctive content that sets it apart from ethical reflection considered more broadly. Williams sees morality as a particular development of the ethical, a newcomer whose history is both relatively short and of special significance in Western 55 MORALITY AND ETHICS culture.13 The rise of morality is closely related to processes of modernization 14 of the last five centuries. It has something to do with the Reformation and its understanding of the individuals responsibility before God. It also has something to do with the scientific revolution and the subsequent demise of Aristotelianism. Above all, the rise of morality is a result of the modern worlds

drive toward a rationalistic conception of rationalityits demand that practical reason mimic theoretical reason, and be judged by the same standards. In Williamss view, modernity requires every decision to be based on grounds that can be discursively explained.15 Applying this ideal to ethical thinking yields morality. Far from being synonymous with ethics, morality is a peculiar institution16 with an even more peculiar genealogy. So what distinguishes morality from ethics? Briefly, Williams claims that morality peculiarly emphasizes certain ethical notions rather than others, and also has some peculiar presuppositions.17 These presuppositions are many. It has an unusual view of moral language, and demands a sharp boundary for itself (in demanding moral and nonmoral senses of words, for instance). It also has a peculiar view of autonomyit insists that all genuine ethical considerations rest, ultimately and at a deep level, in the agents will.18 Most importantly, however, morality has a peculiar understanding of obligation. And it gives obligation a much more central role than do other kinds of ethical thinking. Williams does not claim that obligation as such is unique to the moral. He grants

that obligations are among the most basic of ethical considerations, and that they play a role in, for instance, Aristotelian ethics. Williamss quarrel is with the peculiar kind of obligation at work in moral thinking. But what kind is that? In Williamss view, morality sees obligation as categorical.19 It has a third-personal20 understanding of obligations and duties. Morality believes that obligations are unconditional and inescapable, that they go all the way down. One sign of this is the Kantian dictum that ought implies canthe belief that if an action is ethically appropriate, then it is something I am categorically required to do, and something it is in my power to do. As Williams puts it, if my deliberation issues in something I cannot do, then I must deliberate again.21 Closely related to this is the conviction that moral obligations . . . cannot conflict, ultimately, really, or at the end of the line.22 Unlike, say, Greek ethics, morality denies the possibility of certain kinds of ethical conflict. I cannot, through no fault of my own, end up in situations in which it is impossible for me to be good. Behaving ethically is in no way a function of moral luck. Finally, morality encourages the idea, only an obligation can beat an obligation.23 Moral obligations

have a stringency which makes them overriding. No other ethical considerations can trump them. For the system of morality, obligationsand therefore judgment and blameapply categorically to everyone. They apply even to people who, at the limit, want to live outside that system altogether. From the 56 perspective of morality, there is nowhere outside the system, or at least nowhere for a responsible agent.24 My only excuse for ignoring an obligation is that some more pressing obligation overrides it. Williamss objection to morality is that this view of obligation has absurd consequences. Morality tries to make everything into obligations.25 The only ethical consideration that can trump an obligation is a more general obligation. So whenever an ethical consideration overrides an obligation, the moralist tries to find some duty from which the first consideration can be derived. Consider the textbook example of promise-breaking. Suppose I have entered into an obligation to meet a friend. Suppose further that at the last minute, I am presented with a unique opportunity, at a conflicting time and place, to further some important cause.26 Most moralists would say I am permitted to shirk the obligation

to visit my friend and further the cause. But why? If moral obligations are categorical, how can I possibly get out of one? The only answer, it seems, is that by furthering the cause in question, I am acting in accordance with some other, more general obligation, something along the lines of Always further important causes when given the chance. This seems to imply that I am always under a variety of exceedingly vague obligations. But Williams argues that once the journey into more general obligations has started, we may begin to get into troublenot just philosophical trouble, but conscience troublewith finding room for morally indifferent actions. It seems obvious that some actions are of no moral consequence at all. But if I am always under exceedingly general obligations such as Always further important causes when given the chance, then how can I ever be permitted to act in morally indifferent ways? Am I not obliged, categorically obliged, to forego all morally neutral actions so that I may obey my general duties? Is it not the case that obligations are always waiting to provide work for idle hands?27 The point is that if obligation is allowed to structure ethical thought, . . . it

can come to dominate life altogether.28 And to let obligations dominate life is to create not just philosophical trouble, but conscience trouble. Thus the view of obligation found in morality is unacceptable. It is the systems reductio ad absurdum. The only response to this reductio is to abandon morality altogether not in order to become ethical nihilists, but to replace morality with a more subtle and more flexible style of ethical thinking. But what would become of Williamss project if it turned out that ethical reflection and moral obligation are not separable in the way he suggests? Of course the two are distinguishable; if they were not, it would be impossible to write about them in the way Williams and I have done. But suppose one argued that all ethical reflection, as such, is subject to something like moral obligations. If one were successful at this, it would reveal a fatal flaw in Williamss position. Morality would be indispensable to ethics, and Williamss critique of morality 57 would have to be re-evaluated or rejected. So let me now turn to one such argument: the one given by Paul Ricoeur in Oneself as Another. The dispute between Ricoeur and Williams would be uninteresting if it were

merely verbal. So it cannot be the case that Williams defines morality as one thing, which turns out to be separable from ethical reflection, while Ricoeur defines it as something else, which turns out to be indispensable. On the contrary, Ricoeur uses the terms ethics and morality in the same way Williams does. By ethics, Ricoeur understands a vague and fuzzy-edged kind of practical thinking concerned with the good life. He says that it is by convention that I reserve the term ethics for the aim of an accomplished lifethat is, for reflections on how one ought to live. Similarly, like Williams, Ricoeur denies that morality is identical with ethics. Morality is only a limited . . . actualization of the ethical, a particular development of ethical reflection considered more broadly. This development is concerned with norms characterized at once by the claim to universality and by an effect of constraint. Universal norms characterized by constraint: these look very much like Williamss third-personal, categorical obligations. Further proof that Ricoeur associates the moral with categorical duties is his explicit appeal to Kant in defining morality. Moral norms, he argues, are bound up with a Kantian heritage and with its deontological point of view.29 Williams, I think, would agree with all of this. So the

