Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Chipko Movement

Uploaded by

KC G MadhuOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Chipko Movement

Uploaded by

KC G MadhuCopyright:

Available Formats

Chipko movement

The Chipko movement or Chipko Andolan is a movement that practiced the Gandhian methods of satyagraha and non-violent resistance, through the act of hugging trees to protect them from being felled. The modern Chipko movement started in the early 1970s in the Garhwal Himalayas of Uttarakhand, Then in Uttar Pradesh with growing awareness towards rapid deforestation. The landmark event in this struggle took place on March 26, 1974, when a group of peasant women in Reni village, Hemwalghati, in Chamoli district, Uttarakhand, India, acted to

prevent the cutting of trees and reclaim their traditional forest rights that were threatened by the contractor system of the state Forest Department. Their actions inspired hundreds of such actions at the grassroots level throughout the region. By the 1980s the movement had spread throughout India and led to formulation of people-sensitive forest policies, which put a stop to the open felling of trees in regions as far reaching as Vindhyas and the Western Ghats. Today, it is seen as an inspiration and a precursor for Chipko movement of Garhwal. The Chipko movement though primarily a livelihood protection movement rather than a forest conservation movement went on to become a rallying point for many future environmentalists, environmental protests and movements the world over and created a precedent for non-violent protest.[4][5] It occurred at a time when there was hardly any environmental movement in the developing world, and its success meant that the world immediately took notice of this non-violent movement, which was to inspire in time many such eco-groups by helping to slow down the rapid deforestation, expose vested interests, increase ecological awareness, and demonstrate the viability of people power. Above all, it stirred up the existing civil

society in India, which began to address the issues of tribal and marginalized people. So much so that, a quarter of a century later, India Today mentioned the people behind the "forest satyagraha" of the Chipko movement as amongst "100 people who shaped India". Today, beyond the eco-socialism hue, it is being seen increasingly as an ecofeminism movement. Although many of its leaders were men, women were not only its backbone, but also its mainstay, because they were the ones most affected by the rampant deforestation, which led to a lack of firewood and fodder as well as water for drinking and irrigation. Over the years they also became primary stakeholders in a majority of the afforestation work that happened under the Chipko movement. In 1987 the Chipko Movement was awarded the Right Livelihood Award CHIPKO MOVEMENT.

ISSUE

Deforestation is a severe problem in northern India and local people have banded together to preventcommercial timber harvesting. These people have adopted a unique strategy in recognizing trees asvaluable, living beings. The Chipko movement adherents are known literally as "tree huggers."

It was 1973, and the first movement happened spontaneously in a village in the Himalayas. Since then, the Chipko Movement, groups of activists protecting their trees, has spread across Uttar Pradesh and India itself. An active protest, the Chipko Movement put themselves between their beloved trees and the axe threatening to cut them down.

Surviving participants of the first all-woman Chipko action at Reni village in 1974 on left jen wadas, reassembled thirty years later. From 1973, the movement grew rapidly, and in 1980 it succeeded in persuading Indira Gandhi to pass a fifteen year old ban on felling in the Himalayan states. Whats more, although in 2004 one district Himachal Pradesh lifted this ban, in 2005 it was still in place in most districts. He is one of the most prominent leaders of the Chipko movement. An activist and philosopher, between 1981 and 1983 he travelled 5000km across the Himalayas spreading the message of

the Chipkos to those he met. In 1989 he began a series of hunger strikes in protest to dam building in the Himalayas, and the Chipko Movement became the Save the Himalaya Movement. One of the best things about the Chipko Movement was the way it spread to women. In Chamoli district in 1974, a group of women protected 2500 trees from being auctioned off by the government by standing by them. Chipko empowered women to change their world.Weve all heard about tree huggers, but this is one time when this method really worked! It just goes to show that, if you feel strongly about something, if you want to protect it, you can. A Chipko proverb says: Embrace the trees and Save them from being felled; The property of our hills, Save them from being looted. And its true. If you love something, you can fight to save it too, just like the Chipko movement.