disagreement between Williams and Ricoeur is more than a verbal one. They give equally precise definitions of morality, and equally fuzzy-edged definitions of ethics. Unlike Williams, however, Ricoeur does not think that the definition of ethics needs to remain quite so fuzzy-edged. He argues that once we reflect on the nature of ethical thinkingthat is, on thinking about the good lifewe can see that there are certain purely logical constraints on its subject matter. Comprehensive ethical thinking must involve certain features, or cease to be ethical thinking. This is neither a purely semantic point nor some sort of transcendental deduction about ethical experience. It is somewhere between the two. To take a more familiar example, it is something like the claim Philippa Foot advances in her well-known paper, Moral Beliefs. Foot argues that certain attitudes and beliefs have an internal relation to their objects. Pride, for example, is one of these. To understand the definition of pride is to see that we can be proud only of certain thingsnamely, of achievements or advantages that are in some way our own.30 Foot believes that the terms good and right bear the same relation

to good things and right actions. To understand what good means is to see that there are certain purely logical constraints on what things we can call good. Ricoeurs point, I take it, is similar to Foots. Once we understand the definition of ethicsno matter how fuzzy-edged it may bewe see that there are certain features any complete ethical inquiry must have. Once we know what it means 58 ROBERT PIERCEY to reflect on the good life, we see that any such reflection has to have certain features. But what features? Ricoeur outlines three. Following Aristotle, he claims that ethics necessarily involves aiming at the good life, with and for others, in just institutions.31 Let me break this formula into its components. The first means, roughly, that one cannot just reflect on the good life; one must also reflect on the good life. Consistent ethical thinking has to involve structured reflection on ones life as a wholeon ones goals, projects, and so on. This is not necessarily to saywith MacIntyre, for instancethat one must conceive of ones life as a teleologically structured, narrative unity. It is merely to say that any answer to Socratess

question will involve an implicit or explicit conception of the good. To be an ethical agent is to give oneself a life plan, a broader unity in which particular actions can be integrated.32 The second part of Ricoeurs formula means that to aim for the good life is to do so with and for others. To reflect on ethics is to see the necessity of certain interpersonal relations, the totality of which Ricoeur calls solicitude.33 More specifically, Ricoeur argues with Aristotle that friendship is necessary for the good life. One cannot aim for a good life all alone; one needs to relate to other selves who have the role of providing what one is incapable of providing for oneself.34 Finally, to pursue the good life is to do so in just institutions. The thought here is that humans are social and historical creatures, and that any complete answer to Socratess question will make reference to organized ways of living together as this belongs to a historical community. 35 In short, Ricoeur thinks that without too much difficulty, we can flesh out our fuzzy-edged intuitions about ethical reflection. At a minimum, our reflections on the good life should say something about forming life plans, relating to other selves, and participating in social and political institutions. These activities

are essential parts of ethical thought. Next, Ricoeur argues that there are certain obvious ways in which each of these activities can go wrong. This does not mean do wrong things, where wrong is a term of moral disapproval. Ricoeurs point is that these activities can be carried out in such corrupt, misguided ways that we would no longer recognize them as the activities they are. Note again the parallel to Philippa Foots work. Just as Foot argues there are some objects to which the terms good and pride cannot conceivably be applied, Ricoeur thinks there are some activities that ethical reflection cannot possibly involve, without ceasing to be ethical reflection. Certain answers to Socratess question can just be ruled out of court. And this is true at each level of Ricoeurs analysis. At the first level, when one pursues the good life by forming a life plan, one cannot knowingly give oneself an evil life plan. There is no need to give content to the notion of evil here. It is sufficient to note that no agent who understands what the good life is will think one can achieve it by following an evil life plan. Second, to strive for the good 59 MORALITY AND ETHICS

life with and for others is to see the impossibility of relating to others in certain ways. Again, there is no need to give content to this idea just yet. But clearly, solicitude and friendship can be corrupted in such extreme ways that they cease to be solicitude and friendship. To deny this is to misunderstand what solicitude and friendship are. Finally, if humans are social creatures who seek the good life in historical communities, then there are certain kinds of communities that any agent would recognize as ethically unacceptable. These are institutions that do not allow the agent to pursue the good lifethat is, institutions that are unjust. Like evil life plans and the improper treatment of others, they are blatant corruptions of the ethical. The only way to avoid corruption of this sort, Ricoeur argues, is to see even the most general ethical reflection as subject to certain norms. At each level, the ethical intention must pass through the sieve of the norm.36 If it fails to do so, then it lacks a feature that ethical reflection has to have. Ethics turns out to be governed by three highly abstract sets of norms. First, the agent is obliged not to furnish herself with an evil life plan. Because there is evil, Ricoeur argues,

the aim of the good life has to be submitted to the test of the moral obligation, which might be described in the following terms: Act only in accordance with the maxim by which you can at the same time will that what ought not to be, namely evil, will indeed not exist.37 Similar norms arise at the second level, in response to the figures of evil in the intersubjective dimension established by solicitude. For very complicated reasons, Ricoeur thinks these norms will take the form of Levinasian injunctions about the treatment of the other. They will appear as prescriptions and prohibitions stemming from the Golden Rule in accordance with the various compartments of interaction: you shall not steal, you shall not kill, you shall not torture.38 Finally, at the third level, Ricoeur thinks agents are committed to resisting the appearance of radically unjust institutions, institutions which fail to treat agents as autonomous beings with conceptions of the good. Communities must be structured so as to prevent such injustice. At each of the three levels, it is necessary to subject the ethical aim to the test of the norm.39 This test amounts to setting (something) aside, as this will be expressed in each of the three spheres.40

Ricoeurs argument, and my reconstruction of it, are highly abstract, and a great deal more needs to be said about both. But if Ricoeur is right, then even the most general of ethical reflection is subject to certain norms. Ethical agents, as such, are obliged not to behave in certain ways. To shirk these obligations is to stop being an ethical agent. So Ricoeurs three general norms are not just one type of ethical consideration among others. They are so fundamental that they go all the way down, as it were. They are what Williams would call thirdpersonal or categorical obligations. Of course, there is much more to ethics than these obligations. Ricoeur grants that there are many other ethical considerations, 60 ROBERT PIERCEY including many that are not obligations at all. And of course, Ricoeurs norms are relatively thin and unsubstantial. They resemble nothing so much as Saint Thomass extremely general account of natural law in the Summa Theologiae: Act virtuously, avoid evil, and so on. But the issue is not whether all ethical reflection is subject to substantial norms. It is whether ethics is subject to any

norms that go all the way down. If Ricoeur is right, then at least three of the norms governing action do go all the way down. That is enough to show that moral obligation cannot be abandonedthat morality is an indispensable moment of the ethical. So much, then, for Williamss attempt to privilege ethics over morality. One might conclude that Williams has simply picked the wrong side of the debate that if ethics requires morality, then it must be the moral that is more basic than the ethical, and not the other way around. One might conclude that we should favor the right over the good, the universal over the concrete, the individual over the community. But that would be a mistake. While the defenders of ethics prove to be on shaky ground, the defenders of morality are no better off, as I will now try to show. III I suggested above that the distinction between morality and ethics has figured prominently in recent continental philosophy. More specifically, it is at the heart of a debate between self-described neo-Kantians and neo-Hegelians. One of the most distinguished participants in this debate is Jrgen Habermas. Much of

Habermass recent work is an attempt to articulate a contemporary version of Kants moral philosophya Kantianism for the linguistic turn. Habermas argues that some form of Kantianism is still viable today, and that those who see it as a non-starter are simply mistaken. Until recently, however, there was something of a consensus in continental thought that Kants moral philosophy was a nonstarter, and that Hegels famous critique of it had been entirely successful. If Habermass resurrection of Kant is to be at all plausible, it should respond to this critique. So let me begin my discussion of Habermass neo-Kantianism on this point. Following Habermas, I think Hegel has four distinct objections to Kants moral philosophy.41 First, he objects to the formalism of Kantian ethics. Kant thinks an action is permissible if the maxim on which it is based has an acceptable logical formnamely, the form of universalizablity. According to Hegel, this formalism at the level of theory leads to empty tautologies at the level of practice. Any maxim, he claims, can be given an appropriate form for the purposes of testing.42 Second, Hegel objects to the abstract universalism of Kants ethics. For Kant, an actions rightness is in no way a function of the particular 61

MORALITY AND ETHICS situation in which it is performed. It is right because I can consistently will that it become a universal law. In Hegels view, Kantian moral judgment remains external to individual cases and insensitive to the particular context of a problem in need of solution.43 Third, Hegel criticizes Kant for having nothing to say about how moral norms can be applied in practice. Kant places moral worth solely in the will, and not at all in the consequences of an action. Such a will has its object merely as pure dutyit is unable to see the object and itself realized.44 Habermas calls this problem the impotence of the mere ought.45 Finally, Hegel attacks the self-righteous moral zeal of Kantian ethics. Kants moral agent strives to bring the good into actual existence, if necessary through the sacrifice of individuality. 46 Kantian ethics recommends to the advocates of the moral world view a policy that aims at the actualization of reason and sanctions even immoral deeds if they serve higher ends.47 The result of Kantian ethics turns out to be the absolute freedom and terror of the French revolution. For these reasons, Hegel thinks ethics must be based on something richer and

more concrete than Kants good will. This something is Sittlichkeit. An ethics of Sittlichkeit denies that a supreme moral principle can be described in purely formal terms. An actions moral worth is not just a function of consistent willing or of a maxims logical form. To privilege Sittlichkeit over Moralitt is also to deny that practical reason is universal, as Kant maintains. The moral philosopher cannot pull out of thin air norms that bind all human beingsor perhaps all rational creaturesat all times and all places. At best she can articulate the shared ethical understandings of a concrete community. Basing ethics on Sittlichkeit therefore solves the problem of application which plagues Kantian ethics. We need no longer ask whether a good but impotent noumenal will can do anything moral in practice. For while ethical behavior is not just equated with a groups customs and practices, it is intimately bound up with them and incapable of being defined apart from them. The same holds for Hegels fourth objection. Unlike Kantian ethics, an ethics of Sittlichkeit does not sever moral duty from the formative process of spirit and its concrete historical manifestations.48 Hegels good will is

at home in the world, and need not subordinate the world to itself by any means necessary. Habermas responds to this critique in two ways. First, he claims that Hegels arguments against Kant are simply not as good as they seem. Some do not work at all; some apply only to the particular version of Kantianism that Kant himself articulated. Other, more nuanced versions of Kantian moral theorizing might withstand Hegels objections. Habermas claims that of the four criticisms Hegel levels at Kant, several miss the mark entirely. Such is the case, for instance, with Hegels charge of formalism. Habermas asserts that Hegel was wrong to imply that these principles postulate logical and semantic consistency and nothing 62 else. Though Kantianism defines its supreme moral principle in formal terms, it just does not follow that this principle issues only in tautologies. Kants main goal is not merely to offer a test for logical or semantic consistency. It is to postulate the employment of a substantive moral point of view. This moral point of view, and not the categorical imperative, generates the content of morality. The

philosophers task is not to generate maxims at all, much less tautological ones. It is to pass judgment on the conflicts of action [which] grow out of everyday life.49 Habermas also points out that he rejects much of the metaphysical baggage attached to Kants ethics. He gives up Kants dichotomy between an intelligible realm comprising duty and free will and a phenomenal realm comprising inclinations, subjective motives,50 and so forth. It is this dichotomy, he claims, which gives rise to Hegels objections about the impotence of the mere ought. Having abandoned this metaphysical commitment, Habermas thinks he can avoid one of the standard objections to neo-Kantianism. Habermass second rejoinder to Hegel is more direct. Hegel cannot be right about morality, he argues, because privileging Sittlichkeit over Moralitt leads to unacceptable conclusions. He therefore performs a sort of reductio on Hegels critique. Sittlichkeit is always some particular Sittlichkeit, the shared ethical life of some actual community. But Habermas argues, following Kant, that considerations about how actual communities happen to live are irrelevant to ethics.51 Ones Sittlichkeit is contingent, in that I just happen to be born into some concrete

ethical community rather than another. The mere fact that this Sittlichkeit is mine has nothing to do with its being moral. Some ethical substances are immoral, unjust, evil. So Sittlichkeit is an unsuitable foundation for ethics. Habermas argues that the question What should I do? is answered morally with reference to what one ought to do52not what I ought to do as a participant in some shared ethos. As a result, Habermas draws a sharp distinction between ethical discourse and moral discourse. Ethical questions concern what it is good for me to do, in the sense of what will help me lead a flourishing life. Ethics provides advice concerning the correct conduct of life and the realization of a personal life project.53 It helps me understand who I am, how I relate to my life history and traditions, 54 and what sort of person I would like to become. Moral discourse, on the other hand, aims at agreement concerning the just resolution of a conflict in the realm of norm-regulated action.55 It does so by adopting a universal, impersonal standpointmorality requires that we break with all of the unquestioned truths of an established, concrete ethical life.56 Contra Hegel, Sittlichkeit cannot have