History

The Himalayan region had always been exploited for its natural wealth, be it minerals or timber, including under British rule. The end of the nineteenth century saw the implementation of new approaches in forestry, coupled with reservation of

forests for commercial forestry, causing disruption in the age-old symbiotic relationship between the natural environment and the od were crushed severely. Notable protests in 20th century, were that of 1906, followed by the 1921 protest which was linked with the independence movement imbued with Gandhian ideologies, The 1940s was again marked by a series of protests in Tehri Garhwal region. In the post-independence period, when waves of a resurgent India were hitting even the far reaches of India, the landscape of the upper Himalayan region was only slowly changing, and remained largely inaccessible. But all this was to change soon, when an important event in the environmental history of the Garhwal region occurred in the India-China War of 1962, in which India faced heavy losses. Though the region was not involved in the war directly, the government, cautioned by its losses and war casualties, took rapid steps to secure its borders, set up army bases, and build road networks deep into the upper reaches of Garhwal on Indias border with Chinese-ruled Tibet, an area which was until now all but cut off from the rest of the nation. However, with the construction of roads and subsequent developments came mining projects for limestone, magnesium, and potassium. Timber merchants and commercial foresters now had access to land hitherto. Soon, the forest cover started deteriorating at an alarming rate, resulting in hardships for those involved in labour-intensive fodder and firewood collection. This also led to deterioration in the soil conditions, and soil erosion in the area as the water sources dried up in the hills. Water shortages became widespread. Subsequently, communities gave up raising livestock, which added to the problems of malnutrition in the region. This crisis was heightened by the fact that forest conservation policies, like the Indian Forest Act, 1927, traditionally restricted the access of local communities to the forests, resulting in scarce farmlands in an over-

populated and extremely poor area, despite all of its natural wealth. Thus the sharp decline in the local agrarian economy lead to a migration of people into the plains in search of jobs, leaving behind several de-populated villages in the 1960s. Gradually a rising awareness of the ecological crisis, which came from an immediate loss of livelihood caused by it, resulted in the growth of political activism in the region. The year 1964 saw the establishment of Dasholi Gram Swarajya Sangh (DGSS) (Dasholi Society for Village Self-Rule ), set up by Gandhian social worker, Chandi Prasad Bhatt in Gopeshwar, and inspired by Jayaprakash Narayan and the Sarvodaya movement, with an aim to set up small industries using the resources of the forest. Their first project was a small workshop making farm tools for local use. Its name was later changed to Dasholi Gram Swarajya Sangh (DGSS) from the original Dasholi Gram Swarajya Mandal (DGSM) in the 1980s. Here they had to face restrictive forest policies, a hangover of colonial era still prevalent, as well as the "contractor system", in which these pieces of forest land were commodified and auctioned to big contractors, usually from the plains, who brought along their own skilled and semi-skilled laborers, leaving only the menial jobs like hauling rocks for the hill people, and paying them next to nothing. On the other hand, the hill regions saw an influx of more people from the outside, which only added to the already strained ecological balance.[15] Hastened by increasing hardships, the Garhwal Himalayas soon became the centre for a rising ecological awareness of how reckless deforestation had denuded much of the forest cover, resulting in the devastating Alaknanda River floods of July 1970, when a major landslide blocked the river and affected an area starting from Hanumanchatti, near Badrinath to 350 km downstream till Haridwar, further numerous villages, bridges and roads were washed away. Thereafter, incidences of

landslides and land subsidence became common in an area which was experiencing a rapid increase in civil engineering projects.[16][17] "Maatu hamru, paani hamru, hamra hi chhan yi baun bhi... Pitron na lagai baun, hamunahi ta bachon bhi" Soil ours, water ours, ours are these forests. Our forefathers raised them, its we who must protect them. -- Old Chipko Song (Garhwali language)[18]