the last word on how we should live. Like Kant, Habermas privileges the universal over the concrete, the right over the good. He privileges morality over ethics. The version of Kantianism which Habermas endorses is, of course, his discourse ethics. And it is a version that Habermas considers immune to Hegels 63 MORALITY AND ETHICS criticisms. Kants main insight, in Habermass view, is that morally acceptable norms must be universalizable. Ethics is not practical anthropology; the moral philosopher cannot move from premises about how actual communities behave to conclusions about how one ought to behave. Only universalizability makes a norm acceptable. Habermas, however, does not define a universalizable norm as one capable of being willed by any agent whatsoever. Instead, Habermass discourse ethics bases universalizability on language. It prefers to view shared understanding about the generalizability of interests as the result of an intersubjectively mounted public discourse.57 Habermas articulates this shift in his universalizability principle, or U: every valid norm has to fulfill the condition that all concerned can accept the consequences and the side effects its universal

observance can be anticipated to have for the satisfaction of everyones interests (and that these consequences are preferred to those of known alternative possibilities for regulation). Habermas sees U as a presupposition of intersubjective discourse. Anyone who engages in discourse, he claims, implicitly accepts this principle. Thus to participate in discourse and violate U is to be caught in a performative contradiction.58 Uwhich Habermas explicitly calls a reformulation of the categorical imperative59preserves the main insight of Kantian moral philosophy. At the same time, U is not vulnerable to charges of abstract universalism or practical impotence. For Habermas, discourse is not a procedure for generating justified norms but a procedure for testing the validity of norms that are being proposed and hypothetically considered for adoption.60 While Moralitt is prior to customary ethical life, it is always embedded in what Hegel called Sittlichkeit.61 In other words, discourse ethics is dependent upon contingent content being fed into it from outside,62 some of which is ultimately discarded as being not susceptible to consensus.63 It does not try to generate substantial moral norms, which might be vulnerable to charges of abstract universalism or practical

impotence. Discourse ethics offers only a testing procedure. Still, the shared ethical norms of concrete communities must justify themselves through this testing procedure. We cannot dispense with Sittlichkeit. But Sittlichkeit must justify itself before the tribunal of Moralitt. It should now be clear why Habermas is an important participant in the debate between morality and ethics. His critique of Hegel amounts to a denial of the primacy of ethical thinking. It is a denial that practical reasoning should start with the self-understandings of actual communities. And his claim that Moralitt is prior to Sittlichkeit is an attempt to privilege morality over ethics. But is this attempt successful? Does it vindicate Kant over Hegel, the right over the good, once and for all? I have my doubts. For Habermas, the ethical sphere includes all considerations concerning an established, concrete ethical life,64 all considerations involving the context of a 64 ROBERT PIERCEY particular self-understanding.65 The moral standpoint, by contrast, is expressed by Uby the ability of certain norms to be accepted by all participants in a

practical discourse. Morality tests the content that it receives from some ethical life or other, but one need not participate in any particular ethical life to be moral. Our ability to behave morally consists solely in our ability to apply U and abide with its consequences. This last claim seems indefensible to me. It seems clear to me that applying U at all, and therefore taking up the moral standpoint at all, requires the cultivation of certain virtues. Virtues are character traits which dispose one to act in certain ways, and they emerge only through very specific processes of ethical education. If any practical considerations are embedded in the context of a particular self-understanding,66 surely the virtues are. But if, as I am suggesting, participants in discourse need certain virtues even to use U, then being moral cannot be wholly independent of any particular Sittlichkeit. Being moral is, at least in part, a function of having undergone a particular kind of socialization. And it seems to me that Habermass account of morality is parasitic on certain virtues, for two reasons. The first way in which Habermasian morality requires an account of the virtues has to do with the problem of application. U, it will be recalled, does nothing

but test moral norms. It determines whether a proposed norm is universalizable and thus morally acceptable. But any Kantian would admit that norms are not enough. We need to apply themthat is, we need to know how to go about acting on them. How does one apply the norms which U reveals as acceptable? Habermas admits that this principle cannot regulate problems concerning its own application. The application of rules requires a practical prudence that is prior to the practical reason that discourse ethics explicates. But what is this prudence? Habermas says that it is not subject to the rules of discourse.67 How does it arise, then? How does one become a Habermasian phronemos? The only possible answer seems to be that one acquires the ability to apply norms well in the same way one acquires other virtuesnamely, by undergoing a highly specific moral education in a highly specific kind of community. Being able to apply norms is partially a function of belonging to a highly specific Sittlichkeit. But if this is so, then it seems that Moralitt cannot be prior to Sittlichkeit. There can be no procedure for testing moral norms which is completely separate from

any shared ethical understanding. Moralitt requires Sittlichkeit. Agents can be moral only if they have the good fortune of belonging to a certain kind of ethical community. Habermas is not unaware of this difficulty. He has tried to respond to the objection that practical reason may be forced to abdicate in favor of a faculty of judgment when it comes to applying justified norms to specific cases. Indeed, he does not consider this objection at all damaging to his work. Discourse ethics, Habermas says, can handle this difficulty.68 His argument is that while 65 application is indispensable, this indispensability is not itself a moral matter. Norms obviously need to be applied, and procedures need to be carried out. But this is a matter posterior to moral theory. Application does not enter into the contents of moral norms and procedures, so a sharp distinction between the moral and the ethical can be maintained. In this respect moral norms are like legal ones. Laws need to be enforced, but questions of enforcement presumably come after questions of articulating and justifying the law. They have nothing to

do with whether a given law is coherent or just. Habermas argues that moral norms are no different in this respect. They must be applied, but their application is not a distinctively moral matter. Accordingly, it is not a matter with which the moral theorist need be concerned. This view of norms seems untenable to me. My claim, unlike Habermass, is not merely that norms must be applied if they are to have any effect on our practices. My claim is a stronger one: that application enters into the individuation of norms and procedures themselves, in such a way that it is impossible to state these norms coherently without making some reference to how they will be applied. I am not advancing the trivial thesis that there is a difference between recognizing a norm as valid and putting it into practice. Rather, I am arguing that the way in which a norm is applied enters into the norms content. As a result, Habermas cannot claim that problems of application do not concern the moral theorist. Those who doubt this would do well to remember Wittgensteins discussion of following a rule in the Philosphical Investigations. The lesson of the rule-following considerations, it seems to me, is that there are two different ways