Soon villagers, especially women, started organizing themselves under several smaller groups, taking up local causes with the authorities, and standing up against commercial logging operations that threatened their livelihoods. In October 1971, the Sangh workers held a demonstration in Gopeshwar to protest against the policies of the Forest Department. More rallies and marches were held in late 1972, but to little effect, until a decision to take direct action was taken. The first such occasion occurred when the Forest Department turned down the Sanghs annual request for ten ash trees for its farm tools workshop, and instead awarded a contract for 300 trees to Simon Company, a sporting goods manufacturer in distant Allahabad, to make tennis rackets. In March, 1973, the lumbermen arrived at Gopeshwar, and after a couple of weeks, they were confronted at village Mandal on April 24, 1973, where about hundred villagers and DGSS workers were beating drums and shouting slogans, thus forcing the contractors and their lumbermen to retreat. This was the first confrontation of the movement; the contract was eventually cancelled and awarded to the Sangh instead. By now, the issue had grown beyond the mere procurement of an annual quota of three ash trees, and encompassed a growing concern over commercial logging and the government's

forest policy, which the villagers saw as unfavourable towards them. The Sangh also decided to resort to tree-hugging, or Chipko, as a means of non-violent protest. But the struggle was far from over, as the same company was awarded more ash trees, in the Phata forest, 80 km away from Gopeshwar. Here again, due to local opposition, starting on June 20, 1973, the contractors retreated after a standoff that lasted a few days. Thereafter, the villagers of Phata and Tarsali formed a vigil group and watched over the trees till December, when they had another successful stand-off, when the activists reached the site in time. The lumberermen retreated leaving behind the five ash trees felled. The final flash point began a few months later, when the government announced an auction scheduled in January, 1974, for 2,500 trees near Reni village, overlooking the Alaknanda River. Bhatt set out for the villages in the Reni area, and incited the villagers, who decided to protest against the actions of the government by hugging the trees. Over the next few weeks, rallies and meetings continued in the Reni area. On March 26, 1974, the day the lumbermen were to cut the trees, the men of the Reni village and DGSS workers were in Chamoli, diverted by state government and contractors to a fictional compensation payment site, while back home labourers arrived by the truckload to start logging operations.[4] A local girl, on seeing them, rushed to inform Gaura Devi, the head of the village Mahila Mangal Dal, at Reni village (Laata was her ancestral home and Reni adopted home). Gaura Devi led 27 of the village women to the site and confronted the loggers. When all talking failed, and instead the loggers started to shout and abuse the women, threatening them with guns, the women resorted to hugging the trees to stop them

from being felled. This went on into late hours. The women kept an all-night vigil guarding their trees from the cutters till a few of them relented and left the village. The next day, when the men and leaders returned, the news of the movement spread to the neighbouring Laata and others villages including Henwalghati, and more people joined in. Eventually only after a four-day stand-off, the contractors left.

Aftermath

The news soon reached the state capital. Where then state Chief Minister, Hemwati Nandan Bahuguna, set up a committee to look into the matter, which eventually ruled in favour of the villagers. This became a turning point in the history of eco-development struggles in the region and around the world. The struggle soon spread across many parts of the region, and such spontaneous stand-offs between the local community and timber merchants occurred at several locations, with hill women demonstrating their new-found power as non-violent activists. As the movement gathered shape under its leaders, the name Chipko Movement was attached to their activities. According to Chipko historians, the term originally used by Bhatt was the word "angalwaltha" in the Garhwali language for "embrace", which later was adapted to the Hindi word, Chipko, which means to stick. Subsequently, over the next five years the movement spread too many districts in the region, and within a decade throughout the Uttarakhand Himalayas. Larger issues of ecological and economic exploitation of the region were raised. The villagers demanded that no forest-exploiting contracts should be given to outsiders and local communities should have effective control over natural

resources like land, water, and forests. They wanted the government to provide low-cost materials to small industries and ensure development of the region without disturbing the ecological balance. The movement took up economic issues of landless forest workers and asked for guarantees of minimum wage. Globally Chipko demonstrated how environment causes, up until then considered an activity of the rich, were a matter of life and death for the poor, who were all too often the first ones to be devastated by an environmental tragedy. Several scholarly studies were made in the aftermath of the movement. In 1977, in another area, women tied sacred threads, Raksha Bandhan, around trees earmarked for felling in a Hindu tradition which signifies a bond between brother and sisters. Womens participation in the Chipko agitation was a very novel aspect of the movement. The forest contractors of the region usually doubled up as suppliers of alcohol to men. Women held sustained agitations against the habit of alcoholism and broadened the agenda of the movement to cover other social issues. The movement achieved a victory when the government issued a ban on felling of trees in the Himalayan regions for fifteen years in 1980 by then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, until the green cover was fully restored. One of the prominent Chipko leaders, Gandhian Sunderlal Bahuguna, took a 5,000-kilometre trans-Himalaya foot march in 198183, spreading the Chipko message to a far greater area. Gradually, women set up cooperatives to guard local forests, and also organized fodder production at rates conducive to local environment. Next, they joined in land rotation schemes for fodder collection, helped replant degraded land, and established and ran nurseries stocked with species they selected.

Participants

Surviving participants of the first all-woman Chipko action at Reni village in 1974 on left jen wadas, reassembled thirty years later. One of Chipko's most salient features was the mass participation of female villagers. As the backbone of Uttarakhand's agrarian economy, women were most directly affected by environmental degradation and deforestation, and thus related to the issues most easily. How much this participation impacted or derived from the ideology of Chipko has been fiercely debated in academic circles. Despite this, both female and male activists did play pivotal roles in the movement including Gaura Devi, Sudesha Devi, Bachni Devi, Chandi Prasad Bhatt, Sundarlal Bahuguna, Govind Singh Rawat, Dhoom Singh Negi, Shamsher Singh Bisht and Ghanasyam Raturi, the Chipko poet, whose songs echo throughout the Himalayas. Out of which, Chandi Prasad Bhatt was awarded the Ramon Magsaysay Award in 1982, and Sundarlal Bahuguna was awarded the Padma Vibhushan in 2009.

The Chipko movement and women

The Chipko Movement in the Uttarakhand region of the Himalayas is often treated as a women's movement to protect the forest ecology of the Uttarakhand

from the axes of the contractors. But the reasons behind women's participation are more economic than ecological. In fact, the economic and ecological interests of Uttarakhand are so interwoven that it is difficult to promote one without promoting other. In this paper an attempt would be made to explain the reasons behind women's active participation in the Movement and their place within the Movement. The Chipko Movement began in 1971 as a movement by local people under the leadership of Dashauli Gram Swarajya Sangh (DGSS) to assert then rights over the forest produce. Initially demonstrations were organized in different parts of Uttarakhand demanding abolition of the contractual system of exploiting the forest-wealth, priority to the local forest-based industries in the dispersal o forestwealth and association of local voluntary organizations and local people in the management of the forests. In 1982 , in spite of these demonstrations, the DGSS (now DGSM, M for Mandal) was refused, by the Forest Department, on ecological grounds, the permission to cut 12 Ash trees to manufacture agricultural implements. At the same time, an Allahabad based firm was allotted 32 Ash trees from the same forest to manufacture sports goods. On hearing this news, Chandi Prasad Bhatt threatened to hug the trees to protect them from being felled rather than let them be taken away by this company. Till this time, however, the women were absent. In 1974, inspite of DGSS's protests, about 2500 trees of Reni forest were auctioned by the Forest Department. The DGSS planned to launch the Chipko Movement there. However, the local bureaucracy played the trick and managed to make the area devoid of local men as well as activists of the DGSS. To the utter surprise of everybody, 27 women of Reni village successfully prevented about 60

men from going to the forest to fell the marked trees. This was the first major success of the Chipko Movement. It is after this incident that attempts were made to project it as a women's movement. After this incident, the Reni Investigation Committee was set up by the U.P. Government and on its recommendations 1200 sq. km. Of river catchment area were banned from commercial exploitation. After Reni, in 1975, the women of Gopeshwar, in 1978, of Bhyudar Valley (threshold of Valley of Flower), of Dongary-Paitoli in 1980, took the lead in protecting their forests. In Dongari and Paitoli, the women opposed their men's decision to give a 60 acre Oak forest to construct a horticulture farm. They also demanded their right to be associated in the management of the forest. Their plea was that it is the woman who collects fuel, fodder, water, etc. The question of the forest is a life and death question for her. Hence, she should have a say in any decision about the forest. Now they are not only active in protecting the forests but are also in afforesting the bare hill-slopes.