of understanding normatively structured behavior. One is to see it as the enactment of a linguistically stated rule, which remains external to the behavior itself. On this view, someone who counts 2, 4, 6, 8 . . . is best described as following the rule Add 2. Wittgenstein shows that this understanding of normatively structured behavior must be wrong, because an indefinite number of types of behavior fall under any such description. Someone who describes the series 2, 4, 6, 8 . . . as an instance of Add 2 has no way of knowing whether the person counting will continue with 10, 12, 14 . . . or with 15, 23, 37. . . . In other words, if we see a norm as wholly separate from its application, we have no way of individuating norms from one another. Clearly, however, we do individuate norms. How? In a word, through practice. Although our understanding of the norms governing behavior cannot be captured linguistically, it can be exhibited in what we call obeying the rule and going against it in actual cases.69 To see a norm in action is to gain a nondiscursive understanding of how to obey it or go against it. And this is the only way of doing so. No linguistic description of normatively structured behavior is sufficient

to individuate the norms in question from others. To articulate a norm just is to know how it works in practice. But if this is the case, then we cannot 66 ROBERT PIERCEY accept Habermass claim that application is not essential to the moral. Rather, application enters into the content of moral norms and procedures. U is no different from other norms in this respect. We cannot even state it coherently without making some referenceno matter now veiled and intuitiveto how it is applied. So Habermass attempt to separate moral procedures from concerns about prudence and virtue is bound to fail. Highly specific virtues are already at work when we do so much as state a norm. Once we concede this point, it becomes apparent that the virtues are at work elsewhere in Habermass moral theory as well. Consider that Habermas defines morality in terms of discourse. But surely one needs certain virtues to be able to participate in discourse at all. Not just any agent who talks counts as a participant in discourseonly certain kinds of agents do. To take a simple example, one needs to be a good listener. Among other things, this means one must have

the ability to empathize with others, the skill of taking on the perspective of other participants in discourse. One must also possess a certain moral imagination, an ability to visualize what it would be like for proposed norms to be adopted. If someone lacked these virtues, we would not, it seems to me, even recognize her as a participant in discourse. In knowing what it means to participate in discourse, we have already appealed to some sort of account of the virtues. I suspect that we could find many similar examples throughout discourse ethics. Thus we cannot accept Habermass claim that the moral is independent of the ethical. Morality presupposes ethics. IV We now face a peculiar antinomy. On the one hand, Williamss attempt to privilege the ethical over the moral seems bound to fail. Ricoeur is right: there are categorical, unconditional restrictions on the content of ethics, restrictions that can only be called moral ones. The very idea of an ethical understanding that has not passed through the sieve of the moral norm is simply incoherent. Ethics requires morality. But on the other hand, Habermass attempt to privilege morality over ethics also seems bound to fail. There are no moral norms, and no

procedures for testing moral norms, that are absolutely prior to every ethical community. Norms and procedures are vacuous. We cannot even state them without making some reference to how they will be applied, and this application involves highly specific virtues and processes of ethical education. So while ethics presupposes morality, morality also presupposes ethics. Having seen this, should we continue to try and choose between the ethical and the moral? Should we continue to see one term as primary and the other as a derivative, debased moment of it? That would be a peculiar suggestion. As I have suggested, there are equally compelling arguments on both sides of the 67 debate. Nor is the problem a merely epistemic one. It is not just that we do not know how to decide which of the terms is primary and which derivative. It rather seems that in principle, there is no way to privilege one over the other, because each needs the other in order to be what it is. As Ricoeur argues, an ethical standpoint that ignores the categorical injunction against evil life plans and unjust institutions is simply not an ethical standpoint. We can no more seek the

good under such conditions than we can feel pride for achievements that are not in some way our own. Likewise, a morality that has not emerged from some particular Sittlichkeit and that can be applied without highly specific virtues is simply not a morality. Ethics and morality are intimately bound up with one anothernot just in our way of thinking about them, but in their very essence. We can distinguish them in a philosophical analysis, but we cannot separate them enough to choose between them. Why not? The answer, it seems to me, is that ethics and morality are not simply opposed. They should not be seen as competing theories about our experience as agents. They are better understood as moments or aspects of that experience abstract moments that we can distinguish philosophically but cannot separate in practice. And the reason we cannot so separate them is that our experience as agents is just too complex to be reduced to one or the other. This experience is at once ethical and moral, and more besides. We must, I suspect, take it as a brute fact that we find ourselves bound by a wide variety of competing practical considerations. While there are family resemblances among them while we can,

for instance, label some of them ethical and others moralthere is no reason to think we might systematically catalogue them all or reduce them to one of their instances. Our experience is just too complex for that. If we are to make any progress in practical philosophy, we must, it seems to me, begin by preserving the fullness, the diversity, and the irreducibility70 of our experience as agents. Indeed, the most striking similarity between Williams and Habermas is their willingness to marginalize the fullness, diversity, and richness of our moral and ethical experience. Neither seems particularly concerned with how human beings actually lead their lives. Each seems more interested in reductionistic theoretical categories than in subtle moral phenomenology. It is telling that while Williams and Habermas both have their moral heroes, these heroes are remarkable for their lack of humanity. Williams praises Gauguin, who fled to Tahiti after shirking obligations that most of us would consider very real.71 Habermas celebrates the disengaged moral judge who can apply U to practices as though completely detached from them. Naturally, these figures embody aspects of our experience as agents, and to that extent they are useful thought experiments. But

they do not live through moral and ethical experiences that are anything like those of real agents, and this may be a sign that something is amiss. I am not suggesting that common sense and everyday experience are philosophys final 68 ROBERT PIERCEY court of appeal. But I am suggesting that one of the tasks of philosophy is to make sense of our experience as agents. If a moral or ethical theory does not mesh with this experience at all, if it is entirely unresponsive to moral phenomenology, then perhaps something has gone wrong. If ethics and morality are what I am suggesting they arethat is, complementary aspects of our irreducibly complex experience as agentsthen the attempt to choose between them is doomed from the start. Perhaps, then, we should try to find a way of not choosing between them. Perhaps instead of making one prior to the other, we should look for a way of thinking the two together. No doubt there are several ways of doing so. What follows is a sketch of one. And, like many of the good things in life, it involves going back to Hegel. V The contrast between morality and ethics is usually seen as a contrast between

the universal and the particular. Morality is used as a synonym for any universalistic view of practical reason, ethics as a synonym for any view of practical reason as community-based. This distinction is often thought to be rooted in Hegels distinction between Moralitt and Sittlichkeit. But it is important to point out that this is not Hegels understanding of Sittlichkeit. For Hegel, an ethics of Sittlichkeit is not just any ethic which sees practical reason as contextbound. In the Philosophy of Right and the Phenomenology of Spirit, Hegel uses Sittlichkeit to refer to a synthesis between the universal and the particular. The view of practical reason usually called neo-Hegelian today is one that Hegel places at the level of abstract right. This levelwhere one sees moral obligations as the immediate concept and hence also essentially individual72is beneath both Moralitt and Sittlichkeit. At the level of Sittlichkeit, agents do not just deliberate about particular situations, which are opposed to more universal moral concerns. Sittlichkeit is rather the unity and truth of these two abstract momentsthe thought Idea of the good realized in the internally reflected will and in the external

world.73 A Sittlichkeit is a special kind of ethical community, one which embodies a universalistic moral standpoint in a particular community. It is not just a concrete ethical life, but a concrete ethical life with a rational and moral structure. Perhaps it would be fruitful to follow Hegel here. Perhaps it would be useful to think of moral communities as Hegel doesnot as brutely given ethical substances, but as syntheses of the universal and the concrete. Perhaps seeing this kind of ethical community as fundamental will allow us to avoid choosing between the abstract senses of Moralitt and Sittlichkeit, and to avoid having to choose between morality and ethics. 69 MORALITY AND ETHICS This suggestion is bound to seem absurd at best and offensive at worst. How, we might ask, could one regard concrete ethical communities as Hegel does as particular ethical substances which embody universal moral principles? No thinking person sees our political and cultural institutions as rationally structured and morally benevolent. Nor should we have any faith that they are progressing

and so becoming ever more rational, ever more benevolent. So even if Hegel understands Sittlichkeit as a union of universal and particular ethical principles, we have no reason to understand it in that way. This last claim, however, strikes me as a non sequitur. Of course it would be absurd to suggest that the institutions of Western liberal democracy, as given, are both rationally structured and morally benevolent. It would be equally absurd to suggest that they are becoming so on their own. But suppose one saw Hegelian Sittlichkeit not as something given, but as a task to be achieved. Suppose one saw it as an ideal to be realized, or at least approximated. Suppose further that one saw the realization of this ideal as a task not for philosophy, but for politics. Perhaps this sort of ethical substance would be an appropriate moral category, and a moral category that can help us overcome a dichotomy which cripples much contemporary philosophy. Moreover, there is some precedent in contemporary philosophy for understanding Sittlichkeit along these lines. Consider Habermass view of the ideal speech situation. Habermas presents it as a regulative ideal that we must use when thinking about discourse. It has never existed anywhere, nor could it ever

exist. But if we discover that a discourse has been conducted under less than ideal situations, its outcome is to that extent invalidated. And the onus is on us to change that speech situation, to make it a closer approximation of the ideal. Granted, Habermas has recently cautioned against seeing the ideal speech situation as a goal to be reached through practice.74 But it might be fruitful to think of moral and political communities in this wayas concrete ethical substances which ought to have ideally rational and moral structures. And to the extent that they fall short of this ideal, the onus is on us to change them. Philosophers cannot do this on their own. It is a political task, and it can only be achieved through political practice. There are unanswered questions here, of course. What sort of political action is appropriate here? What sort of rationality, and what sort of universality, should our institutions embody? Whose rationality, and whose morality, are at issue? I do not have answers to any of these questions. Nor do I think philosophers should answer them. If philosophy cannot choose between morality and ethics on its own, then neither can it bring the two together on its own. Perhaps all that philosophy

can do is make the world safe for politics. University of Notre Dame 70 ROBERT PIERCEY NOTES 1 See, for instance, Hegel, Phenomenology of Spirit, trans. A.V. Miller (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977), 26694. 2 Hegel, Phenomenology, 265. 3 Hegel, Phenomenology, 365. 4 The definitive contemporary statement of this view is, of course, John Rawls, A Theory of Justice (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1971). 5 See, for instance, Michael Sandel, Liberalism and the Limits of Justice (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982). 6 See Karl-Otto Apel, Is the Ethics of the Ideal Communication Community a Utopia? On the Relationship between Ethics, Utopia, and the Critique of Utopia, in The Communicative Ethics Controversy, ed. Seyla Benhabib and Fred Dallmayr (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1990). 7 Seyla Benhabib, Afterword: Communicative Ethics and Contemporary Practical Philosophy, in The Communicative Ethics Controversy, 333. 8 See, for instance, Jrgen Habermas, The Philosophical Discourse of Modernity, trans. Frederick Lawrence (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1987). 9 Alasdair MacIntyre, After Virtue, 2nd ed. (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1984), 263.

10 Bernard Williams, Ethics and the Limits of Philosophy (London: Fontana, 1985), 4. 11 Williams, Ethics, 4. 12 Williams, Ethics, 16. 13 Williams, Ethics, 6. 14 Williams, Ethics, 8. 15 Williams, Ethics, 18. 16 Williams, Ethics, 174. 17 Williams, Ethics, 6. 18 Williams, Ethics, 7. 19 Williams, Ethics, 178. 20 Williams, Ethics, 177. 21 Williams, Ethics, 175. 22 Williams, Ethics, 176. 23 Williams, Ethics, 180. 24 Williams, Ethics, 178. 25 Williams, Ethics, 180. 26 Williams, Ethics, 180. 27 Williams, Ethics, 181. 28 Williams, Ethics, 182. 29 Paul Ricoeur, Oneself as Another, trans. Kathleen Blamey (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992), 170. 30 Philippa Foot, Moral Beliefs, in Twentieth Century Ethical Theory, ed. Steven M. Cahn and Joram G. Haber (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1995), 367. 31 Ricoeur, Oneself as Another, 172. 32 Ricoeur, Oneself as Another, 178. 33 Ricoeur, Oneself as Another, 180. 34 Ricoeur, Oneself as Another, 185. 35 Ricoeur, Oneself as Another, 194.

36 Ricoeur, Oneself as Another, 170. 71 MORALITY AND ETHICS 37 Ricoeur, Oneself as Another, 218. 38 Ricoeur, Oneself as Another, 221. 39 Ricoeur, Oneself as Another, 204. 40 Ricoeur, Oneself as Another, 221. 41 Habermas lays out these objections in Morality and Ethical Life: Does Hegels Critique of Kant Apply to Discourse Ethics? which appears in Habermas, Moral Consciousness and Communicative Action, trans. Christian Lenhardt and Shierry Weber Nicholsen (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1990). 42 See Hegel, Phenomenology, 36574. 43 Habermas, Morality and Ethical Life, 195. 44 Hegel, Phenomenology, 366. 45 Habermas, Morality and Ethical Life, 196. 46 Hegel, Phenomenology, 233. 47 Habermas, Morality and Ethical Life, 196. 48 Habermas, Morality and Ethical Life, 196. 49 Habermas, Morality and Ethical Life, 204. 50 Habermas, Morality and Ethical Life, 203. 51 Habermas argues this in On the Pragmatic, the Ethical, and the Moral Employments of Practical Reason, in Habermas, Justification and Application, trans. Ciaran P. Cronin (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1993). 52 Habermas, Moral Employments of Practical Reason, 8. 53 Habermas, Moral Employments of Practical Reason, 9. 54 Habermas, Moral Employments of Practical Reason, 5.