Afforestation Programmes General Awakening

Since 1976, the IGSS started afforesting such which had become vulnerable to landslides. Initially this was also an all male programme. Sometimes local village women participated on some ornamental programme on the last day of the afforestation camp. However, the idea of increasing the association of women got momentum after 1978. In the beginning, the local women were assigned the responsibility of looking after the trees planted in their villages. While planting trees their suggestions were sought about the species to be planted. To solve the fodder problem, grass imported from Kashmir was planted. As the afforestation programme attempted to solve the problem of fuel and fodder, the women welcomed it. They looked after the trees so much so that the

survival rate is between 60-80 percent. In these afforestation camps, information about different aspects of local life is exchanged with the villagers. Their basic problems including the specific problems faced by women are discussed and ways of solving these problems are evolved. Because both the protection and afforestation programmes reflect the needs and aspirations of women, the women have spontaneously responded to the Chipko call and became the effective links of the movement. In fact recently, due to the awakening generated during the afforestation camps, women have started Mangal Dals in many villages have become very active. In our village, the women stood for elections for village head. Previously, the women used to be passive listeners in the camps too. In one of the recent camps, July-Aug 1982, women with breastfeeding children walked about 18 kilometers to participate in the afforestation camp there. The women, who till recently were mere limbs of the movement, have now risen to leadership roles.

Success of the Chipko Movement

Ban on cutting the trees for the 15 years in the forests of Uttar Pradesh in 1980. Later on the ban was imposed in Himachal Pardesh, Karnataka, Rajasthan, Bihar, Western Ghats and Vindhayas. More than 1,00,000 trees have been saved from excavation. It generated pressure for a natural resource policy which is more sensitive to people's needs and ecological requirements. Afterward environmental awareness increased dramatically in India. New methods of forest farming have been developed, both to conserve the forests and create employment.

By 1981, over a million trees had been planted through their efforts. Villagers paid special attention in care of the trees and forest trees are being used judiciously. The forest department has opened some nursery in villages and supplies free seedlings to the forest. This method often slowed the work and brought attention the governments actions. The Chipko is still working to protect the trees today through the same nonviolent methods. The chipko movement is teaching the people better land use ,nursery management and reforestation methods.

Conclusion:

As a diverse movement with diverse experiences, strategies, and motivations, Chipko inspired environmentalists both nationally and globally and contributed substantially to the emerging philosophies of eco-feminism and deep ecology and fields of community-based conservation and sustainable mountain development.

Reference: chipko movement - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chipko_movement The Chipko movement-

Chipko Movement, India : http://www.iisd.org/50comm/commdb/desc/d07.htm

The Chipko Movement (1987, India)- http://www.rightlivelihood.org/chipko.html The Chipko movement and women -- By Gopa Joshi - http://www.pucl.org/fromarchives/Gender/chipko.htm

http://edugreen.teri.res.in/explore/forestry/chipko.htm

You might also like

- Imaging Anatomy Brain and Spine Osborn 1 Ed 2020 PDFDocument3,130 pagesImaging Anatomy Brain and Spine Osborn 1 Ed 2020 PDFthe gaangster100% (1)

- Ambedkar Views PDFDocument87 pagesAmbedkar Views PDFShaifali gargNo ratings yet

- A Guide To Funeral Ceremonies and PrayersDocument26 pagesA Guide To Funeral Ceremonies and PrayersJohn DoeNo ratings yet

- Procedure Manual - IMS: Locomotive Workshop, Northern Railway, LucknowDocument8 pagesProcedure Manual - IMS: Locomotive Workshop, Northern Railway, LucknowMarjorie Dulay Dumol80% (5)

- Regionalism in India PDFDocument6 pagesRegionalism in India PDFKanakath Ajith100% (1)