55 Habermas, Moral Employments of Practical Reason, 9. 56 Habermas, Moral Employments of Practical Reason, 12. 57 Habermas, Morality and Ethical Life, 203. 58 Jrgen Habermas, Discourse Ethics: Notes on a Program of Philosophical Justification, in The Communicative Ethics Controversy, 6970. 59 Habermas, Discourse Ethics, 72. 60 Habermas, Discourse Ethics, 100. 61 Habermas, Discourse Ethics, 96. 62 Habermas, Discourse Ethics, 100. 63 Habermas, Discourse Ethics, 101. 64 Habermas, Moral Employments of Practical Reason, 12. 65 Habermas, Moral Employments of Practical Reason, 4. 66 Habermas, Moral Employments of Practical Reason, 4. 67 Habermas, Discourse Ethics, 101. 68 Habermas, Morality and Ethical Life, 210. 69 Ludwig Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations, trans. G. E. M. Anscombe (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1953), 81. 70 Paul Ricoeur, On Interpretation, in Ricoeur, From Text to Action, trans. Kathleen Blamey and John B. Thompson (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991), 2. 71 Bernard Williams, Moral Luck, in Williams, Moral Luck (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981), 22. 72 G. W. F. Hegel, Elements of the Philosophy of Right, trans. H. B. Nisbet, ed. Allen Wood (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 74. 73 Hegel, Philosophy of Right, 62. 74 Jrgen Habermas, Between Facts and Norms: Contributions to a Discourse Theory of Law and

Democracy, trans. William Rehg (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1994), 32223. 72 ROBERT PIERCEY

You might also like

- Human Kindness and the Smell of Warm Croissants: An Introduction to EthicsFrom EverandHuman Kindness and the Smell of Warm Croissants: An Introduction to EthicsNo ratings yet

- Public Morality Refers To: PhilosophyDocument6 pagesPublic Morality Refers To: PhilosophyChristopher AiyapiNo ratings yet

- Moral Relativism & The Evolution of MoralityDocument51 pagesMoral Relativism & The Evolution of Moralitysamu2-4uNo ratings yet

- The Egalitarian Species: Gerald GausDocument44 pagesThe Egalitarian Species: Gerald GausCarlos PlazasNo ratings yet

- Ethical Egoism Vs Cultural Relativism Reflection PaperDocument4 pagesEthical Egoism Vs Cultural Relativism Reflection PaperLisa Marion67% (3)

- Epstein, Ethics Ov Imagination, Transcultural Experiments, 1999Document5 pagesEpstein, Ethics Ov Imagination, Transcultural Experiments, 1999greym111No ratings yet

- Moral RelativismDocument5 pagesMoral RelativismnieotyagiNo ratings yet

- Morality: Could It Have A Source? Was There A Root Before It Flowers?Document13 pagesMorality: Could It Have A Source? Was There A Root Before It Flowers?lhuk banaagNo ratings yet

- Shades of Morality: A Comprehensive Study of Ethics and MoralityFrom EverandShades of Morality: A Comprehensive Study of Ethics and MoralityNo ratings yet

- ETHICS 2022 Ethics Is The Branch of Philosophy That Studies Morality or The Rightness or Wrongness of HumanDocument20 pagesETHICS 2022 Ethics Is The Branch of Philosophy That Studies Morality or The Rightness or Wrongness of HumanJustin LapasandaNo ratings yet

- Morality: Morality (From Latin: MoralitasDocument19 pagesMorality: Morality (From Latin: MoralitasChristopher AiyapiNo ratings yet

- Authority and Autonomy: An Ethical Perspective: Tully HarcsztarkDocument12 pagesAuthority and Autonomy: An Ethical Perspective: Tully Harcsztarkoutdash2No ratings yet

- Morality - WikipediaDocument29 pagesMorality - WikipediaMuhammed SabdatNo ratings yet

- Xim Martinez 17032958Document11 pagesXim Martinez 17032958Xim VergüenzaNo ratings yet

- Virtue Ethics 2Document13 pagesVirtue Ethics 2Vishal SinghNo ratings yet

- Ethical RelativismDocument12 pagesEthical RelativismFarra YanniNo ratings yet

- Ethics and PracticeDocument11 pagesEthics and PracticeStephen TurnerNo ratings yet

- The John Stuart Mill Collection: Works on Philosophy, Politics & Economy (Including Memoirs & Essays)From EverandThe John Stuart Mill Collection: Works on Philosophy, Politics & Economy (Including Memoirs & Essays)No ratings yet

- Cultural Relativism, Ethical Subjectivism & Ethical EgoismDocument12 pagesCultural Relativism, Ethical Subjectivism & Ethical EgoismThalia Sanders100% (1)

- Ethics and the Full-Breasted Richness of Life: A Roycean Approach to Nourishing the Good LifeFrom EverandEthics and the Full-Breasted Richness of Life: A Roycean Approach to Nourishing the Good LifeNo ratings yet

- The Collected Works of John Stuart Mill: Utilitarianism, The Subjection of Women, On Liberty, Principles of Political Economy, A System of Logic, Ratiocinative and Inductive, Memoirs…From EverandThe Collected Works of John Stuart Mill: Utilitarianism, The Subjection of Women, On Liberty, Principles of Political Economy, A System of Logic, Ratiocinative and Inductive, Memoirs…No ratings yet

- A Reader's Guide To The Anthropology of Ethics and Morality - Part II - SomatosphereDocument8 pagesA Reader's Guide To The Anthropology of Ethics and Morality - Part II - SomatosphereECi b2bNo ratings yet

- John Stuart Mill: Collected Works: Utilitarianism, The Subjection of Women, On Liberty, Principles of Political Economy…From EverandJohn Stuart Mill: Collected Works: Utilitarianism, The Subjection of Women, On Liberty, Principles of Political Economy…No ratings yet

- General Ethics - Basic Concepts in EthicsDocument53 pagesGeneral Ethics - Basic Concepts in EthicsRoger Yatan Ibañez Jr.No ratings yet

- Normative EthicsDocument5 pagesNormative Ethicskumesa urgessaNo ratings yet

- Moral Imagination: Implications of Cognitive Science for EthicsFrom EverandMoral Imagination: Implications of Cognitive Science for EthicsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (4)