- Environmental Movement in IndiaDocument7 pagesEnvironmental Movement in IndiaAnupam Bhengra75% (4)

- Partition of India HistoryDocument14 pagesPartition of India Historymeghna singhNo ratings yet

- TOPIC 2 - Fans, Blowers and Air CompressorDocument69 pagesTOPIC 2 - Fans, Blowers and Air CompressorCllyan ReyesNo ratings yet

- Socio Project Tribal Women in IndiaDocument22 pagesSocio Project Tribal Women in Indiashalviktiwari11100% (1)

- Eco FeminismDocument21 pagesEco FeminismLakshmi Annapoorna MuluguNo ratings yet

- Tribal DevelopmentDocument21 pagesTribal DevelopmentRakesh SahuNo ratings yet

- Chipko Movement History Project PDFDocument9 pagesChipko Movement History Project PDFsaif ali100% (2)

- The Chipko Movement or Chipko AndolanDocument8 pagesThe Chipko Movement or Chipko AndolanKingkhan LuvsyouNo ratings yet

- The Chipko Movement FinalDocument7 pagesThe Chipko Movement Finaltitiksha Kumar100% (1)

- Chipko MovementDocument22 pagesChipko Movementmirmax124100% (2)

- Chipko MovementDocument14 pagesChipko MovementKiran NegiNo ratings yet

- Chipko MovementDocument11 pagesChipko Movementh@rshiNo ratings yet

- Chipko MovementDocument15 pagesChipko MovementPranshu SinhaNo ratings yet

- Chipko Movement - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia PDFDocument8 pagesChipko Movement - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia PDFhikio300% (1)

- Group 8 Environmental Movements in IndiaDocument24 pagesGroup 8 Environmental Movements in IndiaV ANo ratings yet

- Chipko MovementDocument6 pagesChipko MovementcpsahNo ratings yet

- Environmental MovementsDocument46 pagesEnvironmental MovementsAkshat Bhadoriya100% (1)

- Chipko Movement: What Was It All About: Mr. Bahuguna Enlightened The Villagers by Conveying TheDocument10 pagesChipko Movement: What Was It All About: Mr. Bahuguna Enlightened The Villagers by Conveying TheAkshay Harekar100% (1)

- Environment Case StudiesDocument10 pagesEnvironment Case StudiesYuvraj AggarwalNo ratings yet

- Chipko MovementDocument10 pagesChipko Movementkarishma vermaNo ratings yet

- Chipko Movement....Document5 pagesChipko Movement....KUSHAL100% (1)

- Chipko MovementDocument9 pagesChipko MovementAviral Srivastava100% (2)

- AppikoDocument3 pagesAppikoSubash PrakashNo ratings yet

- The Gulabi GangDocument8 pagesThe Gulabi GangishitaNo ratings yet

- Chipo Movement AssignDocument4 pagesChipo Movement AssignhovoboNo ratings yet

- Dr. V. Srinivasa RaoDocument10 pagesDr. V. Srinivasa RaoDesh Vikas JournalNo ratings yet

- Appiko Movement HRCDocument13 pagesAppiko Movement HRCAnamika S100% (3)

- Implementation of Forest Rights Act 2006 in OdishaDocument7 pagesImplementation of Forest Rights Act 2006 in OdishaShay WaxenNo ratings yet

- Environmental Movements in IndiaDocument1 pageEnvironmental Movements in IndiaRahul RajwaniNo ratings yet

- Regionalism in IndiaDocument24 pagesRegionalism in IndiaAbhishekGargNo ratings yet

- Environmental Movement PDFDocument36 pagesEnvironmental Movement PDFYashika MehraNo ratings yet

- Superfoods and Bamboo For Tribal Livelihood & DevelopmentDocument3 pagesSuperfoods and Bamboo For Tribal Livelihood & DevelopmentUtkarsh GhateNo ratings yet

- Book Review and Summary - How Much Should A Person Consume by Ramachandra GuhaDocument60 pagesBook Review and Summary - How Much Should A Person Consume by Ramachandra GuhaNikhil NayyarNo ratings yet

- Agrarian Reform in IndiaDocument4 pagesAgrarian Reform in IndiaHarsh DixitNo ratings yet

- Environmental Movements in India: Some ReflectionsDocument11 pagesEnvironmental Movements in India: Some ReflectionsDrVarghese Plavila JohnNo ratings yet

- Tribal DevelopmentDocument6 pagesTribal DevelopmentDivyaNo ratings yet

- Analyzing The Livelihood Opportunities Among The Westernghats PDFDocument8 pagesAnalyzing The Livelihood Opportunities Among The Westernghats PDFRohit Kumar YadavNo ratings yet

- Advasi Developement PDFDocument12 pagesAdvasi Developement PDFdevika allaNo ratings yet

- Scheduled Tribes Education in India: Issues and ChallengesDocument10 pagesScheduled Tribes Education in India: Issues and ChallengesAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- BRLF 01 Profile PDFDocument20 pagesBRLF 01 Profile PDFc sridharNo ratings yet

- Women's MovementsDocument13 pagesWomen's MovementsGopinath Gujarathi100% (1)

- Assignment of Political Science 2Document6 pagesAssignment of Political Science 2kaiyoomkhanNo ratings yet

- Tribal Demography in IndiaDocument183 pagesTribal Demography in Indiavijaykumarmv100% (1)

- Environmental and Ecological MovementsDocument10 pagesEnvironmental and Ecological Movementskathayakku86% (7)

- Tribe and CasteDocument19 pagesTribe and CastekxalxoNo ratings yet

- Gandhiji'S Views On Basic Education and Its Present RelevanceDocument6 pagesGandhiji'S Views On Basic Education and Its Present RelevanceRaju mondalNo ratings yet

- Causes and Impact of Tebhaga MovementDocument2 pagesCauses and Impact of Tebhaga MovementRana SutradharNo ratings yet

- 03 Gandhi's Social Thought @nadalDocument159 pages03 Gandhi's Social Thought @nadalRamBabuMeenaNo ratings yet

- Model For Tribal Development: A Case Study of Jharkhand in Rural IndiaDocument30 pagesModel For Tribal Development: A Case Study of Jharkhand in Rural IndiaGobernabilidad DemocráticaNo ratings yet

- Wg11 WildlifeDocument122 pagesWg11 Wildlifejeyakar.mz8442No ratings yet

- Top 6 Peasant Movements in India - Explained! Emphasis On Tebhaga MovementDocument20 pagesTop 6 Peasant Movements in India - Explained! Emphasis On Tebhaga MovementRavi shankarNo ratings yet

- Jungle Bachao AndolanDocument8 pagesJungle Bachao AndolanR Raj kumar100% (3)

- UNit 6 PDFDocument13 pagesUNit 6 PDFAnkit SinghNo ratings yet

- Inclusive Growth and Gandhi's SwarajDocument18 pagesInclusive Growth and Gandhi's SwarajRubina PradhanNo ratings yet

- Sustainable - Livelihood - Enhacement-DJMV Final 22Document108 pagesSustainable - Livelihood - Enhacement-DJMV Final 22Swarup RanjanNo ratings yet

- Chipko MovementDocument10 pagesChipko Movementkunalkumar264No ratings yet

- Chipko Movement: Hindi Social-Ecological Gandhian SatyagrahaDocument6 pagesChipko Movement: Hindi Social-Ecological Gandhian SatyagrahaniranjanusmsNo ratings yet

- ENVIRONMENTAL MOVEMENTS IN INDIA FC ProjectDocument10 pagesENVIRONMENTAL MOVEMENTS IN INDIA FC Projectgayatri panjwaniNo ratings yet

- Chipko MovementDocument2 pagesChipko MovementArpit KapoorNo ratings yet

- New Microsoft Office Word DocumentDocument3 pagesNew Microsoft Office Word DocumentKC G Madhu100% (1)

- CorrelationsDocument3 pagesCorrelationsKC G MadhuNo ratings yet

- Use of E-Resources in Teaching and ResearchDocument31 pagesUse of E-Resources in Teaching and ResearchKC G MadhuNo ratings yet