- Moral Philosophy Thesis IdeasDocument8 pagesMoral Philosophy Thesis IdeasAudrey Britton100% (2)

- What Are Descriptive Ethics?: Explain Various Theories of B.EDocument4 pagesWhat Are Descriptive Ethics?: Explain Various Theories of B.Evj_for_uNo ratings yet

- Reflection On MoralityDocument4 pagesReflection On MoralityCriselda Cabangon DavidNo ratings yet

- The Virtues of Our Vices: A Modest Defense of Gossip, Rudeness, and Other Bad HabitsFrom EverandThe Virtues of Our Vices: A Modest Defense of Gossip, Rudeness, and Other Bad HabitsRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (2)

- Clark, On The Rejection of Morality - Bernard Williams's Debt To NietzscheDocument23 pagesClark, On The Rejection of Morality - Bernard Williams's Debt To NietzschejipnetNo ratings yet

- JOHN STUART MILL - Ultimate Collection: Works on Philosophy, Politics & Economy (Including Memoirs & Essays): Autobiography, Utilitarianism, The Subjection of Women, On Liberty, Principles of Political Economy, A System of Logic, Ratiocinative and Inductive and MoreFrom EverandJOHN STUART MILL - Ultimate Collection: Works on Philosophy, Politics & Economy (Including Memoirs & Essays): Autobiography, Utilitarianism, The Subjection of Women, On Liberty, Principles of Political Economy, A System of Logic, Ratiocinative and Inductive and MoreNo ratings yet

- Ethics without Principles: Another Possible Ethics—Perspectives from Latin AmericaFrom EverandEthics without Principles: Another Possible Ethics—Perspectives from Latin AmericaNo ratings yet

- Normative EthicsDocument3 pagesNormative EthicsPantatNyanehBurik100% (1)

- NBC September 2023 Poll For Release 92423Document24 pagesNBC September 2023 Poll For Release 92423Veronica SilveriNo ratings yet

- Civil Engineering Colleges in PuneDocument6 pagesCivil Engineering Colleges in PuneMIT AOE PuneNo ratings yet

- Consultative Approach Communication SkillsDocument4 pagesConsultative Approach Communication SkillsSadieDollGlonekNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Hospitality Management: Po-Tsang Chen, Hsin-Hui HuDocument8 pagesInternational Journal of Hospitality Management: Po-Tsang Chen, Hsin-Hui HuNihat ÇeşmeciNo ratings yet

- Carnap, R. (1934) - On The Character of Philosophical Problems. Philosophy of Science, Vol. 1, No. 1Document16 pagesCarnap, R. (1934) - On The Character of Philosophical Problems. Philosophy of Science, Vol. 1, No. 1Dúber CelisNo ratings yet

- Practical ResearchDocument3 pagesPractical ResearchMarcos Palaca Jr.No ratings yet

- Makalah Bahasa InggrisDocument2 pagesMakalah Bahasa InggrisDinie AliefyantiNo ratings yet

- Computer Applications in ChemistryDocument16 pagesComputer Applications in ChemistryGanesh NNo ratings yet

- MQ 63392Document130 pagesMQ 63392neeraj goyalNo ratings yet

- Learning and Cognition EssayDocument6 pagesLearning and Cognition Essayapi-427349170No ratings yet

- Marissa Mayer Poor Leader OB Group 2-2Document9 pagesMarissa Mayer Poor Leader OB Group 2-2Allysha TifanyNo ratings yet

- Ps Mar2016 ItmDocument1 pagePs Mar2016 ItmJessie LimNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Map - Math8Document5 pagesCurriculum Map - Math8api-242927075No ratings yet

- Introduction To Research Track 230221Document24 pagesIntroduction To Research Track 230221Bilramzy FakhrianNo ratings yet

- Jinyu Wei Lesson Plan 2Document13 pagesJinyu Wei Lesson Plan 2api-713491982No ratings yet

- Community Health NursingDocument2 pagesCommunity Health NursingApple AlanoNo ratings yet

- Action Plan ReadingDocument7 pagesAction Plan ReadingRaymark sanchaNo ratings yet

- Short Term Studentship 2021 Program Details and Guide For StudentsDocument13 pagesShort Term Studentship 2021 Program Details and Guide For StudentsPrincy paulrajNo ratings yet

- REVIEW of Reza Zia-Ebrahimi's "The Emergence of Iranian Nationalism: Race and The Politics of Dislocation"Document5 pagesREVIEW of Reza Zia-Ebrahimi's "The Emergence of Iranian Nationalism: Race and The Politics of Dislocation"Wahid AzalNo ratings yet

- Regional Ecology Center (REC) GuidelinesDocument48 pagesRegional Ecology Center (REC) GuidelinesKarlou BorjaNo ratings yet

- Original Learning Styles ResearchDocument27 pagesOriginal Learning Styles Researchpremkumar1983No ratings yet

- Jemimah Bogbog - Psych 122 Final RequirementDocument1 pageJemimah Bogbog - Psych 122 Final RequirementJinnie AmbroseNo ratings yet

- Isnt It IronicDocument132 pagesIsnt It IronicNiels Uni DamNo ratings yet

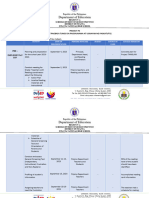

- Department of Education: Solves Problems Involving Permutations and CombinationsDocument2 pagesDepartment of Education: Solves Problems Involving Permutations and CombinationsJohn Gerte PanotesNo ratings yet

- Day 19 Lesson Plan - Theme CWT Pre-Writing 1Document5 pagesDay 19 Lesson Plan - Theme CWT Pre-Writing 1api-484708169No ratings yet

- Samuel Christian College: 8-Emerald Ms. Merijel A. Cudia Mr. Rjhay V. Capatoy Health 8Document7 pagesSamuel Christian College: 8-Emerald Ms. Merijel A. Cudia Mr. Rjhay V. Capatoy Health 8Jetlee EstacionNo ratings yet

- PIT-AR2022 InsidePages NewDocument54 pagesPIT-AR2022 InsidePages NewMaria Francisca SarinoNo ratings yet

- Pestle of South AfricaDocument8 pagesPestle of South AfricaSanket Borhade100% (1)

- Eurocentric RationalityDocument22 pagesEurocentric RationalityEnayde Fernandes Silva DiasNo ratings yet

- Hameroff - Toward A Science of Consciousness II PDFDocument693 pagesHameroff - Toward A Science of Consciousness II PDFtempullybone100% (1)