- Presentation 1Document31 pagesPresentation 1KC G Madhu100% (1)

- Study 232Document14 pagesStudy 232KC G MadhuNo ratings yet

- Exchange 2010 UnderstandDocument493 pagesExchange 2010 UnderstandSeKoFieNo ratings yet

- System Administration ch01Document15 pagesSystem Administration ch01api-247871582No ratings yet

- An Enhanced RFID-Based Authentication Protocol Using PUF For Vehicular Cloud ComputingDocument18 pagesAn Enhanced RFID-Based Authentication Protocol Using PUF For Vehicular Cloud Computing0dayNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Cobit Framework - Week 3Document75 pagesIntroduction To Cobit Framework - Week 3Teddy HaryadiNo ratings yet

- Montessori Vs WaldorfDocument4 pagesMontessori Vs WaldorfAbarnaNo ratings yet

- Epson EcoTank ITS Printer L4150 DatasheetDocument2 pagesEpson EcoTank ITS Printer L4150 DatasheetWebAntics.com Online Shopping StoreNo ratings yet

- Article1414509990 MadukweDocument7 pagesArticle1414509990 MadukweemmypuspitasariNo ratings yet

- The Elder Scrolls V Skyrim - New Lands Mod TutorialDocument1,175 pagesThe Elder Scrolls V Skyrim - New Lands Mod TutorialJonx0rNo ratings yet

- Open Book Online: Syllabus & Pattern Class - XiDocument1 pageOpen Book Online: Syllabus & Pattern Class - XiaadityaNo ratings yet

- LADP HPDocument11 pagesLADP HPrupeshsoodNo ratings yet

- Business Mathematics (Matrix)Document3 pagesBusiness Mathematics (Matrix)MD HABIBNo ratings yet

- Zanussi Parts & Accessories - Search Results3 - 91189203300Document4 pagesZanussi Parts & Accessories - Search Results3 - 91189203300Melissa WilliamsNo ratings yet

- P&CDocument18 pagesP&Cmailrgn2176No ratings yet

- Thesis Statement On Lionel MessiDocument4 pagesThesis Statement On Lionel Messidwham6h1100% (2)

- Vishakha BroadbandDocument6 pagesVishakha Broadbandvishakha sonawaneNo ratings yet

- Section ADocument7 pagesSection AZeeshan HaiderNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Architecture Is The Architecture of The 21st Century. No Single Style Is DominantDocument2 pagesContemporary Architecture Is The Architecture of The 21st Century. No Single Style Is DominantShubham DuaNo ratings yet

- Topic - Temperature SensorDocument9 pagesTopic - Temperature SensorSaloni ChaudharyNo ratings yet

- Myth or Fact-Worksheet 1Document1 pageMyth or Fact-Worksheet 1Zahraa LotfyNo ratings yet

- Vehicles 6-Speed PowerShift Transmission DPS6 DescriptionDocument3 pagesVehicles 6-Speed PowerShift Transmission DPS6 DescriptionCarlos SerapioNo ratings yet

- Mod 2 MC - GSM, GPRSDocument61 pagesMod 2 MC - GSM, GPRSIrene JosephNo ratings yet

- MODULE 8. Ceiling WorksDocument2 pagesMODULE 8. Ceiling WorksAj MacalinaoNo ratings yet

- Bethelhem Alemayehu LTE Data ServiceDocument104 pagesBethelhem Alemayehu LTE Data Servicemola argawNo ratings yet

- Laminar Premixed Flames 6Document78 pagesLaminar Premixed Flames 6rcarpiooNo ratings yet

- Operaciones UnitariasDocument91 pagesOperaciones UnitariasAlejandro ReyesNo ratings yet

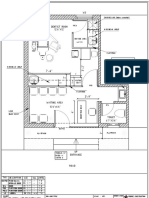

- Dental Clinic - Floor Plan R3-2Document1 pageDental Clinic - Floor Plan R3-2kanagarajodisha100% (1)